A Time for Old Men - Winston Churchill

A Time for Old Men - Winston Churchill

A Time for Old Men - Winston Churchill

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

“A <strong>Time</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>Old</strong> <strong>Men</strong>”<br />

THE JOURNAL OF WINSTON CHURCHILL<br />

SPRING 2011 • NUMBER 150<br />

$9.95 / £6.50

i<br />

THE CHURCHILL CENTRE & CHURCHILL WAR ROOMS<br />

UNITED STATES • CANADA • UNITED KINGDOM • AUSTRALIA • PORTUGAL<br />

PATRON: THE LADY SOAMES LG DBE • WWW.WINSTONCHURCHILL.ORG<br />

Founded in 1968 to educate new generations about the<br />

leadership, statesmanship, vision and courage of <strong>Winston</strong> Spencer <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

® ®<br />

MEMBER, NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR HISTORY EDUCATION • RELATED GROUP, AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION<br />

SUCCESSOR TO THE WINSTON S. CHURCHILL STUDY UNIT (1968) AND INTERNATIONAL CHURCHILL SOCIETY (1971)<br />

BUSINESS OFFICES<br />

200 West Madison Street<br />

Suite 1700, Chicago IL 60606<br />

Tel. (888) WSC-1874 • Fax (312) 658-6088<br />

info@winstonchurchill.org<br />

CHURCHILL MUSEUM<br />

AT THE CHURCHILL WAR ROOMS<br />

King Charles Street, London SW1A 2AQ<br />

Tel. (0207) 766-0122 • http://cwr.iwm.org.uk/<br />

CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD<br />

Laurence S. Geller<br />

lgeller@winstonchurchill.org<br />

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR<br />

Lee Pollock<br />

lpollock@winstonchurchill.org<br />

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER<br />

Daniel N. Myers<br />

dmyers@winstonchurchill.org<br />

DIRECTOR OF ADMINISTRATION<br />

Mary Paxson<br />

mpaxson@winstonchurchill.org<br />

BOARD OF TRUSTEES<br />

The Hon. Spencer Abraham • Randy Barber<br />

Gregg Berman • David Boler • Paul Brubaker<br />

Donald W. Carlson • Randolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

David Coffer • Manus Cooney Lester Crown<br />

Sen. Richard J. Durbin • Kenneth Fisher •<br />

Laurence S. Geller • Rt Hon Sir Martin Gilbert CBE<br />

Richard C. Godfrey • Philip Gordon • D. Craig Horn<br />

Gretchen Kimball • Richard M. Langworth CBE<br />

Diane Lees • Peter Lowy<br />

Rt Hon Sir John Major KG CH • Lord Marland<br />

J.W. Marriott Jr. • Christopher Matthews<br />

Sir Deryck Maughan • Harry E. McKillop • Jon Meacham<br />

Michael W. Michelson • John David Olsen • Bob Pierce<br />

Joseph J. Plumeri • Lee Pollock • Robert O’Brien<br />

Philip H. Reed OBE • Mitchell Reiss • Ken Rendell<br />

Elihu Rose • Stephen Rubin OBE<br />

The Hon. Celia Sandys • The Hon. Edwina Sandys<br />

Sir John Scarlett KCMG OBE<br />

Sir Nigel Sheinwald KCMG • Mick Scully<br />

Cita Stelzer • Ambassador Robert Tuttle<br />

HONORARY MEMBERS<br />

Rt Hon David Cameron, MP<br />

Rt Hon Sir Martin Gilbert CBE<br />

Robert Hardy CBE<br />

The Lord Heseltine CH PC<br />

The Duke of Marlborough JP DL<br />

Sir Anthony Montague Browne KCMG CBE DFC<br />

Gen. Colin L. Powell KCB<br />

Amb. Paul H. Robinson, Jr.<br />

The Lady Thatcher LG OM PC FRS<br />

FRATERNAL ORGANIZATIONS<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> Archives Centre, Cambridge<br />

The <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> Memorial Trust, UK, Australia<br />

Harrow School, Harrow-on-the-Hill, Middlesex<br />

America’s National <strong>Churchill</strong> Museum, Fulton, Mo.<br />

COMMUNICATIONS<br />

John David Olsen, Director and Webmaster<br />

Chatlist Moderators: Jonah Triebwasser, Todd Ronnei<br />

http://groups.google.com/group/<strong>Churchill</strong>Chat<br />

Twitter: http://twitter.com/<strong>Churchill</strong>Centre<br />

ACADEMIC ADVISERS<br />

Prof. James W. Muller,<br />

Chairman, afjwm@uaa.alaska.edu<br />

University of Alaska, Anchorage<br />

Prof. Paul K. Alkon, University of Southern Cali<strong>for</strong>nia<br />

Rt Hon Sir Martin Gilbert CBE, Merton College, Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Col. David Jablonsky, U.S. Army War College<br />

Prof. Warren F. Kimball, Rutgers University<br />

Prof. John Maurer, U.S. Naval War College<br />

Prof. David Reynolds FBA, Christ’s College, Cambridge<br />

Dr. Jeffrey Wallin,<br />

American Academy of Liberal Education<br />

LEADERSHIP & SUPPORT<br />

NUMBER TEN CLUB<br />

Contributors of $10,000+ per year<br />

Skaddan Arps • Boies, Schiller & Flexner LLP<br />

Carolyn & Paul Brubaker • Mrs. <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Lester Crown • Kenneth Fisher • Marcus & Molly Frost<br />

Laurence S. Geller • Rick Godfrey • Philip Gordon<br />

Martin & Audrey Gruss • J.S. Kaplan Foundation<br />

Gretchen Kimball • Susan Lloyd • Sir Deryck Maughan<br />

Harry McKillop • Elihu Rose • Michael Rose<br />

Stephen Rubin • Mick Scully • Cita Stelzer<br />

CHURCHILL CENTRE ASSOCIATES<br />

Contributors to The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre Endowment, of<br />

$10,000, $25,000 and $50,000+, inclusive of bequests.<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> Associates<br />

The Annenberg Foundation • David & Diane Boler<br />

Samuel D. Dodson • Fred Farrow • Marcus & Molly Frost<br />

Mr. & Mrs. Parker Lee III • Michael & Carol Mc<strong>Men</strong>amin<br />

David & Carole Noss • Ray & Patricia Orban<br />

Wendy Russell Reves • Elizabeth <strong>Churchill</strong> Snell<br />

Mr. & Mrs. Matthew Wills • Alex M. Worth Jr.<br />

Clementine <strong>Churchill</strong> Associates<br />

Ronald D. Abramson • <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Jeanette & Angelo Gabriel• Craig & Lorraine Horn<br />

James F. Lane • John Mather • Linda & Charles Platt<br />

Ambassador & Mrs. Paul H. Robinson Jr.<br />

James R. & Lucille I. Thomas • Peter J. Travers<br />

Mary Soames Associates<br />

Dr. & Mrs. John V. Banta • Solveig & Randy Barber<br />

Gary & Beverly Bonine • Susan & Daniel Borinsky<br />

Nancy Bowers • Lois Brown<br />

Carolyn & Paul Brubaker • Nancy H. Canary<br />

Dona & Bob Dales • Jeffrey & Karen De Haan<br />

Gary Garrison • Ruth & Laurence Geller<br />

Fred & Martha Hardman • Leo Hindery, Jr.<br />

Bill & Virginia Ives • J. Willis Johnson<br />

Jerry & Judy Kambestad • Elaine Kendall<br />

David M. & Barbara A. Kirr<br />

Barbara & Richard Langworth • Phillip & Susan Larson<br />

Ruth J. Lavine • Mr. & Mrs. Richard A. Leahy<br />

Philip & Carole Lyons • Richard & Susan Mastio<br />

Cyril & Harriet Mazansky • Michael W. Michelson<br />

James & Judith Muller • Wendell & Martina Musser<br />

Bond Nichols • Earl & Charlotte Nicholson<br />

Bob & Sandy Odell • Dr. & Mrs. Malcolm Page<br />

Ruth & John Plumpton • Hon. Douglas S. Russell<br />

Daniel & Suzanne Sigman • Shanin Specter<br />

Robert M. Stephenson • Richard & Jenny Streiff<br />

Gabriel Urwitz • Damon Wells Jr.<br />

Jacqueline Dean Witter<br />

ALLIED NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS<br />

_____________________________________<br />

INTL. CHURCHILL SOCIETY CANADA<br />

14 Honeybourne Crescent, Markham ON, L3P 1P3<br />

Tel. (905) 201-6687<br />

www.winstonchurchillcanada.ca<br />

Ambassador Kenneth W. Taylor, Honorary Chairman<br />

CHAIRMAN<br />

Randy Barber, randybarber@sympatico.ca<br />

VICE-CHAIRMAN AND RECORDING SECRETARY<br />

Terry Reardon, reardont@rogers.com<br />

TREASURER<br />

Barrie Montague, bmontague@cogeco.ca<br />

BOARD OF DIRECTORS<br />

Charles Anderson • Randy Barber • David Brady<br />

Peter Campbell • Dave Dean • Cliff Goldfarb<br />

Robert Jarvis • Barrie Montague • Franklin Moskoff<br />

Terry Reardon • Gordon Walker<br />

_____________________________________<br />

INTL. CHURCHILL SOCIETY PORTUGAL<br />

João Carlos Espada, President<br />

Universidade Católica Portuguesa<br />

Palma de Cima 1649-023, Lisbon<br />

jespada@iep.ucp.pt • Tel. (351) 21 7214129<br />

__________________________________<br />

THE CHURCHILL CENTRE AUSTRALIA<br />

Alfred James, President<br />

65 Billyard Avenue, Wahroonga, NSW 2076<br />

abmjames1@optusnet.com.au • Tel. 61-2-9489-1158<br />

___________________________________________<br />

THE CHURCHILL CENTRE - UNITED KINGDOM<br />

Allen Packwood, Executive Director<br />

c/o <strong>Churchill</strong> Archives Centre<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> College, Cambridge, CB3 0DS (allen.packwood@chu.cam.ac.uk<br />

