THE YANKEE COMANDANTE

THE YANKEE COMANDANTE

THE YANKEE COMANDANTE

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

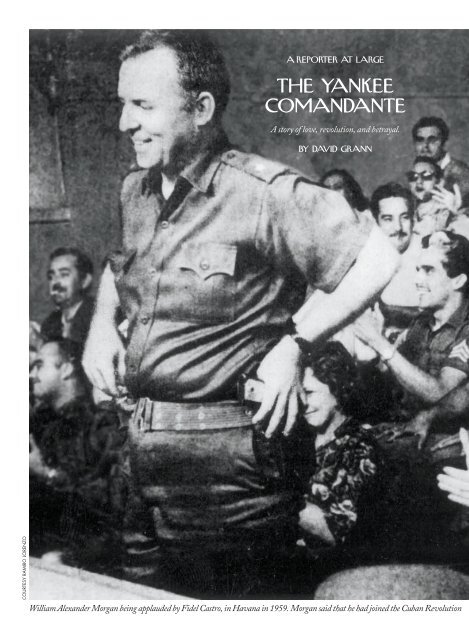

A REPORTER AT LARGE<br />

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>YANKEE</strong><br />

<strong>COMANDANTE</strong><br />

A story of love, revolution, and betrayal.<br />

BY DAVID GRANN<br />

COURTESY RAMIRO LORENZO<br />

William Alexander Morgan being applauded by Fidel Castro, in Havana in 1959. Morgan said that he had joined the Cuban Revolution

ecause “the most important thing for free men to do is to protect the freedom of others.”<br />

