Read Animal Aid's scientific Briefing on the Bristol experiments

Read Animal Aid's scientific Briefing on the Bristol experiments

Read Animal Aid's scientific Briefing on the Bristol experiments

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Genetically modified mouse<br />

<strong>experiments</strong> at <strong>Bristol</strong> University –<br />

cruel and without medical benefit<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Briefing</str<strong>on</strong>g> sheet<br />

www.animalaid.org.uk • tel: 01732 364546<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Animal</str<strong>on</strong>g> Aid, during <strong>the</strong> course of researching its<br />

Science Corrupted report into <strong>the</strong> suffering endured<br />

by genetically modified (GM) mice, uncovered a l<strong>on</strong>grunning<br />

series of deeply unpleasant animal <strong>experiments</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>ducted at <strong>Bristol</strong> University. We have rigorously<br />

examined <strong>the</strong> justificati<strong>on</strong>s given for such work, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> details of exactly what <strong>the</strong> mice endured. We<br />

c<strong>on</strong>clude that <strong>the</strong> research, in comm<strong>on</strong> with a mass of<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r recent and c<strong>on</strong>temporary <strong>experiments</strong>, is both<br />

extremely cruel and without <str<strong>on</strong>g>scientific</str<strong>on</strong>g> merit.<br />

These c<strong>on</strong>tinuing <strong>experiments</strong> are investigating, in<br />

animals, <strong>the</strong> role of a protein-like substance called<br />

galanin in pain percepti<strong>on</strong>. Researchers have created<br />

and bred both knockout and transgenic mice 1 , with<br />

<strong>the</strong> inevitable mass killing and death from ‘side effects’<br />

that such processes entail. GM mice have <strong>the</strong>n been<br />

subjected to prol<strong>on</strong>ged pain <strong>experiments</strong>, which<br />

involve nerve damage surgery followed by protracted<br />

suffering in a range of invasive testing regimes.<br />

The first of <strong>the</strong> papers we cite was published in 1998,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> most recent in 2012. A c<strong>on</strong>tinuous flow of<br />

public and charity m<strong>on</strong>ey has kept <strong>the</strong> programme<br />

going for <strong>the</strong> last 15 years. Despite milli<strong>on</strong>s of pounds<br />

in funding, it has yet to produce any new treatments<br />

for patients.<br />

Mice are complex, sensitive animals<br />

Mice used in <strong>experiments</strong> are no less complex or<br />

vulnerable than <strong>the</strong>ir wild-living counterparts. The<br />

laboratory envir<strong>on</strong>ment is completely alien to <strong>the</strong>m, and<br />

already fraught with potential stressors even before<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are subjected to <strong>the</strong> procedures detailed below.<br />

Mice are a prey species, which means that <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

highly motivated to stay close to safe cover. They<br />

also find routine human c<strong>on</strong>tact very stressful unless<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are properly habituated, and are especially upset<br />

by being caught or handled. They have an inherent<br />

tendency to hide signs of pain or distress, and can<br />

become unwell and deteriorate quickly, with often<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly subtle signs of suffering, until illness is severe.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Animal</str<strong>on</strong>g>s in laboratories are often selected <strong>on</strong> grounds<br />

of c<strong>on</strong>venience and traditi<strong>on</strong>, ra<strong>the</strong>r than any predictive<br />

value for human ailments. Mice, for example, breed<br />

prolifically and are relatively cheap to buy and maintain.<br />

Dozens of mice have <strong>the</strong>ir nerves<br />

crushed, tied or severed<br />

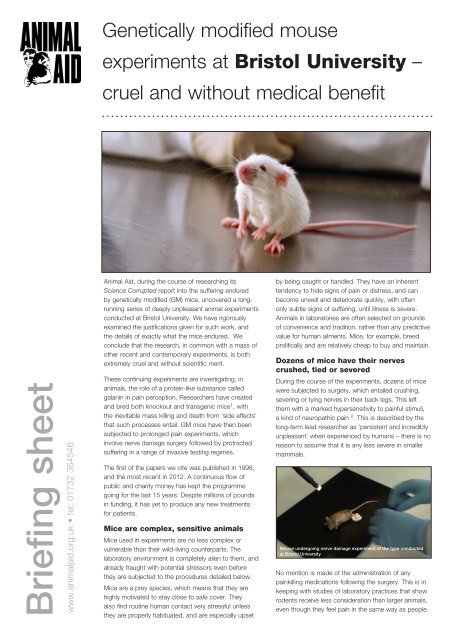

During <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong> <strong>experiments</strong>, dozens of mice<br />