• Tel. (01223) 336175<br />

TRUSTEES<br />

The Hon. Celia Sandys, Chairman<br />

David Boler • Randolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong> • David Coffer<br />

Paul H. Courtenay • Laurence Geller • Philip Gordon<br />

Scott Johnson • The Duke of Marlborough JP DL<br />

The Lord Marland •<br />

Philippa Rawlinson • Philip H. Reed OBE<br />

Stephen Rubin OBE • Anthony Woodhead CBE FCA<br />

SECRETARY TO THE TRUSTEES<br />

John Hirst<br />

HON. MEMBERS EMERITI<br />

Nigel Knocker OBE • David Porter<br />

___________________________________________<br />

THE CHURCHILL CENTRE - UNITED STATES<br />

D. Craig Horn, President<br />

5909 Bluebird Hill Lane<br />

Weddington, NC 28104<br />

dcraighorn@carolina.rr.com • Tel. (704) 844-9960<br />

________________________________________________<br />

THE CHURCHILL SOCIETY FOR THE ADVANCE-<br />

MENT OF PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRACY<br />

www.churchillsociety.org<br />

Robert A. O’Brien, Chairman<br />

3050 Yonge Street, Suite 206F<br />

Toronto ON, M4N 2K4

CONTENTS<br />

The Journal of<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

,<br />

Number 150<br />

Spring 2011<br />

Alkon, 16<br />

Reardon, 20<br />

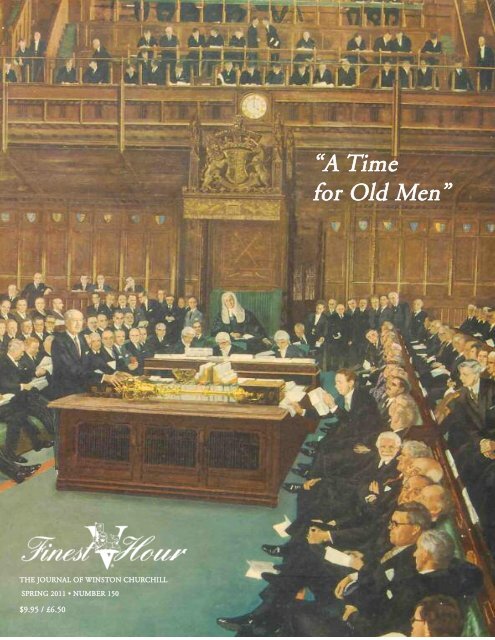

COVER<br />

“The Debate on the Address, House of Commons, 1 November 1960,” by Alfred R. Thomson RA.<br />

Sir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> (back cover) is in his usual seat below the gangway. Prime Minister Harold<br />

Macmillan is speaking. Seated behind him (red hair) is Commonwealth Secretary Duncan Sandys.<br />

To Sandys’ right are Henry Brooke and (back cover) Selwyn Lloyd, R.A. Butler and, probably, John<br />

Maclay. Behind Maclay, leaning <strong>for</strong>ward with paper in hand, is the Prime Minister’s son Maurice.<br />

Facing Macmillan, leaning <strong>for</strong>ward with paper in hand, is the Leader of the Opposition, Labour’s<br />

Hugh Gaitskell; behind him, also leaning, is Liberal Leader Jo Grimond. The painting, presented to<br />

Harold Macmillan by the 1922 Committee in 1963, hangs in the Palace of Westminster.<br />

ARTICLES<br />

Theme of the Issue: “A <strong>Time</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Old</strong> <strong>Men</strong>”<br />

10/ Introduction: Age and Leadership • Richard M. Langworth<br />

11/ May 1940: A <strong>Time</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Old</strong> <strong>Men</strong> • Don C. Graeter<br />

16/ <strong>Churchill</strong> on Clemenceau: His Best Student? Part I • Paul Alkon<br />

20/ The Reluctant Retiree: Did <strong>Churchill</strong> Stay Too Long? • Terry Reardon<br />

25/ Holding Fast: <strong>Churchill</strong>’s Longevity • John H. Mather M.D.<br />

26/ The Lion in Winter: Encounters with <strong>Churchill</strong> 1946-1962 • Dana Cook<br />

31/ Confronting Television in <strong>Old</strong> Age • The Editors<br />

32/ <strong>Churchill</strong> Defiant: Barbara Leaming’s Brilliant Insights • Richard M. Langworth<br />

k k k<br />

34/ “Anarchism and Fire”: What We Can Learn from Sidney Street • Christopher C. Harmon<br />

36/ “Golden Eggs,” Part II: Intelligence and the Eastern Front • Martin Gilbert<br />

43/ On Russia • <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

CHURCHILL PROCEEDINGS<br />

58/ Great Contemporaries: Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher • Barry Gough<br />

Leaming, 32<br />

Gough, 58<br />

BOOKS, ARTS & CURIOSITIES<br />

44/ The King’s Speech, by David Seidler • David Freeman<br />

45/ Christian Encounters: <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>, by John Perry • Ted Hutchinson<br />

46/ The De Valera Deception, by Michael & Patrick Mc<strong>Men</strong>amin • David Freeman<br />

47/ The Right Words: The Patriot’s <strong>Churchill</strong> and <strong>Winston</strong> • Christopher H. Sterling<br />

48/ In the Dark Streets Shineth, by David McCullough • Michael Richards<br />

48/ Secrets of the Dead: <strong>Churchill</strong>’s Deadly Decision, a PBS Documentary • Earl Baker<br />

50/ My Years with the <strong>Churchill</strong>s, by Heather White-Smith • Barbara F. Langworth<br />

50/ The Man Who Saved Europe, by Klaus Wiegrefe • Max Edward Hertwig<br />

52/ <strong>Churchill</strong> in Fiction: Historical Characters in Need of Character • Michael <strong>Men</strong>amin<br />

54/ Education: How Guilty Were the German Field Marshals? • Rob Granger & the Editor<br />

62/ Moments in <strong>Time</strong>: <strong>Churchill</strong> in North Africa, August 1942 • Kevin Morris<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

2/ The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre • 4/ Despatch Box • 6/ Datelines • 6/ Quotation of the Season<br />

8/ Around & About • 10/ From the Editor • 31/ Riddles, Mysteries, Enigmas<br />

43/ Wit & Wisdom • 56/ Action This Day • 61/ <strong>Churchill</strong> Quiz<br />

FINESTHOUR150/3

D E S P A T C H B O X<br />

Number 150 • Spring 2011<br />

ISSN 0882-3715<br />

www.winstonchurchill.org<br />

____________________________<br />

Barbara F. Langworth, Publisher<br />

barbarajol@gmail.com<br />

Richard M. Langworth, Editor<br />

rlangworth@winstonchurchill.org<br />

Post Office Box 740<br />

Moultonborough, NH 03254 USA<br />

Tel. (603) 253-8900<br />

December-March Tel. (242) 335-0615<br />

__________________________<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Paul H. Courtenay, David Dilks,<br />

David Freeman, Sir Martin Gilbert,<br />

Edward Hutchinson, Warren Kimball,<br />

Richard Langworth, Jon Meacham,<br />

Michael Mc<strong>Men</strong>amin, James W. Muller,<br />

John Olsen, Allen Packwood, Terry<br />

Reardon, Suzanne Sigman,<br />

Manfred Weidhorn<br />

Senior Editors:<br />

Paul H. Courtenay<br />

James W. Muller<br />

News Editor:<br />

Michael Richards<br />

Contributors<br />

Alfred James, Australia<br />

Terry Reardon, Canada<br />

Antoine Capet, James Lancaster, France<br />

Paul Addison, Sir Martin Gilbert,<br />

Allen Packwood, United Kingdom<br />

David Freeman, Fred Glueckstein,<br />

Ted Hutchinson, Warren F. Kimball,<br />

Justin Lyons, Michael Mc<strong>Men</strong>amin,<br />

Robert Pilpel, Christopher Sterling,<br />

Manfred Weidhorn, United States<br />

___________________________<br />

• Address changes: Help us keep your copies coming!<br />

Please update your membership office when<br />

you move. All offices <strong>for</strong> The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre<br />

and Allied national organizations are listed on<br />

the inside front cover.<br />

__________________________________<br />

Finest Hour is made possible in part through the<br />

generous support of members of The <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Centre and Museum, the Number Ten Club,<br />

and an endowment created by the <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Centre Associates (page 2).<br />

