A Theory of Human Life History Evolution - Radical Anthropology ...

A Theory of Human Life History Evolution - Radical Anthropology ...

A Theory of Human Life History Evolution - Radical Anthropology ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ARTICLE <strong>Evolution</strong>ary <strong>Anthropology</strong> 179<br />

Hadza women produce more food<br />

than younger women do, postreproductive<br />

women produce less than<br />

Hadza men (Fig. 2). Furthermore, it is<br />

unlikely that the Hadza pattern <strong>of</strong><br />

high food production by postreproductive<br />

women is common among<br />

other foragers. Ache and Hiwi postreproductive<br />

women do not acquire<br />

even half the daily food energy acquired<br />

by adult men. !Kung data also<br />

suggest that older women produce<br />

very little, even leading the Hadza research<br />

team to ask “Why don’t elderly<br />

!Kung women work harder to feed<br />

their grandchildren?” (Blurton Jones<br />

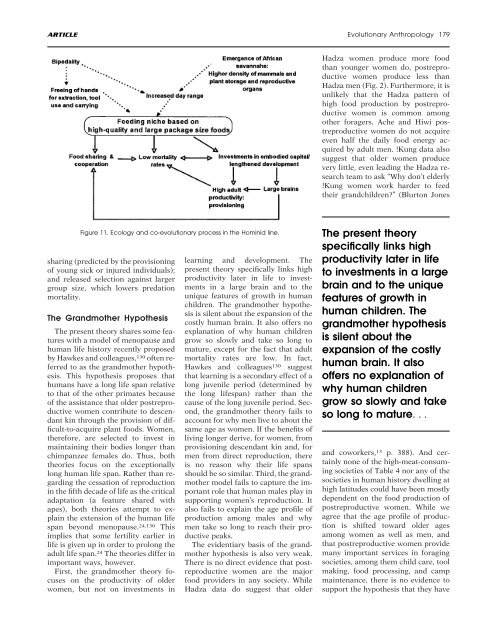

Figure 11. Ecology and co-evolutionary process in the Hominid line.<br />

sharing (predicted by the provisioning<br />

<strong>of</strong> young sick or injured individuals);<br />

and released selection against larger<br />

group size, which lowers predation<br />

mortality.<br />

The Grandmother Hypothesis<br />

The present theory shares some features<br />

with a model <strong>of</strong> menopause and<br />

human life history recently proposed<br />

by Hawkes and colleagues, 130 <strong>of</strong>ten referred<br />

to as the grandmother hypothesis.<br />

This hypothesis proposes that<br />

humans have a long life span relative<br />

to that <strong>of</strong> the other primates because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the assistance that older postreproductive<br />

women contribute to descendant<br />

kin through the provision <strong>of</strong> difficult-to-acquire<br />

plant foods. Women,<br />

therefore, are selected to invest in<br />

maintaining their bodies longer than<br />

chimpanzee females do. Thus, both<br />

theories focus on the exceptionally<br />

long human life span. Rather than regarding<br />

the cessation <strong>of</strong> reproduction<br />

in the fifth decade <strong>of</strong> life as the critical<br />

adaptation (a feature shared with<br />

apes), both theories attempt to explain<br />

the extension <strong>of</strong> the human life<br />

span beyond menopause. 24,130 This<br />

implies that some fertility earlier in<br />

life is given up in order to prolong the<br />

adult life span. 24 The theories differ in<br />

important ways, however.<br />

First, the grandmother theory focuses<br />

on the productivity <strong>of</strong> older<br />

women, but not on investments in<br />

learning and development. The<br />

present theory specifically links high<br />

productivity later in life to investments<br />

in a large brain and to the<br />

unique features <strong>of</strong> growth in human<br />

children. The grandmother hypothesis<br />

is silent about the expansion <strong>of</strong> the<br />

costly human brain. It also <strong>of</strong>fers no<br />

explanation <strong>of</strong> why human children<br />

grow so slowly and take so long to<br />

mature, except for the fact that adult<br />

mortality rates are low. In fact,<br />

Hawkes and colleagues 130 suggest<br />

that learning is a secondary effect <strong>of</strong> a<br />

long juvenile period (determined by<br />

the long lifespan) rather than the<br />

cause <strong>of</strong> the long juvenile period. Second,<br />

the grandmother theory fails to<br />

account for why men live to about the<br />

same age as women. If the benefits <strong>of</strong><br />

living longer derive, for women, from<br />

provisioning descendant kin and, for<br />

men from direct reproduction, there<br />

is no reason why their life spans<br />

should be so similar. Third, the grandmother<br />

model fails to capture the important<br />

role that human males play in<br />

supporting women’s reproduction. It<br />

also fails to explain the age pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong><br />

production among males and why<br />

men take so long to reach their productive<br />

peaks.<br />

The evidentiary basis <strong>of</strong> the grandmother<br />

hypothesis is also very weak.<br />

There is no direct evidence that postreproductive<br />

women are the major<br />

food providers in any society. While<br />

Hadza data do suggest that older<br />

The present theory<br />

specifically links high<br />

productivity later in life<br />

to investments in a large<br />

brain and to the unique<br />

features <strong>of</strong> growth in<br />

human children. The<br />

grandmother hypothesis<br />

is silent about the<br />

expansion <strong>of</strong> the costly<br />

human brain. It also<br />

<strong>of</strong>fers no explanation <strong>of</strong><br />

why human children<br />

grow so slowly and take<br />

so long to mature. ..<br />

and coworkers, 13 p. 388). And certainly<br />

none <strong>of</strong> the high-meat-consuming<br />

societies <strong>of</strong> Table 4 nor any <strong>of</strong> the<br />

societies in human history dwelling at<br />

high latitudes could have been mostly<br />

dependent on the food production <strong>of</strong><br />

postreproductive women. While we<br />

agree that the age pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> production<br />

is shifted toward older ages<br />

among women as well as men, and<br />

that postreproductive women provide<br />

many important services in foraging<br />

societies, among them child care, tool<br />

making, food processing, and camp<br />

maintenance, there is no evidence to<br />

support the hypothesis that they have