Programme - FIFA/CIES International University Network

Programme - FIFA/CIES International University Network

Programme - FIFA/CIES International University Network

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

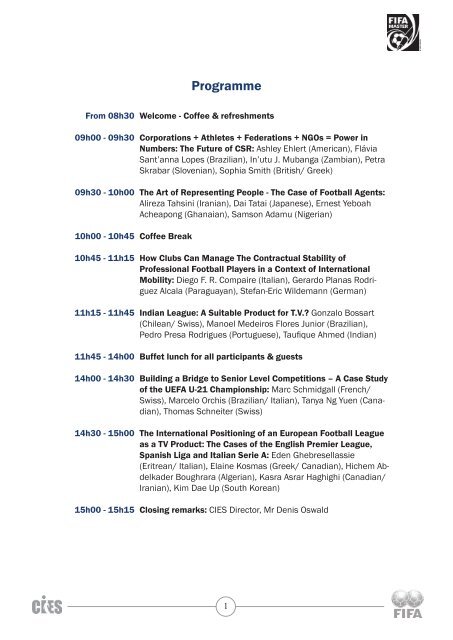

<strong>Programme</strong><br />

From 08h30<br />

09h00 - 09h30<br />

09h30 - 10h00<br />

10h00 - 10h45<br />

10h45 - 11h15<br />

11h15 - 11h45<br />

11h45 - 14h00<br />

14h00 - 14h30<br />

14h30 - 15h00<br />

15h00 - 15h15<br />

Welcome - Coffee & refreshments<br />

Corporations + Athletes + Federations + NGOs = Power in<br />

Numbers: The Future of CSR: Ashley Ehlert (American), Flávia<br />

Sant’anna Lopes (Brazilian), In’utu J. Mubanga (Zambian), Petra<br />

Skrabar (Slovenian), Sophia Smith (British/ Greek)<br />

The Art of Representing People - The Case of Football Agents:<br />

Alireza Tahsini (Iranian), Dai Tatai (Japanese), Ernest Yeboah<br />

Acheapong (Ghanaian), Samson Adamu (Nigerian)<br />

Coffee Break<br />

How Clubs Can Manage The Contractual Stability of<br />

Professional Football Players in a Context of <strong>International</strong><br />

Mobility: Diego F. R. Compaire (Italian), Gerardo Planas Rodriguez<br />

Alcala (Paraguayan), Stefan-Eric Wildemann (German)<br />

Indian League: A Suitable Product for T.V.? Gonzalo Bossart<br />

(Chilean/ Swiss), Manoel Medeiros Flores Junior (Brazilian),<br />

Pedro Presa Rodrigues (Portuguese), Taufique Ahmed (Indian)<br />

Buffet lunch for all participants & guests<br />

Building a Bridge to Senior Level Competitions – A Case Study<br />

of the UEFA U-21 Championship: Marc Schmidgall (French/<br />

Swiss), Marcelo Orchis (Brazilian/ Italian), Tanya Ng Yuen (Canadian),<br />

Thomas Schneiter (Swiss)<br />

The <strong>International</strong> Positioning of an European Football League<br />

as a TV Product: The Cases of the English Premier League,<br />

Spanish Liga and Italian Serie A: Eden Ghebresellassie<br />

(Eritrean/ Italian), Elaine Kosmas (Greek/ Canadian), Hichem Abdelkader<br />

Boughrara (Algerian), Kasra Asrar Haghighi (Canadian/<br />

Iranian), Kim Dae Up (South Korean)<br />

Closing remarks: <strong>CIES</strong> Director, Mr Denis Oswald<br />

1

Corporations + Athletes + Federations +<br />

NGO’s = Power in Numbers:<br />

The Future of CSR<br />

Ashley Ehlert (American)<br />

Flavia Sant’anna Lopes (Brazilian)<br />

In’utu J. Mubanga (Zambian)<br />

Petra Skrabar (Slovenian)<br />

Sophia Smith (British/Greek)<br />

This research project focuses on Corporate Social Responsibility in the sporting goods industry, determining<br />

key practices to aid not only sporting goods corporations in effective CSR strategies, but also aid federations,<br />

athletes, and NGO’s towards powerful CSR futures through strategic partnerships. Today, sport<br />

is more than just about a game. Sport holds a key that has the power to change and fix the problems in<br />

society. While this power is not evenly distributed through the sport family and while not all sport family<br />

members effectively utilize the power, each member has the ability to harness the inextricable intertwined<br />

power between them and sport towards a better future for society. The sporting goods industry represents<br />

one such sport family member that has the ability to use sport to benefit society in its CSR programs.<br />

However, until sporting goods corporations implement key practices for their CSR programs, specifically,<br />

utilizing the full power behind the sport family as a group, the true power within sport will be lost in wasted<br />

resources, wasted time, and wasted money.<br />

Research Hypotheses:<br />

• If industry standards of key practices are identified for the sporting goods industry utilizing a knowledge<br />

management system to engage in environmental CSR initiatives then the initiatives will become more powerful<br />

