Furnishing the Santa Fe Style - El Palacio Magazine

Furnishing the Santa Fe Style - El Palacio Magazine

Furnishing the Santa Fe Style - El Palacio Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

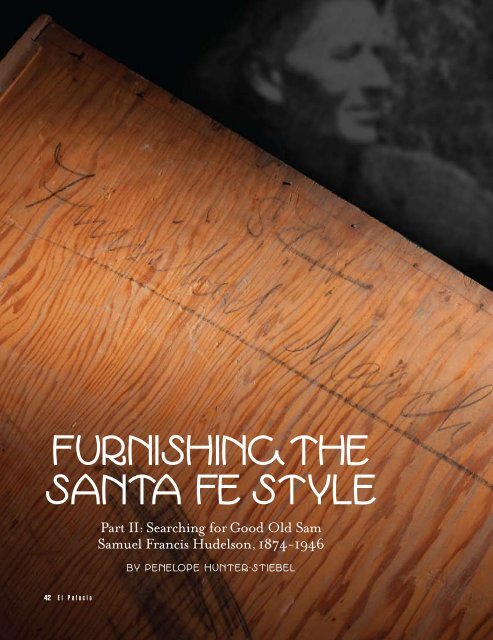

<strong>Furnishing</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong> <strong>Style</strong><br />

Part II: Searching for Good Old Sam<br />

Samuel Francis Hudelson, 1874-1946<br />

By Penelope Hunter-Stiebel<br />

42 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

Much of <strong>the</strong> furniture created for <strong>the</strong> New<br />

Mexico Museum of Art over <strong>the</strong> years since<br />

its opening in 1917 still exists in galleries<br />

and storage areas. Beyond Jesse Nusbaum’s readily identifiable<br />

contributions based on local Hispanic tradition<br />

lay a mystery. In a group of significant works an accomplished<br />

furniture maker had continued Nusbaum’s<br />

vocabulary while introducing elements from various<br />

Native American cultures. Who might be <strong>the</strong> author of<br />

this evidence of a developing triculturalism in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Santa</strong><br />

<strong>Fe</strong> style? And when were <strong>the</strong>se pieces made?<br />

Above: Desk carved with Indian motifs that provided <strong>the</strong> key for identifying<br />

<strong>the</strong> furniture of Sam Hudelson. The file drawer is carved with <strong>the</strong> initials<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Museum of New Mexico. Photograph by Blair Clark. All furniture<br />

made for <strong>the</strong> Museum of Art pictured here and throughout is shown courtesy<br />

of <strong>the</strong> New Mexico Museum of Art. Left: Pencil notation under <strong>the</strong><br />

center drawer of <strong>the</strong> desk with <strong>the</strong> initials of Samuel Francis Hudelson and<br />

dating his completion of <strong>the</strong> assignment to March 10, 1934, with emphatic<br />

flourish and underline. Photograph by Blair Clark.

SAM HUDELSON<br />

Firm in <strong>the</strong> belief that all <strong>the</strong> contents of <strong>the</strong> museum<br />

should be documented, Registrar Michelle Gallagher Roberts<br />

assigned her colleague Dan Goodman (now curator of collections<br />

at <strong>El</strong> Rancho de las Golondrinas) to work with me, and<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r we photographed, measured, and recorded every<br />

piece we could find. Most bore inventory numbers assigned<br />

in 1990, but no fur<strong>the</strong>r study had been undertaken to determine<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir author or date.<br />

Moving what appeared to be a battered radiator cover with<br />

elaborate carved Indian-style decoration out from under a<br />

window recess in a corner of a gallery, we found it to be a<br />

desk with <strong>the</strong> initials MNM carved on <strong>the</strong> front of <strong>the</strong> deep file<br />

drawer, clearly indicating official use for <strong>the</strong> Museum of New<br />

Mexico. But it was <strong>the</strong> shallow center drawer that provided<br />

