PLUNDERING PALESTINE - Jerusalem Quarterly

PLUNDERING PALESTINE - Jerusalem Quarterly

PLUNDERING PALESTINE - Jerusalem Quarterly

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

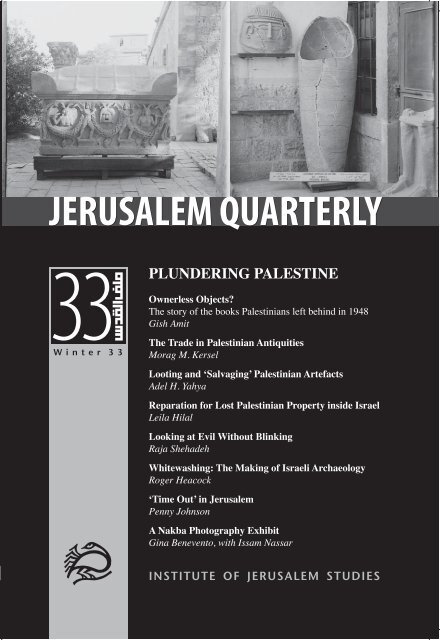

<strong>PLUNDERING</strong> <strong>PALESTINE</strong><br />

Ownerless Objects?<br />

The story of the books Palestinians left behind in 1948<br />

Gish Amit<br />

Winter 33<br />

The Trade in Palestinian Antiquities<br />

Morag M. Kersel<br />

Looting and ‘Salvaging’ Palestinian Artefacts<br />

Adel H. Yahya<br />

Reparation for Lost Palestinian Property inside Israel<br />

Leila Hilal<br />

Looking at Evil Without Blinking<br />

Raja Shehadeh<br />

Whitewashing: The Making of Israeli Archaeology<br />

Roger Heacock<br />

‘Time Out’ in <strong>Jerusalem</strong><br />

Penny Johnson<br />

A Nakba Photography Exhibit<br />

Gina Benevento, with Issam Nassar<br />

INSTITUTE OF JERUSALEM STUDIES

Issue القدس — 29 — 2008 Summer Winter 2007<br />

33 ملف<br />

formerly the <strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> File<br />

Local Newsstand Price: 14 NIS<br />

Local Subscription Rates<br />

Individual - 1 year: 50 NIS<br />

Institution - 1 year: 70 NIS<br />

International Subscription Rates<br />

Individual - 1 year: USD 25<br />

Institution - 1 year: USD 50<br />

Students - 1 year: USD 20<br />

(enclose copy of student ID)<br />

Single Issue: USD 5<br />

For local subscription to JQ, send a check or money order to:<br />

The Institute of <strong>Jerusalem</strong> Studies<br />

P.O. Box 54769, <strong>Jerusalem</strong> 91457<br />

Tel: 972 2 298 9108, Fax: 972 2 295 0767<br />

E-mail: jqf@palestine-studies.org<br />

For international or US subscriptions send a check<br />

or money order to:<br />

The Institute for Palestine Studies<br />

3501 M Street, N.W.<br />

Washington, DC 20007<br />

Or subscribe by credit card at the IPS website:<br />

http://www.palestine-studies.org<br />

The publication is also available at the IJS website:<br />

http://www.jerusalemquarterly.org<br />

(Please note that we have changed our internet address<br />

from www.jqf-jerusalem.org.)<br />

Institute of <strong>Jerusalem</strong> Studies

Table of Contents<br />

EDITORIAL<br />

Why Are Those Men in Black Camping Near the Wall? .......................................3<br />

FEATURES<br />

Ownerless Objects?....................................................................................................7<br />

The story of the books Palestinians left behind in 1948<br />

Gish Amit<br />

The Trade in Palestinian Antiquities......................................................................21<br />

Morag M. Kersel<br />

Looting and ‘Salvaging’...........................................................................................39<br />

How the Wall, illegal digging and<br />

the antiquities trade are ravaging Palestinian cultural heritage<br />

Adel H. Yahya<br />

Reparation for Lost Palestinian Property inside Israel........................................56<br />

A review of international developments<br />

Leila Hilal<br />

REVIEWS<br />

Looking at Evil Without Blinking...........................................................................65<br />

A review of Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine<br />

Raja Shehadeh<br />

Whitewashing: ‘Everybody’ Does It.......................................................................... 71<br />

A review of Raz Kletter, Just Past? The Making of Israeli Archaeology<br />

Roger Heacock<br />

‘Time Out’ in <strong>Jerusalem</strong>..........................................................................................76<br />

Penny Johnson<br />

‘I Come From There and Remember’....................................................................80<br />

A coming photography exhibit commemorating the Nakba<br />

Gina Benevento, with Issam Nassar<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> Diary................................................................................................83<br />

December 2007 – March 2008<br />

Cover photos: Two images of objects in the (former) Palestine Archaeological Museum by<br />

photographer Eric Matson in the late British Mandate period. Source: Library of Congress

Why Are Those<br />

Men in Black<br />

Camping Near<br />

the Wall?<br />

An Israeli ‘archeological dig’ along the path<br />

of the wall in al-Jib in the West Bank. Al-Jib<br />

is the site of 7 th -8 th century wine cellars<br />

and has been identified as the Biblical<br />

‘Gibeon’ through Hebrew inscriptions found<br />

by James Pritchard in 1956. The modern<br />

village is home to some 5,000 Palestinians<br />

who will be encircled by the wall Israel is<br />

building through the West Bank.<br />

Photo credit: Adel Yaha/PACE<br />

Two colleagues on an early autumn walk<br />

near Bir Nabala, a <strong>Jerusalem</strong>-area village<br />

now cut off from <strong>Jerusalem</strong> by the Wall<br />

Israel is constructing through the West<br />

Bank, asked themselves this question and<br />

wondered whether to investigate. Despite<br />

the looming presence of the Wall, their<br />

walk had been pleasant. A Palestinian man<br />

tending his orchard had provided a bag of<br />

pomegranates; workers at a stone quarry<br />

invited them for tea and told stories of their<br />

problems of living in Hebron and working<br />

near Ramallah–the ‘absence of movement’<br />

tales that often dominate Palestinian<br />

interchange.<br />

Our colleagues, a sociologist and an<br />

anthropologist, always have their<br />

investigative antenna out, so the Men in<br />

Black had likewise to be interrogated.<br />

They were forthcoming but the information<br />

they gave was disturbing: they announced<br />

themselves Druze police attached to the<br />

Israeli army and charged with guarding a<br />

temporary archaeological ‘dig’ along the<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 3 ]

course of the Wall. “It’s all ours,” they explained, waving their hands over the land and<br />

what lay beneath it. 1<br />

When the Men in Black declared “It’s all ours,” they were in violation of international<br />

law (particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention) but nonetheless operating within the<br />

bounds of a certain kind of Israeli legality. In an important new book, Eyal Weizman<br />

points out that “on the same day that Arab <strong>Jerusalem</strong> and the area around it was<br />

annexed to Israel, the Israeli government declared the archaeological and historical<br />

sites in the West Bank, primarily those of Jewish or Israelite cultural relevance, to be<br />

the state’s ‘national and cultural property’, amounting to de facto annexation of the<br />

ground beneath the Occupied Territories, making it the first zone to be colonized.” 2<br />

The manner in which Israeli law undergirds illegal activity in this colonized zone–and<br />

the destruction of the non-renewable resource of the cultural heritage of Palestine–<br />

concerns a number of authors in this special issue of <strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong>. New<br />

opportunities for archaeological looting provided by the construction of the Wall are<br />

carried out by agents of the Israeli state, and accompany the “matrix of control” (Jeff<br />

Halper’s phrase) represented by the Wall. Similarly, the construction of Road 6, whose<br />

north-south course also produces more annexation of West Bank land, was accompanied<br />

by Israeli ‘salvage archaeology’ that yielded a range of “material objects…sherds and<br />

ceramics and an extensive cemetery…variously attributed to periods ranging from the<br />

