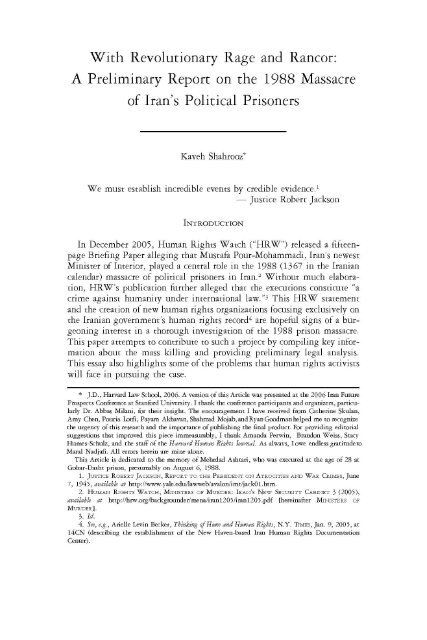

With Revolutionary Rage and Rancor: A Preliminary Report on the ...

With Revolutionary Rage and Rancor: A Preliminary Report on the ...

With Revolutionary Rage and Rancor: A Preliminary Report on the ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

228 Harvard Human Rights Journal / Vol. 20<br />

The gross violati<strong>on</strong>s of human rights in Iran since <strong>the</strong> 1979 Revoluti<strong>on</strong><br />

have been documented in great detail. However, for reas<strong>on</strong>s that remain<br />

largely unexplored, 5 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> are well bey<strong>on</strong>d <strong>the</strong> scope of this paper, <strong>the</strong> Iranian<br />

government has been successful in keeping <strong>on</strong>e of its worst atrocities a secret<br />

from <strong>the</strong> internati<strong>on</strong>al community. During <strong>the</strong> summer of 1988,<br />

shortly after accepting a cease-fire in its eight-year war with Iraq, <strong>the</strong> Iranian<br />

government established informal commissi<strong>on</strong>s to re-try political pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

across <strong>the</strong> country, ordering <strong>the</strong> immediate executi<strong>on</strong> of thous<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

found guilty at <strong>the</strong>se “trials.” The secret executi<strong>on</strong>s were carried out with a<br />

speed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ferocity that surpassed even <strong>the</strong> reign of terror immediately following<br />

<strong>the</strong> Iranian Revoluti<strong>on</strong>. And yet “[t]he curtain of secrecy” surrounding<br />

<strong>the</strong>se executi<strong>on</strong>s was so effective “that no Western journalist<br />

heard of it <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> no Western academic discussed it. They still have not.” 6<br />

5. An unlikely <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> unsatisfying explanati<strong>on</strong> is provided by Joe Stork, HRW’s Middle East <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

North Africa Deputy Director: “At <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> Iran-Iraq war, <strong>the</strong>re was a certain interest in <strong>the</strong> part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> major powers not to stir up <strong>the</strong> pot <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> antag<strong>on</strong>ize Iran.” Ver<strong>on</strong>ique Mistiaen, Memories of a<br />

Slaughter in Iran, TORONTO STAR, Sept. 5, 2004, at F5. Though Stork may be right in his assessment of<br />

why “major powers” did not pursue <strong>the</strong> issue, his explanati<strong>on</strong> reveals little about why human rights<br />

organizati<strong>on</strong>s, including his own, have been largely silent <strong>on</strong> what is arguably <strong>the</strong> single largest government-sp<strong>on</strong>sored<br />

massacre of citizens in c<strong>on</strong>temporary Iranian history. For example, HRW’s MINISTERS<br />

OF MURDER, supra note 2, is <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly HRW publicati<strong>on</strong> to refer to <strong>the</strong> 1988 massacre. Even <strong>the</strong>re,<br />

HRW does not analyze <strong>the</strong> gruesome <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> systematic killing in any depth. A more plausible explanati<strong>on</strong><br />

for <strong>the</strong> reluctance of human rights organizati<strong>on</strong>s to pursue <strong>the</strong> story may be <strong>the</strong> general unpopularity of<br />

<strong>the</strong> political party whose members were <strong>the</strong> primary victims of <strong>the</strong> massacre. The Sazman-e Mojahedin-e<br />

Khalq-e Iran (<strong>the</strong> People’s Mojahedin Organizati<strong>on</strong> of Iran) (“Mojahedin”) enjoyed immense popular support<br />

in <strong>the</strong> early 1980s as Iran’s most powerful oppositi<strong>on</strong> group. The party’s popularity <strong>the</strong>n declined<br />

rapidly as a result of <strong>the</strong> disastrous political decisi<strong>on</strong> to establish military camps in Iraq during <strong>the</strong> Iran-<br />

Iraq war, <strong>the</strong> foolhardy military acti<strong>on</strong>s taken against <strong>the</strong> Iranian government, <strong>the</strong> popular belief (encouraged<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Iranian government’s propag<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>a) that <strong>the</strong> organizati<strong>on</strong> engaged in terrorist acti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

against civilians, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> cult of pers<strong>on</strong>ality developed around <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin’s leaders. See ERVAND<br />

ABRAHAMIAN, THE IRANIAN MOJAHEDIN 243–61 (1989); HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, NO EXIT: HUMAN<br />

RIGHTS ABUSES INSIDE THE MKO CAMPS 5–11 (2005), available at http://hrw.org/backgrounder/mena/<br />

iran0505/iran0505.pdf; Human Rights Watch, Statement <strong>on</strong> Resp<strong>on</strong>ses to Human Rights Watch <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>on</strong> Abuses by <strong>the</strong> Mujahedin-e Khalq Organizati<strong>on</strong> (MKO) (Feb. 15, 2006), http://hrw.org/mideast/<br />

pdf/iran021506.pdf; see also Elizabeth Rubin, The Cult of Rajavi, N.Y. TIMES (MAG.), July 13, 2003, at<br />

26:<br />

Meanwhile, inside Iran, <strong>the</strong> street protesters risking <strong>the</strong>ir lives <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> disappearing inside <strong>the</strong><br />

regime’s pris<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>sider <strong>the</strong> Mujahedeen a plague—as toxic, if not more so, than <strong>the</strong> ruling<br />

clerics. After all, <strong>the</strong> Rajavis sold out <strong>the</strong>ir fellow Iranians to Saddam Hussein, trading intelligence<br />

about <strong>the</strong>ir home country for a place to house <strong>the</strong>ir Marxist-Islamist Rajavi sect.<br />

While Mujahedeen press releases were pouring out last m<strong>on</strong>th, taking undue credit for <strong>the</strong><br />

nightly dem<strong>on</strong>strati<strong>on</strong>s, many antigovernment Iranians were rejoicing over <strong>the</strong> arrest of<br />

Maryam Rajavi <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> w<strong>on</strong>dering where Massoud was hiding <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> why he, too, hadn’t been<br />

apprehended. This past winter in Iran, when such a popular outburst am<strong>on</strong>g students <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs was still just a dream, if you menti<strong>on</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> Mujahedeen, those who knew <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

remembered <strong>the</strong> group laughed at <strong>the</strong> noti<strong>on</strong> of it spearheading a democracy movement.<br />

Instead, <strong>the</strong>y said, <strong>the</strong> Rajavis, given <strong>the</strong> chance, would have been <strong>the</strong> Pol Pot of Iran.<br />

6. ERVAND ABRAHAMIAN, TORTURED CONFESSIONS: PRISONS AND PUBLIC RECANTATIONS IN MOD-<br />

ERN IRAN 210 (1999). Although several years have passed since <strong>the</strong> publicati<strong>on</strong> of Professor<br />

Abrahamian’s chapter <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1988 killings, Western journalists <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> academics have still not produced<br />

much writing <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> research <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> slaughter. In producing this Article, this author estimates that he has<br />

found no more than ten or fifteen English-language news reports of <strong>the</strong> massacre <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>ly a h<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ful of<br />

book chapters addressing <strong>the</strong> topic.

