pdf - Schwarz Gallery

pdf - Schwarz Gallery

pdf - Schwarz Gallery

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

SCHWARZ

AMERICAN PAINTINGS<br />

F I N E P A I N T I N G S SCHWARZ F O U N D E D 1 9 3 0<br />

P H I L A D E L P H I A<br />

1806 Chestnut Street Philadelphia PA 19103<br />

Tel 215 563 4887 Fax 215 561 5621 mail@schwarzgallery.com<br />

Art Dealers Association of America; Art and Antique Dealers League of America; CINOA

Philadelphia Collection LXXII<br />

Autumn 2003<br />

Copyright ©2003 The <strong>Schwarz</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

All rights reserved<br />

Library of Congress Control Number: 2003096059<br />

Editing: David Cassedy<br />

Copyediting: Alison Rooney, Kate Royer Schubert<br />

Design: Matthew North<br />

Photography: Rick Echelmeyer<br />

Color separations and printing: Piccari Press, Warminster, Pennsylvania<br />

Paintings are offered subject to prior sale.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

This is the first catalogue my son Robert has worked on from its beginnings since he joined the firm a little more than a<br />

year ago, and I would like to thank him for his participation in every stage of its development, especially the implementation<br />

of deadlines—an important consideration I sometimes lose sight of in my enthusiasm for other aspects of publishing a<br />

catalogue. I also thank David Cassedy, who has not only written many of the entries and organized the catalogue, but has<br />

also worked closely with the seven other scholars who have contributed essays. Their biographies appear at the end of the<br />

catalogue; I thank them here for the impressive quality of their research and writing.<br />

Matthew North is remarkable, not only for his handsome design of the catalogue, but also for the computer skills that went<br />

into nearly every aspect of its production. Christine Poole and Nathan Rutkowski are the <strong>Gallery</strong>’s newest employees and<br />

two of the most willing we have ever had. They have brought their enthusiasm to varied tasks, including physical<br />

examination of the paintings, coordination of photography, and ownership history research—important steps in a<br />

complicated project like this one. In addition to the gallery’s staff, I thank the following people for their assistance: Lou<br />

Barker, Jeffrey Boys, Jeffrey A. Cohen, Stiles Tuttle Colwill, Jacqueline M. De Groff, Elise Effnann, Mary Louise Fleisher,<br />

Kathleen A. Foster, Susan Glassman, Mary Anne Goley, Lance Humphries, Elizabeth Laurent, Cheryl Leibold, Audrey<br />

Lewis, Michael J. Lewis, Ellen Miles, Elle Shushan, Earle E. Spamer, and Mark Tucker.<br />

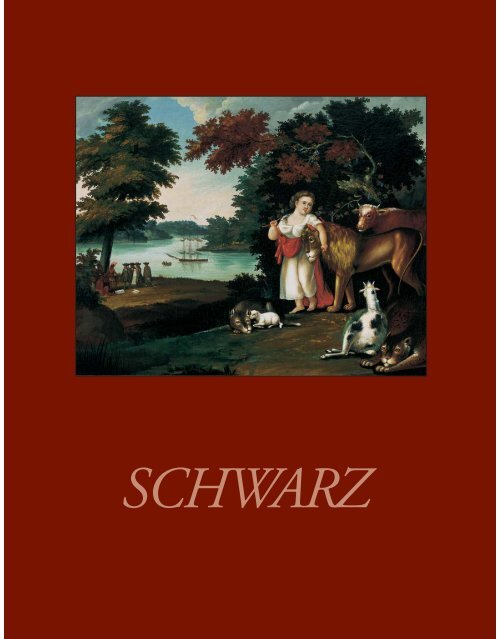

Edward Hicks’s Peaceable Kingdom (on the cover of the catalogue)—a rare example that remained in the artist’s family until<br />

now—is the subject of complementary essays by the two leading Hicks scholars, Carolyn Weekley and Scott Nolley. Works<br />

by members of the Peale family continue to be a speciality for which the <strong>Gallery</strong> is widely recognized, and this catalogue<br />

includes essays by two participants in the Peale Paintings Project at the Maryland Historical Society. Linda Simmons writes<br />

here on Charles Peale Polk’s portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Herman Henry Schroeder and James Peale’s View on the Wissahickon,<br />

which I believe to be the best of his dozen or so known landscapes from this period. Carol Soltis has contributed the most<br />

extensive discussion to date of the American career of Adolph-Ulric Wertmüller, the Swedish immigrant to Philadelphia,<br />

who was an associate of Rembrandt Peale, whose catalogue raisonné is an ongoing project for Dr. Soltis.<br />

Tony Lewis, the foremost expert on Thomas Birch, has written for us before; we are pleased to renew that relationship and<br />

to share his depth of knowledge of what may be the earliest known winter scene by the artist, who was one of the first<br />

Americans to explore a subject that quickly gained popularity with American collectors. Robert Torchia has completed many<br />

projects for us: most notably the monographs The Gilmans (1996), The Smiths: A Family of Philadelphia Artists (1999), and<br />

Xanthus Smith and the Civil War (1999); and essays for our landmark catalogue, 150 Years of Philadelphia Still Life Painting<br />

(1997). We are glad to publish his essays on Thomas Sully and Manuael Joachim de França in this cataogue.<br />

Milo Naeve’s discovery of and essay on John Lewis Krimmel’s The Disaster, a painting published here for the first time, is a<br />

real addition to our knowledge of early Philadelphia painting and the beginnings of American genre. Interestingly, my father<br />

purchased an exceptional Philadelphia armchair (c.1800–1810), many years ago from the same home where two paintings<br />

in this catalogue—the Krimmel and Charles Willson Peale’s portrait of Joseph Pilmore (as well as an important landscape<br />

by Thomas Birch)—were then hanging. We sold that chair to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the rest of the set is in<br />

the White House. The quality of that set of furniture is comparable to that of the famous Ephraim Haines furniture at<br />

Girard College (see my 1980 catalogue of the Stephen Girard Collection). The Krimmel painting offered here is an equally<br />

exciting example of the arts of Philadelphia in the early nineteenth century. New research uncovers more and more<br />

important early Philadelphia material for which connections—to one family or one house—can be documented, giving us<br />

a more comprehensive picture of Philadelphia’s culture. Sharing that evolving picture and offering fine paintings is our<br />

purpose in publishing these catalogues.<br />

—Robert D. <strong>Schwarz</strong>, Sr.

1<br />

Edward Hicks<br />

(American, 1780–1849)<br />

The Peaceable Kingdom, c. 1822–26<br />

Oil on canvas, 21 11 /16 x 27 inches<br />

Provenance: Hung in the artist’s home, Newtown, Pennsylvania; gift to his only<br />

son Isaac Worstall Hicks; his daughter Sarah Worstall Hicks; her grandniece<br />

Eleanore Hicks Lee Swartz; collection of a Hicks descendant<br />

Exhibited: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Williamsburg, Virginia,<br />

The Kingdoms of Edward Hicks (Feb. 7–Sept. 6, 1999); traveled to the Philadelphia<br />

Museum of Art (Oct. 10, 1999–Jan. 2, 2000), the Denver Art Museum (Feb. 12–Apr.<br />

30, 2000), the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum of the Fine Arts Museums of<br />

San Francisco (Sept. 24, 2000–Jan. 7, 2001)<br />

Recorded: Eleanore Price Mather and Dorothy Canning Miller, Edward Hicks:<br />

His Peaceable Kingdoms and Other Paintings (East Brunswick, N.J.: Associated<br />

University Presses, 1983), p. 116; Carolyn J. Weekley, The Kingdoms of Edward<br />

Hicks (Williamsburg, Va.: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, in association<br />

with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999), p. 191, no. 7 (repro. in color, p. 108, pl. 98)<br />

Reference: Scott W. Nolley and Carolyn J. Weekley, “The Nature of Edward<br />

Hicks’s Painting,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. 155, no. 2 (Feb. 1999), pp. 280–89<br />

(repro. in color, p. 286, pl. 9 and 9a)<br />

Edward Hicks, the Quaker minister and painter, was the son of Isaac and Catherine Hicks and the grandson of Gilbert Hicks<br />

of Bucks County, Pennsylvania. 1 The Hicks family was wealthy, owned considerable land, and operated several businesses in<br />

the area. Both Gilbert and Isaac held local posts associated with the colonial British government. In 1776, Gilbert was<br />

regarded as a traitor to American concerns and he fled Pennsylvania. Hicks’s family lands were then confiscated and the<br />

artist’s parents lived in reduced circumstances thereafter.<br />

Hicks’s mother died when he was almost two years old. Unable to care for all of his five young children, his father boarded<br />

most of them with Bucks County families. In 1785, Hicks went to live with the Quakers David and Elizabeth Twining on<br />

their farm near Newtown. Ten years later, the youngest Hicks child was apprenticed to the coach makers William and Henry<br />