___________________________________<br />

Published quarterly by The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre,<br />

offering subscriptions from the appropriate<br />

offices on page 2. Permission to mail at nonprofit<br />

rates in USA granted by the United<br />

States Postal Service, Concord, NH, permit<br />

no. 1524. Copyright 2011. All rights reserved.<br />

Produced by Dragonwyck Publishing Inc.<br />

SOMERVELL AWARD<br />

Issue 149 reminds me again to<br />

express gratitude <strong>for</strong> the kindness and<br />

support given my article, “Eye-Witness<br />

to Potsdam,” by the Finest Hour<br />

Editorial Board in naming it <strong>for</strong> the<br />

Somervell Award.<br />

Last week three local newspapers<br />

printed articles about the award, and I<br />

have been asked if I will give a story to<br />

the Liverpool Echo, which covers<br />

Merseyside. Local schools want me to<br />

appear as well so I am preparing to talk<br />

to future generations about what Sir<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> did <strong>for</strong> us all.<br />

NEVILLE BULLOCK, ASHTON, LANCS,<br />

STUDENTS’ CHOICE<br />

In discussing Richard Holmes’s In<br />

the Footsteps of <strong>Churchill</strong>, included in<br />

his “Five Best Recent <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Books,” (FH 148: 40), John P. Rossi<br />

quotes Holmes’s statement that<br />

“Without <strong>Churchill</strong>, Britain would<br />

have lost the war.” Mr. Holmes also<br />

stated (page 230, Basic Books paperback<br />

edition): “In 1940-41 Britain<br />

would not have survived as an independent<br />

nation had it not been <strong>for</strong> the<br />

agricultural, industrial and financial aid<br />

received from Canada.” By the end of<br />

World War II, Britain had received<br />

$3.5 billion in gifts from Canada, and<br />

more in loans.<br />

TERRY REARDON, ETOBICOKE, ONT.<br />

Editor’s response: In an interesting<br />

if depressing column, “Dependence<br />

Day,” in the January 2011 New<br />

Criterion, Mark Steyn writes: “Threesevenths<br />

of the G7 economies are<br />

nations of British descent. Two-fifths of<br />

the permanent members of the U.N.<br />

Security Council are—and, by the way,<br />

it should be three-fifths. The rap<br />

against the Security Council is that it’s<br />

the Second World War victory parade<br />

preserved in aspic, but if it were,<br />

Canada would have a greater claim to<br />

be there than either France or China”<br />

(http://xrl.us/biffwx).<br />

THANKS<br />

I must tell you that Finest Hour<br />

seems to be going from success to<br />

success and I find myself engrossed <strong>for</strong><br />

a day or two after each arrival. The<br />

current issue is perhaps the best ever.<br />

The in<strong>for</strong>mation about intelligence is<br />

new, at least to me, and fascinating.<br />

ROY M. PITKIN, LA QUINTA, CALIF.<br />

“GOOGLEWORLD”<br />

Your article on the digital world’s<br />

effects on joining organizations (FH<br />

148: 44) is intriguing. And worrying.<br />

How do any of us find financial<br />

support in Googleworld? I don't have<br />

an answer, but I think you are right.<br />

We cannot resist the tide, and must<br />

find ways of floating on it. Rupert<br />

Murdoch is making a brave attempt to<br />

move his newspapers to the web, but I<br />

think it is far from certain he will<br />

succeed. How long can we rely on the<br />

overly generous contributions of time<br />

and money from people who have sustained<br />

so many non-profits <strong>for</strong> so long?<br />

I don't know. You are entirely right to<br />

raise the issue and have it discussed.<br />

The worst aspect of the “<strong>Churchill</strong><br />

industry” is how parts of it refuse to<br />

move with the times, want everything<br />

to stay as it was—to see <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

through spectacles so deeply tinted<br />

with rose that they cannot look ahead.<br />

Incidentally, I spoke at the<br />

Imperial War Museum in December,<br />

supporting WSC as the Greatest British<br />

Prime Minister, during a debate <strong>for</strong><br />

London History Week. Talking about<br />

him to a diverse audience had them<br />

standing on their feet (and buying<br />

books). Whenever we manage to get<br />

the message across, I find it is always<br />

well received.<br />

LORD DOBBS, WYLYE, WILTS.<br />

SUTHERLAND PORTRAIT<br />

I take exception to the statement<br />

on page 5 (FH 148) that Clementine<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> was within her rights to<br />

destroy the 1954 portrait of Sir<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> by Graham Sutherland. This<br />

was a work of art commissioned by<br />

Parliament. As I see it, civilized people<br />

respect art even if they lack the ability<br />

to appreciate it. It would be more intelligent<br />

to publish photographs of the<br />

portrait, as well as Sutherland’s portraits<br />

of Somerset Maugham, Helena<br />

Rubinstein and Konrad Adenauer,<br />

together with a commentary from a<br />

qualified critic of modern portraiture.<br />

FINESTHOUR150/4

This would not include anyone in the<br />

employ of Hallmark greeting cards.<br />

National galleries and government<br />

offices are filled with portraits the<br />

subject disliked. Dolley Madison was<br />

willing to risk her life to save a Gilbert<br />

Stuart portrait of George Washington,<br />

whether or not Martha liked it. The<br />

National Trust spends time and money<br />

to preserve buildings, art and memorabilia,<br />

and would deplore the wanton<br />

destruction of so-called private property.<br />

It is <strong>for</strong>tuitous that Clementine<br />

did not destroy Chartwell, which she<br />

also disliked.<br />

ROBERT L. HALFYARD, N. QUINCY, MASS.<br />

Editor’s response: Lady <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

did not dislike Chartwell. Without her<br />

enthusiasm and support, preparing the<br />

house <strong>for</strong> exhibit by the National Trust<br />

would have been problematic. What<br />

she disliked, at least in the early years,<br />

was its expense.<br />

The controversy over the<br />

Sutherland painting is bewildering.<br />

Unlike Stuart’s Washington, it was not<br />

the property of the nation. It was<br />

private property, regardless of who presented<br />

it. Some believed that it should<br />

have been donated to the National<br />

Trust, even though it never hung at<br />

Chartwell. That has a familiar ring.<br />

Prominent people are <strong>for</strong>ever being<br />

told that they should give their property<br />

to society, that to do what they<br />

please with it is, well, tacky. The origin<br />

of this presumption lies in the belief<br />

that private property is literally a gift,<br />

which all right thinkers should pass<br />

along <strong>for</strong> appreciation by critics (in<br />

this case provided they don’t work <strong>for</strong><br />

Hallmark). A more sensitive view of<br />

the matter is in Lady Soames’s book on<br />

her father’s life as a painter, which we<br />

quoted.<br />

WINSTON: “A LONGING<br />

TO GO TO SEA”<br />

I am remiss in sharing a few cherished<br />

stories about time spent with Sir<br />

<strong>Winston</strong>’s late grandson, an experience<br />

which showed a surprising technical<br />

side of him that I didn’t read in the<br />

remembrances in Finest Hour 147.<br />

Soon after I had departed as commanding<br />

officer of USS <strong>Winston</strong> S.<br />

USS <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, DDG-81<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>, <strong>Winston</strong> wanted to visit the<br />

ship during one of his stays in<br />

Washington. I think he wanted to<br />

verify that the satellite TV he had purchased<br />

<strong>for</strong> the crew was working, that<br />

the ship had maintained its lavish publike<br />

chiefs’ mess, and that the books he<br />

so generously donated were not on<br />

display, but rather being read.<br />

We organized a rendezvous south<br />

of DC. The plan was <strong>for</strong> me to escort<br />

him to the Norfolk Navy Base in his<br />

chauffeured automobile. We had an<br />

intriguing talk during the three-hour<br />

drive. During intermissions, to let our<br />

jaws rest, he broke out his laptop and<br />

immediately began emailing, while<br />

speeding down I-95, his fingers flying<br />

across the keyboard.<br />

Since this preceded 4G networks<br />

and the common use of “hot zones,” I<br />

asked how he managed to get a signal.<br />

That unleashed a torrent of technospeak<br />

in reply. <strong>Winston</strong> went on and<br />

on about how to rig one’s car to maximize<br />

reception, the proper phone<br />

network in the central Atlantic states<br />

versus the Miami metropolitan area,<br />

burst transmissions, condensing emails,<br />

and other crucial tips to stay connected<br />

in the 21st century. The conversation<br />

continued into a truck stop (my recommendation—appropriate,<br />

I thought,<br />

since we had been discussing The Great<br />

Republic, his book on his grandfather’s<br />

writings of America). Alas we had an<br />

absolutely heinous meal, memorable to<br />

a fault. We laughed about that truck<br />

stop <strong>for</strong> the next two days.<br />

FINESTHOUR150/5<br />

The ship visit was pleasant <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>Winston</strong> and a bit emotional <strong>for</strong> me.<br />