2007 / <str<strong>on</strong>g>With</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rage</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rancor</str<strong>on</strong>g> 229<br />

This Article is an advocacy document intended to familiarize human<br />

rights defenders with <strong>the</strong> 1988 case <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> to encourage <strong>the</strong>m to begin an indepth<br />

investigati<strong>on</strong>. All facts collected for this retelling of <strong>the</strong> 1988 story<br />

are available in <strong>the</strong> public domain, though <strong>the</strong>ir ga<strong>the</strong>ring has required<br />

substantial effort. The sources include memoirs of political figures, memoirs<br />

by pris<strong>on</strong>ers, a h<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ful of human rights reports, brief statements by United<br />

Nati<strong>on</strong>s (“U.N.”) Special Representatives, scholarly essays, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> sporadic<br />

news reports of varying quality <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> credibility from <strong>the</strong> political groups<br />

whose members faced executi<strong>on</strong> in Iranian pris<strong>on</strong>s. For <strong>the</strong> purposes of this<br />

Article, no witnesses, survivors, family members, or government officials<br />

have been interviewed. Undoubtedly, any future investigati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> 1988<br />

massacre will require locating <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> interviewing <strong>the</strong> (few) survivors of <strong>the</strong><br />

massacre <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> (numerous) bereaved family members, both inside <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

outside Iran. However, as I will discuss later, a meaningful legal investigati<strong>on</strong><br />

of <strong>the</strong> 1988 crimes cannot rest <strong>on</strong> such interviews al<strong>on</strong>e. 7 A thorough<br />

legal analysis will also require inside knowledge about Iran’s chain of comm<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

so as to answer central questi<strong>on</strong>s about individual resp<strong>on</strong>sibility<br />

within <strong>the</strong> governmental structure.<br />

Part I of this Article attempts to present a coherent narrative of <strong>the</strong> brutality<br />

unleashed in Iran during <strong>the</strong> summer of 1988, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> briefly discusses<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> possible motivati<strong>on</strong>s behind <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong>s. Although accurate<br />

reporting <strong>on</strong> a secret massacre of nearly two decades ago is difficult, <strong>the</strong><br />

recent publicati<strong>on</strong> of memoirs by former political pris<strong>on</strong>ers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> by Gr<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Ayatollah Hussein Ali M<strong>on</strong>tazeri has greatly facilitated <strong>the</strong> task of investigating<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1988 killing. The dissident Ayatollah M<strong>on</strong>tazeri—Ayatollah<br />

Khomeini’s designated successor prior to a well-publicized forced resignati<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> house arrest (likely motivated by his oppositi<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> 1988 massacre)<br />

8 —provides a wealth of details <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> documents about <strong>the</strong> massacre.<br />

M<strong>on</strong>tazeri’s informati<strong>on</strong> is invaluable in rec<strong>on</strong>structing what occurred in<br />

Iranian pris<strong>on</strong>s in 1988.<br />

In Part II, I apply settled customary internati<strong>on</strong>al law to show that <strong>the</strong><br />

evidence str<strong>on</strong>gly supports HRW’s categorizati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> 1988 massacre as a<br />

crime against humanity. In this regard, I also discuss <strong>the</strong> relevance of <strong>the</strong><br />

legal doctrines surrounding individual criminal resp<strong>on</strong>sibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> comm<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

resp<strong>on</strong>sibility. Finally, Part III outlines some problems human rights<br />

defenders will face in investigating <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> explores <strong>the</strong> reas<strong>on</strong>s<br />

7. See infra Part III.<br />

8. Iranian Authorities Said to be “Jamming” Dissident Ayatollah’s Website, BBC WORLDWIDE MONITOR-<br />

ING, Dec. 24, 2000 (“A chapter, <strong>on</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> most important of <strong>the</strong> memoir’s, addresses <strong>the</strong> underlying<br />

reas<strong>on</strong>s for M<strong>on</strong>tazeri’s fallout with his mentor <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> friend Khomeyni <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> run-up to his ouster. One<br />

of <strong>the</strong> most important of <strong>the</strong> reas<strong>on</strong>s was M<strong>on</strong>tazeri’s staunch oppositi<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong> of thous<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

of <strong>the</strong> opp<strong>on</strong>ents, particularly those who had been sentenced to death <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong>n ordered executed by<br />

Khomeyni in <strong>the</strong> aftermath of <strong>the</strong> Mersad operati<strong>on</strong> mounted against units of Mojahedin-e Khalq that<br />

had penetrated a few kilometers inside Iran from Iraq.”) (citing AL-SHARQ AL-AWSAT (L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>), Dec.<br />

14, 2000).

230 Harvard Human Rights Journal / Vol. 20<br />

why, despite <strong>the</strong>se difficulties, <strong>the</strong> massacre still matters. I argue that despite<br />

<strong>the</strong> general indifference shown by most human rights organizati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

an investigati<strong>on</strong> ought to be pursued vigorously <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> immediately. A proper<br />

accounting for 1988 is important to survivors <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> families of victims, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is<br />

an important step in <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>going struggle for democracy <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> human rights<br />

in Iran.<br />

I. A SUMMER MASSACRE<br />

A. The Military <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Political C<strong>on</strong>text<br />

If you think that <strong>on</strong>e day you’ll be freed from pris<strong>on</strong> like heroes,<br />

you’re dead wr<strong>on</strong>g. 9<br />

— Assadollah Lajevardi, Director of Evin Pris<strong>on</strong><br />

On July 18, 1988, <strong>on</strong>e year after <strong>the</strong> U.N. Security Council issued a<br />

peace proposal for <strong>the</strong> Iran-Iraq war, Iran abruptly reversed its previously<br />

defiant positi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> unc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>ally accepted <strong>the</strong> cease-fire in Resoluti<strong>on</strong><br />

598. 10 The severe defeats of Iranian forces in <strong>the</strong> final year of fighting had<br />

led Western analysts to assert that “Iran can no l<strong>on</strong>ger fight without risking<br />

a collapse of its ec<strong>on</strong>omy <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, indeed, its revoluti<strong>on</strong>.” 11 Most Iranians<br />

learned of <strong>the</strong> cease-fire from state radio, which broadcast <strong>the</strong> now-famous<br />

announcement by Ayatollah Khomeini comparing <strong>the</strong> acceptance of Resoluti<strong>on</strong><br />

598 to “swallowing pois<strong>on</strong>.” 12 The news prompted both jubilati<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> debate across <strong>the</strong> country, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> nowhere more passi<strong>on</strong>ately than in pris<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

where pris<strong>on</strong>ers communicated across wards by tapping Morse code <strong>on</strong><br />

pris<strong>on</strong> walls. 13 Though some remained deeply doubtful, many political pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

celebrated <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> destructive war <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> interpreted Khomeini’s<br />

announcement as indicative of a forthcoming liberalizati<strong>on</strong>. 14 Nima<br />

Parvaresh, <strong>the</strong>n a pris<strong>on</strong>er in Gohar-Dasht pris<strong>on</strong>, 40 kilometers outside of<br />

Tehran, recalls <strong>the</strong> speculati<strong>on</strong> am<strong>on</strong>g his cellmates:<br />

Am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers in <strong>the</strong> ward, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> even when communicating<br />

with o<strong>the</strong>r wards, <strong>the</strong>re was much talk. Many pris<strong>on</strong>ers assessed<br />

<strong>the</strong> events as a major crisis in <strong>the</strong> government <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> as a result of a<br />

9. J<strong>on</strong>o<strong>on</strong>e Koshtar, Dar Roozhaye Ghatle Ame Zendanyane Siyasi [The Madness of Mass Killing, in <strong>the</strong><br />

Days of <strong>the</strong> Massacre of Political Pris<strong>on</strong>ers], 64 RAHE TUDEH 7, 11 (1997).<br />

10. Iran Says It Accepts Year-Old U.N. Call for Ceasefire in War, L.A. TIMES, July 18, 1988, at A2.<br />

11. Youssef M. Ibrahim, Khomeini Accepts ‘Pois<strong>on</strong>’ of Ending <strong>the</strong> War with Iraq; Bitter Defeat for Ayatollah,<br />

N.Y. TIMES, July 21, 1988, at A1.<br />

12. Edward Cody, Khomeini Says Ceasefire Decisi<strong>on</strong> His; Reversal of L<strong>on</strong>g-Held Positi<strong>on</strong> “Deadlier Than<br />

Swallowing Pois<strong>on</strong>,” WASH. POST, July 21, 1988, at A1 (“‘Making this decisi<strong>on</strong> was deadlier than swallowing<br />

pois<strong>on</strong>,’ Khomeini said at ano<strong>the</strong>r point. ‘I submit myself to God’s will <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> drank this drink for<br />

His satisfacti<strong>on</strong>.’”).<br />

13. Nima Parvaresh, Talkh, Na Hamch<strong>on</strong> Hameyeh Talkheeha [Bitter, Unlike Any O<strong>the</strong>r Bitterness], 14<br />

CHESHMANDAZ 62, 64 (1994).<br />

14. NIMA PARVARESH, NABARDI NABARABAR: GOZARESHI AZ HAFT SAL ZENDAN 1361–68 [AN<br />

UNEQUAL BATTLE: A REPORT OF SEVEN YEARS IN PRISON 1982–1989] 106 (1995).