Tomlinson in nearby Langhorne. It was during his five-year apprenticeship that Edward learned a variety of techniques<br />

associated with ornamental painting, an important branch of the coach and carriage making business.<br />

Edward was not a birthright Quaker, nor was he a Friend when he served his apprenticeship and learned his trade. His immediate<br />

family was Anglican. After the death of his mother, his father sometimes attended the Newtown Presbyterian Church. Neither<br />

of these religious affiliations would have discouraged Hicks’s pursuit of painting as a career, including his eventual easel pictures<br />

of local farms, historical subjects, and pastoral scenes. Some conservative Quakers, including those living in rural Bucks County,<br />

considered such artwork to be frivolous, of no use, and contrary to Quaker codes of plainness and simplicity.<br />

By 1803, however, Hicks had become deeply interested in the Society of Friends, had married Sarah Worstall, a member of<br />

Middletown Monthly Meeting, and had been received into membership at the same meeting. His increasing work for the<br />

Friends became the most important aspect of his life. In 1811, Middletown Monthly Meeting recorded Hicks as a Quaker<br />

minister. Ultimately it was the profound influence of his religious life and his response to criticism that led him to create<br />

the Peaceable Kingdom pictures for which he is so widely known today. Decorative painting of the type he performed in his

shop, especially some of the elaborate signboards, quickly came under the scrutiny of local conservative Quakers. Such work<br />

was considered questionable in its highly decorative aspects and often discouraged by Quakers, but it was considered<br />

particularly inappropriate for a Quaker minister to produce such items. Hicks recognized this conflict but realized that<br />

ornamental painting, the only trade that he knew, made it possible to support his family and the costs of his extended,<br />

traveling ministry. His creation of the first Peaceable Kingdom pictures in about 1816–18 may have been his contrived effort<br />

to allay criticism and provide an image that was consistent with Quaker beliefs.<br />

The earliest of the Kingdom pictures were likely less refined and organized than the more sophisticated versions that<br />

followed. Only one example dating before 1820 is known: an oil on canvas picture owned by the Cleveland Museum of Art.<br />

About 1822, or perhaps a year or so before, Hicks began to develop the well-known “border” Kingdoms. These versions,<br />

with the exception of one, have lettered (and sometimes rhyming) verses in borders surrounding the Kingdom view. The<br />

lettered messages convey the Biblical prophecy of Isaiah that inspired the pictures. Several of the border Kingdoms survive,<br />

and none are identical. The example illustrated here is especially interesting because of its history of descent in the Hicks<br />

family. It originally hung in Hicks’s house in Newtown and he eventually gave it to his only son, Isaac Worstall Hicks.<br />

The borders of the picture also survive and were likely removed by an unidentified member of the family. Conservation<br />

treatment of the picture in 1998 revealed new and important information about Hicks’s techniques and materials, as related<br />

by Scott Nolley in his accompanying article. For the art historian some of the most interesting aspects include the artist’s<br />

tendency to overlap elements within the composition, a layering process that is not often observed in pictures by studiotrained<br />

painters. The kid or goat was altered in an effort to improve the foreshortening of the left side of the animal as it<br />

recedes into space. Such corrective passages, also seen in Hicks’s other pictures, document his continuous attempts to<br />

improve his work. Some aspects of his paintings are often built up in a series of glazes or a number of layers of paint. Drop<br />

shadows usually comprised of dark-colored expanses of paint with clearly defined edges were used here to help define the<br />

positions of elements in space. The dark areas below the kid’s hooves and rump and below the large leopard’s paws at lower<br />

right are classic examples of drop shadows used by Hicks. Such techniques are commonly associated with signboard<br />

painting, one aspect of his shop work. The Hicks family Kingdom is also a good example of his occasional attempt to imitate<br />

more academic methods for rendering fabrics and other materials, as seen in the diaphanous quality of the child’s dress.<br />

The composition of this particular Kingdom scene is similar to several others from the same period. A limited number of<br />

animals, one child, and the small distant view of the Penn’s Treaty group in the middle ground at left beside the river typify<br />

the general arrangement of these paintings. Many of the elements were borrowed from known print sources, a practice that<br />

Hicks used during much of his career. The inclusion of a blasted tree trunk with one or more branches of dying brown leaves<br />

is a known artistic convention for the period, but Hicks seems to have shaped and painted it many different ways to suit his<br />

particular vision for each picture.<br />

Hicks would eventually develop other formats for the Kingdoms as he aged and as he used them to convey particular<br />

meanings about the welfare of the American Society of Friends. He never tired of altering the scene and of combining and<br />

recombining animals in various ways to illustrate certain ideas. At the time of his death in 1849 he was working on a Peaceable<br />

Kingdom picture for his daughter. One account indicates that Hicks was working on the picture the day before he died.<br />

Note<br />

—Carolyn J. Weekley<br />

1. Information in this entry was taken from Carolyn J. Weekley, The Kingdoms of Edward Hicks (Williamsburg, Va.: The Colonial Williamsburg<br />

Foundation, in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999).

The Creation of a Peaceable Kingdom<br />

Of the Peaceable Kingdom paintings by Hicks, the pictures that comprise the border Kingdom series are clearly those in<br />

which Hicks was teaching himself how to paint easel works. As a sign painter he would have learned how to combine visual<br />

elements and utilize the techniques of tracing and transfer of image material to compose an integrated image that would<br />

convey a single idea. Using these familiar techniques Hicks composed his Kingdom tableaux using images from selected print<br />

sources and sketches taken from life. Examination of a number of these early border Kingdom works using x-radiography and<br />

infrared reflectography illustrated just how much Hicks relied on these techniques to assemble his imagery. Extensive<br />

underdrawing can be seen of not only the animals and figures but also landscape and foreground elements. A number of these<br />

formative paintings, when radiographed, indicate that Hicks painted the surrounding landscapes intuitively. A complete sky,<br />

then the mountainous landscape, and the middle ground and foreground imagery would have been meticulously executed,<br />

layer upon layer, to create the overall landscape perspective. Additional underdrawing, appearing as detailed and completed<br />

sketches, becomes visible beneath selected animals. In many cases these animals have been directly associated with<br />

contemporary print sources and, as one might expect, often appear in reverse orientation from the print source image, an<br />

artifact of the tracing and transfer processes he used. With this in mind, one can often see these “lifted” images as animals<br />

that seem to float, curiously, amidst the more practiced aspects of his composition.<br />

It is interesting to note that Hicks, a devoted and charismatic Quaker minister, often referred to his love of easel painting<br />

as an indulgent character flaw. That he was capable of a more academic style of painting and rarely pursued it until the end<br />

of his life might largely be attributed to the constraints of the Quaker religion to which he was quite devoted, a religion that<br />

largely eschewed decorative painting and ornamentation for favor of plainness and simplicity of dress. It is not an<br />

uncommon assertion that the inclusion of a Biblical text or proverb as a text border was yet another way of avoiding similar<br />

criticism while also combining his love of painting with his ministry.<br />

As Hicks gained confidence with his subject, his unique style emerged. The text borders disappeared and in time gave way<br />

to larger image areas. The effort to execute realistic, atmospheric perspective seems to relax, giving way to a flatter picture<br />

plane. The landscape begins to tilt toward the viewer and the animals and figures appear as if cut from paper, arranged one<br />

atop another throughout the landscape. It is here that we become aware of a certain resurgence of his training and<br />

background as a sign painter where softer, sculptural three-dimensional modeling gives way to bold, calligraphic brushwork<br />

and a certain “posterization” of form. Another example of the return to sign painting technique can be seen in the use of<br />

drop shadowing. These broad-stroke, characteristic shadows that surround and give emphasis to lettering come to use in the<br />

outline and shadowing of animals and figures.<br />

This painting stands as an extraordinary example in Hicks’s evolution of the Peaceable Kingdom from both an aesthetic and<br />

academic point of view. It is actually an example of a late border Kingdom. The text border has been removed and the work<br />

installed on a new support in its present dimension, apparently during the artist’s lifetime. That the text border remains<br />

extant, reading: “A little child was leading them in love,/And not one savage beast was seen to frown,/His grim carniv’rous<br />

nature there did cease,/When the great PENN his famous treaty made,” resonates as metaphor for the pivotal place this work<br />

occupies in the genre. The image has been achieved with a meticulously executed cloud-filled sky, largely obscured by foliage<br />

and landscape as in the early Kingdom works. Now, though, the picture plane begins to tilt toward the viewer. Strong though<br />

somewhat tentative drop shadows begin to appear, defining figures, and the animals themselves appear flatter and more<br />

graphic, in composition. The atmosphere of the sky is treated less academically, with billowing clouds giving way to the<br />

characteristic blue-to-pink sky that is often associated with the later Kingdom pictures, now appearing on the horizon. His

increasing comfort with his subject is best illustrated by a markedly diminished use of underdrawing. The small, kneeling<br />

lamb in the foreground—a direct lift from the Robert Westall engraving The Peaceable Kingdom of the Branch that inspired<br />

the image—is the only figure in the painting executed first in Hicks’s usual fastidious underdrawing.<br />