Iron Age, Persian, Hellenistic and Early Roman to late Byzantine.” 3<br />

In his article in this volume, Adel Yahya notes that about 1,500 archaeological sites are<br />

isolated between the Wall (in its western course) and the Green Line, including over<br />

250 ‘high potential’ sites–a tempting array indeed for Israel’s ‘salvage’ operations.<br />

These state operations are joined on the other side of the Wall by what Adel Yahya<br />

calls Palestinian ‘subsistence looters’, driven by poverty and enabled by the lack<br />

of Palestinian security and enforcement. Palestinians “looting in their backyard”<br />

are integrated into Israel’s ‘legal’ market of antiquities, where Yahya estimates they<br />

receive perhaps 1% of the value of the objects they offer.<br />

Like Morag Kersel in this volume, Yahya opposes the legal trade in antiquities–both<br />

in Israel and Palestine–as a course that leads both to illegal looting and the destruction<br />

of a cultural heritage that belongs to all. Kersel offers a carefully-considered review of<br />

“the historical antecedents, the current practice, and the future initiatives” of cultural<br />

heritage law and the trade in antiquities, including Ottoman, Mandate and current<br />

Israeli legislation. While noting the inequities in the interim (Oslo) agreements,<br />

where Palestine is obligated to safeguard archaeological sites but there is no Israeli<br />

reciprocity, Kersel examines the Palestinian Draft Cultural and Natural Heritage Law<br />

2003 and cautions that confirming a legal trade in antiquities may further endanger a<br />

heritage already in peril. The <strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> would welcome interventions on<br />

this critical question from its readers.<br />

[ 4 ] EDITORIAL Why are Those Men in Black Camping Near the Wall?

The looting and loss of Palestinian cultural and other property in 1948 is examined<br />

in several contributions to this volume. In an illuminating piece, Gish Amit relates<br />

the ‘untold story’ of the fate of Palestinian libraries and books ‘abandoned’ in 1948<br />

(and their depository in Israel’s national library), making the important point that<br />

“occupation and colonization does not end in taking over physical space. They achieve<br />

their fulfillment by occupying cultural space as well, and by turning the cultural<br />

artefacts of the victims into ownerless objects with no past.” Amit implicitly raises<br />

an important question that has not been fully addressed by concerned Palestinians:<br />

how to re-claim these objects, not simply physically as property, but also culturally<br />

as embodiments of patrimony. In a helpful review of the right of Palestinians to<br />

reparations for lost property inside Israel, legal expert Leila Hilal points out that<br />

“the fate of Palestinian properties inside Israel has often times been neglected for<br />

the issue of the right of return,” but that the right of return and restitution are in fact,<br />

independent rights and that therefore, delving into issues of restitution does not forgo<br />

the right of return.<br />

Reviews of two books address new scholarship on the 1948 war and its aftermath,<br />

as well as the destruction of cultural and other property. Raja Shehadeh reviews Ilan<br />

Pappe’s crucial new investigation of Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Palestinians in 1948,<br />

while Roger Heacock critiques the uneasy mixture of revelation and justification<br />

in Raz Ketter’s Just Past? The Making of Israeli Archaeology. Ketter, a long-time<br />

employee of the Israeli Antiquities Authority (IAA), uses IAA archives to document<br />

the Israeli army’s vast swath of destruction of archaeological, historical and other<br />

cultural sites not only during the 1948 war but for years afterwards, while largely<br />

defending the role of the IAA itself. Aside from the historical evidence, the recent<br />

approval of the IAA to allow construction of a Museum of Tolerance on the site of an<br />

ancient Muslim cemetery in <strong>Jerusalem</strong>’s Mamilla district raises questions about how<br />

professionalism and commitment to preservation of cultural heritage operates in that<br />

state institution.<br />

A scholar who offered an alternative, pioneering and carefully-researched view of the<br />

history and role of Israeli archaeology in her 2001 book 4 –Barnard professor Nadia<br />

Abu El-Haj–was subjected last year not to an academic critique, but to a right-wing<br />

campaign to deny her tenure, orchestrated by a Barnard alum who lives on an Israeli<br />

settlement. That the crass campaign met with failure is of some comfort amidst the<br />

many-pronged assaults on academic freedom (particularly of scholars on the Middle<br />

East) that has cast a pall on American campus life.<br />

Other forms of silencing in our context are even more direct. On the occasion of<br />

the 40 th anniversary of <strong>Jerusalem</strong>’s occupation (and illegal annexation), the Israeli<br />

Ministry of Interior prevented a conference on the subject, affixing a sign to the<br />

entrance of the hotel where the conference was scheduled that read: “According to the<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 5 ]

law applied in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip of 1995, which organizes activities,<br />

we order not to hold this conference in this hotel or anywhere else in the borders of<br />

the state of Israel.” Once again, a version of the law (this time the interim accords of<br />

1995!) is cited in the banning of expression or, in the idiom of this issue, the looting<br />

of cultural expression and historical truth. In addition to their specific interventions,<br />

we hope this issue makes a modest contribution to opening subjects that have been<br />

forcibly closed.<br />

Penny Johnson, Special Editor for this issue<br />

Endnotes<br />

1<br />

Thanks to Jamil Hilal and Rema Hammami for<br />

sharing this story.<br />

2<br />

Weizman, Eyal 2007. Hollow Land: Israel’s<br />

Architecture of Occupation, London: Verso, p. 40.<br />

3<br />

Slyomovics, Susan 2007. “The Rape of Qula, a<br />

Destroyed Palestinian Village,” in Nakba: Palestine,<br />

1948 and the Claims of Memory (eds. Ahmed<br />

Sa’di and Lila Abu Lughod), New York: Columbia<br />

University Press, 44-45.<br />

4<br />

Abu El-Haj, Nadia 2001. Facts on the Ground:<br />

Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-<br />

Fashioning in Israeli Society. Chicago: University<br />

of Chicago.<br />

[ 6 ] EDITORIAL Why are Those Men in Black Camping Near the Wall?

Ownerless<br />

Objects?<br />

The story of the books<br />

Palestinians left behind<br />

in 1948<br />

Gish Amit<br />

Palestinians fleeing their homes in 1948<br />

with all the belongings they can carry in<br />

their hands. Photo courtesy of UNRWA/<br />

Badil collection<br />

“The Jewish National and<br />

University Library has gathered<br />

tens of thousands of abandoned<br />

books during the war. We thank the<br />

people of the army for the love and<br />

understanding they have shown<br />

towards this undertaking.”<br />

–National Library News, June 1949<br />

Between May 1948 and the end of February<br />

1949, in the course of the 1948 war, 1 the<br />

staff of the Jewish National and University<br />

Library at Hebrew University collected<br />

some 30,000 books, manuscripts and<br />

newspapers that were left behind by the<br />

Palestinian residents of western <strong>Jerusalem</strong>. 1<br />

About 6,000 of those books were then<br />

‘loaned’ to the National Library’s Eastern<br />

Studies department. 2 Furthermore, in 1948<br />

and the following years, the employees<br />

of the Custodian of Absentee Property<br />

gathered some 40,000-50,000 books from<br />

the cities of Jaffa, Haifa, Tiberias, Nazareth<br />

and other places. Most of these books –<br />

largely textbooks found in the schools and<br />

warehouses of the British mandate – were<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 7 ]

later resold to Arab schools. Some 450 were handed over in 1954 to the National<br />

Library’s Eastern Studies Department. Around 26,000 books suffered a worse fate:<br />

in 1957, it was decided that they were “unsuitable for use in Arab schools in Israel,<br />

[because] some of them contained inciting materials against the State, and therefore<br />

their distribution or selling might cause damage to the State” 3 . These texts were sold as<br />

paper waste.<br />

This untold story of the fate of Palestinian ‘abandoned’ books clearly demonstrates<br />

how occupation and colonization is not limited to the taking over of physical space.<br />

Rather, it achieves its fulfilment by occupying cultural space as well, and by turning<br />

the cultural artefacts of the victims into ownerless objects with no past. Israel’s<br />

collection of Palestinians’ books marks the transformation of a lively and dynamic<br />