2007 / <str<strong>on</strong>g>With</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rage</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rancor</str<strong>on</strong>g> 231<br />

mass movement protesting against <strong>the</strong> government. They anticipated<br />

even fur<strong>the</strong>r changes; at least a move from <strong>the</strong> government’s<br />

direct fascist oppressi<strong>on</strong> to a more liberal policy. 15<br />

The pris<strong>on</strong>ers’ optimism was not unjustified, likely inspired by <strong>the</strong> relative<br />

calm that had pervaded Iranian pris<strong>on</strong>s between 1984 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> early 1988.<br />

Supporters of <strong>the</strong> moderate Ayatollah M<strong>on</strong>tazeri had temporarily wrestled<br />

c<strong>on</strong>trol of Iran’s pris<strong>on</strong>s 16 away from hardliners like Assadollah Lajevardi<br />

(famous am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> oppositi<strong>on</strong> as “The Butcher of Evin”). 17 The pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

note that, until shortly before M<strong>on</strong>tazeri’s supporters were sidelined <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong><br />

mass executi<strong>on</strong>s began, <strong>the</strong> atmosphere of <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>s was sufficiently calm<br />

for <strong>the</strong>m to dem<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>cessi<strong>on</strong>s from <strong>the</strong> authorities. 18 Some even note that<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>ers launched hunger strikes to protest insufficient pris<strong>on</strong> meals. 19<br />

Whatever <strong>the</strong> prevalent mood in pris<strong>on</strong>s immediately after Iran’s acceptance<br />

of <strong>the</strong> cease-fire, <strong>the</strong> situati<strong>on</strong> changed dramatically after Artesh-e<br />

Azadibakhsh-e Melli-e Iran (<strong>the</strong> Nati<strong>on</strong>al Liberati<strong>on</strong> Army of Iran), <strong>the</strong> military<br />

wing of <strong>the</strong> oppositi<strong>on</strong> Sazman-e Mojahedin-e Khalq-e Iran (<strong>the</strong> People’s<br />

15. Id.<br />

16. Maziar Behrooz, Reflecti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> Iran’s Pris<strong>on</strong> System During <strong>the</strong> M<strong>on</strong>tazeri Years (1985–1988), 2<br />

IRAN ANALYSIS Q. 11 (2005), available at http://web.mit.edu/isg/IAQWinter05.pdf; REZA AFSHARI,<br />

HUMAN RIGHTS IN IRAN: THE ABUSE OF CULTURAL RELATIVISM 105 (2001). For a brief account of<br />

M<strong>on</strong>tazeri’s general c<strong>on</strong>flict with <strong>the</strong> Iranian establishment, see BAQER MOIN, KHOMEINI: LIFE OF THE<br />

AYATOLLAH 277–84 (1999).<br />

17. Lajevardi’s reputati<strong>on</strong> as <strong>the</strong> “Butcher of Evin” seems to have been well deserved. According to<br />

a 1989 report published in <strong>the</strong> Guardian newspaper:<br />

[Lajevardi] is especially remembered for two widely used innovati<strong>on</strong>s in Iranian gaols.<br />

The first, still in operati<strong>on</strong> was <strong>the</strong> rape of virgin girls through forced ‘marriages’ to pris<strong>on</strong><br />

guards, so that an obscure religious sancti<strong>on</strong> against <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong> of virgins could be<br />

overcome.<br />

The sec<strong>on</strong>d, now apparently obsolete or used <strong>on</strong>ly with great care, was to test ‘c<strong>on</strong>verted’<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>ers’ loyalty by using <strong>the</strong>m in firing squads aiming at o<strong>the</strong>r inmates.<br />

This ploy backfired when ‘tested’ inmates opened fire <strong>on</strong> pris<strong>on</strong> officials including Ladjevardi<br />

himself, before committing suicide.<br />

Farhad Mogaddam, Death Comes to an Iranian Dissident: A Young Woman’s Fruitless Struggle to Stay Alive<br />

Under Ayatollah Khomeini, GUARDIAN (L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>), Jan. 13, 1989.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> tenth anniversary of <strong>the</strong> 1988 massacre, Mojahedin agents assassinated Assadollah Lajevardi.<br />

Iran: Double St<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ard?, ECONOMIST, Aug. 29, 1998, at 45 (“On August 23rd, Assod-ollah La-je-vardi<br />

was shot dead by two men in his tailor’s shop in Tehran’s bazaar. The Iraq-based [Mojahedin] immediately,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> proudly, claimed resp<strong>on</strong>sibility.”).<br />

18. See AFSHARI, supra note 16, at 108, 113; see also Witness to Massacre: Interview with M<strong>on</strong>ireh<br />

Baradaran, IRAN BULL., available at http://www.iran-bulletin.org/witness/MONIREH1.html (last visited<br />

Dec. 22, 2006) [hereinafter Interview with M<strong>on</strong>ireh Baradaran].<br />

19. Interview with M<strong>on</strong>ireh Baradaran, supra note 18; see also SAZMAN-E MOJAHEDIN-E KHALQ-E<br />

IRAN, GHATLE-AME ZENDANYANE SIYASI [THE MASSACRE OF POLITICAL PRISONERS] 191 (1999) (“The<br />

3rd <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5th wards in Evin became famous because of <strong>the</strong>ir launch of several successful hunger strikes in<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>.”). Such hunger strikes still entailed significant risks for political pris<strong>on</strong>ers after <strong>the</strong> hardliners<br />

managed to regain c<strong>on</strong>trol of <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>s. Amnesty Internati<strong>on</strong>al noted that it had received a report of<br />

“a group of 40 political pris<strong>on</strong>ers executed in early 1987 for taking part in a hunger-strike to protest<br />

about c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s in Evin pris<strong>on</strong>.” AMNESTY INT’L, IRAN, VIOLATIONS OF HUMAN RIGHTS 1987–1990,<br />

11 (1990) [hereinafter AMNESTY INT’L REPORT].

232 Harvard Human Rights Journal / Vol. 20<br />

Mojahedin Organizati<strong>on</strong> of Iran) (“Mojahedin”), 20 launched an armed incursi<strong>on</strong><br />

into western Iran from its bases in Iraq. The Mojahedin—an Islamic-<br />

Marxist political organizati<strong>on</strong> that had initially supported <strong>the</strong> Iranian<br />

Revoluti<strong>on</strong>, but violently split from Ayatollah Khomeini in <strong>the</strong> early<br />

1980’s due to intense ideological disagreements—likely interpreted Iran’s<br />

acceptance of Resoluti<strong>on</strong> 598 as a sign that <strong>the</strong> government was crumbling.<br />

Thus, <strong>the</strong>y began “Operati<strong>on</strong> Eternal Light” <strong>on</strong> July 25, 1988, shortly after<br />

<strong>the</strong> announcement of <strong>the</strong> cease-fire. 21 Iranian military forces quickly repelled<br />

<strong>the</strong> ill-c<strong>on</strong>ceived <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> poorly executed attack, h<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ing <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin<br />

a severe defeat that U.S. officials characterized as a “shellacking.” 22 <str<strong>on</strong>g>With</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>the</strong> informati<strong>on</strong> currently available, it is difficult to establish whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong><br />

Mojahedin attack was, in fact, <strong>the</strong> real reas<strong>on</strong> behind <strong>the</strong> decisi<strong>on</strong> to execute<br />

