WEBSITE APPENDIX A Personality, Abilities and Motivations

WEBSITE APPENDIX A Personality, Abilities and Motivations

WEBSITE APPENDIX A Personality, Abilities and Motivations

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>WEBSITE</strong> <strong>APPENDIX</strong> A<br />

<strong>Personality</strong>, <strong>Abilities</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Motivations</strong><br />

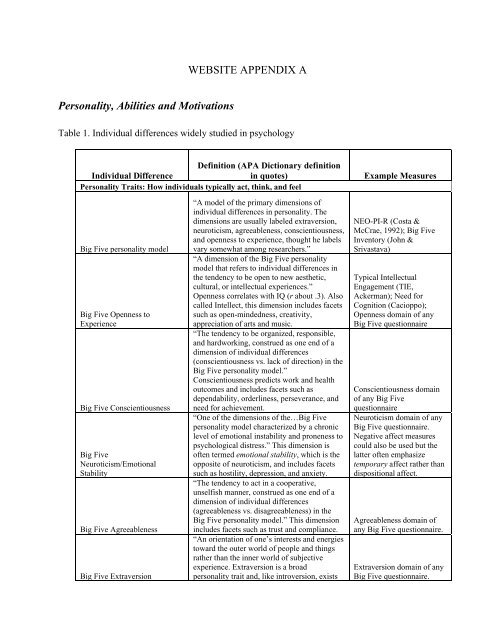

Table 1. Individual differences widely studied in psychology<br />

Definition (APA Dictionary definition<br />

Individual Difference<br />

in quotes)<br />

<strong>Personality</strong> Traits: How individuals typically act, think, <strong>and</strong> feel<br />

Example Measures<br />

Big Five personality model<br />

Big Five Openness to<br />

Experience<br />

Big Five Conscientiousness<br />

Big Five<br />

Neuroticism/Emotional<br />

Stability<br />

Big Five Agreeableness<br />

Big Five Extraversion<br />

“A model of the primary dimensions of<br />

individual differences in personality. The<br />

dimensions are usually labeled extraversion,<br />

neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness,<br />

<strong>and</strong> openness to experience, thought he labels<br />

vary somewhat among researchers.”<br />

“A dimension of the Big Five personality<br />

model that refers to individual differences in<br />

the tendency to be open to new aesthetic,<br />

cultural, or intellectual experiences.”<br />

Openness correlates with IQ (r about .3). Also<br />

called Intellect, this dimension includes facets<br />

such as open-mindedness, creativity,<br />

appreciation of arts <strong>and</strong> music.<br />

“The tendency to be organized, responsible,<br />

<strong>and</strong> hardworking, construed as one end of a<br />

dimension of individual differences<br />

(conscientiousness vs. lack of direction) in the<br />

Big Five personality model.”<br />

Conscientiousness predicts work <strong>and</strong> health<br />

outcomes <strong>and</strong> includes facets such as<br />

dependability, orderliness, perseverance, <strong>and</strong><br />

need for achievement.<br />

“One of the dimensions of the…Big Five<br />

personality model characterized by a chronic<br />

level of emotional instability <strong>and</strong> proneness to<br />

psychological distress.” This dimension is<br />

often termed emotional stability, which is the<br />

opposite of neuroticism, <strong>and</strong> includes facets<br />

such as hostility, depression, <strong>and</strong> anxiety.<br />

“The tendency to act in a cooperative,<br />

unselfish manner, construed as one end of a<br />

dimension of individual differences<br />

(agreeableness vs. disagreeableness) in the<br />

Big Five personality model.” This dimension<br />

includes facets such as trust <strong>and</strong> compliance.<br />

“An orientation of one’s interests <strong>and</strong> energies<br />

toward the outer world of people <strong>and</strong> things<br />

rather than the inner world of subjective<br />

experience. Extraversion is a broad<br />

personality trait <strong>and</strong>, like introversion, exists<br />

NEO-PI-R (Costa &<br />

McCrae, 1992); Big Five<br />

Inventory (John &<br />

Srivastava)<br />

Typical Intellectual<br />

Engagement (TIE,<br />

Ackerman); Need for<br />

Cognition (Cacioppo);<br />

Openness domain of any<br />

Big Five questionnaire<br />

Conscientiousness domain<br />

of any Big Five<br />

questionnaire<br />

Neuroticism domain of any<br />

Big Five questionnaire.<br />

Negative affect measures<br />

could also be used but the<br />

latter often emphasize<br />

temporary affect rather than<br />

dispositional affect.<br />

Agreeableness domain of<br />

any Big Five questionnaire.<br />

Extraversion domain of any<br />

Big Five questionnaire.

Social vitality<br />

Social dominance<br />

Need for<br />

Achievement/Ambition<br />

Delay of<br />

gratification/Impulsivity/Self-<br />

Control/Time Preference<br />

Sensation Seeking<br />

Perceived Self-efficacy/locus of<br />

control/optimism<br />

on a continuum of attitudes <strong>and</strong> behaviors.<br />

Extroverts are relatively more outgoing,<br />

gregarious, sociable, <strong>and</strong> openly expressive.”<br />

Roberts (2006) suggests that there are two<br />

aspects of Extraversion: social dominance <strong>and</strong><br />

social vitality. See below.<br />

A subdimension of Big Five Extraversion<br />

proposed by Roberts (2006) that includes<br />

facets such as sociability, positive effect, <strong>and</strong><br />

gregariousness.<br />

A subdimension of Big Five Extraversion that<br />

includes facets such as dominance,<br />

independent, <strong>and</strong> self-confidence, especially<br />

in social settings.<br />

“A strong desire to accomplish goals <strong>and</strong><br />

attain a high st<strong>and</strong>ard of performance <strong>and</strong><br />

personal fulfillment. People with high need for<br />

achievement undertake tasks in which there is<br />

a reasonable probability of success <strong>and</strong> avoid<br />

tasks that are too easy or too difficult”<br />

A facet of Big Five Conscientiousness. Desire<br />

to achieve difficult goals or reach high<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards.<br />