For a moment, he was obscured by the<br />

Havana night. It was as if he were invisible,<br />

as he had been before coming to<br />

Cuba, in the midst of revolution. Then a<br />

burst of floodlights illuminated him:<br />

William Alexander Morgan, the great<br />

Yankee comandante. He was standing,<br />

with his back against a bullet-pocked<br />

wall, in an empty moat surrounding La<br />

Cabaña—an eighteenth-century stone<br />

fortress, on a cliff overlooking Havana<br />

Harbor, that had been converted into a<br />

prison. Flecks of blood were drying on<br />

the patch of ground where Morgan’s<br />

friend had been shot, moments earlier.<br />

Morgan, who was thirty-two, blinked<br />

into the lights. He faced a firing squad.<br />

The gunmen gazed at the man they<br />

had been ordered to kill. Morgan was<br />

nearly six feet tall, and had the powerful<br />

arms and legs of someone who had survived<br />

in the wild. With a stark jaw, a pugnacious<br />

nose, and scruffy blond hair, he<br />

had the gallant look of an adventurer in a<br />

movie serial, of a throwback to an earlier<br />

age, and photographs of him had appeared<br />

in newspapers and magazines<br />

around the world. The most alluring images—taken<br />

when he was fighting in the<br />

mountains, with Fidel Castro and Che<br />

Guevara—showed Morgan, with an untamed<br />

beard, holding a Thompson submachine<br />

gun. Though he was now<br />

shaved and wearing prison garb, the executioners<br />

recognized him as the mysterious<br />

Americano who once had been hailed<br />

as a hero of the revolution.<br />

It was March 11, 1961, two years after<br />

Morgan had helped to overthrow the dictator<br />

Fulgencio Batista, bringing Castro<br />

to power. The revolution had since fractured,<br />

its leaders devouring their own, like<br />

Saturn, but the sight of Morgan before a<br />

firing squad was a shock. In 1957, when<br />

Castro was still widely seen as fighting for<br />

democracy, Morgan had travelled from<br />

Florida to Cuba and headed into the jungle,<br />

joining a guerrilla force. In the words<br />

of one observer, Morgan was “like Holden<br />

Caulfield with a machine gun.” He was<br />

the only American in the rebel army and<br />

the sole foreigner, other than Guevara, an<br />

Argentine, to rise to the army’s highest<br />

rank, comandante.<br />

After the revolution, Morgan’s role in<br />

Cuba aroused even greater fascination, as<br />

the island became enmeshed in the larger<br />

battle of the Cold War. An American<br />

who knew Morgan said that he had<br />

<strong>THE</strong> NEW YORKER, MAY 28, 2012 47

served as Castro’s “chief cloak-and-dagger<br />

man,” and Time called him Castro’s<br />

“crafty, U.S.-born double agent.”<br />

Now Morgan was charged with conspiring<br />

to overthrow Castro. The Cuban<br />

government claimed that Morgan had<br />

actually been working for U.S. intelligence—that<br />

he was, in effect, a triple<br />

agent. Morgan denied the allegations,<br />

but even some of his friends wondered<br />

who he really was, and why he had come<br />

to Cuba.<br />

Before Morgan was led outside La<br />

Cabaña, an inmate asked him if there was<br />

anything he could do for him. Morgan<br />

replied, “If you ever get out of here alive,<br />

which I doubt you will, try to tell people<br />

my story.” Morgan grasped that more<br />

than his life was at stake: the Cuban regime<br />

would distort his role in the revolution,<br />

if not excise it from the public record,<br />

and the U.S. government would<br />

stash documents about him in classified<br />

files, or “sanitize” them by concealing<br />

passages with black ink. He would be<br />

rubbed out—first from the present, then<br />

from the past.<br />

The head of the firing squad shouted,<br />

“Attention!” The gunmen raised their<br />

Belgian rifles. Morgan feared for his wife,<br />

Olga—whom he had met in the mountains—and<br />

for their two young daughters.<br />

He had always managed to bend the<br />

“Wider.”<br />

• •<br />

forces of history, and he had made a lastminute<br />

plea to communicate with Castro.<br />

Morgan had believed that the man he<br />

once called his “faithful friend” would<br />

never kill him. But now the executioners<br />

were cocking their guns.<br />

<strong>THE</strong> FIRST TRICK<br />

When Morgan arrived in Havana, in<br />

December, 1957, he was propelled<br />

by the thrill of a secret. He made<br />

sure that he wasn’t being followed as he<br />

moved surreptitiously through the neonlit<br />

capital. Advertised as the “Playland of<br />

the Americas,” Havana offered one<br />

temptation after another: the Sans Souci<br />

night club, where, on outdoor stages,<br />

dancers with frank hips swayed under the<br />

stars to the cha-cha; the Hotel Capri,<br />

whose slot machines spat out American<br />

silver dollars; and the Tropicana, where<br />

guests such as Elizabeth Taylor and<br />

Marlon Brando enjoyed lavish revues<br />

featuring the Diosas de Carne, or “flesh<br />

goddesses.”<br />

Morgan, then a pudgy twenty-nineyear-old,<br />

tried to appear as just another<br />

man of leisure. He wore a two-hundredand-fifty-dollar<br />

white suit with a white<br />

shirt, and a new pair of shoes. “I looked<br />

like a real fat-cat tourist,” he later joked.<br />

But, according to members of Morgan’s<br />

inner circle, and to the unpublished<br />

account of a close friend, he avoided the<br />

glare of the city’s night life, making his<br />

way along a street in Old Havana, near a<br />

wharf that offered a view of La Cabaña,<br />

with its drawbridge and moss-covered<br />

walls. Morgan paused by a telephone<br />

booth, where he encountered a Cuban<br />

contact named Roger Rodríguez. A<br />

raven-haired student radical with a thick<br />

mustache, Rodríguez had once been shot<br />

by police during a political demonstration,<br />

and he was a member of a revolutionary<br />

cell.<br />

Most tourists remained oblivious of<br />

the many iniquities of Cuba, where people<br />

often lived without electricity or running<br />

water. Graham Greene, who published<br />

“Our Man in Havana” in 1958,<br />

later recalled, “I enjoyed the louche atmosphere<br />

of Batista’s city and I never stayed<br />

long enough to become aware of the sad<br />

political background of arbitrary imprisonment<br />

and torture.” Morgan, however,<br />

had briefed himself on Batista, who had<br />

seized power in a coup, in 1952: how the<br />

dictator liked sitting in his palace, eating<br />

sumptuous meals and watching horror<br />

films, and how he tortured and killed dissidents,<br />

whose bodies were sometimes<br />

dumped in fields, with their eyes gouged<br />

out or their crushed testicles stuffed in<br />

their mouths.<br />

Morgan and Rodríguez resumed<br />

walking through Old Havana, and began<br />

a furtive conversation. Morgan was rarely<br />

without a cigarette, and typically communicated<br />

through a haze of smoke. He<br />

didn’t know Spanish, but Rodríguez<br />

spoke broken English. They had previously<br />

met in Miami, becoming friends,<br />

and Morgan believed that he could trust<br />

him. Morgan confided that he planned to<br />

sneak into the Sierra Maestra, a mountain<br />

range on Cuba’s remote southeastern<br />

coast, where revolutionaries had taken up<br />

arms against the regime. He intended to<br />

enlist with the rebels, who were commanded<br />

by Fidel Castro.<br />

The name of Batista’s mortal enemy<br />

carried the jolt of the forbidden. On November<br />

25, 1956, Castro, a thirty-yearold<br />

lawyer and the illegitimate son of a<br />

prosperous landowner, had launched<br />

from Mexico an amphibious invasion of<br />

Cuba, along with eighty-one self-styled<br />

commandos, including Che Guevara.<br />

After their battered wooden ship ran<br />

aground, Castro and his men waded<br />

48 <strong>THE</strong> NEW YORKER, MAY 28, 2012

through chest-deep waters, and came<br />

ashore in a swamp whose tangled vegetation<br />

tore their skin. Batista’s Army<br />

soon ambushed them, and Guevara was<br />

shot in the neck. (He later wrote, “I immediately<br />

began to wonder what would<br />

be the best way to die, now that all<br />

seemed lost.”) Only a dozen or so rebels,<br />

including the wounded Guevara and<br />

Castro’s younger brother, Raúl, escaped,<br />

and, exhausted and delirious with<br />

thirst—one drank his own urine—they<br />

fled into the steep jungles of the Sierra<br />

Maestra.<br />

Morgan told Rodríguez that he had<br />

been tracking the progress of the uprising.<br />

After Batista mistakenly declared<br />

that Castro had died in the ambush, Castro<br />

allowed a Times correspondent, Herbert<br />

Matthews, to be escorted into the Sierra<br />

Maestra. A close friend of Ernest<br />

Hemingway, Matthews longed not<br />

merely to cover world-changing events<br />

but to make them, and he was captivated<br />

by the tall rebel leader, with his wild beard<br />

and burning cigar. “The personality of the<br />

man is overpowering,” Matthews wrote.<br />

“Here was an educated, dedicated fanatic,<br />

a man of ideals, of courage.” Matthews<br />

concluded that Castro had “strong ideas<br />

of liberty, democracy, social justice, the<br />

need to restore the Constitution.” On<br />

February 24, 1957, the story appeared on<br />

the paper’s front page, intensifying the rebellion’s<br />

romantic aura. Matthews later<br />

put it this way: “A bell tolled in the jungles<br />

of the Sierra Maestra.”<br />

Yet why would an American be willing<br />

to die for Cuba’s revolution? When<br />

Rodríguez pressed Morgan, he indicated<br />

that he wanted to be both on the side of<br />

good and on the edge of danger, but he<br />

also wanted something else: revenge.<br />

Morgan said that he had an American<br />

buddy who had travelled to Havana and<br />

been killed by Batista’s soldiers. Later,<br />

Morgan provided more details to others<br />

