wma 7-2.indd - World Medical Association

wma 7-2.indd - World Medical Association

wma 7-2.indd - World Medical Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

WMA news<br />

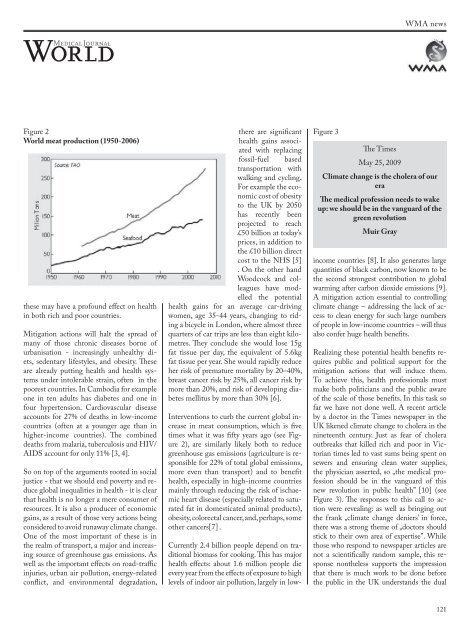

Figure 2<br />

<strong>World</strong> meat production (1950-2006)<br />

these may have a profound effect on health<br />

in both rich and poor countries.<br />

Mitigation actions will halt the spread of<br />

many of those chronic diseases borne of<br />

urbanisation - increasingly unhealthy diets,<br />

sedentary lifestyles, and obesity. These<br />

are already putting health and health systems<br />

under intolerable strain, often in the<br />

poorest countries. In Cambodia for example<br />

one in ten adults has diabetes and one in<br />

four hypertension. Cardiovascular disease<br />

accounts for 27% of deaths in low-income<br />

countries (often at a younger age than in<br />

higher-income countries). The combined<br />

deaths from malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/<br />

AIDS account for only 11% [3, 4].<br />

So on top of the arguments rooted in social<br />

justice - that we should end poverty and reduce<br />

global inequalities in health - it is clear<br />

that health is no longer a mere consumer of<br />

resources. It is also a producer of economic<br />

gains, as a result of those very actions being<br />

considered to avoid runaway climate change.<br />

One of the most important of these is in<br />

the realm of transport, a major and increasing<br />

source of greenhouse gas emissions. As<br />

well as the important effects on road-traffic<br />

injuries, urban air pollution, energy-related<br />

conflict, and environmental degradation,<br />

there are significant<br />

health gains associated<br />

with replacing<br />

fossil-fuel based<br />

transportation with<br />

walking and cycling.<br />

For example the economic<br />

cost of obesity<br />

to the UK by 2050<br />

has recently been<br />

projected to reach<br />

£50 billion at today’s<br />

prices, in addition to<br />

the £10 billion direct<br />

cost to the NHS [5]<br />

. On the other hand<br />

Woodcock and colleagues<br />

have modelled<br />

the potential<br />

health gains for an average car-driving<br />

women, age 35-44 years, changing to riding<br />

a bicycle in London, where almost three<br />

quarters of car trips are less than eight kilometres.<br />

They conclude she would lose 15g<br />

fat tissue per day, the equivalent of 5.6kg<br />

fat tissue per year. She would rapidly reduce<br />

her risk of premature mortality by 20–40%,<br />

breast cancer risk by 25%, all cancer risk by<br />

more than 20%, and risk of developing diabetes<br />

mellitus by more than 30% [6].<br />

Interventions to curb the current global increase<br />

in meat consumption, which is five<br />

times what it was fifty years ago (see Figure<br />

2), are similarly likely both to reduce<br />

greenhouse gas emissions (agriculture is responsible<br />

for 22% of total global emissions,<br />

more even than transport) and to benefit<br />

health, especially in high-income countries<br />

mainly through reducing the risk of ischaemic<br />

heart disease (especially related to saturated<br />

fat in domesticated animal products),<br />

obesity, colorectal cancer, and, perhaps, some<br />

other cancers[7] .<br />

Figure 3<br />

The Times<br />

May 25, 2009<br />

Climate change is the cholera of our<br />

era<br />

The medical profession needs to wake<br />

up: we should be in the vanguard of the<br />

green revolution<br />

Muir Gray<br />

Currently 2.4 billion people depend on traditional<br />

biomass for cooking. This has major<br />

health effects: about 1.6 million people die<br />

every year from the effects of exposure to high<br />

levels of indoor air pollution, largely in lowincome<br />

countries [8]. It also generates large<br />

quantities of black carbon, now known to be<br />

the second strongest contribution to global<br />

warming after carbon dioxide emissions [9].<br />

A mitigation action essential to controlling<br />

climate change – addressing the lack of access<br />

to clean energy for such large numbers<br />

of people in low-income countries – will thus<br />

also confer huge health benefits.<br />

Realizing these potential health benefits requires<br />

public and political support for the<br />

mitigation actions that will induce them.<br />

To achieve this, health professionals must<br />

make both politicians and the public aware<br />

of the scale of those benefits. In this task so<br />

far we have not done well. A recent article<br />

by a doctor in the Times newspaper in the<br />

UK likened climate change to cholera in the<br />

nineteenth century. Just as fear of cholera<br />

outbreaks that killed rich and poor in Victorian<br />

times led to vast sums being spent on<br />

sewers and ensuring clean water supplies,<br />

the physician asserted, so „the medical profession<br />

should be in the vanguard of this<br />

new revolution in public health” [10] (see<br />

Figure 3). The responses to this call to action<br />

were revealing: as well as bringing out<br />

the frank „climate change deniers’ in force,<br />

there was a strong theme of „doctors should<br />

stick to their own area of expertise”. While<br />

those who respond to newspaper articles are<br />

not a scientifically random sample, this response<br />

nontheless supports the impression<br />

that there is much work to be done before<br />

the public in the UK understands the dual<br />

121