• If sporting goods corporations collaborate with members of the sports family who share the same environmental<br />

goals, then they will establish critical mass capable of producing a behavioral shift towards<br />

protecting the environment.<br />

Key Findings<br />

1. Why sporting goods corporations should engage in CSR. CSR is a concept that has existed since the<br />

Mesopotamia time when farmers were put to death if their negligence caused local citizens deaths. Cor-<br />

2

porations have historically and still today engaged in CSR for moral purposes – economic system should<br />

further the general social welfare, and economic purposes– CSR allows for watertight brand protection<br />

around key stakeholders. Thus, whether a sporting goods corporation engages in CSR to help the general<br />

society or to protect its brand, as social expectations of companies responsible nature increases, as product<br />

options increase, and as globalization allows both corporations to move to “pollution haven” countries<br />

and media to instantaneously draw a company’s mistake to the public’s attention, sporting goods corporations<br />

must recognize that success in the global market is dependent on an effective CSR program.<br />

2. Sporting goods corporations are taking a proactive stance. Today, sporting goods corporations are attempting<br />

to not only meet legal requirements but also attempting to take extra steps to actively contribute<br />

to positive changes in their communities through programs involving the environment, human rights and<br />

labor practices, organizational governance, fair business practices, community involvement, and consumer<br />

issues. Most large sporting good corporations (Adidas, Puma, Nike) are exceeding and driving public,<br />

legal, and market requirements for responsible companies, with most smaller brands, tailored brands, or<br />

geographically limited brands (Mizuno and Shimano) not engaging global CSR programs to the extent of<br />

the global reach of their individual products.<br />

3. Sporting goods corporations should go green in their CSR mission. Environmentally friendly corporations<br />

control the use of massive resources whereby changing their habits allows them to make a bigger difference<br />

on the environment than individuals. Sporting goods corporations hold an even greater power than<br />

general companies towards environmental CSR through the very nature of the products they sell. Sport and<br />

the environment have a natural partnership where the health and safety of athletes and the sports community<br />

depends on an intact environment. Sporting goods corporations need to accept their role in promoting<br />

sports that continually place a demand on natural resources and move towards harmonization with sports<br />

and the environment for a greener planet.<br />

4. Sporting goods corporation’s key practices towards effective CSR. While most sporting goods corporations<br />

utilize a variety of imperfect tools to facilitate their CSR practices, the top five sporting goods<br />

corporations utilized for this research uncovered that most sporting goods corporations CSR practices<br />

are unique and particular to the respective company particularly playing off the cultural views associated<br />

with the company’s country of incorporation and primary business countries. However, five key practices<br />

include: (a) transparency for all CSR activities; (b) open communication leading towards collective action;<br />

(c) monitoring and evaluating CSR initiatives; (d) leveraging the brand with a laser-sharp focus weaving<br />

the CSR mission into every dimension of the corporations; and (e) open innovation and collaboration with<br />

the entire sport family.<br />

3

5. The sporting goods industry will benefit by consolidating their key practices into a knowledge management<br />

system in order to share practices amongst them and thereby prevent reinventing the wheel – decreasing<br />

costs, increasing efficiency, and ensuring the success of the corporation’s CSR initiatives.<br />

6. Because the sporting goods industry is a member of the sports family, along with athletes and sporting<br />

bodies, it shares a common goal to protect the environment, as recognized by the Olympic Movement’s<br />

Agenda 21. Agenda 21 uses this common goal to bind the sports family together and shows how members<br />

can work together to establish a critical mass capable of affecting an overall change in society’s behavior<br />

towards the environment. While partnering to achieve environmental sustainability goals, corporations<br />

and other stakeholders receive benefits including financial incentives, cost sharing, increased efficiency,<br />

knowledge sharing, increased effectiveness through extended program reach, and promotion incentives.<br />

7. Sporting goods corporations must utilize a cross collaboration model to realize the true power of sport<br />

within their CSR programs. Sporting goods corporations should effectively collaborate with members of<br />

the sports family and traditional sectors to implement a 360 degree activation plan which incorporate all<br />

sectors working together to form an environmental sustainability movement. By establishing a cross-sector<br />

model where each member shares a common goal, sport’s critical mass will be more diverse with each<br />

member bringing a unique aspect. This diversity will create a partnership more powerful in its ability to<br />

tackle worldwide problems such as environmental degradation.<br />

8. Further, this cross-sector collaboration will benefit by including a facilitator role capable of instituting<br />

a knowledge management system, capable of communicating with all parties, and that can establish<br />

a uniform labeling system to communicate one clear message regarding the environmental progress each<br />

member has made through its actions.<br />

4

The Art of Representing People -<br />

The Case of Football Agents<br />

Alireza Tahsini (Iranian)<br />

Dai Tatai (Japanese)<br />

Ernest Yeboah Acheapong (Ghanaian)<br />

Samson Adamu (Nigerian)<br />

Objectives<br />

The project “The Art of Representing People – The Case of Football Agents” aims to draw a set of best<br />

practices for the current football agents industry. It looks into the world of football agents by analyzing the<br />

current situation regarding the regulations governing agents’ activities and the reality of how they actually<br />

perform their duties and responsibilities. Ever since globalisation swept the world of football, agents have<br />

been the centre of discussion when it comes to transfer of players. For example, managers in football clubs<br />

accuse them of causing inflation in football because they are constantly striving to increase the wages of<br />

players. One of the questions this paper would try to answer is that, are agents’ fulfilling their essence as<br />

long as they keep their clients (the players) happy and every other person frowns on them?<br />