He was most at home with the fire<br />

control and electronics technicians—<br />

the two ratings responsible <strong>for</strong> much of<br />

what makes a modern destroyer<br />

modern. [His grandfather is erroneously<br />

credited with coining the term<br />

“destroyer,” which actually dates to the<br />

1890s. —Ed.]<br />

Our drive home was about radar<br />

signals, wave theory, electro-magnetic<br />

induction, weapons control systems,<br />

and modern navigation techniques (he<br />

favored the old ways of navigation).<br />

For a journalist with a liberal arts education,<br />

he found a com<strong>for</strong>table niche in<br />

the techno-babble that is today’s Navy.<br />

I thought I saw in his eye a longing to<br />

go to sea.<br />

You may be interested to know<br />

that Sir <strong>Winston</strong>’s 1897 observations<br />

of the Northwest Frontier, also in<br />

Finest Hour 147, still hold true in the<br />

Punjabi region:<br />

…tribes war with tribes. Every man’s<br />

hand is against the other and all are<br />

against the stranger.…the state of continual<br />

tumult has produced a habit of<br />

mind which holds life cheap and<br />

embarks on war with careless levity and<br />

the tribesmen of the Afghan border<br />

af<strong>for</strong>d the spectacle of a people who<br />

fight without passion and kill one<br />

another without loss of temper….A<br />

trifle rouses their animosity. They<br />

make a sudden attack on some frontier<br />

post. They are repulsed. From their<br />

point of view the incident is closed.<br />

There has been a fair fight in which<br />

they have had the worst <strong>for</strong>tune. What<br />

puzzles them is that the “Sirkar”<br />

should regard so small an affair in a<br />

serious light.<br />

After two and a half years of<br />

dealing with the strategy, policy, and<br />

planning <strong>for</strong> the Middle East and the<br />

Central and South Asia regions, I find<br />

the young <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> as right<br />

today as he was in the days of the<br />

Malakand Field Force.<br />

Who knows…but my next posting<br />

may lead to a modern appreciation of<br />

The River War. Maybe even a unique<br />

destination <strong>for</strong> The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre’s<br />

meeting of the board. We shall see.<br />

RADM MICHAEL T. FRANKEN, USN<br />

UNITED STATES CENTRAL COMMAND ,

DAT E L I N E S<br />

1911-2011: THE SIDNEY STREET CENTENARY<br />

LONDON, DECEMBER 18TH—<br />

The Museum of London<br />

Docklands today opened a new<br />

exhibition, “London under Siege:<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> and the Anarchists,”<br />

featuring the Astrakhan-collared<br />

greatcoat <strong>Churchill</strong> wore when he<br />

controversially arrived at the scene<br />

to observe operations against<br />

criminals on 3 January 1911.<br />

(Reported by The Guardian website,<br />

http://xrl.us/bh68rg.)<br />

Mr. Clive<br />

Bettington of<br />

the Jewish<br />

East End<br />

Celebration<br />

Society, cosponsors<br />

of the<br />

exhibit, says<br />

Sidney Street “is part of East End and<br />

socialist folklore and the area at the<br />

time was home to radical political<br />

groups, most of whom had come from<br />

Eastern Europe, thus helping exaggerate<br />

people’s imaginations about<br />

immigration and other cultures.”<br />

If there’s any exaggeration it’s<br />

the publicity. A legal and warranted<br />

police action does not amount to<br />

“London under Siege.” Whether or<br />

not the “Latvian anarchists” cornered<br />

at Sidney Street were socialists, they<br />

were in the process of robbing a<br />

jewelry shop when the police were<br />

summoned. (See “Anarchism and<br />

Fire,” page 34.)<br />

The jeweler’s shop was at 119<br />

Houndsditch, near Cutler Street and<br />

Goring Street. The besieged house was<br />

at 100 Sidney Street, which runs north<br />

and south from Whitechapel Road to<br />

Commercial Road, near Whitechapel<br />

Underground station. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately<br />

there is little left to see of the neighborhood<br />

as it was in 1911, since it was<br />

rebuilt as the Sidney Street Estate in<br />

the postwar reconstruction of Stepney.<br />

One of the blocks at the end of the<br />

street was named “Siege<br />

House,” but number 100<br />

was actually on the east<br />

side, about halfway down,<br />

near Sidney Square.<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>’s presence<br />

at the scene in 1911<br />

pursued him a long time.<br />

Speaking in Shepherd’s<br />

Bush about the departing<br />

government be<strong>for</strong>e the<br />

general election of 3<br />

December 1923, WSC<br />

remarked: “In the brief period during<br />

which they held office they have not<br />

succeeded in handling a single public<br />

question with success.” The crowd<br />

laughed when a voice said, “They succeeded<br />

at the battle of Sidney Street,<br />

didn't they?” <strong>Churchill</strong> shot back: “We<br />

have always been wondering where<br />

Peter the Painter got to.”<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>’s account of the “Siege<br />

of Sidney Street” is in his Thoughts<br />

and Adventures, pages 63-72 of the<br />

new ISI Books edition edited by James<br />

W. Muller. <strong>Churchill</strong> concludes: “Of<br />

‘Peter the Painter’ not a trace was ever<br />

found. He vanished completely.<br />

Rumour has repeatedly claimed him as<br />

one of the Bolshevik liberators and<br />

saviours of Russia. Certainly his qualities<br />

and record would well have fitted<br />

him to take an honoured place in that<br />

noble band. But of this Rumour is<br />

alone the foundation.”*<br />

* One of FH’s contributors liked<br />

to tweak the editor, who is of part-<br />

Latvian extraction, by reiterating the<br />

claim (revived in current publicity)<br />

that the Sidney Street gang were<br />

“Latvian anarchists,” knowing that<br />

each time, the editor would faithfully<br />

edit this out! This was not to whitewash<br />

Latvians, but because the gang<br />

leader, “Peter the Painter” (variously<br />

identified as Peter Piatkow, Peter<br />

Straume or Jacob Peters) did not<br />

possess a Latvian name. Two accomplices<br />

who died in the blaze were Jacob<br />

FINESTHOUR150/6<br />

Quotation of the Season<br />

f a man is coming across the sea to<br />

“Ikill you, you do everything in your<br />

power to make sure he dies be<strong>for</strong>e finishing<br />

his journey. That may be difficult, it<br />

may be painful, but at least it is simple. We<br />

are now entering a world of imponderables,<br />

and at every stage occasions <strong>for</strong> self-questioning<br />

arise. Only one link in the chain of<br />

destiny can be handled at a time.”<br />

—WSC, HOUSE OF COMMONS,<br />

18 FEBRUARY 1945<br />

Vogel and Fritz Svaars; “Svaars” could<br />

be Latvian, but not “Fritz.”<br />

THE DREAM IN COLOMBO<br />

COLOMBO, NOVEMBER 20TH— Sri Lanka,<br />

the country <strong>Churchill</strong> knew as<br />

Ceylon, not unfamiliar with civil<br />

upheaval, reflected on his littleknown<br />

1947 short story, The Dream,<br />

(FH 125: 41, FH 126: 44). Part of<br />

the dialogue:<br />

Lord Randolph <strong>Churchill</strong>: “But<br />

tell me about these other wars.”<br />

<strong>Winston</strong>: “They were the wars<br />

of nations, caused by demagogues<br />

and tyrants.”<br />

LRC: “Did we win?”<br />

WSC: “Yes, we won all our<br />

wars. All our enemies were beaten<br />

down. We even made them surrender<br />

unconditionally.”<br />

LRC: “No one should be made<br />

to do that. Great people <strong>for</strong>get sufferings,<br />

but not humiliations.”<br />

WSC: “Well, that was the way<br />

it happened, Papa.”<br />

LRC: “How did we stand after<br />

it all? Are we still at the summit of<br />

the world, as we were under Queen<br />

Victoria?”<br />

WSC: “No, the world grew<br />

much bigger all around us.”<br />

LRC: “…<strong>Winston</strong>, you have<br />

told me a terrible tale. I would never<br />

have believed that such things could<br />

happen. I am glad I did not live to<br />

see them.” The article continues...

