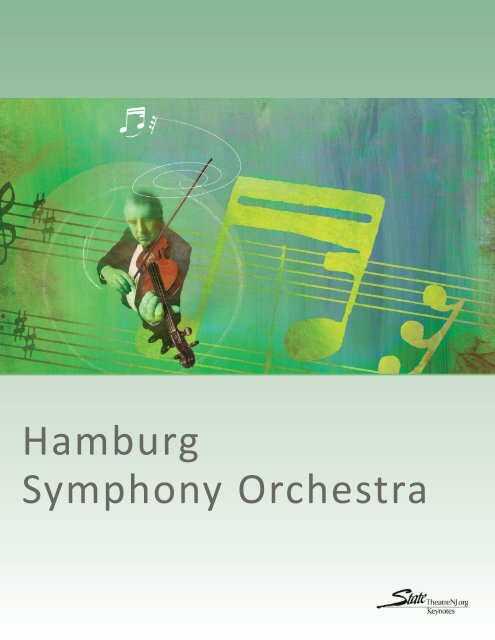

Hamburg Symphony Orchestra - State Theatre

Hamburg Symphony Orchestra - State Theatre

Hamburg Symphony Orchestra - State Theatre

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Hamburg</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>

Welcome<br />

2<br />

The <strong>State</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> in New Brunswick, NJ<br />

welcomes you to the performance of the<br />

<strong>Hamburg</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong>.<br />

These Keynotes provide information to help<br />

you take in the performance with a wellinformed<br />

ear and eye. We hope that the guide<br />

will add to your understanding and enjoyment<br />

of the concert and inspire you to continue<br />

exploring the rich world of classical music.<br />

Contents<br />

Welcome ................................................2<br />

Meet the <strong>Orchestra</strong> ............................3<br />

Jeffrey Tate, Conductor ....................4<br />

Guy Braunstein, Soloist ....................5<br />

A Closer Look: The Romantic Era..6<br />

Vaughan Williams................................7<br />

Johannes Brahms ................................8<br />

Meet the Composers ........................9<br />

Antonín Dvořák..................................10<br />

Decoding the Program Page........11<br />

Are You Ready?..................................12<br />

Keynotes are made possible by a<br />

generous grant from Bank of<br />

America Charitable Foundation.<br />

The <strong>State</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong>’s education program is funded in part by Bank of America Charitable Foundation, Colgate-<br />

Palmolive, The Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, E & G Foundation, Gannett Foundation, The William G. & Helen C.<br />

Hoffman Foundation, The Horizon Foundation for New Jersey, Johnson & Johnson Family of Companies, J. Seward<br />

Johnson, Sr. 1963 Charitable Trust, Karma Foundation, McCrane Foundation, MetLife Foundation, Mid Atlantic Arts<br />

Foundation, National Starch, New England Foundation for the Arts, New Jersey <strong>State</strong> Council on the Arts,<br />

Pennsylvania Performing Arts on Tour, PNC Foundation, Bill & Cathy Powell, The Provident Bank Foundation,<br />

PSE&G, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, TD Bank, and Wachovia Wells Fargo Foundation. Their support is<br />

gratefully acknowledged.<br />

The <strong>State</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> Series is made possible through the generous support of<br />

The Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation.<br />

Funding has been made possible in<br />

part by the New Jersey <strong>State</strong><br />

Council on the Arts/Department of<br />

<strong>State</strong>, a partner agency of the<br />

National Endowment for the Arts.<br />

Continental<br />

Airlines is the<br />

official airline<br />

of the <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>Theatre</strong>.<br />

The Heldrich<br />

is the official<br />

hotel of the<br />

<strong>State</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong>.<br />

Keynotes are produced by the Education<br />

Department of the <strong>State</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong>,<br />

New Brunswick, NJ.<br />

Mark W. Jones, President & CEO<br />

Lian Farrer, Vice President for Education<br />

Online at www.<strong>State</strong><strong>Theatre</strong>NJ.org/Keynotes<br />

Keynotes for <strong>Hamburg</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

written and designed by Lian Farrer and Jennifer<br />

Cunha.<br />

© 2010 <strong>State</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong><br />

Find us at www.<strong>State</strong><strong>Theatre</strong>NJ.org<br />

Contact: education@<strong>State</strong><strong>Theatre</strong>NJ.org<br />

<strong>State</strong> <strong>Theatre</strong>, a premier nonprofit venue for the<br />

performing arts and entertainment.