The binder-rich paints that would characterize the durable media used by a sign painter are all in evidence here. The remarkable<br />

condition of the paint surface can largely be attributed to Hicks’s knowledge of paint formulation, as well as the painting’s<br />

escape from inexpert and overzealous restoration. Brushwork is confident and spontaneous, and his attention to minute detail,<br />

not always surviving in many of his other works, can be seen here in, for example, the fringe of the figure’s dress, rendered by<br />

drawing a point through the wet paint, or the meticulously layered glazes depicting the lion’s mane or water’s surface.<br />

This is not a rote work for Hicks, however. A number of the artist’s changes are visible through subsequent paint layers,<br />

particularly his struggle with rendering the figure of the goat. Challenged by the indirect, foreshortened perspective of this<br />

particular figure, he made several attempts to perfect the contour of the form. Hicks also continued to experiment with new<br />

pigments and colors. The foreground applications of a very granular, cool, emerald-green verdigris paint appear outside his<br />

otherwise consistent use of a fluid, almost inky paint medium. It would have been a pigment largely unsuitable for use in<br />

signs and other work intended for exposure to the elements, but was attractive enough to Hicks, despite its less-than-ideal<br />

consistency, to continue its use in his easel painting throughout his career. The unbound, sugary surface of this particular<br />

paint color appears in larger, later works, such as his landscapes depicting the Cornell and Leedom farms.<br />

When the traveling exhibition of Hicks’s paintings The Kingdoms of Edward Hicks was initially installed in the galleries of<br />

Colonial Williamsburg’s Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum (then the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center),<br />

Hicks’s self-taught progression as an easel painter became clear. The unprecedented opportunity to view, side-by-side, works<br />

that illustrate this Biblical subject allowed a broad view of how the artist used his training as a sign and carriage painter to<br />

gain aptitude in fine-art painting techniques. The pivotal work shown here, a Peaceable Kingdom that has been in the Hicks<br />

family since it was painted, remains in splendid condition and as one of the best examples of his evolving technique.<br />

—Scott W. Nolley

2<br />

Du Vivier<br />

(French, active United States 1796–1807/1808)<br />

A Mid-Atlantic Town House, c. 1796–1808<br />

Oil on canvas, 27 1 /4 x 37 inches<br />

Signed at lower right: “Du Vivier fecit”<br />

According to George C. Groce and David H. Wallace in The New-York Historical Society’s Dictionary of Artists in America,<br />

1564–1860, Duvivier and Son taught drawing in Philadelphia, 1796–97. 1 The authors go on to state that the elder artist<br />

claimed that he had been a member of the Royal Academy in Paris and that at least one of the two artists was still in<br />

Philadelphia in 1798. 2<br />

Listings for artists named Du Vivier have not been found in Philadelphia directories. Lewis (probably Louis) Duvivier,<br />

M.D., is listed in 1800 at 381 South Front Street; the name may be merely a coincidence. The Historical Society of<br />

Pennsylvania has a manuscript accession record (1886) for a miniature of a Dr. Duvivier, painted in Paris circa 1795,<br />

according to the donor. 3 The donor (or her agent) also related her belief that Dr. Duvivier had assisted Stephen Girard in<br />

aiding yellow fever victims in Philadelphia. The poplars in this painting are reminiscent of the ones in the 1807 depiction<br />

by John James Barralet (1747–1815) of the John Dunlap house (watercolor and gouache on canvas, 17 1 /2 x 26 1 /2 inches;<br />

Girard College, Philadelphia) at Twelfth and Market streets, built in 1789, leased to the French legation in the 1790s, and<br />

sold to Stephen Girard in 1807. 4 A suggested link between the Du Viviers and the artist and museum proprietor Pierre<br />

Eugène Du Simitière (c. 1736–1784) is almost certainly a red herring, probably the result of someone misreading the name<br />

Du Vivier: Du Simitière died before the Du Viviers are known to have been in Philadelphia.<br />

Alfred Coxe Prime transcribed three Philadelphia newspaper advertisements placed by the Du Viviers. The earliest appeared<br />

in the Aurora on May 25, 1796, and gave their address as 112 Race Street. 5 A more informative advertisement appeared in<br />

the Pennsylvania Packet on May 23, 1797:<br />

Academy of Drawing and Painting. Duvivier and Son, having moved their academy from North Second<br />

street, to No. 12 Strawberry street [between Second and Third streets, near Market], where they continue<br />

teaching drawing, which they execute in the presence of their pupils, and consequently excludes prints or<br />

any foreign aid and the advantages arising from this mode, must be self evident to any reflecting mind.<br />

Ladies are taught Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, from eleven until 1 o’clock in the morning [sic], and<br />

ladies and gentlemen on the afternoon of each day (Saturday excepted) from 3 to 5 o’clock. They have<br />

provided themselves with separate airy apartments, where each sex are attended separate. Mr. Duvivier being<br />

possessed of a secret and curious mode of painting on silk, satins, &c, the colours of which will never fade,<br />

either by time or repeated washings, but will continue its brilliancy and beauty, which renders it very<br />

desirable for tire [sic] screens, chair bottoms, curtains, trimmings, &c. They also furnish a variety of patterns<br />

for young ladies working the above, and which may be executed with as much elegance and considerable less<br />

trouble and expense [sic] than embroidery. Also a new invented and beautiful tapestry, composed by Mr.<br />

Duvivier, which from its variety, beauty and cheapness, is perhaps superior to any ever offered the American<br />

Public. They would occasionally give lessons in private families. Specimens of their abilities, consisting of<br />

views, landscapes, sea ports, historical pieces, fruit, &c are to be seen and sold at their academy. 6<br />

Another advertisement in the Pennsylvania Packet on October 31, 1797, added that evening hours, from 7 to 9 o’clock,<br />

could be arranged, and that the Du Viviers’ instruction was available “at reasonable terms of two dollars per month.” 7

The Smithsonian American Art Museum Inventory of American Paintings lists two undated watercolor portraits by Duvivier<br />

and Son: 8 a 1787 pastel portrait ascribed to Duvivier and/or Du Simitière; and a circa 1800 watercolor portrait, the<br />

signature on which has been transcribed as J. F. Duvuvier. 9<br />

Could this painting be one of the “specimens of the [Du Viviers’] abilities, consisting of views [and] landscapes” that they<br />

displayed in their academy? The picturesque landscape and genre elements at the right demonstrate their abilities in this<br />

type of decorative painting, but this painting was probably intended to be a house portrait. The architectural historian<br />

Jeffrey A. Cohen has observed that “the back buildings of the five-bay, center-hall house seem carefully observed, so this may<br />

well be true to the place rather than some generic view.” 10 Although there is considerable evidence suggesting that this<br />

painting is a Philadelphia view, Cohen has also noted that “from the visual evidence only, it could easily have been some<br />

other mid-Atlantic city or even a town, which might explain the unusual lack of a second side of the street, the extraordinary<br />

width of the road, and the seemingly ungridded intersection at the right.” 11 In fact, it is now known that in 1798, the Du<br />

Viviers moved to Baltimore, where they advertised their services in the Federal Gazette on November 21, under the heading<br />

of “Drawing Academy. F. DUVIVIER & SON From Philadelphia, . . . at No. 36 North Gay-street.” 12 They opened a<br />

museum August 13, 1799, and are thought to have been in Baltimore as late as 1808. 13<br />

Could this painting have been commissioned by the owner of the five-bay brick house? If the artist painted this view on<br />

speculation, why did he choose to feature this house? The wealth or notoriety of the house’s owner or occupants could have<br />

made the painting attractive to prospective buyers. Cohen estimates that “there may have been a few dozen brick, five-bay,<br />

center-hall houses like this one in 1790s Philadelphia” 14 and suggests a construction date between the 1750s and 1770s. 15<br />

Cohen also states that “judging just by population, Baltimore may have had nearly half as many, and there may have been<br />

one or two in each of several other towns in the region.” 16<br />

A personal association may have prompted Du Vivier to feature this particular house, one that he saw every day, or perhaps<br />

the house where he lived or had his school. If he painted the house for such personal reasons, investigation of his known<br />

Philadelphia and Baltimore addresses may eventually lead to the house’s identification.<br />

