the maintenance of species-richness in plant communities

the maintenance of species-richness in plant communities

the maintenance of species-richness in plant communities

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

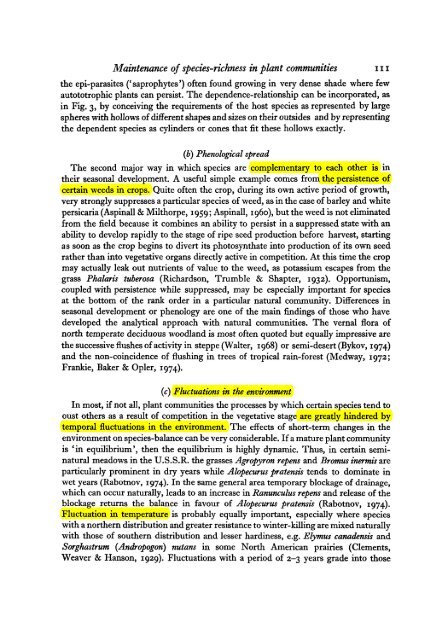

Ma<strong>in</strong>tenance <strong>of</strong> <strong>species</strong>-<strong>richness</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>plant</strong> <strong>communities</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> epi-parasites (‘saprophytes’) <strong>of</strong>ten found grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> very dense shade where few<br />

autototrophic <strong>plant</strong>s can persist. The dependence-relationship can be <strong>in</strong>corporated, as<br />

<strong>in</strong> Fig. 3, by conceiv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> requirements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> host <strong>species</strong> as represented by large<br />

spheres with hollows <strong>of</strong> different shapes and sizes on <strong>the</strong>ir outsides and by represent<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> dependent <strong>species</strong> as cyl<strong>in</strong>ders or cones that fit <strong>the</strong>se hollows exactly.<br />

I11<br />

(b) Phenological spread<br />

The second major way <strong>in</strong> which <strong>species</strong> are complementary to each o<strong>the</strong>r is <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir seasonal development. A useful simple example comes from <strong>the</strong> persistence <strong>of</strong><br />

certa<strong>in</strong> weeds <strong>in</strong> crops. Quite <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>the</strong> crop, dur<strong>in</strong>g its own active period <strong>of</strong> growth,<br />

very strongly suppresses a particular <strong>species</strong> <strong>of</strong> weed, as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> barley and white<br />

persicaria (Asp<strong>in</strong>all & Milthorpe, 1959; Asp<strong>in</strong>all, 1960), but <strong>the</strong> weed is not elim<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

from <strong>the</strong> field because it comb<strong>in</strong>es an ability to persist <strong>in</strong> a suppressed state with an<br />

ability to develop rapidly to <strong>the</strong> stage <strong>of</strong> ripe seed production before harvest, start<strong>in</strong>g<br />

as soon as <strong>the</strong> crop beg<strong>in</strong>s to divert its photosynthate <strong>in</strong>to production <strong>of</strong> its own seed<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>in</strong>to vegetative organs directly active <strong>in</strong> competition. At this time <strong>the</strong> crop<br />

may actually leak out nutrients <strong>of</strong> value to <strong>the</strong> weed, as potassium escapes from <strong>the</strong><br />

grass Phalaris tuberosa (Richardson, Trumble & Shapter, I 932). Opportunism,<br />

coupled with persistence while suppressed, may be especially important for <strong>species</strong><br />

at <strong>the</strong> bottom <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rank order <strong>in</strong> a particular natural community. Differences <strong>in</strong><br />

seasonal development or phenology are one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> those who have<br />

developed <strong>the</strong> analytical approach with natural <strong>communities</strong>. The vernal flora <strong>of</strong><br />

north temperate deciduous woodland is most <strong>of</strong>ten quoted but equally impressive are<br />

<strong>the</strong> successive flushes <strong>of</strong> activity <strong>in</strong> steppe (Walter, 1968) or semi-desert (Bykov, 1974)<br />

and <strong>the</strong> non-co<strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> flush<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> trees <strong>of</strong> tropical ra<strong>in</strong>-forest (Medway, 1972;<br />

Frankie, Baker & Opler, 1974).<br />

(c) Fluctuations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment<br />

In most, if not all, <strong>plant</strong> <strong>communities</strong> <strong>the</strong> processes by which certa<strong>in</strong> <strong>species</strong> tend to<br />

oust o<strong>the</strong>rs as a result <strong>of</strong> competition <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> vegetative stage are greatly h<strong>in</strong>dered by<br />

temporal fluctuations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment. The effects <strong>of</strong> short-term changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

environment on <strong>species</strong>-balance can be very considerable. If a mature <strong>plant</strong> community<br />

is ‘<strong>in</strong> equilibrium’, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> equilibrium is highly dynamic. Thus, <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> sem<strong>in</strong>atural<br />

meadows <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.S.S.R. <strong>the</strong> grasses Agropyron repens and Bromus <strong>in</strong>ermis are<br />

particularly prom<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong> dry years while Alopecurus patensis tends to dom<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong><br />

wet years (Rabotnov, 1974). In <strong>the</strong> same general area temporary blockage <strong>of</strong> dra<strong>in</strong>age,<br />

which can occur naturally, leads to an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> Ranunculus repens and release <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

blockage returns <strong>the</strong> balance <strong>in</strong> favour <strong>of</strong> Alopecurus patensis (Rabotnov, 1974).<br />

Fluctuation <strong>in</strong> temperature is probably equally important, especially where <strong>species</strong><br />

with a nor<strong>the</strong>rn distribution and greater resistance to w<strong>in</strong>ter-kill<strong>in</strong>g are mixed naturally<br />

with those <strong>of</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn distribution and lesser hard<strong>in</strong>ess, e.g. Elymus canadensis and<br />

Sorghastrum (Andropogon) nutans <strong>in</strong> some North American prairies (Clements,<br />

Weaver & Hanson, 1929). Fluctuations with a period <strong>of</strong> 2-3 years grade <strong>in</strong>to those