You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

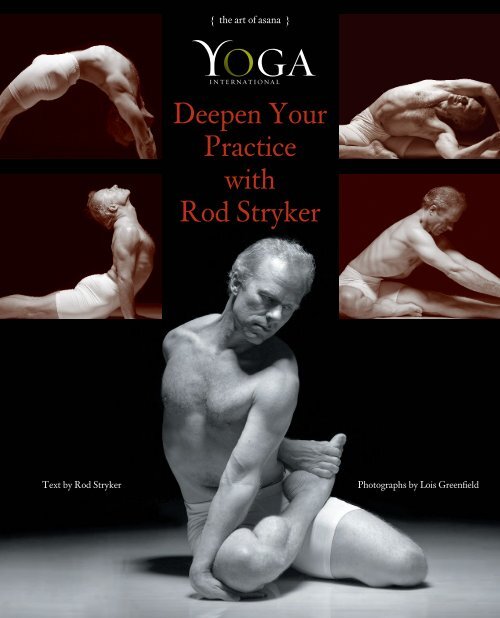

{ the art of asana }<br />

Deepen Your<br />

Practice<br />

with<br />

Rod Stryker<br />

Text by Rod Stryker<br />

Photographs by Lois Greenfield

{Art of Asana}<br />

Urdhva dhanurasana (upward-facing bow) is an expression<br />

of the joy and fearlessness that is the hallmark of a successful<br />

yoga practice. This pose opens the body and awakens the mind.<br />

Upward-Facing Bow<br />

(Urdhva dhanurasana)<br />

The ancient masters saw the body as a bridge to the infinite.<br />

Their exploration of how it can be used to access Spirit’s<br />

sublime beauty and power is what we know today as hatha<br />

yoga. The approach of these masters was based on two key<br />

insights: all the forces of nature are contained in our physical<br />

form, and fulfillment—both material and spiritual—follows<br />

effortlessly as we develop mastery over these forces within<br />

the body.<br />

We often judge our practice by what our body can or can’t<br />

do: the number of sun salutations, how deep we are in a pose,<br />

how long we can hold it, even which cross-legged seat we use<br />

for meditation. None of these are true barometers of practice.<br />

While the body is indeed where the journey of yoga begins<br />

for many of us, perfection of the body is not the goal. In yoga<br />

your body is a means, not the end.<br />

I am often asked how to measure the quality of a yoga<br />

practice. “How do I know that the practice I am doing is the<br />

best one for me?” The answer: by its effect. The quality of your<br />

practice is ultimately measured by its effect on the quality of<br />

your life. In other words, mastery in yoga is mastery of life.<br />

Urdhva dhanurasana, like all poses, benefits our body,<br />

mind, energetic systems, and emotions in unique ways. By<br />

encapsulating the essence of backbending, the pose propels us<br />

toward the ultimate embodiment of yoga: fearlessness and joy.