in Cuba: his friend, a man named Jack<br />

Turner, had been caught smuggling<br />

weapons to the rebels, and was “tortured<br />

and tossed to the sharks by Batista.”<br />

Morgan told Rodríguez that he had<br />

already made contact with another revolutionary,<br />

who had arranged to sneak him<br />

into the mountains. Rodríguez was taken<br />

aback: the supposed rebel was an agent of<br />

Batista’s secret police. Rodríguez warned<br />

Morgan that he’d fallen into a trap.<br />

Rodríguez, fearing for Morgan’s life,<br />

offered to help him. He could not transport<br />

Morgan to the Sierra Maestra, but<br />

he could take him to the camp of a rebel<br />

group in the Escambray Mountains,<br />

which cut across the central part of the<br />

country. These guerrillas were opening a<br />

new front, and Castro welcomed them to<br />

the “common struggle.”<br />

Morgan set out with Rodríguez and a<br />

driver on the two-hundred-and-seventeen<br />

mile journey. As Aran Shetterly details<br />

in his incisive biography “The Americano”<br />

(2007), the car soon arrived at a<br />

military roadblock. A soldier peered inside<br />

at Morgan in his gleaming suit, the<br />

only outfit that he seemed to own. Morgan<br />

knew what would happen if he were<br />

seized—as Guevara said, “in a revolution,<br />

one wins or dies”—and he had prepared<br />

a cover story, in which he was an American<br />

businessman on his way to see coffee<br />

plantations. After hearing the tale, the<br />

soldier let them pass, and Morgan and his<br />

conspirators roared up the road, up into<br />

the Escambray, where the air became<br />

cooler and thinner, and where the threethousand-foot<br />

peaks had an eerie purple<br />

tint.<br />

Morgan was taken to a safe house to<br />

rest, then driven to a mountainside near<br />

the town of Banao. A peasant shepherded<br />

Morgan and Rodríguez through<br />

vines and banana leaves until they reached<br />

a remote clearing, flanked by steep slopes.<br />

The peasant made a birdlike sound,<br />

which rang through the forest and was<br />

reciprocated by a distant whistle. A sentry<br />

emerged, and Morgan and Rodríguez<br />

were led to a campsite strewn with water<br />

basins and hammocks and a few antiquated<br />

rifles. Morgan could count only<br />

thirty or so men, many of whom appeared<br />

barely out of high school and had the<br />

emaciated, straggly look of shipwreck<br />

survivors.<br />

The rebels regarded Morgan uncertainly.<br />

Max Lesnik, a Cuban journalist in<br />

charge of the organization’s propaganda,<br />

soon met up with the group, and recalls<br />

wondering if Morgan was “some kind of<br />

agent from the C.I.A.”<br />

Since the Spanish-American War, the<br />

U.S. had often meddled in Cuban affairs,<br />

treating the island like a colony. President<br />

Dwight D. Eisenhower had blindly supported<br />

Batista—believing that he would<br />

“deal with the Commies,” as he put it to<br />

Vice-President Richard Nixon—and the<br />

C.I.A. had activated operatives throughout<br />

the island. In 1954, in a classified report,<br />

an American general advised that if<br />

the U.S. was to survive the Cold War it<br />

needed to “learn to subvert, sabotage, and<br />

destroy our enemies by more clever, more<br />

sophisticated, and more effective methods<br />

than those used against us.” The<br />

C.I.A. went so far as to hire a renowned<br />

magician, John Mulholland, to teach operatives<br />

sleight of hand and misdirection.<br />

Mulholland produced two illustrated<br />

manuals, which referred to covert operations<br />

as “tricks.”<br />

As the C.I.A. tried to assess the threat<br />

to Batista, its operatives attempted to<br />

penetrate rebel forces in the mountains.<br />

Among other things, agents were believed<br />

to have recruited, or posed as, reporters.<br />

Mulholland advised operatives<br />

that “even more practice is needed to act<br />

a lie skillfully than is required to tell one.”<br />

The rebels also had to be sure that<br />

Morgan was not a K.G.B. operative, or a<br />

mercenary working for Batista’s military<br />

intelligence. In the Sierra Maestra, Castro<br />

had recently discovered that a peasant<br />

within his ranks was an Army informant.<br />

The peasant, after being summoned,<br />

dropped to his knees, begging that the<br />

revolution take care of his children. Then<br />

he was shot in the head.<br />

Morgan was now brought to see the<br />

commander of the rebel group,<br />

Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo. Twenty-three<br />

years old, soft-spoken, and bone-thin,<br />

Menoyo had a long, handsome face that<br />

was shielded by dark spectacles and a<br />

beard, giving him the look of a fugitive.<br />

The C.I.A. later noted, in its file on him,<br />

that he was an intelligent, capable young<br />

man who would not break “under normal<br />

interrogating techniques.”<br />

As a boy, Menoyo had emigrated<br />

from Spain—a lisp was faintly present<br />

when he spoke Spanish—and he had inherited<br />

his family’s militant posture toward<br />

tyranny. His oldest brother had<br />

been killed, at the age of sixteen, fighting<br />

<strong>THE</strong> NEW YORKER, MAY 28, 2012 49

the Fascists during the Spanish Civil<br />

War. His other brother, who had also<br />

come to Cuba, had been gunned down<br />

while leading a doomed assault on Batista’s<br />

palace, in 1957. Menoyo had identified<br />

the body at a Havana morgue before<br />

heading into the mountains. “I wanted<br />

to continue the fight in my brother’s<br />

name,” he recalls.<br />

Through a translator, Morgan told<br />

Menoyo his story about wanting to<br />

avenge a buddy’s death. Morgan said that<br />

he had served in the U.S. Army and was<br />

skilled in martial arts and hand-to-hand<br />

combat, and that he could train the inexperienced<br />

rebels in guerrilla warfare.<br />

There was more to fighting than shooting<br />

a rifle, Morgan argued; as he later<br />

said, with the right tactics they could put<br />

“the fear of God” in the enemy. To demonstrate<br />

his prowess, Morgan borrowed<br />

a knife and flicked it at a tree at least<br />

twenty yards away. It hit the target so<br />

squarely that some rebels gasped.<br />

That evening, they argued over<br />

whether Morgan could stay. Morgan<br />

seemed simpático—“like a Cuban,” as<br />

Lesnik puts it. But many rebels, fearing<br />

that he was an infiltrator, wanted to send<br />

Morgan back to Havana. The group’s<br />

chief of intelligence, Roger Redondo, recalls,<br />

“We did everything possible to make<br />

him leave.” During the next several days,<br />

they marched him endlessly up and down<br />

the mountainsides. Morgan was so fat,<br />

one rebel joked, that he had to be C.I.A.<br />

Morgan, famished and fatigued, repeatedly<br />

hollered a few Spanish words<br />

that he had learned, “No soy mulo”—“I’m<br />

not a mule!” At one point, the rebels led<br />

him into a patch of prickly poisonous<br />

shrubs, which stung like wasps and<br />

caused his chest and face to become<br />

grievously inflamed. Morgan could no<br />

longer sleep at night. When he removed<br />

his sweaty white shirt, Redondo recalls,<br />

“We pitied him. He was so fair-skinned<br />

and had turned such an angry red.”<br />

Morgan’s body also offered clues to a<br />

violent past. He had burn marks on his<br />

right arm, and a nearly foot-long scar ran<br />

across his chest, suggesting that someone<br />

had slashed him with a knife. There was<br />

a tiny scar under his chin, another by his<br />

left eye, and several on his left foot. It was<br />

as if he had already suffered years of hardship<br />

in the jungle.<br />

Morgan endured whatever ordeal the<br />

rebels subjected him to, shedding thirtyfive<br />

pounds along the way. He later wrote<br />

that he had become unrecognizable: “I<br />

weigh only—165 lbs and have a beard.”<br />

Redondo says, “The gringo was tough,<br />

and the armed men of the Escambray<br />

came to admire his persistence.”<br />

Several weeks after Morgan arrived,<br />

a lookout noticed something moving<br />

amid distant cedars and tropical plants.<br />

Using binoculars, he made out six men,<br />

in khaki uniforms and wide-brimmed<br />

hats, carrying Springfield rifles. A Batista<br />

Army patrol.<br />

Most of the rebels had never faced<br />

combat. Morgan later described them as<br />

“doctors, lawyers, farmers, chemists,<br />

boys, students, and old men banded together.”<br />

The lookout sounded the alarm,<br />

and Menoyo ordered everyone to take up<br />

positions around the camp. The rebels<br />

were not to fire, Menoyo explained, unless<br />

he said so. Morgan crouched beside<br />

Menoyo, holding one of the few semiautomatic<br />

rifles. As the soldiers crept<br />

closer, a shot rang out.<br />

It was Morgan.<br />

Menoyo cursed under his breath as<br />

both sides began shooting. Bullets split<br />

trees in half, and a bitter-tasting fog of<br />

smoke drifted over the mountainside.<br />

The thunderous sounds of the guns made<br />

it nearly impossible to communicate. A<br />

Batista soldier was hit in the shoulder, a<br />

scarlet stain seeping through his uniform,<br />

and he tumbled down the mountain like<br />

a boulder. The commander of the Army<br />

patrol retrieved the wounded soldier and,<br />

along with the rest of his men, retreated<br />

into the wilderness, leaving a trail of<br />

blood.<br />

In the sudden quiet, Menoyo turned<br />

to Morgan and yelled, “Why the hell did<br />

you fire?”<br />

Morgan, when he was told in English<br />

what Menoyo was saying, seemed baffled.<br />

“I thought you said to shoot when I saw<br />

their eyes,” he said. No one had translated<br />

Menoyo’s original command.<br />

Morgan had made a mistake, but it<br />

had only hastened an inevitable battle.<br />

Menoyo told Morgan and the others to<br />