<strong>the</strong> Eureka moment: when we removed <strong>the</strong> drawer we discovered<br />

scrawled in pencil underneath “SFH/ Finished March<br />

10-34.” We now had a lynchpin!<br />

Over <strong>the</strong> months when Dan could fit periodic furniture<br />

forays into his full schedule I was researching in libraries and<br />

archives where I had picked up on <strong>the</strong> name Sam Huddleson,<br />

Huddelson, or Hudelson, variously spelled. He had been<br />

officially added to <strong>the</strong> Museum of New Mexico staff in 1920<br />

as superintendent, with responsibility for <strong>the</strong> Palace of <strong>the</strong><br />

Governors and <strong>the</strong> Art Gallery (as <strong>the</strong> New Mexico Museum<br />

of Art was originally called) buildings, <strong>the</strong>n jointly administered<br />

with <strong>the</strong> School of American Research (SAR, now School<br />

of Advanced Research) under <strong>the</strong> founding director Edgar L.<br />

Hewett. “Superintendent” was <strong>the</strong> same title held by Jesse<br />

Nusbaum before his departure from <strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong> in December<br />

1917. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, Nusbaum in his memoirs credited Hudelson<br />

as one of <strong>the</strong> “good men” he had helping with <strong>the</strong> elaborate<br />

architectural woodwork he designed for <strong>the</strong> art museum. 1<br />

Finding S. F. H.<br />

What singled Hudelson out to me was <strong>the</strong> artist Will Shuster’s<br />

passing reference in a 1940 interview as he described <strong>the</strong><br />

scene in <strong>the</strong> art museum basement: “There’s Sam Huddleson<br />

[sic] presiding over a carpentry shop where Joe Bakos and<br />

Fremont <strong>El</strong>lis and several o<strong>the</strong>r artists are busy making frames<br />

and crating paintings . . . good old Sam ready to lend a helping<br />

hand or a bit of advice.” 2<br />

I couldn’t even be sure that “good old Sam” was <strong>the</strong> SFH<br />

written under <strong>the</strong> desk drawer as I could find no mention of<br />

a middle name—at least until I opened a manila envelope<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Fray Angélico Chávez History Library, crammed with<br />

Sam Hudelson posing with an unidentified “Indian Friend” in <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 50 (7),<br />

July 1943. Hudelson taught “industrial arts” for <strong>the</strong> Indian Service on several<br />

reservations before coming to <strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong> in 1912 to work with Jesse Nusbaum on<br />

<strong>the</strong> renovation of <strong>the</strong> Palace of <strong>the</strong> Governors. He held <strong>the</strong> post of superintendent<br />

for <strong>the</strong> Museum of New Mexico from 1920 until 1941.<br />

yellowed newspaper clippings. I carefully removed each crumbling,<br />

irrelevant bit of trivia published in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong> New<br />

Mexican mentioning <strong>the</strong> Museum of New Mexico until out<br />

came a one-paragraph obituary published on June 7, 1946, for<br />

“Hudelson, Samuel Francis,” stating he had been custodian of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Museum of New Mexico. At last <strong>the</strong> correct spelling and<br />

his middle name!<br />

The information that he had retired eight years earlier<br />

proved incorrect, but it sent me to back issues of <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> to<br />

see if <strong>the</strong> fact was mentioned. An appreciation of his service<br />

in <strong>the</strong> July 1943 issue revealed that he had actually retired in<br />

1941. In a brief biography, Assistant Editor Hulda R. Hobbs<br />

wrote that this son of a Texas rancher had come to <strong>Santa</strong><br />

44 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

SAM HUDELSON<br />

Hudelson’s photograph (ca. 1925–30) of his workshop in <strong>the</strong> basement of <strong>the</strong> New Mexico Museum of Art showing <strong>the</strong><br />

armchairs and table made for <strong>the</strong> Women’s Board Room in <strong>the</strong> foreground. The premises were frequently visited by artists and<br />

admirers, and, on his retirement, Hudelson was credited with “inaugurating <strong>the</strong> local renaissance of hand-made and handdecorated<br />

furniture.” Courtesy Palace of <strong>the</strong> Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 091790.<br />