“forgoing immediate reward in order to obtain<br />

a larger or more desirable reward in the<br />

future”<br />

A facet of either Neuroticism or<br />

Conscientiousness. When faced with a choice<br />

between immediate temptation <strong>and</strong> superior,<br />

deferred gratification, the ability to control<br />

behavior, attention, <strong>and</strong> thoughts in order to<br />

attain superior, deferred reward.<br />

“The tendency to search out <strong>and</strong> engage in<br />

thrilling activities as a method of increasing<br />

stimulation <strong>and</strong> arousal. It takes the form of<br />

engaging in highly stimulating activities<br />

accompanied by a perception of danger.” A<br />

facet of either Conscientiousness or<br />

Extraversion. Attraction to novel, intense<br />

experiences <strong>and</strong> willingness to take risks for<br />

them.<br />

Perceived Self Efficacy: “Subjective<br />

perception of own capability of performance<br />

or ability to attain results”. Locus of Control:<br />

“perception of how much control individuals<br />

have over conditions of their lives”. Possibly a<br />

facet of Neuroticism. The belief that one has<br />

control over outcomes. The opposite of<br />

helplessness.<br />

CPI Sociability Scale; NEO-<br />

PI-R Gregariousness <strong>and</strong><br />

Activity Scales<br />

NEO-PI-R Assertiveness<br />

scale; 16PF Dominance<br />

Scale<br />

Projective measures<br />

(unreliable),<br />

Conscientiousness subscales<br />

Marshmallow task<br />

(Mischel); UPPS Impulsive<br />

Behavior Subscale<br />

(Whiteside & Lynam); Self-<br />

Control Scale (Baumeister);<br />

Time Perspective Inventory<br />

(Zimbardo)<br />

Sensation-seeking Scale<br />

Generalized self-efficacy<br />

scales 41 , Rotter Locus of<br />

Control Scale, Attributional<br />

Style Questionnaire<br />

41 B<strong>and</strong>ura does not endorse any trait-level scales<br />

1

Regulatory Focus<br />

Affect, Well-Being<br />

Self-esteem<br />

Temperament (childhood)<br />

Psychopathology<br />

Orientation toward either promotion of<br />

positive outcomes or prevention of negative<br />

outcomes.<br />

Positive affect is the internal feeling state that<br />

occurs when a goal has been attained, a source<br />

if threat has been avoided or the individual is<br />

satisfied with the present state of affairs”<br />

Positive affect includes emotions such as joy,<br />

contentment, <strong>and</strong> pride. Negative effect,<br />

which is only moderately inversely correlated<br />

with positive effect, includes fear, anxiety,<br />

sadness, etc. Life satisfaction is a cognitive,<br />

not affective, appraisal of the quality of one’s<br />

life. Well-being is characterized by the<br />

presence of positive effect, the absence of<br />

negative effect, <strong>and</strong> positive life satisfaction.<br />

“The degree to which the qualities <strong>and</strong><br />

characteristics contained in one’s self concept<br />

are perceived to be positive”<br />

One's estimation of one's own self-worth. A<br />

construct that enjoyed tremendous popularity<br />

in the 1970ss but since has been considered<br />

epiphenomenal not causal. A minority of<br />

psychologists consider positive <strong>and</strong> negative<br />

evaluations of the self to be the sixth <strong>and</strong><br />

seventh factors of personality. Possibly<br />

grouped with self-efficacy, etc.<br />

“Basic foundation of personality, usually<br />

assumed to be biologically determined <strong>and</strong><br />

present early in life[…] Includes<br />

characteristics such as energy level, emotional<br />

responsiveness, response tempo <strong>and</strong><br />

willingness to explore”<br />

Precursors to personality traits, temperament<br />

variables are patterns in behavior or affect that<br />

appear early in life that are assumed to have a<br />

neurobiological basis. There are fewer<br />

temperament variables than personality traits<br />

because these individual differences are less<br />

salient <strong>and</strong> stable in children than in adults.<br />

“Patterns of behavior or thought processes<br />

that are abnormal or maladaptive”. A broad<br />

category comprising dysfunctional patterns of<br />

thought, feeling, or behavior. Most disorders<br />

are included in the DSM-IV manual. Axis I<br />

disorders (e.g., depression) are more intense<br />

<strong>and</strong> episodic/discreet, whereas Axis II<br />

disorders (i.e., personality disorders) are more<br />

tonic <strong>and</strong> enduring.<br />

Regulatory Focus<br />

Questionnaire (Higgins et<br />

al., 2001)<br />

PANAS (Watson, Clark, &<br />

Tellegen) for positive <strong>and</strong><br />

negative affect; SWLS<br />

(Diener) for life satisfaction<br />

Rosenberg Self-Esteem<br />

Scale<br />

Children's Behavior<br />

Questionnaire<br />

Beck Depression Inventory;<br />

Beck Anxiety Inventory;<br />

MMPI (omnibus measure);<br />

Child Behavior Checklist<br />

(Achenbach)<br />

2

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator<br />

(MPTI)<br />

Type A/Type B personality<br />

Intelligence, General Mental<br />

Ability, “g”, IQ<br />

Specific mental abilities<br />

Creativity<br />

“A personality test designed to classify<br />

individuals according to their expressed<br />

choices between contrasting alternatives in<br />

certain categories of traits. The categories,<br />

based on Jungian typology, are extraversion-<br />

Introversion, Sensing-Intuition, Thinking-<br />

Feeling, <strong>and</strong> Judging-Perceiving…The test has<br />

little credibility among research psychologists<br />

but is widely used in educational counseling<br />

<strong>and</strong> human resource management…”<br />

Type A personality is “a personality pattern<br />

characterized by chronic competitiveness,<br />

high levels of achievement motivation, <strong>and</strong><br />

hostility.” Type B personality is “a personality<br />

pattern characterized by low levels of<br />

competitiveness <strong>and</strong> frustration <strong>and</strong> a relaxed,<br />

easy going approach.”<br />

Intelligence <strong>and</strong> general mental ability both<br />

refer to “the ability to derive information,<br />

learn from experience, adapt to the<br />

environment, underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> correctly utilize<br />

thought <strong>and</strong> reason.” “g” (“general factor”)<br />

refers to the first factor extracted from a factor<br />

analysis of cognitive tasks, which many<br />

researchers consider to represent general (vs.<br />

specific) intelligence.”It represents<br />

individuals’ abilities to perceive relationships<br />

<strong>and</strong> to derive conclusions from them. It is the<br />

basic ability that underlies the performance of<br />

different intellectual tasks”<br />

“ Intelligence quotient (IQ) refers to one’s<br />

intelligence relative to one’s age group<br />

(especially for children) but can also be used<br />

synonymously with intelligence.<br />

“<strong>Abilities</strong> as measured by tests of an<br />

individual in areas of spatial visualization,<br />

perceptual need, number facility, verbal<br />

comprehension, word fluency, memory,<br />

inductive reasoning <strong>and</strong> so forth”<br />

An umbrella category for lower-level mental<br />

abilities, including math, verbal, <strong>and</strong> spatial<br />

abilities, as well as even more specific mental<br />

capacities. 42<br />

“Ability to produce original work, theories,<br />

techniques or thoughts […] Related with<br />

imagination, expressiveness, originality.”<br />

Ability to generate novel ideas <strong>and</strong> behaviors<br />

that solve problems.<br />

MBTI<br />

WISC, WAIS, Raven’s<br />

Progressive Matrices,<br />

ASVAB<br />

Subtest scores on IQ tests<br />

Creative <strong>Personality</strong> Scale<br />

(Gough, 1979)<br />

42 Cattell considered fluid (capacity to learn) <strong>and</strong> crystallized intelligence (knowledge) to be second-order aspects of<br />

intelligence.<br />

3

Executive Function<br />

Cognitive reflection<br />

Emotional Intelligence<br />

“Higher level cognitive processes that<br />

organize <strong>and</strong> order behavior, including logic<br />

<strong>and</strong> reasoning, abstract thinking, problem<br />

solving, planning <strong>and</strong> carrying out <strong>and</strong><br />

terminating goal directed behavior” Broad set<br />

of higher-level cognitive capacities attributed<br />

to the prefrontal cortex, often involving the<br />

coordination <strong>and</strong> management of lower-level<br />

processes.<br />

A specific mental ability. The tendency to<br />

reflect before taking an intuitive answer as<br />

correct.<br />

“Ability to process emotional information <strong>and</strong><br />

use it in reasoning <strong>and</strong> other cognitive<br />

activities. According to Mayer <strong>and</strong> Slovey<br />

1997 model it comprises four abilities: to<br />

perceive <strong>and</strong> appraise emotions accurately, to<br />

access <strong>and</strong> evoke emotions when they<br />

facilitate cognition, to comprehend emotional<br />

language <strong>and</strong> make use of emotional<br />

information, <strong>and</strong> to regulate one’s own <strong>and</strong><br />

others’ emotions to promote growth <strong>and</strong> wellbeing”<br />

Ability to perceive emotion, to<br />

integrate it in thought, to underst<strong>and</strong> it <strong>and</strong> to<br />

manage it (Mayer)<br />

Innumerable<br />

neuropsychology tasks (e.g.,<br />

go/no-go, Stroop,<br />

Continuous Performance<br />

Task)<br />

Cognitive Reflection Test<br />

(Frederick, 2005)<br />

MSCEIT (Mayer &<br />

Salovey) but really there are<br />

no good measures<br />

Motivation – What individuals want to do, feel, or think<br />

“A moral, social or aesthetic principle<br />

accepted by an individual (or society) as a<br />

guide to what is good, desirable or important.”<br />

What individuals feel is important in a moral<br />

Values<br />

sense.<br />

“Attitude characterized by a need to give<br />

selective attention to something that is<br />

significant to the individual”.<br />

What spontaneously attracts <strong>and</strong> holds one’s<br />

Interests<br />

attention, <strong>and</strong> is considered pleasant.<br />

Goal: “The end state toward which a human is<br />

striving” Motive:”physiological or<br />

psychological state of arousal that directs an<br />

organism’s energies toward a goal”.<br />

What individuals aim to achieve or<br />

experience. Examples include need for<br />

power, need for affiliation, <strong>and</strong> need for<br />

achievement. Note that many consider need<br />

Goals, Needs, Motives for achievement as an aspect of personality.<br />

Values in Action Inventory<br />

of Strengths<br />

Self-Directed Search, Strong<br />

Interest Inventory<br />

Thematic Apperception Test<br />

(TAT), need for<br />

achievement questionnaires<br />

4

Figure 1<br />

Problem similar to the Raven’s Progressive Matrices test items<br />

Note: The bottom right entry of this 3x3 matrix of figures is missing <strong>and</strong> must be selected<br />

from among 8 alternatives. Looking across the rows <strong>and</strong> down the columns, the test taker<br />

attempts to determine the underlying pattern <strong>and</strong> then pick the appropriate missing piece.<br />

The correct answer to this problem is 5. Figure taken from Carpenter, Just, <strong>and</strong> Shell<br />

(1990), used with permission of the publisher, copyright American Psychological<br />

Association.