clear out: hundreds of Batista’s soldiers<br />

would soon be upon them.<br />

The men stuffed their belongings into<br />

backpacks made from sugar sacks.<br />

Menoyo took with him a medallion that<br />

his mother had given him, depicting the<br />

Immaculate Conception. Morgan tucked<br />

away his own mementos: photographs of<br />

a young boy and a young girl. The rebels<br />

divided into two groups, and Morgan set<br />

out with Menoyo and twenty others,<br />

marching for more than a hundred miles<br />

through the mountains.<br />

They usually moved during the night,<br />

then, at dawn, found a sheltered spot and<br />

ate what little food they had, taking turns<br />

sleeping while sentries kept watch. Morgan,<br />

who called one of his semi-automatic<br />

rifles his niño, always kept a weapon<br />

nearby. As darkness returned, the men<br />

resumed marching, listening to the

sounds of woodpeckers and barking dogs<br />

and their own exhausted breathing. Their<br />

bodies slackened from hunger, and beards<br />

covered their faces like jungle growth.<br />

When a nineteen-year-old rebel fell and<br />

broke his foot, Morgan supported him,<br />

making sure that he was not left behind.<br />

One morning during the march, a<br />

rebel was scrounging for food when he<br />

spotted about two hundred Batista soldiers<br />

in a nearby valley. The rebels faced<br />

annihilation. As panic spread, Morgan<br />

helped Menoyo devise a plan. They would<br />

prepare an ambush, hiding behind a series<br />

of large stones, in a U formation. It was<br />

critical, Morgan said, to leave an escape<br />

route. The rebels crouched behind the<br />

stones, feeling the warmth of the earth<br />

against their bodies, holding their rifles<br />

steady against their cheeks. Earlier, some<br />

of the young men had professed cheerful<br />

indifference to death, but their brio vanished<br />

as they confronted the prospect.<br />

Morgan braced himself for the fight.<br />

He had inserted himself into a foreign<br />

conflict, and now everything was at risk.<br />

His predicament was akin to that of Robert<br />

Jordan, the American protagonist of<br />

“For Whom the Bell Tolls,” who, while<br />

aiding the Republicans in the Spanish<br />

Civil War, must blow up a bridge: “He<br />

had only one thing to do and that was<br />

what he should think about....To worry<br />

was as bad as to be afraid. It simply made<br />

things more difficult.”<br />

Batista’s soldiers approached the ridge.<br />

Though the rebels could hear branches<br />

snapping under the soldiers’ boots,<br />

Menoyo told his men to hold fire, making<br />

sure that Morgan understood this<br />

time. Soon, the enemy soldiers were so<br />

close that Morgan could see the barrels of<br />

their guns. “Patria o Muerte,” Castro liked<br />

to say—“Fatherland or Death.” Finally,<br />

Menoyo gave the signal to shoot. Amid<br />

the screaming, blood, and chaos, some<br />

of the rebels fell back, but, as Shetterly<br />

wrote, “they noticed Morgan out in front<br />

of everyone, moving ahead, completely<br />

focused on the fight.”<br />

Batista’s soldiers started to flee.<br />

“They folded,” Armando Fleites, a<br />

medic with the rebels, recalls. “It was a<br />

complete victory.”<br />

More than a dozen of Batista’s soldiers<br />

were wounded or killed. The rebels, who<br />

took the dead soldiers’ guns, had not lost<br />

a single man, and afterward they enlisted<br />

Morgan to teach them better ways to<br />

“I wish my identity weren’t so wrapped up with who I am.”<br />

fight. One former rebel recalls, “He<br />

trained me in guerrilla warfare—how to<br />

handle different weapons, how to plant<br />

bombs.” Morgan instructed the men in<br />

judo and how to breathe underwater<br />

using a hollow reed. “There were so many<br />

things that he knew that we didn’t,” the<br />

rebel says. Morgan even knew some Japanese<br />

and German.<br />

He learned Spanish, becoming a full<br />

member of the group, which was dubbed<br />

the Second National Front of the Escambray.<br />

Like the other rebels, Morgan took<br />

an oath to “fight and defend with my life<br />

this little piece of free territory,” to “guard<br />

all the war secrets,” and to “denounce traitors.”<br />

Morgan rose quickly, first commanding<br />

half a dozen men, then leading<br />

a larger column and, finally, presiding<br />

over several square kilometres of occupied<br />

territory.<br />

As Morgan won more battles, the<br />

news of his curious presence began filtering<br />

out. A Cuban rebel radio station<br />

reported that rebels “led by an American”<br />

had killed forty Batista soldiers. Another<br />

broadcast hailed a “Yankee fighting for<br />

the liberty of Cuba.” The Miami newspaper<br />

Diario Las Américas stated that the<br />

American had been a “member of the<br />

‘Rangers’ who landed in Normandy and<br />

opened the way to the Allied forces by<br />

destroying the Nazi installations on the<br />

French coast before D Day.”<br />

• •<br />

U.S. and Cuban intelligence agents<br />

also began picking up chatter about a<br />

Yankee commando. In the summer of<br />

1958, the C.I.A. reported whispers of a<br />

rebel, “identified only as ‘El Americano,’”<br />

who had played a critical role in “planning<br />

and carrying out guerrilla activities,” and<br />

who had virtually wiped out a Batista unit<br />

while leading his men in an ambush. An<br />

informant from a Cuban revolutionary<br />

group told the F.B.I. that El Americano<br />

was Morgan. Another said that Morgan<br />

had “risked his life many times” to save<br />

the rebels, and was considered “quite a<br />

hero among these forces for bravery and<br />

daring.” The reports eventually set off a<br />

scramble among U.S. government agencies—including<br />

the C.I.A., the Secret<br />

Service, the State Department, Army intelligence,<br />

and the F.B.I.—to determine<br />

who William Alexander Morgan was,<br />

and whom he was working for.<br />

<strong>THE</strong> SECRET DOSSIER<br />

Edgar Hoover was feeling tremors of<br />

J. instability. First, there was his heart:<br />

in 1958, he had suffered a minor attack,<br />

at the age of sixty-three. The head of the<br />

F.B.I., Hoover was obsessed with his<br />

privacy, and kept the incident largely<br />

to himself, but he began a relentless<br />

diet-and-exercise regimen, disciplining<br />

his body with the same force of will that<br />

<strong>THE</strong> NEW YORKER, MAY 28, 2012 51

had eradicated a childhood stutter. He<br />

instructed the bureau’s research-andanalysis<br />

section to inform him of any<br />

scientific advancement that might extend<br />

the human life span.<br />

Compounding Hoover’s unease was<br />

that “infernal little Cuban republic,” as<br />

Theodore Roosevelt had described it.<br />

Hoover warned his agents that the growing<br />

number of Castro followers in the<br />

U.S. “may pose a threat to the internal security”<br />

of the country, and he had ordered<br />

his agents to infiltrate their organizations.<br />

Although Hoover rarely travelled<br />

abroad, he wanted to transform the F.B.I.<br />

into an international spy apparatus, building<br />

upon the vast network that he had<br />

created within the U.S., which trafficked<br />

in raw history: wiretapped conversations,<br />

surveillance photographs, papers from<br />

garbage bins, intercepted cables, gossip<br />

from ex-lovers.<br />

The U.S. intelligence branches had<br />

not yet turned up evidence that Castro<br />

or his followers were Communists, and,<br />

given Batista’s brutality, some American<br />

officials were developing a soft stance<br />

toward the rebels. The C.I.A. officer in<br />

charge of Caribbean operations later acknowledged,<br />

“My staff and I were all<br />

Fidelistas.”<br />

But Hoover remained vigilant: of all<br />

the enemies that he had hunted, he considered<br />

the agents of Communism the<br />

“Masters of Deceit,” as he called his 1958<br />

best-selling book about them. These<br />

plotters had hidden streams of information,<br />

and they mutated, like viruses, in<br />

order to slip past a host’s defenses; Hoover<br />

was determined to stop them from<br />

infiltrating an island just south of Florida.<br />

A source inside the U.S. Embassy in Havana<br />

had informed him that Batista’s<br />

hold on the country was “weakening.”<br />

Now Hoover was receiving reports of a<br />

wild gringo up in the mountains. Was<br />

Morgan a Soviet sleeper agent? A C.I.A.<br />

operative in a cover posture? Or one who<br />

had gone rogue?<br />

After peering into so many lives,<br />

Hoover understood that virtually everyone<br />

has secrets. Scribbled in a diary. Recorded<br />

on a cassette. Buried in a safe-deposit box.<br />

A secret may be, as Don DeLillo has written,<br />

“something vitalizing.” But it can also<br />

cut you down at any moment.<br />

By late 1958, Hoover had unleashed a<br />

team of G-men to figure out what Morgan<br />

might he hiding. One of them eventually<br />

knocked on the door of a large Colonial<br />

house in the Old West End of Toledo,<br />

Ohio. A distinguished-looking gentleman<br />

greeted him. It was Morgan’s father, Alexander,<br />

a retired budget director of a utility<br />

company and, as his son once described<br />

him, a “solid Republican.” He was married<br />

to a slim, devout woman, Loretta, who was<br />

known as Miss Cathedral, for her involvement<br />

in the Catholic church down the<br />

street. In addition to their son, they had a<br />

daughter, Carroll. Morgan’s father told the<br />

F.B.I. agent that he had not heard from his<br />

son, whom he called Bill, since he disappeared.<br />

But he provided a good deal of information<br />

about Morgan, and this, combined<br />

with F.B.I. interviews of other<br />

relatives and associates, helped Hoover and<br />

his spies piece together a startling profile of<br />

the Yankee rebel.<br />

Morgan should have been a quintessential<br />