Meet the <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

3<br />

Founded in 1957, the <strong>Hamburg</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> has both a national and<br />

international reputation for being one of the most original symphonies in the<br />

city. As the only orchestra housed in the <strong>Hamburg</strong> Music Hall, they have<br />

secured a key spot in <strong>Hamburg</strong>’s music scene. The orchestra’s first principal<br />

conductor, Robert Heger, has been succeeded by the likes of Imre Kertesz and<br />

Miguel Gómez-Martinez, with guest conductors including Christian<br />

Theilemann, Horst Stein, and Sebastian Weigle.<br />

The <strong>Hamburg</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong>, when not touring, can be heard in subscription<br />

series, including open-air concerts in the summer. One of theses series includes<br />

chamber music concerts, vocal recitals, and concerts devoted to silent films.<br />

The second is a series of concerts for children and young adults, including<br />

outreach programs to schools. In 2008, the orchestra further dedicated itself to<br />

the advancement of young musicians and established an Artist in Residence<br />

position that has featured clarinetist Martin Fröst and violinist Guy Braunstein.<br />

In 2009, Jeffrey Tate took over as Principal Conductor and Daniel Kühnel as<br />

General Manager and Artistic Director. Together, they have strengthened the<br />

orchestra’s connection with the city and increased their audience by 56%. The<br />

<strong>Hamburg</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> has featured some of the world’s most renowned soloists,<br />

including Frank Peter Zimmerman, Placido Domingo and Elisabeth Leonskaja.<br />

The orchestra has toured throughout Europe in Italy, Spain, Poland, Great<br />

Britain, Turkey, and France, taking it’s place as one of Europe’s foremost<br />

orchestras. This U.S. tour marks the first time the symphony as visited the <strong>State</strong>s<br />

since 2007.<br />

“From the warmth of the first<br />

horn chords and the airy<br />

lightness of the violins in the<br />

first movement, to the<br />

grandeur of the finale, the<br />

<strong>Hamburg</strong>’s performance was<br />

all one hoped for. There were<br />

moments when sections or<br />

individuals shone... when the<br />

orchestra itself seemed to<br />

dance."<br />

—Newsday

Jeffrey Tate, Conductor<br />

4<br />

British conductor Jeffrey Tate is one of the most<br />

renowned conductors of his generation. His current home is<br />

with the <strong>Hamburg</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> as Principal Conductor<br />

in Germany, but he has performed with nearly every major<br />

orchestra in the world.<br />

Music was not Maestro Tate’s first profession. He<br />

originally studied medicine at the University of Cambridge and<br />

was an eye surgeon in London for three years before joining<br />

the music staff at the Royal Opera Covent Garden in 1970. Tate<br />

made his conducting debut at Gothenburg Opera in 1978.<br />

Since then, he has become famous as a conductor of the music<br />

of Wagner and<br />

Strauss, along with music of the romantic and classical repertoires, 19th and<br />

“As the music moved under<br />

20th century British music, and contemporary music. In the 1982-83 season<br />

my hands, I suddenly felt<br />

alone, Tate conducted at the Royal Opera House, the Met in New York City,<br />

that I was doing something I<br />

and with the English Chamber <strong>Orchestra</strong>, eventually being appointed<br />

Principal Conductor in 1985.<br />

had been waiting to do all my<br />

Maestro Tate has conducted world premiere performances of Henze’s Il life.”<br />

Ritorno d’Ulisse at the Salzburg Festival and of Rolf Liebermann’s Der Wald<br />

— Jeffrey Tate<br />

in Geneva. Over the years, Tate has been appointed Music Director of the<br />

Rotterdam Philharmonic <strong>Orchestra</strong>, Principal Guest Conductor of the<br />

Orchestre National de France, and the Royal Opera House Covent Garden. He has also conducted performances at the<br />

Bastille Opera and the Châtelet in Paris, not to mention Palais Garnier and La Scala Milan. He has developed relationships<br />

with orchestras throughout the world, often returning to perform with them. These include the Berlin Philharmonic,<br />

Dresden Philharmonic, the Boston <strong>Symphony</strong>, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, and Sydney <strong>Symphony</strong>, to name a few.<br />

In 2001, Maestor Tate was named the Honorary Director of the National Italian Radio <strong>Orchestra</strong>. For the 2009-10<br />

season, he was nominated to become Chief Conductor of the <strong>Hamburg</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>. Already thinking ahead,<br />