were subjected to surgery, which entailed crushing,<br />

severing or tying nerves in <strong>the</strong>ir back legs. This left<br />

<strong>the</strong>m with a marked hypersensitivity to painful stimuli,<br />

a kind of neuropathic pain 2 . This is described by <strong>the</strong><br />

l<strong>on</strong>g-term lead researcher as ‘persistent and incredibly<br />

unpleasant’ when experienced by humans – <strong>the</strong>re is no<br />

reas<strong>on</strong> to assume that it is any less severe in smaller<br />

mammals.<br />

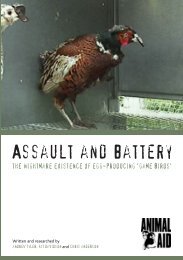

Mouse undergoing nerve damage experiment of <strong>the</strong> type c<strong>on</strong>ducted<br />

at <strong>Bristol</strong> University<br />

No menti<strong>on</strong> is made of <strong>the</strong> administrati<strong>on</strong> of any<br />

painkilling medicati<strong>on</strong>s following <strong>the</strong> surgery. This is in<br />

keeping with studies of laboratory practices that show<br />

rodents receive less c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong> than larger animals,<br />

even though <strong>the</strong>y feel pain in <strong>the</strong> same way as people.

Paws poked with wires, heated up and<br />

injected with corrosives<br />

After enduring nerve damage surgery, mice had <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

hypersensitive back paws poked repeatedly with fine<br />

wires, <strong>the</strong>y were heated with <strong>the</strong>rmal beams or <strong>the</strong>y<br />

were injected with formalin (a highly irritant corrosive).<br />

This inflicti<strong>on</strong> of pain was performed <strong>on</strong> repeated<br />

occasi<strong>on</strong>s, from shortly after surgery until <strong>the</strong> end of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>experiments</strong> two weeks later.<br />

In o<strong>the</strong>r procedures, mice with nerve damage had <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

paws dipped in food colouring, and were <strong>the</strong>n made<br />

to walk <strong>on</strong> white paper, to establish how crippled <strong>the</strong>y<br />

were. O<strong>the</strong>rs had <strong>the</strong>ir skin injected with substances<br />

that caused violent itching, or had <strong>the</strong> active ingredient<br />

in chilli pepper injected into <strong>the</strong>ir cheeks.<br />

Distressing and lethal ‘side effects’ of<br />

genetic modificati<strong>on</strong><br />

Many animal victims of genetic manipulati<strong>on</strong> suffer<br />

unforeseen and unpredictable ‘side effects’, in additi<strong>on</strong><br />

to <strong>the</strong> intended suffering from <strong>the</strong>ir designer diseases.<br />

The <strong>Bristol</strong> researchers report how <strong>the</strong>y generated<br />

knockout mice with <strong>the</strong> gene for galanin producti<strong>on</strong><br />

disabled, through gene targeting in embry<strong>on</strong>ic stem<br />

cells 3 . The team reported that ‘mutant females fail<br />

to lactate and pups die of starvati<strong>on</strong>/dehydrati<strong>on</strong><br />

unless fostered <strong>on</strong>to wild-type mo<strong>the</strong>rs. This apparent<br />

failure of lactati<strong>on</strong> was absolute during <strong>the</strong> first two<br />

pregnancies.’ Clearly, many pups were callously<br />

allowed to die, as ‘in subsequent pregnancies, 80 per<br />

cent of pups died but <strong>on</strong> some occasi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong>e or two<br />

survived to <strong>the</strong> weaning period’.<br />

Mass destructi<strong>on</strong> of living creatures<br />

The researchers created and bred <strong>the</strong>ir own lines<br />

of genetically engineered mice for subsequent<br />

experimentati<strong>on</strong>. These procedures are notable for<br />

<strong>the</strong> waste of lives and sheer scale of animal killing<br />

required. The initial creati<strong>on</strong> stages, for example, entail<br />