Notes<br />

1. George C. Groce and David H. Wallace, The New-York Historical Society’s Dictionary of Artists in America, 1564–1860 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale<br />

University Press, 1957), p. 200. 2. Groce and Wallace, Dictionary of Artists in America, p. 200. E. Bénézit, Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des<br />

pientres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs (Paris: Librairie Grund, 1976), vol. 4, pp. 77–78, lists twenty-seven French and Belgian artists named<br />

Duvivier. Travel in the United States is not mentioned for any of them. 3. Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Society Misc. Coll.,<br />

Annie L. Litch. 4. See Robert D. <strong>Schwarz</strong>, The Stephen Girard Collection: A Selective Catalogue (Philadelphia: Girard College, 1980), no. 1. Du<br />

Vivier’s name does not appear in the name index to the Stephen Girard papers at Girard College. 5. Alfred Coxe Prime, The Arts and Crafts in<br />

Philadelphia, Maryland, and South Carolina (1786–1800), series 2, Gleanings from Newspapers (New York: The Walpole Society, 1933), p. 47.<br />

6. Prime, The Arts and Crafts in Philadelphia, p. 47. 7. Ibid., p. 48. 8. The inclusion of these portraits in the exhibition catalogue Virginia Miniatures<br />

(Richmond: Virginia Museum, 1941) suggests that the Du Viviers may have worked in Virginia. 9. Repro. in Stiles Tuttle Colwill, “A Chronicle of<br />

Artists in Joshua Johnson’s Baltimore,” in Joshua Johnson: Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter by Carolyn J. Weekley et al. (Baltimore:<br />

Maryland Historical Society, 1987), as fig. 12. Unknown Woman by J. F. Duvivier, c. 1800, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore. The Du Vivier’s<br />

advertisement in the Nov. 21, 1798, Federal Gazette mentions “profile and other likenesses, at all prices.” See n. 12 below. 10. Jeffrey A. Cohen,<br />

letter to David Cassedy, April 18, 2003. 11. Jeffrey A. Cohen, letter to David Cassedy, May 27, 2003. 12. Federal Gazette, Nov. 21, 1798, p. 2,<br />

col. 3, repro. in Colwill, “A Chronicle,” p. 79, n. 25. 13. Colwill, “A Chronicle,” p. 79. The elder Du Vivier is identified here as J. F. Duvivier.<br />

14. Cohen, letter, April 18, 2003. On May 27, Cohen added: “A five-bay house would be unlikely to be less than 25-foot frontage. Only 10 of the<br />

186 properties surveyed for [the High Street] ward had frontage of 25 feet or more. This is probably one of the wealthier of the half-dozen or so city<br />

wards, the boundaries of which are given in the old printed city ‘Ward Genealogy.’” Cohen cited the online database of the High Street Ward from<br />

the 1798 U.S. direct tax, compiled by Bernard Herman of the University of Delaware’s Center for Historic Architecture and Design and posted (for<br />

opening using Microsoft Excel) at http://www.math.udel.edu/~rstevens/datasets.html. 15. Cohen, letter, April 18, 2003. 16. Jeffrey A. Cohen,<br />

letter to David Cassedy, July 7, 2003.

3<br />

Charles Willson Peale<br />

(American, 1741–1827)<br />

The Reverend Joseph Pilmore (1739–1825), 1787<br />

Oil on canvas, 23 x 18 3 /4 inches<br />

Provenance: Joseph Pilmore; his second wife (who was the widow of Bishop<br />

William White); the Poulson family (relatives of the Whites); Mrs. Susan Poulson;<br />

Dr. Wilson Poulson, Linwood (on the Delaware River near Chester, Pennsylvania);<br />

Gurney Poulson Sloan, Dunedin, Florida; <strong>Schwarz</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> by 1987; Pennsylvania<br />

private collection until 2003<br />

Exhibited: Kennedy Galleries, New York, American Masters, 18th and 19th<br />

Centuries (Mar. 14–Apr. 7, 1973), repro. in cat., pl. 5<br />

References: Charles Coleman Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale with Patron and<br />

Populace: A Supplement to Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson Peale,” in<br />

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 59, pt. 3 (Philadelphia:<br />

American Philosophical Society, May 1969), p. 76 (repro. p. 126); Charles Coleman<br />

Sellers, “Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson Peale,” in Transactions of the<br />

American Philosophical Society, vol. 42, pt. 1 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical<br />

Society, 1952), no. 169 (as unlocated); Robert Devlin <strong>Schwarz</strong>, A <strong>Gallery</strong> Collects<br />

Peales, Philadelphia Collection XXXV (Philadelphia: <strong>Schwarz</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, 1987), no. 7<br />

(repro. in color); Wendy J. Shadwell, “The Portrait Prints of Charles Willson Peale,”<br />

in Eighteenth-Century Prints in Colonial America, ed. Joan D. Dolmetsch<br />

(Williamsburg, Va.: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1979), pp. 134–40<br />

Charles Willson Peale has been the subject of numerous books, articles, and exhibitions. His life and his multiple careers as<br />

a painter, a patriot, a museum founder, an inventor, a farmer, and a naturalist have been detailed by many scholars including<br />

Charles Coleman Sellers, Edgar P. Richardson, Brooke Hindle, and Lillian B. Miller.<br />

Charles Willson Peale was born in Maryland in 1741 and apprenticed to a saddler by 1754. After his release from this<br />

apprenticeship, he set up a shop in Annapolis. In 1762 he married Rachel Brewer, the first of his three wives. At about this time<br />

he developed an interest in painting and studied for a short time with John Hesselius in Maryland and then in Boston with<br />

John Singleton Copley (1738–1815). In 1766, eleven prominent Marylanders subscribed to a fund that permitted Peale to<br />

study with Benjamin West in London, where he remained for a little less than three years. He returned to Maryland in 1769<br />

and painted there, in Philadelphia, and in Virginia. He first painted George Washington in 1772.<br />

In 1776 Peale settled in Philadelphia, where he became active in politics and enrolled in the city militia. During the<br />

Revolutionary War he served in the Continental Army, seeing action at Princeton and arduous winter encampment at Valley<br />

Forge. After the war he continued to paint portraits of Washington and other heroes of the Revolution. By 1782 he had<br />

opened a portrait gallery in his Philadelphia studio, and by 1786 he had founded his Philadelphia Museum for the display

of natural history specimens, the first such museum in the United States. In 1790, Rachel Peale died, and the following year<br />

Charles Willson married Elizabeth De Peyster. In 1794 Peale moved his museum to Philosophical Hall and participated in<br />

the founding of the short-lived Columbianum or American Academy of the Fine Arts. The management of his museum<br />

became his principal occupation, and although Peale publicly announced his retirement from painting, he still found time<br />

to paint such major works as The Exhumation of the Mastodon (Peale Museum, Baltimore), to experiment with such<br />

inventions as the polygraph, to mount the first paleontological dig in the United States, and to give artistic training to his<br />

children and his nieces and nephews, many of whom became artists. His second wife died in 1804 and the next year he<br />

married Hannah Moore.<br />

Peale “retired” from his museum in 1810, gave it over to his son Rubens to manage, and moved to Belfield Farm near<br />

Philadelphia. The farm occupied his interest until after the death of his wife Hannah in 1821. He then returned to<br />

Philadelphia and resumed the management of his museum. In 1818 he resumed painting portraits and continued until his<br />

death in 1827 at the age of eighty-six. Peale was buried at St. Peter’s churchyard in Philadelphia. In Charles Willson Peale<br />

and His World, Edgar Richardson succinctly appraised the man: “He was an artist of a strong, simple, severe neoclassic style;<br />

a pioneer in American natural history and in the development of the public museum; and a man of great skill, ingenuity,<br />

and benevolence.” 1<br />

Joseph Pilmore was born in Yorkshire, England, and attended John Wesley’s school at Kingswood. An early convert to<br />

Methodism, he came to Philadelphia in 1769 as a lay preacher. Pilmore subsequently broke with Wesley over the latter’s policy<br />

regarding ordination of ministers. Edgar P. Richardson wrote that after the Revolution ended, Pilmore returned to England,<br />

where he was ordained as a minister in the Anglican Church. 2 He then returned to Philadelphia, where he became a popular<br />

preacher. Saint Paul’s Church on Third Street, which was said to have the largest interior in the former colonies, was built to<br />

accommodate the crowds attracted by Pilmore’s eloquent preaching. 3 In addition to preaching at Saint Paul’s, he was rector of<br />

the united parishes of Trinity (Oxford), All Saints (Lower Dublin), and Saint Thomas’s (Whitemarsh), in Montgomery County.<br />

In 1772 Charles Willson Peale painted a portrait of Mary Benezet, daughter of Daniel and Elizabeth North Benezet, who<br />

married the Reverend Joseph Pilmore in 1790. Her portrait is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. After her death<br />

Pilmore married the widow of William White, the first Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States. Since the<br />

Pilmores had no children, their portraits descended in the White and Poulson families.<br />

This portrait of Joseph Pilmore, which was later engraved by the artist (see plate 4), may be compared to a similar and welldocumented<br />

portrait of George Washington that Peale also engraved (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia).<br />

It is known that Washington sat for that portrait in 1787, so the same date is plausible for this painting. Both paintings are<br />

clearly related to their mezzotints published that year, although Pilmore’s portrait has a rectangular format. The Washington<br />

portrait remained with the artist as part of his museum collection, while the Pilmore portrait went directly to the sitter.<br />

Notes<br />

1. Brooke Hindle, Lillian B. Miller, and Edgar P. Richardson, Charles Willson Peale and His World (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1973), p. 101. 2. Hindle<br />

et al., Charles Willson Peale and His World, p. 78. 3. Ibid.