Jeffrey Tate is scheduled to work on Billy Budd at the Bastille in Paris and also to do two complete cycles of Richard<br />

Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen during the 2013-14 season at Vienna <strong>State</strong> Opera.<br />

After more than four decades as a prominent conductor, there is no doubt that Maestro Tate has garnered many<br />

awards in his career. In 2001, 2002, and 2010, he was awarded the Franco Abbiati Prize, which is Italy’s most prestigious<br />

prize, for his work with <strong>Orchestra</strong> Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI, Teatro San Carlo in Napoli, and for the production of<br />

Götterdämmerung at La Fenice in Venice. Tate has also earned the titles of “Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur,” “Chevalier<br />

des Arts et des Lettres,” and Commander of the British Empire for his work.

Guy Braunstein, Soloist<br />

5<br />

Violinist Guy Braunstein was born in Tel Aviv, Israel.<br />

There, he studied the violin with Chaim Taub. When he<br />

came to New York, he then learned under Glenn Dicterow<br />

and Pinchas Zuckerman. His career as a soloist began at a<br />

young age and has continued to grow ever since. Through<br />

the years, he has played with the Isreal Philharmonic,<br />

Bamberg <strong>Symphony</strong>, Tonhalle Zurich, and Berliner<br />

Philharmoniker, to name a few.<br />

Over his prestigous career, Braunstein has collaborated<br />

with the likes of Issac Stern, Daniel Barenboim, Sir Simon<br />

Rattler, Jonathan Nott, Gary Bertini, and Angelika<br />

Kirschlager. In 2000, he was the youngest person in the<br />

history of the Berliner Philharmonker to be appointed<br />

concertmaster. He has kept his position and works with<br />

them for approximately four months per year.<br />

From 2003 to 2007, Braunstein served as Professor of<br />

Music in the University of the Arts (Universitaet der Kunst)<br />

in Berlin. Germany’s Rolandseck festival has had<br />

international stars including Emmanuel Pahud, Amihai Grosz, and<br />

François Leleux since Guy Braunstein took over as Music Director<br />

in 2006.<br />

During the 2010-11 season, Braunstein performed with Sofia<br />

Philharmonic <strong>Orchestra</strong> and Mozarteun <strong>Orchestra</strong> Salzburg. He<br />

also play-directed the Halle Staatskapelle and performed recitals<br />

and chamber music concerts throughout Europe, making stops in<br />

London, Jerusalem, Berlin, and Frankfurt. Guy is also a member of<br />

the West-Eastern Divan <strong>Orchestra</strong>.<br />

Guy Braunstein’s repertoire is quite impressive, covering 19<br />

composers and 30 pieces. He covers Bach, Beethoven, Haydn,<br />

Mozart, and Vivaldi and does so with a rare violin made in 1679 by<br />

Francesco Ruggieri.<br />

Ruggieri’s Violin<br />

Francesco Ruggieri (1620-<br />

1695) is the first in a family<br />

of violin crafters out of<br />

Cremona, located in northern<br />

Italy on the left bank of the<br />

Po River. Often thought of as<br />

the first pupil of famous<br />

violin maker, Nicolo<br />

Amati, Ruggieri<br />

patterned his<br />

instruments on Amati’s<br />

designs. Ruggieri’s<br />

instruments are known<br />

for their rich, full tone<br />

and beautiful<br />

craftsmanship, although<br />

he is more known for his cellos.

A Closer Look :<br />

The<br />

Romanc Era<br />

6<br />

JMW Turner, “Chichester Canal” (1828)<br />

ROMANTIC<br />

1. displaying or expressing love or<br />

strong affection.<br />

2. ardent; passionate; fervent.<br />

3. imbued with or dominated by<br />

idealism, a desire for adventure,<br />

chivalry, etc.<br />

4. (usually initial capital letter)<br />

pertaining to or characteristic of<br />

a style of literature and art that<br />

subordinates form to content,<br />

encourages freedom of<br />

treatment, emphasizes<br />

imagination, emotion, and<br />

introspection, and often<br />

celebrates nature, the ordinary<br />

person, and freedom of the spirit<br />

(contrasted with classical).<br />

5. of or pertaining to a musical<br />

style characteristic chiefly of the<br />

19th century and marked by the<br />

free expression of imagination<br />

and emotion, virtuosic display,<br />

experimentation with form, and<br />

the adventurous development of<br />

orchestral and piano music and<br />

opera.<br />

6. fanciful; impractical; unrealistic.<br />

7. imaginary, fictitious, or<br />

fabulous.<br />

Johanne Brahms’, whose work you will hear at the concert is a product of<br />

music’s Romantic Era (roughly 1800-1910). The Romantic movement<br />

encompassed not only music, but architecture, visual art, literature, dance,<br />

theater, and philosophy as well.<br />

The roots of Romanticism in music were in the preceding Classical Era, where<br />