Measurement Error Can Create the Illusion of Multiple Factors when Only One is<br />

Operative<br />

If some outcome Y<br />

j<br />

is predicted by f k<br />

, <strong>and</strong> there are multiple mismeasured<br />

proxies for f<br />

k<br />

, those proxies will be predictive for Y<br />

j<br />

even though only one factor<br />

generates the outcome. Thus, if the following relationship holds between Y j <strong>and</strong> f k , where<br />

U<br />

j<br />

is statistically independent of f<br />

k<br />

,<br />

Y f U ,<br />

j k j<br />

<strong>and</strong> we use N Q-adjusted proxies for f<br />

k<br />

n<br />

n n n n<br />

M M ( Q)<br />

f <br />

k k k k k k<br />

n<br />

where <br />

k<br />

is independent of f k<br />

, has mean zero <strong>and</strong> variance<br />

n<br />

means of the measures to depend on Q ( ( Q))<br />

, we obtain an equation<br />

k<br />

N<br />

n<br />

Y <br />

j<br />

nM k U<br />

j ,<br />

n1<br />

<br />

2<br />

n<br />

k<br />

, where we allow the<br />

where U j <br />

fk U<br />

j<br />

<strong>and</strong> where the true values of <br />

n<br />

are all zero, because the test scores<br />

do not determine Y<br />

j<br />

but instead f<br />

k<br />

determines it unless 0 . Straightforward<br />

calculations show that under general conditions, if one arrays the <br />

n<br />

in a vector of length<br />

N, γ N , <strong>and</strong> the Q-adjusted test scores in a vector of length N, denoted M , the OLS<br />

estimator<br />

<br />

N<br />

1<br />

<br />

<br />

Cov M, M Cov M , Y n<br />

<br />

converges in large samples to

2<br />

2 1 2 1 2 2 1 N 2<br />

1 k <br />

f<br />

<br />

k kk f<br />

<br />

k kk <br />

f<br />

k<br />

k<br />

<br />

1<br />

1 2 2 2 2<br />

2<br />

2<br />

<br />

<br />

k<br />

N<br />

2<br />

<br />

2<br />

kk <br />

f<br />

<br />

k<br />

k<br />

<br />

<br />

fk<br />

plim <br />

<br />

<br />

k<br />

f<br />

.<br />

k<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

k<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

N <br />

1 L 2 2 N<br />

2<br />

2<br />

<br />

kk <br />

f<br />

<br />

N <br />

k<br />

k<br />

<br />

f<br />

<br />

k<br />

k <br />

1<br />

Assuming<br />

2<br />

0,<br />

0<br />

<strong>and</strong> 0 , for all n1, , N , any error-ridden predictor of<br />

2<br />

f k<br />

n<br />

k<br />

f<br />

k<br />

will be statistically significant in a large enough sample. Using a purely predictive<br />

criterion to determine personality traits produces a proliferation of “significant”<br />

predictors for outcome Y<br />

j<br />

, as is found in the psychological studies that we survey in the<br />

text. Cunha <strong>and</strong> Heckman (this issue) show that estimated measurement errors in both<br />

cognitive <strong>and</strong> noncognitive tests are important so that the problem of proxy proliferation<br />

using a predictive criterion is serious. Under such a criterion, many “significant”<br />

predictors of an outcome can be found that are all proxies for a single latent construct.<br />

If, in addition to these considerations, the measures fail discriminant validity, the<br />

predictors for one outcome may proxy both f<br />

k<br />

<strong>and</strong> f k<br />

k<br />

k<br />

if f<br />

k<br />

<strong>and</strong> f k<br />

are<br />

correlated. We present evidence in the text, Section III, that IQ tests proxy both cognitive<br />

<strong>and</strong> personality factors. A purely predictive criterion fails to distinguish predictors for<br />

clusters associated with the f<br />

k<br />

from predictors for clusters proxying the fk<br />

. Thus, items<br />

in one cluster can be predictive of outcomes more properly allocated to another cluster.<br />

Accounting for Reverse Causality<br />

A test score may predict an outcome because the outcome affects the test score.<br />

Hansen, Heckman, <strong>and</strong> Mullen (2004) analyze a model in which, in the previous<br />

representation, the outcome being related to cluster (factor) k, say Y<br />

j<br />

, is an element of Q

n<br />

n<br />

<strong>and</strong> determines <br />

k<br />

( Q)<br />

<strong>and</strong> <br />

k<br />

( Q)<br />

. In addition, they allow (factor) f<br />

k<br />

to be a<br />

determinant of Y<br />

j<br />

. They establish conditions under which it is possible to identify causal<br />

effects of f<br />

k<br />

on Y<br />

j<br />

when the proxies for f<br />

k<br />

suffer from the problem of reverse causality<br />

n<br />

n<br />

because the Q in ( Q)<br />

<strong>and</strong> ( Q)<br />

may include Y<br />

j<br />

among its components. They<br />

k<br />

k<br />

establish that tests of cognitive ability (e.g., AFQT) are substantially affected by<br />

schooling levels at the date the test is taken.<br />

To underst<strong>and</strong> how their method works at an intuitive level, consider the effect of<br />

schooling on measured test scores. Schooling attainment likely depends on true or<br />

“latent” ability, f<br />

k<br />

. At the same time, the measured test score depends on schooling<br />

n<br />

n<br />

attained so it affects ( Q)<br />

or ( Q)<br />

or both. Hansen, Heckman, <strong>and</strong> Mullen (2004)<br />

k<br />

k<br />

assume access to longitudinal data that r<strong>and</strong>omly sample the population. Included in the<br />

sample are adolescents. At the time the adolescents are given the test, persons who<br />

eventually attain the same schooling level are at different grade levels at the date of the<br />

test because the longitudinal sample includes people of different ages <strong>and</strong> schooling<br />

levels. From the longitudinal data we can determine final schooling levels. Final<br />

schooling levels are assumed to depend on latent ability f k<br />

. Conditional on the final<br />

schooling level attained, schooling levels at the date of the test are r<strong>and</strong>om with respect to<br />

f<br />

k<br />

because the sampling rule is r<strong>and</strong>om across ages at a point in time. One can identify<br />

the causal effect of schooling on test scores from the effect of variation in the years of<br />

education attained at the date of test on test scores for persons who attain the same final<br />

schooling level. See Hansen, Heckman, <strong>and</strong> Mullen (2004) for additional details on this<br />

method <strong>and</strong> alternative identification strategies. The basic idea of their procedure is to

model the dependence between Q <strong>and</strong> f<br />

k<br />

<strong>and</strong> to solve the problem of reverse causality<br />

using this model. Heckman, Stixrud <strong>and</strong> Urzua (2006) develop this method further.<br />

Cunha <strong>and</strong> Heckman (2007) <strong>and</strong> Cunha, Heckman <strong>and</strong> Schennach (2006) extend this<br />

procedure to allow f<br />

k<br />

to evolve over time through investment <strong>and</strong> experience.

a) <strong>Personality</strong><br />

a1. “BIG FIVE”:<br />

The literature on personality psychology widely adopts “the big five” as a taxonomy for describing one’s<br />

personality traits.<br />

The idea is that there are five big dimensions over which personality can be studied. These dimensions are<br />

openness to experience, conscientiousness, neuroticism, agreeableness <strong>and</strong> extraversion.<br />

Each dimension is then subdivided in lower level traits called “facets”. While there is a relatively broad<br />

consensus over the big five, there is still a wide disagreement over which facets correspond to each<br />

dimension. In the present scheme, we propose one of the possible lower order structure.<br />

Measures for the big five:<br />

- Big Five Inventory, 44 items questionnaire at page 70 of John O., Srivastava S., (1999): “The Big Five<br />

Traits Taxonomy: History, Measurement, <strong>and</strong> Theoretical Perspectives”:<br />

http://www.uoregon.edu/~sanjay/pubs/bigfive.pdf<br />

- NEO-PI-R (Costa, McCrae, 1992), 240 items. It measures not only the Big Five, but also six "facets" of<br />

each of the Big Five. Commercial product not publicly available. See<br />

http://www3.parinc.com/products/product.aspx?Productid=NEO-PI-R<br />

- NEO FFI, 60 items only measuring the big five. Also not publicly available.<br />

http://www3.parinc.com/products/product.aspx?Productid=NEO-SS_PIR-FFI<br />

For a general introductory literature on the “big five”:<br />

- Costa P., McCrae R. (1999), “A five factors model of personality”, H<strong>and</strong>book of <strong>Personality</strong>, Theory<br />

<strong>and</strong> research, Guilford Press, New York.<br />

- Digman J., (1990) “<strong>Personality</strong> Structure: Emergency of the Five factor model”, Annual Review of<br />

Psychology 41, 417-440<br />

- Goldberg L.R., (1990), “An alternative description of personality: the big five factor structure”, Journal<br />

of <strong>Personality</strong>, 59(6), 1216-1229<br />

- John O., Srivastava S., (1999), “The big five trait taxonomy: history, measurement <strong>and</strong> Theoretical<br />

Perspectives”, 102-139 in “H<strong>and</strong>book of personality: Theory <strong>and</strong> research”, Guilford Press, New York.<br />