4<br />

Charles Willson Peale<br />

(American, 1741–1827)<br />

The Reverend Joseph Pilmore, 1787<br />

Mezzotint engraving on paper, 7 1 /2 x 6 1 /4 inches (oval)<br />

Letterpress (around oval border): “The Reverend JOSEPH PILMORE<br />

Rector Of The United CHURCHES OF TRINITY, ST. THOMAS And<br />

ALL-SAINTS./painted and Engraved by C. W. Peale 1787.”<br />

Provenance: See plate 3.<br />

References: Charles Coleman Sellers, “Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson<br />

Peale,” in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 42, pt. 1 (Philadelphia:<br />

American Philosophical Society, 1952), no. 692; Robert Devlin <strong>Schwarz</strong>, A <strong>Gallery</strong><br />

Collects Peales, Philadelphia Collection XXXV (Philadelphia: <strong>Schwarz</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, 1987),<br />

no. 8; Wendy J. Shadwell, “The Portrait Prints of Charles Willson Peale,” in<br />

Eighteenth-Century Prints in Colonial America, ed. Joan D. Dolmetsch (Williamsburg,<br />

Va.: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1979), pp. 134–40<br />

Several years of postwar depression followed the end of the Revolutionary War. Although Charles Willson Peale was a<br />

popular artist during that time, portrait commissions could not support his family and their house at Third and Lombard<br />

streets, which he had purchased in 1780. In London, artists had enjoyed great success with engravings after their paintings.<br />

Peale decided that this could be a profitable endeavor for him, and so in 1787 he began to publish a series of mezzotint<br />

portraits. The first three engravings—of Franklin, Lafayette, and Washington—were followed by this print of Joseph<br />

Pilmore. The Pilmore portrait was not part of the original series, but after its advertisement in the Pennsylvania Packet (May<br />

18 and July 2, 1787), it became Peale’s most popular print. Although the artist had anticipated a series of a dozen engravings<br />

of famous Americans, he published only the first three and this portrait of Pilmore. The difficult process of producing and<br />

marketing the engravings without the services of the printmakers and printsellers available to artists in the London market<br />

limited the profitability of this “pioneer effort to establish printmaking in Philadelphia.” 1 This is one of six impressions of<br />

the Pilmore mezzotint known. 2<br />

Notes<br />

1. Edgar P. Richardson, “Charles Willson Peale’s Engravings in the Year of the National Crisis,” in Charles Willson Peale and His World by Edgar P.<br />

Richardson et al. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1973), p. 181. 2. Wendy J. Shadwell, “The Portrait Prints of Charles Willson Peale,” in Eighteenth-<br />

Century Prints in Colonial America, ed. Joan D. Dolmetsch (Williamsburg, Va.: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1979), pp. 134–40.

Charles Peale Polk<br />

The opportunity to study this pair of portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Herman Henry Schroeder by Charles Peale Polk almost two<br />

decades after first viewing them has led to a major reevaluation of their place within this artist’s oeuvre and a renewed<br />

recognition of their great visual strength and beauty. The intervening years have afforded the opportunity to see numerous<br />

works by Polk, a major non-academic painter active from the 1780s until the 1820s in the Middle Atlantic states. Based on<br />

a knowledge of almost 100 of his portraits (it is thought that he executed over 150) as well as on a greater familiarity with<br />

the works of the multitudinous painting members of the Peale family, the current discussion of this pair of portraits reflects<br />

a new and informed appreciation of Polk’s achievement as a painter. These portraits can now be seen as integral to<br />

understanding the development of Polk’s mature style and provide evidence of his eighteenth-century reputation as well as<br />

the regard given his work in recent American art history scholarship.<br />

Born to Robert Polk and Elizabeth Digby Peale in Annapolis, Maryland, and orphaned during the American Revolution, Polk<br />

was raised by his uncle, the noted artist Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), who educated him as a painter. Polk’s artistic<br />

career began in Philadelphia about 1785, around the same time he married Ruth Ellison, but by 1791 he had moved his<br />

family to Baltimore. Polk remained there for five years before moving west to Frederick, Maryland. During the subsequent<br />

five years as an itinerant painter in western Maryland and the northern Shenandoah Valley, Polk solidified his mature style.<br />

Abandoning academic traditions, his distinctive style emerged, combining a heightened palette and electric highlights with<br />

an exaggerated attenuation of the human form. The 1799 group of portraits of Isaac Hite, his wife and son Eleanor Conway<br />

Hite and James Madison Hite, as well as his in-laws James Madison Sr. and Eleanor Conway Madison (Belle Grove, The National<br />

Trust for Historic Preservation, Middletown, Virginia) are Polk’s acknowledged masterpieces and demonstrate his manner of<br />

presenting more about the sitter than a physical likeness. Polk’s style was to depict sitters with objects and in settings that<br />

portrayed their family relationships, business dealings, or political beliefs. In the case of Isaac Hite, for example, the portraitist<br />

declared the sitter’s support of the Republican Party, and Thomas Jefferson’s candidacy for President, by depicting Hite<br />

prominently holding a newspaper known for its Republican views. To visually reinforce Hite’s political ideals further, Polk<br />

was then commissioned to create a portrait of Jefferson. Polk arrived at Monticello with a letter of introduction from James<br />

Madison, Hite’s brother-in-law, and during November 1799 painted a portrait of Jefferson that was to become the source of<br />

at least five replicas. Which painting he delivered to Belle Grove, the Hite home, has not been determined. The portrait of<br />

Jefferson that once hung there left the possession of the Hite descendants following the Civil War.<br />

Within a year of completing the portrait of Jefferson (and of Jefferson’s election as President), Polk moved to Washington,<br />

D.C., seeking a government appointment, which he eventually received as a clerk in the United States Treasury Department.<br />

Through 1816 he painted occasional portraits of District residents, during which time he began working in verre églomisé,<br />

a type of reverse painting with gold leaf on glass. Polk married a second time following the death of Ruth Ellison Polk. His<br />

membership in the Baptist Church, begun in Philadelphia and continued in Maryland, led him to become one of the<br />

founding members of the First Baptist Church of Washington. After the death of his second wife (the widow<br />

Brockenbourgh) and two years after his third marriage (to Ellen Ball Downman), the couple and their only child relocated<br />

to land Ellen had inherited in Richmond County, Virginia, where Polk was to spend the last two years of his life on their<br />

farm. His death in 1831 was announced in Washington newspapers.

The portraits of Herman Henry Schroeder and Susannah Schwartz Schroeder were painted in either 1793 or 1794, while<br />

Polk was a resident of Baltimore. The artist presents a youthful couple, active in that community—a successful merchant<br />

and his wife. Polk’s basic stylistic elements are clearly seen in the beauty and charm of these works. The sitters’ images are<br />

unified as a pair by poses, palette, details of costume, props, and setting. Their poses in both portraits are specifically Polk’s<br />

own—the figures pulled up close to the canvas, seated comfortably before the painter, relaxed but still cordially formal. It<br />

is not known whether these portraits were executed in the artist’s studio, in a rented space, or at Wandsbeck, the home of<br />

the sitters. In any of these settings, Polk could have provided the furnishings for a portrait setting: chairs and tables, drapes,<br />

and a platform. The fact that similar chairs appear in other portraits suggests that they were part of the artist’s studio<br />

equipment. What is not usual for Polk, however, is the absence of background props such as draperies or architectural<br />

elements, suggesting that the Schroeders may have been painted in a studio set up by Polk in a rented space. Their bodies<br />

are positioned to form echoing brackets: she turns right toward him and he turns left toward her. All visual elements seem<br />

to have been selected to complement or contrast each sitter with or to the other: her salmon-colored gown to his green coat,<br />

her round table to his square-cornered table, her rosebud and book to his letter and hand-held chart. Each figure is seen<br />

against the same simple gray background of empty but luminous space.<br />

After thus unifying them as a couple Polk focuses attention on each figure. Susannah is placed at her husband’s right hand,<br />

historically a position of matrimonial subservience. She is attired in female finery, with an elaborate bonnet of cascading,<br />

sheer white fabric edged with ribbons and festooned with bows. Her youth, evident in her facial features, is complemented<br />

by the dark ringlets on her shoulders and the expanse of neck and firm bosom above a plunging neckline, barely kept modest<br />

by a white fichu pulled down and restrained by a bow almost at her ribbon-enwrapped waist. Those white v-forms lead the<br />

viewer’s eye to her hands, demurely resting in a lap of sprigged, salmon-colored fabric. The quietness of her hands<br />

accentuates the delicate rosebud held between her left forefinger and thumb. Brought to nearly equal prominence by the<br />

direction of those v-forms is her gold-banded finger. The budding flower and wedding band not only symbolize her<br />

youthfulness and state of matrimony but suggest her fertility.<br />

Susannah Schwartz Schroeder’s ties to Herman Henry Schroeder are symbolically reinforced by more than the gold band.<br />