To identify the likely best practises for football agents, the project carefully looks into the activities of other<br />

agents worldwide. The industries chosen to achieve this objective are modelling, Hollywood, Literature, and<br />

American sports (NBA, NHL, NFL, and MLB). We carefully looked into these industries to learn the techniques<br />

they have used in managing their talents and possibly try to adopt the applicable ones to football.<br />

Methods<br />

To achieve the aim of this project, we reviewed the history of agents and the contribution they have made<br />

to the development of football and assessed the current environment. We highlighted the major issues with<br />

the situation of football agents in the 21th century, and then looked at the unique practises in the other industries<br />

that are not present in football. We went further to identify certain practices that are applicable to<br />

the optimisation of the issues we pointed out in the players’ agent industry. The last step was to implement<br />

the best practices and give further suggestions on how they can be applied. To carry out this research, we<br />

used the following sources to gather qualitative and quantitative data:<br />

5

• Face to face and telephone interviews with the different industries experts who were extremely helpful.<br />

• Web surveys.<br />

• Books and online periodic journals.<br />

• Information on the sport magazines and online sport business articles.<br />

Findings<br />

One of the key findings in this project is that the regulating body of agents’ activities is actually doing a<br />

good job but the difficulty of regulating activities of agents comes from the international scope of football.<br />

As long as there are no common international laws and football is not exempted from the effect of globalisation,<br />

there would never be a perfect solution to regulating football agents’ activities and agents would<br />

always be relevant to football.<br />

Agents sometimes face criticism because of the activities they do not perform for the agents. What many of<br />

the critics do not consider is what might be written in the contract between the player and the agent. Agents’<br />

standard contractual obligation towards a player is to negotiate contracts for the player in the course of<br />

sign with a club or renewal of contracts.<br />

Recommendation<br />

Based on the findings and analysis, a number of recommendations have been made and few of these recommendations<br />

include:<br />

• Players association such as FIFPRO and relevant National Association player associations should have<br />

a more active role in monitoring the activities of agents.<br />

• Education of players on what to expect from agents with seminars and workshops, especially the younger<br />

players.<br />

• There should be an online database with vital information on agents to give players better options to shop<br />

their agents.<br />

• National Associations and players associations to strongly advice player to seek legal advice before signing<br />

a contract with an agent.<br />

• Agents should be remunerated on performance base.<br />

• National Associations and player associations should provide a list of recommended service providers for<br />

players seeking certain services in which his agent lack the necessary skill, such as career management.<br />

6

Conclusion<br />

Even though, football agents are considered to be one of the most controversial figures in the sport world,<br />

the need of a professional who can deal with the vast amount of money involved in football today is necessary.<br />

The agent is like an actor starring in a movie that is showing in the theatre, however, the audience is not<br />

the fan, club, or the governing body, but the player and the player alone. Therefore it is enough to give the<br />

agent credit or say he is doing a good job if he makes sure his client is happy.<br />

7

How Clubs Can Manage The Contractual<br />

Stability of Professional Football Players in<br />

a Context of <strong>International</strong> Mobility<br />

Diego F. R. Compaire (Italian)<br />

Gerardo Planas Rodriguez Alcala (Paraguayan)<br />

Stefan-Eric Wildemann (German)<br />

“Contractual stability is of paramount importance in football, from the perspective of clubs, players, and<br />

the public” <strong>FIFA</strong> Circular Letter 769.<br />

Contemporary football is caught between two very powerful concepts: the freedom of movement of players<br />

on the one side and contractual stability on the other. As it was shown in this research project, international<br />

migration has been part of football from the beginning. The decisions made by the European Court<br />

of Justice in relation to the Bosman case in 1995 entailed some large-scale changes in the transfer system<br />

of professional footballers. In particular, players who were EU or EEA nationals could now freely move<br />

within the European Union at the end of their contract as any transfer fees for out-of contract players were<br />

declared illegal. Second, the ‘3+2’ rule was abandoned for EU nationals. Certainly, these legal decisions<br />

have stimulated the freedom of movement of players. As can be observed from the profile of foreigners in<br />

the top 5 European leagues (England, Spain, Italy, Germany and Spain), cultural, historic and structural<br />

reasons continue to play a vital in the migration patterns of players. For example, whereas African players<br />

still constitute a comparatively high percentage of foreign players in France, many South American players<br />

are registered in the Italian Serie A and the Spanish Primera División. Another trend which has become<br />

visible is the decreasing age of the first international transfer of players. To counteract this development,<br />

<strong>FIFA</strong> has decisively restricted the transfer of minors under Article 19 of the Regulations on the Status and<br />