<strong>Fe</strong> in 1912 when he worked on Jesse Nusbaum’s project of<br />

remodeling <strong>the</strong> Palace of <strong>the</strong> Governors, doing cabinetwork<br />

and continuing improvements, as well as <strong>the</strong> ornamental<br />

woodwork for <strong>the</strong> new Art Gallery. Hobbs credited Hudelson<br />

“with inaugurating <strong>the</strong> local renaissance of hand-made and<br />

hand-decorated furniture.” Now I knew that I was on <strong>the</strong><br />

right track!<br />

Hobbs’s claim about <strong>the</strong> significance of Hudelson’s contributions<br />

to furniture design is all <strong>the</strong> more amazing considering<br />

that Hudelson’s primary responsibility was maintenance,<br />

repair, and additions to <strong>the</strong> Museum of New Mexico campus<br />

(both <strong>the</strong> Palace of <strong>the</strong> Governors and <strong>the</strong> Art Museum). He<br />

also did field work every year with SAR working at Gran<br />

Quivira and Quarai, Jemez, Puyé, Chaco, Pecos, and Acoma.<br />

Hobbs quoted an official statement from Hewett (notoriously<br />

loath to credit his staff) saying, with uncharacteristic enthusiasm,<br />

“What this capable workman (artist as well as master<br />

mechanic) accomplished assisted by a few unskilled laborers,<br />

was beyond praise…. His methods have influenced <strong>the</strong> work<br />

of about all of us who have had to do with <strong>the</strong> preservation of<br />

ruins during this generation.”<br />

Furniture for Private Clients<br />

Hudelson himself was not a man of words, or at least not of<br />

written words. The only records that he made relating to <strong>the</strong><br />

Museum of Art that I could find were his photographs, now<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Photo Archives of <strong>the</strong> Palace of <strong>the</strong> Governors. A key<br />

image had been published by Lonn Taylor and Dessa Bokides<br />

in <strong>the</strong>ir invaluable book, New Mexican Furniture, 1600–1940. 3<br />

It showed furniture in <strong>the</strong> Art Museum basement with two<br />

of <strong>the</strong> armchairs for <strong>the</strong> Women’s Board Room in front of <strong>the</strong><br />

room’s long table, which was up on saw horses. No trace has<br />

been found of <strong>the</strong> foreground bench or <strong>the</strong> second table in <strong>the</strong><br />

background. Could <strong>the</strong>se have been made for a private client?<br />

Hewett was notoriously stingy when it came to paying his<br />

staff, who worked for both <strong>the</strong> museum and SAR. Most were<br />

considered “part time” employees and expected to supplement<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir salaries with outside work.<br />

It was just such extracurricular work that forced Hudelson<br />

to put words in writing. I was led to <strong>the</strong> SAR library archive<br />

by Kathy Fiero, who is writing a biography of Nusbaum<br />

and shared with me an unpublished manuscript by Lonn<br />

Taylor on <strong>the</strong> construction and furnishing of <strong>the</strong> Martha and<br />

<strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 45

SAM HUDELSON<br />

<strong>El</strong>izabeth White house now occupied by SAR. 4 Although <strong>the</strong>y<br />

engaged as <strong>the</strong>ir architect William Penhallow Henderson, who<br />

developed a furnituremaking business, <strong>the</strong> White sisters wrote<br />

to Nusbaum that <strong>the</strong>y wanted furniture like that <strong>the</strong>y had seen<br />

in his home at Mesa Verde. Since he was <strong>the</strong>n fully occupied<br />

with his duties as superintendent of Mesa Verde National<br />

Park, Nusbaum said from <strong>the</strong> start that he could design <strong>the</strong><br />

pieces but that <strong>the</strong>y would have to be made by Hudelson in<br />

his shop in <strong>the</strong> museum basement. An agreement was struck<br />

for twenty-two pieces, and correspondence between <strong>the</strong><br />

Whites, Nusbaum, and Hudelson covering 1923–25 in <strong>the</strong><br />

SAR archives reveals a dynamic collaboration with sketches<br />

and measured drawings and commentary. 5 I found a number<br />

of <strong>the</strong> pieces documented in photographs by Hudelson among<br />

<strong>the</strong> images he donated to <strong>the</strong> museum, now in <strong>the</strong> Palace<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Governors Photo Archives. The project stirred great<br />

