Water: a shared responsibility; 2006 - UN-Water

Water: a shared responsibility; 2006 - UN-Water

Water: a shared responsibility; 2006 - UN-Water

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

V A L U I N G A N D C H A R G I N G F O R W A T E R . 419<br />

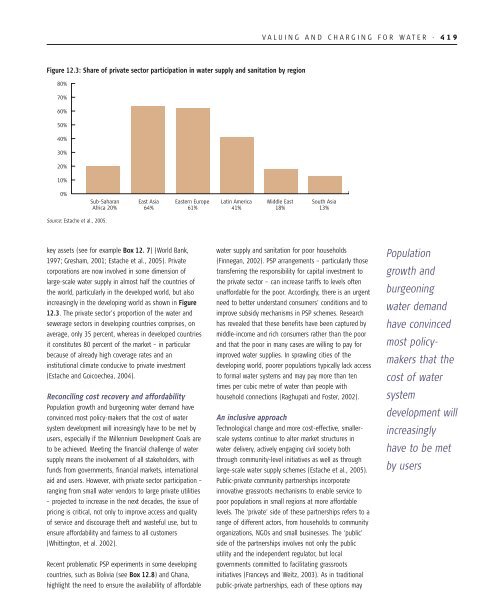

Figure 12.3: Share of private sector participation in water supply and sanitation by region<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

Sub-Saharan<br />

Africa 20%<br />

East Asia<br />

64%<br />

Eastern Europe<br />

61%<br />

Latin America<br />

41%<br />

Middle East<br />

18%<br />

South Asia<br />

13%<br />

Source: Estache et al., 2005.<br />

key assets (see for example Box 12. 7) (World Bank,<br />

1997; Gresham, 2001; Estache et al., 2005). Private<br />

corporations are now involved in some dimension of<br />

large-scale water supply in almost half the countries of<br />

the world, particularly in the developed world, but also<br />

increasingly in the developing world as shown in Figure<br />

12.3. The private sector’s proportion of the water and<br />

sewerage sectors in developing countries comprises, on<br />

average, only 35 percent, whereas in developed countries<br />

it constitutes 80 percent of the market – in particular<br />

because of already high coverage rates and an<br />

institutional climate conducive to private investment<br />

(Estache and Goicoechea, 2004).<br />

Reconciling cost recovery and affordability<br />

Population growth and burgeoning water demand have<br />

convinced most policy-makers that the cost of water<br />

system development will increasingly have to be met by<br />

users, especially if the Millennium Development Goals are<br />

to be achieved. Meeting the financial challenge of water<br />

supply means the involvement of all stakeholders, with<br />

funds from governments, financial markets, international<br />

aid and users. However, with private sector participation –<br />

ranging from small water vendors to large private utilities<br />

– projected to increase in the next decades, the issue of<br />

pricing is critical, not only to improve access and quality<br />

of service and discourage theft and wasteful use, but to<br />

ensure affordability and fairness to all customers<br />

(Whittington, et al. 2002).<br />

Recent problematic PSP experiments in some developing<br />

countries, such as Bolivia (see Box 12.8) and Ghana,<br />

highlight the need to ensure the availability of affordable<br />

water supply and sanitation for poor households<br />

(Finnegan, 2002). PSP arrangements – particularly those<br />

transferring the <strong>responsibility</strong> for capital investment to<br />

the private sector – can increase tariffs to levels often<br />

unaffordable for the poor. Accordingly, there is an urgent<br />

need to better understand consumers’ conditions and to<br />

improve subsidy mechanisms in PSP schemes. Research<br />

has revealed that these benefits have been captured by<br />

middle-income and rich consumers rather than the poor<br />

and that the poor in many cases are willing to pay for<br />

improved water supplies. In sprawling cities of the<br />

developing world, poorer populations typically lack access<br />

to formal water systems and may pay more than ten<br />

times per cubic metre of water than people with<br />

household connections (Raghupati and Foster, 2002).<br />

An inclusive approach<br />

Technological change and more cost-effective, smallerscale<br />

systems continue to alter market structures in<br />

water delivery, actively engaging civil society both<br />

through community-level initiatives as well as through<br />

large-scale water supply schemes (Estache et al., 2005).<br />

Public-private community partnerships incorporate<br />

innovative grassroots mechanisms to enable service to<br />

poor populations in small regions at more affordable<br />

levels. The ‘private’ side of these partnerships refers to a<br />

range of different actors, from households to community<br />

organizations, NGOs and small businesses. The ‘public’<br />

side of the partnerships involves not only the public<br />

utility and the independent regulator, but local<br />

governments committed to facilitating grassroots<br />

initiatives (Franceys and Weitz, 2003). As in traditional<br />

public-private partnerships, each of these options may<br />

Population<br />

growth and<br />

burgeoning<br />

water demand<br />

have convinced<br />

most policymakers<br />

that the<br />

cost of water<br />

system<br />

development will<br />

increasingly<br />

have to be met<br />

by users