Transfer of Players.<br />

Professional footballers are rather ‘special employees’ as their value to clubs goes far beyond comparison<br />

to that of regular workers. Naturally, clubs must finance the acquisition and maintenance of these ‘assets’<br />

as to compete in an industry which shows a very diverging trend between big and small. It could be shown,<br />

that the five biggest European leagues are growing a lot faster than the rest. Currently, they alone account<br />

for 53% of the total European football market. Their growth is essentially fuelled by a combination of three<br />

income streams (broadcasting, commercial and matchday revenues). The same polarization could also be<br />

witnessed on individual club level where nineteen out of the top twenty most revenue producing clubs stem<br />

from the top five leagues. For middle sized and smaller clubs, alternative financial models include the cov-<br />

8

ering of losses through donations by the owner or, ultimately, the covering of losses through transfer activity.<br />

The latter holds particularly true for countries outside of Europe where the ‘big three’ income streams<br />

are not that pronounced and where many talented players are trained. It is needless to say that these clubs<br />

are keen to see their players in a stable contractual relationship.<br />

The main findings in relation to the financial strategies of clubs are based on a quantitative research which<br />

was conducted on European club level. According to their position in the UEFA association coefficient<br />

ranking, three peer groups of European leagues (one group each for ranks 1-10, 11-25 and 26-53) were<br />

created and tested on eventual differences in accordance to the answers obtained from a questionnaire sent<br />

out to the member clubs of these leagues. The main findings were that clubs from Eastern Europe, especially<br />

from the former Yugoslavia were particularly dependent on the income from transfer fees. The same holds<br />

true for some South American and African clubs which were punctually tested and used for reference. At the<br />

same time, clubs from the smallest European leagues are rather segregated in their transfer activity from<br />

the other leagues. The general importance of transfers for professional clubs was considered to be high as<br />

indicated by the respondent clubs. Interestingly, no significant differences between the three peer groups<br />

could be found. Some clubs include indemnity clauses in their players’ contracts in order to protect their<br />

contractual relationship. In this context, there was a significant difference between the three groups indicating<br />

that clubs from the better-ranked leagues more frequently make use of such a clause. Finally, it was<br />

found that youth development was considered to be very important for all respondent clubs generally indicating<br />

that the aim to reinforce the first team or substitute players was the most crucial. The aim of making<br />

a financial profit through future transfers and the identification with the local community followed second.<br />

The international governing body <strong>FIFA</strong> attempts to provide a universal guideline on how to deal with contractual<br />

stability and international mobility. One major challenge is the diversity of national regulations in<br />

sports which has internationalized rapidly. As was shown in the legal reference cases, there is often a fine<br />

line in setting the track for future decisions. Reference was made to three distinct legal problems: the player<br />

status, unilateral option clauses for the extension of players’ contracts and the unilateral breach of contract<br />

under Article 17 of the <strong>FIFA</strong> Regulations. The biggest problem in the definition of player status referred<br />

to the use of contracts designated as ‘scholarship agreement’, ‘apprenticeship contract’, etc. In essence,<br />

many clubs exposed themselves to a possible loss of the player by offering contracts which on first sight left<br />

it unclear if the player had to be considered amateur or professional. This was supported by differences<br />

in national legislation which either oblige clubs to use certain types of contracts or, at least, protect their<br />

validity. This protection is not given on an international level. The position of <strong>FIFA</strong> in this respect is clear:<br />

the remuneration is the only decisive criteria to determine player status.<br />

The use of unilateral options was found to be problematic in the sense that it destabilizes the equal bargaining<br />

power between the employer and the player. An analysis of the applicable reference cases revealed that<br />

unilateral options are in general terms not recognized by <strong>FIFA</strong> and the Court of Arbitration for Sports unless<br />

they incorporate some specific elements which work for the clear and acceptable advantage of the player.<br />

9

The unilateral breach of contract is a topic which received a lot of attention by associations, clubs, players<br />

and, ultimately, the media. The most recent reference cases from CAS (Webster, Soto Jaramillo, Mexès and<br />

Matuzalem) were analyzed under consideration of the particularities of each case. In the famous Webster<br />

case, the Panel based the compensation to be paid by the player and his new club on the sum of the salary<br />

payments of the player’s outstanding contractual period with the former club. This reasoning was later<br />

broadened in the other cases through the inclusion of various new aspects, e.g. a transfer offer prior to the<br />

breach (as in the Mexès case) or a buy-out clause in the player’s new contract (as in the Matuzalem case).<br />

Another important aspect which also leads to sporting sanctions is whether the player is under the protected<br />

period at the time of breach of contract as specified in Article17 of the <strong>FIFA</strong> RSTP. Yet the sentences<br />

so far have still left some of the issues unclear mainly because <strong>FIFA</strong> and CAS had to discover this rather<br />

new territory. The keyword ‘specificity of sport’ has been abundantly used to justify some of the decisions<br />

made. It remains to be seen what further developments in the legal regulations will bring. <strong>FIFA</strong>’s attempt<br />

to defend the actual player transfer system is certainly not easy in light of certain interferences with public<br />

and private law.<br />

In the meantime, clubs should attempt to defend themselves from any form of legal conflict. Following the<br />

recommendations made in the last part of the research, they should find themselves in a safer position to<br />

administer their players’ contracts and focus on some particularities in the current legal environment.<br />