- John O., (1989) “Towards a taxonomy of <strong>Personality</strong> Descriptors”, in Buss <strong>and</strong> Cantor Eds, <strong>Personality</strong><br />

Psychology: Recent trends <strong>and</strong> Emerging Directions”, 261-271, Springer, NY.<br />

- John O., Goldber L.R., (1991)” Is there a level of personality description?”, Journal of <strong>Personality</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

Social Psychology 60, 348-361<br />

- Srivastava, S. (2006). Measuring the Big Five <strong>Personality</strong> Factors. Retrieved from<br />

http://www.uoregon.edu/~sanjay/bigfive.html<br />

For a discussion of facets:<br />

- Costa, McCrae,Dye,(1992). “Facet scales for agreeableness <strong>and</strong> conscientiousness: A revision of the<br />

NEO <strong>Personality</strong> Inventory”. <strong>Personality</strong> <strong>and</strong> Individual Differences, 12, 887-898.<br />

- Costa, McCrae (1995): “Domains <strong>and</strong> facets: Hierarchical <strong>Personality</strong> Assessment using the revised<br />

NEO PI”, Journal of <strong>Personality</strong> Assessment 64, 21-50<br />

For further readings on the links between big five <strong>and</strong> smoking, crime, scholastic achievement <strong>and</strong><br />

labor market outcomes.:<br />

1) on smoking <strong>and</strong> alcohol use:<br />

- T. Trull , C. Waudby, K. Sher K. (2004): “ Alcohol, Tobacco <strong>and</strong> Drug use disorders <strong>and</strong> personality<br />

disorder symptoms” Experimental <strong>and</strong> Clinical Psychopharmacology 12 (1), 65-75; for a review.<br />

5

- Zuckermann M., (1993) “Behavioral expression <strong>and</strong> biosocial bases of sensation seeking” New York,<br />

Cambridge University Press<br />

2) on crime<br />

- Gottfredson <strong>and</strong> Hirschi 1990, “ A General Theory of Crime”, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press;<br />

on relationship between self control <strong>and</strong> crime<br />

- Schaeffer C., Petras H., Ialongo N., Poduscka J., Kellman S., (2003), “Modeling Growth in Boys’<br />

Aggressive Behavior Across Elementary School: Links to Later Criminal Involvement, Conduct<br />

Disorder <strong>and</strong> Antisocial <strong>Personality</strong> Disorder” Developmental Psychology 39 (6): 1020-1035; on<br />

relationship between aggression <strong>and</strong> crime<br />

3) on scholastic achievement<br />

- Borghans L., Meijers H. <strong>and</strong> Ter Weel B., (2006), “The role of non cognitive skills in explaining non<br />

cognitive test scores” Maastricht University working paper, Maastricht, the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

- Duckworth A., Seligman M.(2005),” Self Discipline outdoes IQ in predicting Academic Performance in<br />

Adolescents” Psychological Science 16, 934-944; on self control <strong>and</strong> scholastic achievement<br />

- Noftle <strong>and</strong> Robins, in press. I can’t find it!<br />

- Wolfe R. <strong>and</strong> Johnson S., (1995), “<strong>Personality</strong> as a Prediction of College Performance”, Educational <strong>and</strong><br />

Psychological Measurement, 55 (2), 177-185<br />

4) on labor market performance<br />

- Barrick, Mount, (1991) “ The big five personality dimensions <strong>and</strong> job performance”, Personnel<br />

Psychology, Blackwell Synergy.<br />

- Roberts B., Wood D., Smith J.(2005) “Evaluating Five Factor Theory <strong>and</strong> Social Investment<br />

Perspectives on <strong>Personality</strong> Trait Development”, Journal of Research on <strong>Personality</strong> 39: 166-184<br />

- Barrick, Higgins, Murray, Chad, Judge, Thoresen (1999) “The Big Five <strong>Personality</strong> Traits, General<br />

Mental Ability <strong>and</strong> Career Success across the Life Span”, Personnel Psychology, 52<br />

Roberts, B. W., & Robins, R. W. (2000). Broad dispositions, broad aspirations: The intersection of the<br />

Big Five dimensions <strong>and</strong> major life goals. <strong>Personality</strong> <strong>and</strong> Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1284-1296.<br />

- Roberts, B. W., & Robins, R. W. (2004). A longitudinal study of person-environment fit <strong>and</strong><br />

personality development”. Journal of <strong>Personality</strong>, 72, 89-110.<br />

DOMAINS OF THE BIG FIVE:<br />

1. Openness to experience<br />

“A dimension of the Big Five personality model that refers to individual differences in the tendency to<br />

be open to new aesthetic, cultural, or intellectual experiences.” (APA Dictionary)<br />

It is the Big Five domain that correlates most with IQ (r about .3). It is also called Intellect. Includes<br />

facets such as open-mindedness, creativity, appreciation of arts <strong>and</strong> music.<br />

For its correlation with openness to experience, authors include into this category also J. Cacioppo’s<br />

need for cognition concept: an individual's tendency to engage in <strong>and</strong> enjoy effortful cognitive<br />

endeavours. For a measure of need for cognition see the 18 items questionnaire at Cacioppo, Kao,<br />

Petty (1984), - http://www.leaonline.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_13.<br />

Another measure related to openness to experience is the TIE, Typical Intellectual Engagement (see<br />

Ackerloff <strong>and</strong> Goff, 1992, 1994)<br />

For readings on Openness to Experience:<br />

- Cacioppo, Kao, Petty, (1984), “An efficient assessment for need for cognition”, Journal of <strong>Personality</strong><br />

Assessment, 48 (3) http://www.leaonline.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_13<br />

- Elias, Loomis (2002) : Utilizing Need for Cognition <strong>and</strong> Perceived Self-Efficacy to Predict Academic<br />

Performance, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32 (8), 1687–1702.<br />

- Goff, Ackerman, (1992), “Typical Intellectual Engagement (TIE) measure”, Journal of Educational<br />

Psychology 84(4), December 1992, 537–552<br />

2. Conscientiousness<br />

“The tendency to be organized, responsible, <strong>and</strong> hardworking, construed as one end of a dimension of<br />

individual differences (conscientiousness vs. lack of direction) in the Big Five personality model.”<br />

(APA Dictionary)<br />

Conscientiousness is the Big Five domain that best predicts work <strong>and</strong> health outcomes.<br />

6

Most of the work on conscientiousness is done by Brent Roberts. His website link below is a good<br />

source for further readings.<br />

Two well studied facets empirically related to conscientiousness are need for achievement <strong>and</strong> delay<br />

for gratification.<br />

- Need for achievement is defined as “A strong desire to accomplish goals <strong>and</strong> attain a high st<strong>and</strong>ard of<br />

performance <strong>and</strong> personal fulfillment. People with high need for achievement undertake tasks in which<br />

there is a reasonable probability of success <strong>and</strong> avoid tasks that are too easy or too difficult”<br />

- while Delay for gratification is the ability of foregoing immediate reward in order to obtain a larger or<br />

more desirable reward in the future” (APA Dictionary)<br />

The “Marshmallow test” (Mischel 1989) was the first study of the relationship between delayed<br />

gratifications <strong>and</strong> outcomes later in life. See literature below. There is no single measure for delay of<br />

gratification.<br />

As for need for achievement, it is usually measured by McClell<strong>and</strong> N-Ach Tematic Apperception Test<br />

(TAT), a projective test that however has come under serious critique from mainstream psychology.<br />

For readings on Conscientiousness<br />

- Brent Roberts papers on conscientiousness are available at his<br />

website,http://www.psych.uiuc.edu/~broberts/Brent%20W%20Roberts%20Research%20Interests.htm<br />

- Need for Achievement:<br />

- McClell<strong>and</strong>, D.C. (1961) The achieving society. Princeton: Van Nostr<strong>and</strong>.<br />

- McClell<strong>and</strong>, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., & Lowell, E. L. (1958). A scoring manual for the<br />

achievement motive; in J. W. Atkinson (Ed.), Motives in Fantasy, Action <strong>and</strong> Society. New York: Van<br />

Nostr<strong>and</strong>.<br />

- Costa <strong>and</strong> McCrae, (1992) “ NEO PI-R professional manual”. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment<br />

Resources, Inc.<br />

- Delay of Gratification:<br />

- Mischel, Shoda, Rodriguez,. (1989). “Delay of gratification in children”. Science, 244, 933-938.<br />

- Funder, Block (1989) “The role of Ego-Control, Ego-Resiliency <strong>and</strong> IQ Delay of Gratification in<br />

Adolescence”. Journal of <strong>Personality</strong> <strong>and</strong> Social Psychology, 57(6), 1041–1050. A delay gratification<br />

experiment with 14 years old adolescent, evidence that delay behaviour is related with IQ.<br />