18th-century composers such as Mozart and Haydn perfected the musical<br />

expression of the Age of Reason. Their works emphasized clarity and proportion<br />

in both structural and harmonic language. In their orchestral works (as opposed<br />

to their operas), the music stood on its<br />

own, unconnected to ideas, images, drama, “People often complain that<br />

or other non-musical elements.<br />

music is ambiguous, that their<br />

During the Romantic Era, music moved ideas on the subject always seem<br />

from the abstract into the realm of the so vague, whereas everyone<br />

representational. Now it might tell a story, understands words. With me it is<br />

conjure an image, stir emotions. The genre exactly the reverse—not merely<br />

became known as “program music”—<br />

with regard to entire sentences,<br />

music that has an underlying narrative or<br />

but also as to individual words.<br />

non-musical meaning. The emotional<br />

These, too, seem to me so<br />

content was typically intense. This was the<br />

ambiguous, so vague, so<br />

era that gave us the operatic mad scene,<br />

unintelligible when compared<br />

the symphonic shipwreck, and the<br />

with genuine music, which fills<br />

revolutionary étude. Besides love, popular<br />

subjects in Romantic music included<br />

the soul with a thousand things<br />

nature, introspection, imagination, and the better than words.”<br />

supernatural. Political revolutions in Europe —composer Felix Mendelssohn<br />

during the 19th century created a wave of<br />

nationalism that was reflected in the music of the Romantic Era. Composers<br />

proudly integrated traditional music of their homeland into their works.<br />

Looking for a broader palette with which to paint their musical pictures,<br />

Romantic composers loosened and expanded the formal conventions of the<br />

Classical Period, as applied to form, melody, harmony, tonal relationships, and<br />

instrumentation. They still wrote symphonies, concertos, sonatas, and the like,<br />

but they also created symphonic poems, program symphonies, fantasies,<br />

nocturnes, impromptus, mazurkas, song cycles and other new genres that<br />

expressed their aesthetic ideas.

Vaughan Williams:<br />

7<br />

The Wasps Overture<br />

Wasps are not loveable insects. In the summer and fall, they<br />

swarm around visitors at street cafes, landing on whatever is<br />

sweet on the table and often enough in drinks. It is impossible to<br />

get rid of them without attracting even more of the creatures.<br />

This appears to have been the case in antique times as well, for<br />

the Greek dramatist Aristophanes, in his comedy The Wasps from<br />

422 BC, used wasps as a metaphor for litigious citizens who took<br />

every opportunity to engage in legal battles. The historical<br />

background for this was an increase in the remuneration for<br />

citizens who served as trial judges. In ancient Athens, with its<br />

specific early form of democracy, being a judge was not an<br />

institutionalized profession, but rather one of the responsibilities<br />

required of full citizens. Following the laws of the city, judges<br />

arrived at their decisions after both parties in a case – the accuser<br />

and defendant or their representatives – had presented their<br />

positions. For this, the judge received a kind of expense<br />

allowance, which was increased by a third under the rule of Cleon.<br />

As a result, the willingness of the Athenians to go to court grew<br />

dramatically, which Aristophanes used as the point of departure<br />

for his comedy. He dealt with this situation in a highly satirical<br />

manner by making the chorus of amateur judges into wasps and<br />

the stylus with which the decision was written a wasp’s stinger.<br />

Ralph Vaughan Williams composed his incidental music in<br />

1909 for a performance of The Wasps at Trinity College in<br />

Cambridge. He wrote not only the usual overture and interludes<br />

between scenes, but also set a number of complete scenes to<br />

music, so that the entire incidental music for the play lasts almost<br />

two hours. The music is rarely performed in its entirety, but<br />

Vaughan Williams himself arranged a suite consisting of five<br />

instrumental pieces. The suite begins with an overture that is in<br />

itself a splendid concert piece. The wasps can be heard<br />

immediately; the instruments as they enter conjure up a swarm of<br />

insects that buzz aggressively around the ears of the listeners.<br />

This introduction is followed by the spirited presentation of three<br />

themes sung by the chorus in the course of the play. This lively<br />

music exudes energy and high spirits. It was particularly<br />

important to Jeffrey Tate to bring music by an English composer<br />

to audiences on the <strong>Hamburg</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>’s American<br />