Palestinian culture into museum artefacts. Thus, Palestinian’ books were placed within<br />

the shrine of Israeli libraries, fossilized on the shelves – accessible and at the same<br />

time completely lifeless. 2<br />

Two central issues will be discussed in this essay. First, it will retrace the months<br />

during which the staff of the National Library followed in the wake of the soldiers,<br />

moving from house to house in search of books and intellectual assets that had been<br />

left behind when thousands of Palestinians fled their homes. The second issue to be<br />

discussed is the conflicted handling of these books – their sorting and classification –<br />

in the years to come.<br />

An image guides my investigation, an image that is by no means fictional. Zionist<br />

fighters march along, followed closely by the librarians of the National Library who<br />

are gathering up the books from all the houses of the neighbourhoods of western<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> – Katamon, Musrara, Talbiya, Bakaa, the German Colony. The soldiers take<br />

over the houses, ‘mop up’ the area, eradicate resistance and secure the roads, while<br />

the librarians, some of whom are serving in the standing army and others who are<br />

‘civilians’ (exempt due to their age or because their work was considered essential),<br />

assemble the cultural and intellectual assets. The librarians emerge from a seemingly<br />

marginal role allotted to them by history, to become part of creating the state’s story.<br />

The work of librarians is facilitated by military action – thus, we have the above-cited<br />

letters of gratitude from library officials to the army and the Custodian of Absentee<br />

Property, whose cooperation was crucial.<br />

Simultaneously, and even as the project was underway, I imagine the first seeds of<br />

hesitation, pangs of conscience and misgivings begin to sprout: are the books ours?<br />

What should we do with them?Are we, the employees of the National Library, looting<br />

the books or only keeping them safe temporarily? If we were to return the books to<br />

their rightful owners, how much should we charge for our efforts?<br />

[ 8 ] FEATURES Ownerless Objects?

But in the midst of war, these hesitations do not affect the enthusiasm and efficiency<br />

of the library staff in carrying out their mission, or their belief that they are engaged<br />

in acts of salvation. And indeed, we must ask: would these books have been preserved<br />

had it not been for the vigorous efforts of these clerks, most of whom were only new<br />

immigrants from central Europe?<br />

The second issue I wish to explore is the library’s conflicted handling of these books:<br />

on the one hand, facilitating a systematic and ongoing separation between the books<br />

and their owners by sorting and cataloguing them into the ‘property’ of the library<br />

and, on the other hand (in a seemingly opposing mindset) keeping the books together<br />

in the National Library’s storerooms marked by a special signature. In the 1950s, the<br />

collected books were marked by the names of their owners whenever possible. In the<br />

1960s, however, the cataloguing system was dramatically altered, erasing the names of<br />

the owners and replacing them with a new signature, “AP” (“Abandoned Property”).<br />

This was a significant change: the books’ connection to their owners was severed, but<br />

the new signature prevented the books from becoming an integral part of the library’s<br />

collections – defacto preserving the Palestinian memory.<br />

Confronting the Past, Silencing Culture<br />

Between December 1947 and September 1949, some 670,000 to 760,000 Palestinians<br />

fled or were expelled from the towns and over 500 villages occupied by the Jews<br />

during the 1948 war. In recent years, following the declassification of most official<br />

political documents of the State of Israel, disclosure of private documents, and<br />

the consolidation of a new critical consciousness, much has been written in Israel<br />

about the war’s catastrophic outcome for the defeated. The works of historians<br />

and sociologists, including Avi Shlaim, Ilan Pappe, Benny Morris, Idit Zartal, and<br />

Baruch Kimmerling, have contributed significantly to this subject by confronting<br />

and exploring the past. We know much more today about the refugees and the way in<br />

which the State of Israel prevented them from returning to their homes. We even know<br />

much about the scope of the refugees’ assets, property, land and factories that were<br />

looted, expropriated and sold, initially to the army and later to the highest bidder. 4<br />

However, little research has been done on the tragic implications of the war for<br />

Palestinian culture. This limited attention to the destruction of Palestinian culture is,<br />

interestingly enough, common to both Israeli and Palestinian discourse.<br />

On 30 April, 1948, renowned educator and Christian Arab writer Khalil Sakakini<br />

fled his home in the Katamon neighbourhood in <strong>Jerusalem</strong> one day after the<br />

neighbourhood was taken over by Haganah forces. His diaries, which have been<br />

partly translated into Hebrew, reveal to Israeli readers a fairly broad picture of life in<br />

Palestine, beginning with the optimism of the 1920s and ending with the miseries of<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 9 ]

war and exile in Egypt, where Sakakini died in 1961. In his escape from <strong>Jerusalem</strong>,<br />

Sakakini left behind not only his house and furniture (the grand piano, electric<br />

refrigerator, liquor cabinet and narghilah), but also his books, to which, two months<br />

after he had settled in Cairo, Sakakini bade farewell with emotion and pathos:<br />

Farewell, my library! Farewell, the house of wisdom, the abode of philosophers,<br />

a house and witness for literature! How many sleepless nights I<br />

spent there, reading and writing, the night is silent and the people asleep…<br />

goodbye, my books!... I know not what has become of you after we left: Were<br />

you looted? Burnt? Have you been ceremonially transferred to a private or<br />

public library? Did you end up on the shelves of grocery stores with your<br />

pages used to wrap onions? 5<br />

We now know what became of that library: Tom Segev, who made Sakakini one of the<br />

protagonists of his book on Palestine during the British Mandate, notes in a footnote<br />

what he learned from Sakakini’s daughter, Hala, who in the summer of 1967 visited<br />

the Jewish National and University Library with her sister and discovered there her<br />

father’s books scrawled with his handwritten notes. 6<br />

Palestinian Books: Collection and ‘Guardianship’<br />

On 10 and 16 June, 1948, the first two letters were written that specifically referred<br />

to the gathering of Arab books. The first is a letter sent by Hebrew University<br />

administrator David Senator to the Jewish Agency’s directorate for “urgent discussion”<br />

at the “appropriate Israeli government ministry”. A memo written by Kurt Warman,<br />

director of the National Library, and entitled “on the urgent need for a central<br />

custodian authority for handling the matter of public and private abandoned books and<br />

libraries” was attached to Senator’s letter. In the memo, Warman implores the Israeli<br />

government to grant the National Library the status of:<br />

a central certified authority, whose task would be to handle the issue of<br />

abandoned libraries, whether private or public… [Because] in our opinion,<br />

the National Library is the most suitable institution for reception and<br />

guardianship of the aforementioned books. The National Library has the<br />

means to see that the books are properly preserved, and to return them to<br />

their rightful owners, should such come forward. 7<br />

The second document, dated 16 June, is a short eight-line letter written by Yisaschar<br />

Yoel, Warman’s deputy. The letter, which is a report on the National Library’s<br />

condition, concludes with the following words: “Our book collecting project reached<br />

the Musrara neighbourhood yesterday.” 8 How can we interpret these two documents,<br />

the first a measured administrative argument for authority and guardianship to<br />

[ 10 ] FEATURES Ownerless Objects?

preserve Palestinian books, the second a brief sentence from the ‘field’ where the<br />

books are being acquired, the formerly Palestinian neighbourhood of Musrara, near the<br />

walls of <strong>Jerusalem</strong>’s Old City.<br />

I find these documents odd and unexpected. 9 What is meant by Warman’s memo,<br />

which throws us immediately into the deep water of the issue of ownership? And<br />

what lies behind Yoel’s ten words mentioning the collection of books so incidentally,<br />

apropos other things? At this moment I think of the limitations of this research,<br />

and perhaps – if I am not overreaching – of the boundaries limiting the work of<br />

the historian: her dependency on documents, and all the documents that she does<br />

not succeed in finding (due to inability or overflowing archives or simply missing<br />

what one is seeking). I once again ponder Yoel’s ten words: I am entranced by their<br />

simplicity and openness, by the straightforward manner in which they lay before us<br />

this historical event, in an almost naïve gesture. At the same time, I cannot but feel<br />

troubled by the events, words and actions that lay behind them. 10 What are the books<br />

in question? Who does the word “our” refer to? Who are the collectors? And where<br />

did they collect books on the previous day?<br />

It is necessary to read many more documents before we can answer these questions,<br />

decipher them, and realize that these words characterize the entire affair of the<br />

