ITAC Part-One - IMS Alliance

ITAC Part-One - IMS Alliance

ITAC Part-One - IMS Alliance

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

FIRE SERVICE LEADERSHIP >>><br />

By MARK EMERY<br />

Integrated Tactical<br />

Accountability<br />

“Engine 54, Where Are You?”<br />

<strong>Part</strong> 1 – Introducing a Freelance-Prevention System That Works<br />

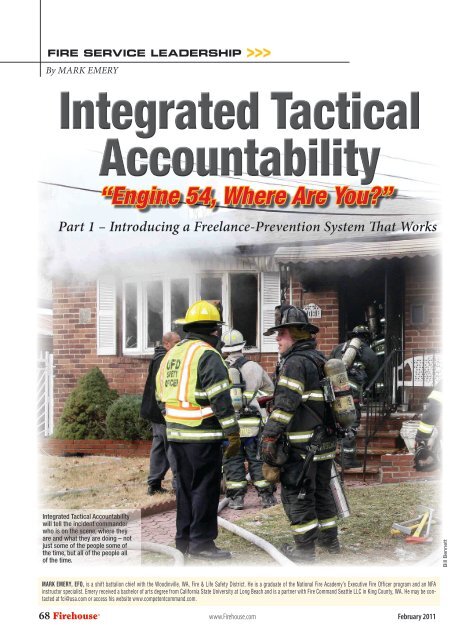

Integrated Tactical Accountability<br />

will tell the incident commander<br />

who is on the scene, where they<br />

are and what they are doing – not<br />

just some of the people some of<br />

the time, but all of the people all<br />

of the time.<br />

Bill Bennett<br />

MARK EMERY, EFO, is a shift battalion chief with the Woodinville, WA, Fire & Life Safety District. He is a graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer program and an NFA<br />

instructor specialist. Emery received a bachelor of arts degree from California State University at Long Beach and is a partner with Fire Command Seattle LLC in King County, WA. He may be contacted<br />

at fci@usa.com or access his website www.competentcommand.com.<br />

68 Firehouse ® www.Firehouse.com February 2011

FIRE SERVICE LEADERSHIP<br />

Let’s get right to the point: If your implementation of the National Incident Management System (N<strong>IMS</strong>) Incident<br />

Command System (ICS) does not help you achieve and maintain tactical accountability, your implementation<br />

