Michael Wesch

Michael Wesch

Michael Wesch

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

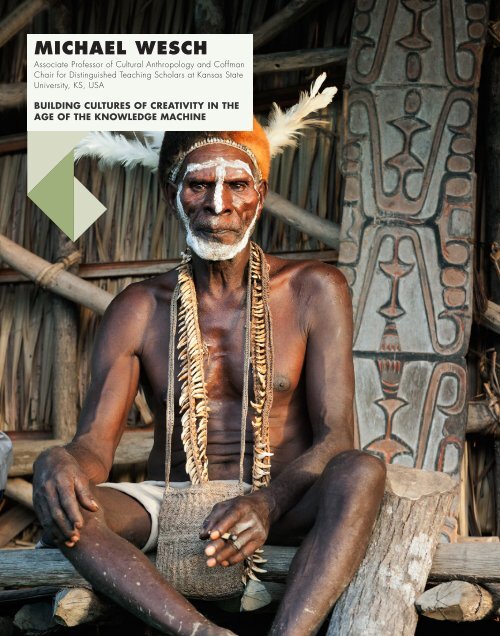

MICHAEL WESCH<br />

Associate Professor of Cultural Anthropology and Coffman<br />

Chair for Distinguished Teaching Scholars at Kansas State<br />

University, KS, USA<br />

BUILDING CULTURES OF CREATIVITY IN THE<br />

AGE OF THE KNOWLEDGE MACHINE

Building cultures of creativity in the age<br />

of the Knowledge Machine<br />

<strong>Michael</strong> <strong>Wesch</strong><br />

Twenty years ago, Seymour Papert visited a preschool where he<br />

was drawn into a discussion led by inquisitive four-year-olds on<br />

the matter of how giraffes sleep. He was impressed by what he<br />

called “a bumper crop of good theories” but no theory could<br />

come to grips with the matter of where the giraffe would put<br />

its head (Papert, 1993). Though Papert himself had grown up<br />

in Africa, he had to admit that he did not know how a giraffe<br />

slept, and so it remained a mystery.<br />

sleep” of giraffa camelopardalis which explain that a giraffe<br />

often sleeps by resting its head on its “croup” - and if you<br />

don’t know what a croup is you can perform an image search<br />

which will reveal a picture of the position: the giraffe’s long<br />

neck twisting around to its hind-quarters including the clever<br />

caption, “Oh Butt, I love you.”<br />

That evening, Papert did what people often did twenty years<br />

ago when confronted by such a mystery. He consulted his personal<br />

library of books. He never did find out how giraffes sleep.<br />

Even his great library was not up to the task. However, Papert<br />

also knew that such barriers were about to fall. He imagined a<br />

machine that would allow even small children to use “speech,<br />

touch, or gestures” to quickly navigate “through a knowledge<br />

space much broader than the contents of any printed encyclopedia.”<br />

He called it “the Knowledge Machine” (Papert, 1993).<br />

And here we are. Billions of people are connecting and collaborating<br />

on a global network and the artifacts of this collaboration<br />

- which include enough knowledge and know-how to<br />

dwarf even the greatest libraries throughout all of history - is<br />

now accessible with any one of the various devices that we<br />

carry around with us. This “Knowledge Machine” will give you<br />

56,000 videos of giraffes ranging from jerky cell phone footage<br />

to costly Animal Planet productions, and over 15,000 websites<br />

that directly answer the question of how giraffes sleep. Google<br />

Scholar offers several scientific articles on the “paradoxical<br />

Cultures of Creativities<br />

73

However, Papert was not interested in simple information<br />

retrieval, nor would he have been especially impressed by<br />

online educational efforts like Massive Open Online Courses<br />

(MOOCs) and the Khan Academy which promise to radically<br />

change education. Such efforts may be more efficient and<br />

sometimes better forms of “instruction”, but Papert was not as<br />

interested in “instruction” as he was in helping students learn.<br />

In contrast to “instructionism” Papert proposed “constructionism”<br />

as an alternative mode of educational innovation,<br />

noting that knowledge is constructed by the learner, rather<br />

than transmitted by the teacher, and that one of the best ways<br />

to inspire and facilitate knowledge construction is to engage<br />

learners in constructing a meaningful product (Papert & Harel,<br />

1991).<br />

By harnessing and leveraging the “Knowledge Machine” to<br />

engage students in real problems and projects, Papert hoped<br />

to fulfill the vision of John Dewey 100 years before him<br />

(Papert, 1998). That way the otherwise authoritarian school<br />

environments that dictated to students what they should learn,<br />

and how they should learn it, while often doing great harm to<br />

their sense of autonomy and self-efficacy might be usurped.<br />

A strong sense of autonomy and self-efficacy is essential to creativity<br />

across all cultures, and finding creative domains within<br />

any given culture is often an exercise in finding spaces where<br />

authority is not pervasive, prescriptive, or unwelcoming of<br />

alternative perspectives. Indeed, some cultures have been<br />

misunderstood as placing less value on creativity simply because<br />

the domain where we might expect creativity (namely “art”<br />

which in the Western conception includes paintings, sculpture,<br />

and music) is heavily regulated and ritualized due to the power<br />

inherent in the created objects.<br />

For example, when I was doing my anthropological fieldwork<br />

among the Nekalimin in New Guinea I became interested in<br />

decorating my house with a traditional-style Nekaliin houseboard.<br />

Among the Nekalimin, houseboards are large planks of<br />

wood standing about 6 to 8 feet high decorated with geometric<br />

patterns of diamonds and triangles in red, black, and white. To<br />

my surprise, nobody could make one for me. They do not look<br />

especially difficult to make. There is little precision to their<br />

construction, the geometric designs are imprecise and fairly<br />

haphazard, lines are not straight, and paints are often mixed<br />

and smudged with little care. I was certain that it would be an<br />

easy thing to make, so I asked my friend Peni why nobody could<br />

make one for me. Peni explained that while the skill to make a<br />

houseboard was not especially great, the knowledge required<br />

to design one was reserved only for those who had been properly<br />

initiated. Houseboards are not just symbols of power,<br />

they are power, and painting one required that a particular set<br />