<strong>the</strong> deaths of hundreds of animals to produce <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

<strong>on</strong>e ‘founder’. Mice who are judged to be ‘excess’<br />

or ‘failures’ are generally gassed or have <strong>the</strong>ir necks<br />

broken.<br />

C<strong>on</strong>tradictory findings even between<br />

animal studies<br />

On several occasi<strong>on</strong>s, <strong>the</strong> researchers reported<br />

findings that c<strong>on</strong>tradicted previous animal <strong>experiments</strong><br />

in different species, findings in o<strong>the</strong>r GM mice and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r mouse pain ‘models’, as well as <strong>the</strong> ‘existing<br />

pharmacological data’.<br />

They stated in <strong>on</strong>e case that ‘<strong>the</strong> most obvious<br />

explanati<strong>on</strong>s for <strong>the</strong> apparent discordance in<br />

nociceptive (pain) behaviours between <strong>the</strong>se two<br />

different GalR2-MUT (mutant) lines are that each<br />

study has used a different model of neuropathic<br />

pain, and <strong>the</strong> animals have been generated <strong>on</strong><br />

differing genetic backgrounds’. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong><br />

results of <strong>the</strong> <strong>experiments</strong> are not even verifiable<br />

between different kinds of mice. The absurdity of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir extrapolati<strong>on</strong> to humans, <strong>the</strong>refore, is glaringly<br />

obvious. The researchers, however, proposed fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

pain <strong>experiments</strong> <strong>on</strong> more knockout mice to clarify <strong>the</strong><br />

problem.<br />

‘An eye fixed firmly <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> marketplace’<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Briefing</str<strong>on</strong>g> sheet<br />

www.animalaid.org.uk • tel: 01732 364546<br />

The <strong>Bristol</strong> papers do not specify how many ‘surplus’<br />

mice were killed prior to <strong>the</strong> creati<strong>on</strong> of a stable GM<br />

line. Minutes of a <strong>Bristol</strong> University Ethical Review<br />

Meeting from 2010, however, refer to an experimental<br />

series entitled: ‘The adaptive resp<strong>on</strong>se of <strong>the</strong> nervous<br />

system to injury’. This title is identical to that found <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Bristol</strong> University website of <strong>the</strong> lead researcher,<br />

and to a Home Office public summary that describes<br />

<strong>the</strong> experimental protocols. It is highly unlikely that<br />

<strong>the</strong> Ethical Review does not refer to <strong>the</strong> <strong>experiments</strong><br />

detailed in this <str<strong>on</strong>g>Briefing</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

The minutes, released under <strong>the</strong> Freedom of<br />

Informati<strong>on</strong> Act, show that ‘very high numbers of<br />

animals are needed for <strong>the</strong> maintenance of genetic<br />

lines due to several factors including <strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong><br />

research group and <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> use of multiple<br />

crosses means <strong>on</strong>ly 1 in 64 animals may be usable.<br />

However, <strong>the</strong>re was c<strong>on</strong>cern that <strong>the</strong> use of 18,000<br />

animals in <strong>the</strong> renewal applicati<strong>on</strong> was not justified in<br />

<strong>the</strong> text. It was noted that large numbers of animals<br />

were also quoted in <strong>the</strong> original applicati<strong>on</strong>.’ Despite<br />

<strong>the</strong>se c<strong>on</strong>cerns, <strong>the</strong> Ethical Review Body approved <strong>the</strong><br />

renewal of <strong>the</strong> project licence.<br />

As in many cases of university research, <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

clear links between <strong>the</strong> researcher’s publicly funded<br />

<strong>experiments</strong> and <strong>the</strong>ir potential for private profit.<br />

A c<strong>on</strong>tinuous flow of public and charity m<strong>on</strong>ey<br />

(including a £4.3 milli<strong>on</strong> grant in 2010 from <strong>the</strong><br />