- Self Control:<br />

- Roy Baumesteir at http://www.psy.fsu.edu/~baumeistertice/<br />

3. Neuroticism<br />

Neuroticism is “characterized by a chronic level of emotional instability <strong>and</strong> proneness to psychological<br />

distress.” (APA Dictionary)<br />

It describes the tendency to feel negative emotions, such as anxiety, fear, sadness, <strong>and</strong> hostility,<br />

particularly when under stress.<br />

Facets empirically loading on neuroticism are self efficacy <strong>and</strong> locus of control. Although some<br />

literature considers these measures as independent traits of personality, they are much correlated with<br />

each other (with a correlation of about r=.6), as they both refer to the belief to have outcomes under<br />

control. Perceived Self Efficacy (B<strong>and</strong>ura, A.) is the “Subjective perception of own capability of<br />

performance or ability to attain results”. Self Efficacy is case dependent (one can have highs elf efficacy<br />

in one field but low in another). It is emphasized that self efficacy is different from ability. For example,<br />

some studies have documented that, given ability, girls have lower measure of self efficacy than boys<br />

(Pajares, 1996, among others). Locus of Control is the “perception of how much control individuals<br />

have over conditions of their lives”.<br />

Locus of Control can be internal or external. If internal, the individual attributes events to his own<br />

control: success or insuccess is a consequence of his or her actions. If external, the individual believes<br />

instead that outcomes are a consequence of good or bad luck.<br />

Measures for perceived self efficacy <strong>and</strong> locus of control:<br />

Perceived Self efficacy:<br />

B<strong>and</strong>ura does not endorse <strong>and</strong> trait specific scales, but generalized self efficacy scales can be found into<br />

the “Self Efficacy Measures” paragraph of the website on self efficacy:<br />

http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/self-efficacy.html<br />

Locus of Control:<br />

7

Rotter has a 29 items questionnaire to measure locus of control, available at<br />

http://wilderdom.com/psychology/loc/RotterLOC29.html<br />

For a measure of optimism: Seligman M., Abramson L., Semmel A., von Baeyer C., Peterson C.:<br />

“Attributional Style Questionnaire: description <strong>and</strong> assessment”, Cognitive Therapy 6(3), 287-299.<br />

http://www.springerlink.com.proxy.uchicago.edu/content/t372377276jp6636/?p=aded4ffddd064fe8be8<br />

3883d5bb91b78&pi=4<br />

For reading on the facets of self efficacy <strong>and</strong> locus of control:<br />

- B<strong>and</strong>ura A., 1977, “Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change”<br />

Psychological Review, 84 (2), 191-215<br />

- All of B<strong>and</strong>ura’ publications can be found in his website: http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/banpubs.html<br />

- Website on self efficacy: http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/self-efficacy.html<br />

- Rotter, J.B. (1966). "Generalized expectancies of internal versus external control of reinforcements".<br />

- Judge, Bono, Thoresen (2002), “Are Measures of Self-Esteem, Neuroticism, Locus of Control, <strong>and</strong><br />

Generalized Self-Efficacy Indicators of a Common Core Construct?” Journal of <strong>Personality</strong> <strong>and</strong> Social<br />

Psychology, 83(3)<br />

4. Agreeableness<br />

“The tendency to act in a cooperative, unselfish manner, construed as one end of a dimension of<br />

individual differences (agreeableness vs. disagreeableness) in the Big Five personality model.” This<br />

dimension includes facets such as trust <strong>and</strong> compliance. (APA Dictionary)<br />

5. Extraversion<br />

“An orientation of one’s interests <strong>and</strong> energies toward the outer world of people <strong>and</strong> things rather than<br />

the inner world of subjective experience. Extraversion is a broad personality trait <strong>and</strong>, like introversion,<br />

exists on a continuum of attitudes <strong>and</strong> behaviors. Extroverts are relatively more outgoing, gregarious,<br />

sociable, <strong>and</strong> openly expressive.” (APA dictionary)<br />

Roberts (2006) suggests that there are two aspects of Extraversion: Social Dominance <strong>and</strong> Social<br />

Vitality.<br />

- Social Dominance: describes dominance, independent, <strong>and</strong> self-confidence, especially in social<br />

settings. See NEO PI for a measure.<br />

- Social Vitality: describes sociability, positive effect, <strong>and</strong> gregariousness. See NEO PI <strong>and</strong> CPI<br />

(California Psychological Inventory) sociability scale for a measure.<br />

A third facet is empirically related to both extraversion <strong>and</strong> conscientiousness:<br />

- Sensation Seeking: “the tendency to search out <strong>and</strong> engage in thrilling activities as a method of<br />

increasing stimulation <strong>and</strong> arousal. It takes the form of engaging in highly stimulating activities<br />

accompanied by a perception of danger” (APA Dictionary). Zuckermann is the main author for<br />

sensation seeking: he is also the creator of a sensation seeking scale:<br />

- Zuckerman (1979) “Sensation seeking: beyond the optimal level of arousal”. Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum. The<br />

scale is online at<br />

http://www.rta.nsw.gov.au/licensing/tests/driverqualificationtest/sensationseekingscale/<br />

Zuckermann has recently published a book on sensation seeking <strong>and</strong> risky behaviour:<br />

- Zuckermann M. (2006) “Sensation Seeking <strong>and</strong> Risky Behavior”, Washington, DC : American<br />

Psychological Association.<br />

a2. POSITIVE AFFECT, WELL BEING AND HAPPINESS<br />

“Positive effect is the internal feeling state that occurs when a goal has been attained, a source if threat<br />

has been avoided or the individual is satisfied with the present state of affairs”<br />

Positive affect includes emotions like joy, contentment, <strong>and</strong> pride. Negative affect, which is only<br />

moderately inversely correlated with positive emotions, includes fear, anxiety, sadness, etc. Life<br />

satisfaction (Diener, Seligman) is a cognitive, not affective, appraisal of the quality of one’s life. Wellbeing<br />

is the presence of positive effect, the absence of negative <strong>and</strong> positive life satisfaction.<br />

Measures:<br />

8

- SWLS, “Satisfaction with life scale”, (Ed Diener). A 5 questions cognitive, not affective, appraisal of<br />

the quality of one’s life: http://www.psych.uiuc.edu/~ediener/hottopic/hottopic.html<br />

- PANAS, “Positive <strong>and</strong> Negative Affect Schedule” (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen) for positive <strong>and</strong><br />

negative effect. For presentation <strong>and</strong> for example of PANAS see:<br />

http://www.psychology.uiowa.edu/Faculty/Watson/PANAS-X.pdf<br />

Literature:<br />

- Websites, with links to publications:<br />

http://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu/<br />

http://www.centreforconfidence.co.uk/pp/contributors.php<br />

http://www.enpp.org/<br />

- Snyder, C. R., Lopez, S. J. (Eds.). H<strong>and</strong>book of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University<br />

Press.<br />

- Feldman Barrett L., Russell J., (1999), “The Structure of Current Affect: Controversies <strong>and</strong> Emerging<br />

Consensus”, Current Directions in Psychological Science 8 (1), 10–14.<br />

- Feldman Barrett L., Mesquita B., Ochsner K., Gross J., (2007) “The Experience of Emotion” Annual<br />

Review of Psychology 58:1, 373<br />

a3. SELF ESTEEM<br />

“The degree to which the qualities <strong>and</strong> characteristics contained in one’s self concept are perceived to<br />

be positive”<br />

Self-esteem is a positive or negative orientation toward oneself: an overall evaluation of one's worth or<br />

value<br />

It is a construct that enjoyed tremendous popularity in the 1970ss but since has been considered<br />

epiphenomenal not causal. A minority of psychologists consider positive <strong>and</strong> negative evaluations of<br />

the self to be the sixth <strong>and</strong> seventh factors of personality.<br />

It is measured with Self Esteem Rosemberg Scale. Link at:<br />

http://www.atkinson.yorku.ca/~psyctest/rosenbrg.pdf<br />

Literature:<br />

- Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, Vohs, (2003). “Does High Self-esteem Cause Better Performance,<br />

Interpersonal Success, Happiness, or Healthier Lifestyles?” Psychological Science in the Public<br />

Interest, 4, 1-44. http://www.psy.fsu.edu/~baumeistertice/baumeisteretal2003.pdf<br />

- Robins R., Trzesniewski K., Moffit T., Caspi A., Donnellan B., Poulton R., (2006): “Low Self Esteem<br />

During Adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behaviour <strong>and</strong> limited economic prospects during<br />

adulthood” Developmental Psychology 42(2); in a different perspective than Bauemeister, Robins <strong>and</strong><br />