Sukha, the Sanskrit term for ease,<br />

happiness, or pleasure, literally means “good<br />

space.” The masters tell us we suffer (duhkha)<br />

because “stuff” overshadows the inherent goodness<br />

of our inner space. It settles between cells,<br />

organs, vertebrae, along medians, and in our<br />

fields of perception. The glory of backbends is<br />

their ability to disperse this “stuff,” thus revealing<br />

our natural state of ease.<br />

Urdhva dhanurasana increases the vital force<br />

around the heart (pran), as well as the distributive<br />

force (vyana) throughout the body, thus<br />

increasing the breadth of courage and awareness.<br />

The pose stimulates both mind and body—the<br />

net result is exultation, awakening radiance,<br />

delight, and compassion.<br />

This pose is the culmination of backbends,<br />

and so is beyond the reach of many students.<br />

Those who can do it often experience pain or<br />

harm their lower back or shoulders. Thus, the<br />

challenge is to move toward accomplishing the<br />

pose safely and effectively.<br />

The principles of sequencing (vinyasa krama)<br />

require us to systematically prepare the body<br />

for the most challenging pose in a practice (the<br />

apex). Poses that prepare us for the apex have<br />

a similar physical, mental, and energetic action,<br />

but are simpler and more accessible. Methodical<br />

sequencing has four steps: First, identify the<br />

apex. Then analyze the focal points—the areas<br />

of the body most involved—in terms of flex ibility,<br />

stability, and correct actions. Next, choose<br />

the appropriate preparatory poses, and, finally,<br />

place them in order.<br />

The focal points for urdhva dhanurasana<br />

include flexibility along the front body, specifically<br />

in the quadriceps, hip flexors, intercostal muscles,<br />

shoulders, wrists; and strength and stability<br />

in the sacrum, arms, shoulders, wrists. Correct<br />

actions include internal rotation of thighs, upper<br />

arms, and the engagement of the hamstrings.<br />

The postures pictured here address many<br />

of these focal points. I consistently use them<br />

(or variations) to prepare students for deep<br />

backbends. They should be part of a complete<br />

practice that includes sun salutations, standing<br />

postures, arm strengthening, and counterposes.<br />

Asana practice enhances physical well-being,<br />

but its greatest effect is on the mind and pranic<br />

(energy) body. Upward-facing bow and the postures<br />

that build toward it inspire us to reach for<br />

greatness and increase our capacity and passion<br />

for life.<br />

CHAIR POSE (utkatasana) is an<br />

excellent preparation for backbending.<br />

It strengthens the lower<br />

back, opens the chest and shoulders,<br />

and establishes the correct action<br />

to stabilize the sacrum: tailbone<br />

draws into the body (pelvic tilt),<br />

while upper arms externally rotate<br />

and draw down into the shoulder<br />

sockets.<br />

Hint: On inhale, lift chest and<br />

collarbones. On exhale, tailbone<br />

tilts toward the heels.<br />

1<br />

COBRA VARIATION (bhujangasana)<br />

deepens the lumbar curve, engages<br />

lower abdominal lift, promotes<br />

expansion of intercostals and<br />

lengthening of the upper spine.<br />

Hint: Keep the legs active: shins in,<br />

inner thighs engaged, and spiral<br />

toward the ceiling. Arm draws down<br />

into the shoulder socket. Exhale,<br />

navel toward spine.<br />

4

SIDE-ANGLE POSE (parshvakonasana)<br />

is a dynamic stretch for the intercostals<br />

and shoulders.<br />

Hint: Stretch the back body and front body<br />

equally. Back leg muscles engage, draw<br />

tailbone into the body, expand the kidneys.<br />

WARRIOR I VARIATION<br />

(virabhadrasana I) builds on<br />

the pelvic tilt of chair pose<br />

by deepening the opening<br />

of the chest. It dynamically<br />

stretches the hip flexors and<br />

quadriceps.<br />

Hint: Inhale, lift collarbones.<br />

Exhale, expand and flatten<br />

lumbar spine, tailbone toward<br />

the front heel. Powerfully,<br />

internally rotate the<br />

back thigh.<br />

2 3<br />

BOW (dhanurasana) enlivens the<br />

action of the legs, chest, and pelvis.<br />

Its similarity to urdhva dhanurasana<br />

(in action and shape) make it an ideal<br />

preparation because its action and<br />

even its shape are practically identical<br />

to the apex pose, but it is more<br />

accessible.<br />

Hint: Draw the tailbone through the<br />

thighs toward the floor.<br />

ONE-LEGGED CAMEL (ekapada<br />

ushtrasana) deepens the action of<br />

warrior I, in particular deepening<br />

the release for front thighs and<br />

pelvis.<br />

Hint: Engage the inner thigh by<br />

lifting and contracting the muscle<br />

toward the femur. Maintain the<br />

internal rotation on the back leg.<br />

Lift lower abdomen and collarbones.<br />

The front knee is over the heel.+<br />

© Lois Greenfield<br />

5<br />

6

{Art of Asana}<br />

Urdhva mukha shvanasana (upward-facing dog) is an exhilarating, majestic pose that<br />

will boost your self-confidence, expand your mind, and open your heart.<br />

Upward-Facing-Dog<br />

(Urdhva Mukha Shvanasana)<br />

WHAT IS YOGA? My first teacher had a simple answer: “Yoga is life,”<br />

a way of being fully and vibrantly alive. Yoga practice, it follows, should<br />

empower us to see both our internal<br />

and external circumstances with clarity<br />

and wisdom, and to con stantly respond<br />

to them in the best and most pro ductive<br />

way.<br />

Yet hardly a week goes by when I<br />

don’t hear about someone who has hurt<br />

themselves practicing yoga—which is<br />

odd, since asana is supposed to remedy<br />

and prevent aches and pains, not cause<br />

new ones. But the simple truth is that<br />

yoga, when performed incorrectly,<br />

can harm you.<br />

Some asana-related injuries have<br />

simple causes. A momentary lapse<br />

of attention, misjudgment about our<br />

preparedness for a particular pose or<br />

practice, or a basic misstep is sometimes<br />

all it takes. Although these injuries<br />

can set us back, they can<br />

also teach us. They can help our practice<br />

evolve by providing invaluable<br />

feed back about how we should (and<br />

shouldn’t) practice.<br />

A more subtle type of injury occurs<br />

when we choose to ignore pain, or practice<br />

through an injury. Injuries of this<br />

type occur as we repetitively practice<br />

in ways that are either uninformed or<br />

inappropriate. They often do the most<br />

long-term harm. But here’s the good<br />

news: they are also the most preventable.<br />

Almost any pose, if performed<br />

in correctly enough times, can cause<br />

problems. Urdhva mukha shvanasana—<br />

a powerful, exhilarating backbend<br />

that is part of many, if not most, yoga<br />

classes—is, I believe, a major contributor<br />

to the increasing number of<br />

lower back injuries occurring in yoga<br />

classes today. The source of the injury,<br />

however, may have less to do with the<br />

backbend itself than with the way we<br />

are practicing it.