Iran’s political pris<strong>on</strong>ers. What is known, however, is that immediately after<br />

learning of <strong>the</strong> incursi<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>s entered an unusual state of emergency,<br />

so<strong>on</strong> after which <strong>the</strong> killings began. 23 Pris<strong>on</strong>ers affiliated with <strong>the</strong><br />

Mojahedin bore <strong>the</strong> brunt of <strong>the</strong> government’s massacre.<br />

B. The Mass Executi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

In <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong>re are always people who can’t be dealt with in<br />

any way but through repressi<strong>on</strong>. We must repress those people.<br />

This atmosphere of terror must exist for such traitors <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> deceitful<br />

people. 24<br />

— Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Iran’s Former President<br />

Most examinati<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> massacre begin <strong>the</strong> narrative in mid-July 1988,<br />

when “<strong>the</strong> regime suddenly, without warning, isolated <strong>the</strong> main pris<strong>on</strong>s<br />

20. “Sazman-e Mojahedin-e Khalq-e Iran” is <strong>the</strong> official, Persian-language name of <strong>the</strong> organizati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> English-language press, various terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> acr<strong>on</strong>yms are used to denote <strong>the</strong> group. Writers<br />

sometimes refer to <strong>the</strong> organizati<strong>on</strong> simply as <strong>the</strong> “Mojahedin,” which reflects what <strong>the</strong> group is called<br />

by most Iranians. O<strong>the</strong>rs use <strong>the</strong> acr<strong>on</strong>ym “PMOI,” derived from <strong>the</strong> direct translati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> group’s<br />

name: “The People’s Mojahedin Organizati<strong>on</strong> of Iran.” Still o<strong>the</strong>rs use MKO (Mojahedin Khalq Organizati<strong>on</strong>),<br />

or MEK (Mojahedin-E Khalq). The name of <strong>the</strong> group is also transliterated differently in various<br />

texts. In this Article <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> in <strong>the</strong> footnotes, I use <strong>the</strong> terms “Mojahedin” <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> “PMOI,” because <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

<strong>the</strong> names by which <strong>the</strong> group refers to itself. However, where citing from o<strong>the</strong>r sources, I use acr<strong>on</strong>yms<br />

found in <strong>the</strong> original.<br />

Erv<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Abrahamian notes that <strong>the</strong> term “Mojahed” (<strong>the</strong> singular form of “Mojahedin”), which<br />

literally means ‘holy warrior,’ was originally used to describe <strong>the</strong> armed compani<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong><br />

Prophet Mohammad. In adopting <strong>the</strong>ir title, <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin were influenced in part by religious<br />

sentiments <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> images of <strong>the</strong>se early crusaders. They also were influenced, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> to a<br />

greater extent, by <strong>the</strong> fact that this was <strong>the</strong> label used by <strong>the</strong> Algerian revoluti<strong>on</strong>aries <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> by<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> armed volunteers in <strong>the</strong> Iranian Revoluti<strong>on</strong> of 1905–1911.<br />

ABRAHAMIAN, supra note 6, at 4. For an in-depth study <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin, see id.<br />

21. David Wood, Anti-Khomeini Rebels Drive Deep into Iran, THE EVENING NEWS HARRISBURG, July<br />

27, 1988; see also Nati<strong>on</strong>al Liberati<strong>on</strong> Army of Iran, Operati<strong>on</strong> Eternal Light, http://www.iran-e-azad.<br />

org/english/nla/etl.html (last visited Jan. 26, 2007).<br />

22. Alladin Touran, Iran Resistance ‘Shellacking’ Untrue, CHI. TRIB., Oct. 1, 1988, at 10.<br />

23. REZA GHAFFARI, KHATERATE YEK ZENDANI AZ ZENDANHAYE JOMHURIYEH ISLAMI [MEMOIRS<br />

OF A PRISONER IN THE PRISONS OF THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC] 237 (1998).<br />

24. Nasser Mohajer, Koshtare Bozorg [The Great Massacre], 57 ARASH 4, 7 (1996).

2007 / <str<strong>on</strong>g>With</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rage</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rancor</str<strong>on</strong>g> 233<br />

from <strong>the</strong> outside world.” 25 Amnesty Internati<strong>on</strong>al reports that “<strong>the</strong> first<br />

sign that something was happening in <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>s came in July 1988 when<br />

family visits to political pris<strong>on</strong>ers were suspended.” 26 Closer analysis of <strong>the</strong><br />

memoirs written by survivors reveals, however, that pris<strong>on</strong> authorities had<br />

begun preparati<strong>on</strong> for <strong>the</strong> massacre m<strong>on</strong>ths before <strong>the</strong> war ended, indicating<br />

that <strong>the</strong> cease-fire <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin attack simply may have been c<strong>on</strong>venient<br />

pretexts to carry out pre-existing plans.<br />

The survivors c<strong>on</strong>sistently note that pris<strong>on</strong> officials took <strong>the</strong> unusual step<br />

in late 1987 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> early 1988 of re-questi<strong>on</strong>ing <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> separating all political<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>ers according to party affiliati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> length of sentence. As an ominous<br />

sign of things to come, pris<strong>on</strong>ers in Gohar-Dasht pris<strong>on</strong> recall being<br />

summ<strong>on</strong>ed from <strong>the</strong>ir wards to face questi<strong>on</strong>ing. 27 Some wore blindfolds<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> process, whereas o<strong>the</strong>rs recall seeing a committee comprised<br />

of prosecutors, pris<strong>on</strong> authorities, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Intelligence Ministry officials assigned<br />

to re-interrogate each individual. 28 Though questi<strong>on</strong>s varied slightly<br />

depending <strong>on</strong> political affiliati<strong>on</strong>, 29 authorities typically asked pris<strong>on</strong>ers <strong>the</strong><br />

following questi<strong>on</strong>s: “Do you still believe in your political group <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> its<br />

ideology?”; “Do you accept <strong>the</strong> legitimacy of <strong>the</strong> Islamic Republic?”; “Do<br />

you pray?”; “Would you be willing to go to <strong>the</strong> fr<strong>on</strong>ts to fight against <strong>the</strong><br />

Iraqis?”; “Would you be willing to publicly c<strong>on</strong>demn your political<br />

group?”; <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> “If you were to be freed, would you be willing to be publicly<br />

interviewed?” 30 In Evin pris<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> “new deputy warden, Hossein-Zadeh,<br />

briefly interviewed each pris<strong>on</strong>er about her/his views. The inquiry c<strong>on</strong>cerned<br />

<strong>the</strong> Islamic Republic, religi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Marxism.” 31<br />

After <strong>the</strong> interrogati<strong>on</strong>s, Mojahedin pris<strong>on</strong>ers, who self-identified as practicing<br />

Muslims, were separated from a<strong>the</strong>ist leftist pris<strong>on</strong>ers. 32 Pris<strong>on</strong> officials<br />

also separated pris<strong>on</strong>ers based <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> length of <strong>the</strong>ir sentences, 33<br />

removing those deemed “trouble-makers” from general wards <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> placing<br />

<strong>the</strong>m in solitary c<strong>on</strong>finement until <strong>the</strong> massacre. 34 As a result of this re-<br />

25. ABRAHAMIAN, supra note 6, at 209.<br />

26. AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra note 19, at 13.<br />

27. GHAFFARI, supra note 23, at 229.<br />

28. Id.<br />

29. At <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>the</strong> vast majority of Iran’s political pris<strong>on</strong>ers were ei<strong>the</strong>r members of <strong>the</strong> ideologically<br />

Islamic-Marxist Mojahedin or members of Socialist <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Communist parties. Most prominent<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> latter groups were <strong>the</strong> Tudeh Party <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> Sazeman-e Fadayian-e Khalq-e Iran (The People’s<br />

Fadayian Organizati<strong>on</strong> of Iran).<br />

30. GHAFFARI, supra note 23, at 234; Mohajer, supra note 24, at 5.<br />

31. AFSHARI, supra note 16, at 108.<br />

32. NAT’L COUNCIL OF RESISTANCE OF IRAN, FOREIGN AFFAIRS COMM., CRIME AGAINST HUMAN-<br />

ITY: INDICT IRAN’S RULING MULLAHS FOR MASSACRE OF 30,000 POLITICAL PRISONERS 69 (2001) [hereinafter<br />

CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY] (<strong>on</strong> file with <strong>the</strong> author); see also PARVARESH, supra note 14, at<br />

99–100.<br />

33. CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY, supra note 32, at 69 (“In Gohar-Dasht pris<strong>on</strong>, those c<strong>on</strong>demned to<br />

life impris<strong>on</strong>ment were transferred to Evin <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> rest were divided into two groups of under- <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

over-ten-year terms.”); PARVARESH, supra note 14, at 99–100.<br />

34. An<strong>on</strong>ymous, Man Shahede Ghatle Ame Zendanyane Siyasi Boodam [I Witnessed <strong>the</strong> Massacre of Political<br />

Pris<strong>on</strong>ers], 14 Cheshm<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>az 67, 68 (1994); PARVARESH, supra note 14, at 102.