interest, and visits to Hudelson’s basement workshop were so<br />

frequent that Nusbaum wrote him, “Who comes <strong>the</strong> most to<br />

offer suggestions and criticisms of ‘Grand Rapids.’ Nordfelt<br />

[<strong>the</strong> painter. J. O Nordfelt (1878-1955), I suppose]. Guess he<br />

will be imitating lot of things later in his house if I do not miss<br />

my guess.” There was also correspondence with <strong>the</strong> museum’s<br />

assistant director, Paul Walter, about <strong>the</strong> possibility of an exhibition<br />

which never came about.<br />

The White furniture was just one of Hudelson’s furniture<br />

commissions: in a letter to Nusbaum dated March 10, 1924,<br />

Hudelson wrote, “contracted 2 large chairs—4 benches—one<br />

thin table $390.00 for a lady here. Will begin as soon as [I]<br />

finish yours.” Clearly <strong>the</strong>se pieces were of Hudelson’s own<br />

design and may represent an extended production that is yet<br />

to be identified.<br />

The clue to identifying Hudelson’s independent work lies<br />

in <strong>the</strong> carved ornament. In a letter dated March 7, 1924,<br />

Nusbaum complained to Martha White “he [Hudelson] was<br />

too ambitious in carving and everywhere he could lay a dollar<br />

down on it, he had to carve it, That ruins it for me…” 6<br />

Examining <strong>the</strong> Museum of Art furniture, we may not agree<br />

with his assessment of a developing style born of Hudelson’s<br />

personal experience.<br />

From <strong>the</strong> 1943 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> article I learned that at age nineteen<br />

Hudelson was hired as a teacher of “industrial arts” for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Indian service. Starting in Oklahoma, where his parents<br />

had homesteaded, he was transferred to San Carlos Apache<br />

school in Rice, Arizona; <strong>the</strong>n to Fort Dermitt, Nevada, on <strong>the</strong><br />

Paiute Reservation; and finally to Tohatchi, New Mexico, on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Navajo Reservation, before coming to <strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong> in 1911.<br />

Putting this toge<strong>the</strong>r with what was happening at <strong>the</strong> museum<br />

from <strong>the</strong> time of Nusbaum’s departure, <strong>the</strong> rationale behind<br />

<strong>the</strong> museum furnishings came into focus.<br />

This varied experience of Native American communities<br />

combined well with <strong>the</strong> museum’s increased focus on contemporary<br />

Indian arts. What Hewett called “The <strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong><br />

Program” started with promoting a revival of pottery at San<br />

Ildefonso and moved on to <strong>the</strong> presentation of Pueblo painters<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Art Gallery. Two breakthrough exhibitions of students<br />

of <strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong> Indian school in 1919 brought a “new” art form<br />

to <strong>the</strong> attention of <strong>the</strong> Anglo community. In 1924 <strong>the</strong> Art<br />

Gallery’s eleventh annual survey exhibition presented as usual<br />

<strong>the</strong> latest paintings by members of <strong>the</strong> Taos and <strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong> artists<br />

colonies, but also dedicated <strong>the</strong> upstairs gallery to paintings<br />

by Indian artists. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> report in <strong>the</strong> September 24<br />

<strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> stated that in <strong>the</strong> arts and crafts section where work<br />

was presumably by non-Indians, “<strong>the</strong> application of Indian<br />

designs as applied to <strong>the</strong> decoration of china and was of high<br />

merit and attracted much attention.” The 1934 frescoes by<br />

Will Shuster in <strong>the</strong> museum patio illustrating Pueblo Indian<br />

scenes left a lasting reminder of <strong>the</strong> institution’s involvement.<br />

Hudelson’s Distinctive Designs<br />

Kenneth Chapman stands out as a pioneer in <strong>the</strong> appreciation<br />

of Indian design. As Hewett’s first employee at <strong>the</strong> museum<br />

and SAR he devoted whatever hours could be spared from<br />

administrative duties to begin a life-long study of Pueblo<br />

ceramics, analyzing <strong>the</strong> decorations and working <strong>the</strong>m up in<br />

hundreds of sheets of watercolor studies. Under <strong>the</strong> auspices<br />

of <strong>the</strong> WPA he even conducted classes where artists emulated<br />