Safe and effective asana practice is a<br />

tapestry woven with two vital threads.<br />

The first is correct mechanics, including<br />

proper alignment. The second relates to<br />

how those mechanics are applied. This<br />

involves both the attitude we bring to<br />

our practice and vinyasa karma (“wise<br />

progression,” or proper sequencing).<br />

Sequencing determines our overall experience<br />

of a given practice, as well as the<br />

extent to which our practice addresses (or<br />

neglects) our individual needs and capacities.<br />

Vinyasa karma is critical because it<br />

shapes not only the overall effectiveness<br />

of our practice, but also its impact on our<br />

long-term health.<br />

Upward-facing dog benefits us on<br />

many levels. It strengthens the arms<br />

and legs. As it stretches the front of the<br />

body (hip flexors, abdomen, and chest),<br />

the pose dramatically increases the curve<br />

in the lumbar spine, tonifying and stimulating<br />

both the kidneys and adrenals.<br />

It is mentally expansive and invigorating;<br />

it increases self-confidence and aspiration.<br />

And because upward-facing dog activates<br />

many of the qualities and energies<br />

we need to meet the demands<br />

of our fast-paced lives, it’s no wonder<br />

that it is a common denominator in so<br />

many classes.<br />

Upward-facing dog is a part of several<br />

different forms of the sun salutation,<br />

making it common for it to be the fourth<br />

pose we do in a class. For many backs<br />

that’s very little preparation for a fairly<br />

deep backbend. Along with adho mukha<br />

shvanasana (downward-facing dog) and<br />

chaturanga dandasana (four-limbed staff<br />

pose), it is also often used as a dynamic<br />

transition linking other postures, which<br />

means that upward-facing dog can be<br />

repeated many times in a single class.<br />

Unless students stay mindful, the speed<br />

and frequency of these transitions can<br />

make their lower backs vulnerable to<br />

compression.<br />

Rod Stryker has taught tantra, meditation, and<br />

hatha yoga for more than 25 years. He is an initiate<br />

and teacher in the tradition of the Himalayan masters.<br />

For more information, visit pureyoga.com.<br />

WARRIOR I (virabhadrasana I)<br />

is the standing prototype for backbends.<br />

Work the outer edge of the back foot<br />

toward the floor; internally rotate the<br />

back thigh; and draw the tailbone down<br />

into the body, as you lift the kidneys<br />

and inner ribs.<br />

Hint: Inhale, increase the buoyancy<br />

of the upper body. Exhale, expand the<br />

kidneys and flatten the lower back.<br />

1<br />

3<br />

LOCUST VARIATION (shalabhasana) As you lift the legs and<br />

the chest, draw the tailbone into the body. Gradually work the<br />

legs together and squeeze the upper arms toward each other.<br />

Keep the back of the neck long. Hold for 5 to 10 breaths.<br />

Hint: Internally rotate the thighs. Inhale, lift the torso. Exhale,<br />

lift the inner thighs.

FOUR-LIMBED STAFF POSE (chaturanga dandasana)<br />

establishes correct leg action and builds upper body strength.<br />

Place the feet 4 to 6 inches apart; powerfully draw the shins in.<br />

Engage the inner thighs and lift them toward the sky. Point the<br />

tailbone toward the heels. Lengthen the heels away from the top<br />

of the head. Gradually bring the forearms and upper arms to a<br />

90-degree angle. Hold for 5 to 10 breaths.<br />

Variation: Hold with the elbows straight.<br />

2<br />

4<br />

BOW POSE (dharanasana) Move as high as you comfortably<br />

can into the pose; then press the shinbones back. At<br />

the same time, press the breastbone forward.<br />

Hint: Inhale, enliven the chest. Exhale, draw the tailbone<br />

into the body and move higher into the pose.<br />

The primary focal point of upwardfacing<br />

dog is the lumbar spine—the least<br />

stable part of the spine and the location<br />

for the vast majority of back problems.<br />

This asana particularly stresses the<br />

junction where the sacrum and lumbar<br />

spine meet. To be able to fully explore<br />

the pose while minimizing our chances<br />

for injury, we should prepare for it by<br />

doing the following:<br />

• Building stability in the spine.<br />

• Creating more vertebral space in the<br />

lower back.<br />

• Performing poses that gradually<br />

increase the lumbar curve.<br />

• Using simpler poses that establish similar<br />

action required to do the finished<br />

pose safely.<br />

The way I avoid potential problems<br />

associated with upward-facing dog is to<br />

treat it as a deep backbend instead of as<br />

a warm-up pose. This means I often<br />

sequence it later in the class, and teach<br />

postures to prepare for sun salutations.<br />

After the body has been sufficiently<br />

pre pared, I use poses (like those pictured<br />

here) to stretch the hip flexors, chest, and<br />

abdomen; to draw the tailbone down and<br />

in toward the body; and finally to engage<br />

the arms, legs, and erector spinae muscles<br />

before doing the final pose. If you’ve<br />

properly prepared for it, upward-facing<br />

dog can be held for 10 or more breaths,<br />

allowing you to fully exalt in it and relish<br />

all that this majestic pose has to offer.<br />

(A complete practice should also include<br />

poses that expand the waist and chest<br />

and appropriate counterposes.)<br />

Yoga, by definition, is holistic—it<br />

must simultaneously address the needs<br />

of the body, mind, and soul. As soon<br />

as our hatha practice fails to do so (or<br />

worse, when it begins to impair or limit<br />

our ability to thrive), then we have lost<br />

our link to the spirit of yoga. Sometimes,<br />

retaining the “yoga” (read: “thriving”)<br />

in our practice requires only minor<br />

adjustments. Applying these refinements<br />

is a yoga in itself, one that becomes the<br />

ongoing basis for discovering a lifetime<br />

of freedom and joy.