Wellcome Trust) has sp<strong>on</strong>sored <strong>the</strong> programme for <strong>the</strong><br />

last 15 years. In 2007, its lead researcher was paid out<br />

of public funds (from <strong>the</strong> Medical Research Council) to<br />

spend six m<strong>on</strong>ths at GlaxoSmithKline learning about<br />

drug development – having founded his own ‘spinout’<br />

drug company from <strong>Bristol</strong> University some years<br />

earlier.<br />

In fact, <strong>the</strong> lead researcher is clearly keen to tap<br />

<strong>the</strong> ‘billi<strong>on</strong> dollar market’ for drugs for neuropathic<br />

pain. The <strong>Bristol</strong> University Annual Report from 2004<br />

describes his drug company ‘bounding forward with<br />

its eye fixed firmly <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> marketplace’, with its founder<br />

extolling <strong>the</strong> commercial potential of <strong>Bristol</strong>’s many<br />

research programmes.<br />

For patients in pain, <strong>the</strong> wait c<strong>on</strong>tinues<br />

An article in Nature Medicine (2010) highlights <strong>the</strong><br />

‘abysmal track record’ of animal pain <strong>experiments</strong><br />

- <strong>the</strong>y ‘have produced an explosi<strong>on</strong> of informati<strong>on</strong>

about pain, but this knowledge has failed to yield new<br />

painkillers for humans’. A 2010 meta-analysis of 174<br />

randomised c<strong>on</strong>trolled trials (RCTs) of neuropathic pain<br />

treatments found that <strong>the</strong> majority of patients saw no<br />

benefit, with a high number of early drop-outs because<br />

of adverse drug reacti<strong>on</strong>s. A L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong> researcher<br />

commented at that time: ‘The animal models of<br />

neuropathic pain just d<strong>on</strong>’t seem to be that efficient.’<br />

poor mimic of human disease. The damage induced in<br />

young, genetically identical and usually male animals is<br />

fundamentally different from <strong>the</strong> pain experienced by<br />

patients with chr<strong>on</strong>ic diseases, who are often elderly.<br />

The kind of neuropathic pain experienced by patients<br />

with diabetes, post-viral syndromes and cancer, for<br />

example, is not due to injury of <strong>the</strong>ir peripheral nerves<br />

such as that inflicted <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Bristol</strong> mice.<br />

The <strong>Bristol</strong> <strong>experiments</strong> are no excepti<strong>on</strong>. Despite<br />

inflicting c<strong>on</strong>siderable suffering <strong>on</strong> animals, <strong>the</strong>y have<br />

so far produced no c<strong>on</strong>crete benefits for patients.<br />

Galanin was discovered in 1978. It bel<strong>on</strong>gs to a group<br />

of substances known as neuropeptides, because of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir role in biological communicati<strong>on</strong>s between nerve<br />

cells. Galanin is found widely in mammalian central<br />

and peripheral nervous systems, and also in horm<strong>on</strong>e<br />

producing organs. The chemical is involved in several<br />

biological processes, including pain percepti<strong>on</strong>, eating<br />

and sleep regulati<strong>on</strong> and mood. However, despite<br />

decades of basic research (mainly but not exclusively<br />

using rodents), <strong>the</strong> roles of galanin in <strong>the</strong> human<br />

body remain far from clear. Molecules that both block<br />

and stimulate galanin receptors have been tested in<br />

‘animal models’ of pain, epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease,<br />

morphine addicti<strong>on</strong>, alcoholism, eating disorders,<br />

depressi<strong>on</strong> and anxiety. Many of <strong>the</strong>se <strong>experiments</strong><br />

involve manifestly cruel physical and psychological<br />

torments.<br />

The disc<strong>on</strong>nect between <strong>the</strong> preclinical animal studies<br />

and <strong>the</strong> subsequent human trials is enormous. A 2008<br />

article, authored by animal pain researchers, points out<br />

that ‘of <strong>the</strong> 123 interventi<strong>on</strong>s assessed in <strong>the</strong> 105 RCTs<br />

included in a recent clinical meta-analysis, 53% were<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ducted in patients with peripheral polyneuropathies<br />

