Canadian Intelligent Super Corridor - Smart Inland Port Network

Canadian Intelligent Super Corridor - Smart Inland Port Network

Canadian Intelligent Super Corridor - Smart Inland Port Network

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

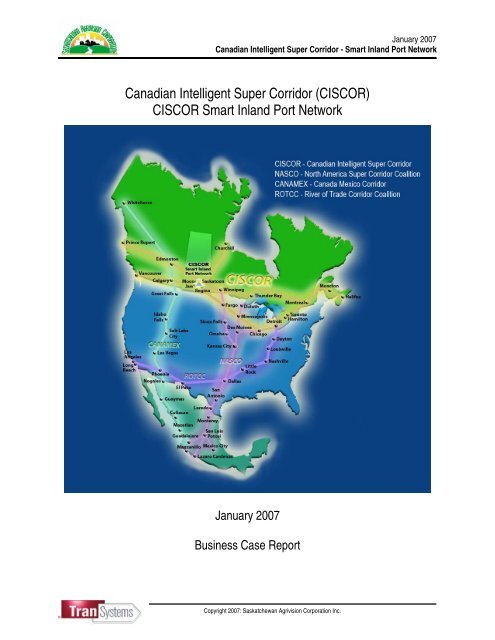

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> (CISCOR)<br />

CISCOR <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

January 2007<br />

Business Case Report<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc.

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Funding for this business case project was provided by Western Economic Diversification<br />

Canada, Saskatchewan Agriculture and Food, and the Saskatchewan Canola Development<br />

Commission.<br />

This project was administered by Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. Guidance on this<br />

project was supplied by the Saskatchewan Trade and Export Partnership, Regina Regional<br />

Economic Development Authority, Moose Jaw Regional Economic Development Authority and<br />

the Saskatoon Regional Economic Development Authority.<br />

Special Thanks to:<br />

Ken Hoffman, Kansas City <strong>Smart</strong><strong>Port</strong><br />

This report was prepared by:<br />

John Vickerman, Principal<br />

Christopher Matson, Project Manager<br />

Shannon McLeod, Transportation Planner<br />

TranSystems Corporation Consultants<br />

150 Boush Street, Suite 1000,<br />

Norfolk, VA USA 23510<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc.

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Table of Contents<br />

Executive Summary - French....................................................................................................................E-1<br />

Executive Summary - English................................................................................................................. E-11<br />

Introduction .............................................................................................................................................IN-1<br />

Section 1: Global Industry Trends and Conditions................................................................................... 1-1<br />

Growth in Containerized Trade and Asian Market .................................................................. 1-1<br />

Increasing Vessel Size and Industry Consolidation ................................................................ 1-2<br />

Panama Canal Expansion ...................................................................................................... 1-3<br />

North American <strong>Port</strong> and Intermodal Congestion ................................................................... 1-3<br />

Driving Forces Behind <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> Development .................................................................... 1-5<br />

Section 2: <strong>Canadian</strong> Solution ................................................................................................................. 2-1<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> Trade Partners and Statistics ................................................................................ 2-1<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Port</strong>s and Containerization Growth........................................................................ 2-2<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> Railways and Intermodal Traffic ............................................................................ 2-7<br />

Canada’s Strategic Location................................................................................................ 2-10<br />

Pacific and Atlantic Gateway Strategies ............................................................................... 2-13<br />

Section 3: The Prairie Region – The Saskatchewan Advantage ............................................................. 3-1<br />

Benefits................................................................................................................................... 3-1<br />

Challenges.............................................................................................................................. 3-4<br />

Section 4: <strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Port</strong> – Bringing It All Together ............................. 4-1<br />

Agile <strong>Port</strong> System ................................................................................................................... 4-2<br />

Logistic Management System................................................................................................. 4-2<br />

<strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> Services................................................................................................................ 4-3<br />

Benefits to Carriers, <strong>Port</strong>s and Shippers................................................................................. 4-8<br />

Section 5: Case Studies .......................................................................................................................... 5-1<br />

Winnipeg, Manitoba................................................................................................................ 5-1<br />

CN Edmonton Grain Distribution Centre................................................................................. 5-3<br />

Kamloops Intermodal Container Facility ................................................................................. 5-4<br />

Northern Plains Commerce Centre......................................................................................... 5-5<br />

Minnesota North Star Rail Intermodal LLC ............................................................................. 5-6<br />

<strong>Inland</strong> International <strong>Port</strong> of Dallas........................................................................................... 5-8<br />

Section 6: Market Assessment ................................................................................................................ 6-1<br />

West Coast Trade Growth ...................................................................................................... 6-2<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> Trans-Pacific Trade Flows...................................................................................... 6-3<br />

<strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong> Potential Market and Prospective Throughput ............................. 6-5<br />

Section 7: Cost Analysis – A Business Case........................................................................................... 7-1<br />

Import Containerized Trade .................................................................................................... 7-1<br />

Containerization of Export Bulk Products ............................................................................... 7-2<br />

Conclusion, Recommendations and References................................................................................... CR-1<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc.

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Sommaire exécutif<br />

Les exportations et importations ont dépassé les 10 billions de dollars en 2005-06. La majorité des<br />

nouveaux navires porte-conteneurs sur les cinq prochaines années seront des navires post-Panamax<br />

prêts à transporter des marchandises de la Chine, du sud-est de l’Asie et de l’Inde vers des ports<br />

nord-américains déjà poussés à la limite de leur capacité. Le Canal panama approche son taux maximum<br />

d’opération et le réseau de transport américain se démène pour répondre à une augmentation annuelle<br />

prévue de 15% du trafic de contenants. En réponse à la croissance raide dans le commerce nordaméricain,<br />

les changements dans la chaîne d’approvisionnement mondiale de marchandises, et la<br />

congestion accrue dans les ports américains et le long du système multimodal, les expéditeurs redirigent<br />

maintenant de plus en plus de marchandises via les ports canadiens.<br />

La solution canadienne<br />

En tant que premier port d’escale nord-américain sur la route trans-Pacifique de l’Asie et la route trans-<br />

Atlantique de l’Europe, le Canada a l’occasion de développer un réseau sophistiqué de distribution<br />

multimodale pour desservir les zones de consommation croissantes dans le Midwest des États-Unis et au<br />

Canada. Le Canada peut servir de point de passage nord-américain au carrefour de trois réseaux de<br />

commerce puissants et itinérants : l’Accord de libre-échange nord-américain (ALENA) nord-sud, l’ALENA<br />

européen et la route trans-Pacifique hautement utilisée. Le résultat désiré est un corridor de transport de<br />

marchandises en direct qui transporte des marchandises des ports aux chemins de fer et autoroutes et<br />

vers un centre de logistique de port intérieur qui dessert tous les marchés nord-américains.<br />

Puisque les ports de Vancouver et de Prince Rupert sont situés sur la côte ouest du Canada, et que les<br />

ports de Halifax, du détroit de Canso et de Montréal sont sur la côté Est, il y a des avantages distincts en<br />

faveur d’une stratégie intégrée nationale multimodale pour le Canada en tant que nation. Ce pont terrestre<br />

transcontinental naissant et le port intérieur central judicieux pour desservir les marchés américains et<br />

canadiens des océans Atlantique et Pacifique seraient avantageux pour les ports impliqués, le chemin de<br />

fer et les lignes maritimes, les grands détaillants et la nation.<br />

Illustration SE-1. Réseau multimodal canadien<br />

Source: TranSystems, Association des chemins de fer du Canada<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 1