Revolved Head-to-Knee Pose<br />

(Parivritta Janu Shirshasana)<br />

“How will I ever master that pose?” Anyone who has practiced yoga has<br />

asked themselves a similar question one time or another. I recall two occasions,<br />

both of which occurred in my 20s when I<br />

was at the height of my flexibility. The first<br />

was at a performance of Cirque du Soleil.<br />

The second was watching a contortionist on<br />

the boardwalk in Venice, California. Despite<br />

the number of advanced postures I could do,<br />

I felt a kind of hopelessness about the future<br />

of my asana practice on both occasions. If<br />

you’ve seen someone do something with<br />

their body that seemed utterly out of reach,<br />

you may have had similar doubts about your<br />

ability to attain mastery. These doubts compel<br />

us to examine the relationship between<br />

mastery of asana and extreme flexibility and/<br />

or strength. Before we assume we’ll never<br />

attain mastery in asana, let’s look at what it<br />

really means.<br />

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra is the most illuminating<br />

text on the science of yoga. Revered<br />

through the ages, its sublime and comprehensive<br />

teachings are contained in 196 aphorisms.<br />

Asana is only mentioned in four, a fact<br />

which sheds light on the place of the poses in<br />

the larger context of yoga.<br />

Asana is first mentioned early in the<br />

second chapter as one of the eight limbs<br />

of ashtanga yoga. The last mentions are in<br />

sutras 2.46–48, where we find the teaching<br />

on its practice. Sutra 2.46 offers a basic<br />

definition and practice guidelines: “Asana<br />

is a steady or motionless (sthira) posture<br />

accompanied with a sense of ease or comfort<br />

(sukha).” But it is the last two sutras that<br />

address our question about mastery. Here<br />

Patanjali is crystal clear: while doing your<br />

asana (with sukha and sthira), “loosen effort<br />

while meditating on the Infinite (ananta).”<br />

That’s it. There is no mention of<br />

becoming a master once you can, say, put<br />

your leg behind your head. Mastery doesn’t<br />

depend on feats of flexibility or strength<br />

but is sourced through communion with<br />

the Infinite.<br />

Awareness of the Infinite is unquestionably<br />

a state of mind, yet certain postures<br />

more readily open the door. Some of the<br />

most direct are lateral poses—parivritta<br />

janu shirshasana chief among them. This<br />

powerful, radiant pose delivers an immediate<br />

>><br />

experience of the boundless.

{ the art of asana }<br />

Revolved head-to-knee pose generates an experience of freedom and ease, awakening<br />

a sense of the boundlessness of our true nature.

What does it mean to be boundless physically?<br />

The answer may surprise you: bodiless.<br />

That’s right—the culmination of asana is to<br />

no longer identify with your body. This idea is<br />

not as lofty as it may sound. In fact, it’s something<br />

we all aspire to. It’s called being healthy.<br />

Nothing reminds us more of having a body<br />

than physical suffering—the tiniest splinter<br />

brings us right back to our mortal coil. On<br />

the other hand, when nothing ails us we live<br />

joyously and spontaneously, even spaciously,<br />

unaware of the container called “my body.”<br />

Therein lies one of the great paradoxes<br />

of yoga practice. The ultimate achievement<br />

in asana is to experience the Infinite—“no<br />

body.” Yet the very process of working on the<br />

body day after day to build physical precision<br />

and control often makes us more absorbed<br />

in it. That is the risk of seeing asana as a predominantly<br />

physical practice. The more we do<br />

it, the more absorbed we become in the very<br />

thing we are meant to move beyond.<br />

So how does one get beyond the body?<br />

The answer, at least through asana, lies in the<br />

postures that move energy up—namely, backbends<br />

and laterals. Lateral postures are particularly<br />

effective. While elongating the spine,<br />

they create space in the intercostal, quadratus,<br />

adductor, shoulder, and abdominal muscles,<br />

as well as in the pelvis, lungs, and heart. They<br />

also stretch the kidneys, which, according to<br />

the Taoist tradition, frees stagnant energies<br />

that settle there as a direct result of unresolved<br />

fear. Finally, at the pranic level, laterals<br />

increase both prana and vyana, which activate<br />

the qualities of lightness and ascension.<br />

The postures on these pages illustrate—<br />

with one exception—the main types of laterals:<br />

standing, open frame (arm balance),<br />

kneeling, and sitting (the “apex” pose on<br />

the previous page). The supine open-frame<br />

type is not pictured. The five poses here are<br />

sequenced to provide maximum preparation<br />

for parivritta janu shirshasana, the apex pose<br />

of the sequence. A complete lateral practice<br />

should also include sun salutations, additional<br />

standing, sitting, and lying postures that have<br />

a backbend emphasis, as well as the appropriate<br />

counterposes.<br />

The key to effective and safe lateral stretch-<br />

Rod Stryker has taught tantra, meditation, and hatha<br />

yoga for more than 25 years. He is an initiate and teacher<br />

in the tradition of the Himalayan masters. For more<br />

information, visit pureyoga.com.<br />

TRIANGLE POSE VARIATION (trikonasana) prepares us for the deeper laterals.<br />

Grounds the legs to help anchor the hips. Emphasizes the extension of the<br />

waist and the spine—not the shoulder. The back body is on the same plane as<br />