Their linkage is suggested visually by a number of coy elements painted by Polk, such as the repetition of the rosebud<br />

embroidered or printed again and again in the patterning of her gown. Sprig after sprig arches, embroidered or printed leaf<br />

and stem forms recalling buds and leaves, all colored the same hue of green as in her husband’s coat.<br />

In his portrait Herman Henry Schroeder sits upright, declaring his masculinity in the greater rigidity and strength of his pose.<br />

As with Susannah, the depiction of his clothing is filled with a wealth of specific details that not only declare his position in<br />

their relationship but also visually unify his image. The green of his coat is echoed in the delightful detail of the stitching on<br />

his yellow vest, which is set off against the white ruffles of the shirt and lace-edged jabot tied in a bow at his neck.<br />

Polk has carefully observed and recorded Schroeder’s distinctive facial features of high cheekbones, arched eyebrows, and<br />

long, thin nose above a small mouth. Clearly, Schroeder was as fashion conscious in his dress as he was reputed to have been

5<br />

Charles Peale Polk<br />

(American, 1767–1822)<br />

Susannah Schwartz (Mrs. Herman Henry) Schroeder (1767–1794), 1793–94<br />

Oil on canvas, 36 x 29 1 /2 inches<br />

Provenance: Descended in the family of the sitter<br />

Exhibited: Corcoran <strong>Gallery</strong> of Art, Washington, D.C., Charles Peale Polk, 1767–1822: A<br />

Limner and His Likenesses (July 18–Sept. 6, 1981), no. 68<br />

Recorded: Linda Crocker Simmons, Charles Peale Polk, 1767–1822: A Limner and His<br />

Likenesses (Washington, D.C.: Corcoran <strong>Gallery</strong> of Art, 1981), p. 46, no. 68 (repro.)<br />

Reference: Linda Crocker Simmons, “Politics, Portraits and Charles Peale Polk,” in The Peale<br />

Family: Creation of a Legacy, 1770–1870, ed. Lillian B. Miller (New York: Abbeville Press, 1996)<br />

Note: These works retain what appear to be their original black and gilt frames, as well as<br />

some of the hanging rings at the top back of both frames.

6<br />

Charles Peale Polk<br />

(American, 1767–1822)<br />

Herman Henry Schroeder (1764–1839), 1793–94<br />

Oil on canvas, 36 x 29 inches<br />

Provenance: Descended in the family of the sitter<br />

Exhibited: Corcoran <strong>Gallery</strong> of Art, Washington, D.C., Charles Peale Polk, 1767–1822: A Limner<br />

and His Likenesses (July 18–Sept. 6, 1981), no. 69<br />

Recorded: Linda Crocker Simmons, Charles Peale Polk, 1767–1822: A Limner and His Likenesses<br />

(Washington, D.C.: Corcoran <strong>Gallery</strong> of Art, 1981), p. 46, no. 69 (repro.)<br />

Reference: Linda Crocker Simmons, “Politics, Portraits and Charles Peale Polk,” in The Peale<br />

Family: Creation of a Legacy, 1770–1870, ed. Lillian B. Miller (New York: Abbeville Press, 1996)

in the architecture of his residence. He wears his hair in a fashionable French manner, powdered white, curled at the ears,<br />

and pulled back to a ponytail on his back—the tiny point of the black ribbon visible over his left shoulder. Such careful<br />

observation and depiction lend credibility to the belief that very little that was represented by Polk was by chance or without<br />

a function or purpose related to our understanding or appreciation of the image. Unfortunately, unlocking the meaning of<br />

the various elements and details included in this late-eighteenth-century portrait may not be as easy as describing them.<br />

Herman Henry Schroeder holds a piece of paper in his right hand, lying in his lap. The paper has a central area of painted<br />

bars surmounted by a star shape of lines, maybe in pen and ink, with his initials and “No 27” inscribed:<br />

Evidently, this paper and the inscriptions and colors on it had very specific meanings for the sitter. It is known that<br />

Schroeder was born in Wandsbeck, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, in 1764 and that he died in Baltimore on July 24, 1839.<br />

Thus, the first date given is clearly a reference to his birth, but the symbolic importance of the stripe of ochre to the right<br />

of the date has not yet been determined. It is evident that the following dates all represent significant events in Schroeder’s<br />

life and that this piece of paper is not just a visualization of Schroeder’s personal genealogy but also a visual and symbolic<br />

outline of the married life of the two subjects. The birth of their fourth son would not take place until March 4, 1794, which<br />

is foretold by the rosebud in Susannah’s portrait, another genealogical event linking the young couple.<br />

Date<br />

1764<br />

1765<br />

1785<br />

1785<br />

1787<br />

1789<br />

1791<br />

Color<br />

ochre<br />

dark green<br />

scarlet<br />

dark blue<br />

dark green<br />

blue-green<br />

black<br />

Significant Event<br />

birth<br />

baptism<br />

emigration<br />

marriage<br />

birth of Herman Henry, Jr.<br />

birth of Frederick Henry<br />

birth of Thomas Charles<br />

It is possible that the forthcoming birth, symbolically foretold in the paired images of the sitters, may have been the reason for<br />

the creation of this pair of portraits in late 1793 or very early 1794. These paintings are a portrayal of the Schroeder family and<br />

possibly a statement intended to link the sitters with preceding generations. One can argue that the slip of paper Schroeder<br />

holds may have been intended to be enclosed in the open letter lying on the table. This slip appears to be creased along the<br />

long sides of the colors, and the creases correspond to the creasing on the sheet of paper. Uncharacteristically for Polk, the<br />

writing on that sheet of paper is illegible; however, it has the form of a letter, which could be sealed and sent with the family<br />

genealogy folded inside. Further speculation might lead one to consider the number at the top of the hand-held slip to be<br />

numbered as the 27th generation of the Schroeder family, a possibility that would require extensive additional research to<br />

support. Until such information is available to prove or disprove such a supposition, the mystery of the number 27 will remain.<br />

—Linda Crocker Simmons

7<br />

Thomas Birch<br />

(American, born England, 1779–1851)<br />

English Setter, 1813<br />

Oil on panel, 9 x 11 inches<br />

Signed and dated at lower right: “T Birch/1813”<br />

Inscribed in ink on canvas verso: “Painted by Thos Birch.1813. Phila.”<br />

Provenance: <strong>Schwarz</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> by 1992; private collection until 2003<br />

Exhibited: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Third Annual<br />

Exhibition (1813), no. 121<br />

Illustrated: F. Turner Reuter, Jr., A History of American Animal and Sporting Art,<br />

1750–1950 (Lanham, Md.: Derrydale Press, forthcoming)<br />

Thomas Birch, son of the well-known enamelist, watercolorist, and engraver William Birch (1755–1834), was one of early<br />

America’s most important marine artists and the founder of the Philadelphia tradition of marine painting. Born in England,<br />

he came to the United States with his family when he was fifteen. Birch learned the technical skills of engraving from his<br />

father, and in 1799 they published their widely known series of Philadelphia views. In addition to his father’s instruction,<br />

the young artist was able to study paintings by important English and European artists that his father owned. In 1795<br />

Thomas Birch entered two small watercolors in the Columbianum in Philadelphia, the first public art exhibition in the<br />

United States. From 1812 to 1817 Birch was curator at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he exhibited<br />

almost annually from 1811 until his death in 1851. Among his more famous students were George R. Bonfield<br />

(1802–1898), Thomas Cole (1801–1848), and James Hamilton (1819–1878).<br />

Although Birch is best known for his views of the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers, his marine views of the mid-Atlantic and<br />

New England coasts, and his ship portraits and naval battles, he also painted many landscapes that feature country houses<br />

(the subject of another print series by the two Birches) or recreational activities such as sleighing (see plate 14) and hunting.<br />

Dog portraits were an uncommon subject for American artists in the early nineteenth century, but a very popular one in the<br />

Birches’ native England.