tour. Vaughan Williams’s setting of music for the ancient comedy<br />

is modern and delightful, full of striking instrumental effects<br />

without literally invoking antique musical conventions.<br />

© 1994 Columbia Artists Management Inc.<br />

Ralph<br />

Vaughan<br />

Williams<br />

was born in<br />

1872 in the<br />

Cotswold<br />

village of<br />

Down<br />

Ampney. He attended the Charterhouse School<br />

followed by Trinity College in Cambridge. Later he<br />

was trained by Hubert Parry and Charles Stanford at<br />

the Royal College of Music.<br />

Until he was 32-years-old Vaughan Williams<br />

showed no desire to be anything other than an<br />

industrious and efficient church musician. Fortunately<br />

after a few years at his first professional post as<br />

organist at the St. Barnabas Church in London he was<br />

introduced to English folk music and his former<br />

interest in church music was overtaken by his passion<br />

for folk songs. This gave Vaughan Williams the<br />

materials he needed to build new musical works.<br />

Between 1905 and 1907 he wrote three Norfolk<br />

rhapsodies for orchestra and produced a major<br />

choral work, “Toward the Unknown Region” in the<br />

English style, however inspired by American poet<br />

Walt Whitman. He completed his first important<br />

piece of work just two years later—Fantasia on a<br />

Theme by Thomas Tallis.<br />

After the war he joined the faculty of the Royal<br />

College of Music teaching composition. He also<br />

became the conductor of the Bach Choir in London<br />

from 1920-1926. Premieres of his works became<br />

events of national significance. In the decade<br />

following World War I he composed numerous<br />

masterpieces still heard today. In 1935 he received<br />

one of the highest awards a composer can receive –<br />

the Order of Merit. He died on August 26, 1958.

Johannes Brahms:<br />

8<br />

Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77<br />

In 1853, Brahms embarked on a concert tour with the Hungarian violinist Eduard Hoffmann (a.k.a. Reményi). It was during<br />

their stop at Göttinger, near Hanover, that Brahms came to meet Joseph Joachim, the virtuoso violinist – also a composer –<br />

with whom he established an immediate rapport, flourishing into their long friendship. Joachim proved to be enormously<br />

influential in Brahms’ career, as well as in the younger man’s development as a composer. The two shared an identity of<br />

artistic outlook, and a great admiration for each other’s works; together they stood firmly against the “New German School”<br />

as exemplified by Liszt and, later, Wagner. It was at Joachim’s suggestion that Brahms met Robert Schumann and his wife<br />

Clara, both of whom were to become important in his life as well as in his further development as a composer.<br />

Equally important, as a conductor Joachim introduced several of Brahms’ orchestral works, thus garnering recognition for<br />

the younger composer and establishing his reputation, especially in England where the virtuoso/conductor was regarded with<br />

high esteem. Early on, Brahms benefited immensely from Joachim’s advice regarding orchestration, and from hearing<br />

Joachim’s Hanover Quartet perform some of his chamber works. It was not surprising, then, that when Brahms wrote his<br />

masterful Violin Concerto in 1878, he would ask his friend for technical advice regarding the solo part: “I will be satisfied if<br />

you will let me have a few words, and perhaps even write some in the score: difficult, uncomfortable, impossible, etc.”<br />

Joachim—for whom the work was composed and to whom it is dedicated—assured Brahms that “…most of the material is<br />

playable, but I wouldn’t care to say whether it can be comfortably played in an overheated concert hall until I have played it<br />

through to myself without stopping.” Indeed, the violinist provided some invaluable guidance in the form of fingerings and<br />

bowings, but ultimately, Brahms adhered to his original ideas. Joachim did also write the cadenza for the first movement,<br />

although, many other violinists have provided their own cadenzas since then.<br />

Joachim introduced Brahms’ Violin Concerto on New Years Day, 1879, at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, with the composer at<br />

the podium. The premiere of the work was not entirely well received, and the infamous critic Hans von Bülow called it “clumsy<br />

and devoid of flexibility,” further describing the work as being “written not for but against the violin.” However, through the<br />

dedicated advocacy of Joachim, the concerto soon gained its deserved recognition and a very secure place in the repertoire.<br />