the backs of the legs; the shoulders stack. Draw the top arm into the shoulder<br />

and activate the inner body to reach toward the top of the head.<br />

Hint: Inhale, the spine lengthens. Exhale, move the navel toward the spine while<br />

rotating the chest toward the sky.<br />

1<br />

VASISTHASANA III is a classic lateral arm<br />

balance. Shins in, shoulders stack. Lift and<br />

press the inner thighs back while hugging<br />

the sacrum into the body.<br />

Hint: Inhale, broaden the collarbones while<br />

drawing the waist and the ribs away from the<br />

hips. Exhale, the navel rotates toward the sky.<br />

3

STANDING HAND-TO-TOE POSE<br />

(utthita hasta padangushthasana)<br />

is an adductor stretch that activates<br />

the secondary action of the<br />

laterals. Press into both heels.<br />

Both sides of the waist lift. While<br />

pressing the inner thigh of the<br />

lifted leg forward, rotate the torso<br />

in the opposite direction.<br />

Hint: Inhale, expand the back body.<br />

Exhale, stabilize the standing leg<br />

and the sacrum.<br />

2<br />

ing is stabilizing the hips and then, while<br />

rotating the torso, maintaining length in the<br />

spine. Avoid overarching the lower back,<br />

collapsing the chest, or insufficient rotation.<br />

Proper alignment and maintaining a balance<br />

among stability, rotation, and elongation<br />

allow us to create a deep and dynamic<br />

lateral stretch. If necessary, go halfway in<br />

any or all of the postures in order to maintain<br />

that specific intention and to get the<br />

most benefit.<br />

What is the result of doing asana masterfully?<br />

Patanjali mentions nothing about<br />

physical accomplishment. According to<br />

yoga’s greatest sage, the culmination of<br />

asana is that duality (good/bad, happiness/<br />

disappointment, success/failure) no longer<br />

affects us. Asana done in the right spirit<br />

leads to being less and less at the mercy of<br />

the ups and downs of everyday life. Thus,<br />

the ultimate achievement in asana is boundless<br />

freedom—a state of being so present<br />

and at ease with who we are that we are able<br />

to masterfully shape destiny itself.<br />

LATCH POSE (parighasana) is deepened by<br />

emphasizing its asymmetrical component. To<br />

do this, expand the upper-side body (i.e., arch<br />

the upper-side waist, the intercostals, and the<br />

lung toward the sky).<br />

Hint: Inhale, lengthen the side, the back, and the<br />

front bodies. Exhale, draw the tailbone into the<br />

body, applying enough rotation so that the shoulders<br />

are stacked.<br />

HEAD-TO-KNEE POSE (janu shirshasana)<br />

stretches the back for the sitting twist: parivritta<br />

janu shirshasana. Press the inner thigh toward<br />

the floor and the extended heel forward. Externally<br />

rotate the inner thigh of the bent knee—<br />

gradually working that knee away from the<br />

straight leg. Elongate both sides of the waist.<br />

Hint: Inhale, lengthen the sides and lift the collarbones.<br />

Exhale, flatten the lower back.<br />

4 5

{ the art of asana }<br />

Maha mudra challenges us to master our vital energy, which is the real key to deepening the practice of yoga.<br />

Here is a sequence that will prepare you for the physical mechanics of the pose… and its subtler dimensions.