Trzesniewski work show evidence that self esteem does matter.<br />

a4. TEMPERAMENT (childhood)<br />

“Basic foundation of personality, usually assumed to be biologically determined <strong>and</strong> present early in<br />

life. It Includes characteristics such as energy level, emotional responsiveness, response tempo <strong>and</strong><br />

willingness to explore” (APA Dictionary)<br />

There are fewer temperament variables than personality traits because these individual differences are<br />

less salient <strong>and</strong> stable in children than in adults.<br />

After the pioneering work of Thomas <strong>and</strong> Chess (1977), different taxonomies have been proposed in the<br />

literature. A recent <strong>and</strong> very comprehensive is the one in Shiner R. And Caspi A. (2003) , which<br />

individuates four main domains in child personality:<br />

1)Extraversion/Positive Emotionality, with lower order traits of social inhibition, sociability,<br />

dominance <strong>and</strong> activity level. 2) Neuroticism/Negative Emotionality with lower traits of anxious<br />

distress (tapping fear <strong>and</strong> anxiety) <strong>and</strong> irritable distress (tapping anger <strong>and</strong> irritability).<br />

3)Conscientiousness/Constraints, with lower traits of attention, inhibitory control <strong>and</strong> achievement<br />

motivation. 4)Agreeableness<br />

Little is still known about how these early emerging differences evolve into personality traits.<br />

Measures:<br />

9

There are different typologies of measures for children personality. It should be emphasized that all of<br />

them have biases, <strong>and</strong> that therefore is always good to use more than one.<br />

The typologies are, as indicated in Shiner <strong>and</strong> Caspi (2003):<br />

1) Naturalistic observations (infants): Naturalistic observations are based on the direct observation of<br />

the child's behavior in naturalistic settings, such as the child's home environment. In this procedure,<br />

observers typically watch the child for periods of several hours <strong>and</strong> then use coding procedures for<br />

observing a variety of specific behavioral tendencies.<br />

The most used behavioural code is Eaton, Enns <strong>and</strong> Presse (1987), Journal of Psychoeducational<br />

Assessment 3, 273-280. The code is available on the article. Some rate the child's temperament across a<br />

variety of dimensions after the observation is completed, using one of the st<strong>and</strong>ard temperament<br />

questionnaires<br />

2) Questionnaires completed by parents or teachers (infants <strong>and</strong> children):<br />

These questionnaires mainly study temperament along the lines of the “big five”<br />

- IBQ (Infant Behavior Questionnaire): M. Rothbart<br />

- CBQ (Children behaviour Questionnaire): Rothbart M, Ahadi S., Hershey K., Fisher P., (2001) “ Child<br />

Development 72 (5), 1394-1408. The CBQ detected 15 primary temperament questionnaires, factor<br />

analysis individuates 3 main factors: 1) extraversion/Surgency 2) Negative Affectivity 3) Effortful<br />

Control. In appendix A of the paper there are scale definitions <strong>and</strong> sample items for CBQ.<br />

http://www.bowdoin.edu/~sputnam/rothbart-temperament-questionnaires/<br />

- ICID: Inventory Child Individual Differences: Halverson C., Havill V., Deal J. (2003):”<strong>Personality</strong><br />

Structure as derived from parental ratings of free descriptions of children: The Inventory of Child<br />

Individual Differences” , Journal of <strong>Personality</strong> 71 (3). Representative items of ICID are in the<br />

“Appendix A” of the article.<br />

- (HiPIC): Mervielde I., De Fruyt F. (1999): “Construction of the hierarchical personality inventory for<br />

Children” Hierarchical <strong>Personality</strong> Inventory for Children in Mervielde, Deary, DeFruyt,Ostendorf,<br />

<strong>Personality</strong> Psychology in Europe:Proceedings of the Eight European Conference on <strong>Personality</strong>, 107-<br />

127, Tillburg U Press.Couldn’t find the article on line.<br />

Principal component analyses at the item level indicated that, for each age level, the first five principal<br />

components tended to group items according to the Big Five. five domains: Conscientiousness,<br />

Benevolence, Extraversion, Imagination, <strong>and</strong> Emotional Stability.<br />

- Dutch BLIK: Slotboom, A., & Elphick, E. (1997). Parents’ perceptions of child personality:<br />

Developmental precursors of the Big Five. Alblasserdam, The Netherl<strong>and</strong>s:<br />

Haveka b. v.<br />

- Goldberg (2001):”Analyses of Digman’s child-personality data: Derivation of Big Five factor scores<br />

from each of six samples. Journal of <strong>Personality</strong>, 69, 709–744.Working on Digman data on Hawaiian<br />

children shows that the big five are derived as dimensions of personality of children.<br />

3) Q-Sets (children) : an informant (parents, teachers, observers or clinicians) sorts a set of cards into a<br />

quasi normal distribution based on how well each item describes the child. Also constructed along the<br />

“big five” taxonomy.<br />

The main two Q-Sets are:<br />

- California Child Q-Set: Block J., Block JH.(1969/1980): “The California Child Q-Set” Palo Alto, CA:<br />

Consulting Psychologists Press. Not publicly available. This Q-set consists of 100 cards; on each was a<br />

descriptive statement which parents rank-ordered into nine categories ranging from "most descriptive"<br />

to<br />

"least descriptive" of their child.<br />

- Common Language Q-set: Caspi A., Block J., Block JH., Klopp B., Lynam D., Moffit T., Stouthamer-<br />

Loeber M. (1992): “A ‘common language’ version of the California Child Q set for personality<br />

assessment” Psychological Assessment 4, 512-523. Represents the CCQset in a simpler language <strong>and</strong><br />

focuses especially on antisocial behavior. An example of the cards can be found at page. 520 of the<br />

article.<br />

4) Laboratory tasks (children):<br />

- Laboratory procedures (LAB-TAB: Goldsmith, Rothbart, 1993): contains measures such as<br />

Stranger Approach, Modified Peek-a-Boogame, <strong>and</strong> Puppet Game. In the lab, 20 episodes or games are<br />

used to elicit reactions of frustration (anger), wariness (fear), interest, pleasure, <strong>and</strong> activity level.<br />

10

- Preschool Lab-TAB (Goldsmith, Reilly, 1995):<br />

Information on both at:<br />

http://psych.wisc.edu/goldsmith/Researchers/GEO/lab_TAB.htm<br />

The LAB-TAB manual can be downloaded at:<br />

http://psych.wisc.edu/goldsmith/Researchers/GEO/Lab_TAB_download_info.htm<br />

Some of the studies using LAB-TAB:<br />

- Goldsmith, H. H., & Rieser-Danner, L. (1990). Assessing early temperament. In C. R. Reynolds & R.<br />

Kamphaus (Eds.), H<strong>and</strong>book of psychological <strong>and</strong> educational assessment of children. (vol. 2)<br />

<strong>Personality</strong>, behavior, <strong>and</strong> context. (pp. 345-378). New York: Guilford Press.<br />

- Goldsmith, H., Rieser-Danner, L., & Briggs, S. (1991). Evaluating convergent <strong>and</strong> discriminant validity<br />

of temperament questionnaires for preschoolers, toddlers, <strong>and</strong> infants. Developmental Psychology, 27,<br />

No. 4, 566-579.<br />

5) Peer Nominations (adolescents): the peer group nominates who is the best described by a particular<br />

item.<br />

- Mervielde I., Defruyt F. (2000):”The Big Five <strong>Personality</strong> Factors as a model for the structure of<br />

children’s peer nominations” European Journal of <strong>Personality</strong> 14, 91-106<br />

- Masten A., Morison P., Pellegrini D., (1985): “A revised class method of peer assessment”,<br />

Developmental Psychology 21, 523-533<br />

6) Self Reports (adolescents, only recently also children).<br />

- Vance H., Pumariega A. (2001):”Clinical Assessment of children <strong>and</strong> adolescents behaviour”, New<br />

York: Wiley.<br />

- Eder R.(1990): “Uncovering young children’s psychological selves: Individual <strong>and</strong> developmental<br />

differences” child Development 61, 849-863. New method for underst<strong>and</strong>ing children individual<br />

differences through self reports with a Puppet interview. The children are 4-8 years old, <strong>and</strong> the study<br />

shows consistency of traits after one month.<br />

Literature:<br />

- Crespi A., Shiner R. (2003) “<strong>Personality</strong> Differences in childhood <strong>and</strong> adolescence: measurement,<br />

development <strong>and</strong> consequences”, Journal of Psychology <strong>and</strong> Psychiatry 44(1), 2-32<br />

- Shiner, R. (2006), “Temperament <strong>and</strong> personality in childhood”. In D. K. Mroczek & T. Little (Eds.),<br />

H<strong>and</strong>book of personality development (pp. 213-230). Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum.<br />

- Shiner, R. (<strong>Personality</strong> Differences in Childhood <strong>and</strong> adolescence: measurement, development <strong>and</strong><br />

consequences”, Journal of Child Psychology <strong>and</strong> Psychiatry, 44 (1), 2003, p.2-32<br />