and 21% were in post-herpetic neuralgia patients. In<br />

c<strong>on</strong>trast, <strong>on</strong>ly 9% of <strong>the</strong> RCTs studied patients with<br />

peripheral nerve injury.’<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r reas<strong>on</strong> for <strong>the</strong> systematic failure to help<br />

human patients is <strong>the</strong> measurement of largely irrelevant<br />

data. These <strong>experiments</strong> are measuring evoked<br />

hypersensitivity of a mouse paw after a peripheral nerve<br />

injury, via withdrawal from a painful stimulus. However,<br />

<strong>the</strong> predominant symptom suffered by patients with<br />

neuropathic pain (and <strong>the</strong>refore <strong>the</strong> primary measure<br />

of a treatment’s efficacy) is sp<strong>on</strong>taneous pain.<br />

Limb withdrawal in an injured animal is expected<br />

to somehow represent patients’ pain intensity and<br />

character, psychological status, sleep disturbance,<br />

physical functi<strong>on</strong> and overall quality of life.<br />

‘A measurable failure of replacement<br />

and reducti<strong>on</strong>’<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Briefing</str<strong>on</strong>g> sheet<br />

www.animalaid.org.uk • tel: 01732 364546<br />

Mouse in nerve damage experiment<br />

However, this c<strong>on</strong>tinued inflicti<strong>on</strong> of suffering has not<br />

resulted, to date, in even <strong>on</strong>e galanin-based drug<br />

being approved for use in any human disease. In<br />

fact, <strong>the</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>scientific</str<strong>on</strong>g> literature is littered with speculative<br />

declarati<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong>rapeutic breakthroughs that date<br />

back at least 25 years. The Home Office summary of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Bristol</strong> <strong>experiments</strong> makes clear that <strong>the</strong> primary<br />

purpose of <strong>the</strong> <strong>experiments</strong> is not patient care, but <strong>the</strong><br />

acquisti<strong>on</strong> of ‘new knowledge’, and that ‘<strong>the</strong> aim is<br />

to publish <strong>the</strong> findings in academic journals’. Human<br />

health is <strong>on</strong>ly a ‘sec<strong>on</strong>dary potential benefit…in so far<br />

as <strong>the</strong> results may at some later stage be of value in<br />

<strong>the</strong> development of new pharmaceutical products’.<br />

Pain research <strong>on</strong> mice does not<br />

translate to humans<br />

The <strong>Bristol</strong> <strong>experiments</strong> are basic research, involving<br />

<strong>the</strong> laboratory destructi<strong>on</strong> of animal physiology and<br />

anatomy in <strong>the</strong> hope of finding out something clinically<br />

relevant. It has been estimated that this kind of work<br />

has <strong>on</strong>ly a 0.004 per cent chance of leading to a new<br />

class of drug.<br />

The pain model used in <strong>the</strong>se <strong>experiments</strong> is a very<br />

‘Researchers c<strong>on</strong>ducting prol<strong>on</strong>ged pain research <strong>on</strong><br />

mice are paying little, if any, heed to 3Rs principles in<br />

<strong>the</strong> planning and executi<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong>ir research.’ This was<br />

<strong>on</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> damning c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s of a literature review<br />

published in January 2013. The study details how <strong>the</strong><br />

total amount of prol<strong>on</strong>ged pain research (defined as<br />

that which subjects mice to a source of pain for at least<br />

14 days), and <strong>the</strong> number of mice used, has increased<br />

dramatically in <strong>the</strong> past decade. The use of transgenic<br />

mice has also risen significantly.<br />

The authors discovered that nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> 3Rs c<strong>on</strong>cept,<br />

nor any of <strong>the</strong> 3Rs comp<strong>on</strong>ents - replace, reduce, or<br />

refine - were menti<strong>on</strong>ed in any of 55 randomly selected<br />

recent studies. This ‘suggests that prol<strong>on</strong>ged mouse<br />

pain researchers may be unaware of or indifferent to<br />

<strong>the</strong> 3Rs framework’, and that ‘adherence to guidelines<br />

and/or animal use committee requirements is not<br />

translating into significant progress from a reducti<strong>on</strong><br />

or replacement perspective’. This is hardly surprising,<br />

given <strong>the</strong> highly permissive and n<strong>on</strong>-critical attitude of<br />