234 Harvard Human Rights Journal / Vol. 20<br />

interrogati<strong>on</strong>, a number of pris<strong>on</strong>ers (particularly those sentenced to life<br />

impris<strong>on</strong>ment) moved from Gohar-Dasht to Evin pris<strong>on</strong>. 35 The changes<br />

c<strong>on</strong>fused <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers, who did not underst<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> significance of <strong>the</strong> interrogati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> reshuffling. 36 In retrospect, <strong>the</strong> Iranian government<br />

may have meant to c<strong>on</strong>fuse <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> disrupt communicati<strong>on</strong> networks,<br />

preventing pris<strong>on</strong>ers from warning <strong>on</strong>e ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>on</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> killing began.<br />

Reflecting <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> preparati<strong>on</strong>s that necessarily must have preceded <strong>the</strong><br />

executi<strong>on</strong>s, <strong>on</strong>e pris<strong>on</strong>er notes:<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>With</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong>se new arrangements, all that we had created in our<br />

years of resistance was lost. All <strong>the</strong> communicati<strong>on</strong> [networks]<br />

that had formed as a result of years of experiencing torture <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

executi<strong>on</strong>s were completely destroyed. It was with <strong>the</strong>se arrangements<br />

that Khomeini’s regime prepared itself for <strong>the</strong> creati<strong>on</strong> of a<br />

bloodbath <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> massacre of political pris<strong>on</strong>ers. 37<br />

Although exact dates are difficult to determine, <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong>s in Tehran<br />

likely began <strong>on</strong> July 27, 1988, in Evin, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> July 30 in Gohar-Dasht<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>. 38 The pris<strong>on</strong>ers became completely isolated from <strong>the</strong> outside world<br />

as <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>s moved into emergency mode. Parvaresh recalls that “<strong>on</strong> July<br />

27, 1988, <strong>the</strong> guards took all <strong>the</strong> televisi<strong>on</strong> sets out of <strong>the</strong> wards, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cut<br />

off all <strong>the</strong> loudspeakers that aired radio news <strong>on</strong> 2:00 p.m. <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 8:00 p.m.<br />

From that day <strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> fresh air for all wards was cancelled.” 39 Guards prohibited<br />

ill pris<strong>on</strong>ers from visiting <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong> infirmary. 40 Finally, all family<br />

visits were suspended “until fur<strong>the</strong>r notice.” 41 The first pris<strong>on</strong>ers to be exterminated<br />

were <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin, many of whom had already served several<br />

years of <strong>the</strong>ir sentences. During this time, officials kept left-wing pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

isolated without any idea of <strong>the</strong> horrors unfolding around <strong>the</strong>m. The leftists<br />

originally speculated that Khomeini had died or that a coup d’état or public<br />

rebelli<strong>on</strong> was underway. 42 They were slow to realize that <strong>the</strong> emergency<br />

situati<strong>on</strong> was actually prompted by circumstances inside <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

The leftist pris<strong>on</strong>ers slowly pieced toge<strong>the</strong>r small <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> increasingly macabre<br />

clues. The pris<strong>on</strong>ers heard late-night sounds of marching Pasdars (<str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Guards), stomping <strong>the</strong>ir feet <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> chanting “Death to <strong>the</strong><br />

[Mojahedin]” or “Death to infidels.” 43 Elsewhere, Mojahedin pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

tapped Morse code messages to inform <strong>the</strong> adjacent ward, made up mostly<br />

35. I Witnessed <strong>the</strong> Massacre of Political Pris<strong>on</strong>ers, supra note 34, at 67; GHAFFARI, supra note 23, at<br />

235.<br />

36. AFSHARI, supra note 16, at 108.<br />

37. GHAFFARI, supra note 23, at 235.<br />

38. CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY, supra note 32, at 71–72.<br />

39. PARVARESH, supra note 14, at 109; J<strong>on</strong>o<strong>on</strong>e Koshtar, supra note 9, at 8.<br />

40. J<strong>on</strong>o<strong>on</strong>e Koshtar, supra note 9, at 8.<br />

41. 3 MONIREH BARADARAN (RAHA M.), HAGHIGHATE SADEH [SIMPLE TRUTHS] 386 (2000).<br />

42. An<strong>on</strong>ymous, Roozhayeh Ghor-eh Barayeh Edam [Days of <strong>the</strong> Executi<strong>on</strong> Lottery], 65 RAHE TUDEH<br />

14, 15 (1997).<br />

43. BARADARAN, supra note 41, at 388.

2007 / <str<strong>on</strong>g>With</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rage</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rancor</str<strong>on</strong>g> 235<br />

of Communists, that 200 of <strong>the</strong>ir members had been executed that day. 44<br />

Years of growing mistrust between pris<strong>on</strong>ers of different political stripes,<br />

however, meant that many of <strong>the</strong> Communists dismissed this story as a<br />

rumor. 45 Reza Ghaffari, a former pris<strong>on</strong>er, writes:<br />

Some<strong>on</strong>e sent a message using Morse code that many of <strong>the</strong><br />

Mojahedin pris<strong>on</strong>ers had been hanged. I could not believe it. I<br />

thought that <strong>the</strong> authorities were spreading rumors to frighten<br />

<strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> to break <strong>the</strong>ir spirit. A message was sent from<br />

our ward that maybe <strong>the</strong> police, itself, spread <strong>the</strong> news of executi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

to break <strong>the</strong> will of resistant pris<strong>on</strong>ers. 46<br />

Over time, <strong>the</strong> signs of an exterminati<strong>on</strong> campaign became clear. A survivor<br />

remembers an Afghan pris<strong>on</strong> worker who tried to warn <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

by miming a noose around his neck, a gesture misinterpreted to mean that<br />

Khomeini had died. 47 The pris<strong>on</strong>ers in Ward 7 of Gohar-Dasht saw Davood<br />

Lashgari, <strong>on</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> more powerful wardens of that pris<strong>on</strong>, carrying thick<br />

rope to <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong> auditorium. 48 Pris<strong>on</strong>ers vividly recall witnessing guards<br />

carry dead bodies to trucks in <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong> yard. 49 Yet <strong>the</strong>y found <strong>the</strong> prospect<br />

of a large-scale massacre so unbelievable that <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers simply assumed<br />

<strong>the</strong> bodies to be those of Mojahedin soldiers killed during <strong>the</strong> recent border<br />

skirmish. 50 Some in Gohar-Dasht saw guards with facemasks entering <strong>the</strong><br />

pris<strong>on</strong> amphi<strong>the</strong>ater; <strong>the</strong>y would later learn that <strong>the</strong> morgue freezers had<br />

broken down. 51 When some Communist pris<strong>on</strong>ers finally asked Davood<br />

Lashgari about <strong>the</strong> masked guards entering <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong> auditorium <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong><br />

repulsive odor emanating from within, <strong>the</strong> warden told <strong>the</strong>m: “The septic<br />

tank in <strong>the</strong> amphi<strong>the</strong>ater is broken <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is being repaired. D<strong>on</strong>’t your comrades<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Soviet Uni<strong>on</strong> sometimes clean out <strong>the</strong>ir pris<strong>on</strong>s too?” 52 The<br />

double entendre was likely not lost <strong>on</strong> nervous pris<strong>on</strong>ers slowly becoming<br />

aware of <strong>the</strong> brutality awaiting <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

The first <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> primary targets of <strong>the</strong> 1988 massacre were supporters of <strong>the</strong><br />