American, a shining product<br />

of Midwestern values and a rising<br />

middle class. He attended Catholic<br />

school and initially earned high marks.<br />

(His I.Q. test showed “superior intelligence.”)<br />

He loved the outdoors and was a<br />

dedicated Boy Scout, receiving the organization’s<br />

highest award, in 1941. Years<br />

later, he wrote to his parents, “You . . .<br />

have done all that is possible to bring up<br />

your children with love of God and country.”<br />

Wildly energetic, he always seemed<br />

to be chattering, earning the nickname<br />

Gabby. “He was so likable,” his sister told<br />

me. “He could sell you anything.”<br />

But Morgan was also a misfit. He<br />

failed to make the football team, and his<br />

constant banter exposed a seam of insecurity.<br />

He disliked school and often<br />

slipped away to read stories of adventure,<br />

especially tales about King Arthur and<br />

the Knights of the Round Table, filling<br />

his mind with places far more exotic than<br />

the neighborhood of cropped lawns and<br />

boxy houses outside his bedroom window.<br />

His mother once said that Morgan<br />

had a “very, very vivid imagination,” and<br />

that he had brought his fancies to life,<br />

constructing, among other things, a “diving<br />

helmet” worthy of Jules Verne. He<br />

rarely showed “fear of anything,” and<br />

once had to be stopped from jumping off<br />

the roof with a homemade parachute.<br />

U.S. Army intelligence officials also<br />

investigated Morgan, preparing a dossier<br />

on him. (The dossier, along with hundreds<br />

of other declassified documents<br />

from the C.I.A., the F.B.I., the Army,<br />

and the State Department, was obtained<br />

through the Freedom of Information<br />

Act and through the National Archives.)<br />

In the Army’s psychological assessment,<br />

a military-intelligence analyst stated that<br />

the young Morgan “seemed to be fairly<br />

well adjusted to society.” But, by the<br />

time he was a teen-ager, his resistance to<br />

the strictures around him, and to those<br />

who wanted to pound him into shape,<br />

had reached a feverish state. As his<br />

mother put it, he had decided that, if he<br />

would never belong in Toledo, he would<br />

embrace exile, venturing “out in the<br />

world himself.”<br />

In the summer of 1943, at the age of<br />

fifteen, Morgan ran away. His mother<br />

later gave a report to the Red Cross about<br />

her son, saying, “Shocked is the mild word<br />

for it…for he had never done anything<br />

like this before.” Although Morgan returned<br />

home a few days later, he soon<br />

stole his father’s car and “took off” again,<br />

as he later put it, blowing through a red<br />

light before the police caught him. He<br />

was consigned to a detention center, but<br />

he slipped out a window and vanished<br />

again. He ended up in Chicago, where he<br />

joined the Ringling Brothers circus. Ten<br />

days later, his father found him taking<br />

care of the elephants, and brought him<br />

home.<br />

In the ninth grade, Morgan dropped<br />

out of school and began roaming the<br />

country, hopping buses and freighters; he<br />

earned money as a punch-press operator,<br />

a grocery clerk, a ranch hand, a coal<br />

loader, a movie-theatre usher, and a seaman<br />

in the Merchant Marine. His father<br />

seemed resigned to his son’s fitfulness,<br />

telling him in a letter, “Get as much adventure<br />

as you can and we will be glad to<br />

see you whenever you decide you want to<br />

come home.”<br />

Morgan later explained that he had<br />

not been unhappy at home—his parents<br />

had given him and his sister “anything<br />

that we wanted”—and had fled only because<br />

he longed “to see new places.”<br />

52 <strong>THE</strong> NEW YORKER, MAY 28, 2012

His mother believed that he had a<br />

mythic image of himself, and “always<br />

seemed to yearn to be a big shot,” but,<br />

given his “super affectionate nature,” she<br />

doubted that “he has really meant to<br />

worry or hurt us.”<br />

Nevertheless, Morgan increasingly<br />

took up with “the wrong kind of gangs of<br />

boys,” as he later called them, and got in<br />

scrapes with the law. While still a minor,<br />

he and some friends stole a stranger’s car,<br />

temporarily tying up the driver; he was<br />

also investigated for carrying a concealed<br />

weapon.<br />

Nobody—not his parents, not the<br />

F.B.I., not the military-intelligence analyst—could<br />

unravel the mystery of Morgan’s<br />

antisocial behavior; it remained forever<br />

encrypted, an unbreakable code. His<br />

mother wondered whether something<br />

had happened to him during her pregnancy,<br />

lamenting, “That boy hasn’t given<br />

me a moment’s peace....That’s why my<br />

hair is gray.” His father told the F.B.I.<br />

that perhaps his son needed to see one of<br />

those head doctors. A psychiatrist, cited<br />

by Army intelligence, speculated that<br />

Morgan was “driven along a course of<br />

self-destruction in order to satisfy his<br />

neurotic need for punishment.”<br />

Yet it was possible to see Morgan,<br />

with his brooding blue eyes and cigarette<br />

perpetually clamped between his teeth, as<br />

heralding a new social type: a beatnik, a<br />

rolling stone. A friend of Morgan’s once<br />

told a reporter, “Jack Kerouac was still<br />

imagining life on the road while Morgan<br />

was out there living it.”<br />

Morgan’s personality—“nomadic,<br />

egocentric, impulsive, and utterly irresponsible,”<br />

as Hoover’s agents put it—also<br />

had some similarities with that of a middle-class<br />

teen-ager thousands of miles<br />

away. In 1960, a conservative American<br />

journalist observed, “Like Fidel Castro,<br />

though on a lesser scale, Morgan was a superannuated<br />

juvenile delinquent.”<br />

Hoover and the F.B.I. discovered<br />

that, contrary to press accounts, Morgan<br />

had not served during the Second World<br />

War. Envisaging himself as a modern<br />

Sinbad—his other nickname—he had<br />

tried to enlist but was turned away, because<br />

he was too young. It was not until<br />

August, 1946, when the war was over and<br />

he was finally eighteen, that he joined<br />

the Army. After receiving orders that he<br />

would be deployed to Japan, in December,<br />

he cried in front of his mother for the<br />

first time in years, betraying that, despite<br />

his toughness, he was still just a teen-ager.<br />

He boarded a train for California, where<br />

he had a layover at a base, and on the way<br />

he sent his parents a telegram:<br />

Have surprise—married yesterday 12:30<br />

am to Darlene Edgerton. Am happy—will<br />

write or call soon as possible. Don’t worry or<br />

get excited.<br />

He had sat beside her on the train, in<br />

his starched uniform. “He was tall and<br />

handsome and so magnetic,” Edgerton,<br />

who is now eighty-seven and blind, recalls.<br />

“Truthfully, I was coming home to<br />

marry someone else, and we just hit it off<br />

and so we stopped off in Reno and got<br />

married.” They had known each other<br />

for only twenty-four hours and spent two<br />

days in a hotel before getting back on a<br />

train. When they reached California,<br />

Morgan reported to the base and left for<br />

Japan. “What young people will do,”<br />

Edgerton says.<br />

With Morgan stationed in Japan, the<br />

marriage dissolved after a year and a half,<br />

and Edgerton received an annulment—<br />

though even after she married another<br />

man she kept a letter from Morgan<br />

stashed away, which she occasionally<br />

unfolded, flattening the edges with her<br />

fingers, and read again, stirred by the<br />

memory of the comet-like figure who<br />

had briefly blazed into her life.<br />

“How come I never see that smile?”<br />

Morgan was crestfallen by the end of<br />

the relationship, but his mother told the<br />

Red Cross, “Knowing Bill, I am sure if he<br />

had an opportunity to date other girls he<br />

would soon forget this present love.”<br />

Indeed, Morgan took up with Setsuko<br />

Takeda, a German-Japanese<br />

night-club hostess in Kyoto, and got her<br />

pregnant. When Takeda was about to<br />

give birth to their son, in the fall of<br />

1947, he could not get a leave, and so he<br />

did what he had always done: he ran off.<br />

He was arrested for being AWOL, and,<br />

while in custody, he claimed that he<br />

needed to see Takeda—she was suicidally<br />

distraught after being harassed by<br />

another soldier. With the aid of a Chinese<br />

national who was also locked up,<br />

Morgan overpowered a military-police<br />

officer and stole his .45. “Morgan told<br />

me not to move,” the officer later<br />

testified. “He told me to take off my<br />

clothes. Then he told the Chinaman to<br />

tie me up.” Wearing the guard’s uniform<br />

and carrying his gun, Morgan escaped<br />

in the middle of the night.<br />

A military search party located<br />

Takeda, and she led authorities to a<br />

house where Morgan had said he would<br />

wait for her. When she saw Morgan in<br />

the rear of the building, she threw her<br />

arms around him. One of the officers,<br />

seeing the gun in his hand, screamed,

“Hey! It’s just Vlad being Vlad.”<br />

• •<br />

“Drop it!” Morgan hesitated, then, like a<br />

character in a dime novel, spun the pistol<br />

on his finger, so that the butt faced the<br />

officer, and handed it over. “It didn’t take<br />

you long to get here,” Morgan said, and<br />

asked for a cigarette.<br />

On January 15, 1948, at the age of<br />

nineteen, Morgan was sentenced by a<br />

court-martial to five years in prison. “I<br />

guess I got what was coming to me,” he<br />

said.<br />

His mother, in her statement to the<br />

Red Cross, pleaded for help: “I sincerely<br />

want him to be a boy that I can justly be<br />

proud of, not one to hang my head in<br />