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

La région des Prairies : les avantages de la Saskatchewan<br />

La Saskatchewan est le carrefour du transport de la partie nord du continent nord-américain, avec des liens<br />

dans toutes les directions. Son emplacement idéal et son accès central au réseau de logistique des<br />

marchandises font de la Saskatchewan un site idéal pour l’établissement d’un complexe portail intérieur<br />

prospère, loin des lieux de congestion.<br />

La proximité géographique de la province aux centres de population nord-américains, à moins de deux<br />

jours de route de 80 millions de personnes au Canada et aux États-Unis, est appuyée davantage par un<br />

commerce régional solide ainsi que des temps de transit et des frais d’expédition compétitifs. La province<br />

est branchée par une autoroute principale, un corridor multimodal qui encourage la croissance du<br />

commerce domestique et international. La Saskatchewan offre aussi l’accès à une main d’œuvre très<br />

productive et des entreprises du savoir avancées en génie du transport et dans les technologies de<br />

l’information (TI).<br />

Ces attributs, en plus de la disponibilité vaste de terrain et d’infrastructure à des prix modiques, ainsi qu’un<br />

climat d’investissement et d’affaires solide, font ensemble de la Saskatchewan un lieu de choix pour<br />

l’établissement d’un port intérieur le long d’un corridor intégré en Amérique du Nord.<br />

Autoroutes – La Saskatchewan est accessible par l’autoroute Yellowhead et l’autoroute transcanadienne<br />

n° 1, et se branche de façon centrale au corridor de transport CANAMEX et à l’autoroute de l’ALENA qui<br />

rejoint le Canada, les États-Unis et le Mexique.<br />

Chemin de fer – Les voies principales du Canadien National (CN) et du Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique<br />

(CFPC) offrent un service de chemin de fer à deux niveaux, reliant ainsi la province à Vancouver, Toronto,<br />

Montréal, Chicago et à d’autres zones de consommation clé aux États-Unis. La Saskatchewan est le<br />

terminus canadien du chemin de fer CFPC/Soo Line, qui sert de corridor direct vers Chicago et la région du<br />

nord-est des États- Unis. De plus, la ligne ferroviaire sur courte distance de OmniTRAX offre un accès<br />

direct de la Saskatchewan au port de Churchill, et fournit un accès efficace à toutes les destinations nordaméricaines<br />

à travers le système de chemin de fer CN.<br />

Commerce – Le total de commerce mondial en Saskatchewan a augmenté de 102 pourcent au cours des<br />

dix dernières années. Depuis 2005, la Saskatchewan a fait l’expérience d’une augmentation de 13,8<br />

pourcent en exportation internationale et d’une augmentation de 8,2 pourcent en livraison manufacturière<br />

(Bureau des statistiques de la Saskatchewan).<br />

• La Saskatchewan est responsable actuellement pour près du tiers de l’énergie produite au Canada.<br />

• La Saskatchewan est le plus grand producteur de potasse au monde, et produit près la moitié de la<br />

demande sur le plan mondial.<br />

• La Saskatchewan produit 30 pourcent de la production totale d’uranium au monde, et est la seule<br />

région du Canada à produire de l’uranium.<br />

• Le Canada est le plus grand exportateur de lentilles au monde, et la Saskatchewan produit 95 pourcent<br />

de la production totale au Canada.<br />

Main d’oeuvre – La main d’œuvre de la province compte parmi les meilleures éduquées du pays ; environ<br />

60 pourcent de la province a suivi une formation post-secondaire. Les taux salariaux sont aussi plus<br />

concurrentiels que ceux de la Colombie-Britannique et de l’Alberta.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 2

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Technologie – Au cours des dix dernières années, la Saskatchewan a établi des partenariats avec des<br />

experts de l’industrie et d’autres entreprises pour établir des centres de transfert des technologies<br />

innovatrices en vue d’appuyer la recherche et la commercialisation de nouvelles technologies. La province<br />

sert de centre des opérations et appuie les industries et initiatives technologiques suivantes :<br />

• Deux des entreprises du savoir avancées en génie du transport et dans les technologies de<br />

l’information, International Road Dynamics et la Massload Technologies Corporation.<br />

• Des entreprises de TI et des firmes de recherche et de logistique : Axon Development Corporation,<br />

Clevor Technologies, Integrated Designs, Numa Technologies, et la Technology Management<br />

Corporation, LMS Logistics, Ghost Transportation Services, et le centre des ports à conteneurs Yanke.<br />

• Innovation Place à Saskatoon – un des parcs de recherche les plus grands et les plus avancés de<br />

l’Amérique du Nord en pharmaceutique, bioressources et sur l’environnement.<br />

• Le parc de recherches provincial, Regina Research Park – l’un des parcs de recherche les plus récents<br />

au Canada, dont la spécialisation porte sur l’industrie pétrolière, les technologies de l’information et les<br />

sciences de l’environnement.<br />

• SR Net – un consortium de réseau et une largeur de bande de recherche à très haute puissance,<br />

branchée dans un réseau de distribution informatique fort.<br />

Investissement – En 2005, plus de 7,8 milliards de dollars en nouveaux investissements capitaux ont été<br />

investis dans des projets en Saskatchewan, une augmentation de 4,6 pourcent du total en 2004. Plus de<br />

75 pourcent de cet investissement provenait du secteur privé en vue d’agrandir, moderniser et construire<br />

de nouvelles installations dans la province.<br />

Taxes d’affaires – En avril 2006, le gouvernement de la Saskatchewan a donné son approbation pour les<br />

plus grandes coupures aux taxes d’affaires dans l’histoire de la province, rendant ainsi la Saskatchewan<br />

l’une des juridictions les plus concurrentielles au Canada.<br />

Avantage concurrentiel - En 2006, KPMG, une firme de consultation, a publié un rapport qui compare le<br />

coût de faire affaire dans 128 villes de neuf pays en fonction du coût des intrants pour la main d’œuvre, la<br />

taxation, les installations (terrain, construction, coûts de location). Parmi les villes canadiennes étudiées,<br />

les quatre villes de la Saskatchewan (Saskatoon, Regina, Prince Albert et Moose Jaw) se plaçaient audessus<br />

de l’indice canadien et en meilleure position que Calgary, Winnipeg et Kamloops. Saskatoon a<br />

aussi été classé comme juridiction la moins coûteuse parmi les 21 villes en question du Midwest de<br />

l’Amérique du Nord (KPMG 2005)<br />

La réalisation du projet<br />

Le développement et la promotion d’un réseau de port intérieur intelligent au centre de la Saskatchewan et<br />

un <strong>Super</strong> corridor intelligent du Canada (CISCOR), y compris des activités de chaîne d’approvisionnement<br />

basés à l’intérieur, loin des zones actuelles de congestion, assureront que le Canada ait l’infrastructure<br />

nécessaire en place pour améliorer la compétitivité et tirer avantage des opportunités croissantes du<br />

marché mondial.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 3

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Le Réseau de port intérieur intelligent CISCOR en Saskatchewan servirait de plaque tournante de<br />

coordination centrale, joignant le corridor est-ouest canadien (CISCOR) avec le grand corridor nord-sud<br />

nord-américain (NASCO), le corridor entre le Canada et le Mexique (CANAMEX) et la River of Trade<br />