Mojahedin. 53 According to Amnesty Internati<strong>on</strong>al, many of those Mojahedin<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>ers “had been tried <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> sentenced to pris<strong>on</strong> terms during <strong>the</strong> early<br />

1980s, many for n<strong>on</strong>-violent offences such as distributing newspapers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

44. Days of <strong>the</strong> Executi<strong>on</strong> Lottery, supra note 42, at 15.<br />

45. Id.; see also Parvaresh, supra note 13, at 65 (“The news spread across <strong>the</strong> ward. The majority of<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>ers were skeptical because, until <strong>the</strong>n, <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin pris<strong>on</strong>ers had repeatedly spread false news<br />

about <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong>ir members. We all interpreted <strong>the</strong> message as a c<strong>on</strong>tinuati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> same<br />

false news.”).<br />

46. GHAFFARI, supra note 23, at 240.<br />

47. I Witnessed <strong>the</strong> Massacre of Political Pris<strong>on</strong>ers, supra note 34, at 70.<br />

48. Mohajer, supra note 24, at 6.<br />

49. Id.<br />

50. PARVARESH, supra note 14, at 109.<br />

51. ABRAHAMIAN, supra note 6, at 211.<br />

52. I Witnessed <strong>the</strong> Massacre of Political Pris<strong>on</strong>ers, supra note 34, at 70.<br />

53. GHAFFARI, supra note 23, at 242.

236 Harvard Human Rights Journal / Vol. 20<br />

leaflets, taking part in dem<strong>on</strong>strati<strong>on</strong>s or collecting funds for pris<strong>on</strong>ers’<br />

families.” 54 In pris<strong>on</strong>s across Iran, officials removed Mojahedin pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

from <strong>the</strong>ir cells <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> told <strong>the</strong>m that an amnesty commissi<strong>on</strong> would be meeting<br />

with <strong>the</strong>m individually. 55 Officials <strong>the</strong>n forced <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers to line up<br />

blindfolded <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> wait, often for hours, before individually being brought<br />

before a tribunal comprised of three to twelve members. 56<br />

The group that <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers faced, which came later to be known widely<br />

as <strong>the</strong> “Death Commissi<strong>on</strong>,” was not in fact an amnesty commissi<strong>on</strong>. Its<br />

sole purpose was to re-try each pris<strong>on</strong>er <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> order <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong> of those<br />

remaining steadfast in <strong>the</strong>ir oppositi<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> government. What took place<br />

before <strong>the</strong>se commissi<strong>on</strong>s “bore little resemblance to judicial proceedings<br />

aimed at establishing <strong>the</strong> guilt or innocence of a defendant with regard to a<br />

recognized criminal offence under <strong>the</strong> law. Instead, <strong>the</strong>y appear to have<br />

been formalized interrogati<strong>on</strong> sessi<strong>on</strong>s . . .” designed to discover a pris<strong>on</strong>er’s<br />

true political beliefs. 57<br />

The sessi<strong>on</strong>s were very brief, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, in <strong>the</strong> case of Mojahedin pris<strong>on</strong>ers, often<br />

ended after a single, simple questi<strong>on</strong>: that of <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>er’s political affiliati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

All who replied “Mojahedin” would be immediately sentenced to<br />

death. 58 In <strong>the</strong> eyes of <strong>the</strong> Death Commissi<strong>on</strong> judges, <strong>the</strong> “correct” answer<br />

to this preliminary questi<strong>on</strong> was “M<strong>on</strong>afeqin” (“hypocrites”), a pejorative<br />

term <strong>the</strong> Iranian government has l<strong>on</strong>g assigned to <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin organizati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

59 The undesirable answer meant that guards would immediately guide<br />

<strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>er to a line <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> left side of a hallway leading to a room where<br />

<strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>er could write a last will, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> subsequently take him to <strong>the</strong> amphi<strong>the</strong>ater<br />

to hang. 60 The pris<strong>on</strong>ers were hung six at a time, although some<br />

alternate accounts claim that, each half hour, thirty-three pris<strong>on</strong>ers were<br />

hanged using cranes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> forklifts. 61<br />

Pris<strong>on</strong>ers providing <strong>the</strong> “correct” answer to <strong>the</strong> first questi<strong>on</strong> were <strong>the</strong>n<br />

asked <strong>the</strong> following questi<strong>on</strong>s: “Are you willing to give an interview <strong>on</strong><br />

54. AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra note 19, at 13.<br />

55. CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY, supra note 32, at 71; GHAFFARI, supra note 23, at 242–43.<br />

56. Based <strong>on</strong> survivor accounts, <strong>the</strong> number of judges <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>se tribunals was not c<strong>on</strong>stant. I Witnessed<br />

<strong>the</strong> Massacre of Political Pris<strong>on</strong>ers, supra note 34, at 69.<br />

57. AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra note 19, at 16.<br />

58. Id.<br />

59. The word “M<strong>on</strong>afeq” is an Arabic term for “hypocrite.” The term is <strong>the</strong> title of Surah 63 of <strong>the</strong><br />

Koran <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is, thus, <strong>the</strong>ologically significant. In that Surah, <strong>the</strong> following verse appears: “Under <strong>the</strong><br />

guise of <strong>the</strong>ir apparent faith, [<strong>the</strong> hypocrites] repel <strong>the</strong> people from <strong>the</strong> path of Allah. Evil indeed is<br />

what <strong>the</strong>y do.” THE KORAN 63:2. In using <strong>the</strong> term, Iran’s Islamic government implies that <strong>the</strong><br />

Mojahedin’s Islamic ideology is inau<strong>the</strong>ntic <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is used for evil ends. Interestingly, <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>the</strong> word<br />

“M<strong>on</strong>afeqin” <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> its loaded religious subtext did not originate with Iran’s <strong>the</strong>ocratic government. The<br />

secular government of <strong>the</strong> Shah initially used <strong>the</strong> Arabic term. ABRAHAMIAN, supra note 6, at 143–44<br />

(“The [m<strong>on</strong>archist] regime, claiming that <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin were unbelievers masquerading as Muslims,<br />

used <strong>the</strong> Koranic term M<strong>on</strong>afeqin (hypocrites) to describe <strong>the</strong>m—a label that <strong>the</strong> Islamic Republic was<br />

later to use in its own effort to discredit <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin.”).<br />

60. PARVARESH, supra note 14, at 119.<br />

61. Compare ABRAHAMIAN, supra note 6, at 211, with CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY, supra note 32, at<br />

23.

2007 / <str<strong>on</strong>g>With</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rage</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rancor</str<strong>on</strong>g> 237<br />

televisi<strong>on</strong> to c<strong>on</strong>demn <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> expose <strong>the</strong> [M]<strong>on</strong>afeqin?”; “Are you willing to<br />

fight with <strong>the</strong> forces of <strong>the</strong> Islamic Republic against <strong>the</strong> [M]<strong>on</strong>afeqin?”;<br />

“Are you willing to put a noose around <strong>the</strong> neck of an active member of <strong>the</strong><br />

[M]<strong>on</strong>afeqin?”; <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> “Are you willing to clear <strong>the</strong> minefields for <strong>the</strong> army of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Islamic Republic?” 62 An unsatisfactory answer to any of <strong>the</strong>se questi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

meant a death sentence for <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>er. Since <strong>the</strong> purpose of <strong>the</strong> questi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

was to test <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers’ inner beliefs, some judges dem<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ed that pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

prove <strong>the</strong>ir loyalty to <strong>the</strong> government by becoming pris<strong>on</strong> informants.<br />

In a particularly moving passage, Reza Ghaffari recounts <strong>the</strong> story of what<br />

his friend Habib, a member of <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin, suffered during his last<br />

moments:<br />

When [Habib] appeared before <strong>the</strong> Death Commissi<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

asked him about his [affiliati<strong>on</strong>s]. He said ‘M<strong>on</strong>afeqin.’ They<br />

asked him if he was willing to participate in a televised interview<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> to c<strong>on</strong>demn <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> he said that he is willing to<br />

do so. [The judge] asked again if he was willing to sign a petiti<strong>on</strong><br />

against <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin’s leadership. He said that he’s willing. The<br />

[judge’s] last questi<strong>on</strong> to Habib was whe<strong>the</strong>r he is willing to<br />

reveal informati<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong> authorities about five resistant<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>ers, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> to cooperate with [<strong>the</strong>m] by providing intelligence.<br />