“system” is flawed and incomplete.<br />

You may remember the TV sitcom<br />

“Car 54, Where Are You?” which aired<br />

from 1961 to 1963 and later in reruns.<br />

The story line centered on the comical<br />

exploits of NYPD officers Gunther Toody<br />

and Francis Muldoon and their assigned<br />

cruiser, Car 54. Nobody in the fictitious<br />

53rd Precinct ever seemed to know where<br />

Toody and Muldoon were or what they<br />

were doing. The lack of Car 54 accountability<br />

made for some good laughs.<br />

The contemporary fire service has<br />

had a variety of personnel accountability<br />

systems in place for many years. Each of<br />

these systems can tell you who is at an incident;<br />

few accountability systems can tell<br />

you where each firefighter is at any given<br />

moment. Integrated Tactical Accountability<br />

will tell you who is there, where they<br />

are and what they are doing – not just<br />

some of the people some of the time, but<br />

all of the people all of the time. Integrated<br />

Tactical Accountability implementation<br />

means that freelancing can be prevented<br />

and thus should no longer be tolerated.<br />

Nobody will have to ask, “Engine 54,<br />

where are you?”<br />

Putting It to Work<br />

Tactical accountability can be<br />

achieved without batteries, without software<br />

and without expensive gee-whiz<br />

gadgets, and it will work at 3 o’clock in<br />

the morning. Achieving and maintaining<br />

tactical accountability is quick and easy<br />

and dovetails perfectly with the tenets of<br />

N<strong>IMS</strong> ICS and NFPA 1561. In fact, the<br />

Integrated Tactical Accountability system<br />

is the only implementation system in<br />

North America that offers how to meet<br />

or exceed all of the performance requirements<br />

identified by NFPA 1561, Standard<br />

on Emergency Services Incident Management<br />

System (2008 edition).<br />

To declare that your fire department<br />

has adopted and uses N<strong>IMS</strong> to manage an<br />

incident is not entirely true. N<strong>IMS</strong> may<br />

provide a familiar ICS framework for<br />

managing an incident (what’s old is new<br />

again), but N<strong>IMS</strong> fails to provide implementation<br />

guidance. Example: While it’s<br />

nice to know that a division is defined as<br />

geographic and a group is defined as functional,<br />

exactly how are you supposed to<br />

“supervise” a division or group during a<br />

multi-alarm fire? Shouldn’t a division be<br />

doing something functional within its<br />

geographic area of responsibility? Likewise,<br />

shouldn’t a group be executing its<br />

function someplace geographic? If they<br />

are both functional and geographic,<br />

what’s the true difference? (We will explore<br />

this question in a future article.)<br />

How, and in what form, do group<br />

supervisors receive and supervise their<br />

pieces of the overall incident action plan?<br />

How do division supervisors achieve and<br />

maintain tactical accountability? When<br />

the incident commander or a branch director<br />

asks for a status report, what do<br />

the division or group supervisors report?<br />

These questions probe well beyond basic<br />

geographic and functional distinctions.<br />

N<strong>IMS</strong> won’t help implement the ICS<br />

any more than the NFPA 1901 committee<br />

will submit a bid to build your next fire<br />

engine. N<strong>IMS</strong> was designed for what attorney<br />

and risk-management guru Gordon<br />

Graham refers to as “discretionary<br />

time” incidents. Discretionary means you<br />

have time to schedule a planning meeting<br />

for the next operational period. You don’t<br />

The Challenge<br />

The purpose of this three-part series is to help you eliminate freelancing by achieving and maintaining tactical accountability.<br />

PART ONE WILL:<br />

1. Establish why tactical accountability is important.<br />

2. Identify National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards that “require” that you achieve and maintain<br />

tactical accountability.<br />

3. Introduce important distinctions between personnel accountability and tactical accountability.<br />

4. Identify who is responsible for personnel accountability.<br />

5. Identify who is responsible for tactical accountability.<br />

PART TWO WILL:<br />

1. Describe how to quickly achieve tactical accountability (using familiar strategic tools).<br />

2. Describe how to maintain tactical accountability throughout the course of an incident.<br />

3. Illustrate how to establish a “thread” that strategically connects the command post with a firefighter operating a<br />