This ca. 1923 photograph by <strong>the</strong> Cross Studio shows a Hudelson bench in situ.<br />

Courtesy Palace of <strong>the</strong> Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 022975.<br />

46 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

Benches carved with Pueblo and Navajo motifs Hudelson made to cover radiators and provide<br />

supplemental seating in <strong>the</strong> Women’s Board Room by <strong>the</strong> early 1920s. Photographs by Blair Clark.<br />

<strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 47

Left: A small bookcase whose carvings, including a swastika, traditional in<br />

Navajo weaving, allow <strong>the</strong> piece to be dated before <strong>the</strong> motif was associated <strong>the</strong><br />

threat of Hitler’s Nazi party. Photograph by Blair Clark.<br />

his process. He created a lens through which Anglo admirers<br />

perceived this form of ceramic art, and Indian motifs entered<br />

<strong>the</strong> vocabulary of contemporary decoration.<br />

Hudelson’s initial use of Indian-style ornament may have<br />

been in two benches supplied to provide additional seating<br />

and cover <strong>the</strong> radiators in <strong>the</strong> Women’s Board Room, as shown<br />

in photographs from <strong>the</strong> early 1920s. On one he carved friezes<br />

and stepped motifs in common use in <strong>the</strong> pueblos, and on <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r he carved openings in <strong>the</strong> low back that recall motifs of<br />

Navajo rugs.<br />

Early in our exploration Dan Goodman and I stumbled<br />

across a small bookcase in <strong>the</strong> museum storage. The carvings<br />

of <strong>the</strong> sides are almost a lexicon of Southwest Indian design.<br />

The inclusion of <strong>the</strong> design of <strong>the</strong> swastika that had long figured<br />

in Navajo weaving told us that <strong>the</strong> piece had to predate<br />

American awareness of <strong>the</strong> threat from Hitler, who had appropriated<br />

<strong>the</strong> age-old symbol for his Nazi party.<br />

A double bench still in use in <strong>the</strong> galleries recalls <strong>the</strong> commercial<br />

“Mission style” of <strong>the</strong> benches purchased by Hewett<br />

for <strong>the</strong> gallery opening, but <strong>the</strong> outlines are softened and <strong>the</strong><br />

sides with cut-out slats below incised Indian-inspired motifs<br />

convey a distinct Southwest character.<br />

Were <strong>the</strong> Indian motifs Hudelson carved on <strong>the</strong> art museum<br />

furniture copied from Chapman’s designs? After examining a<br />

number of Chapman’s works I felt <strong>the</strong> carvings were of a very<br />

different character. I was vastly relieved when Dody Fugate,<br />

assistant curator for archaeological research collections at <strong>the</strong><br />

Laboratory of Anthropology, confirmed my observation, saving<br />

me hours and hours of poring over still more Chapmania.<br />

Most of Hudelson’s carvings are free improvisations adapting<br />

Indian design elements, from Mimbres pots to Navajo weavings,<br />

drawn from his personal experience. There were two<br />

outstanding exceptions, however. One was <strong>the</strong> front panel on<br />

a small reception desk. On seeing my snapshot, Dody cried<br />

out, “That’s a Hopi pot!” as indeed <strong>the</strong> carved bird design<br />

resembles that painted on a Hopi pot that she led me to on <strong>the</strong><br />

shelves of <strong>the</strong> Museum of Indian Arts & Culture storeroom.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> second case I already knew <strong>the</strong> source, since Dody<br />

had published it in her recent <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> article coauthored<br />

with Pete Pino. I recognized <strong>the</strong> sun symbol carved on <strong>the</strong> side<br />

of <strong>the</strong> chest of shallow drawers in <strong>the</strong> museum basement and<br />

also on <strong>the</strong> side of a desk that has has been traditionally called<br />