A later advocate of the work, Bronislaw Huberman would answer Bülow’s criticism with the words: “Brahms’ concerto is<br />

neither against the violin nor for violin with orchestra but…for violin against orchestra – and the violin wins.”<br />

The main theme of the first movement (Allegro non troppo) is announced by violas, cellos, bassoons and horns. This<br />

subject, and three contrasting song-like themes, together with an energetic dotted figure, marcato, furnish the thematic<br />

material of the movement. The solo violin is introduced, after almost a hundred measures for the orchestra alone, in an<br />

extended section, chiefly of passagework, as a preamble to the exposition of the chief theme. With great skill, Brahms<br />

unleashes his two essentially unequal forces: the tender, lyric violin and the robust orchestra. In the expansive and emotional<br />

development, the caressing and delicate weaving of the solo instrument about the melodic outlines of the song themes in<br />

the orchestra is most unforgettable. A particular high point is provided when the long solo cadenza merges with the serene<br />

return of the main theme in the coda that concludes the movement.<br />

This feature is even more pronounced in the second movement (Adagio), where a dreamy oboe introduces the main<br />

theme against the background provided by the rest of the woodwinds. The solo violin, makes its compliments to the main<br />

theme, and announces an ornamental second theme. Adding the warmth of its tone, the soloist proceeds to embroider its<br />

arabesques and filigrees upon the thematic material with captivating and tender beauty.<br />

The Finale (Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace) is a virtuoso’s tour de force, built upon a compact rondo structure,<br />

containing three distinct themes. The jovial main theme, in thirds, is stated at once by the solo violin. The thematic material<br />

and its eventual elaboration provide many hazards for the soloist: precarious passagework, double-stopping and arpeggiated<br />

figurations. But the music, inhabiting the carefree world of Hungarian gypsies, is quite spirited and fascinating—music of<br />

incisive rhythmic charm and great zest, which in turn pays tribute to the composer’s friend and colleague, Joachim. After the<br />

proceedings accelerate to a quick march tempo based on the main theme, the brilliant coda finally slows down to bring the<br />

concerto to its elegant conclusion.<br />

© 1994 Columbia Artists Management Inc.

Meet the Composers<br />

9<br />

Born in 1833 in <strong>Hamburg</strong>, Germany, composer and pianist Johannes Brahms<br />

was the son of a double-bass player, who gave him his first musical training. The<br />

young Brahms gave a few public concerts in <strong>Hamburg</strong>, but did not become well<br />

known as a pianist until he made a concert tour at the age of 19. In later life, he<br />

frequently took part in the performance of his own works, whether as soloist,<br />

accompanist, conductor, or participant in chamber music.<br />

Brahms spent most of his professional life in Vienna—a major music capital—<br />

where some looked to him as the successor to Beethoven. Like Beethoven, Brahms<br />

was both a traditionalist and an innovator. His music is grounded on the structures<br />

and compositional techniques of the Baroque and Classical masters. Though he<br />

employed familiar structural underpinnings, Brahms created a bold new harmonic<br />

language that was anything but traditional, challenging the existing conventions of<br />

tonal music. With a point of view that looked both backward and forward,<br />

Brahms came to be an important influenced for both conservative and<br />

modernist composers who followed him.<br />

Brahms resembled Beethoven temperamentally, as well as musically. Both<br />

enjoyed nature, and both had a reputation for gruffness, especially with<br />

adults. Still, Brahms had a number of strong friendships with other<br />

musicians: composer Robert Schumann and his wife, the pianist Clara Schumann;<br />

violinist Joseph Joachim; and “waltz king” Johann Strauss II. Though he never married,<br />

he is thought to have carried a lifelong—though unrequited—passion for Clara Schumann.<br />

Check out the Johannes Brahms WebSource<br />

at: www.johannesbrahms.org<br />

and the American Brahms Society at<br />

http://brahms.unh.edu/<br />

Composer Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) wrote in a variety of classical<br />

forms, including symphonies, concertos, ‘symphonic poems,’ chamber music,<br />

choral and piano music, and even opera. His music is characterized by a fusion<br />

of European Romantic style with the idioms and melodies of the folk music of<br />

the composer’s native Bohemia.<br />

Dvořák was the son of a butcher (who also worked as a professional zither<br />

player). Displaying talent at an early age, the boy took lessons in organ, viola,<br />

piano and basic composition. After graduating from the Prague Organ School,<br />

he became a member of the new Provisional <strong>Theatre</strong> orchestra, which was conducted by the Czech nationalist composer<br />