Finest Hour 56<br />

D A T E L I N E S<br />

In 1947, Sir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> wrote<br />

about a dream he had. He had been<br />

seated in his studio trying to paint a<br />

portrait of his father. He felt an odd<br />

sensation and turned around to see his<br />

father, then long dead, seated in the<br />

leather armchair behind him. A long<br />

conversation<br />

on a<br />

wide range<br />

of subjects<br />

followed,<br />

an extract<br />

of which is<br />

quoted<br />

opposite.<br />

This<br />

imaginary<br />

conversation<br />

between<br />

father and<br />

son seems appropriate now with the<br />

issue of the horrors of war coming up<br />

in evidence be<strong>for</strong>e the Sri Lanka<br />

Commission on Lessons Learnt and<br />

Reconciliation, and in some happenings<br />

connected to it.<br />

When Al-Jazeera published what<br />

it stated were still unverified photographs<br />

of the Eelam War [against Tamil<br />

separatists, won by the Sri Lanka government<br />

in 2009], the government<br />

spokesperson’s immediate reaction was<br />

to claim they were fakes. Recently, it<br />

has been repeated that there were zero<br />

civilian deaths due to offensives by the<br />

security <strong>for</strong>ces. On the contrary, there<br />

have been repeated claims by many<br />

civilians….<br />

These rival claims can only be<br />

verified by an independent inquiry,<br />

either by a specially constituted panel<br />

acceptable to most independent civil<br />

society organizations or by a Truth<br />

Commission on the lines of the Tutu<br />

Commission in South Africa. It is in<br />

the interests of the government to see<br />

that an independent inquiry is done.<br />

—FEDRICA JANZ, SRI LANKA GUARDIAN<br />

HEEERE’S ADOLF!<br />

BERLIN, OCTOBER 29TH— Germany has<br />

opened a Hitler Museum—but cynics<br />

who predicted an “Adolf Hitler Platz”<br />

one day will have to wait. The German<br />

Historical Museum’s exhibit, entitled<br />

“Hitler and the German Nation and<br />

Crime,” is devoted to the citizenry’s<br />

complicity in the Third Reich. This is<br />

new: <strong>for</strong> decades after the war, German<br />

students were taught that Hitler had<br />

effectively hijacked the nation as it<br />

stood and watched.<br />

“That much of the German<br />

people became enablers, colluders, cocriminals<br />

in the Holocaust” is now a<br />

mainstream view, says political analyst<br />

Constanze Stelenmüller. “But it took us<br />

a while to get there.” The exhibit consists<br />

largely of everyday objects that<br />

ordinary Germans made to glorify the<br />

Führer, such as a tapestry woven by<br />

church women interspersed with<br />

images of townsfolk, the Lord’s Prayer<br />

and the Swastika.<br />

“WSC DIDN’T SAY THAT”<br />

WASHINGTON, JANUARY 25TH— Ross<br />

Douthat describes The King’s Speech<br />

(reviewed on page 44) as “com<strong>for</strong>t food<br />

<strong>for</strong> Anglophiles [with] plummy accents,<br />

faultless sets, master thespians and an<br />

entirely unobjectionable political<br />

message (down with Hitler and snobbery,<br />

but God Save the King).” But<br />

Christopher Hitchens in Slate accuses<br />

the film of “gross falsifications of<br />

history” (www.slate.com/id/2282194/).<br />

Hitchens says it whitewashes <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

by painting him as an ally of George<br />

VI, who succeeded his brother, the<br />

“Nazi sympathizer” Edward VIII, when<br />

in fact the “bombastic” WSC stuck<br />

with Edward to the last, squandering<br />

his political capital as an anti-appeaser.<br />

Once Edward abdicated, the Royal<br />

Family, a “rather odd little German<br />

dynasty,” was “invested in the post-fabricated<br />

myth of its participation in<br />

‘Britain's finest hour.’”<br />

We were all set to send Slate a<br />

rebuttal, as over Hitchens’ Atlantic rant<br />

in 2002 (FH 114, http://xrl.us/bif47u),<br />

labeling <strong>Churchill</strong> “incompetent,<br />

boorish, drunk and mostly wrong.” But<br />

Slate readers responding on their<br />

website spared us the task.<br />

The film emphasizes <strong>Churchill</strong>’s<br />

instinctive support <strong>for</strong> the monarchy,<br />

which is accurate. Edward VIII was a<br />

regrettable character, not even controllable<br />

as governor of the Bahamas,<br />

where several kettles of ripe fish were<br />

left when he quit<br />

Nassau. But his pro-<br />

Nazi ideas (which<br />

Hitchens incorrectly<br />

says “never ceased”)<br />

were as shallow as the<br />

rest of him, probably<br />

stemming from his<br />

admiration of how<br />

Herr Hitler got his way without the<br />

inconvenience of a Parliament.<br />

King George VI was scarcely<br />

alone in supporting Chamberlain and<br />

appeasement. A whole generation had<br />

been wasted in World War I, as Alistair<br />

Cooke elegantly put it during the 1988<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> Conference: “The British<br />

people would do anything to stop<br />

Hitler, except fight him. And if you<br />

had been there, ladies and gentlemen—<br />

if you had been alive and sentient and<br />

British in the mid-Thirties—not one in<br />

ten of you would have supported Mr.<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>.”<br />

King George<br />

VI’s deportment in<br />

World War II won<br />

him the lasting<br />

respect of his people,<br />

eclipsing his mistaken<br />

beliefs be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

1940. <strong>Churchill</strong>’s<br />

political reverse after<br />

Edward VIII<br />

George VI<br />

defending Edward VIII was brief and<br />

insignificant; his comeback as “Prophet<br />

of Truth” was soon back on track as<br />

events proved he’d been right all along.<br />

Gross falsifications of history? All<br />

we have here is the grossly iconoclastic<br />

Chris Hitchens, personification of the<br />

Member of Parliament described by<br />

Arthur Balfour: “The hon. gentleman<br />

has said much that is trite and much<br />

that is true, but what’s true is trite, and<br />

what’s not trite is not true.”<br />

—EDITOR<br />

“WSC WROTE ABOUT IT”<br />

NEW YORK, NOVEMBER 16TH— Columnist<br />

Bret Stephens on “America’s Will to<br />

Weakness”: “Beijing provokes clashes<br />

with the navies of Indonesia and Japan<br />

as part of a bid to claim the South<br />

China Sea. Tokyo is in a serious diplomatic<br />

row with Russia over the South<br />

Kuril islands, a leftover dispute from<br />

1945. There are credible fears that >><br />

FINESTHOUR150/7

D A T E L I N E S<br />

Teheran and Damascus will overthrow<br />

the elected Lebanese government.<br />

Managua is attempting to annex a<br />

sliver of Costa Rica, a nation much too<br />

virtuous to have an army of its own.<br />

And speaking of Nicaragua, Daniel<br />

Ortega is setting himself up as another<br />

Hugo Chávez by running, unconstitutionally,<br />

<strong>for</strong> another term. Both men<br />

are friends and allies of Mahmoud<br />

Ahmadinejad,.”<br />

All this was written be<strong>for</strong>e Egypt<br />

and Libya exploded, Pakistan abducted<br />

a U.S. diplomat, and Argentina, which<br />

the U.S. obliges by calling the Falkland<br />

Islands “Malvinas,” confiscated a U.S.<br />

plane used in a joint training exercise.<br />

Stephens continues: “We are now<br />

at risk of entering a period—perhaps a<br />

decade, perhaps a half-century—of<br />

global disorder, brought about by a<br />

combination of weaker U.S. might and<br />

even weaker U.S. will. The last time we<br />

saw something like it was exactly a<br />

century ago. <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> wrote<br />

a book about it: The World Crisis.<br />

Worth reading today.” Stephens’<br />

column is at: http://xrl.us/bh7377.<br />

DR. WHO?<br />

FULLERTON, CALIF, DECEMBER 15TH— The<br />

following was submitted to me as an<br />

essay on a final exam taken this week.<br />

(If you don’t know who “The Doctor”<br />

is, skip this note or Google Dr. Who.)<br />

“<strong>Churchill</strong> is known <strong>for</strong> as the<br />

British Prime Minister during World<br />

War II. He saw the threat that Hitler<br />

presented, unlike Neville Chamberlain,<br />

who thought, ‘Hitler seems like a right<br />

fine old chap.’ <strong>Churchill</strong> also coined<br />

the ‘iron curtain’ phrase regarding<br />

Communism. What most people don't<br />

know about <strong>Churchill</strong> is that he was a<br />

personal friend of The Doctor, or at<br />

least he knew The Doctor well enough<br />

to know his phone number and be able<br />

to call him in the TARDIS.<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> summoned The<br />

Doctor during World War II when the<br />

Daleks had infiltrated the underground<br />

war cabinet, masquerading as weapon<br />

designed to defeat Hitler, by a British<br />

scientist who turned out to be an<br />

android created by the Daleks and<br />

given fake human memories.<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>, it appears later helped River<br />