‘collection’ of Palestinians’ books: a constant and ongoing movement between<br />

exposure and concealment, between explicit statements and vague, almost alienated<br />

general rhetoric, which naturally plays a political role.<br />

Owners on the Margins: The Question of Return<br />

Warman’s memo explicitly mentions custodianship, not ownership. Between May and<br />

the beginning of August 1948, the official treatment of the books was one of restraint.<br />

In all the letters, reports and memos from this period, the staff of the National Library<br />

reiterates the stance that the Palestinians’ books have been entrusted to the Library for<br />

indefinite guardianship. In all of these documents there appear, if only in the margins,<br />

legal owners who may one day return. I believe it would be wrong to claim that the<br />

books’ owners were the primary concern of the National Library’s employees although<br />

they may have believed that the books would one day be returned. This may explain<br />

why the Library’s eagerness to receive the books has not yet taken on an overtly<br />

possessive shape.<br />

Here is where the work of interpretation is essential, but also where the act of<br />

interpretation becomes so charged. Some would consider Dr. Warman’s appeal to the<br />

Custodian a testimony of his careful treatment of the books and his sincere efforts<br />

to ensure the property’s safety and preservation. I, on the other hand, am inclined<br />

to read these words – with their urgent claim for ownership only two weeks after<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 11 ]

the collection project had begun – as revealing a man indifferent to the implications<br />

and context of his actions. Where others may see restraint, I mostly find an efficient,<br />

disturbingly cold professionalism. And even if we assume for a moment that Warman,<br />

a product of German education and 19 th -century positivism, yearned for the “good<br />

order of things”, doesn’t this desire itself prompt an uneasy feeling? Furthermore,<br />

Warman’s stated objective was to prevent chaos in the collection of books. There is,<br />

of course, much logic to Warman’s demand that one authority should be appointed to<br />

handle, sort and distribute the books, and it was not unlikely that this authority should<br />

be his own. He himself notes:<br />

The National Library possesses the mechanism most capable of handling<br />

all the problems, which are many and very often complicated, having to<br />

do with these books… [and it also possesses] the biggest catalogue in the<br />

country which makes the bibliographical identification and processing of<br />

the books easier. 11<br />

He adds that, as the books are in Arabic, “the National Library employs the most<br />

experienced expert librarians for this sort of literature, as well. In passing, Warman<br />

also mentions:<br />

The absence of an official authority recognized by the civilian and military<br />

leadership has significantly obstructed and is still obstructing the rescuing<br />

of the books. Among the many difficulties that stand in our way, there<br />

should be mentioned the inappropriate phenomenon of competition between<br />

different public institutions over the find.<br />

Remarkable in this last sentence is not only its rhetoric, which turns the act of<br />

confiscation into an act of ‘rescuing’ and the books themselves into a ‘find’, but<br />

also the matter at hand. It is clear there was a struggle between various institutions<br />

seeking to obtain the books, as well as greed among these institutions (some only<br />

recently founded) and impatience with the appropriation and distribution of the books.<br />

Warman’s appeal “of the most pressing urgency” may have been born, in fact, from his<br />

interest in the prestige of the National Library in a competition with other libraries and<br />

government offices, as well as his own ambitions and professional career.<br />

This document seems to point to some of the book affair’s most obvious<br />

characteristics: a mixture of arrogance, greed and indifference hidden under the<br />

guise of professionalism; the inseparable combination of occupation and passion for<br />

acquiring possessions; a fear of losing books; but also a banality of action, where the<br />

extraordinary becomes an ordinary matter of administration.<br />

[ 12 ] FEATURE Ownerless Objects?

A Safe Place for ‘Magnificent Arab Libraries’<br />

In July 1948, western <strong>Jerusalem</strong> was under Jewish control and of the thousands of<br />

Palestinian residents of the western city, only about 750 non-Jews remained in the<br />

area, mostly non-Arabs. 12 The issue of looting and robbery by the conquering army<br />

was discussed by the Jewish public. Al-Hamishmar newspaper reported the conquest<br />

of the village of Malha, its reporters denouncing increasing looting and robberies. At<br />

the beginning of the month, the paper reported a new law, the “Emergency Regulations<br />

(Absentees’ Property)”, which obligated registration of absentees’ assets, noting<br />

that “finally, the police chiefs and city leaders have waged a war on the looting and<br />

robbery… Katzin Sofer, the head of the <strong>Jerusalem</strong> Police, has announced that great<br />

efforts are being carried out to find those responsible for the pillaging in the occupied<br />

territories in <strong>Jerusalem</strong>; those efforts have already yielded some initial results.” 13<br />

On 26 July, we find a letter to Dr. Warman, the head of the National Library, by an<br />

unknown writer:<br />

According to my estimates, 12,000 books or more have been collected so far.<br />

A large portion of the libraries of Arab writers and scholars is now in a safe<br />

place. Several bags of manuscripts, whose value has not been evaluated yet,<br />

are also in our hands. Most of the books come from Katamon, but we have<br />

also reached the German Colony and Musrara. We found some magnificent<br />

Arab libraries in Musrara. We also removed from Musrara part of the<br />

Swedish School’s library. The winds have not yet quieted in this area, but I<br />

hope we can continue there in the coming days. After Dr. Unger complained<br />

to me that we have not tried hard enough to save medical libraries, I took<br />

out in the recent days the library of the health department in the German<br />

Colony. The Israeli Government’s <strong>Jerusalem</strong> Health Department was quick to<br />

claim it, but we are in negotiations and I hope we can reach an agreement…<br />

several days ago, the university allotted for this action 2-3 of its workers.<br />

This has improved the productivity of the project which until now has been<br />

in the hands of only three people: Goldman, Eliyahu and myself. And even<br />

those did not do it daily, but in intervals. We received a room at Bergman’s<br />

house, and also discovered a small storeroom in Itingon’s house. These two<br />

rooms have solved the problem of space for now. 14<br />

This letter provides us with some important details: it notes the number of books that<br />

have been collected in the first three months of the city’s western occupation; it specifies<br />

the neighbourhoods from which the books have been taken; and it discloses that books<br />

were not only taken from private houses, but also from public institutions, in this case<br />

the Christian Arab School in the Katamon neighbourhood. In addition, the letter implies<br />

disagreements between the librarians as to which books should be collected, and also<br />

indicates the government’s eagerness to grab the plunder despite issues of ownership.<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 13 ]

Two other things seem worthy of mention. First, here we are witnessing a moment that<br />

strikingly illustrates the way in which one culture emerges from the ashes of another;<br />

the ruin of Palestinian culture is the birth moment of a new Israeli consciousness based<br />

not only on erasing the Palestinians’ presence, but also on erasing their culture. Once<br />

the culture is erased, one can claim that it never existed – there is nothing to contradict<br />

or refute this conception. 15 Second, this letter not only underscores the act of takeover,<br />

but also its rhetoric: the books, which have been scattered everywhere, have finally<br />

come to rest in a safe place.<br />

Processing Arab Books: A Right and a Service Rendered<br />

At about the same time that this letter was sent to Dr. Warman (perhaps a bit earlier)<br />

the head of the Eastern Sciences Department at the National Library, Dr. Strauss,<br />

published a memo entitled, “Processing the Arab books from the occupied territories”.<br />

It was Strauss’ responsibility to receive the books, catalogue them and store them. His<br />

words attest both to his excitement at the growing influx of books, as well as to his<br />

resulting confusion and distress. It was a time of complete and total chaos; he found it<br />

difficult to handle the thousands of books and sort them properly, and his requests for<br />

help and more assistants have thus far been denied. In addition, the National Library<br />

had been forced to relocate from the Wolfson Building on the Mount Scopus campus<br />

to the Terra Sancta Building in western <strong>Jerusalem</strong>. The first part of the document<br />

reads:<br />

Since the National Library was granted the right to collect abandoned libraries<br />

in the occupied territories and began a comprehensive operation in<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong>’s Arab neighbourhood, nearly 9,000 books have been assembled.<br />