Bedrich Smetana.<br />

Eventually Dvořák left the orchestra to devote himself full time to composing. By his early 30s, he was sufficiently well<br />

known for Johannes Brahms to recommend him to the music publisher Simrock; the company commissioned Dvořák’s hugely<br />

successful Slavonic Dances (1878). His music was increasingly performed to great acclaim, leading to new commissions and<br />

invitations to tour abroad. England was especially hospitable to the composer, hosting frequent visits, commissioning new<br />

works, and even awarding him an honorary Cambridge doctorate. He visited Russia in 1890, continued to launch new works<br />

in Prague and London and began teaching at the Prague Conservatory in 1891.<br />

Dvořák’s fame was not limited to Europe. From 1892-1895 he served as director of the National Conservatory in New York<br />

City, where he also taught composition. In New York he wrote his best-known work—the Ninth <strong>Symphony</strong> (“From the New<br />

World”), as well as the Cello Concerto in B minor. The composer’s American sojourn included a summer in the Czechspeaking<br />

community of Spillville, Iowa, where he wrote two of his most beloved chamber works: the String Quartet in F (“The<br />

American”), the String Quintet in E-flat.<br />

Financial disputes and family ties took him back home, where he focused on writing opera and chamber music. He served<br />

as director of the Conservatory in Prague from 1901 until his death in 1904.

Antonín Dvořák:<br />

10<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No. 7 in D minor,<br />

Op. 70, B. 141<br />

Antonín Dvořák<br />

Born September 8, 1841 in Nelahozeves<br />

Died May 1 , 1904 in Prague<br />

Dvořák’s <strong>Symphony</strong> No. 7 was accepted immediately by conservatives and progressives alike. By that time, the composer<br />

had already achieved success both at home and abroad. On March 13, 1884 he conducted his Stabat Mater, followed by a<br />

concert of his orchestral works in London. The triumph of these performances led to many new invitations to England. He<br />

was showered with orders from home and abroad, including the supreme honor of membership to the London Philharmonic<br />

Society, accompanied by their request that he compose a new symphony for them.<br />

The rugged style of this symphony can be compared with that of Dvořák’s supporter, Johannes Brahms, who at that time<br />

was renowned as a writer of symphonies. It is possible that through this work Dvořák wanted to become an artistic rival; in<br />

fact, the <strong>Symphony</strong> No. 7 is noticeably like Brahms in character. It should be added, however, that this work has an even<br />

greater similarity of style to Dvořák’s own “Little” <strong>Symphony</strong> No. 4 in D minor, which he wrote before Brahms had composed<br />

his first symphony.<br />

The Seventh <strong>Symphony</strong> was published in Berlin in 1885 and received its premiere performance in London’s St. James Hall<br />

on April 22, 1885, with the London Philharmonic and composer as conductor. It is interesting to note that after the<br />

performance, Dvořák deleted approximately forty measures from the second movement “in order that the work should not<br />

contain a single unnecessary note.” The German conductors who zealously performed the symphony were Hans von Bülow,<br />

Hans Richter and Arthur Nikisch; the latter also conducted it on his American tour.<br />

The first movement, Allegro maestoso, is in the key of D minor. The opening theme is given to the violas and cellos, which<br />

is taken up and varied slightly by the clarinets. The second theme, of an energetic character, follows and is derived from the<br />

Allegro of the Hussite Overture. It is presented by the strings and reaches a climax as the first theme’s restatement begins.<br />

The vigorous development section precedes a compressed recapitulation; unusual in that it begins in an unorthodox key but<br />

returns to the tonic by the time its conclusion is reached. The movement ends with an extended, somewhat tense, coda.<br />

The second movement, Poco adagio, in the relative major key of F major, introduces one of Dvořák’s more inspired<br />

melodies. This is followed by a theme, presented by the horns and clarinet, reminiscent of Tristan und Isolde. After a<br />

passionate dialogue, the movement returns to the principle theme, begun from its middle, providing a most unusual, but<br />

effective device.<br />

The third movement, a Scherzo in vivace tempo in the key of the symphony’s minor tonic and cast in duple time, achieves<br />

some rather piquant rhythmic effects through the use of syncopation. The two themes alternate between various choirs of the<br />

orchestra and maintain the lively, dance-like character of the movement. The Trio section provides contrast to the Scherzo<br />

section not only in its tempo, marked Poco meno mosso, but also in its key of G major and its use of an imitative motif. The<br />

return of the Scherzo is slightly telescoped but has the addition of a charming cadential theme at the close.<br />

The Finale: Allegro, in the key of D minor and in duple time, is rich in thematic material. A march-like theme is the principle<br />

motive and this is presented in numerous guises, alternating with new material. The development section presents the<br />

themes already heard in creative combinations demonstrating a remarkable resourcefulness on Dvořák’s part. A rapid<br />

crescendo brings the movement to its recapitulation. Dvořák, utilizing ten majestic concluding chords in D major, brings the<br />

work to a triumphant resolution.<br />

© 1999 Columbia Artists Management Inc.