AROUND & ABOUT<br />

Manfred Weidhorn sends us an excerpt from the<br />

Diaries of Josef Goebbels, Nazi propaganda chief,<br />

dated 8 May 1941, a year after <strong>Churchill</strong> had come to<br />

power. Hitler and Goebbels regularly lambasted <strong>Churchill</strong> as<br />

an aging, delusional liar, Prof. Weidhorn writes; but in his personal daily<br />

diary, Goebbels reflected on what he really thought:<br />

“I study <strong>Churchill</strong>'s new book Step by Step, Speeches from 1936-39<br />

and essays. This man is a strange mixture of heroism and cunning. If he had<br />

come to power in 1933, we would not be where we are today. And I believe<br />

that he will give us a few more problems yet. But we can and will solve them.<br />

Nevertheless he is not to be taken lightly as we usually take him.”<br />

For more public and private Goebbels opinions, see Randall Bytwerk,<br />

“<strong>Churchill</strong> in Nazi Cartoon Propaganda,” Finest Hour 143, Summer 2009.<br />

kkkkk<br />

On a pundit panel last November 7th, Mara Liasson of National<br />

Public Radio likened outgoing Speaker of the House of Representatives<br />

Nancy Pelosi, then battling to remain her party’s leader in the House after<br />

her party sustained major losses in the November elections, to <strong>Winston</strong><br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>. This was rebutted by Fox News senior political analyst Brit Hume,<br />

who said that unlike Pelosi, <strong>Churchill</strong> had stayed on after winning a great<br />

victory—World War II. (For the video see http:// xrl.us/bh69x8.)<br />

Liasson and Hume are both right and both wrong. <strong>Churchill</strong> was dismissed<br />

in 1945, despite the approaching complete victory in World War II,<br />

while Pelosi lost the Speakership after a great electoral loss (per Hume).<br />

But <strong>Churchill</strong>, like Pelosi, declared that he would remain party leader despite<br />

electoral defeat (per Liasson).<br />

The issue is obfuscated because the offices aren’t comparable. In<br />

America, The Speaker of the House of Representatives, third in line <strong>for</strong> the<br />

presidency and party leader in the House, is far more important than the<br />

Speaker of the House of Commons, who is a party politician but “independent<br />

of party” when Speaker. And in America the President is always the<br />

titular leader of his party. Still, a Pelosi comeback in 2012, like <strong>Churchill</strong>’s in<br />

1951, would be bound to produce more comparisons. Over and above the<br />

contemporary politics, it’s nice to know that <strong>Churchill</strong> is still the benchmark<br />

by which today’s players are measured. ,<br />

Song get the painting Vincent Van<br />

Gogh made of the TARDIS exploding<br />

to the Doctor to warn him of the<br />

Pandora Opening.”<br />

—DAVID FREEMAN<br />

Editor’s note: Doctor Who<br />

episodes frequently involve historical<br />

figures, though we’re not quite sure<br />

how tongue-in-cheek this submission<br />

was. TARDIS, Doctor Who’s time traveling<br />

device, is short <strong>for</strong> “<strong>Time</strong> and<br />

Relative Distance in Space,” and the<br />

Daleks are the evil robots bent on<br />

world domination. But it will take a<br />

better Dr. Who fan than we to identify<br />

River Song and the Pandora Opening!<br />

Readers please help....<br />

“KARSH 4” UNEARTHED<br />

VANCOUVER, FEBRUARY 2010— In a master’s<br />

thesis entitled “By the Side of the<br />

‘Roaring Lion,’” University of Calgary<br />

graduate student Rebecca Lesser uncovered<br />

a fourth in the series of <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

photographs snapped by Yousuf Karsh<br />

after <strong>Churchill</strong>’s “Some Chicken—<br />

Some Neck” speech to the Canadian<br />

Parliament in Ottawa on 30 December<br />

1941. Referred by Terry Reardon, she<br />

sent us her manuscript, which is available<br />

from the editor by email. Ms.<br />

Lesser notes that Karsh snapped several<br />

candid photographs of the two leaders:<br />

“It was Mackenzie King who had<br />

arranged <strong>for</strong> Karsh’s photographic<br />

encounter with <strong>Churchill</strong>…“he was as<br />

FINESTHOUR150/8

eager to be photographed with his<br />

British counterpart as Karsh himself<br />

was to photograph <strong>Churchill</strong>.<br />

The third photo, “Karsh 3,” not<br />

pictured by Lesser, was in Karsh’s<br />

account in FH 94; and Terry Reardon’s<br />

“<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> and Mackenzie<br />

King” in FH 130.<br />

Rebecca Lesser’s fourth photo,<br />

first published on 10 January 1942 in<br />

Canada’s weekly general-interest magazine<br />

Saturday Night, “depicts a<br />

laughing Mackenzie King glancing over<br />

at <strong>Churchill</strong>, who in turn looks into<br />

the camera with a slight smile. The<br />

photograph was deemed unsuitable by<br />

King, as he felt that their jovial expressions<br />

were inappropriate <strong>for</strong> the serious<br />

nature of their meeting; he had not<br />

been posing <strong>for</strong> this photograph, and<br />

thus had not been granted the opportunity<br />

to constitute himself into the<br />

image he wished to convey. King’s<br />

concern regarding the public reception<br />

of such unposed images assured that<br />

these other photographs from that<br />

most famous sitting would be relegated<br />

to the archives.”<br />

We have always thought that<br />

Karsh’s “afterthought” photos of King<br />

and <strong>Churchill</strong> together (which, unlike<br />

the more famous pair, were never<br />

retouched) convey a truer picture of<br />

both statesmen. We continue to<br />

wonder exactly how many photos<br />

Karsh actually shot that day in Ottawa.<br />

TRUE AND TRITE<br />

NEW YORK, OCTOBER 1ST— Richard Toye’s<br />

biased and lopsided <strong>Churchill</strong>’s Empire<br />

WHICH KARSH IS THE TRUEST CHURCHILL?<br />

Below left: “Karsh 1,” the “Roaring Lion,” taken after Karsh plucked the cigar from <strong>Churchill</strong>’s<br />

mouth, resulting in a world-famous grimace. Below right: “Karsh 2,” the “Smiling Lion,” taken<br />

after WSC laughed and said, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed.”<br />

Bottom left: “Karsh 3,” with Mackenzie King—which we think is yet more<br />

genuine. Bottom right: “Karsh 4,” Rebecca Lesser’s discovery, perhaps the best of the lot.<br />

(let off lightly in FH 147) continues to<br />

cast a trail of misin<strong>for</strong>mation. In The<br />

New Yorker of August 30th, Adam<br />

Gopnik wrote a balanced account<br />

(http://xrl.us/bidbyp) of the continuing<br />

interest in and new books about<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>, which drew the following<br />

response from a reader in New Mexico:<br />

“Adam Gopnik’s article on<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> glides over the<br />

damning portrait of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s turn-ofthe-century<br />

exploits in Richard Toye’s<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>’s Empire: The World That<br />

Made Him and the World He Made. It<br />

is hard to reconcile the <strong>Churchill</strong> who<br />

believed that ‘imperialism and progressivism<br />

were parts of the same package,’<br />

and who lamented the death camps of<br />

the Holocaust, with the <strong>Churchill</strong> who<br />

dispatched hundreds of thousands of<br />

Kenyan Kikuyu, including President<br />

Obama’s grandfather, to torturous detention<br />

camps (‘Britain’s Gulag,’ in the<br />

words of the historian Caroline Elkins);<br />

who spoke of Indians as ‘a beastly people<br />

with a beastly religion,’ and who said that<br />

‘the Aryan stock is bound to triumph.’<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>’s imperial vision reminds us<br />

that a reconsideration of his political<br />

principles must not be confined to the<br />

era that shaped his finest hour.”<br />

To The New Yorker:<br />

The allegation that the<br />

President’s grandfather was a Mau Mau<br />

rebel tortured by the British stems<br />

from a blogsite and/or Obama’s<br />

“Granny Sarah,” who also claimed that<br />

the President was born in Kenya. The<br />

Mau Mau rebellion didn’t begin until<br />

the end of 1952 (a year after Obama’s<br />

grandfather was proven innocent and<br />

released), and <strong>Churchill</strong> actually<br />

expressed sympathy <strong>for</strong> the Kenyan<br />

rebels (http://xrl.us/bhwooo). The parliamentary<br />

<strong>for</strong>ms extant in India and<br />

developing in Kenya stem from the<br />

British rule your reader deplores. The<br />

“Aryan stock” quotation does not<br />

appear in <strong>Churchill</strong>’s canon. For better<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation than that provided by<br />

author Toye, he might want to rely on<br />

more balanced accounts, such as<br />

Arthur Herman (Gandhi and<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>), who knows what <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

really thought and did about India<br />

(http://xrl.us/bic86y). —RML ,<br />

FINESTHOUR150/9

T H E M E O F T H E I S S U E<br />

Tigers and Lions: Age and Leadership<br />

“Great captains must take their chance with the rest.<br />

Caesar was assassinated by his dearest friend. Hannibal<br />

was cut off by poison. Frederick the Great lingered out<br />

years of loneliness in body and soul. Napoleon rotted at<br />

St. Helena. Compared with these, Marlborough<br />

had a good and fair end to his life.”<br />

—WSC, Marlborough, vol. IV, 1938<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> served his last term as<br />

