Tea Bowl with Crane Design - Asian Art Museum | Education

Tea Bowl with Crane Design - Asian Art Museum | Education

Tea Bowl with Crane Design - Asian Art Museum | Education

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

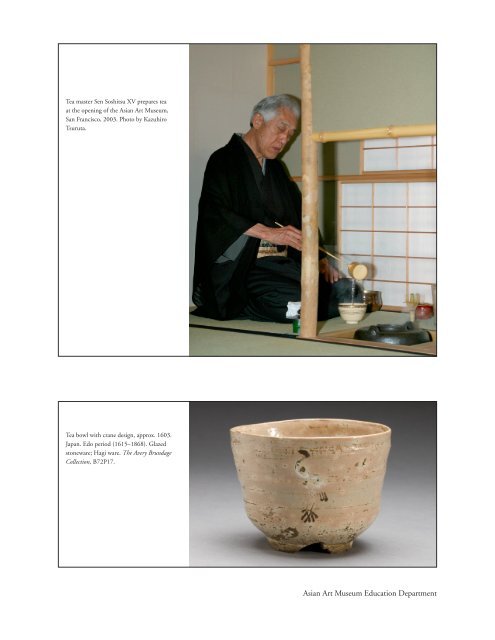

<strong>Tea</strong> master Sen Soshitsu XV prepares tea<br />

at the opening of the <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>,<br />

San Francisco, 2003. Photo by Kazuhiro<br />

Tsuruta.<br />

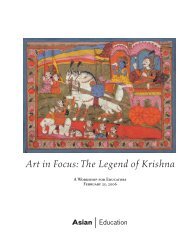

<strong>Tea</strong> bowl <strong>with</strong> crane design, approx. 1603.<br />

Japan. Edo period (1615–1868). Glazed<br />

stoneware; Hagi ware. The Avery Brundage<br />

Collection, B72P17.<br />

<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Department

Who is the man in the picture? What is he doing?<br />

Sen Soshitsu is the fifteenth generation head of the Urasenke<br />

tradition which provides instruction in the “Way of <strong>Tea</strong>”<br />

(Chado; also known as Chanoyu, literally “hot water for tea”).<br />

He has written that this practice, though often called the “tea<br />

ceremony, “ is not really a ceremony or ritual at all, but a way<br />

of life based on the simple act of serving tea <strong>with</strong> a pure heart.<br />

Beyond its spiritual aspect, the “Way of <strong>Tea</strong>” allows participants<br />

to interact <strong>with</strong> other people, <strong>with</strong> nature, and <strong>with</strong> the<br />

environment on a basic, satisfying level.<br />

The photograph shows Sen Soshitsu preparing tea at an<br />

event to mark the <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>’s re-opening in 2003.<br />

He is seated in a special tearoom installed in the museum’s<br />

Japanese art gallery, having just ladled hot water from an iron<br />

kettle that is heating on a brazier recessed into the floor. He<br />

<strong>Tea</strong> bowl (detail; B72P17).<br />

pours the hot water in a steady stream from a bamboo ladle<br />

into the tea bowl set before him on the mat. The utensils he<br />

uses and his carefully choreographed actions are both aspects<br />

of the practice that can be traced directly to the influential sixteenth century tea master Sen Rikyu<br />

(1522–1591). Sen Rikyu taught the way of tea to several samurai lords of his day.<br />

What is the object in the second picture? How was it used?<br />

The tea bowl is one of the most important utensils used in a tea gathering. A small quantity of powdered<br />

green tea is first removed from a tea container and placed into the bottom of the bowl. Water<br />

is added and the powdered tea and water are then blended together to form a bright green beverage,<br />

and the host presents the warm bowl of tea to his guest for drinking. After drinking the tea the guest<br />

carefully examines the tea bowl and the guest might comment on the bowl’s design, age, and beauty.<br />

For example, the crane decorating this bowl is an auspicious symbol associated <strong>with</strong> longevity and<br />

marital fidelity. Like most tea bowls, this one is made of clay, and has a soft, slightly pitted surface<br />

and ridged sides meant to rest comfortably in the drinker’s hands.<br />

What does this object tell us about the role of culture in samurai life?<br />

By the sixteenth century, the “Way of <strong>Tea</strong>” was wildly popular <strong>with</strong>in samurai society, as one of the<br />

cultural practices (bun) encouraged as a counterweight to military training (bu). Hideyoshi and<br />

Nobunaga, two of the great Momoyama era (1573–1615) warlords, were both ardent students of tea<br />

and collectors of tea bowls and other utensils. Nobunaga is even known to have awarded prized tea<br />

bowls to his vassals for meritorious duty in battle. It was their patronage of the tea master Sen Rikyu<br />

that led to his preeminence at the end of the sixteenth century.<br />

Rikyu favored simple, unadorned objects like this bowl as an expression of a kind of refined<br />

rusticity. Surprisingly, perhaps, the samurai valued this humble aesthetic even at a time when other<br />

art forms, such as painting, clothing, and even armor design showed a taste for flamboyant, bold,<br />

and colorful decoration made even more lavish <strong>with</strong> gold ornamentation.<br />

<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>Education</strong> Department