nozzle within the hazard area.<br />

PART THREE WILL:<br />

1. Introduce the three levels of fireground freelancing.<br />

2. Describe how to eliminate geographic freelancing.<br />

3. Describe how to eliminate functional freelancing.<br />

4. Clarify the real difference between a division and a group.<br />

5. Introduce strategic tools for controlling the ebb and flow of incident resources.<br />

February 2011 www.Firehouse.com Firehouse ® 69

FIRE SERVICE LEADERSHIP >>><br />

have the luxury of discretionary time<br />

when you are the first on-scene fire officer<br />

at a 3-o’clock-in-the-morning, multifamily<br />

building fire. The operational period<br />

is in your face.<br />

Nobody is going to fill out ICS 201<br />

and 203 forms in the front yard at a house<br />

fire, schedule a meeting and circulate<br />

copies of the plan to arriving companies.<br />

(Doing so would be trying to hammer<br />

a discretionary square peg into a nondiscretionary<br />

round hole.) ICS planning<br />

forms are designed for long-term incidents<br />

that offer discretionary time. Integrated<br />

Tactical Accountability provides<br />

a structured and systematic process for<br />

the implementation of N<strong>IMS</strong> ICS and<br />

NFPA 1561 during in-your-face, nondiscretionary<br />

time incidents – the kind of<br />

incidents that you respond to every day.<br />

Standards and Mandates<br />

Standards and mandates (N<strong>IMS</strong> is<br />

a federal mandate) provide guidance on<br />

what we should do, but they do not hint<br />

at how we should comply. Compliance<br />

and implementation is up to the “authority<br />

having jurisdiction” (AHJ). To address<br />

the spirit and intent of a particular standard<br />

or mandate is up to your organization<br />

or region. Consider the following<br />

citations from the 2008 edition of NFPA<br />

1561, Standard on Emergency Services<br />

Incident Management System:<br />

4.5.2 The system shall maintain accountability<br />

for the location and status<br />

condition of each organizational element<br />

at the scene of the incident.<br />

5.3.10 The incident commander shall<br />

maintain an awareness of the location and<br />

function of all companies or units at the<br />

scene of the incident.<br />

5.8.9.1 All supervisory personnel shall<br />

maintain a constant awareness of the position<br />

and function of all responders assigned<br />

to operate under their supervision.<br />

5.8.9.2 This awareness shall serve as<br />

the basic means of accountability that<br />

shall be required for operational safety.<br />

Note the words I emphasized: location…condition…function…position…basic.<br />

What these NFPA citations require as a<br />

“basic means of accountability” is that the<br />

incident commander and division/group<br />

supervisors shall maintain an awareness<br />

of the location/position and function of all<br />

companies, units and responders (personnel).<br />

Also notice that this basic means of<br />

accountability shall be required for operational<br />

safety. NFPA 1561 ventures well beyond<br />

mere personnel tracking. However,<br />

as mentioned previously, NFPA does not<br />

provide a hint at how to make sure this<br />

happens. The term I coined for maintaining<br />

this location and function awareness<br />

is “tactical accountability.” The structured<br />

and systematic process which assures<br />

seamless compliance is called Integrated<br />

Tactical Accountability.<br />

“Accountability” Defined<br />

There is a significant difference between<br />

personnel accountability and tactical<br />

accountability. In general, “accountability”<br />

is defined as a process for tracking<br />

personnel during an incident. According<br />

to NFPA 1561, personnel accountability<br />

is a system that “readily identifies both<br />

the location and function of all members<br />

operating at an incident scene.” (There<br />

are those pesky words again: location and<br />

function.) “Location” means more than<br />

knowing that there are eight companies<br />

on the fireground and that there are a<br />

70 Firehouse ® www.Firehouse.com February 2011

FIRE SERVICE LEADERSHIP<br />

bunch of firefighters somewhere in the<br />

building; location means you know from<br />

what side each team entered the building<br />

and on what floor each team is working.<br />

Tactical accountability means that you<br />

also know what each team is doing and<br />

why. Again, if freelancing is tolerated, it is<br />

impossible to achieve and maintain tactical<br />

accountability.<br />

To ensure that the tenets of NFPA 1561<br />

– and N<strong>IMS</strong> ICS – are addressed, two levels<br />

of accountability are needed: personnel<br />

and tactical. The only way this can be<br />

achieved and maintained is by aggressive<br />

span-of-control management. More than<br />

anything else, the ICS is a span-of-control,<br />

resource-management system. Consider<br />

the following NFPA 1561 citations:<br />

5.1.6 The command structure for each<br />

incident shall maintain an effective supervisory<br />

span of control at each level of the<br />

organization.<br />

A.5.1.6 A span of control of responders<br />

between three and seven is considered<br />

desirable most cases.<br />

5.3.12 The incident commander shall<br />

initiate an accountability and inventory<br />

worksheet at the beginning of operations<br />

and shall maintain that system throughout<br />

operations.<br />

Note the conflict within these citations.<br />

For example, a span of control of three to<br />

seven is considered ideal, yet the incident<br />

commander is supposed to initiate – and<br />

maintain – an accountability and inventory<br />

worksheet throughout the incident. This<br />

is silly; imagine an incident commander<br />

fiddling with this worksheet throughout<br />

a multi-alarm incident. How can the incident<br />

commander maintain this inventory<br />

worksheet of all resources and maintain the<br />

ideal span of control at the command post?<br />

Not only does this violate fundamental ICS<br />

span of control, it doesn’t work. This is one<br />

reason why many fire departments choose<br />

to dump resource tracking responsibility on<br />

somebody else, this person is often called<br />

an “accountability officer.” Here’s a hint:<br />

The presence of an “accountability officer”<br />

is a reliable indicator that, first, the fire department<br />

has not integrated accountability<br />

into the Incident Command System, and,<br />

second, it does not know how to achieve<br />

and maintain tactical accountability (or, in<br />

many cases, is not aware that it should).<br />

The good news is that there has always<br />

been an ICS position with unlimited<br />

span of control and whose responsibility<br />

it is to track resources: the staging area<br />

manager. It’s no surprise that NFPA 1561<br />

advises that resources should check in<br />

with the staging area manager. Considering<br />

that advice, guess which ICS position<br />

Indicate 139 on Reader Service Card<br />

fire departments should assign to assist<br />

the incident commander with resource<br />

tracking? The bad news is that resource<br />

tracking is not tactical accountability.<br />

Staging provides non-hazard-area<br />

personnel accountability; the staging area<br />

manager can quickly tell you where Engine<br />

54 was sent (not where it is) and what<br />

February 2011 www.Firehouse.com Firehouse ® 71

FIRE SERVICE LEADERSHIP