shame for having given him birth.”<br />

Morgan was eventually transferred to<br />

a federal prison in Michigan. He enrolled<br />

in a class on American history;<br />

studied Japanese and German, the languages<br />

Takeda spoke; attended “religious<br />

instruction classes”; and sang in<br />

the church choir. In a progress report, a<br />

prison official wrote, “The Chaplain has<br />

noticed that inmate Morgan has developed<br />

a sense of social responsibility” and<br />

“is doing everything possible to improve<br />

himself and be an asset to society.”<br />

Morgan was released early, on April 11,<br />

1950. Though he had once hoped to reunite<br />

with Takeda and their son, the relationship<br />

had been severed. Morgan<br />

eventually moved to Florida, where he<br />

took a job in a carnival, as a fire swallower,<br />

and mastered the use of knives.<br />

He began a romance with the carnival’s<br />

snake charmer, Ellen May Bethel. A<br />

small, tempestuous woman with black<br />

hair and green eyes, she was “gorgeous,”<br />

a relative says. In the spring of 1955,<br />

Morgan and Bethel had a child, Anne.<br />

They were married several months later,<br />

and in 1957 they had a son, Bill.<br />

Morgan struggled to be an “asset to<br />

society,” but he seemed trapped by his<br />

past. He was an ex-con and a dishonorably<br />

discharged soldier—a stain that he<br />

tried, futilely, to expunge from his record.<br />

Morgan later told a friend that, during<br />

this period, “he was nothing.”<br />

According to an F.B.I. informant,<br />

Morgan went to work for the Mafia, running<br />

errands for Meyer Lansky, the diminutive<br />

Jewish gangster known as Little<br />

Man. In addition to overseeing rackets<br />

in the United States, Lanksy had become<br />

the kingpin of Havana, controlling many<br />

of its biggest casinos and night clubs. A<br />

Mob associate once described how Lansky<br />

“took Batista straight back to our<br />

hotel, opened the suitcases and pointed at<br />

the cash. Batista just stared at the money<br />

without saying a word. Then he and<br />

Meyer shook hands.”<br />

Morgan drifted back to the streets of<br />

Ohio, where he became associated with<br />

a local crime boss named Dominick Bartone.<br />

A gangster whose Mafia ties reputedly<br />

went back to the days of Al Capone,<br />

Bartone was a hulking man with thick<br />

black hair and dark eyes—a “typical<br />

hoodlum appearance,” according to his<br />

F.B.I. file. He classified people as either<br />

“solid” or “suckers.” His rap sheet eventually<br />

included convictions for bribery, gunrunning,<br />

tax evasion, and bank fraud,<br />

and he was closely allied with the head of<br />

the Teamsters, Jimmy Hoffa, whom he<br />

called “the greatest fella in the world.”<br />

One of Morgan’s friends from Ohio<br />

described him to me as “solid.” He said,<br />

“Do you know what ‘connection’ means?<br />

Well, Morgan was connected.” The friend,<br />

who said that he had been indicted for<br />

racketeering, suddenly grew quiet, then<br />

added, “I don’t know if you’re with the<br />

F.B.I. or the C.I.A.”<br />

Some members of the Mafia, including<br />

Bartone, prepared for shifting alliances<br />

in Cuba, shipping guns to the rebels.<br />

Morgan’s father thought that his son<br />

first got caught up in the whole Cuba<br />

business in 1955, in Florida, when he apparently<br />

met Castro, who had travelled<br />

there to garner support from the exile<br />

community for his upcoming invasion.<br />

Two years later, with Castro ensconced in<br />

the Sierra Maestra, Morgan left his wife<br />

and children in Toledo and began acquiring<br />

weapons across the U.S. and arranging<br />

for them to be smuggled to the rebels.<br />

Perhaps he was motivated by sympathy<br />

with the revolution, or by a desire to make<br />

money, or simply by an urge to flee domestic<br />

responsibilities. Morgan’s father<br />

told the F.B.I. that his son had run away<br />

“from his problems since he was a youngster,”<br />

and that his Cuban escapade was<br />

just another example. Morgan, who before<br />

heading to Havana had told another<br />

gunrunner that he would see him again in<br />

Florida “when this damn revolution is<br />

over,” later gave his own explanation: “I<br />

have lived always looking for something.”<br />

To this day, some scholars, and even<br />

some who knew Morgan, speculate that<br />

he was sent to the Escambray by the<br />

C.I.A. But, as declassified documents reveal,<br />

Hoover and his agents had discov-<br />

54 <strong>THE</strong> NEW YORKER, MAY 28, 2012

ered something more unsettling. Morgan<br />

was not working for the agency or a foreign<br />

intelligence outfit or the Mob. He<br />

was out there on his own.<br />

“C<br />

WHY AM I HERE<br />

alling Comandante William<br />

Morgan! Comandante William<br />

Morgan!”<br />

It was one of his men in the Escambray,<br />

speaking on shortwave radio.<br />

“Hear me!” came Morgan’s reply.<br />

“Send us reinforcements. We need<br />

help—ammunition! If we stay here, they<br />

will wipe us out.”<br />

By the summer of 1958, Morgan had<br />

endured countless skirmishes. “We were<br />

always outnumbered at least thirty to<br />

one,” Morgan recalled. “We were a small<br />

outfit, but we were mobile and hard-hitting.<br />

We became known as the phantoms<br />

of the mountains.”<br />

Morgan had witnessed, up close, the<br />

cruelties of the Cuban regime: villages<br />

ransacked and burned by Batista’s Army,<br />

friends shot in the head, a senile man’s<br />

tongue cut out. “I know and have seen<br />

what these people have been doing,”<br />

Morgan said of Batista’s henchmen.<br />

“They killed. They tortured. They beat<br />

people...and done things that don’t have<br />

a name.”<br />

On one of his uniform sleeves, Morgan<br />

had sewn a U.S. flag. “I was born an<br />

American,” he liked to say.<br />

At night, he often sat by the campfire,<br />

where scattered sparks created fleeting<br />

constellations, and listened to the rebels<br />

share their visions of the revolution. The<br />

movement’s various factions—including<br />

two other groups in the Escambray and<br />

Castro’s forces in the Sierra Maestra—<br />

represented an array of ideologies and<br />

personal ambitions. The Escambray front<br />

advocated a Western-style democracy<br />

and was staunchly anti-Communist, a<br />

stance that was apparently shared by<br />

Fidel Castro, who, unlike his brother<br />

Raúl or Che Guevara, had expressed little<br />

interest in Marxism-Leninism. In the<br />

Sierra Maestra, Castro told a reporter, “I<br />

have never been, nor am I now, a Communist.<br />

If I were, I would have sufficient<br />

courage to proclaim it.”<br />

In the Escambray, Morgan and<br />

Menoyo had grown increasingly close.<br />

Morgan was older, and almost suicidally<br />

brave, like the brother of Menoyo’s who<br />

had died in the Batista raid. Morgan addressed<br />

Menoyo as “mi jefe y mi hermano”—“my<br />

chief and my brother”—and<br />

told him about his troubled past. Menoyo<br />

felt that Morgan was maturing, as a soldier<br />

and a man. “Little by little, William<br />

was changing,” Menoyo says.<br />

In July, after Morgan was promoted to<br />

comandante, he wrote a letter to his<br />

mother, something that he had not done<br />

during his six months in the mountains.<br />

Written with a distinctive flourish of<br />

dashes, it said, “I know that you neither<br />

approve or understand why I am here—<br />

even though you are the one person in the<br />

world—that I believe understands me—I<br />

have been many places—in my life and<br />

done many things of which you did not<br />

approve—or understand, nor did I understand<br />

myself—at the time.”<br />

He contended with his old sins, acknowledging<br />

how much pain he had<br />

caused Ellen, his second wife, and their<br />

children (“these three who I have hurt<br />

deeply”) by abandoning them. “It is hard<br />

to understand but I love them very deeply<br />

and think of them often,” he wrote. Ellen<br />

had filed for divorce, on the ground of desertion.<br />

“I don’t expect she has much faith<br />

or love for me any more,” Morgan wrote.<br />

“And probably she is right.”<br />

Yet he wanted his mother to understand<br />

that he was no longer the same<br />

person. “I am here with men and boys—<br />

who fight for . . . freedom,” he wrote.<br />

“And if it should happen that I am<br />

killed here—You will know it was not<br />

for foolish fancy—or as dad would say a<br />

pipe dream.” The friend who had also<br />

smuggled weapons to the rebels later<br />

told the Palm Beach Post, “He had<br />

found his cause in Cuba. He wanted<br />

something to believe in. He wanted to<br />

have a purpose. He wanted to be someone,<br />

not no one.”<br />

Morgan had composed a more philosophical<br />

statement about why he had<br />

joined the rebels. The essay, titled “Why<br />

Am I Here,” said:<br />

Why do I fight here in this land so foreign<br />

to my own? Why did I come here far from<br />

my home and family? Why do I worry about<br />

these men here in the mountains with me? Is<br />

it because they were all close friends of mine?<br />

No! When I came here they were strangers to<br />

me I could not speak their language or understand<br />

their problems. Is it because I seek<br />

adventure? No here there is no adventure<br />

only the ever existent problems of survive. So<br />

why am I here? I am here because I believe<br />

that the most important thing for free men to<br />

do is to protect the freedom of others. I am<br />

here so that my son when he is grown will<br />

not have to fight or die in a land not his own,<br />

because one man or group of men try to take<br />

his liberty from him I am here because I believe<br />

that free men should take up arms and<br />

stand together and fight and destroy the<br />