Some clear recommendations were made in the sense that clubs should clearly define the status of their<br />

players. Further, the use of unilateral options should be avoided by clubs. Instead small remunerated contracts<br />

should be offered to youth players which can consequently be readjusted based on their performance.<br />

In regards to unilateral breach of contract, clubs should incorporate a variable indemnity clause in their<br />

players’ contract which will automatically adjust the compensation fee in relation to some objective criteria<br />

with respect to the performance of the player and the club. In this way the club can circumvent the mitigation<br />

risk inherent in a fixed buy-out clause. Frequent contract renewals are another means by which the<br />

club can assure to have its players constantly under the protected period.<br />

This project is not aimed at restricting the movement of players in general but to protect clubs financially<br />

when players decide to leave. Moreover, the strategy of many clubs is based on transfer activity, which actually<br />

implies the movement of players. Most importantly, this should be regulated in a uniform manner as<br />

not to damage certain clubs more than others. As the football industry is on its way to become increasingly<br />

professionalized, especially at the top end, smaller clubs should also have some means by which they can<br />

at least claim a financial compensation for their sporting losses.<br />

10

Indian League: A Suitable Product for T.V.?<br />

Gonzalo Bossart (Chilean/ Swiss)<br />

Manoel Medeiros Flores Junior (Brazilian)<br />

Pedro Presa Rodrigues (Portuguese)<br />

Taufique Ahmed (Indian)<br />

For long, T.V. has been perceived as the means to financially leverage most businesses, especially when it<br />

comes to an industry such as sport. Football is certainly one discipline that depends almost entirely on the<br />

power of T.V. Through T.V., brands are known, myths are born and value is created. Without this powerful<br />

marketing channel football’s impact in society would not be the same. Let’s take England as an example.<br />

After a long period of decline, English football saw in T.V. money the means to save the league and its image.<br />

These sums affected the league in every aspect and helped re-shape English society by once again putting<br />

the country in the centre of the world, though this time in football terms. Attendances at professional<br />

football matches have risen year-on-year and many of the Premier League games are regularly sold out.<br />

In addition, the revamped stadia that house clubs provide a much safer and more comfortable environment<br />

for spectators. On the pitch, the Premier League teams have proved successful in attracting big name overseas<br />

players, a stark contrast to the late 1980s when few wanted to be involved in English football. What is<br />

more, football’s new image appears to have been successful in attracting families back to football matches,<br />

with the hooliganism that dogged English football in the 1970s and 1980s seemingly on the decline. These<br />

direct and indirect effects of the commercialization of football through T.V. have been seen in every country<br />

where league success is constant.<br />

The United States could not be different where its leagues are known for their commercial value and international<br />

reach. Take the NBA for instance. NBA has created icons like Michael Jordan and possesses<br />

12 international offices. The league was one of the first to benefit from the positive marketing generated<br />

by T.V. exposure and the monetary gains derived from it 1 . If this success was not enough, the NBA is always<br />

searching for other markets and relies greatly on the awareness it created throughout these years of<br />

partnership with T.V. Coincidentally enough, India is NBA’s next target. As mentioned by NBA’s director<br />

of international development, ‘India is a significant emerging business and basketball opportunity for us’. 2<br />

England and the USA are certainly benchmarks when it comes to running and developing leagues, however,<br />

the advantage of both countries is the fact that the culture for the sports of their predominant leagues<br />

1 Mullin, B., Hardy, S., Sutton, W., March 19, 2007<br />

2 Yahoo Sports, Jun 21, 2009<br />

11

was already strong much before a professional approach. The challenge of this paper is to understand India,<br />

a country that suffers to develop its football mainly due to the lack of this strong traditional link to the<br />

sport and the predominance of another (cricket).<br />

In India We Trust…<br />

India is the 7th biggest country in the world in territory and the 2nd in population (1.2 billion people).<br />

With an emerging economy that grew at an average rate of 7% in the decade 1997-2007 3 , the country is<br />

seen by many as the ‘sleeping giant’ and benefits from a well-educated population that exports know-how<br />

throughout the globe. These characteristics are well-known by the general public. What is not well spread<br />

is India’s passion for football. Despite the clear differences between the country’s tradition in cricket and<br />

football, little is known of India’s early successes in the “people’s game”. The impact of this success led not<br />

only to the invitation to participate in a World Cup (1950), which was not accepted for several reasons, but<br />

also to ups and downs of India’s football in the subsequent years. The focus of this paper is to introduce the<br />

reader to a country that was colonized by the inventors of football but failed along the way. The reasons behind<br />

this failure and India’s present football structure will lead to an understanding of the drastic changes<br />

that the country must undergo in order to take football to the developmental heights of its economy. These<br />

changes, however, will be proven to be only viable and worthwhile with the aid of T.V. and everything that<br />

comes with it. Structural demands, tight financial and managerial control, infrastructure development and<br />

fan management are all issues that will be dealt with, using the T.V. perspective and its role as a catalyst of<br />

success in today’s sporting context.<br />

Independence or Death<br />

When dealing with structural demands, the approach will start with a thorough analysis of how India’s<br />

league (I-League) structure is designed and which are the implications of such. A recommendation taking<br />

into account some best practices in leagues (mainly Europeans) will follow as way to tailor an ideal football<br />

structure for a country like India. A league that today is placed under the federation and run with an<br />

amateur and bureaucratic approach has a limited opportunity for growth. With this idea in mind, a formula<br />

to separate the league taking into account examples of success in leagues such as, the “Premier League”<br />