Great Seal<br />

(Maha Mudra)<br />

Yoga has changed. Have you noticed? During my three decades of teaching<br />

I have watched the yoga that we practice in the West become physically<br />

harder and harder. On one hand, that’s positive. It means that while many<br />

of us are seizing the opportunity to challenge<br />

ourselves, we are also enjoying the benefits<br />

of one of the most complete and effective<br />

forms of exercise ever developed. On the<br />

other hand, it causes us to make assumptions<br />

about yoga that are simply inaccurate.<br />

We assume that the more we advance in<br />

our practice, the more vigorous and complicated<br />

it should be. Accomplished practitioners<br />

are expected to relish physical intensity,<br />

but according to yogic adepts, just the opposite<br />

is true. As practice evolves it becomes<br />

less, not more, physical. True adepts require<br />

less and less effort to attain the higher states<br />

of yoga. From their perspective, the most<br />

profound practices are ones that provide<br />

access to the subtlest dimensions of the self.<br />

Compared to asana, these methods link us<br />

more directly to yoga’s ultimate goal—selfrealization.<br />

What are these techniques, and<br />

how are they organized?<br />

Classic texts describe four practices—<br />

asana, bandha, pranayama, and mudra—that<br />

are arranged in a hierarchy; each builds on<br />

the ones before it. Asanas (postures) steady<br />

the body and mind, preparing them for<br />

deeper practices; bandhas (locks) help us<br />

retain vital energy; pranayama techniques<br />

(breathing practices) build and regulate<br />

energy; and mudras (subtle techniques of<br />

internal control) allow us to direct and channel<br />

it. Together, these techniques create an<br />

internal alchemy—a transformation affecting<br />

every level of the self.<br />

Among the most revered of these methods<br />

is maha mudra. Like other mudras, it is<br />

a practice that arranges the body so that its<br />

outward form (its “gesture or attitude”—<br />

literal meanings of the word mudra) contributes<br />

to the awakening of a new spiritual perspective.<br />

Inwardly, maha mudra combines<br />

asana, bandha, and pranayama to create a<br />

kind of seal (yet another meaning), preventing<br />

internal energies from being dissipated.<br />

By both activating the body’s subtle forces<br />

and teaching us how to contain them, maha<br />

mudra quietly deepens concentration and<br />

creates a powerful bridge between body,<br />

mind, and spirit.