The number of books that were brought to the library in this way is greater<br />

than the number of Arabic books that have been collected by us throughout<br />

the years of this institution’s existence. And not only this, but also among the<br />

books that have been found in the occupied territories there is a substantial<br />

number of books that have not been in our possession before, and many<br />

newspapers (nicely bound) that are not in the National Library’s archive.<br />

Seeing that when approaching this task we have before our eyes the possibility<br />

of receiving some of the books as a fee for our services, indeed we<br />

have been given the opportunity to expand our collections considerably.<br />

However, in order to take advantage of this opportunity, we must invest<br />

much work in arranging and processing the books, which are in the meantime<br />

packed in sacks. Since the rules that would apply to these books have<br />

not been set yet, it is fitting that lists are compiled in a manner that would<br />

make it easier to reach an agreement in case the books are returned to their<br />

previous owners. For the authorities (the Israeli government and military<br />

governors) we shall provide lists that include the name of the author and<br />

[ 14 ] FEATURES Ownerless Objects?

of the book alone, and for the libraries’ owners also there is no need to go<br />

into more detail. Taking into account that our work is currently not being<br />

carried out in the National Library itself, and since it is possible that the<br />

books will once again be placed in crates and carried to Mount Scopus, it<br />

would be advisable to mark each book with the same number that would<br />

appear on the lists… in order to make it easier to select the books we are<br />

to receive as a fee for our services – if such an arrangement is agreed upon<br />

– the list should be divided according to the subjects the books belong to,<br />

such as old and modern literature, humanities, sciences, etc. 16<br />

The expression “The National Library has been granted the right” is very important,<br />

because it indicates that the collection of books has been carried out with official<br />

and military permission. It is also important because of its sanctimonious tone,<br />

which bleaches the sin by turning the library into a passive body. However, I want to<br />

concentrate on what I feel is the most important concept in this letter, the term “fee<br />

for services rendered”. How are we to understand it? Is this a spectacular display of<br />

sophisticated apologetics, the rhetorical trick of an administrator conscious of the fact<br />

he is writing an official, perhaps even public, document and who is therefore trying<br />

to conceal his eagerness to adopt the books under the cloak of future distribution<br />

arrangements? Alternately, is it possible that Strauss honestly believed that the<br />

National Library had performed an act of grace and salvation, and therefore deserved<br />

a reward for its efforts? Either way, it is clear that Strauss, like his colleagues,<br />

recognized the value of the books, coveted them, and had no intention of giving them<br />

up easily. If we have any doubts, the following sentences in the memo make this clear:<br />

If a substantial number of these books is given to the National Library, we<br />

would be able to dramatically expand our research opportunities. Doubtless,<br />

we have first to bring into the National Library those books that are not<br />

currently in our possession. As for the other books, we are mainly interested<br />

in classical literature publications… examining the books that have come<br />

into our hands therefore requires library processing with exact awareness<br />

of our needs, and it should be noted that in this aspect, the Eastern Department<br />

at the National Library far surpasses similar institutions in the rest of<br />

the Near East countries that, although they are wealthy in books, are not<br />

adequately organized and do not allow the reader and the researcher the<br />

kind of work that can be done here. 17<br />

The conditional that appears at the beginning of the quote should not distract us from<br />

the fact that Strauss had a solid answer to the question of what should be done with the<br />

books; in fact, it underscores it.<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 15 ]

The National Library and Orientalisation<br />

The book looting cannot be understood without first tracking the history of the<br />

National Library. Since the establishment of the Hebrew University in 1925, the<br />

National Library had been intended to serve both as an archive for Israeli and Jewish<br />

culture over the years, and – in the words of Chaim Nahman Bialik who spoke at the<br />

university’s groundbreaking ceremony – to serve as a place whose windows are “open<br />

to the four winds… to bring to it all that is good and sublime from the fruits of man’s<br />

creative mind in all times and in all countries.” 18 This attitude is what allowed Arab<br />

texts, including scripture, literature, science, and foreign language books, to become<br />

integrated in the National Library, namely to become part of ‘our’ knowledge of the<br />

East. In short, discussion of this book affair cannot be complete without returning to<br />

Edward Said, who taught us that the Orient (like the Occident) is not a fixed fact of<br />

nature – they are both the creation of man. Said would probably have claimed that<br />

the books were orientalised not only because they were discovered as ‘oriental’, but<br />

also and mainly because it was possible to force them into becoming ‘oriental’. He<br />

also would have reminded us that this book affair is related to that enormous chain<br />

of power relations and interests, supervision and control, that decides who should be<br />

allowed to talk (represent the Orient), and who will remain silent, voiceless, devoid of<br />

the opportunity to represent himself.<br />

The role played by the Eastern Department of the National Library in the looting of<br />

Palestinian books expressed two of its functions. On the one hand, it was home to<br />

celebrated Orientalists, Zionist intellectuals who were educated at Middle Eastern<br />

studies departments in Britain and Germany (Dr. David Bennett, Prof. Guthold Weill,<br />

etc.), scholars who were not only librarians, but also central figures at the Oriental<br />

Studies Institute in Hebrew University and for whom the collection of these books<br />

was part of a wider task of mapping and understanding the East. On the other hand,<br />

the department accommodated Arab librarians 19 as well as librarians from eastern<br />

countries (mainly from Iraq) in the daily work of collecting and cataloguing the books.<br />

Their work once more reveals to us how the eastern Jews, themselves the object of the<br />

Israeli and Ashkenazi establishment’s orientalism, have become major players in the<br />

oppression of the Arabs. 20<br />

In Love with Plunder<br />

Strauss’ memo is also notable for its quick adjustment to the new situation, including<br />

a daring leap towards the creation of the ‘obvious’, where the books are not ours,<br />

but yet are already entirely ours, only months after the process of their collection<br />

began. A similar process was occurring not far from the National Library in the new<br />

government offices, as Benny Morris delineates in his book about the creation of<br />

[ 16 ] FEATURES Ownerless Objects?

the refugee problem and the dispossession of refugee property. The workers of the<br />

National Library did not know what to do with the books initially, and therefore<br />

made various statements about their possible future return to their owners, subject to<br />

hard-to-meet conditions and restrictions. After a while, no one was willing to discuss<br />

seriously returning the books to their owners, who were already far from <strong>Jerusalem</strong> at<br />

that point.<br />

I wish to complete this short chronicle of the pillaging of the books with one last<br />

document. 21 Its importance lies in the manner that it bleaches and purifies this sin,<br />

until no sign of violence and wrongdoing remains. It is not only the occupation, the<br />

expulsion of the Arabs and the taking of their libraries that evaporate, but also the<br />

pangs of conscience, if such ever existed (and I believe that they did), that disappear.<br />

Those who read this document without knowing the history of the war might easily<br />

come to think that the Palestinians left their houses willingly, for some reason leaving<br />

behind tens of thousands of abandoned books for the staff of the National Library to<br />

rescue fearlessly.<br />

The National Library publishes an annual booklet entitled, The National Library’s<br />

News, detailing the institute’s major recent acquisitions, relevant academic<br />

publications, and information about other events of importance. In the report for the<br />

period between January 1948 and June 1949, it says:<br />

Throughout the years of fighting, the National Library has collected tens of<br />

thousands of abandoned books, thus saving them from ruin. This operation<br />

has been carried out with dedication and sacrifice on the employees’ part.<br />

We wish to take this opportunity to thank the people of the army and the<br />

custodians of the relevant government ministries, for their great help and<br />

the understanding and love they have shown, and are still showing, to this<br />

important work. 22<br />

According to this description, Palestinians should be grateful and cherish the Zionist<br />

librarians’ momentous efforts: if it hadn’t been for them, who knows what would have<br />

become of their libraries? The document goes even further, however, implying that the<br />

Palestinians’ books never had any owners in the first place. The books were simply<br />

‘found’, scattered at the mercy of passersby, an anonymous pile of books one might<br />

stumble upon in the street.<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 17 ]