groups and forces that want to take the<br />

rights of people away.<br />

In his rush to overturn Cuba’s past as<br />

well as his own, Morgan often forgot to<br />

pause for periods or paragraph breaks.<br />

He acknowledged, “I can not say I have<br />

always been a good citizen.” But he explained<br />

that “being here I can appreciate<br />

the way of life that is ours from<br />

birth,” and he recounted the seemingly<br />

impossible things that he had seen:<br />

“Where a boy of nineteen can march 12<br />

hours with a broken foot over country<br />

comparable to the american Rockies<br />

without complaint. Where a cigarette is<br />

smoked by ten men. Where men do<br />

without water so that others may<br />

drink.” Noting that U.S. policies had<br />

propped up Batista, he concluded, “I<br />

ask myself why do we support those<br />

who would destroy in other lands the<br />

ideals which we hold so dear?”<br />

Morgan sent the statement to someone<br />

he was sure would sympathize with<br />

it: Herbert Matthews. The Times reporter<br />

considered Morgan to be “the<br />

most interesting figure in the Sierra de<br />

Escambray.” Soon after receiving the<br />

statement, Matthews published an article<br />

about the Second Front and its “tough,<br />

uneducated young American” leader, citing<br />

a cleaned-up passage from Morgan’s<br />

letter.<br />

Other U.S. newspapers began chronicling<br />

the exploits of the “adventurous<br />

American,” the “swashbuckling Morgan.”<br />

The Washington Post reported<br />

that he had become a “daring fellow” by<br />

the age of three. The accounts were<br />

enough to “make schoolboys drool,” as<br />

one newspaper put it. A retired businessman<br />

from Ohio later told the Toledo<br />

Blade, “He was like a cowboy in an<br />

Ernest Hemingway adventure.” Morgan<br />

had finally willed his interior fictions<br />

into reality.<br />

One day in the spring of 1958, while<br />

Morgan was visiting a guerrilla<br />

camp for a meeting of the Second Front’s<br />

chiefs of staff, he encountered a rebel<br />

he had never seen before: small and slender,<br />

with a face shielded by a cap. Only up<br />

close was it evident that the rebel was a<br />

<strong>THE</strong> NEW YORKER, MAY 28, 2012 55

woman. She was in her early twenties,<br />

with dark eyes and tawny skin, and, to<br />

conceal her identity, she had cut her curly<br />

light-brown hair short and dyed it black.<br />

Though she had a delicate beauty, she<br />

locked and loaded a gun with the ease<br />

of a bank robber. Morgan later said of a<br />

pistol that she carried, “She knows how<br />

to use it.”<br />

Her name was Olga Rodríguez. She<br />

came from a peasant family, in the central<br />

province of Santa Clara, that often<br />

went without food. “We were so poor,”<br />

Rodríguez recalls. She studied diligently,<br />

and was elected class president.<br />

Her goal was to become a teacher. She<br />

was bright, stubborn, and questioning—<br />

as Rodríguez puts it, “always a little<br />

different.” Increasingly angered by the<br />

Batista regime’s repressiveness, she<br />

joined the underground resistance, organizing<br />

protests and assembling bombs<br />

until, one day, agents from Batista’s secret<br />

police appeared in her neighborhood,<br />

showing people her photograph.<br />

“They were coming to kill me,” Rodríguez<br />

recalls.<br />

When the secret police could not find<br />

her, they beat up her brother, heaving<br />

him on her parents’ doorstep “like a sack<br />

of potatoes,” she says. Her friends begged<br />

her to leave Cuba, but she told them, “I<br />

will not abandon my country.” In April,<br />

1958, with her appearance disguised and<br />

with a tiny .32 pistol tucked in her underwear,<br />

she became the first woman to join<br />

the rebels in the Escambray. She tended<br />

to the wounded and taught rebels to read<br />

and write. “I have the spirit of a revolutionary,”<br />

she liked to say.<br />

When Morgan met her, he gently<br />

teased her about her haircut, pulling<br />

down her cap and saying, “Hey, muchacho.”<br />

Morgan had arrived at the camp<br />

literally riding a white horse, and she<br />

had felt her heart go “boom, boom,<br />

boom.”<br />

“I am a great romantic, and I was so<br />

moved that someone from another<br />

country would care enough about my<br />

countrymen to fight for them,” she says.<br />

Morgan repeatedly sought her out at her<br />

camp. She would sometimes prepare<br />

him rice and beans (“I’m a guerrilla, not<br />

a cook”), and he would complain, “Too<br />

fast!” as she spoke, in gunfire-patter<br />

Spanish, about the need to hold elections<br />

and build hospitals and schools. She<br />

seemed unlike so many of the women<br />

whom he had impetuously taken up<br />

with. Like his mother, she had a deep<br />

sense of conviction, and it was her<br />

influence, Menoyo says, that furthered<br />

“William’s transformation,” though<br />

Rodríguez saw it differently: Morgan<br />

was not so much changing as discovering<br />

who he really was. “I knew William had<br />

not always been a saint,” Rodríguez says.<br />

“But inside, I could tell, he had a huge<br />

heart—one that he had opened not just<br />

to me but to my country.”<br />

Morgan recognized the risk of surrendering<br />

to a flight of emotion in the midst<br />

of war. The Batista regime had placed<br />

a twenty-thousand-dollar bounty on<br />

him—“dead or alive,” as Morgan put it.<br />

Once, when Morgan and Rodríguez<br />

were together, a military plane shut down<br />

its engines, so that they could not hear its<br />

approach until bombs were falling upon<br />

them. “We simply had to dive for cover,”<br />

Rodríguez recalls. They barely escaped<br />

unharmed. During other bombing raids,<br />

they would hold each other, whispering,<br />

“Our fates are intertwined.”<br />

When Robert Jordan is overcome<br />

with love for a woman during the Spanish<br />

Civil War, he fears that they will never<br />

experience what ordinary people do: “Not<br />

time, not happiness, not fun, not children,<br />

not a house, not a bathroom, not a<br />

clean pair of pajamas, not the morning<br />

paper, not to wake up together, not to<br />

wake and know she’s there and that you’re<br />

not alone. No. None of that.”<br />

As long as Morgan was fighting in the<br />

Escambray, there could be no past or future—only<br />

the present. “We could never<br />

have peace,” Rodríguez says. “From the<br />

beginning, I had this terrible feeling that<br />

things would not end well.” Yet the impossibility<br />

of their romance only deepened<br />

their ardor. Not long after they met,<br />

a boy from a nearby village approached<br />

Rodríguez in camp, carrying a bunch of<br />

purple wildflowers. “Look what the<br />

Americano has sent you,” the boy told her.<br />

A few days later, the boy appeared again,<br />

holding a new bouquet. “From the Americano,”<br />

he said.<br />

As Morgan later told her, they had to<br />

“steal time.” In one such moment, a photographer<br />

caught them standing in a<br />

mountain clearing. In the image, both are<br />

wearing fatigues; a rifle is slung over his<br />

right shoulder, and she leans on one, as if<br />

it were a cane. With their free hands, they<br />

are clutching each other. “When I found<br />

you, I found everything I can wish for in<br />

the world,” he later wrote her. “Only<br />

death can separate us.”<br />

ORGAN WAS KILLED <strong>THE</strong> PREVI-<br />

“M OUS NIGHT IN <strong>THE</strong> COURSE OF A<br />

FIGHT WITH <strong>THE</strong> CUBAN ARMY.” So<br />

read an urgent cable sent from the U.S.<br />

Embassy in Havana to Hoover, at F.B.I.<br />

headquarters, on September 19, 1958.<br />

The Batista regime, which had already<br />

leaked the news to the Cuban press,<br />

mailed the F.B.I. two photographs of a<br />

fractured corpse, shirtless and smeared<br />

with blood.<br />

Morgan’s mother was devastated when<br />

she heard of the reports. Several weeks<br />

later, she received a letter from Cuba, in<br />

Morgan’s hand. It said, “The Cuban press<br />

last month sent out word that I was dead<br />

but as you can tell I am not.”<br />

Just as Batista’s regime had falsely declared<br />

Castro’s death, it had made the<br />

mistake of believing its own propaganda<br />

about Morgan, becoming trapped in the<br />

closed circuit of information that isolates<br />

tyrants not only from their countrymen<br />

but from reality. Meanwhile, Morgan’s<br />

seeming emergence from the dead, like<br />

one of Mulholland’s magical feats, created<br />

a potent counter-illusion: that he<br />

was indestructible.<br />

In October, Che Guevara arrived<br />

in the Escambray, with a hundred or<br />

so ghostly-looking soldiers. They had<br />

completed a six-week westward trek from<br />

the Sierra Maestra, withstanding cyclones<br />

and enemy fire and sleeping in<br />

swamps. Guevara described his men as<br />

“morally broken, starving...their feet<br />

bloodied and so swollen they won’t fit<br />

into what’s left of their boots.” Guevara—<br />

whom another rebel once depicted as<br />

“half athletic and half asthmatic,” and<br />

prone to shifting in conversation “between<br />

Stalin and Baudelaire”—had dark<br />

hair nearly to his shoulders. During the<br />

march, he had worn the cap of a dead<br />

comrade, but, to his distress, he had lost<br />

it, and so he began wearing a black beret.<br />

The ranks of the Second Front had<br />

grown to more than a thousand men.<br />

Morgan wrote to his mother, “We are<br />

much stronger now,” and said that his<br />

men were “getting ready to come down<br />

from the hills and take the cities.”<br />

Guevara had been sent to the Escambray<br />

to take control of the Second Front,<br />

56 <strong>THE</strong> NEW YORKER, MAY 28, 2012

COURTESY OLGA MORGAN GOODWIN<br />

Morgan and Olga Rodríguez, in 1958. Their relationship, she says, was “un gran amor.”<br />