48 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

SAM HUDELSON<br />

Above: A double bench still used in <strong>the</strong> museum galleries. Its softened<br />

“Mission” style is given Southwestern character by <strong>the</strong> cut-out slats and<br />

Indian-inspired engraving at each end. Photograph by Blair Clark.<br />

Right: Small reception desk with <strong>the</strong> front panel carved with a motif<br />

similar to those on Hopi pottery. Photograph by Blair Clark.<br />

<strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 49

SAM HUDELSON<br />

The “Director’s desk” with <strong>the</strong> initials of <strong>the</strong> Museum of New Mexico on <strong>the</strong><br />

file drawer. It can be dated to around 1931–32 and still serves as <strong>the</strong> work station<br />

of <strong>the</strong> current director of <strong>the</strong> Art Museum, Mary Kershaw, who graciously allowed it<br />

to be cleared for photography. The side panel of “<strong>the</strong> Director’s desk” exactly<br />

replicates <strong>the</strong> motif on an important Zia pot. Adapted by <strong>the</strong> addition of a fourth<br />

ray and <strong>the</strong> elimination of <strong>the</strong> sun’s facial features, <strong>the</strong> motif was <strong>the</strong> winning entry<br />

in <strong>the</strong> 1920 competition for a New Mexico state flag. Hudelson would have been<br />

familiar with <strong>the</strong> original pot that was donated by <strong>the</strong> painter Andrew Dasburg to<br />

<strong>the</strong> School of American Research in 1931 and housed in <strong>the</strong> museum buildings in<br />

Hudelson’s charge. Photograph by Blair Clark.<br />

and remains in use as “<strong>the</strong> Director’s desk.” Both of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

carvings differ in character from <strong>the</strong> symbol as adopted for<br />

<strong>the</strong> New Mexico state flag, with only three, not four rays. The<br />

sun on <strong>the</strong> Director’s desk has a face, with eyes and mouth.<br />

I had not realized until <strong>the</strong> Fugate/Pino article that this was<br />

precisely <strong>the</strong> decoration on <strong>the</strong> Zia pot donated to SAR in<br />

1931 by <strong>the</strong> painter Andrew Dasburg and recently repatriated.<br />

Hudelson would certainly have known <strong>the</strong> celebrated<br />

acquisition. He would have been well acquainted with ceramics<br />

in <strong>the</strong> collection, as he would have relocated <strong>the</strong>ir storage<br />

on <strong>the</strong> repeated occasions when Hewett reassigned spaces in<br />

<strong>the</strong> museum buildings.<br />

Inset: The Zia pot that inspired<br />

Hudelson’s carvings and <strong>the</strong> New<br />

Mexico flag. Courtesy Peter Pino<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Pueblo of Zia.<br />

Several pieces in <strong>the</strong> art museum that have elements suggesting<br />

Hudelson’s work give evidence of being subsequently<br />

heavily reworked and/or transformed by succeeding generations<br />

of carpenters. The huge table currently occupying <strong>the</strong><br />

location of <strong>the</strong> original table made for <strong>the</strong> Women’s Board<br />

Room, which is now in <strong>the</strong> museum lobby, appears to be<br />

a composite. The Indian motifs carved on <strong>the</strong> apron are in<br />

Hudelson’s style but <strong>the</strong>y include one carved on <strong>the</strong> inside<br />

of <strong>the</strong> apron, indicating <strong>the</strong> wood was a trial piece or salvaged<br />

from ano<strong>the</strong>r use. As in <strong>the</strong> 1917 original, <strong>the</strong> massive<br />

Solomonic spiral column legs are hand-hewn, but <strong>the</strong> overall<br />

proportions are awkward, being exaggerated in length with a<br />

single central stretcher and a shallow apron. The structure is<br />

held toge<strong>the</strong>r with metal plates bracing <strong>the</strong> corners, unthinkable<br />

for a craftsman of Hudelson’s caliber.<br />

50 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

A chest with shallow drawers,<br />

probably intended for works on paper.<br />

Here Hudelson enhanced <strong>the</strong> decorative<br />

vocabulary Nusbaum based in regional<br />

Hispanic tradition for <strong>the</strong> Women’s Board<br />

Room with Pueblo motifs, including <strong>the</strong> Zia<br />

sun symbol on <strong>the</strong> sides. Hudelson’s<br />

furniture for <strong>the</strong> museum illustrated<br />

<strong>the</strong> institution’s active promotion of <strong>the</strong><br />

aes<strong>the</strong>tic value of Native American art and<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r amplified <strong>the</strong> developing “<strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong><br />