Decoding the Program Page<br />

11<br />

The program book (or playbill) contains helpful information about the performance. It lists the pieces the orchestra will play<br />

in the order they will play them. It tells you the name of each piece, the name of the composer, and the movement headings.<br />

If you’re not familiar with a piece, the program will help you keep track of what’s going on and know when the piece is<br />

finished. The program page for the Philharmonic of Poland looks like this:<br />

A MOVEMENT is a section<br />

within a musical piece, like a<br />

chapter in a book. Individual<br />

movements are usually<br />

referred to by the tempo<br />

marking that the composer<br />

has written at the beginning<br />

of the section. During the<br />

concert, there is usually a<br />

brief pause between<br />

movements, during which the<br />

audience should remain silent.<br />

Today’s concert etiquette<br />

dictates that you hold your<br />

applause until the entire piece<br />

is finished.<br />

OPUS NUMBER<br />

(among all of Brahms’<br />

published works)<br />

There are several ways that<br />

works of classical music can<br />

be identified. The system is<br />

not consistent from one<br />

composer to another.<br />

COMPOSER<br />

SOLOIST<br />

• NUMBER - where the piece<br />

falls in the catalogue of the<br />

composer’s works for a<br />

specific musical form (such<br />

as the Ninth <strong>Symphony</strong> or<br />

the Bassoon Concerto No.<br />

2).<br />

• OPUS NUMBER - where<br />

the piece falls in the entire<br />

catalogue of the composer’s<br />

works, in the order they<br />

were published. The lower<br />

the number, the earlier it<br />

was published (but not<br />

necessarily when it was<br />

written). Opus is a Latin<br />

word meaning “work.”<br />

FUNDING CREDITS<br />

Many arts institutions<br />

(including the <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>Theatre</strong>) are not-for-profit<br />

organizations;<br />

acknowledging donors<br />

and sponsors is an<br />

important part of staying<br />

in business.<br />

what KEY the<br />

music starts in

Are You Ready?<br />

12<br />

To Clap, or Not to Clap...<br />

People who’ve never attended an orchestra concert are<br />

sometimes apprehensive about applauding at the wrong<br />

time. If you’re one of those people, here are some general<br />

rules to guide you:<br />

• Just before the concert begins, the audience will applaud<br />

the arrival onstage of the concertmaster (the first violinist,<br />

who acts as the leader of the musicians). They’ll applaud<br />

again when the conductor and soloist(s) enter.<br />

• If they’ve liked the performance, the audience will<br />

applaud at the end of each piece of music on the<br />

program. Applauding between the movements or sections<br />

of a piece is generally frowned upon, even if there’s a<br />

long pause. Many people believe that applauding<br />

between movements breaks the spell or momentum of<br />

the piece. If you’re not sure when a piece is finished,<br />

check the program to see how many movements there<br />

are, or applaud only when the conductor turns to the<br />

audience and bows.<br />

Some Additional Tips on<br />

Concert Etiquette<br />

• All it takes is one ringing cell phone, noisy latecomer, or<br />

loudly whispered conversation to spoil a concert for the<br />

entire audience. Be sure to arrive on time and turn off<br />

phones, pagers, beepers, and other electronic devices<br />

before the performance begins. Hold your comments and<br />

conversation until intermission.<br />

• Even if you’re not making or receiving calls, those little<br />

squares of light are a distraction to anyone sitting near<br />

you; please refrain from texting, checking messages, etc.<br />

during the concert.<br />

• Though concertgoers are doing it more and more these<br />

days, it’s generally considered impolite to leave the hall<br />

while the audience is still applauding. And if you leave too<br />

soon, you’ll miss the encore, if the orchestra plays one!<br />

• When a piece has ended, the conductor (and soloist, if<br />

there is one) may leave the stage and then return for<br />

curtain calls, depending on the level of applause.