<strong>Corridor</strong> Coalition (ROTCC). Le port intérieur servirait de port intelligent, fournirait des services physiques<br />

de port intérieur et irait se joindre avec et fournirait de l’appui intelligent à des installations de chargement<br />

des conteneurs à travers le réseau nord-américain.<br />

Comme port intelligent, des services de gestion de chaînes d’approvisionnement à valeur ajoutée<br />

assureraient que les cargaisons soient acheminées efficacement, économiquement et à temps, en fonction<br />

de la stratégie de entre le Canada et les Etats-Unis serait atteint grâce à l’intégration de services<br />

d’informations et de sécurité à la fine pointe de la technologie pour l’échange de données de transport et<br />

d’échange.<br />

Il est recommandé que le Réseau de port intérieur intelligent CISCOR, qui offre et coordonne les services<br />

et installations suivants :<br />

• les zones de libre échange ;<br />

• les entrepôts de distribution ;<br />

• le dédouanement ;<br />

• les opérations de transbordement ;<br />

• la gestion de conteneurs vides ; et<br />

• un centre de logistique avancée qui emploie des systèmes d’informations d’échange à la fine pointe de<br />

la technologie.<br />

Avantages<br />

Ce complexe de port intérieur sera avantageux pour les transporteurs ferroviaires commerciaux et les<br />

lignes d’expédition, les ports nationaux et le personnel des ports privés, d’autres installations de<br />

chargement, les propriétaires des cargaisons (d’importation ou d’exportation), ainsi que tous les niveaux du<br />

gouvernement du Canada. Ces avantages dépendent de la création d’une plaque tournante de port<br />

intérieur intelligent qui répondrait aux besoins de tous les intervenants et développerait une base<br />

d’expédition suffisamment grande pour soutenir une masse critique d’opération. Le volume de cargaison<br />

est la clé de la viabilité d’un port intérieur, son élément d’attrait pour les intervenants et ses avantages<br />

potentiels en termes de coût, d’efficacité, d’accessibilité, de service et de fiabilité.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 4

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Transporteurs ferroviaires<br />

• Attrait potentiel d’au moins 130 000 EVP par année de cargaisons importées de l’Asie qui recherchent<br />

des routes alternatives vers le cœur de l’Amérique du Nord, un chiffre qui augmentera avec le temps.<br />

• Attrait potentiel d’au moins 130 000 EVP par année de cargaisons d’exportation recherchant des<br />

routes surtout vers les marchés de l’Asie Pacifique, un chiffre qui augmentera avec le temps.<br />

• La capacité de remplir des contenants destinés à être expédiés vers l’Ouest et des wagons<br />

multimodaux destinés à être expédiés vers l’Ouest avec une cargaison à revenu qui ne serait pas<br />

autrement retournée, augmentant ainsi la capacité en raison d’une meilleure utilisation des actifs et<br />

d’un nombre réduit de déplacements non productifs.<br />

• Un service plus fréquent et à l’heure pour les clients à courte distance, les destinations à faible taux de<br />

volume, et les destinations américaines à l’ouest des plaques tournantes du chemin de fer américain,<br />

ainsi que des nouveaux services aux clients locaux, de l’ALENA et internationaux.<br />

Lignes d’expédition<br />

• Le dédouanement automatisé pour réduire les arrêts temporisés et permettre les passages spéciaux à<br />

haute vitesse à la frontière.<br />

• Des services consolidés de données à valeur ajoutée et un cadre de professionnels de gestion de<br />

données à l’intérieur d’une seule plaque tournante de logistique d’information pour servir le <strong>Super</strong><br />

corridor intelligent du Canada.<br />

• Attirer des cargaisons de cargaisons de retour à revenu, à l’aide d’une gestion intelligente du<br />

déploiement et du positionnement de conteneurs vides.<br />

<strong>Port</strong>s<br />

• Un service de livraison plus rapide pour les conteneurs, qui seront entreposés, classés ou transbordés<br />

en Saskatchewan. Cela aidera à augmenter de débit des installations de port de mer existantes.<br />

• Recouvrement de terrain de port de mer critique pour l’offre de fonctions de port essentielles et pour<br />

réduire le besoin d’infrastructure locale additionnelle.<br />

• Avantage compétitif envers les ports américains rivaux grâce à une gestion efficace du transport<br />

terrestre, contribuant ainsi à augmenter davantage la concentration de cargaisons.<br />

Expéditeurs<br />

• Une source abordable de chargement de produits d’exportation, contrairement à la conteneurisation au<br />

port.<br />

• Produits d’exportation nécessitant une « préservation de l’identité » qui peut être obtenue par<br />

l’emballage ou la mise en conteneur en Saskatchewan sans mélange de produits d’origine d’ailleurs.<br />

• De meilleures options de logistique augmentant l’efficacité et la productivité des actifs existants<br />

d’infrastructure de chemin de fer.<br />

Le gouvernement canadien et la Province de la Saskatchewan<br />

• La croissance et le développement d’occasions d’affaires sur le plan local, incités par la présence d’un<br />

centre de cargaisons à proximité, y compris l’entreposage et la distribution commerciales, les services<br />

de maintien des équipements, les services de transport et des services de logistique auxiliaires.<br />

• La diversification de l’économie vers d’autres secteurs industriels en vue d’éviter les baisses cycliques<br />

qui ont lieu dans la plupart des secteurs industriels menés par les produits de base.<br />

• Une augmentation des revenus d’impôts en raison de nouveaux reçus d’affaires et de paie.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 5

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Évaluation du marché<br />

La viabilité des installations de port intérieur intelligent proposées pour la Saskatchewan dépend, en partie<br />

du volume de chargements qui y passeraient. La demande pour un système de port intérieur coordonné<br />

en Saskatchewan viendrait d’abord des marchés multimodaux du Canada et des Etats-Unis. Une des<br />

difficultés de l’estimation du trafic potentiel est que le montant de trafic dépend des taux et des niveaux de<br />

service, éléments inconnus chez de nouvelles installations. Pour identifier le flux de chargements vers et<br />

en provenance des provinces contenant des ports importants (Colombie-Britannique, Québec, etc.) Selon<br />

les statistiques d’échange, les connaissances de l’industrie et d’autres analyses quantitatives, il a été<br />

déterminé que l’analyse devrait se concentrer sur le marché trans-Pacifique et sur le marché de l’ALENA<br />

car celles-ci présenteraient les meilleures opportunités, à la fois de la perspective du volume et de la<br />

croissance future.<br />

Tableau SE-1 : Sommaire de la conteneurisation future de l’exportation de la Saskatchewan vers l’Asie (données de<br />

2004-2005)<br />

Tonnes Part EVP EVP<br />

Exportation de produits agricoles de base 4 865 369 29 % 69 373<br />

Exportation de produits agricoles traités 512 979 100 % 29 020<br />

Exportation de potasse 3 147 870 5 % 9 258<br />

Exportation de pâtes et papier 108 639 50 % 2 173<br />

Total des exportations dans l’analyse 8 634 856 25 % 109 824<br />

Tableau SE-2 : Sommaire de la conteneurisation future de l’exportation de la Saskatchewan vers l’ALENA (données de<br />

2004-2005)<br />

Tonnes Part EVP EVP<br />

Exportation de produits agricoles de base 1 325 724 18 % 11 877<br />

Exportation de produits agricoles traités 754 927 100 % 45 783<br />

Exportation de potasse 5 437 230 5 % 15 992<br />

Exportation de pâtes et papiers 286 411 25 % 2 864<br />

Exportation totale dans l’analyse 7 804 293 20 % 76 516<br />

Tableau SE-3: Marché potentiel du réseau de port intérieur intelligent CISCOR<br />