- Shiner R., Masten A., Roberts J.(2003). “Childhood personality foreshadows adult personality <strong>and</strong> life<br />

outcomes two decades later”. Journal of <strong>Personality</strong>, 71, 1145-1170. Special issue: <strong>Personality</strong><br />

development.<br />

- Thomas A., Chess S. (1977): “Temperament <strong>and</strong> Development” NY: Brunner/Mazel<br />

Jerry Kagan:<br />

- Kagan J., 1988, “Biological basis of childhood shyness”, Science, 240 (4849) , 167 - 171<br />

Mary Rothbart:<br />

- Rothbart, M. K. (1981). Measurement of temperament in infancy. Child Development, 52, 569-578.<br />

- Rothbart, M, Bates, J (1998)”Temperament”, in H<strong>and</strong>book of child psychology: Vol 3, Social,<br />

emotional <strong>and</strong> personality development, Damon Eisemberg Eds,<br />

a5. PSYCHOPATHOLOGY<br />

A broad category comprising dysfunctional patterns of thought, feeling, or behavior. Most disorders are<br />

included in the DSM-IV manual. Axis I disorders (e.g., depression) are more intense <strong>and</strong><br />

episodic/discreet, whereas Axis II disorders (i.e., personality disorders) are more tonic <strong>and</strong> enduring.<br />

Measure:<br />

For depression, the main scale is the Beck one. It indicates the acuteness of depression, but it is only for<br />

adults.<br />

- Beck, A., (1961) “An inventory for measuring depression “, Arch Gen Psychiatry, Archives of General<br />

Psychiatry 4, 561-571<br />

A version for kids is Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist:<br />

11

- http://www.aseba.org/products/forms.html<br />

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Check List/4–18 <strong>and</strong> 1991 Profile. Burlington:<br />

University of Vermont.<br />

- Another measure of Psychopathology is the Child Depression Index, which can be found in PSID.<br />

Literature:<br />

- Seligman, M.E.P., Walker, E., & Rosenhan, D.L. (2001). Abnormal psychology. (4th ed.) New York:<br />

W.W. Norton. Manual in Abnormal Psychology.<br />

- “Diagnostic <strong>and</strong> Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders”, (1995), American Psychiatric Association<br />

Pub, Inc<br />

b) <strong>Abilities</strong><br />

b1. IQ AND “G” FACTOR<br />

“Ability to reason, solve problems, comprehend abstract associations, learn from experience <strong>and</strong> think<br />

abstractly.”<br />

One dominant factor “g” (“general factor”) refers to the first factor extracted from a factor analysis of<br />

cognitive tasks, which many researchers consider to represent general (vs. specific) intelligence.”It<br />

represents individuals’ abilities to perceive relationships <strong>and</strong> to derive conclusions from them. It is the<br />

basic ability that underlies the performance of different intellectual tasks”<br />

IQ specifically refers to one’s intelligence relative to one’s age group (especially for children)<br />

Main authors: Arthur Jensen;; Nathan Brody<br />

Measures:<br />

WISC: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children<br />

- Wechsler, D. (1974). Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised (WISC-R). New York: The<br />

Psychological Corporation.<br />

WAIS<br />

Raven’s Progressive Matrices<br />

ASVAB<br />

Literature:<br />

- Neisser U., Boodoo G., Bouchard T., Boykin W., Brody N., Ceci S., Halpern D., Loehlin J., Perloff R.,<br />

Sternberg R., Urbina S., (1996): “Intelligence: Knowns <strong>and</strong> Unknowns” American Psychologist 51(2),<br />

77-101<br />

- Gottfredson L., (1997) “Why “g” matters: the complexity of everyday life”, Intelligence.<br />

- Brody, N., (1992). Intelligence. Boston: Academic Press<br />

b2. SPECIFIC MENTAL ABILITIES<br />

“<strong>Abilities</strong> as measured by tests of an individual in areas of spatial visualization, perceptual need,<br />

number facility, verbal comprehension, word fluency, memory, inductive reasoning <strong>and</strong> so forth”<br />

An umbrella category for lower-level mental abilities, including math, verbal, <strong>and</strong> spatial abilities, as<br />

well as even more specific mental capacities. Measured by subtest scores on IQ tests<br />

- Lubinski D. (2004), “Introduction to the special section on cognitive abilities: 100 years after<br />

- Spearman's (1904) "‘General intelligence,’ objectively determined <strong>and</strong> measured." J <strong>Personality</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

Social Psychology 86, 96–111<br />

b3. CREATIVITY<br />

Ability to generate novel ideas <strong>and</strong> behaviors that solve problems.<br />

Measures:<br />

One measure for creativity is Gough 1979 “Creative <strong>Personality</strong> Scale”:<br />

- Gough, H. G. (1979). “A creative personality scale for the Adjective Check List”. Journal of <strong>Personality</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> Social Psychology, 37,1398-1405. Link to the scale:<br />

http://www.indiana.edu/~bobweb/Bob/Gough_Scale.doc<br />

Literature:<br />

- Eysenck, H.J. (1993): Creativity <strong>and</strong> <strong>Personality</strong>: Suggestions for a Theory, Psychological Inquiry,<br />

- Eysenck, H.J. (1994), “The measurement of creativity. In Dimensions of Creativity, M.A. Boden.<br />

- Cziksentmihalyi, M. (1996) “Creativity, Flow <strong>and</strong> the Psychology of Discovery <strong>and</strong> Invention”,<br />

London: Harper Collins<br />

12

- Simonton, D.(1984) , “Genius, Creativity <strong>and</strong> Leadership: Historiometric inquiries”, Harvard U Press.<br />

- Simonton, D. (1997) “Genius <strong>and</strong> Creativity: selected papers” Ablex Ed.<br />

b4. EXECUTIVE FUNCTION<br />

“Higher level cognitive processes that organize <strong>and</strong> order behavior, including logic <strong>and</strong> reasoning,<br />

abstract thinking, problem solving, planning <strong>and</strong> carrying out <strong>and</strong> terminating goal directed behavior”<br />

Broad set of higher-level cognitive capacities attributed to the prefrontal cortex, often involving the<br />

coordination <strong>and</strong> management of lower-level processes” (APA Dictionary)<br />

Executive functions are unrelated to “g”, but determine more basic abilities that can vary considerably<br />

among the population <strong>and</strong> that can be important in the process of acquiring cognitive skills: for<br />

example, Kim, Whyte, Vaccaro et al. show how executive functions may relate to attention, while<br />

Carpenter shows the relationship with working memory.<br />

Executive functions are usually measured by neuropsychology tasks (e.g., go/no-go, Stroop, Continuous<br />

Performance Task)<br />

Literature:<br />

- Miller E, Cohen J. (2001) "An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function". Annual Review of<br />

Neuroscience 24, 167-202<br />

- Miller, E.K. (2000) The prefrontal cortex <strong>and</strong> cognitive control. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 1:59-65<br />

- Miller Lab, with links to publications: http://www.millerlab.org<br />

- Blair C., Razza R.(2007), “Relating Effortful Control, Executive Function, <strong>and</strong> False Belief<br />

Underst<strong>and</strong>ing to Emerging Math <strong>and</strong> Literacy Ability in Kindergarten” Child Development 78 (2),<br />

647–663.<br />

- Carpenter P., (2000): “Working memory <strong>and</strong> executive function”, Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 10,<br />

195–19<br />

b6. EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE<br />

“Ability to process emotional information <strong>and</strong> use it in reasoning <strong>and</strong> other cognitive activities.<br />

According to Mayer <strong>and</strong> Slovey 1997 model It comprises four abilities: to perceive <strong>and</strong> appraise<br />

emotions accurately, to access <strong>and</strong> evoke emotions when they facilitate cognition, to comprehend<br />

emotional language <strong>and</strong> make use of emotional information, <strong>and</strong> to regulate one’s own <strong>and</strong> others’<br />

emotions to promote growth <strong>and</strong> well-being” Ability to perceive emotion, to integrate it in thought, to<br />

underst<strong>and</strong> it <strong>and</strong> to manage it (Mayer)” (APA Dictionary)<br />

Emotion is here considered as a feeling state that conveys information about relationships (Mayer), <strong>and</strong><br />

intelligence refers to the ability of reason validly about this information.<br />

Measures:<br />

The most reliable measure is considered to be the MSCEIT test, but it is not publicly available.<br />

The validity of self reported judgments is still highly debated<br />

Literature:<br />

- John Mayer website for emotional intelligence, with links to all relevant papers:<br />

http://www.unh.edu/emotional_intelligence/.<br />

See also:<br />

- Mayer J., Slovey P., (1997) ”What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey y D. Sluyter Eds., Emotional<br />

development <strong>and</strong> EI: Educational implications New York: Basic Books<br />

