The Editors - Third World Network

The Editors - Third World Network

The Editors - Third World Network

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

W O M E N<br />

‘Matriarch’ leads struggle to<br />

recover stolen land<br />

A 69-year-old matriarch in Colombia’s poorest province has been leading the<br />

struggle by her community since 2000 to recover land illegally expropriated by the<br />

country’s paramilitary groups in complicity with the Colombian state. Constanza<br />

Viera recounts the harrowing story of a marginalised community’s continuing<br />

struggle for justice.<br />

‘GOD willing, we will make it,’ reads<br />

the sign on a rusty old all-terrain vehicle,<br />

ideal for the complicated drive<br />

to the remote Curbaradó river valley<br />

in the banana-producing region of<br />

Urabá in northwest Colombia.<br />

This area is part of the jungle<br />

province of Chocó, one of the world’s<br />

most biodiverse places until it was<br />

drawn into the armed conflict between<br />

left-wing guerrillas and government<br />

forces – and, since the 1980s, far-right<br />

paramilitary militias – that has<br />

plagued Colombia for nearly half a<br />

century.<br />

Inter Press Service (IPS) travelled<br />

to this isolated region with documentary-makers<br />

from Justice for Colombia,<br />

a coalition founded in 2002 by<br />

the British trade union movement in<br />

response to murders of labour activists<br />

and the overall humanitarian crisis<br />

in Colombia.<br />

<strong>The</strong> killings in Urabá began in<br />

1995, and the major paramilitary offensive<br />

started in 1996. ‘This has all<br />

changed so much that it looks completely<br />

different now. Everything has<br />

been destroyed: the trees, the jungle,<br />

the rivers, the streams,’ says María<br />

Chaverra, 69.<br />

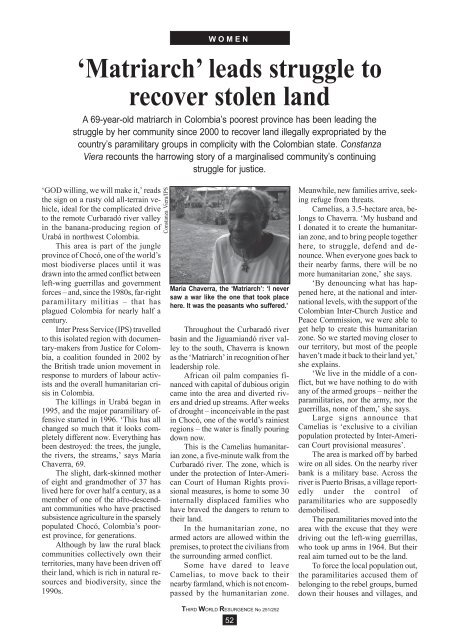

<strong>The</strong> slight, dark-skinned mother<br />

of eight and grandmother of 37 has<br />

lived here for over half a century, as a<br />

member of one of the afro-descendant<br />

communities who have practised<br />

subsistence agriculture in the sparsely<br />

populated Chocó, Colombia’s poorest<br />

province, for generations.<br />

Although by law the rural black<br />

communities collectively own their<br />

territories, many have been driven off<br />

their land, which is rich in natural resources<br />

and biodiversity, since the<br />

1990s.<br />

Constanza Viera/IPS<br />

María Chaverra, the ‘Matriarch’: ‘I never<br />

saw a war like the one that took place<br />

here. It was the peasants who suffered.’<br />

Throughout the Curbaradó river<br />

basin and the Jiguamiandó river valley<br />

to the south, Chaverra is known<br />

as the ‘Matriarch’ in recognition of her<br />

leadership role.<br />

African oil palm companies financed<br />

with capital of dubious origin<br />

came into the area and diverted rivers<br />

and dried up streams. After weeks<br />

of drought – inconceivable in the past<br />

in Chocó, one of the world’s rainiest<br />

regions – the water is finally pouring<br />

down now.<br />

This is the Camelias humanitarian<br />

zone, a five-minute walk from the<br />

Curbaradó river. <strong>The</strong> zone, which is<br />

under the protection of Inter-American<br />

Court of Human Rights provisional<br />

measures, is home to some 30<br />

internally displaced families who<br />

have braved the dangers to return to<br />

their land.<br />

In the humanitarian zone, no<br />

armed actors are allowed within the<br />

premises, to protect the civilians from<br />

the surrounding armed conflict.<br />

Some have dared to leave<br />

Camelias, to move back to their<br />

nearby farmland, which is not encompassed<br />

by the humanitarian zone.<br />

Meanwhile, new families arrive, seeking<br />

refuge from threats.<br />

Camelias, a 3.5-hectare area, belongs<br />

to Chaverra. ‘My husband and<br />

I donated it to create the humanitarian<br />

zone, and to bring people together<br />

here, to struggle, defend and denounce.<br />

When everyone goes back to<br />

their nearby farms, there will be no<br />

more humanitarian zone,’ she says.<br />

‘By denouncing what has happened<br />

here, at the national and international<br />

levels, with the support of the<br />

Colombian Inter-Church Justice and<br />

Peace Commission, we were able to<br />

get help to create this humanitarian<br />

zone. So we started moving closer to<br />

our territory, but most of the people<br />

haven’t made it back to their land yet,’<br />

she explains.<br />

‘We live in the middle of a conflict,<br />

but we have nothing to do with<br />

any of the armed groups – neither the<br />

paramilitaries, nor the army, nor the<br />

guerrillas, none of them,’ she says.<br />

Large signs announce that<br />

Camelias is ‘exclusive to a civilian<br />

population protected by Inter-American<br />

Court provisional measures’.<br />

<strong>The</strong> area is marked off by barbed<br />

wire on all sides. On the nearby river<br />

bank is a military base. Across the<br />

river is Puerto Brisas, a village reportedly<br />

under the control of<br />

paramilitaries who are supposedly<br />

demobilised.<br />

<strong>The</strong> paramilitaries moved into the<br />

area with the excuse that they were<br />

driving out the left-wing guerrillas,<br />

who took up arms in 1964. But their<br />

real aim turned out to be the land.<br />

To force the local population out,<br />

the paramilitaries accused them of<br />

belonging to the rebel groups, burned<br />

down their houses and villages, and<br />

THIRD WORLD RESURGENCE No 251/252<br />

52