EVP EVP – 30 % EVP + 10 %<br />

Vers l’Asie 109 824 76 877 120 807<br />

De l’Asie 1 109 824 76 877 120 807<br />

Vers l’ALENA 76 516 53 561 84 168<br />

De l’ALENA 1 76 516 53 561 84 168<br />

Débit total 372 681 260 877 409 949<br />

(1) Tient pour acquis que les lignes d’expédition chercheront à maintenir un débit balancé, où chaque chargement d’exportation<br />

sera équilibré avec un chargement d’importation.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 6

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Il est raisonnable d’assumer que les lignes d’expédition du port intérieur auraient au minimum un débit<br />

équilibré, c’est-à-dire qu’un conteneur arrêté au port intérieur doit arrimer un chargement d’exportation.<br />

Dans ce cas, la taille estimée du marché annuel vers l’intérieur se chiffrerait vers 130 000 à 205 000 EVP<br />

selon les estimés des exportations actuellement disponibles dont l’origine est la Saskatchewan. En se<br />

basant sur cette approche, le port intérieur aurait un débit total de 260 000 à 410 000 EVP par année, ce<br />

qui comprend des importations et exportations asiatiques et des importations et exportations nordaméricaines.<br />

Un facteur qui risque d’encourager les lignes d’expédition à arrêter les conteneurs destinées vers l’intérieur<br />

au port intérieur serait la capacité de retourner rapidement les conteneurs vides vers l’Asie pour des<br />

chargements d’importation à plus grand revenu. De plus, la capacité de transbordement des produits<br />

d’exportation de partout au Canada et du coin nord-est des États-Unis avec des capacités intelligentes<br />

pour le dédouanement est un avantage de plus. Ainsi, le potentiel total de débit pourrait dépasser 500 000<br />

EVP, en tenant pour acquis que le coût, le transport et les conditions de service soient en place pour faire<br />

du port intérieur intelligent une installation viable de distribution, de transbordement et de dédouanement<br />

pour les expéditeurs, les lignes de transport et les chemins de fer.<br />

Selon l’expérience du port intelligent de Kansas City, inclure une zone de libre échange près des<br />

installations de port intérieur pourrait créer un nouveau centre compétitif de fabrication, de distribution et<br />

d’échange, ce qui améliorera les produits composants destinés pour l’intérieur et les produits fabriqués<br />

destinés vers l’extérieur (exportés à nouveau).<br />

Analyse de coût<br />

Un des aspects importants dans la détermination de la faisabilité d’un système coordonné de port intérieur<br />

en Saskatchewan consiste à évaluer si le port serait compétitif avec les options existantes de transport.<br />

Une connexion multimodale vers le Midwest, surtout Chicago, représenterait l’une des meilleures<br />

opportunités pour un port intérieur CISCOR proposé. Cette analyse de coût examinerait les coûts actuels<br />

de transport par camion et par chemin de fer entre le <strong>Port</strong> de Vancouver et Chicago. Ces coûts sont<br />

comparés aux coûts estimés pour le transport de marchandises via le port intérieur en Saskatchewan.<br />

Le Tableau SE-4 démontre que l’utilisation d’un port intérieur impose un coût supplémentaire de 400 $ pour<br />

le transbordement pour chaque conteneur de 40 pieds. Cependant, ces estimés simplifiés ne considèrent<br />

pas le potentiel de recouvrir ces coûts à d’autres endroits dans la chaîne d’alimentation, tels que dans la<br />

réduction de déplacements sans revenu en chargeant les conteneurs vides avec des marchandises<br />

locales, une meilleure gestion de l’inventaire ou un prix compétitif pour l’envoi de nombres considérables<br />

de conteneurs à destination et en provenance du port intérieur.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 7

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Tableau SE-4. Comparaison des coûts estimés d’un conteneur international en transbordement dans un port intelligent<br />

versus la livraison directe.<br />

Dollars canadiens Vancouver -<br />

Saskatchewan<br />

Vancouver -<br />

Saskatchewan<br />

Vancouver –<br />

Chicago<br />

- Chicago<br />

- Chicago<br />

Mode de transport Chemin de fer Chemin de fer et Chemin de fer<br />

camion<br />

Coût par conteneur de 40 pieds 1<br />

Chemin de fer multimodal 1 400 $ 1 400 $ 2 200 $<br />

Coûts de levage/charrette 50 $ 50 $<br />

Transbordement intérieur 350 $ 350 $<br />

Coûts de levage/charrette 50 $ -<br />

Chemin de fer multimodal 2 800 $ -<br />

Camion 3 - 1 000 $<br />

Charrette de destination 4 120 $ - 175 $<br />

Coût total par conteneur de 40 2 770 $ 2 800 $ 2 375 $<br />

pieds<br />

(1) Les taux ne comprennent pas le supplément carburant.<br />

(2) Tient pour acquis le transbordement de trois conteneurs de 40 pieds vers deux conteneurs domestiques ; le taux par<br />

conteneur domestique est de 1 200 $ chacun.<br />

(3) Tient pour acquis le transbordement de trois conteneurs de 40 pieds vers deux remorques domestiques ; le taux par<br />

remorque domestique est de 1 500 $ chacune.<br />

(4) Tient pour acquis le transbordement de trois conteneurs de 40 pieds vers deux conteneurs domestiques, et un taux de<br />

charrette sur place de 175 $.<br />

L’analyse tient aussi compte de l’épargne dans la conteneurisation des produits en vrac pour exportation<br />

au port intérieur. La tendance mondiale favorisant la conteneurisation des produits de base en vrac reflète<br />

l’établissement d’un équilibre entre les taux d’expédition en vrac et par conteneur, les temps plus courts<br />

pour la livraison multimodale, et un plus grand souci de la qualité du produit et de la sécurité de la<br />

cargaison. Le tableau SE-5 indique que le chargement à la source des conteneurs a un coût inférieur<br />

l’expédition de produits par wagon-trémie au port suivi du transbordement dans des conteneurs au port.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 8

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Tableau SE-5 : Analyse des coûts de transport pour expéditeurs<br />

Source chargée aux<br />

points en Saskatchewan<br />

Chargé au port, origine<br />

en Saskatchewan<br />

Charrette d’origine 430 $ -<br />

Chemin de<br />

fer/wagontrémie<br />

- 3 550 $<br />

Chemin de<br />

fer/conteneur<br />

1 100 $* 890 $**<br />

Charrette de<br />

destination<br />

- 230 $<br />

Empotage - 545 $<br />

Total par<br />

contenant<br />

1 530 $ 1 665 $<br />

Différence - +9 %<br />

*Basé sur 90 MT par wagon-trémie, l’équivalent de quatre conteneurs de 20 pieds à 22,5 MT par conteneur.<br />

** Taux équivalent par contenant basé sur quatre chargements de conteneur par wagon-trémie.<br />

Source : « Container Measures Study: Issues and Discussion for Proposed Measures for the Grain<br />

Monitoring Program » Juin 2006, Gouvernement du Canada<br />

Conclusion<br />

L’étude a identifié une occasion viable de développer des installations de port intérieur intelligent en<br />

Saskatchewan, à condition que certaines conditions critiques soient présentées :<br />

• Une masse critique de cargaisons, à la fois des importations destinées vers l’intérieur pour la<br />

distribution, et des exportations destinées vers l’extérieur, doit être développée en Saskatchewan.<br />

Cela comprend le transbordement et la distribution de produits importés pour le marché nordaméricain,<br />

ainsi que le chargement des conteneurs vides avec des produits locaux et transbordés<br />

destinés à l’exportation.<br />

• Un volume suffisant de wagons de chemin de fer doit être présent au port intérieur intelligent pour<br />

justifier des trains spécialisés à destination et en provenance de la côte nord-ouest du Pacifique.<br />