The Owners of the Objects<br />

Following is a partial list of the dozens of book-owners whose names appeared on the<br />

report submitted to the National Library’s directorate in March 1949: 23<br />

Ajaj Nuwaihid – Bakaa<br />

Hanna Sawida – Katamon<br />

Khalil Baydas – Bakaa<br />

George Sai’d – Bakaa<br />

Michael Kattan – Bakaa<br />

Saliman Sa’ed – Bakaa<br />

Aref Hikmet Nashashibi – St. Paul St.<br />

George Khamas – Katamon<br />

Khalil Sakakini – Katamon<br />

Henry Kattan – Bakaa<br />

Attorney Saa – Musrara<br />

Yousef Heikal – Katamon<br />

Tawfik al-Tibi – Katamon<br />

Francis Khayyat – Musrara<br />

Hagob Malikian – Talbiya<br />

Emil Salah – German Colony<br />

Z. T. Dajani – Railroad station neighbourhood<br />

S. A. Awad – Katamon<br />

Fuad Abu Rahma – Katamon<br />

Adel Hasan al-Turjeman – St. Paul St.<br />

Niqola Faraj – Musrara<br />

M. Hanoush – Talbiya<br />

And the list goes on and on, a fading remembrance booklet of the lost and looted<br />

books of Palestinians and Palestinian culture. Can they be saved from oblivion?<br />

Gish Amit is a PhD student and a lecturer in the Hebrew Literature Department at Ben Gurion<br />

University.<br />

[ 18 ] FEATURES Ownerless Objects?

Bibliography<br />

Ginzburg, Carlo, “Checking the Evidence: The<br />

Judge and the Historian”, Critical Inquiry, vol.<br />

18, no. 1, 79-92.<br />

Kimmerling, Baruch, Immigrants, Settlers,<br />

Natives: State and Society in Israel – Between<br />

Multiculturalism and Culture War, Tel Aviv, Am<br />

Oved Publishing House, 2004. [Hebrew]<br />

Morris, Benny, The Birth of the Palestinian<br />

Refugee Problem, 1947-1949, Tel Aviv, Am<br />

Oved Publishing House, 1991. [Hebrew]<br />

Pappe, Ilan, “The New History of the 1948 War.”<br />

Theory and Criticism 3, Winter 1993, 99-114.<br />

[Hebrew]<br />

Said, Edward, Orientalism, Tel Aviv, Am Oved<br />

Publishing House, 2004. [Hebrew]<br />

Shafrir, Dov, A Flowerbed of Life, Tel Aviv,<br />

Agricultural Center Publishing, 1975. [Hebrew]<br />

Shlaim, Aviv, The Iron Wall – Israel and the Arab<br />

World, Tel Aviv, Yedioth Ahronoth Publishing<br />

House, 2005. [Hebrew]<br />

Shunami, Shlomo, On Libraries and<br />

Librarianship, <strong>Jerusalem</strong>, Reuven Mass<br />

Publishing House, 1969. [Hebrew]<br />

Zartal, Idit, Death and the Nation – History,<br />

Memory, Politics, Israel, Dvir Publishing House,<br />

2002. [Hebrew]<br />

Endnotes<br />

1<br />

State Archives, <strong>Jerusalem</strong>, (hereafter SA) GL-<br />

429/3.<br />

2<br />

Most of the books are still kept in the storerooms<br />

of the Jewish National and University Library in<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong>.<br />

3<br />

SA GL-1429/5.<br />

4<br />

Tamar Berger, Dionysus at the Mall (Israel:<br />

Hakibbutz Hame’uhad Publishing House, 1998)<br />

[Hebrew]; Tom Segev, 1949 – The First Israelis<br />

(<strong>Jerusalem</strong>: Domino Publishing House, 1984)<br />

[Hebrew]; and Dalia Habash and Terry Rempel,<br />

“Assessing Palestinian Property in West <strong>Jerusalem</strong>”’<br />

in <strong>Jerusalem</strong> 1948: The Arab Neighbourhoods and<br />

Their Fate in the War, ed. Salim Tamari (<strong>Jerusalem</strong>:<br />

The Institute of <strong>Jerusalem</strong> Studies & Badil Resource<br />

Centre, 1999) 154-183.<br />

5<br />

Khalil Al-Sakakini, This is the Way I Am,<br />

Gentlemen!, Translated by Gideon Shilo (<strong>Jerusalem</strong>:<br />

Keter Publishing House, 1990) [Hebrew] 239-240.<br />

6<br />

See Tom Segev, Days of the Anemones, the Land<br />

of Israel During the British Mandate (<strong>Jerusalem</strong>:<br />

Keter Publishing House, 1990) [Hebrew].<br />

7<br />

Hebrew University Archives, <strong>Jerusalem</strong> (hereafter<br />

HUA), 042/1948.<br />

8<br />

National Library Archives, <strong>Jerusalem</strong> (hereafter<br />

NLA), 793/200.<br />

9<br />

As a researcher I feel that I should defend myself<br />

from them, in light of what appears to me to be open<br />

and unrestrained aggression, which instantly throws<br />

me into the heart of this affair. Had I been given<br />

the privilege, I would have preferred to become<br />

acquainted with the events of those days more slowly.<br />

I would ask the documents to show patience, I would<br />

urge them to reveal themselves in a more measured<br />

way. However, they are manifestly raring to go, and<br />

they demand from me – almost force me – to move<br />

faster.<br />

10<br />

To put things differently, I believe that the magic<br />

in these words is somehow connected to a certain<br />

kind of inner contradiction. They tell us, without<br />

embellishment, everything we wish to know, and at<br />

the same time they make us feel as if so much has<br />

been left beyond our reach. They tell us so much, and<br />

at the same time so little.<br />

11<br />

NLA 793/200.<br />

12<br />

See Nathan Krystall, “The Fall of the New<br />

City 1947-1950”, in <strong>Jerusalem</strong> 1948: The Arab<br />

Neighbourhoods and Their Fate in the War, ed. Salim<br />

Tamari (<strong>Jerusalem</strong>: The Institute of <strong>Jerusalem</strong> Studies<br />

& Badil Resource Centre, 1999) 92-146.<br />

13<br />

Al-Hamishmar, 1 July, 1948.<br />

14<br />

NLA, 793/200.<br />

15<br />

I think, for instance, of Hirbet Hiz’a by the Israeli<br />

novelist S. Yizhar. Even there, in the heart of this<br />

brave attempt to reveal things that have been buried<br />

and repressed, the Arabs remain farmers. And I also<br />

think of myself, the son of a bourgeois, middle-class<br />

family, with parents who voted for Meretz their entire<br />

lives. Did I ever encounter in my childhood the names<br />

of Arab novelists? As far as I can remember, I did not<br />

even imagine it.<br />

16<br />

NLA 793/200.<br />

17<br />

Ibid.<br />

18<br />

Menachem Megidor, “Preface” in Hidden<br />

Treasures – From the Collections of the Jewish<br />

National and University Library, eds. Rafael Wizser<br />

and Rebecca Palsar (<strong>Jerusalem</strong>: Hebrew University,<br />

2000) 7 [Hebrew].<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 19 ]