HALF LATERAL BEND (ardha parshvottanasana)<br />

strengthens the lower back and elongates the spine. The<br />

front knee is slightly flexed. Move in and out of the pose<br />

5 times (exhale into the pose, fold, inhale up). Then hold<br />

for 5 breaths.<br />

Variation: Do with both arms by your side.<br />

Hint: Begin your inhalation by filling the<br />

chest and upper back. Begin your<br />

exhalation by contracting the abdomen.<br />

ROTATED TRIANGLE (parivritta<br />

trikonasana) frees the hips and<br />

initiates the twisting motion of<br />

maha mudra. Keep the feet<br />

parallel and the back leg straight.<br />

Variation: Bend the front knee.<br />

Hint: Exhale, contract the navel,<br />

and rotate toward the sky.<br />

1 2<br />

EMPTY LAKEBED SEAL (tadaka<br />

mudra) The legs and the spine<br />

stretch in opposite directions.<br />

Take slow, complete breaths.<br />

Engage the root and chin locks.<br />

If comfortable, pause after exhalation<br />

and draw the abdomen<br />

back and up. Hold tadaka mudra<br />

for 1–5 minutes.<br />

Hint: Relax the abdomen before<br />

inhaling. Maintain the root lock<br />

throughout.<br />

ABDOMINAL LIFT (uddiyana bandha)<br />

While exhaling, contract the abdomen toward the<br />

spine. Expel the rest of the air through the mouth.<br />

Hold the breath out and slowly draw the<br />

internal organs back and up. Release<br />

the abdomen slowly before inhaling.<br />

Hint: Lower your chin to avoid<br />

discomfort in the throat.<br />

4a<br />

4b

BRIDGE POSE (setu bandhasana<br />

sarvangasana) elongates the<br />

upper spine and develops the<br />

openness in the chest that is<br />

necessary for the chin lock. The<br />

chest opens expansively while the<br />

mind rests. The base of the neck<br />

is off the floor.<br />

Hint: Press your outer upper<br />

arms into the floor.<br />

3<br />

THREE-ANGLED LEG-FACING FORWARD BEND<br />

(trianga mukhaikapada pashchimottanasana) increases<br />

the flexibility of the legs and the lower back. The knees<br />

should be two or three inches apart. Internally rotate<br />

both thighs. Keep the spine straight. The shoulder<br />

blades slide down the back.<br />

Variation: Sit on folded blankets to help with tight<br />

hamstrings.<br />

Hint: Avoid rounding the spine. Inhale, create more<br />

length. Exhale, flatten the lower back.<br />

5<br />

At first glance, maha mudra (literally, the “great<br />

seal”) looks much like any other pose. But a closer<br />

inspection reveals why it is so profound: it integrates<br />

many levels of the self. Physically, it challenges us to<br />

bend forward from the hip joints, not the lower back.<br />

This means keeping the spine aligned and the torso<br />

elongated through the crown of the head.<br />

As you practice, draw the upper body back and do<br />

not allow the upper spine, neck, or shoulders to round.<br />

Counter your effort in the upper body by lengthening<br />

the back of the extended leg. This will challenge the<br />

lower back, so work slowly and do not let your back<br />

collapse. Flex the foot and reach through the heel to<br />

deepen the stretch. The combination of leg and upper<br />

body work in this mudra generates a tremendous<br />

amount of energy.<br />

Next, apply two locks: mula bandha (the root lock)<br />

and jalandhara bandha (the chin lock). To apply the<br />

root lock, contract and draw the center of the pelvic<br />

floor upward. To apply the chin lock, lengthen the<br />

back of the neck and tip the chin toward the notch<br />

below the throat. These locks act as seals, containing<br />

energy along the spinal column.<br />

Then, become aware of the flow of your breathing.<br />

Maintain the root lock while deepening and<br />

relaxing your breath. This will quiet your nervous<br />

system and provide a natural focus for your mind. In<br />

more ad vanced stages of practice, breath retention is<br />

practiced, along with a third lock, uddiyana bandha (the<br />

abdominal lift). It is essential to work with a teacher at<br />

this stage of practice. Over time, the combination of all<br />

these techniques will slowly awaken dormant energies<br />

at the base of the spine. As a result, your meditation<br />

posture improves, your concentration deepens, and<br />

you bring more spontaneity to daily life.<br />

As with any posture, you can access maha mudra<br />

more effectively with proper preparation. Create a practice<br />

sequence that prepares you both for the physical<br />

mechanics of the pose and its subtler dimensions. The<br />

techniques pictured here are ones I consistently include<br />

when I lead a class that features maha mudra. In addition<br />

to these poses, you will also want to include sun<br />

salutations and a variety of other standing, preparatory,<br />

and counter poses that elongate and stabilize the spine.<br />

I hope this will give you a glimpse of the more subtle<br />

dimensions of yoga—dimensions that you can begin<br />

to explore yourself. As the sages tell us, the body is a<br />

vessel, sustained by living energy. Learning to master<br />

that vital energy is the key to deepening our practice—<br />

and to living a more joyful life.<br />

Rod Stryker has taught tantra, meditation, and hatha yoga for more<br />

than 25 years. He is an initiate and teacher in the tradition of the<br />

Himalayan masters. For more information, visit parayoga.com.

{Art of Asana}<br />

This powerful seated twist cultivates equanimity and inner illumination—<br />

two qualities that help us unlock our vast potential and reach yoga’s ultimate aim.<br />

Bharadvaja’s Twist II<br />

(Bharadvajasana II)<br />

What should you expect from yoga? Even if you’ve never done it, you are probably familiar<br />

with its benefits: a healthier, more flexible body, reduced muscular and mental tension, improved<br />

vitality, clearer thinking, deep relaxation, and perhaps even a better, more fulfilling sex life.<br />

But before we conclude that’s all there is to yoga,<br />

let’s consider it in a larger context. Throughout the<br />

ages there have been accounts of masters who cultivated<br />

abilities most of us would describe as fantastic:<br />

the capacity to be in more than one place at the same<br />

time; to consume poison with no ill effects; to foresee<br />

the future; to materialize objects out of thin air; and<br />

even the capacity to affect fate. So…which is it? Does<br />

yoga simply offer a better quality of life or does it have<br />

the potential to expand our capacities in ways that<br />

few of us can even imagine? The answer is: both. It all<br />

depends upon what you practice and how.<br />

The ancient teachings consistently remind us that<br />

siddhis (miraculous powers) are at best distractions<br />

from the deeper purpose of life, and are not goals<br />

worth pursuing in and of themselves. Yet they can<br />

serve as beacons, reminders that hidden within each<br />

of us are great mysteries to solve and unfathomable<br />

possibilities to unlock.<br />

We all come into this world with similar faculties.<br />

Both a sage and a salesman have a mortal body,<br />

five senses, access to prana (the vital force), consciousness,<br />

and a soul. So what determines how<br />

much of our vast potential we will unlock or, more to<br />

the point, how far yoga can take us? The scriptures<br />

are very clear: The key to unlocking our infinite<br />

capacities and fulfilling yoga’s ultimate promise is<br />

the mind. More specifically, we must cultivate two of<br />

the mind’s inherent qualities: equanimity and inner<br />

illumination.<br />

The hatha yoga tradition describes specific practices<br />

that awaken dormant capacities. Yet before we<br />

tackle these advanced techniques we must be firmly<br />

rooted in qualities first cultivated through asana.<br />

Some of the most effective for increasing equanimity<br />

and inner illumination are twists, particularly when<br />

they are held for longer periods of time.<br />

Bharadvajasana II is a powerful seated twist that<br />

builds both these qualities. Like all twists, it releases<br />

contraction in musculature as well as con nective<br />

tissue, while improving visceral processes: the liver,<br />

spleen, kidneys, and particularly the digestive and<br />

eliminative functions are strengthened. At a more<br />

subtle level, twists build samana, the “equalizing<br />

force.” Stored in your abdomen, samana is one of<br />

ten types of prana in the body. Its specific role is to<br />

engender mental and physical stillness, as well as<br />

assimilative capacity. Your capacity to slow down,<br />

rest deeply, and process what you take in, is determined<br />

by your supply of samana.