• Le port intérieur doit offrir des services de logistiques attrayants, à valeur ajoutée pour motiver la<br />

communauté d’expédition et créer un avantage compétitif intelligent distinct en comparaison avec les<br />

modes conventionnels de distribution de cargaisons.<br />

• L’économie du port intérieur doit être attrayant pour les intérêts des opérateurs, des investisseurs et de<br />

l’expédition.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 9

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Lorsqu’on aura répondu à ces critères, le port intérieur de la Saskatchewan deviendra une partie viable du<br />

réseau multimodal et engendrera des avantages compétitifs importants :<br />

• Développement d’un portail national viable et sécuritaire, compétitif et à la fine pointe de la technologie.<br />

• Amélioration et exécution du pont terrestre multimodal naissant au Canada (<strong>Super</strong> corridor intelligent<br />

canadien, ou CISCOR).<br />

• Intégration de services de technologies de l’information avant-gardiste pour les fournisseurs de<br />

transport en vue d’atteindre l’excellence en chaîne d’approvisionnement, et permettant un contrôle<br />

maximal des cargaisons de bout en bout.<br />

• Création de zones de libre-échange pour attirer les fabricants pour la réexportation.<br />

• Stimulation d’occasions d’importation et d’exportation asiatiques additionnelles pour le Canada et le<br />

nord-ouest des États-Unis.<br />

• Établissement d’échange par la consolidation et la conteneurisation de cargaisons d’importation et<br />

d’exportation à des centres d’entreposage et de logistique au port intérieur.<br />

• Établissement d’installations terminales incultes, « prêtes pour l’avenir », qui intègrent des<br />

équipements à la fine pointe de la technologie et les avances technologiques prêts à réagir aux défis<br />

de port et multimodaux d’aujourd’hui et de demain.<br />

Pour réaliser la promesse de l’initiative de développement d’un port intérieur en Saskatchewan servant de<br />

noyau au <strong>Super</strong> corridor intelligent du Canada, les étapes de faisabilité suivantes devraient être<br />

entreprises :<br />

• Commencer une réforme législative ;<br />

• Effectuer une analyse en détail du marché et une étude de développement ;<br />

• Vérifier les coûts de l’équipement et de la construction capitale ;<br />

• Quantifier les coûts d’opération et les retours prévus ;<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 10

Executive Summary<br />

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Global merchandise exports and imports exceeded the $10 trillion mark in 2005-06. A majority of the<br />

new containerships entering the world fleet in the next five years will be post-Panamax vessels<br />

ready to transport cargo from China, Southeast Asia and India to North American ports already<br />

strained by capacity limits. The Panama Canal is approaching operational capacity and the U.S.<br />

transportation network is struggling to meet the predicted 15 percent annual rise in Asian container traffic.<br />

In response to the rapid growth in North American trade, the shift in the global freight supply chain, and the<br />

increased congestion at U.S. ports and along the intermodal system, shippers are now routing a growing<br />

share of cargo via <strong>Canadian</strong> ports.<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> Solution<br />

As the first North American port of call on the trans-Pacific route from Asia and the trans-Atlantic route from<br />

Europe, Canada has an opportunity to develop a sophisticated intermodal distribution network to serve the<br />

growing U.S. Midwest and <strong>Canadian</strong> consumption zones. Canada can serve as the North American<br />

gateway at the intersection of three powerful and shifting trade networks—the north-south North American<br />

Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the European-NAFTA, and the highly-utilized trans-Pacific route. The<br />

desired result is a fully-integrated, seamless cargo transport corridor moving cargo from the ports to rail and<br />

highways and to an inland port logistics centre that serves all North American markets.<br />

Since the Vancouver and Prince Rupert ports are located on the West Coast of Canada, and Halifax, Strait<br />

of Canso and Montreal ports are on the East Coast, there are distinct advantages in promoting the<br />

development of an integrated national intermodal strategy for Canada as a nation. This emerging<br />

transcontinental land bridge and a central smart inland port to serve <strong>Canadian</strong> and U.S. markets from<br />

Pacific to Atlantic oceans would benefit the ports involved, the rail and shipping lines, the large retailers and<br />

the nation.<br />

Figure ES-1. <strong>Canadian</strong> Intermodal <strong>Network</strong><br />

Source: TranSystems, Railway Association of Canada<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 11

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

The Prairie Region – The Saskatchewan Advantage<br />

Saskatchewan is the transportation crossroads of the northern half of the North American continent with<br />

linkages to the four points of the compass. Its optimal location and central access to the freight logistics<br />

network makes Saskatchewan an ideal site for a thriving inland cargo gateway complex away from<br />

congestion points.<br />

The province’s geographic proximity to North American population centres, within two days travel from 80<br />

million people in Canada and the U.S., is further supported by strong regional trade and competitive transit<br />

times and shipping rates. The province is connected by a principal highway and intermodal corridor that<br />

supports growth in domestic and international trade. Saskatchewan also offers access to a highly<br />

productive labour market and advanced intelligent transportation engineering and information technology<br />

(IT) companies.<br />

These features, together with broad availability of land and infrastructure at advantageous cost, and a<br />

strong investment and business climate, combine to confirm that Saskatchewan is the location of choice for<br />

an inland port along an integrated North American corridor.<br />

Highways - Saskatchewan is accessed by the Yellowhead Highway and Trans-Canada Highway #1 and is<br />

centrally linked to the CANAMEX transportation corridor and NAFTA <strong>Super</strong>highway connecting Canada,<br />

the U.S. and Mexico.<br />

Rail - <strong>Canadian</strong> National (CN), <strong>Canadian</strong> Pacific Railroad (CPR) main lines run double-stack rail service<br />

through Saskatchewan, linking the province to Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, Chicago and other key<br />

consumption zones in the U.S. Saskatchewan is the <strong>Canadian</strong> terminus of the CPR/Soo Line, which is a<br />

direct corridor to Chicago and the U.S. northeast. In addition, the OmniTRAX short line provides direct<br />

access to the <strong>Port</strong> of Churchill from Saskatchewan, and provides efficient access to all North American<br />

points through the CN railway system.<br />

Trade - Total world trade from Saskatchewan has risen by 102 percent over the last decade. In 2005,<br />

Saskatchewan experienced a 13.8 percent increase in international exports and an 8.2 percent increase in<br />

manufacturing shipments (Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics).<br />

• Saskatchewan currently accounts for nearly one-third of the energy produced in Canada.<br />

• Saskatchewan is the largest producer of potash in the world, providing nearly one-half of the total<br />

global demand.<br />

• Saskatchewan supplies 30 percent of the world’s output of uranium and is the only jurisdiction that<br />

produces uranium in Canada.<br />

• Canada is the largest lentil exporter in the world, and Saskatchewan produces 95 percent of Canada’s<br />

total production.<br />

Labour force –The province’s workforce is one of the best educated in the country with approximately 60<br />

percent of employees having some post-secondary education. Wage rates are also more competitive than<br />

British Columbia and Alberta.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 12

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Technology – In the past decade, Saskatchewan has partnered with industry experts and other<br />

enterprises to establish innovative technology transfer centres to assist in research and the<br />

commercialization of new technology. The province serves as the centre of operations and supports the<br />

following technological industries and initiatives:<br />

• Two of the most successful intelligent systems transportation engineering, IT and design companies in<br />

Canada - International Road Dynamics and Massload Technologies Corporation.<br />

• IT companies and research and logistics firms - Axon Development Corporation, Clevor Technologies,<br />

Integrated Designs, Numa Technologies, and Technology Management Corporation, LMS Logistics,<br />