19<br />

I recently had the opportunity to speak with two<br />

of them, Aziz Shihadeh, an attorney from Nazareth<br />

who worked at the library from 1963 to 1966, and<br />

Butrous Abu Manneh, a professor of Middle Eastern<br />

history at the University of Haifa, who worked at the<br />

library from 1956 to 1958. Shihadeh told me of:<br />

big sacks of flour containing books. We knew<br />

that these were books of Arabs from 1948. The<br />

sacks were put behind the department’s reading<br />

hall. We would get dozens of sacks, sometimes<br />

even a hundred, and catalog them.<br />

GA: Did this bother you?<br />

AS: No, at that time it did not bother me. The<br />

person is more important than the book. If the<br />

people have been exiled and dispersed across<br />

the world, what good does the book do? It’s good<br />

the books were not burned. There are people who<br />

would have burned them.<br />

GA: Why do you think the books were not<br />

burned?<br />

AS: The Jews appreciate the book. They are a<br />

civilized people. They are not barbarians. And<br />

besides, had the books been left to the street<br />

children, they would have ransacked or destroyed<br />

them. People in the street would not have<br />

valued these books. (Aziz Shihadeh, meeting in<br />

Nazareth, 28 Feb., 2007)<br />

Abu Manneh told me similar things: “I appreciate the<br />

initiative to bring together and preserve these books.<br />

This really is a civilized act – or else the books would<br />

have been lost. I’m sure that the act was sincere and<br />

based on the notion that at stake were cultural assets<br />

that should be preserved. The people of the library<br />

were decent.” (Butrous Abu Manneh, meeting in<br />

Haifa, 14 March, 2007)<br />

20<br />

In this context, and in the current stage of my<br />

work, I cannot help but think about the fact of my<br />

being an Israeli. I thought about it when I met with<br />

Knesset Member Jamal Zahalka, who approached the<br />

National Library several years ago with a request to<br />

return Khalil al-Sakakini’s books, a request which<br />

was answered with the following reply: “We are<br />

unable to discuss your request until the list of books<br />

is handed to us.” (Needless to say that such a list<br />

could have only existed in the hands of the National<br />

Library.) Zahalka was courteous and tried his best<br />

to assist me. However, and for no apparent reason, I<br />

could not help but feel that he was looking me over<br />

with suspicion and that his tone was tinged with irony<br />

towards me, a somewhat questionable interviewer,<br />

seeking to speak on behalf of those whose voice<br />

had been taken from them, and at the same time a<br />

descendent of the disinheritors.<br />

21<br />

NLA, 793/200. A last note: this study owes its<br />

existence to archives. Two things occur to me in this<br />

context. First, the gap between the chaos of war, at<br />

least as it is usually conceived, and the methodical<br />

nature of documentation. I am convinced that there<br />

are many things of which nothing has been said,<br />

and of which nothing remains: undocumented<br />

conversations, letters that were lost forever, oral<br />

agreements and operations that went unmentioned.<br />

However, I cannot but be impressed by the plentiful<br />

documents kept in the archives, which I believe reveal<br />

more than just the mechanism of administration.<br />

Secondly, much has been said about the power of<br />

the archive, its incessant aggression and the varied<br />

ways in which it serves the regime. All this is true,<br />

but still, archives may also undermine the same order<br />

on whose behalf they are supposed to function. These<br />

spaces, which zealously preserve the incriminating<br />

testimonies and the evidence that might, some day,<br />

indict their owners, could undermine teleological<br />

narratives which unravel in a seemingly undisturbed<br />

manner. Because it is the documents, so zealously<br />

kept, which expose the breaks, the rifts, the cuts and<br />

the transformations that imperial history seeks to<br />

hide. By preserving remnants and partial, incomplete<br />

objects, archives have the power to act against<br />

imperial history and at the same time lead us towards<br />

more fragile, uncertain dimensions.<br />

22<br />

It seems that since then, this version of events has<br />

become fixed in the National Library’s consciousness.<br />

In an exhibition that was held in 1965 marking 40<br />

years since the Hebrew University’s inception, the<br />

1948 war was given a place of honor. However,<br />

the book affair was summed up very simply in<br />

the catalog: “During the Liberation War, many<br />

abandoned Arab books were found.” (The National<br />

Library, An Exhibition Marking 40 Years Since the<br />

Hebrew University’s Foundation (<strong>Jerusalem</strong>: The<br />

National Library and the Hebrew University, 1965)<br />

36).<br />

23<br />

SA, GL-1429/3.<br />

[ 20 ] FEATURES Ownerless Objects?

The Trade in<br />

Palestinian<br />

Antiquities<br />

Morag M. Kersel<br />

The Tomb of the Shepherd of Moses in the<br />

Judean desert was recently excavated by<br />

looters and left as depicted here.<br />

Photo credit: Adel Yahya/PACE<br />

Today, a visitor to <strong>Jerusalem</strong> can visit<br />

a licensed dealer and lawfully purchase a<br />

piece of the past, courtesy of the legallysanctioned<br />

(under prevailing Israeli<br />

legislation) trade in antiquities. This<br />

trade is fuelled by a supply of antiquities<br />

acquired via both licit and illicit channels. 1<br />

Despite numerous studies 2 showing a<br />

direct relationship between the demand for<br />

archaeological material and the looting of<br />

archaeological sites, the current government<br />

of Palestine is also considering a legalized<br />

sale of antiquities. 3 The origins of the legal<br />

sale of antiquities in Israel and Palestine can<br />

be traced back to the Ottoman occupation of<br />

the region, which encouraged the movement<br />

of artefacts from the hinterlands to the<br />

capital. The legal precedents for the trade are<br />

also a legacy of the Mandate period, during<br />

which the British Mandate government<br />

established both the legal and logistical<br />

framework for the current antiquities<br />

scheme in Israel and the proposed law in<br />

Palestine. Although historically entrenched,<br />

is the continued use of these legislative<br />

legacies the best mechanism for protecting<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 21 ]

the cultural heritage of the region? In this paper, I consider the ramifications of<br />

cultural heritage law and practices which authorize a trade in antiquities–the historical<br />

antecedents, the current practice, and the future initiatives–theoretically aimed at<br />

protecting the past for future generations.<br />

The establishment and implementation of laws is not without its tribulations, whether<br />

in the past or present. Archival evidence from the British Mandate period illustrates<br />

many of the problems and pitfalls associated with the execution and oversight of the<br />

managed trade in antiquities in Palestine during the Mandate. Many of the challenging<br />

elements of the trade discussed in the correspondence and records of the Mandate<br />

Department of Antiquities continue to plague the current licensed trade in antiquities<br />

in Israel; they portend similarly vexing issues of an ill-conceived law in Palestine.<br />

Through archival documentation and oral histories with the various participants in<br />

the legal trade in antiquities, this study considers the legal genesis of the existing<br />

and proposed antiquities laws in Israel and Palestine. Integral to an investigation of<br />

these laws is the question of ownership and control of the past, and the future sale of<br />

archaeological artefacts in the region.<br />

Owning the Past?<br />

Christian, Jewish, and Muslim pilgrims have long been enticed to the land of the<br />

Bible. As early as the second century CE, the first Christian pilgrims from various<br />

parts of the Roman Empire began to arrive in Palestine to recreate the lives of Jesus<br />

and the Apostles. The efforts of Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine were<br />

among the first attempts to identify the sites of the Bible. Helena was not content<br />

to merely walk in the footsteps of Jesus, but wished to find the actual locations of<br />

Biblical events and to enshrine them for future pilgrims. 4 With this began the era of<br />

Byzantine pilgrimage. 5 The motivations of these early intrepid travellers extended<br />

beyond visiting sites, but for the first time the associated archaeological artefacts<br />

began to take on significance–they signified a place associated with the Bible and were<br />

to be venerated wherever their final resting place.<br />

Bones of saints, garments and shrouds of New Testament figures and virtually<br />

every sort of relic associated with famous biblical personalities were dug<br />

up, bought, sold, and highly prized for their spiritual and healing power. By<br />

the end of the fourth century CE, the export or ‘translation’ of relics from<br />

the Holy Land had reached enormous proportions. 6<br />

Early pilgrims were encouraged by church officials to acquire relics, establishing the<br />

mechanisms for buying and selling sacred paraphernalia and creating an important<br />

source of revenue for the monastic and religious establishments in the Holy Land.<br />

[ 22 ] FEATURES The Trade in Palestinian Antiquities

Hebron Cottage Industry. Source: M. Kersel<br />

Pieces of the True Cross, Jesus’ burial shroud, vials of Mary’s milk, and body parts of<br />

the various saints were sold at the various religious institutions frequented by pilgrims.<br />

The value of these relics and the myriad conflicting claims to possession of identical<br />

relics led to an even greater emphasis on the objects themselves. A small cottage<br />

industry for the production of relics to meet market demand grew up in the areas<br />

surrounding the religious sites (Bethlehem, Hebron, and <strong>Jerusalem</strong>). 7<br />