most Ethical Reviews.<br />

Science Corrupted<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong>se failings, <strong>Bristol</strong> University currently<br />

remains committed to animal-based research, much<br />

of which involves GM mice. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Animal</str<strong>on</strong>g> Aid has produced<br />

a fully referenced <str<strong>on</strong>g>scientific</str<strong>on</strong>g> report, Science Corrupted,<br />

which reveals how, every year, milli<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

sensitive and vulnerable animals suffer a chain of<br />

misery. It begins with <strong>the</strong> invasive procedures needed<br />

to create new genetic lines, and <strong>the</strong>n c<strong>on</strong>tinues<br />

with <strong>the</strong> harmful effects of genetic alterati<strong>on</strong>, col<strong>on</strong>y

eeding, experimentati<strong>on</strong> and traumatic death. The<br />

scale of suffering involved is incomparably greater than<br />

any o<strong>the</strong>r area of animal experimentati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, using GM mice to mimic human disease<br />

is not delivering meaningful healthcare advances.<br />

This peculiar science c<strong>on</strong>tinues to lead to ineffective<br />

drugs, disastrous clinical trials, and <strong>the</strong> dashing of<br />

<strong>the</strong> elevated hopes of hundreds of thousands of<br />

patients and <strong>the</strong>ir carers. Science Corrupted details<br />

<strong>the</strong> serious misgivings of numerous researchers and<br />

commentators about <strong>the</strong> value and relevance of this<br />

work.<br />

Humane research and medical progress<br />

In c<strong>on</strong>trast to <strong>the</strong> asserti<strong>on</strong>s made to <strong>the</strong> Home Office<br />

by <strong>the</strong> researchers, <strong>the</strong>re are alternative approaches<br />

that can replace animal use in pain <strong>experiments</strong>.<br />

Studies <strong>on</strong> cultured human skin cells, minimally<br />

invasive microdialysis testing, and studies of human<br />

nerve tissue have all been used to investigate <strong>the</strong> role<br />

of galanin. Brain-imaging technologies, like functi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

MRI, are a powerful tool for investigating allodynia 4 in<br />

patients. As <strong>the</strong> 2013 study cited above points out: ‘In<br />

<strong>the</strong> area of pain research, ethical clinical studies with<br />

human patients have <strong>the</strong> advantage that humans can<br />

reliably report <strong>the</strong>ir experience of pain and pain relief.’<br />

Double helix - <strong>the</strong> structure of DNA<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Briefing</str<strong>on</strong>g> sheet<br />

www.animalaid.org.uk • tel: 01732 364546<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Animal</str<strong>on</strong>g> Aid, like <strong>the</strong> general public, is keen to see<br />

research undertaken that is both humane and has<br />

a good prospect of leading to genuine medical<br />

advancement. However, GM mouse <strong>experiments</strong> are<br />

a betrayal of patients desperate for genuine progress<br />

instead of endless false dawns. <strong>Bristol</strong> University must<br />

give a clear commitment that it will end all involvement<br />

in irrelevant and cruel animal <strong>experiments</strong>.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Read</str<strong>on</strong>g> Science Corrupted and view <str<strong>on</strong>g>Animal</str<strong>on</strong>g> Aid’s short<br />

film about GM mouse <strong>experiments</strong> at<br />

www.animalaid.org.uk/GMmice<br />

References available <strong>on</strong> request<br />

1 Transgenic animals have been altered to carry<br />

a foreign gene from ano<strong>the</strong>r organism within <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

natural genome. Knockout animals have certain genes<br />

prevented from working.<br />

2 Neuropathic pain is chr<strong>on</strong>ic pain resulting from<br />

damage to or dysfuncti<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> nervous system<br />

3 For a detailed explanati<strong>on</strong> of this technique, please<br />

see page 13 of <str<strong>on</strong>g>Animal</str<strong>on</strong>g> Aid’s Science Corrupted report<br />

4 Allodynia is pain produced by a stimulus that does<br />

not normally produce pain