But Habib stood firm <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> was unwilling to give in to<br />

such disgrace. He went to <strong>the</strong> gallows. 63<br />

Given how quickly events transpired, very few Mojahedin pris<strong>on</strong>ers actually<br />

survived <strong>the</strong> 1988 killings. Informati<strong>on</strong> about <strong>the</strong> early days of <strong>the</strong> massacre<br />

is c<strong>on</strong>sequently vague at best.<br />

A slightly clearer picture is available for <strong>the</strong> experience of leftist pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

brought before <strong>the</strong> Death Commissi<strong>on</strong>. By <strong>the</strong> time <strong>the</strong> Iranian government<br />

turned its attenti<strong>on</strong> to secular leftists in late August, <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

had realized <strong>the</strong> seriousness of <strong>the</strong> situati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> had begun devising tactical<br />

answers to satisfy <strong>the</strong> judges. Compared to <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin, <strong>the</strong>n, a greater<br />

proporti<strong>on</strong> of left-wing pris<strong>on</strong>ers survived. While each pris<strong>on</strong>er affiliated<br />

with <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin was tried as a Mohareb (“he who declares war <strong>on</strong> God”),<br />

authorities instead c<strong>on</strong>sidered a leftist a Mortad (“apostate”). 64 Determining<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r a pris<strong>on</strong>er was a Mortad—a charge itself subdivided into mortad-e<br />

fetri (“innate apostate”) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> mortad-e melli (“nati<strong>on</strong>al apostate”), <strong>the</strong> former<br />

category punishable by death—required unique questi<strong>on</strong>ing. 65 As<br />

Abrahamian describes it, <strong>the</strong> hearings were “an inquisiti<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> full sense<br />

of <strong>the</strong> term—an investigati<strong>on</strong> into religious beliefs ra<strong>the</strong>r than into political<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> organizati<strong>on</strong>al affiliati<strong>on</strong>s. C<strong>on</strong>spicuously absent from <strong>the</strong>m were<br />

62. AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra note 19, at 16 (emphasis omitted).<br />

63. GHAFFARI, supra note 23, at 245.<br />

64. ABRAHAMIAN, supra note 6, at 210.<br />

65. Id. at 213.

238 Harvard Human Rights Journal / Vol. 20<br />

<strong>the</strong> issues that had c<strong>on</strong>cerned <strong>the</strong> preceding tribunals—issues such as ‘subversi<strong>on</strong>,’<br />

‘treas<strong>on</strong>,’ ‘espi<strong>on</strong>age,’ ‘terrorism,’ <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‘imperialist links.’” 66<br />

Judges first questi<strong>on</strong>ed pris<strong>on</strong>ers about <strong>the</strong>ir political affiliati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong>n<br />

asked: “Are you a Muslim?”; “Do you pray?”; “Do you believe in heaven<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> hell?”; <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> “Do you read <strong>the</strong> Koran?” 67 After a few minutes of questi<strong>on</strong>ing,<br />

guards forced those pris<strong>on</strong>ers who had given “incorrect” answers or<br />

publicly declared <strong>the</strong>mselves a<strong>the</strong>ists into a line <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> left side of <strong>the</strong> hallway<br />

leading to <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong> hall, just as <strong>the</strong>y had with <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin a few<br />

weeks earlier.<br />

In Evin, <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers wore blindfolds during <strong>the</strong>ir trial. In Gohar-Dasht,<br />

however, <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong>ers could see <strong>the</strong>ir inquisitors. 68 The Gohar-Dasht survivors<br />

brought before <strong>the</strong> Death Commissi<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sistently identify <strong>the</strong> same<br />

figures as sitting members of <strong>the</strong> tribunal: Tehran prosecutor Morteza<br />

Eshraghi, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g> Court Judge Jaafar Nayyeri, Deputy Tehran Prosecutor<br />

Ebrahim Raisee, Deputy Minister of Intelligence Mustafa Pour-<br />

Mohammadi, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> aforementi<strong>on</strong>ed warden Davood Lashgari. 69 O<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

have menti<strong>on</strong>ed Ismail Shoushtari, <strong>the</strong> head of <strong>the</strong> state pris<strong>on</strong> organizati<strong>on</strong><br />

in 1988 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> later <strong>the</strong> Justice Minister, in c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong> Death Commissi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

70 The Death Commissi<strong>on</strong> in Evin pris<strong>on</strong> was likely comprised of<br />

<strong>the</strong> same officials, though Seyyed Hossein Mortazavi, warden of Evin, probably<br />

replaced Lashgari.<br />

Not <strong>on</strong>ly were <strong>the</strong> killings cruel <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> unwarranted, but <strong>the</strong>y were also<br />

arbitrary. A pris<strong>on</strong>er’s chance of survival depended first <strong>on</strong> his or her pris<strong>on</strong><br />

assignment. In Evin, where “<strong>the</strong>re was no way for pris<strong>on</strong>ers to communicate<br />

with each o<strong>the</strong>r,” pris<strong>on</strong>ers faced a greater chance of executi<strong>on</strong> because <strong>the</strong>y<br />

had no opportunity “to prepare answers to questi<strong>on</strong>s put to <strong>the</strong>m by <strong>the</strong><br />

‘Death Commissi<strong>on</strong>’ as pris<strong>on</strong>ers in [Gohar-Dasht] had d<strong>on</strong>e.” 71 The survivors<br />

also describe <strong>the</strong> trials <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> executi<strong>on</strong>s as scenes of chaos. Mistakes regularly<br />

occurred; pris<strong>on</strong> guards—sometimes in error <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> sometimes<br />

deliberately—sent pris<strong>on</strong>ers found to be “innocent” to <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong> line. 72<br />

According to Amnesty Internati<strong>on</strong>al, “[s]ome pris<strong>on</strong>ers who had been sentenced<br />

to death by <strong>the</strong> commissi<strong>on</strong> were spared because pris<strong>on</strong> guards sent<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>ers whom <strong>the</strong>y disliked to be executed in <strong>the</strong>ir place.” 73 Tragically,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are currently no verifiable descripti<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong> hall—no pris<strong>on</strong>er<br />

who entered it lived to tell about it.<br />

The <strong>on</strong>ly political pris<strong>on</strong>ers to collectively escape <strong>the</strong> mass executi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

were women affiliated with secular left parties, though even <strong>the</strong>y suffered<br />

66. Id. at 212.<br />

67. Id.<br />

68. Id. at 211.<br />

69. Id. at 210; GHAFFARI, supra note 23, at 248.<br />

70. CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY, supra note 32, at 57.<br />

71. AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra note 19, at 17.<br />

72. Days of <strong>the</strong> Executi<strong>on</strong> Lottery, supra note 42, at 65.<br />

73. AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra note 19, at 17.

2007 / <str<strong>on</strong>g>With</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rage</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rancor</str<strong>on</strong>g> 239<br />

some casualties. “Whereas Mojahedin women were promptly hanged as<br />

‘armed enemies of God,’” leftist women were not deemed sufficiently aut<strong>on</strong>omous<br />

agents to be killed as apostates. 74 Professor Reza Afshari accurately<br />

observes that “[t]his <strong>on</strong>e misogynist rule saved some lives!” 75 But <strong>the</strong><br />

government’s misogyny did not save all women. The U.N. Special Representative<br />

to Iran has reported <strong>on</strong> allegati<strong>on</strong>s from families of female<br />