(England) and “La Liga” (Spain), will be drawn. This new design will pave the way to the understanding<br />

of a need to have a body in charge of controlling key issues, such as licensing criteria, independent from the<br />

league itself. This body will be the engine of growth since it will keep track of the financial status of clubs<br />

and all other aspects of its (and league’s) life. A model based on the French league will be proposed and the<br />

independence of this organism will be explained in detail. Both the independence of the league and of this<br />

new body will become the cornerstones of a new reality in India’s football. However, for a complete attempt<br />

3 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/IN.html<br />

12

to make the I-League a solid institution with its focus in the development through T.V. investment, it will<br />

be necessary to suggest three matters that should be urgently tackled. In India’s case these urgent matters<br />

that will allow the league to be shaped in a T.V.-friendly manner are: competition, stadia and attendances.<br />

Urgent Matters<br />

Competition is a peculiarity of India and the solution to some key issues such as calendar and format will<br />

be proposed. When it comes to stadia and attendances, the real effect and benefit of T.V. to these aspects<br />

will be crucial for one’s understanding of the important role it play in the consolidation of a league when it<br />

comes not only to its image but to the relationship to potential broadcasters.<br />

Finally, two variables in this paper are unquestionable, India’s potential and the power of T.V. When properly<br />

adding them into the football equation, the results are deemed to be substantial. The ultimate goal of<br />

this paper is to see if T.V. is indeed a variable in today’s football scenario in India and if it is not, to devise<br />

recommendations in order to prepare the country for the eventual outburst of T.V. investment. The foundations<br />

are laid and work must be done so that India will awake and shake the world with its football as it<br />

does with its economy.<br />

13

Building a Bridge to Senior Level<br />

Competitions – A Case Study of the<br />

UEFA U-21 Championship<br />

Marc Schmidgall (French/ Swiss)<br />

Marcelo Orchis (Brazilian/ Italian)<br />

Tanya Ng Yuen (Canadian)<br />

Thomas Schneiter (Swiss)<br />

Sport affects the daily lives of every individual, whether it is through active participation or simply watching<br />

sport for entertainment. It has come a long way throughout the years with structures, policies and<br />

development procedures set in place to produce optimal performance and the highest quality of play from<br />

athletes.<br />

With all the advances in elite sport, the stages of development of an athlete before reaching their top national<br />

team or making the finals of the Olympic games or the football World Cup are becoming more and<br />

more crucial. For this reason we find it important to examine carefully the different athlete development<br />

models and the professional direction which sport has undertaken in an attempt to clarify youth competitions<br />

from senior level ones. But what do the terms ‘youth’, ‘junior’, and ‘senior’ stand for? Are they<br />

clearly defined within the world of sport? Are they based on physical or psychological age? Within sport do<br />

the three distinct categories even exist? And if so how are these competition categories and championships<br />

organized? Throughout our paper we will address these questions and propose recommendations based on<br />

our empirical research.<br />

Our main proposal primarily involves the case of UEFA’s European Under-21 Championship. The specifics<br />

of the Under-21 Championship are ideal to put under the microscope of our analysis because both the<br />

age group of athletes who participate in this category and the competition itself are not clearly defined.<br />

Take for example the name of the competition, UEFA’s European Under-21 Championship, why is the name<br />

of the competition called Under-21 when players can be up to 23 years of age? Does UEFA consider this<br />

championship to be youth or senior? There are many questions surrounding this specific tournament.<br />

In order to have a better understanding of the perception of the current sporting scene we have divided our<br />

paper into two sections:<br />

14

The first section paints the picture of sport in general through which various development chains for competition<br />

are analyzed. Discussed are the various models used around the world. It also includes an overview<br />

regarding the status of professionalism and amateurism and ends with an overview of other team sports and<br />

their competition portfolio.<br />

The second part of our paper reviews the specifics of UEFA’s European Under-21 Championship case. In<br />

order to get a better understanding from our key stakeholder within the competition – participating National<br />

Football Associations - we formatted a research study. Our methodology was encompassed through<br />

a series of detailed questions in a questionnaire format which was initiated via telephone interview as well<br />

as an on-site visit to the 2009 European Under-21 Championships hosted in Sweden.<br />

Our research included understanding the structures of National Associations, such as the perception internally<br />

of their Under-21 team as well as National Association’s perception of UEFA’s European Under-21<br />

tournament overall. As one of the main players in football, National Associations opinions regarding this<br />

tournament are essential because without them bringing forth highly skilled players or investing in their<br />

football programs such a tournament would not exist. For our group this is a key topic of interest as we<br />

have not seen much research done regarding the emphasis and value put on the perception of a National<br />