Ghost Transportation Services, and Yanke Container <strong>Port</strong> Centre.<br />

• Innovation Place in Saskatoon - one of North America’s largest and most advanced research parks for<br />

pharmaceuticals, bio-resources, and the environment.<br />

• The Regina Research Park - one of Canada’s newest research parks specializing in petroleum,<br />

information technology and environmental sciences.<br />

• SR Net - an extremely high-powered research bandwidth and networking consortium, plugged into a<br />

powerful distributed grid computing network.<br />

Investment - In 2005, over $7.8 billion in new capital investment poured into Saskatchewan projects, up by<br />

4.6 percent from the level in 2004. More than 75 percent of that investment came from the private sector to<br />

expand, modernize and build new facilities in the province.<br />

Business taxes - In April 2006, the Government of Saskatchewan approved the largest business tax cuts<br />

in the province’s history, making Saskatchewan one of the most tax-competitive jurisdictions in Canada.<br />

Competitive advantage - In 2006, the international consulting firm KPMG released a report that compares<br />

the cost of doing business in 128 cities in nine countries based on input costs for labour, taxation, facilities<br />

(land, construction, leasing rates), transportation, utilities, depreciation, and financing (interest costs).<br />

Among the <strong>Canadian</strong> cities studied in the report, the four Saskatchewan cities (Saskatoon, Regina, Prince<br />

Albert and Moose Jaw) rated better than the <strong>Canadian</strong> index and ahead of Calgary, Winnipeg and<br />

Kamloops. Saskatoon was also ranked the lowest-cost jurisdiction among the 21 featured cities from the<br />

North American Midwest (KPMG 2005)<br />

Bringing It All Together<br />

The development and promotion of a <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong> in central Saskatchewan and associated<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> (CISCOR) - including a more efficient inland-based supply chain<br />

activity away from current congestion points - will ensure that Canada has the necessary infrastructure in<br />

place to improve competitiveness and take advantage of the growing opportunities in world trade.<br />

The CISCOR <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong> in Saskatchewan would serve as the central coordination hub,<br />

connecting the <strong>Canadian</strong> east-west corridor (CISCOR) with the major North American north-south corridor<br />

– the North America <strong>Super</strong><strong>Corridor</strong> (NASCO), the Canada Mexico <strong>Corridor</strong> (CANAMEX) and the River of<br />

Trade <strong>Corridor</strong> Coalition (ROTCC). The inland port would function as an intelligent “smart port”, provide<br />

physical inland port functions and connect with and provide intelligent support to container loading facilities<br />

throughout the North American network.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 13

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

As a “smart port”, value-added supply chain management services would ensure that shipments are<br />

executed efficiently, economically, on time, and according to each customer’s logistics strategy. The<br />

seamless and timely clearance of international shipments between Canada and the U.S. would be<br />

achieved through the integration of leading-edge information and security technology services for the<br />

exchange of transportation and trade data.<br />

It is recommended that the CISCOR <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong> offer and coordinate the following services<br />

and facilities:<br />

• free trade zones,<br />

• distribution warehouses,<br />

• customs clearance,<br />

• transload operations,<br />

• empty container management and<br />

• advanced logistics centre employing state-of-the-art trade information systems.<br />

Benefits<br />

This inland port complex will benefit the commercial rail carriers and shipping lines, the national ports and<br />

private port operators, other loading facilities across the CISCOR network, the cargo owners (both import<br />

and export) plus all levels of government within Canada. These benefits are contingent on creating a smart<br />

inland port hub that would fulfill the needs of all of the stakeholders and develop a large enough cargo base<br />

to sustain a critical mass of operation. Shipment volume is the key to the viability of an inland port, its<br />

attractiveness to the stakeholders and its potential benefits in cost, efficiency, accessibility, service and<br />

reliability.<br />

Rail carriers<br />

• Potential capture of at least 130,000 TEU per year of import cargo from Asia that are seeking<br />

alternative routes into the heartland of North America, which will increase over time.<br />

• Potential capture of at least 130,000 TEU per year of export cargo that is seeking routes primarily to<br />

the Asia Pacific markets, which will increase over time.<br />

• The ability to fill westbound containers and westbound intermodal cars with revenue cargo that would<br />

otherwise be returned empty, thereby increasing capacity due to better asset utilization and fewer nonproductive<br />

moves.<br />

• More frequent and timely service for short-haul customers, low-volume destinations and U.S.<br />

destinations west of the existing U.S. rail hubs, as well as new services to local, NAFTA and<br />

international customers.<br />

Shipping lines<br />

• Automated customs clearance to reduce cargo dwell and allow high-speed “blue lane” border<br />

crossings.<br />

• Consolidated value-added data services and a cadre of supply chain data management professionals<br />

into a single logistics information hub to serve the <strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong>.<br />

• Attract backhaul revenue cargo through the intelligent management of empty container deployment and<br />

positioning.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 14

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

<strong>Port</strong>s<br />

• Faster cargo velocity for containers, which will to be stored, sorted or transloaded in Saskatchewan.<br />

This will help increase the throughput of existing seaport facilities.<br />

• Recovery of vital seaport land areas to serve essential port functions and reduce the need for<br />

additional local infrastructure.<br />

• Competitive advantage over rival U.S. ports through effective landside-transportation management,<br />

further boosting cargo concentration.<br />

Shippers<br />

• Cost-effective source loading of export products as opposed to containerizing at the port.<br />

• Export products requiring “identity preservation” that is attained by packaging or containerizing in<br />

Saskatchewan without admixture of products originating elsewhere.<br />

• Enhanced logistics options that increase efficiency and productivity of existing rail infrastructure assets.<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> Government and Province of Saskatchewan<br />

• Growth and development of local business opportunities brought on by the presence of a nearby cargo<br />

centre including commercial warehousing and distribution, equipment maintenance services, haulage<br />

services and ancillary logistics services.<br />

• Diversification of the economy into other industries in order to avoid the cyclic downturns that occur in<br />

most commodity driven industries.<br />

• Increased local tax revenues due to new payroll and business receipts.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 15

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Market Assessment<br />

The viability of smart inland port facilities proposed for Saskatchewan is dependent, in part, on the volume<br />

of freight which it would attract. Demand for a coordinated inland port system in Saskatchewan would<br />

primarily originate from <strong>Canadian</strong> and U.S. intermodal markets. One difficulty in estimating potential traffic<br />

is that the amount of traffic depends on rates and service levels, and these are unknown for a new facility.<br />

In order to identify flows between the Saskatchewan region and other global partners, it was necessary to<br />

study freight flows to and from provinces that contain major ports (British Columbia, Quebec, etc.). Based<br />

on trade statistics, industry knowledge and other quantitative analyses, it was determined that the analysis<br />

should focus on the trans-Pacific and NAFTA market as these lanes present the greatest opportunity, from<br />

both a volume and future growth perspective.<br />

Table ES-1: Summary of Future Containerization of Saskatchewan Exports to Asia (2004-2005 Data)<br />

Tonnes TEU Share TEU<br />

Ag Commodity Exports 4,865,369 29% 69,373<br />

Ag Processed Exports 512,979 100% 29,020<br />

Potash Exports 3,147,870 5% 9,258<br />

Pulp Exports 108,639 50% 2,173<br />

Total Exports in Analysis 8,634,856 25% 109,824<br />

Table ES-2: Summary of Future Containerization of Saskatchewan Exports to NAFTA (2004-2005 Data)<br />