of ritual procedures and taboos be followed.<br />

Such rituals and taboos have led many people to report that<br />

cultures such as the Nekalimin lack a culture of innovation and<br />

creativity, but this is not true. On another occasion I climbed<br />

the mountain to Peni’s house to find him skillfully cutting<br />

a trough through the middle of a branch of wood about two<br />

Cultures of Creativities<br />

74

meters long. He then took two nails and hammered them in<br />

to the ends of the trough and went into his house to retrieve<br />

something. He came out with some old and beaten batteries<br />

that he had warmed in the fire and carefully lined them up in<br />

the trough between the two nails. He tied two wires to the nails<br />

and connected them to an old radio. He playfully laughed at his<br />

accomplishment as the radio came to life and started to sing.<br />

Over the next several years I would watch Peni fix many radios.<br />

He had no formal training. He simply studied the objects and<br />

through trial and error built up a repertoire of techniques.<br />

Throughout our schooling, which is largely based on “instruction<br />

ism,” we have been taught that knowledge comes from the<br />

expert. Peni’s knowledge of the radio developed because there<br />

was no expert. Unschooled, he was not limited to the solutions<br />

that might be taught by the expert, and so his axe was as likely<br />

to be used for a tool as a soldering iron. He mixed and melded<br />

the knowledge from many domains of his life to become a<br />

master radio technician unlike any in the Western world.<br />

This is not to say that he would not benefit from learning from<br />

otherswith expert knowledge of this domain. The example<br />

portraysa peculiar and very subtle double-aspect of expertise.<br />

On the one hand, we have all experienced the power of learning<br />

from a skilled master who can guide us beyond our current<br />

capacities. But if, on the other hand, this guidance becomes<br />

authoritarian prescription, such expertise will come at the cost<br />

of autonomy and self-efficacy.<br />

become reliant on procedures, and when they do not know a<br />

procedure for solving the problem at hand they tend to shut<br />

down and wait for the authority to guide them.<br />

When Papert and Sherry Turkle examined computer classes in<br />

the late 1980s and early 1990s they found several examples of<br />

otherwise bright and creative students shutting down as their<br />

teachers forced them away from their own styles of programming<br />

towards prescriptive procedures. The students became<br />

alienated from their work. One student noted that she had to<br />

become “another kind of person,” and called this her “not-me<br />

strategy” (Papert & Turkle, 1992).<br />

Cultures of creativity thrive wherever there is respect and<br />

space for multiple styles to flourish and play together, where<br />

novices can construct their own expertise by building from their<br />

own experiences and knowledge-base, and where “experts”<br />

remain open to learning.<br />

When we fully accept that knowledge is constructed by the<br />

learner and not simply passed from one person to another,<br />

we must also fully accept that the integrity, motivation, and<br />

self-efficacy of the learner are of utmost concern. The stakes<br />

are high. The “Knowledge Machine” does not run on its own.<br />

Without self-motivation, curiosity, and a strong sense of<br />

autonomy and self-efficacy the “Knowledge Machine” becomes<br />

nothing but a grand and powerful distraction device.<br />

The subtlety of this distinction can be illustrated with the<br />

following example. Children learning double-column addition<br />

(such as 57+25) will be told to add the “ones” column first<br />

(7+5=12), carry the 1 to the tens column, and then add the<br />

tens. Constance Kamii has shown that children universally<br />

prefer to add the tens first, and can very easily accomplish<br />

these calculations in their head in this manner (50 + 20 = 70<br />

+ 12 = 82) (Kamii & Joseph, 1988). Forcing children to add<br />

the ones column first teaches them a “procedure” that they<br />

can then apply to very large addition problems later on, but it<br />

does so at the expense of them losing their direct sense of the<br />

numbers. They start to approach math as a set of procedures<br />

that must be applied, so that when they later encounter a larger<br />

problem such as 57,123 + 25,019, they are unlikely or even<br />

unable to quickly assess that the solution will be about 82,000,<br />

or to realize that in fact the entire problem is relatively simple<br />

when broken down sensibly rather than procedurally (adding<br />

19 to 123 + 82,000 = 82,142). The larger effect is that they<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Kamii, C. & Joseph, L. (1988), ‘Teaching Place Value and Double-Column Addition’,<br />

Arithmetic Teacher, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 48-52.<br />

Papert, S. (1993), The Children’s Machine: Rethinking School in the Age of the<br />

Computer, New York, NY: Basic Books.<br />

Papert, S. (1998), Child Power: Keys to the New Learning of the Digital Century,<br />

Colin Cherry Memorial Lecture at the Imperial College, London. June 2, 1998,<br />

accessed: May 2013, available from: http://www.papert.org/articles/Childpower.<br />

html.<br />

Papert, S. & Harel, I. (1991), Constructionism, New York, NY: Ablex Publishing<br />

Corporation.<br />

Papert, S. & Turkle, S. (1992), ‘Epistemological Pluralism and the Revaluation of the<br />

Concrete’, Journal of Mathematical Behavior, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 3-33.<br />

Cultures of Creativities<br />

75