<strong>Style</strong>.” Photograph by Blair Clark.<br />

Not long ago I learned that <strong>the</strong> chest with shallow drawers<br />

carved with stepped Indian motifs and sides carved with <strong>the</strong><br />

Zia symbol had narrowly escaped plans for cutting it up for<br />

adaptive use. Some twenty years ago <strong>the</strong> museum director<br />

hesitated and consulted Robin Farwell Gavin, <strong>the</strong>n curator<br />

of Spanish Colonial art at <strong>the</strong> Museum of International<br />

Folk Art. She advised him that though it was not a Spanish<br />

Colonial antique, it was a piece of real merit that might be<br />

part of <strong>the</strong> early furnishings of <strong>the</strong> museum and should be<br />

preserved. It has carving on all sides indicating that it was<br />

made to be free-standing in a place where it could be seen in<br />

<strong>the</strong> round. Its shallow drawers were probably made for <strong>the</strong><br />

storage of works on paper, perhaps <strong>the</strong> paintings by Indian<br />

artists that were not only exhibited but also sold by <strong>the</strong><br />

museum. It would make sense to associate <strong>the</strong> decoration of<br />

such a functional showpiece with its contents.<br />

An Artist Too<br />

Recently I discovered an unexpected aspect of Good Old Sam’s<br />

unsung creativity by following a lead in Kenneth Chapman’s<br />

papers at <strong>the</strong> School of American Research. 7 He listed<br />

Hudelson as a participant in a two-week exhibition staged<br />

in a single alcove at <strong>the</strong> Art Gallery at <strong>the</strong> height of <strong>the</strong> controversy<br />

over “Modernist” art in 1924. The museum seemed<br />

to have no record of <strong>the</strong> exhibition, but searching through<br />

microfilm of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong> New Mexican I discovered a review<br />

titled “Astigmatic Expressionists” (<strong>Fe</strong>bruary 16, 1924). While<br />

most works were given tongue-in-cheek criticism, Hudelson’s<br />

contribution received straight-forward comment. His silverpoint<br />

drawing of <strong>the</strong> Devil was commended as “remarkable<br />

for its intimacy and detail.” Fur<strong>the</strong>r it was stated, “His woman<br />

drawn with a single line also reveals this carpenter’s familiarity<br />

with his subject.”<br />

There is so much more to be learned about Sam Hudelson,<br />

but identifying some of <strong>the</strong> furniture he made for <strong>the</strong> New<br />

Mexico Museum of Art is a first step that sheds light on this<br />

historic phase of <strong>the</strong> Museum of New Mexico as it took <strong>the</strong><br />

lead in embracing and validating Native American creativity.<br />

Hudelson’s furniture incorporated Indian design into <strong>the</strong><br />

evolving “<strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong> <strong>Style</strong>.” n<br />

NOTES<br />

1. Rosemary Nusbaum, Tierra Dulce, Reminiscences from <strong>the</strong><br />

Jesse Nusbaum Papers. (<strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong>: Sunstone Press, 1980), 63.<br />

2. Quoted by Janet Chapman and Karen Barr, Kenneth Milton Chapman,<br />

(Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008), 137).<br />

3. <strong>Santa</strong> <strong>Fe</strong>: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1987, 216.<br />

4. Thanks to Lonn Taylor, who has generously allowed me to cite his research.<br />

5. School for Advanced Research, SAR AC 28.<br />

6. From <strong>the</strong> papers of Nusbaum’s daughter, Rosemary Talley,<br />

quoted by Lonn Taylor.<br />

7. School for Advanced Research, Kenneth Chapman Papers (AC02:157.1).<br />

<strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 51