as Castro was eager to eliminate any<br />

threat to his dominance and to accelerate<br />

the assault on Batista. But many rebels<br />

there resisted having their authority<br />

usurped, and submerged tensions between<br />

the groups rose to the surface.<br />

When Guevara and his men tried to enter<br />

a stretch of territory, they were confronted<br />

by a particularly combative leader of the<br />

Second Front, Jesús Carreras. After demanding<br />

a password from Guevara, Carreras<br />

refused to let him or his men pass.<br />

Morgan and Guevara, the two foreign<br />

comandantes, bitterly distrusted each<br />

other. The boisterous, fun-loving, anti-<br />

Communist American had little in common<br />

with the ascetic, erudite, Marxist-<br />

Leninist Argentine doctor. Morgan<br />

complained to Guevara that he had misappropriated<br />

weapons belonging to the<br />

Second Front, while Guevara dismissed<br />

Morgan and his defiant guerrillas as<br />

comevacas—“cow-eaters”—meaning that<br />

they sat around and lived off the largesse<br />

of peasants. Although Guevara and the<br />

Second Front reached an “operational<br />

pact,” friction remained.<br />

In November, 1958, before a climactic<br />

push against Batista’s Army, Morgan<br />

slipped away with Rodríguez to a farmhouse<br />

in the mountains, where they arranged<br />

to get married. They wore their<br />

rebel uniforms, which they had washed in<br />

the river. They didn’t have rings, so Morgan<br />

took a leaf from a tree, rolled it into a<br />

circle, and placed it on her finger, vowing,<br />

“I will love you and honor you all the days<br />

of my life.” Rodríguez said, “Hasta que la<br />

muerte nos separe”—“Till death do us part.”<br />

After the ceremony, Morgan picked<br />

up his gun and returned to battle. “We<br />

barely had time to kiss,” Rodríguez recalls.<br />

As the fighting intensified, she had<br />

a growing sense of unease. To keep her<br />

company, he had given her a parrot that<br />

cried “We-liam” and “I love you!” But one<br />

day it flew off, and never returned.<br />

In late December, Guevara and his<br />

party launched a ferocious assault in the<br />

Santa Clara province, winning a decisive<br />

victory. That month, Morgan and the<br />

Second Front seized the tobacco town of<br />

Manicaragua, then pressed onward, capturing<br />

Cumanayagua, El Hoyo, La<br />

Moza, and San Juan de los Yeras, before<br />

reaching Topes de Collantes, a hundred<br />

and sixty miles southeast of Havana.<br />

One of Batista’s colonels warned,<br />

“Headquarters can’t resist anymore. The<br />

Army doesn’t want to fight.” The Second<br />

Front had earlier issued a statement<br />

declaring that “the dictatorship is nearly<br />

crushed,” and the U.S. government tried<br />

to push out Batista, in a futile attempt to<br />

install an acquiescent “third force.” Batista<br />

resisted the Americans’ pressure,<br />

but his hold on power was nearly gone.<br />

At 4 A.M. on New Year’s Day, David<br />

Atlee Phillips, a C.I.A. agent stationed in<br />

Havana, was standing outside his home<br />

there, drinking champagne, when he<br />

looked up and saw a speck of light—an<br />

airplane—receding into the sky. Realizing<br />

that there were no departing flights at<br />

that hour, he telephoned his case officer,<br />

and offered a gem of information: “Batista<br />

just flew into exile.”<br />

“Are you drunk?” the case officer<br />

replied.<br />

But Phillips was right—Batista was<br />

escaping, with his entourage, to the Dominican<br />

Republic—and word rapidly<br />

spread throughout Cuba: “Se fue! Se fue! ”<br />

He’s gone!<br />

Meyer Lansky was in Havana at the<br />

time, and was among the first people<br />

there to be tipped off. “Get the money,”<br />

he commanded an associate. “All of it.<br />

Even the cash and checks in reserve.”<br />

After dawn, Morgan was preparing to<br />

battle for the city of Cienfuegos when the<br />

cry reached him and Rodríguez: Se fue! Se<br />

fue! Morgan ordered his men to take the<br />

city immediately. Everyone, including<br />

Rodríguez, jumped into cars and trucks,<br />

racing into a city where they had expected<br />

an intense battle but where Batista’s<br />

Army, once impregnable, dissolved before<br />

them as thousands of jubilant residents<br />

poured into the streets, honking<br />

horns and banging on makeshift drums.<br />

The crowds greeted Morgan, who<br />

wrapped a rebel flag around his shoulders<br />

<strong>THE</strong> NEW YORKER, MAY 28, 2012 57

like a cape, to shouts of “Americano!”<br />

Morgan, who told reporters, “I’m forgetting<br />

my English,” cried at the crowds<br />

grasping at him, “Victoria! Libertad!”<br />

In an interview with Look, Morgan<br />

said, “When we came down from the<br />

mountains, it was a shock to all of<br />

us...to find how much faith the Cuban<br />

people had in this revolution. You felt<br />

you simply couldn’t betray their hopes.”<br />

Morgan was put in charge of Cienfuegos.<br />

He had finally become somebody,<br />

he told a friend. On January 6, 1959, at<br />

one in the morning, Castro paused in<br />

Cienfuegos during his triumphant march<br />

to Havana. It was the first time that Morgan<br />

had met with Castro in Cuba, and<br />

the two former delinquents shook hands<br />

and congratulated each other.<br />

In interviews, Castro repeated his opposition<br />

to Communism and promised<br />

to hold elections within eighteen months.<br />

Before a gathering of thousands in Havana,<br />

he vowed, “We cannot become dictators.”<br />

Whatever doubts Morgan had<br />

about Guevara, he seemed to harbor<br />

none about Castro, who once declared,<br />

“History will absolve me.”<br />

“I have a tremendous admiration—a<br />

tremendous respect—for the man,” Morgan<br />

later told the American television<br />

broadcaster Clete Roberts. “I respect his<br />

moral courage, and I respect his honesty.”<br />

Morgan cast the revolution in his own<br />

distinctive terms: “It’s about time the little<br />

guy got a break.”<br />

Roberts observed that Morgan’s life,<br />

including his romance with Rodríguez,<br />

sounded “like all of the movie scripts that<br />

were ever dreamt about in Hollywood.”<br />

Morgan insisted that he had no interest<br />

in selling his story: “I don’t believe that<br />

you should cash in on your ideals. I don’t<br />

believe I was an idealist when I went up<br />

into the mountains, but I feel that I’m an<br />

idealist now.”<br />

Morgan had not slept for two days<br />

after Batista fled, and he welcomed the<br />

chance to shave and wash the jungle<br />

grime off his body. Rodríguez soon<br />

changed out of her uniform, confident<br />

that “the war was over and that we would<br />

raise a family and live in a democracy.” In<br />

Cienfuegos, they exchanged proper wedding<br />

rings. Rodríguez says, “I cannot describe<br />

the happiness I felt—we felt.”<br />

Rodríguez had become pregnant. For<br />

Morgan, it suddenly seemed that he and<br />

Rodríguez could have everything: a house,<br />

children, the morning paper. As Morgan<br />

put it, “All I’m interested in is settling<br />

down to a nice, peaceful existence.”<br />

<strong>THE</strong> CONSPIRACY<br />

In March, 1959, a mysterious American<br />

suddenly appeared at the Hotel Capri,<br />

where Morgan and Rodríguez were staying<br />

temporarily. The man, who was in his<br />

late forties, had stiff black hair and thick<br />

glasses, and looked like he could be an<br />

employee of NASA, the new space agency.<br />

“I still say we pull it and deal with the consequences<br />

of its being a false alarm when they come.”<br />

In the lobby, he called Morgan and said<br />

that he needed to see him. His name was<br />

Leo Cherne. “I’m sure he never heard of<br />

me before,” Cherne recalled, in an unpublished<br />

oral history.<br />

Imposing, learned, and discreet,<br />

Cherne was a wealthy businessman and a<br />

power broker who had advised several<br />

U.S. Presidents, including Franklin<br />

Roosevelt and Eisenhower. In 1951, he<br />

became chairman of the International<br />

Rescue Committee. Over the years, there<br />

was speculation that, under Cherne, the<br />

I.R.C. had sometimes served as a front<br />

for C.I.A. activities—a charge that<br />

Cherne publicly denied. In any case, he<br />

was enmeshed with people in intelligence<br />

circles, a man who relished being privy to<br />

a cloak-and-dagger world.<br />

In his oral history, Cherne said that he<br />

had once been “deeply attracted” to Castro,<br />

rivalling Herbert Matthews in his<br />

“blind enthusiasm.” But Cherne had<br />