- Mayer, J. Caruso, D., Salovey, P. (1999).”Emotional intelligence meets traditional st<strong>and</strong>ards for an<br />

intelligence”. Intelligence, 27, 267-298.<br />

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D. R. (2000). Models of emotional intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg<br />

(Ed.). H<strong>and</strong>book of Intelligence (pp. 396-420). Cambridge, Engl<strong>and</strong>: Cambridge University Press.<br />

- Roberts R., Matthews G., Zeidner M., (2001), “Does Emotional Intelligence meet Traditional<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ards for Intelligence? Some New Data <strong>and</strong> Conclusions” Emotion, 1 (3), 196-231<br />

http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~pjm21/psychometrics/robertsetal2001.pdf<br />

- Roberts R., Matthews G., Zeidner M., (2004) “Emotional Intelligence: Science <strong>and</strong> Myth”, MIT Press,<br />

Cambridge, Massachussets.<br />

Goleman D.<br />

13

Motivation <strong>and</strong> IQ Summary<br />

Many of these studies used a within-subject design <strong>and</strong> measured the effect of motivation as the<br />

differential between performance with <strong>and</strong> without incentives. An intriguing possibility for<br />

measuring motivation not available at the time of these early studies is offered by Pailing &<br />

Segalowitz (2004). A particular error-related ERP (event-related potential) is a metric for the<br />

salience or importance of making an error. Subjects who are high in Conscientiousness or low in<br />

Neuroticism showed dampened changes in this particular ERP when incentives were given for<br />

improved performance.<br />

Table 3. Studies documenting an effect of motivation at the time of test administration <strong>and</strong> IQ<br />

score<br />

Study<br />

Edlund<br />

(1972)<br />

Ayllon &<br />

Kelly (1972)<br />

Sample 1<br />

Ayllon &<br />

Kelly (1972)<br />

Sample 2<br />

Ayllon &<br />

Kelly<br />

(1972)Sample<br />

3<br />

Sample <strong>and</strong><br />

Study Design<br />

Between<br />

subjects study.<br />

11 matched<br />

pairs of low<br />

SES children;<br />

children were<br />

about 1 SD<br />

below average<br />

in IQ at<br />

baseline<br />

Within subjects<br />

study. 12<br />

mentally<br />

retarded<br />

children (avg<br />

IQ 46.8)<br />

Within subjects<br />

study 34 urban<br />

fourth graders<br />

(avg IQ = 92.8)<br />

Within subjects<br />

study of 12<br />

matched pairs<br />

of mentally<br />

retarded<br />

children<br />

Experimental<br />

Group<br />

M&M c<strong>and</strong>ies<br />

given for each<br />

right answer<br />

Tokens given in<br />

experimental<br />

condition for<br />

right answers<br />

exchangeable for<br />

prizes<br />

Tokens given in<br />

experimental<br />

condition for<br />

right answers<br />

exchangeable for<br />

prizes<br />

Six weeks of<br />

token<br />

reinforcement for<br />

good academic<br />

performance<br />

Effect size of<br />

incentive (in<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard<br />

deviations)<br />

Experimental<br />

group scored 12<br />

points higher<br />

than control<br />

group during a<br />

second testing<br />

on an<br />

alternative form<br />

of the Stanford<br />

Binet (about .8<br />

SD)<br />

6.25 points out<br />

of a possible 51<br />

points on<br />

Metropolitan<br />

Readiness Test.<br />

t = 4.03<br />

t = 5.9<br />

Experimental<br />

group scored<br />

3.67 points out<br />

of possible 51<br />

points on a<br />

post-test given<br />

Summary<br />

“…a carefully chosen<br />

consequence, c<strong>and</strong>y,<br />

given contingent on<br />

each occurrence of<br />

correct responses to an<br />

IQ test, can result in a<br />

significantly higher IQ<br />

score.”(p. 319)<br />

“…test scores often<br />

reflect poor academic<br />

skills, but they may<br />

also reflect lack of<br />

motivation to do well<br />

in the criterion<br />

test…These results,<br />

obtained from both a<br />

population typically<br />

limited in skills <strong>and</strong><br />

ability as well as from<br />

a group of normal<br />

children (Experiment<br />

II), demonstrate that<br />

the use of<br />

reinforcement<br />

procedures applied to a<br />

behavior that is tacitly<br />

1

Clingman &<br />

Fowler<br />

(1976)<br />

Zigler &<br />

Butterfield<br />

(1968)<br />

Within subjects<br />

study of 72<br />

first- <strong>and</strong><br />

second-graders<br />

assigned<br />

r<strong>and</strong>omly to<br />

contingent<br />

reward,<br />

noncontingent<br />

reward, or no<br />

reward<br />

conditions.<br />

Within <strong>and</strong><br />

between<br />

subjects study<br />

of 40 low SES<br />

children who<br />

did or did not<br />

attend nursery<br />

school were<br />

tested at the<br />

beginning <strong>and</strong><br />

end of the year<br />

on Stanford-<br />

Binet<br />

Intelligence<br />

Test under<br />

either<br />

optimized or<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard cdtns.<br />

M&Ms given for<br />

right answers in<br />

contingent cdtn;<br />

M&Ms given<br />

regardless of<br />

correctness in<br />

noncontingent<br />

cdtn<br />

Motivation was<br />

optimized<br />

without giving<br />

test-relevant<br />

information.<br />

Gentle<br />

encouragement,<br />

easier items after<br />

items were<br />

missed, etc.<br />

under st<strong>and</strong>ard<br />

conditions<br />

higher than at<br />

baseline;<br />

control group<br />

dropped 2.75<br />

points. On a<br />

second post-test<br />

with incentives,<br />

exp <strong>and</strong> control<br />

groups<br />

increased 6.25<br />

<strong>and</strong> 7.17 points,<br />

respectively<br />

Only among<br />

low-IQ (

Breuning &<br />

Zella (1978)<br />

Holt & Robbs<br />

(1979)<br />

Within <strong>and</strong><br />

between<br />

subjects study<br />

of 485 special<br />

education high<br />

school students<br />

all took IQ<br />

tests, then were<br />

r<strong>and</strong>omly<br />

assigned to<br />

control or<br />

incentive<br />

groups to retake<br />

tests. Subjects<br />

were belowaverage<br />

in IQ.<br />

Between <strong>and</strong><br />

within subjects<br />

study of 80<br />

delinquent boys<br />

r<strong>and</strong>omly<br />

assigned to 3<br />

experimental<br />

groups <strong>and</strong> 1<br />

control group.<br />

Each exp group<br />

received a<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>and</strong><br />

modified<br />

administration<br />

of the WISCverbal<br />

section.<br />

Incentives such<br />

as record albums,<br />

radios (

Larson (1994) Between<br />

subjects study<br />

of 109 San<br />

Diego State<br />

University<br />

psychology<br />

students<br />

Duckworth<br />

(in<br />

preparation)<br />

Within subjects<br />

study of 61<br />

urban lowachieving<br />

high<br />

school students<br />

tested with a<br />

groupadministered<br />

Otis-Lennon IQ<br />

test during their<br />

freshman year,<br />

then again 2<br />

years later with<br />

a one-on-one<br />

(WASI) test<br />

Up to $20 for<br />

improvement<br />

over baseline<br />

performance on<br />

cognitive speed<br />

tests<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard<br />

directions for<br />

encouraging<br />

effort were<br />

followed for the<br />

WASI brief test.<br />

Performance was<br />

expected to be<br />

higher because of<br />

the one-on-one<br />

environment.<br />

“While both<br />

groups<br />

improved with<br />

practice, the<br />

incentive group<br />

improved<br />

slightly more.”<br />

need to<br />

calculate effect<br />

size, but it was<br />

not large<br />

Performance on<br />

the WASI as<br />

juniors was<br />

about 16 points<br />

higher than on<br />

the groupadministered<br />

test as<br />

freshmen.<br />

Notably, on the<br />

WASI, this<br />

population<br />

looks almost<br />

“average” in<br />

IQ, whereas by<br />

Otis-Lennon<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards they<br />

are low IQ. t<br />

(60) = 10.67, p<br />

< .001<br />

2 reasons why<br />

incentive did not<br />

produce dramatic<br />

increase: 1) few or no<br />

unmotivated subjects<br />

among college<br />

volunteers, 2)<br />

information processing<br />

tasks are too simple for<br />

‘trying harder’ to<br />

matter<br />

The increase in IQ<br />

scores could be<br />

attributed to any<br />

combination of the<br />

following 1) an<br />

increase in “g” due to<br />

schooling at an<br />

intensive charter<br />

school, 2) an increase<br />

in knowledge or<br />

crystallized<br />

intelligence, 3) an<br />

increase in motivation<br />

due to the change in IQ<br />

test format, <strong>and</strong>/or 4)<br />

an increase in<br />

motivation due to<br />

experience at high<br />

performing school<br />