Tonnes TEU Share TEU<br />

Ag Commodity Exports 1,325,724 18% 11,877<br />

Ag Processed Exports 754,927 100% 45,783<br />

Potash Exports 5,437,230 5% 15,992<br />

Pulp Exports 286,411 25% 2,864<br />

Total Exports in Analysis 7,804,293 20% 76,516<br />

Table ES-3: Potential CISCOR <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong> Market<br />

TEU TEU - 30% TEU + 10%<br />

Asia Outbound 109,824 76,877 120,807<br />

Asia Inbound 1 109,824 76,877 120,807<br />

NAFTA Outbound 76,516 53,561 84,168<br />

NAFTA Inbound 1 76,516 53,561 84,168<br />

Total Throughput 372,681 260,877 409,949<br />

(1) Assumes shipping lines will seek to maintain a balanced flow with each export load offset by an import load.<br />

A reasonable floor for the potential throughput of the inland port is the assumption that the shipping lines<br />

would seek to have a balanced flow – that is, a container stopped at the inland port must secure an export<br />

load. In this case, the estimated annual inbound market size is around 130,000 to 205,000 TEUs based on<br />

estimates of currently available exports originating in Saskatchewan. Based on this approach the inland<br />

port would have a total throughput of 260,000 to 410,000 TEUs per year, comprising Asian imports and<br />

exports and North American imports and exports.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 16

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

A factor that may encourage shipping lines to stop inbound containers at the inland port would be the ability<br />

to rapidly return empty containers to Asia for high revenue import loads. A further benefit is the ability to<br />

transload export-oriented products from across Canada and the north-east U.S. with intelligent capabilities<br />

for customs clearance. Therefore, the total potential throughput could be over 500,000 TEUs assuming<br />

the cost, transit and service conditions are in place to make the smart inland port viable distribution,<br />

transloading facility and customs clearance for the shippers, shipping lines, and railroads.<br />

Based on the experience of Kansas City <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Port</strong>, including a free trade zone near the inland port<br />

facilities may create a competitive new manufacturing, distribution and trading centre, which will enhance<br />

inbound component products and outbound (re-exported) manufactured goods.<br />

Cost Analysis<br />

An important aspect of determining the feasibility of a coordinated inland port system in Saskatchewan is<br />

evaluating whether the port would be competitive with existing transportation options. An intermodal<br />

connection to the Midwest, specifically Chicago, would represent one of the best opportunities for a<br />

proposed CISCOR inland port. This cost analysis examines the current trucking and rail costs between the<br />

<strong>Port</strong> of Vancouver and Chicago. These costs are compared with the estimated costs for transporting goods<br />

through the inland port in Saskatchewan.<br />

Table ES-4 reveals that an additional $400 associated with transload costs is incurred per 40-foot container<br />

by using an inland port. However, these simplified estimates do not account for the potential to recover<br />

costs elsewhere in the supply chain, such as reduced non-revenue moves by loading empty containers with<br />

local cargo, better management of inventory or competitive pricing for volume container shipments moving<br />

to and from the inland port.<br />

Table ES-4. Estimated Cost Comparison of an International Container Transloaded at <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Port</strong> vs. Direct Shipment<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> Dollars Vancouver -<br />

Saskatchewan<br />

Vancouver -<br />

Saskatchewan<br />

Vancouver –<br />

Chicago<br />

- Chicago<br />

- Chicago<br />

Transport Mode Rail Rail & Truck Rail<br />

Cost per 40-ft Container 1<br />

Intermodal Rail $1,400 $1,400 $2,200<br />

Lift / Dray Cost $50 $50<br />

<strong>Inland</strong> Transload $350 $350<br />

Lift / Dray Cost $50 -<br />

Intermodal Rail 2 $800 -<br />

Truck 3 - $1,000<br />

Destination Local Dray 4 $120 - $175<br />

Total Cost per 40-ft Container $2,770 $2,800 $2,375<br />

(5) Rates exclude fuel surcharges<br />

(6) Assumes three 40-ft containers transloaded to two domestic containers and rate per domestic container is $1,200.<br />

(7) Assumes three 40-ft containers transloaded to two domestic trailers and rate per domestic trailer is $1,500.<br />

(8) Assumes three 40-ft containers transloaded to two domestic containers and local dray rate is $175.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 17

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

The analysis also considered the cost savings in containerizing export bulk products at the inland port. The<br />

global trend towards containerization of bulk commodities reflects the balancing of bulk and container<br />

shipping rates, shorter intermodal delivery times, and increased concerns about product quality and<br />

shipment safety. Table ES-5 indicates that source loading of containers costs less than shipping product by<br />

rail hopper car to the port and then loading into containers at the port.<br />

Table ES-5: Shipper Transport Cost Analysis<br />

Source Loaded at Points<br />

in Saskatchewan<br />

<strong>Port</strong> Loaded, Origin<br />

Saskatchewan<br />

Origin Dray $430 -<br />

Rail / Hopper Car - $3,550<br />

Rail / Container $1,100* $890**<br />

Destination Dray - $230<br />

Stuffing - $545<br />

Total per Container $1,530 $1,665<br />

Difference - +9%<br />

*Based on 90 MT per hopper car, the equivalent of four 20-foot containers at 22.5 MT per container.<br />

** Equivalent rate per container based on four container loads per hopper car.<br />

Source: “Container Measures Study: Issues and Discussion for Proposed Measures for the Grain<br />

Monitoring Program” June 2006, Government of Canada<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 18

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Conclusion<br />

The study identified a viable opportunity to develop smart inland port facilities in Saskatchewan given that<br />

certain critical conditions are met:<br />

• A critical mass of cargo, both inbound imports for distribution and outbound exports, must be<br />

developed in Saskatchewan. This includes transload and distribution of imported products for the<br />

North American market, as well as loading empty containers with local and transloaded products for<br />

export.<br />

• Sufficient rail car volume must take place at the smart inland port to justify dedicated unit trains to and<br />

from the Pacific Northwest.<br />

• The inland port must offer compelling, value-added logistics services to engage the shipping<br />

community and create a distinct intelligent competitive advantage over “business as usual” cargo<br />

distribution modes.<br />

• The economics of the inland port must be attractive to operators, investors and shipping interests.<br />

When these conditions are met, the inland port in Saskatchewan will be a viable part of the <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

intermodal network and will result in significant competitive advantages and benefits:<br />

• Development of a state-of-the art, competitive, secure and sustainable national gateway.<br />

• Enhancement and fulfillment of Canada’s emerging national intermodal land bridge (<strong>Canadian</strong><br />

<strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong>).<br />

• Integration of leading-edge information technology services for transport providers to achieve supply<br />

chain excellence, allowing maximum control of end to-end shipments.<br />

• Creation of free-trade zones to attract manufacturing for re-export.<br />

• Stimulation of additional Asian import and export opportunities for Canada and Northwest U.S.<br />

• Establishment of trade through consolidation and containerization of import and export cargo at<br />

warehousing and logistics centres at the inland port.<br />

• Establishment of unique “greenfield” terminal facilities made “future ready”, integrating state-of-the-art<br />

equipment and technological advancement tailored to meet port and intermodal challenges of today<br />

and tomorrow.<br />

To realize the promise of the initiative to develop an inland port in Saskatchewan that serves as the nucleus<br />

to a <strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong>, the following feasibility steps should be undertaken:<br />

• initiate legislative reform,<br />

• perform detailed market assessment and development study,<br />

• verify the capital construction and equipment costs,<br />

• quantify the operational costs and projected returns, and<br />

• build a comprehensive financial model.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc. E- 19