Association.<br />

The information gained was vital as it also lead to doing a further comparison with regards to the core<br />

values UEFA was emitting regarding the Championship to its members. The study from the 2007 edition<br />

of the UEFA European Championship Final Tournament in the Netherlands concluded with UEFA designing<br />

five core values attributed to the Championship, which include: Excellence, Aspiration, Accessibility,<br />

Entertainment and Fresh & Fun. These values are the heart of the tournament, however do the National<br />

Associations attribute the importance of these vales to the tournament also? Are National Associations on<br />

the same page as UEFA? If not, is UEFA effectively explaining their position about the tournament?<br />

Our site visit to Sweden was essential as it allowed us to observe first hand how the tournament had evolved<br />

professionally, and to further support findings from previous research and statistics. UEFA itself was of<br />

great help in providing important and useful information regarding the competition and providing support<br />

of this research overall.<br />

Our aim is to be able to show how the National Associations perceive Under-21 Championship, and give<br />

importance to this category from within. Furthermore, based on our findings from the in-depth interviews<br />

with National Associations and through an analysis of the competition itself we would like to provide practical<br />

recommendations regarding the age category within football as a whole. The case of UEFA’s U-21 European<br />

Championship allows us to understand the realities of an important tournament and its stakeholder.<br />

15

From a National Association point of view understanding the development process and the difference between<br />

youth and senior competitions is a huge task and even more so coordinating a successful program<br />

which allows athletes to find that link in bridging and developing from a grassroots to an elite professional.<br />

The tournament’s slogan ‘Stars of today, superstars of tomorrow’, best describes the overview of the Championship<br />

and it’s role within the development process of athletes and national player development structures.<br />

As mentioned by the Scottish Football Association when asked about the importance of the U21<br />

category in the development of an athlete’s career:<br />

“I think that most people would agree that they are not a real youth team. When players<br />

get to the age of 20 – 21, they are adults and so therefore it does help to close that<br />

gap U19 to the international level. I think that it’s a very important level”(Scotland). 1<br />

We believe that the term ‘bridging’ is a key word in closing the gap and links our entire research. At every<br />

stage a ‘bridge’ is built connecting youth to senior competition. By encompassing this term within the parameters<br />

of our research on UEFA’s European Under-21 Championship and the age category in which it<br />

finds itself we will be able to discuss and clarify the classification of this unique tournament in the world<br />

of football.<br />

1 Interview on 13th May 2009 with Billy Stark (The Scottish Football Association).<br />

16

The <strong>International</strong> Positioning of an<br />

European Football League as a TV Product:<br />

The Cases of the English Premier League,<br />

Spanish Liga and Italian Serie A<br />

Eden Ghebresellassie (Eritrean/ Italian)<br />

Elaine Kosmas (Greek/ Canadian)<br />

Hichem Abdelkader Boughrara (Algerian)<br />

Kasra Asrar Haghighi (Canadian/ Iranian)<br />

Kim Dae Up (South Korean)<br />

The objective of this work was to find the best possible model to position a football league as a successful TV<br />

product internationally, with focus on the Italian Seria A. the case studies involved in this project are: English<br />

Premier League, Spanish La Liga, Italian Serie A, German Bundesliga and French Ligue 1.<br />

As stated throughout the project, TV and football together have become a powerful driving force in these<br />

current times. Football has always drawn the attention of many people, of different age, color, race, religion<br />

and background. Television has been able to capitalize on those people’s passion, interest, and involvement<br />

and eager by serving them “the product of football” the way they wanted it and how they wanted<br />

it. So basically, football viewers are television “clients”, TV is a football “client”, since the more viewers<br />

the more money and finally football is the viewers’ “client”.<br />

Since the motto is: “the client is always right” and nowadays, for a football league to be successful it has<br />

to acquire a relevant international “clientele”, an extensive research was done in order to understand the<br />

studies done before and realize what could have been added.<br />

The literary review was based on the “big five” European football leagues. Through the literary research<br />

and specifically seven variables kept on surfacing. These variables are: Scheduling, Broadcast Production<br />

(Monitoring Product Control), Government Regulations, Stadia, Leagues’ Personnel Knowledge of Selling<br />

TV Rights, League Marketing, Game Entertainment Value. These variables are important under the<br />

national and international aspect of a football league. If each of these variables are mastered or at least<br />

taken in consideration very seriously by any league, the results can be of a consistent and long lasting successful<br />

to a football league.<br />

17

To support the research qualitative research was done, through the submission of a questionnaire to different<br />

stakeholders who are involved everyday with the nexus of football, viewers and media. These stakeholders<br />

are the football leagues themselves, the broadcasting agencies that are usually “the middle man”<br />

between the sport product and TV, along with some football organizations, such as UEFA. Their feedback<br />

was very important to understand or reiterate the level of importance of the variables found in regards to<br />

each league from their different prospective.<br />

Then, Focus Groups were held with groups of people categorized in respect to their provenience and interest<br />

for football. The outcome of these focus groups was a “raw” but first hand direct collection of the<br />

opinions, ideas, suggestions, feelings and critics viewers held in regards to the top five European leagues.<br />