8<br />

Adolph-Ulric Wertmüller<br />

(American, born Sweden, 1751–1811)<br />

Portrait of Elisabeth Henderson Wertmüller, 1801<br />

Oil on panel, 6 1 /2 x 5 1 /4 inches (oval)<br />

Signed and dated at left center: “A.W./1801”<br />

Inscribed in pencil on panel verso: “picture portrait of Maria R. Saymens/Date<br />

about 1780 [sic]” 1<br />

Provenance: <strong>Schwarz</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, 1997; Pennsylvania private collection, 1998–2002<br />

Recorded (probably): Adolph-Ulric Wertmüller, “Notte de tous mes ouvrages finis<br />

. . . pour les années 1780–1801”: “15 Aout [1801]—Fini le portrait de ma femme<br />

Elisabeth Henderson, [ . . . ] de 6 pouces sur 5 pouces, sur bois en ovale.” 2<br />

The life and travels of the Swedish-born portraitist, miniaturist, and history painter Adolph-Ulric Wertmüller reflected the<br />

changing times in which he lived. Wertmüller began his studies in painting at the Art Academy in his native Stockholm with<br />

Lorentz Pasch the Younger (1733–1805), but in 1772 he moved to Paris, a more sophisticated and cosmopolitan artistic<br />

center. In Paris he studied first with his cousin Alexander Roslin (1718–1793), an established portraitist in the French<br />

capital, and then with Roslin’s friend, the influential French painter Joseph-Marie Vien (1716–1809). 3 When Vien became<br />

head of the French Academy in Rome, Wertmüller followed Vien to this center of western artistic culture, where he studied<br />

the great works of antiquity, honed his perspective skills, and began to produce large-scale canvases. Returning to Paris in<br />

1779, Wertmüller’s growing success in portraiture and history painting attracted the attention of King Gustaf III of Sweden.<br />

Although Wertmüller remained in Paris, he was elected to the Swedish Academy and was named the King’s “First Painter.”<br />

In 1784 Wertmüller was elected to the French Royal Academy, and in 1785 he exhibited his large portrait Queen Marie<br />

Antoinette Walking in the Trianon Park with Two of Her Children (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm). Despite his honors<br />

Wertmüller did not find commissions forthcoming in Paris, and in 1788 he left for Bordeaux, where his skills as a portraitist<br />

were in greater demand and where he enjoyed significant financial success. In 1790, unsettled by the upheavals in<br />

Revolutionary France, Wertmüller sought professional opportunities in Spain. However, by 1794 he was frustrated with<br />

patronage in both Madrid and Cadiz, and he availed himself of an opportunity to travel to America. Although neither<br />

Wertmüller nor his friend and traveling companion Henrik Gahn came to America with the intention of staying, both men<br />

eventually settled here and became citizens. 4<br />

Wertmüller may have been the most well-trained artist to arrive on American shores in the 1790s, and his artistic abilities<br />

were readily acknowledged upon his arrival in Philadelphia. By December 1794 he had painted several members of Congress<br />

as well as President Washington. 5 His interest in the Philadelphia art community and the creation, by its artists, of America’s<br />

first art academy, the Columbianum, is attested to by his signature on documents relating to the creation of that<br />

organization. Wertmüller also found the city congenial to his freedom-loving politics and, on a personal level, he made<br />

friends within the area’s substantial Swedish community. Most important among these friends was Elisabeth (Betsey)<br />

Henderson, who later would become his wife. Betsey was the granddaughter of the Swedish immigrant artist Gustavus<br />

Hesselius (1682–1755) and the niece of the artist John Hesselius (1728–1778), who had given Charles Willson Peale (see<br />

plates 3 and 4) his first lessons in the art of painting. 6 Late in 1796, Wertmüller’s courtship of Betsey was interrupted when<br />

he was forced to return to Europe because his finances, which he had entrusted to a relative who turned out to be<br />

unscrupulous, were found to be in shambles. After much difficulty and disappointment in Europe, Wertmüller returned to<br />

Philadelphia with his paintings, books, and drawings, but little cash.

actual size<br />

The most significant work Wertmüller returned with from Europe was his Danae and the Shower of Gold (Nationalmuseum,<br />

Stockholm). A lifesize painting of a female nude he had done in Paris in 1787, the work was a prime example of Rococo<br />

Classicism. The subject of the Danae was taken from the ancient classic, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and the meticulous modeling<br />

of her nubile form was admired by the important French artist Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), who had also been a<br />

student of Wertmüller’s master, Vien. 7 Despite hesitations about its risqué subject matter, Danae’s admirers on this side of the<br />

Atlantic were numerous. Charles Willson Peale recommended it to the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764–1820) as<br />

being “very worth while your seeing.” 8 And Charles’s son Rembrandt Peale (1778–1860), who later recalled that “bustling<br />

connoisseurs declared that no American painter could ever equal the beauty of its coloring,” assisted Wertmüller in setting up<br />

and promoting the picture’s exhibition. Mondays were typically designated as days for ladies to view the work without the<br />

embarrassment of male companionship. 9 In 1803 the Wertmüllers moved to Naaman’s Creek on the banks of the Delaware<br />

River to dedicate themselves to farming, but, ironically, the income from their agricultural pursuits was eclipsed by the more

substantial sum generated by the display of the Danae. 10 This financial fact did not escape the notice of Rembrandt Peale,<br />

who, after Wertmüller’s death in 1811, unsuccessfully attempted to purchase the “beautiful and brilliant” picture for display<br />

in his Apollodorian <strong>Gallery</strong>. 11 After changing hands several times during the next few years, the painting was purchased by<br />

the artist John Wesley Jarvis (1780–1840), who exhibited it at his New York painting rooms. It was here that the young Henry<br />

Inman (1801–1846) encountered Wertmüller’s masterpiece and was inspired to become a painter. 12<br />

In the small oval portrait of a young woman pictured here, Wertmüller deftly merged his skills as portraitist and history<br />

painter. The specificity of the subject’s likeness is softened by the glow of the sun rising from the shadows of night, and her<br />

diaphanous, high-waisted, white muslin shift suggests an affinity with the ancient goddesses, the Venuses and the Auroras that<br />

the artist was so adept at rendering. 13 Wertmüller’s use of neoclassical garb was a continuation of a European portrait<br />

convention, particularly popular in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, that portrayed women as goddesses or<br />

characters from Classical literature. As a portrait type, it also conforms to the tradition of partially nude images of wives or<br />

mistresses that were designed to celebrate the subject’s physical charms. 14 Wertmüller’s initials and the date 1801, clearly<br />

inscribed on the tree trunk to the right of the figure, establishes the fact that this portrait was among the first works he painted<br />

upon his return to America. It has been suggested that the intimacy and tenderness of the image, along with the placement<br />

of his initials on the tree, a site where lovers traditionally inscribed their initials, are visual clues to the artist’s amorous link<br />

to his subject. 15 This supposition correlates with the fact that on his return to Philadelphia from Europe in November 1800,<br />

Wertmüller lost little time in fulfilling his pledge of marriage to Elisabeth Henderson, and the couple was wed by the Rev.<br />

Nicholas Collin in Old Swedes’ Church in January 1801. During the following summer, the artist recorded in his “Notte de<br />

tous mes ouvrages finis . . . pour les années 1780–1801” that he had completed oval portraits on panel of himself and his<br />

wife, each measuring 6 by 5 inches. 16 This exact correspondence in date, medium, and dimensions strongly argues for the<br />

identification of the portrait of a young woman as an image of Betsey Henderson Wertmüller. 17 The medium, size, and format<br />

of these two portraits also correspond exactly to those of the two portraits Wertmüller painted of his sisters in Stockholm in<br />

1799, which he brought back with him to Philadelphia. 18 These portraits, therefore, may have formed a family group.<br />

The sunrise behind Betsey may be seen as a metaphor for the beginning of the Wertmüllers’ life together in the artist’s newly<br />

adopted country. But Betsey’s neoclassical attire may be seen as both metaphoric and real, since French fashions “à l’antique”<br />

were the height of fashion in Philadelphia in 1801. The city’s influential literary magazine, the Port Folio, noted the<br />

popularity of the short “Titus” hairstyle Betsey sports, as well as the vogue for wearing pearls in the hair. 19 The French<br />

antique style inspired low necklines, high waists, short sleeves, narrow skirts, and sheer fabrics, and the sight of such<br />