The Muslim rulers of the seventh century CE onwards made no real objections to<br />

continued Christian pilgrimage to the area, until the destruction of the Church of<br />

the Holy Sepulchre in 1009 by the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim. The ensuing Crusades<br />

were a battle for the ancient shrines and artefacts of the region; trade in relics and<br />

seasonal religious tours continued and acted as manifestations of economic and<br />

political connections between European cities and the trade networks of the region.<br />

Control over the various very lucrative religious sites became a central issue in many<br />

international struggles throughout the Middle Ages and Ottoman period.<br />

The subsequent growth of antiquarianism in the eighteenth century gave rise to a new<br />

secular interest in the area. The once purely religious interest in the Holy Land began<br />

to give way to a more down-to-earth curiosity about its artefacts, monuments, plants,<br />

people, and ruins. Those on the Grand Tour collected to fill their cabinet of curiosities<br />

rather than expressly for religious reasons. Explorers avidly amassed samples of<br />

classical statuary, coins, and pottery. Academic understanding of the history of the<br />

region was for the first time independently expanded through the study of material<br />

artefacts. The interest in acquiring artefacts for scientific purposes, coupled with<br />

the continued demand for religious relics and icons fuelled the trade in antiquities,<br />

although the trade went unregulated and there were no governmental mechanisms<br />

in place to protect the cultural heritage of the region. Public awareness of artefacts<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 23 ]

as commodities, consumer demand and perceived threats to the material past played<br />

integral roles in the development of the laws governing legal and illegal trade.<br />

Later legislative efforts of the Ottoman Empire and the subsequent British Mandate<br />

government in the area sought to rectify the depletion of relics and the attendant<br />

mining of archaeological sites to supply the ever-increasing demand.<br />

Legal Antecedents<br />

The Ottoman Law of 1884<br />

In response to increasing foreign interest in the area and the looting of archaeological<br />

material from the Empire, 8 an early Ottoman Antiquities Law was passed in 1874 for<br />

the regulation of antiquities trafficking. This first antiquities law was primarily aimed<br />

at foreign nationals and was written as a protection mechanism. A later Ottoman law<br />

enacted in 1884 (1884 Law) established national patrimony (ownership) 9 over all<br />

artefacts in the Ottoman Empire and sought to regulate scientific access to antiquities<br />

and sites (excavation permits were required). Under the law, all artefacts discovered<br />

during excavation were the property of the National Museum in Constantinople and<br />

were to be sent there until those in charge made decisions about the disposition of the<br />

finds. This law could be considered the first instance that archaeological material from<br />

the region was deemed important enough to pass legislation to ensure its safekeeping.<br />

Alternatively the law could be construed as legalized cultural imperialism 10 –motivated<br />

by the Ottoman Empire’s desire to appropriate material from its territories rather<br />

than for the preservation of the archaeological legacy of the region. By controlling<br />

archaeological goods and taxing the antiquities sales in the periphery, the government<br />

effectively regulated European access to heritage, access that had been previously<br />

unfettered.<br />

Most of the provisions articulated in the 1884 Law seemed reasonable, but practical<br />

enforcement of this law was virtually impossible. The expanse of the empire was<br />

so great that the Ottoman government did not have enough officials to oversee and<br />

implement the various regulations of the 1884 Law and the inherent bureaucracy<br />

often delayed excavation permits for almost a year. 11 Foreign excavators who<br />

previously had unregulated access to the finds from their forays into the field were<br />

extremely dissatisfied with the new provision that all artefacts had to be vetted by<br />

the Imperial Museum in Constantinople prior to study and/or analysis. 12 In an effort<br />

to curb the loss of cultural heritage from the empire, Chapter I Article 8 of the 1884<br />

Law specifically prohibited the exporting of artefacts without the permission of the<br />

Imperial Museum. Even with this provision, many foreign archaeological missions<br />

and locals transgressed the law almost immediately after its enactment. 13 A complex<br />

smuggling network, which included Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, developed<br />

and continued through the Mandate period until today.<br />

[ 24 ] FEATURES The Trade in Palestinian Antiquities

At the turn of the early 20 th century the character of archaeological work in the region<br />

underwent a methodological revolution with the beginning of stratigraphic excavations<br />

at some of the most prominent tells in the region. Simultaneously, this period saw the<br />

decline and collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of competition for territory<br />

by the various European nations with vested economic and political interests in the<br />

area. The region comprising modern Israel and Palestine was ceded to the British after<br />

World War I and in June 1922 the League of Nations passed The Palestine Mandate of<br />

the League of Nations. The Mandate for Palestine was an explicit document regarding<br />

Britain’s responsibilities and powers of administration in Palestine including:<br />

“securing the establishment of the Jewish national home”, and “safeguarding the civil<br />

and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine”. 14 The British Mandate period,<br />

often referred to as the ‘Golden Age of Archaeology’ 15 , saw the establishment of an<br />

efficient, centralized colonial government and the improvement of transportation and<br />

communications throughout the region, as it became one of the most active centres of<br />

excavation and archaeological research in the world.<br />

Mandate Legislation<br />

The British Mandate is conventionally seen as a separate period in the general and<br />

legal history of Israel and Palestine. Prior to 1917, Palestine did not exist as a political<br />

or administrative unit but was simply part of the greater Ottoman territory. The League<br />

of Nations granted Mandate territories to the Western powers, which were to serve<br />

as trustees, usually for a limited period of time, with the eventual aim of establishing<br />

self-rule for the locals. 16 As trustees, the Mandate authority was charged with oversight<br />

and protection of the cultural heritage of its territories. In one of its first actions, the<br />

British Mandate government promulgated an Antiquities Proclamation in 1918, which<br />

noted the importance of the region’s cultural heritage. In July of 1920, the Mandate<br />

civil administration took over from the military and a Department of Antiquities<br />

(DOA) was established with the objective of overseeing archaeology in the region.<br />

With the enactment of the Antiquities Proclamation of 1918, archaeology and specific<br />

archaeological sites took on a much more professional and bureaucratic legal status<br />

superseding any religious or magical significance previously imbued through centuries<br />

of pilgrimage. The British oversaw the establishment of the Palestine Archaeological<br />

Museum 17 –built to house the administration of the DOA, public galleries, the archives,<br />

a library, and to serve as a repository of the archaeological riches of the area. 18<br />

Archaeologist John Garstang was appointed as the Director of the Department of<br />

Antiquities for Palestine. As one of his first tasks as director, Garstang formulated<br />

an Antiquities Ordinance for Palestine (AO 1920). In a report of his activities to the<br />

Palestine Exploration Fund, Garstang 19 stated that “the Antiquities Ordinance was<br />

based not only on the collective advice of archaeological and legal specialists, but<br />

embodied the results of experience in neighbouring countries.” By using the 1884<br />

Ottoman Law of Antiquities and the legislative efforts of the surrounding nations<br />

<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 33 [ 25 ]

as a springboard, and in consultation with archaeologists and government officials,<br />

Garstang established an antiquities ordinance vesting the ownership of moveable and<br />

immoveable cultural heritage in the Civil Government of Palestine. The enactment<br />

of this ordinance ensured that the protection and oversight of cultural heritage in<br />

Palestine was carried out locally rather than from a colonial capital.<br />

The primary goal of the AO 1920 was the protection of archaeological antiquities 20<br />

and sites. The regulation of ongoing archaeological excavations was monitored by<br />

the Department of Antiquities, as was the sale of artefacts. In response to criticisms<br />

of the earlier 1884 Law by archaeologists and tourists regarding the lack of access to<br />

archaeological material, a provision was included for the sale of material deemed not<br />

required for the national repository–a decision to be made by the director of the DOA<br />

and its advisory board. The department was given permission by the High Commission<br />

to issue licenses for the trade in antiquities. In 1920, for the first time, a licensed trade<br />

in antiquities was regulated and overseen by a bureaucratic entity–the Department of<br />

Antiquities. Article 21 of The Palestine Mandate of the League of Nations of 1922<br />

further cemented the right to scientific access for nationals and foreigners by insuring<br />