It was a great way to establish if the “client” is in fact satisfied; and if it is not, how to do so.<br />

In the written questionnaire the main variables found during the literary review were obviously mentioned<br />

and brought to the attention of the person, but in the case of the focus groups the variables were not clearly<br />

stated by the facilitator. It was very interesting to see how the issues or positive reasoning’s of the respondents<br />

for watching or not watching a specific football league were supported by those same variables.<br />

The separate analysis of each football league under the natural structure given by listing each variable set<br />

a great platform to be able to come up with an ideal model on how to position a football league as a successful<br />

TV product internationally.<br />

By the current UEFA Country Ranking, the leagues’ success is listed in such order: first the EPL, second La<br />

Liga, Serie A, Bundesliga and Ligue 1. This gives an indication of how well these leagues are serving their<br />

clients. However, this does not mean each league is not without its own strengths and weaknesses. There is<br />

always room to improve and be innovative to improve a league’s strategy and hence positioning.<br />

Although many long-term strategies have been presented before our the main focus has been on short-term<br />

changes that do not require long-term investment strategies. The recommendations sought were elements<br />

that could easily be implemented without committing large amounts of sums. Our findings resulted in a<br />

number of recommendations and will be presented according to the variable they align with.<br />

First, the scheduling of the game was considered to be the first priority, which is not hard to understand. A<br />

league with international hopes must insure the timing of their live match in their local time zone, also has<br />

a favorable airing in the markets they have targeted. Unfortunately airtime is limited on major channels<br />

and there is hesitation by broadcasters to not introduce sport at times when other major viewing audiences<br />

are targeted. Having said this, it is important of the league to be able to negotiate well with broadcasters<br />

in the common goal of securing the best possible times to increase a league audience without isolating the<br />

broadcasters’ other viewers.<br />

18

Second, The leagues’ personnel knowledge of selling TV rights is necessary to be able to market and sell<br />

the audio-visual rights effectively and in line with the league’s overall strategy. An investment in human<br />

capital is required in this area.<br />

Third, the game entertainment value should consistently be developed to attract and hold viewer’s attention.<br />

Within the leagues, offensive style of play and consistent flow of play are most entertaining. However,<br />

short of telling clubs to play offensively this can be rather difficult to implement, but should be considered.<br />

The areas with the most opportunity are the preview, post and highlight shows. Viewers like a build up to the<br />

game, with information on other teams in the league and about the up coming game. The highlight shows<br />

should concentrate on showing game footage as opposed to long roundtable discussions and opinions of<br />

commentators. Based on the research viewers prefer game footage with commentary, not round tables. In<br />

addition, international players and coaches make the league more dynamic and entertaining. The supplementary<br />

benefit of this is the increase in viewership in the country of origin of the national players.<br />

Fourth, broadcast production is necessary for a quality product. Although it is argued the product is football<br />

and this is where the quality is derived from, if the signal and production are not of good quality the<br />

perception of the league becomes lower. Similar to a product that is nicely packaged, the same holds true<br />

for a football game on television. The league needs to make an investment here or outsource this area. It is<br />

critical for the quality and worldwide reach. Supplementary, the emergence of new media platforms such<br />

as Internet and mobile technology should also be leverage here.<br />

Fifthly league marketing is essential to the proliferation of the league internationally. Here the league must<br />

manage the media nexus and proactively supply media outlets (TV, newspaper, radio, magazine, internet,<br />

mobile) with results, information, clips, pictures and interviews. An open communication channel is necessary<br />

and a laid out media plan with objectives helps to implements this. Building on this, a consistent game<br />

format should be implemented across the league to assist in branding with multiple opportunities for the<br />

media to take pictures, have interviews and record footage. The end result here would be a consistent coverage<br />

of the sports event that becomes recognizable to the viewer.<br />

Sixthly, Stadia are identified. Although it would be ideal for our clubs to play at state of the art stadia, it is<br />

an unrealistic recommendation. Instead, the focus here should be on the media. All stadia should be television<br />

adapted with positions for many cameras, media areas and uploading facilities. As mentioned earlier,<br />

the media play an important role in how the league is perceived internationally. Similar to a guest coming<br />

to your home and would like to made to feel comfortable, the same rings true for media. As much care and<br />

accommodation as possible should be given to the media, as they will be writing independent reviews of the<br />

league and it is in the league’s interest for the media to have a good working experience.<br />

19

Lastly, government regulations are seen as a factor that affects the league’s internationalization. This has<br />

mostly been documented in the way a league sells their TV rights. The regulations inhibit the way a league<br />

would like to commercialize, especially within the European Union. Here a recommendation of working<br />

with the government and showing the benefit of the general public is achieved through the league’s selling<br />

strategies. Although it might always be the goal to make the most money, more could be achieved by being<br />

proactive and not greedy in limiting your product to reap financial rewards. This strategy has worked in the<br />

past; however, more and more, consumers are less willing to pay a premium unless the product is perceived<br />

as the best. For sake of internationalizing, the more people see the league, the more they will watch it.<br />

20