Mojahedin pris<strong>on</strong>ers who claim to have “received from administrative officials<br />

a certificate of marriage of <strong>the</strong>ir impris<strong>on</strong>ed daughters. These certificates<br />

c<strong>on</strong>cerned female pris<strong>on</strong>ers who had allegedly been raped before<br />

executi<strong>on</strong>.” 76<br />

While <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin women faced death <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> possibly rape, leftist female<br />

pris<strong>on</strong>ers received brutal floggings if <strong>the</strong>y refused to pray. 77 Suicides were<br />

comm<strong>on</strong> am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> female pris<strong>on</strong>ers who could no l<strong>on</strong>ger cope with <strong>the</strong><br />

psychological trauma of pris<strong>on</strong> life. 78 Baradaran, a leftist pris<strong>on</strong>er, notes<br />

that <strong>the</strong> physical torment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> psychological pressure of this period<br />

prompted some of her friends to kill <strong>the</strong>mselves by drinking toxic cleaning<br />

fluids. 79<br />

This brutality, which lasted for nearly three m<strong>on</strong>ths, was carried out in<br />

complete secrecy. Officials did not provide any informati<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> families<br />

of pris<strong>on</strong>ers until after <strong>the</strong> “emergency” had ended. Prior to receiving news<br />

of <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong>s, family members tried to ascertain <strong>the</strong> fate of <strong>the</strong>ir impris<strong>on</strong>ed<br />

relatives by bringing clo<strong>the</strong>s, medicine, or m<strong>on</strong>ey to <strong>the</strong> pris<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong><br />

hope that <strong>the</strong>y could obtain a signed receipt from <strong>the</strong>ir loved <strong>on</strong>es, indicating<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y were still alive. 80 When rumors began to circulate about possible<br />

executi<strong>on</strong>s, “distraught family members searched <strong>the</strong> cemeteries for<br />

signs of <strong>the</strong> newly dug graves which might c<strong>on</strong>tain <strong>the</strong>ir relatives’ bodies.”<br />

81 An Amnesty Internati<strong>on</strong>al newsletter reported <strong>on</strong> “a woman who<br />

dug up <strong>the</strong> corpse of an executed man with her bare h<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s as she searched<br />

for her husb<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>’s body in Jadeh Khavaran cemetery in Tehran in August.” 82<br />

She is quoted as saying:<br />

Groups of bodies, some clo<strong>the</strong>d, some in shrouds, had been buried<br />

in unmarked shallow graves in <strong>the</strong> secti<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> cemetery<br />

reserved for executed leftist political pris<strong>on</strong>ers . . . . [T]he stench<br />

74. ABRAHAMIAN, supra note 6, at 214; Mohajer, supra note 24, at 6.<br />

75. AFSHAHRI, supra note 16, at 112.<br />

76. U.N. Ec<strong>on</strong>. & Soc. Council [ECOSOC], Comm. <strong>on</strong> Hum. Rts. <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Situati<strong>on</strong> of Hum. Rts. in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Islamic Republic of Iran, Situati<strong>on</strong> of Human Rights in <strong>the</strong> Islamic Republic of Iran, 27, U.N. Doc. A/<br />

44/620 (Nov. 2, 1989) (prepared by Reynaldo Galindo Pohl) [hereinafter Situati<strong>on</strong> of Human Rights in<br />

Iran].<br />

77. BARADARAN, supra note 41, at 391.<br />

78. Id. at 398.<br />

79. Id.<br />

80. THE MASSACRE OF POLITICAL PRISONERS, supra note 19, at 192; AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra<br />

note 19, at 13; Mohajer, supra note 24, at 7.<br />

81. AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra note 19, at 13.<br />

82. Mass Executi<strong>on</strong>s of Political Pris<strong>on</strong>ers, AMNESTY INT’L NEWSL., Feb. 1989.

240 Harvard Human Rights Journal / Vol. 20<br />

of <strong>the</strong> corpses was appalling but I started digging with my h<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

because it was important for me <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> my two little children that I<br />

locate my husb<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>’s grave. 83<br />

In Tehran, Iranian authorities usually transported <strong>the</strong> bodies to a special<br />

graveyard known comm<strong>on</strong>ly as Lanat-Abad (“The Place of <strong>the</strong> Damned”).<br />

A report prepared by <strong>the</strong> Mojahedin organizati<strong>on</strong> lists twenty-<strong>on</strong>e mass<br />

graves across <strong>the</strong> country c<strong>on</strong>taining bodies of those executed in 1988. 84<br />

Iranian authorities eventually c<strong>on</strong>tacted <strong>the</strong> families of pris<strong>on</strong>ers by letter<br />

or teleph<strong>on</strong>e. Many families simply received instructi<strong>on</strong>s to visit <strong>the</strong> Islamic<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g> Committee office to receive news of <strong>the</strong>ir pris<strong>on</strong>er. Once<br />

<strong>the</strong>re, “<strong>the</strong>y were informed of <strong>the</strong> executi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> required to sign undertakings<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y would not hold a funeral or any o<strong>the</strong>r mourning cerem<strong>on</strong>y.”<br />

85 Authorities typically did not tell relatives ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> burial place<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir loved <strong>on</strong>e or how <strong>the</strong>ir relative was executed. Even if a family knew<br />

where <strong>the</strong> body of <strong>the</strong>ir relative was buried, <strong>the</strong>y “were told that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

should not hold any funeral cerem<strong>on</strong>y.” 86 Despite <strong>the</strong> orders, families sometimes<br />

defied <strong>the</strong> authorities <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> erected small m<strong>on</strong>uments to <strong>the</strong>ir executed<br />

relatives. According to reports received by Amnesty Internati<strong>on</strong>al, such<br />

m<strong>on</strong>uments erected in Beheshte Zahra, Tehran’s main cemetery, often made<br />

up of little more than a few st<strong>on</strong>es <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> some flowers, “were removed by <strong>the</strong><br />

authorities prior to <strong>the</strong> visit to Tehran by <strong>the</strong> UN Special Representative <strong>on</strong><br />

Iran in January 1990. This was apparently an attempt to remove visible<br />

evidence of <strong>the</strong> mass killings from <strong>the</strong> site of a possible inspecti<strong>on</strong> by <strong>the</strong><br />

Special Representative.” 87 In additi<strong>on</strong>, when a U.N. human rights investigator<br />

visited Iran in 1990, <strong>the</strong> government prevented <strong>the</strong> families of <strong>the</strong><br />

1988 victims from reaching his office. 88<br />

Almost immediately after <strong>the</strong> massacre, <strong>the</strong> government launched a wellorganized<br />

internati<strong>on</strong>al misinformati<strong>on</strong> campaign, downplaying <strong>the</strong> extent<br />

of <strong>the</strong> killing <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> attempting to link all political pris<strong>on</strong>ers to <strong>the</strong><br />

Mojahedin’s military incursi<strong>on</strong>. According to Amnesty Internati<strong>on</strong>al, Ali<br />

Akbar Rafsanjani (<strong>the</strong>n-Parliament Speaker) denied <strong>the</strong> widespread executi<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

telling French televisi<strong>on</strong> that “<strong>the</strong> number of political pris<strong>on</strong>ers executed<br />

in <strong>the</strong> past few m<strong>on</strong>ths was less than 1,000.” 89 Then-President<br />

Khamenei also acknowledged that some people had been killed, but<br />

claimed that <strong>the</strong> state <strong>on</strong>ly executed “those who have links from inside<br />

pris<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong> hypocrites [M<strong>on</strong>afeqin] who mounted an armed attack inside<br />

<strong>the</strong> territory of <strong>the</strong> Islamic Republic.” 90 Iran’s Ambassador to <strong>the</strong><br />

83. Id.<br />

84. CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY, supra note 32, at 81.<br />

85. AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra note 19, at 14.<br />

86. Id.<br />

87. Id. at 15.<br />

88. Oppositi<strong>on</strong> Rallies in Public, IRAN TIMES, Feb. 2, 1990, at 1.<br />

89. AMNESTY INT’L REPORT, supra note 19, at 12.<br />

90. Id.

2007 / <str<strong>on</strong>g>With</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Revoluti<strong>on</strong>ary</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rage</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Rancor</str<strong>on</strong>g> 241<br />

U.N., Ja’afar Mahallati, criticized Amnesty Internati<strong>on</strong>al for siding with<br />

“terrorist groups opposed to <strong>the</strong> Iranian government.” 91 He claimed that<br />

<strong>the</strong> victims had “direct organisati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>tacts with <strong>the</strong> army which invaded<br />

<strong>the</strong> sovereignty <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> territorial integrity of Iran, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> which, through a<br />

treacherous espi<strong>on</strong>age network, realised <strong>the</strong> enemy’s aggressive intenti<strong>on</strong>s.”<br />

92 In a statement verging <strong>on</strong> outright denial, Iran’s <strong>the</strong>n-Interior<br />

Minister told <strong>the</strong> U.N. Special Representative that “a campaign had been<br />