Prime Minister between 1951 and 1955,<br />

leaving at the age of 80. Georges<br />

Clemenceau served his last term as Prime Minister of<br />

France from 1917 to 1920, leaving at the age of 79. Each<br />

entered politics under the age of 30, supporting himself<br />

through writing. Each was a radical in his youth, growing<br />

more conservative as he aged. Far beyond retirement age,<br />

each inspired his countrymen, who knew them respectively<br />

as France’s Tiger and Britain’s Lion.<br />

Overt similarities aside, as Paul Alkon suggests<br />

herein, there is powerful evidence that <strong>Churchill</strong> patterned<br />

his own political attitudes after Clemenceau,<br />

whom he deeply admired—and that Clemenceau,<br />

although <strong>Churchill</strong> was the much younger man,<br />

unproven when they met, also admired him.<br />

Clemenceau died in 1929, too soon to consider any<br />

parallels of his career with <strong>Churchill</strong>’s. Indeed, a comparison<br />

between them would never have arisen, were it not<br />

<strong>for</strong> 1940 and <strong>Churchill</strong>’s finest hour. In that signal year,<br />

aged over 65, WSC was brought to office by other old<br />

men—not the “troublesome young men” of one recent<br />

book but troubled older men from three different parties.<br />

Their unity of faith and action made <strong>Churchill</strong> their<br />

nation’s leader at precisely the right time.<br />

Don Graeter’s “A <strong>Time</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Old</strong> <strong>Men</strong>” focuses on<br />

those days in 1940, and the aging individuals who made<br />

the difference in Britain’s hour of peril. As such, his piece<br />

is well qualified to lead our features on this theme.<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> was thought to be politically finished in<br />

1945, when the country flung him from office on the eve<br />

of complete victory over all Britain’s enemies. But he<br />

thought otherwise. When the editor of The <strong>Time</strong>s had<br />

the effrontery to suggest that <strong>Churchill</strong> should carry<br />

himself as a national leader and not remain long on the<br />

scene, his replies were characteristic, and illuminating:<br />

“Mr. Editor, I fight <strong>for</strong> my corner….I leave when the<br />

pub closes.” And he meant it—as we learn from Terry<br />

Reardon’s “Reluctant Retiree,” and Barbara Leaming’s<br />

outstanding new book, <strong>Churchill</strong> Defiant.<br />

How did <strong>Churchill</strong> do it? John Mather provides the<br />

physical explanation: how a fast-aging statesman, packing<br />

the baggage, the ups and downs of a record career in politics,<br />

somehow defied most medical advice and all<br />

actuarial probabilities from 1940 to his final retirement<br />

four months short of his 90th birthday.<br />

“Great captains must take their chance with the<br />

rest.” <strong>Churchill</strong> took his chance, and like John <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

First Duke Marlborough, he “had a good and fair end to<br />

his life.” It wasn’t all he had hoped <strong>for</strong>: his goal of permanent<br />

world peace remained elusive—as it remains<br />

today. Yet who can gainsay his record?<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> thought at the end of his life that he had<br />

“worked very hard and achieved a great deal, only to<br />

achieve nothing in the end.” With our longer perspective,<br />

we may disagree. <strong>Churchill</strong> did not win World War<br />

II: what he did was not lose it. “Only <strong>Churchill</strong>,”<br />

Charles Krauthammer wrote, “carries that absolutely<br />

required criterion: indispensability. Without <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

the world today would be unrecognizable—dark, impoverished,<br />

tortured.” And Charles de Gaulle remarked: “In<br />

the great drama, he was the greatest.”<br />

What can the world’s Democracies learn from<br />

the long careers, devotion to liberty, and<br />

lifetime defiance of odds by leaders like<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> and Clemenceau, who lived their finest hours<br />

well over retirement age? Is something to be said <strong>for</strong><br />

electing leaders with thirty or <strong>for</strong>ty years’ political experience?<br />

Or is this to be avoided, absent a very special type<br />

of character, like Britain’s Lion or France’s Tiger?<br />

That is the theme and purpose of this issue of<br />

Finest Hour. We take no position at the end. Perhaps<br />

none can be taken, because history never repeats, as<br />

Mark Twain quipped—”though it sometimes rhymes.”<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> alone could not save the world. But<br />

we can’t resist wondering if others like him will be there<br />

when we need them—and if we will have the <strong>for</strong>titude,<br />

like the <strong>Old</strong> <strong>Men</strong> of 1940, to hand them the job. We’ll<br />

see—and probably soon.<br />

RICHARD M. LANGWORTH, EDITOR ,<br />

FINESTHOUR150/10

A G E A N D L E A D E R S H I P<br />

May 1940: A <strong>Time</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Old</strong> <strong>Men</strong><br />

This improbable political thriller actually happened. An unlikely group of elderly gentlemen<br />

delivered three dramatic, perfectly timed speeches that set in motion a stream of events<br />

which changed the course of history. It was, truly, a time <strong>for</strong> old men.<br />

D O N<br />

C. G R A E T E R<br />

HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY<br />

“I HAVE FRIENDS”: Extremely rare (because photographs were not then allowed in the Commons) this historic photo was surreptitiously snapped with<br />

a Minox spy camera by Conservative MP John Moore-Brabazon. It shows the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, declaiming on the first day of the<br />

Norway debate, 7 May 1940, with John Simon and <strong>Churchill</strong> on the front bench above the gangway. Three days later, <strong>Churchill</strong> was Prime Minister.<br />

House of Commons, London<br />

Tuesday, 7 May 1940<br />

3:00 pm<br />

The Alcoholic Barrister had risen from modest Welsh<br />

roots. A successful King’s Counsellor, he was as well a<br />

respected Member of Parliament, though isolated as an<br />

independent. Few were aware of his carefully concealed penchant<br />

<strong>for</strong> binge drinking. Largely <strong>for</strong>gotten today, he will<br />

play a critical role in our drama.<br />

3:15 pm<br />

At 71, the Prime Minister was a very old man at a<br />

time when life expectancy was 59. He had been patient,<br />

however—had waited his turn to lead the country. He did<br />

things his own way. After all, he knew best.<br />

The Prime Minister hardly bothered to conceal his<br />

contempt <strong>for</strong> His Majesty’s Opposition: the Labour Party<br />

and a handful of disaffected Liberals. What did they matter<br />

with his huge Conservative majority? He tolerated no disloyalty<br />

in his own Tory ranks, where his opponents were<br />

few and of little consequence; and those he would crush. >><br />

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Mr. Graeter is Director of Investments <strong>for</strong> Central Bank of Louisville, Kentucky. He is a graduate of the University of Virginia Law School<br />

and served as a U.S. Navy officer during the Vietnam War. This article is adapted from his remarks to The Forum Club of Louisville.<br />

FINESTHOUR150/11

A TIME FOR OLD MEN...<br />

He knew who they were—had had them under surveillance<br />

<strong>for</strong> some time. Impatiently, the PM glanced at his watch,<br />

anxious to adjourn <strong>for</strong> the Whitsun holiday.<br />

3:30 pm<br />

Heads turned as the Admiral walked down Whitehall.<br />

Rarely did Londoners encounter a naval officer on the street<br />

in the full dress uni<strong>for</strong>m of an Admiral of the Fleet.<br />

Much decorated <strong>for</strong> bravery, the Admiral, now 67,<br />

had retired a hero. Financially secure from the success of his<br />

memoirs, he had entered Parliament <strong>for</strong> North Portsmouth<br />

in 1934. The Conservative Party had been delighted, since<br />

no one could beat a naval icon in Portsmouth.<br />

After a career of danger and hardship, the Admiral had<br />

anchored in tranquil waters, splitting his time between his<br />

country estate and “the best club in London,” as the House<br />

of Commons was known. Politically unambitious, he had<br />

supported his party; yet he now found himself among a<br />

small group of Tory backbenchers increasingly discontented<br />

with the Prime Minister’s leadership.<br />

The business be<strong>for</strong>e the House was procedural—a<br />

motion to adjourn <strong>for</strong> the holiday. But custom dictated that<br />