Introduction<br />

W value in 2005-06 and<br />

exceeded the USD $10 trillion mark.<br />

World and North American<br />

merchandise exports were nearly twice<br />

the gross domestic product (GDP) in<br />

2005 as shown in Figure I-1.<br />

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

orld merchandise trade (exports and imports) grew by 6.5 percent during 2005, according to the<br />

World Trade Organization. Global merchandise exports, as well as imports, rose by 13 percent in<br />

Figure I-1. Growth in Volume of World and North American<br />

Merchandise Trade and GDP, 1995-2005 (annual percentage change)<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

Maritime container traffic has grown to<br />

represent over 85 percent of<br />

4<br />

merchandise cargo shipped worldwide.<br />

2<br />

World container traffic is growing at a<br />

compound rate of over 6.7 percent per 0<br />

year and is expected to double in the<br />

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005<br />

-2<br />

next two decades. The majority of this<br />

increase will be in the trans-Pacific<br />

-4<br />

trade lanes where up to 15 percent<br />

-6 North America Merchandise Exports World Merchandise Exports<br />

compound annual growth is expected<br />

World GDP<br />

North America GDP<br />

through the year 2015. The Panama<br />

Source: World Trade Organization<br />

Canal is presently operating at 85<br />

percent capacity and even with a 2015 expansion will not absorb the predicted rise in Asian traffic.<br />

Therefore, shippers and beneficial cargo owners continue to seek stable and reliable supply chain routes.<br />

North America, Western Europe and Pacific Asia are the dominant global trading regions handling the<br />

majority of worldwide manufacturing and distribution trade. Cargo volumes continue to increase rapidly at<br />

ports in North America, adding more than four million TEUs 1 every year to the current annual volume of 48<br />

million TEUs. This increasing growth in world trade is changing the distribution landscape and putting<br />

pressure on existing North American ports. In the U.S., moving this volume of containers has strained the<br />

capacity at West Coast ports such as Los Angeles and Long Beach and congested the intermodal rail and<br />

road systems that connect these ports to inland destinations.<br />

As the first North American port of call on the trans-Pacific route from Asia, Canada has an opportunity to<br />

develop a sophisticated intermodal distribution network to serve the growing North American market,<br />

particularly the U.S. Midwest and <strong>Canadian</strong> consumption zones. The creation of an <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong><br />

<strong>Corridor</strong> linked by a state-of-the-art inland logistics facility will answer the growing need for additional North<br />

American gateway capacity and strengthen Canada’s position in the competitive world of international<br />

commerce. An inland port in Saskatchewan offers a favourable site wherein a program of strategic<br />

investment can result in a thriving inland cargo gateway complex at the heart of the <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

transportation network.<br />

1<br />

A forty-foot container equals two twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs).<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc.<br />

Page IN-1

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Project Goals and Objectives<br />

The overall purpose of the CISCOR <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong> business case paper is to articulate<br />

Saskatchewan’s competitive position as a centre for international trade processing and landside logistics<br />

operations. The paper provides a summary analysis of market, economic, transportation, and other<br />

business dynamics of Saskatchewan’s future development of an inland distribution and logistics service<br />

port. The stated goals of this report are:<br />

• Explore evolving global trade trends that necessitate a strategic North American inland port along a<br />

national transportation corridor.<br />

• Highlight the general benefits of locating an inland port at the convergence of the Pacific and Atlantic<br />

gateways in central Canada.<br />

• Define the strategic advantages that Saskatchewan will offer the region, North America and the global<br />

trade corridors through development of an inland port.<br />

• Demonstrate how the features of the inland port initiative will complement the parallel initiatives of<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> carriers, shippers, coastal ports and government initiatives.<br />

• Examine functions performed by successful inland port facilities and identify the concept elements that<br />

will allow Saskatchewan to build on its strengths and allow the region to carry forward a feasible option.<br />

• Estimate existing and forecasted freight flows, and institutional and organizational advantages of<br />

Saskatchewan where such a facility would be located.<br />

• Recommend future strategies to advance the inland port concept that will ultimately stimulate growth in<br />

various provincial industries and benefit the national economy.<br />

Study Process<br />

The study team collected and reviewed background materials regarding <strong>Canadian</strong> industries, freight and<br />

transport systems and interviewed key stakeholders including various shippers, CN and CPR railways and<br />

the ports of Vancouver, Montreal and Prince Rupert. Information on relevant case studies was also<br />

collected to compare the Saskatchewan project with other initiatives. The market opportunities and<br />

economic aspects were subsequently analysed and interpreted.<br />

A number of study constraints should be noted:<br />

• The study was exploratory in nature, designed to identify issues and opportunities for a <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

inland freight transport centre.<br />

• Macro-level analyses and provisional conclusions were derived from a limited set of indicators in part<br />

due to corporate restrictions in disclosing commercially-sensitive information.<br />

• The indicators, together with other transport operating statistics and exclusive consultations with<br />

industry stakeholders, may be used in further analysis to assess the micro-economic benefits of the<br />

project.<br />

Copyright 2007: Saskatchewan Agrivision Corporation Inc.<br />

Page IN-2

January 2007<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Intelligent</strong> <strong>Super</strong> <strong>Corridor</strong> - <strong>Smart</strong> <strong>Inland</strong> <strong>Port</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

Global Industry Trends and Conditions<br />

Growth in Containerized Trade and Asian Market<br />

Containerized trade is the fastest growing marine sector today and, coupled with the expansion of global<br />

manufacturing into Asia, has led to explosive trade growth between North America and the Far East. In the<br />

past five years, container trade in<br />

North America has increased at a<br />

Figure 1-1. Global Growth in Containerized Trade<br />

compound annual growth rate of 6.85<br />

percent per year reaching 48 million<br />

TEU in 2005. The largest volume of<br />

700<br />

600<br />

that trade is along the trans-Pacific<br />

500<br />

eastbound route, which grew by 7.5<br />

400<br />

percent in 2003, 17 percent in 2004,<br />

and 14 percent in 2005.<br />

300<br />

Approximately 24 million TEUs of<br />

200<br />

North American trade moved through<br />

West Coast ports with Asian traffic<br />

100<br />

representing approximately 18 million<br />

TEUs. North American container trade<br />

2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014<br />

is predicted to soar by 50 percent to<br />

North America World<br />

72 million TEUs by 2015. As imports<br />

Source: TranSystems, Containerization International statistics<br />

to North America continue to increase,<br />

freight volumes are expected to double and even triple at the busiest ports by 2020.<br />

Million of TEUs<br />

Currently, more than 60 percent of all North American container trade is with Asia, predominantly from<br />

China and Hong Kong. Container traffic to and from Asia is expected to grow at a higher rate than the<br />

world average in the next decade. China is expected to see the majority of the expansion, as it has in the<br />

last five years, and solid growth is expected in South Asia. Overall, Asia's share of containerized exports is<br />

Figure 1-2. 2015 Global Distribution of Container Volumes<br />

Central/South America<br />

6%<br />

North America<br />

13%<br />

Europe<br />

17%<br />

Australia/New<br />

Zealand/Pacific<br />

2%<br />

Source: UNESCAP 2005<br />

Africa<br />

3%<br />

North Asia<br />

8%<br />

Middle East<br />

2%<br />

South/Southeast Asia<br />

16%<br />

East Asia<br />

33%<br />

expected to rise to 64 percent in 2015; the<br />

share of containerized imports is expected to<br />

rise to 53 percent (UNESCAP, 2005).<br />

The <strong>Port</strong> of Hong Kong, currently the world’s<br />

largest port, handled 23.2 million containers in<br />