According to ayurveda, assimilation is<br />

the cornerstone of physical well-being. In<br />

simple terms, assimilation is the process<br />

of transforming what we ingest into nourishment.<br />

On the mental level assimilation is<br />

the process of transforming our experiences<br />

into life lessons that nourish us and help us<br />

grow. Strong mental assimilation allows us<br />

to efficiently extract what all experience—<br />

both good and bad—is meant to teach us.<br />

As the force behind assimilation, samana<br />

is a form of subtle fire which, at the mental<br />

level, ignites our capacity to “digest” or<br />

burn our psychological patterning. As samana<br />

increases, it fuels the inner light that<br />

removes the darkness of spiritual ignorance.<br />

Twists are the most effective postures for<br />

building samana.<br />

The key to twisting is the relationship<br />

between the hips, shoulders, and head.<br />

The mechanics of a twist require us to<br />

stabilize at least one of these three areas.<br />

For example, in a lying twist the shoulders<br />

remain relatively stable, while the hips and<br />

(sometimes) the head rotate. In sitting<br />

twists we stabilize the hips while rotating<br />

the shoulders. In the case of bharadvajasana<br />

II, the head and shoulders rotate in opposite<br />

directions, while the hips remain stable.<br />

There is a natural progression to<br />

twisting that we should follow to maximize<br />

safety and effectiveness. In general, proceed<br />

from standing, to lying, to seated twists.<br />

The last of these are “fixed”—in other<br />

words, the hips are immobilized. Seated,<br />

fixed twists are the most powerful and<br />

require the greatest amount of preparation<br />

and caution.<br />

The focal points that facilitate twisting<br />

are flexibility and/or stability in the hips,<br />

shoulders, and neck. The postures pictured<br />

here address most of these focal points.<br />

They should be part of a complete prac -<br />

tice that includes sun salutations, standing<br />

postures that emphasize hamstring<br />

and hip flexibility, at least one or two lying<br />

twists, and counterposes. Since twists are<br />

asym metrical (one side is doing something<br />

SPREAD-LEGGED STANDING FORWARD BEND (prasarita<br />

padottanasana) affects flexibility in hips and hamstrings, increas -<br />

ing our ease in twists. Rotate thighs internally, inner arches lift.<br />

Soften the space between the shoulder blades, release them down<br />

the back.<br />

Hint: On inhale, lengthen the front body and spine. On exhale,<br />

abdomen softly contracts. Soften the spine and upper body deeper<br />

into the pose.<br />

1<br />

HALF-BOUND STANDING FORWARD BEND (ardha baddha<br />

padottanasana) can be done with both hands on the floor. Slightly<br />

flex the standing knee, if necessary, to avoid hyperextension.<br />

Draw standing shin in to balance the weight on the standing foot.<br />

Hint: Exhale, flatten lower back, releasing contraction in hamstring,<br />

hips, and back. Draw shoulders away from ears, keep neck long, base<br />

of the skull floats.<br />

Rod Stryker has taught tantra, meditation, and hatha<br />

yoga for more than 25 years. He is an initiate and<br />

teacher in the tradition of the Himalayan masters.<br />

For more information, visit pureyoga.com.<br />

3

REVOLVED TRIANGLE (parivritta trikonasana)<br />

is deepened when the hips are stable.<br />

While sacrum remains parallel to the floor<br />

shoulders rotate. Navel initiates the action<br />

of the twist. Draw shins in. Inner thighs<br />

lift and move back.<br />

Hint: Inhale, lengthen spine, broaden the<br />

collarbones. Exhale, navel moves into the<br />

body and twists toward the sky.<br />

2<br />

different than the other), symmetrical forward<br />

bends are ideal counter poses. Twists<br />

are contra-indicated for serious disc issues.<br />

Those with excessive thoracic curvature or<br />

very tight hips should either avoid seated<br />

twists or practice them cautiously. Finally,<br />

it is important to ground the sacrum and<br />

engage the inner thighs in all twists in order<br />

to maintain and even increase lower back<br />

stability.<br />

As with all poses the deeper effects of<br />

twisting unfold during longer holds. A<br />

min imum of one to two minutes in the<br />

pose is required before subtle forces are<br />

signifi cantly affected. At the same time,<br />

longer holds challenge us to steady our<br />

mind, providing an opportunity to mentally<br />

cul tivate pranic force. This yogic approach<br />

to twisting—with mind, body, and breath<br />

synergistically engaged—enlivens us with<br />

balance, ease, and the subtle force of inner<br />

fire. Once established in these qualities we<br />

can dissolve our impediments to a fully<br />

illumined life and thus set the stage to<br />

realize ourselves, which is yoga’s boundless<br />

promise.<br />

ROTATED HERO (parivritta virasana) opens quadriceps<br />

and ankles for bharadvajasana II. With hips fixed,<br />

emphasize navel center as the source of rotation.<br />

Hint: Inhale, elongate spine, lift collarbones. Exhale, draw<br />

tailbone into the body, navel toward spine, and deepen the<br />

rotation of the shoulders.<br />

HALF-SEATED SPINAL TWIST (ardha matsyendrasana)<br />

variations include straightening knee on the floor,<br />

back hand can wrap or bind. Increases the rotational<br />

flexibility of the spine, inner body, and hips.<br />

Hint: When twisting to the left, spread right side of the<br />

back away from the spine. Inhale, lengthen. Exhale,<br />

contract abdomen to deepen the twist.<br />

4<br />

5

presents<br />

the Art of Asana Master Class series.<br />

In the first of its master class series, Yoga International has teamed<br />

up with Rod Stryker, the founder of ParaYoga, to help readers apply the<br />

timeless teachings of yoga to their daily practice. Rod Stryker is widely<br />

considered to be one of the preeminent yoga and meditation teachers in<br />

the United States. He is renowned for his depth of knowledge, practical<br />

wisdom, and unique ability to transmit the deepest aspect of the teachings<br />

and practices to modern audiences and students from all walks of life. Rod<br />

has taught for more than 30 years, training teachers and leading corporate<br />

seminars, yoga retreats, and workshops throughout the world.<br />

For more ways to deepen your practice, log on to yogainternational.com.<br />

For information about Rod Stryker and ParaYoga, visit parayoga.com<br />

©2012 by the Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the USA. All rights reserved.<br />

Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without permission is prohibited.<br />

All photographs © Lois Greenfield; Used with permission; all rights reserved.