“unchaste costume” led to much critical and satiric commentary. While most Philadelphia women selected only certain<br />

elements of this style, there were those who presented themselves as unabashedly “fashionable nudes” and adopted the “wet<br />

and adhesive drapery” of neoclassicism. 20 The extremes of this style were favored by such beautiful, wealthy, and<br />

cosmopolitan young women as Maria Bingham, daughter of the Philadelphia merchant William Bingham, and Elizabeth<br />

Patterson Bonaparte, the young American wife of Jerome Bonaparte. 21 While Betsey Henderson Wertmüller undoubtedly<br />

presented herself more chastely in public, the high fashion of the day and Wertmüller’s European perspective merge in this<br />

intimate and gentle portrait that mixes likeness, imagination, and the projection of hope for the future. 22<br />

—Carol Eaton Soltis<br />

Notes<br />

1. The inscription penciled on the back of this portrait contradicts the information on the front. The inscription tentatively states that the image was<br />

created “about” 1780, a date twenty years prior to the date of 1801, which is inscribed on the tree trunk to the left of the figure. The date of 1780 also<br />

is inconsistent with the subject’s costume. Therefore, although the provenance of this picture may be linked to a Maria Saymens and her descendants, it<br />

is unlikely that the portrait is an image of Maria Saymens. No references exist to individuals named Saymens in Wertmüller’s records from either his<br />

European or his American years. If the evidence supporting the identification of the portrait’s subject as Elisabeth Henderson Wertmüller, the artist’s<br />

wife, is correct, the portrait may have been obtained by a member of the Saymens family at one of the several sales of Wertmüller’s studio and the

Wertmüllers’ household items that occurred after the death of the artist in 1811 or the death of his wife in 1812. 2. Wertmüller’s “Notte de tous mes<br />

ouvrages finis . . . pour les années 1780–1801” is in the Royal Library, Stockholm. 3. Wertmüller’s earliest training was in drawing and sculpture with<br />

Pierre-Hubert Larcheveque (1721–1778). Franklin D. Scott, Wertmüller: Artist and Immigrant Farmer (Chicago: Swedish Pioneer Historical Society,<br />

1963), p. 2. 4. Gahn’s uncle was the Swedish consul to Spain and arranged passage to and from Philadelphia for his nephew and Wertmüller. In 1797<br />

Henrik Gahn, who later became a successful American businessman, served as Swedish consul in New York. Scott, Wertmüller, p.5. 5. For a list of<br />

Wertmüller’s works executed in Philadelphia between 1794 and 1796, see Michel N. Benisovich, “Wertmüller et son livre de raison intitulé la ‘Notte,’”<br />

Gazette des Beaux Arts, ser. 6, vol. 48 (July–Aug. 1956), pp. 58–60. 6. Gustavus Hesselius arrived in Delaware in 1711, but soon after he settled in<br />

Philadelphia. His son, John, settled in Maryland. In 1763 the young Maryland-born saddler Charles Willson Peale gave John Hesselius one of his “best<br />

saddles with its complete furniture” in return for three lessons in portrait painting. Peale stated that these lessons “infinitely lightened the difficulties of<br />

the new art” for him, and he shortly thereafter advertised himself as a painter. Lillian B. Miller, ed., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His<br />

Family, vol.1 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1983), p. 33. 7. Scott, Wertmüller, p.5. 8. Charles Willson Peale to B. H. Latrobe,<br />

Philadelphia, May 13, 1805, Peale-Sellers Papers, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia. Lillian B. Miller, ed., The Selected Papers of Charles<br />

Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 2, pt. 2 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988), p. 834. 9. Rembrandt Peale, “Reminiscences, Adolph-<br />

Ulric Wertmüller,” The Crayon, vol. 2, no. 14 (Oct. 3, 1855), p. 207. Although the painting had been available to be seen since its arrival late in 1800,<br />

its first formal display was established in the fall of 1806. Wishing to stop the random flow of people coming to see the picture at his home at Naaman’s<br />

Creek, Wertmüller placed the Danae on permanent public exhibition in Philadelphia. An advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette on Sept. 25, 1806,<br />

states that the painting was on view Mondays through Saturdays, and the admission fee was 25 cents. See Michel N. Benisovich, “Further Notes on A.-<br />

U. Wertmüller in the United States and France,” Art Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 1 (spring 1963), p. 9. 10. When Wertmüller’s estate was auctioned in<br />

1812, the Philadelphia auctioneer John Dorsey advertised the Danae as earning “$800 per annum without solicitude.” See Poulson’s American and Daily<br />

Advertiser, Apr. 16–19, 1812. When the painting first arrived in the city, it brought as much as $1,100 per annum. In 1803 Wertmüller purchased a<br />

farm at Naaman’s Creek, Delaware, about 20 miles south of Philadelphia. For his life as a farmer, see the Naaman’s Creek Diary, translated from the<br />

French manuscript, “Journal de la terre situé à Naaman’s Creek,” (Royal Library, Stockholm) by Franklin D. Scott and Rosamond Porter in Scott,<br />

Wertmüller, pp. 33–173. 11. Peale, “Wertmüller,” p. 207. Peale was outbid, but in response, he painted his own large exhibition picture with a female<br />

nude as its central feature. For a discussion of Peale’s painting Jupiter and Io and its relationship to Wertmüller’s painting, See Carol Eaton Soltis, “In<br />

Sympathy with the Heart: Rembrandt Peale, an American Artist and the Traditions of European Art,” Ph.D. diss. (University of Pennsylvania, 2000),<br />

pp. 290–334. 12. H. T. Tuckerman on Inman’s experience, as quoted in Michel N. Benisovich, “The Sale of the Studio of Adolph-Ulrich Wertmüller,”<br />

Art Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 1 (spring 1953), pp. 33, 36. Tuckerman described the painting as “one of the most exquisite pieces of flesh painting which<br />

has emanated from the French school of which the Swedish artist was essentially a votary.” The Danae was given to the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm,<br />

in 1913 by its American owner, J. E. Heaton of New Haven, Conn. See Benisovich, “The Sale,” p. 36. 13. For the numerous figures from Classical<br />

mythology he painted, see Benisovich, “The Sale,” pp. 24, 27–30; Benisovich, “Further Notes on A.-U. Wertmüller,” pp. 13, 21; Benisovich,<br />

“Wertmüller et son livre de raison intitulé la ‘Notte,’” pp. 51, 59, 63. 14. For an example of an American miniature portrait of this type painted c.<br />

1805, see Robin Jaffe Frank, Love and Loss, American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1999), pp. 195,<br />

fig. 100. For European examples, see Jacqueline du Pasquier, “La Situation de la miniature à Bordeaux,” in l’âge d’or du petit portrait (Paris: Réunion<br />

des Musées Nationaux, 1995), pp. 57, 69. 15. In regard to this portrait, Dr. Ellen Miles of the National Portrait <strong>Gallery</strong> (Washington, D.C.) cited<br />

the tradition in European art of showing lovers’ initials on tree trunks. Ellen Miles to David Cassedy of the <strong>Schwarz</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, in a telephone conversation<br />

on April 16, 1998. See American Paintings (Philadelphia: <strong>Schwarz</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, 1998), no. 3. 16. Wertmüller’s notes read: “30 Juillet—Fini Mon Portrait<br />

pour Moi en petit de 6 pouces sur 5 pouces sur bois en ovale.” “15 Aout—Fini le portrait de ma femme Elisabeth Henderson, en petit pendent [sic]<br />

pour le mien ci-dessus, de 6 pouces sur 5 pouces, sur bois en ovale.” According to the “Notte,” the only oval panel portrait of a woman he painted in<br />

1801 was the portrait of Betsey. The “Notte” actually included works painted in 1802. It is fully transcribed in Benisovich, “Wertmüller et son livre de<br />

raison intitulé la ‘Notte,’” p. 63. The measurements of 5 x 6 inches and the medium of a wooden oval were frequently employed by Wertmüller. 17.<br />

The pendant portrait of Wertmüller is presently unlocated. Wertmüller was 50 years old when he married, and he wrote home to his family that Betsey<br />

was “a most respectable and kindly young woman.” Scott, Wertmüller, p. 14. Wertmüller died at age 61 on Oct. 5, 1811. Betsey outlived her husband<br />

by only a few months; she died on Jan. 19, 1812. Betsey’s birth date is unknown, and there are conflicting comments in the Wertmüller literature in<br />

regard to it. For undated miniature (on copper) likenesses of Wertmüller and Betsey, see Benisovich, “The Sale,” p. 25. This portrait of Betsey appears<br />

to resemble the likeness in Portrait of Elisabeth Henderson Wertmüller. Both portraits are also similar to the portrait painted by Wertmüller in Philadelphia<br />