Members could speak on any topic. The Admiral had<br />

decided to seize the opportunity. He had had enough. No<br />

orator, he would condemn the Prime Minister’s leadership.<br />

He knew the risk of being run out of the party and<br />

deprived of his seat. Well, let the younger, ambitious ones<br />

worry about such things. He would do what he thought was<br />

right and, if necessary, leave public life <strong>for</strong>ever.<br />

7:09 pm<br />

The Admiral rose to deliver his only major speech. His<br />

voice was weak and he visibly trembled. The benches fell<br />

silent, out of respect <strong>for</strong> who he was and because of his<br />

dress uni<strong>for</strong>m, worn <strong>for</strong> just this purpose. Six rows of<br />

medals adorned his chest, glittering gold bands ran from his<br />

cuffs to his elbows. His voice did not match the splendor of<br />

his appearance, but the Admiral commanded rapt attention.<br />

The chamber hung on his every word.<br />

He began by criticizing the current British war campaign<br />

as “a shocking story of ineptitude.” He praised the<br />

First Lord of the Admiralty, who, he said, had “the confidence<br />

of the Navy, and indeed of the whole country.” But<br />

“proper use” of the First Lord’s “great abilities” could not<br />

be made “under the existing system.”<br />

8:03 pm<br />

Internal turmoil gripped the Scholar, another discontented<br />

Tory backbencher. He too was 67. Fluent in nine<br />

languages, he had taken a first at Balliol, and had been<br />

elected a fellow of All Souls at an early age. A prominent<br />

journalist, he had won acclaim as a military and political<br />

historian.<br />

In the 1920s, when the Scholar had served as First<br />

Lord of the Admiralty and Secretary of State <strong>for</strong> the<br />

Colonies, <strong>Time</strong> had called him the most talented member<br />

of the cabinet, though criticizing his pugnacious manner.<br />

But his party had been ousted in 1929, and in the national<br />

government that followed he had not been invited back.<br />

His career seemed well behind him.<br />

Aware of his reputation as an indifferent speaker, the<br />

Scholar had toiled mightily on the remarks he hoped to<br />

make. Still he was unsure—both of himself and of how far<br />

he should go. He shared the Admiral’s views, but he owed<br />

his seat to the Prime Minister, and the PM had been his<br />

friend. Given his seniority, the Scholar should have been<br />

recognized early—but the Speaker was a political foe and<br />

ignored him until the chamber of the House had nearly<br />

emptied <strong>for</strong> dinner.<br />

“I came to the House of Commons today in uni<strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong> the first<br />

time because I wish to speak <strong>for</strong> some officers and men of the<br />

fighting, sea-going Navy....The enemy have been left in undisputable<br />

possession of vulnerable ports and aerodromes <strong>for</strong> nearly a<br />

month, have been given time to pour in rein<strong>for</strong>cements by sea and<br />

air, to land tanks, heavy artillery and mechanised transport, and<br />

have been given time to develop the air offensive....It is not the fault<br />

of those <strong>for</strong> whom I speak....If they had been more courageously and<br />

offensively employed they might have done much to prevent these<br />

unhappy happenings and much to influence unfriendly neutrals.” —The Admiral<br />

FINESTHOUR150/12

“We are fighting today <strong>for</strong> our life, <strong>for</strong> our liberty, <strong>for</strong> our all;<br />

we cannot go on being led as we are. I have quoted certain<br />

words of Oliver Cromwell. I will quote certain other words. I<br />

do it with great reluctance, because I am speaking of those who<br />

are old friends and associates of mine, but they are words<br />

which, I think, are applicable to the present situation. This is<br />

what Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it<br />

was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation: ‘You have<br />

sat too long here <strong>for</strong> any good you have been doing. Depart, I<br />

say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!’" —The Scholar<br />

He had almost decided to <strong>for</strong>go<br />

comment when from behind came the<br />

urgent tones of the Alcoholic Barrister:<br />

“Now is the time. You must speak.<br />

Play <strong>for</strong> time. I’ll get you a crowd.”<br />

Gripped by doubt, the Scholar<br />

rose and began to address a nearly<br />

empty House. But the Alcoholic<br />

Barrister had repaired to the lobbies<br />

The Alcoholic Barrister<br />

and smoking room and, good as his<br />

word, soon produced a crowded Chamber.<br />

Encouraged by the increasing crowd, the Scholar<br />

described the government’s “handling of economic warfare,”<br />

indeed “the whole of our national ef<strong>for</strong>t,” as “too little, too<br />

late….We cannot go on as we are. There must be a change.”<br />

The chamber roared its approval. Emboldened, the<br />

Scholar made a fateful decision—to include a quotation he<br />

had accidentally discovered, never thinking the opportunity<br />

would arise to use it:<br />

“This is what Cromwell said to the Long Parliament<br />

when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs<br />

of the nation: ‘You have sat too long here <strong>for</strong> any good you<br />

have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with<br />

you. In the name of God, go!’”<br />

Wednesday, 8 May 1940<br />

4:00 pm<br />

The speeches resumed the next day, as the Elder<br />

Statesman brooded in his office. Once a noted orator, he<br />

was now 77, his days of leadership long past. He had not<br />

given a major speech in five years. Disgusted with both<br />

events and the Prime Minister, whom he held in open contempt,<br />

he planned to take no part in the debate. Though<br />

several colleagues begged him to intervene, he no longer<br />

had a significant following. What was the point?<br />

In the Chamber the Opposition—which had noted<br />

the violent split in Conservative ranks after last night’s<br />

speeches by the Admiral and the Scholar—opened by<br />

calling <strong>for</strong> a division: a vote of confidence in the government.<br />

Stung by their effrontery, the Prime Minister angrily<br />

interrupted: “I have friends in the House…and I call on my<br />

friends to support us in the Lobby tonight.”<br />

At this the Elder Statesman’s daughter, herself an MP,<br />

left the House to see her father. Breathlessly she told him<br />

what the Prime Minister had just said. The Elder<br />

Statesman, furious, said he could not remain silent.<br />

As he headed to the Chamber, the Elder Statesman<br />

gathered his thoughts—eighteen years since the Coalition<br />

he led had been thrown out in a rebellion of its Tory<br />

members. Revenge, indeed, was a dish best served cold.<br />

5:37 pm<br />

With a slight motion to the Speaker, the Elder<br />

Statesman was promptly recognized. Even at his age, the<br />

Speaker dared not keep him waiting.<br />

He began with a quip which drew laughter, and took<br />

his time as the Speaker called <strong>for</strong> order and the word spread<br />

to MPs outside the Commons that he was “up.” Members<br />

rushed back into the Chamber, which was soon full. The<br />

Elder Statesman began making his case. He would never<br />

give another memorable speech in the House. Did he have<br />

one last great oration in him?<br />

He told the House he had been reluctant to speak, but<br />

felt obliged to do so because of his experience as Prime<br />

Minister during the previous war; and this was no time to<br />

mince words. The Government's ef<strong>for</strong>ts, he continued, had<br />

been done “half-heartedly, ineffectively, without drive and<br />

unintelligently. Will anybody tell me that he is satisfied with<br />

what we have done about aeroplanes, tanks, guns?…Is<br />

anyone here satisfied with the steps we took to train an<br />

Army to use them? Nobody is satisfied.” >><br />

FINESTHOUR150/13

A TIME FOR OLD MEN...<br />

To the surprise of some who knew their mixed history<br />

as <strong>for</strong>mer colleagues, the Elder Statesman tried to exculpate<br />

one member of the government: “I do not think the First<br />

Lord was responsible <strong>for</strong> all the things that happened.” The<br />

First Lord of the Admiralty immediately interrupted: “I take<br />

full responsibility <strong>for</strong> everything that has been done by the<br />

Admiralty, and I take my full share of the burden.” The<br />

Elder Statesman replied that the First Lord must not allow<br />

himself “to be converted into an air-raid shelter to keep the<br />

splinters from hitting his colleagues.”<br />

Then, like the Scholar, the Elder Statesman reached<br />

his carefully-timed peroration. Turning to the Prime<br />

Minister, he spoke directly and devastatingly: “He has<br />

appealed <strong>for</strong> sacrifice. The nation is prepared <strong>for</strong> every sacrifice<br />

so long as it has leadership. I say solemnly that the<br />

Prime Minister should give an example of sacrifice, because<br />

there is nothing which can contribute more to victory in<br />

this war than that he should sacrifice the seals of office.”<br />

Monday, 13 May 1940<br />

4:00 pm<br />

As the Commons reconvened, the Pariah rose to<br />

address a now bewildered assembly. Aged 65, he had arrived<br />

here <strong>for</strong>ty years be<strong>for</strong>e. After a remarkable career of ups and<br />

downs, including twice changing parties, his career had<br />

foundered. He had spent the last decade on the back<br />

benches, lonely and frustrated. Even though he had rejoined<br />

the government as First Lord of the Admiralty the previous<br />

autumn, Conservatives who shared his views still avoided<br />

him, afraid of being tainted by association.<br />

The Pariah’s detractors were not limited to Tories. The<br />

Labour Party detested him <strong>for</strong> sins, and imagined sins,<br />

stretching back decades. A reporter had labeled him “a man<br />

without a party.” While his brilliance and industry were<br />

respected, he was also thought to be out of touch and<br />

lacking in judgment. “Rogue elephant,” “aging adventurer”<br />

and—the worst cut of all—“half-breed American” were<br />

among their derogatory descriptions. Just a year be<strong>for</strong>e, he<br />

had barely survived “deselection” as the Tory candidate <strong>for</strong><br />