Wake Forest Magazine June 2003 - Past Issues - Wake Forest ...

Wake Forest Magazine June 2003 - Past Issues - Wake Forest ...

Wake Forest Magazine June 2003 - Past Issues - Wake Forest ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

C a m p u s C h r o n i c l e<br />

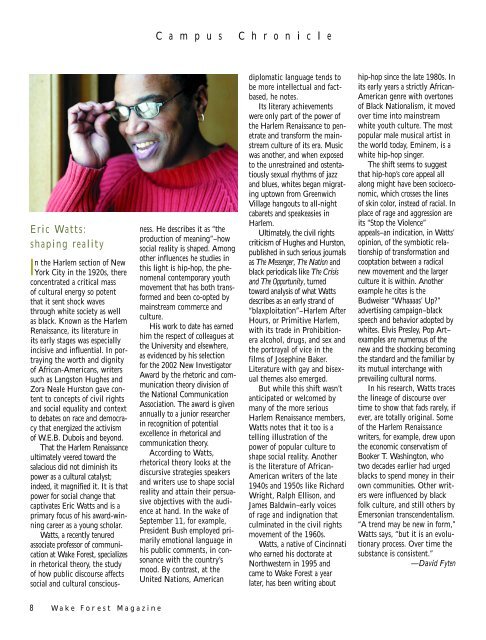

Eric Watts:<br />

shaping reality<br />

In the Harlem section of New<br />

York City in the 1920s, there<br />

concentrated a critical mass<br />

of cultural energy so potent<br />

that it sent shock waves<br />

through white society as well<br />

as black. Known as the Harlem<br />

Renaissance, its literature in<br />

its early stages was especially<br />

incisive and influential. In portraying<br />

the worth and dignity<br />

of African-Americans, writers<br />

such as Langston Hughes and<br />

Zora Neale Hurston gave content<br />

to concepts of civil rights<br />

and social equality and context<br />

to debates on race and democracy<br />

that energized the activism<br />

of W.E.B. Dubois and beyond.<br />

That the Harlem Renaissance<br />

ultimately veered toward the<br />

salacious did not diminish its<br />

power as a cultural catalyst;<br />

indeed, it magnified it. It is that<br />

power for social change that<br />

captivates Eric Watts and is a<br />

primary focus of his award-winning<br />

career as a young scholar.<br />

Watts, a recently tenured<br />

associate professor of communication<br />

at <strong>Wake</strong> <strong>Forest</strong>, specializes<br />

in rhetorical theory, the study<br />

of how public discourse affects<br />

social and cultural consciousness.<br />

He describes it as “the<br />

production of meaning”–how<br />

social reality is shaped. Among<br />

other influences he studies in<br />

this light is hip-hop, the phenomenal<br />

contemporary youth<br />

movement that has both transformed<br />

and been co-opted by<br />

mainstream commerce and<br />

culture.<br />

His work to date has earned<br />

him the respect of colleagues at<br />

the University and elsewhere,<br />

as evidenced by his selection<br />

for the 2002 New Investigator<br />

Award by the rhetoric and communication<br />

theory division of<br />

the National Communication<br />

Association. The award is given<br />

annually to a junior researcher<br />

in recognition of potential<br />

excellence in rhetorical and<br />

communication theory.<br />

According to Watts,<br />

rhetorical theory looks at the<br />

discursive strategies speakers<br />

and writers use to shape social<br />

reality and attain their persuasive<br />

objectives with the audience<br />

at hand. In the wake of<br />

September 11, for example,<br />

President Bush employed primarily<br />

emotional language in<br />

his public comments, in consonance<br />

with the country’s<br />

mood. By contrast, at the<br />

United Nations, American<br />

diplomatic language tends to<br />

be more intellectual and factbased,<br />

he notes.<br />

Its literary achievements<br />

were only part of the power of<br />

the Harlem Renaissance to penetrate<br />

and transform the mainstream<br />

culture of its era. Music<br />

was another, and when exposed<br />

to the unrestrained and ostentatiously<br />

sexual rhythms of jazz<br />

and blues, whites began migrating<br />

uptown from Greenwich<br />

Village hangouts to all-night<br />

cabarets and speakeasies in<br />

Harlem.<br />

Ultimately, the civil rights<br />

criticism of Hughes and Hurston,<br />

published in such serious journals<br />

as The Messenger, The Nation and<br />

black periodicals like The Crisis<br />

and The Opportunity, turned<br />

toward analysis of what Watts<br />

describes as an early strand of<br />

“blaxploitation”–Harlem After<br />

Hours, or Primitive Harlem,<br />

with its trade in Prohibitionera<br />

alcohol, drugs, and sex and<br />

the portrayal of vice in the<br />

films of Josephine Baker.<br />

Literature with gay and bisexual<br />

themes also emerged.<br />

But while this shift wasn’t<br />

anticipated or welcomed by<br />

many of the more serious<br />

Harlem Renaissance members,<br />

Watts notes that it too is a<br />

telling illustration of the<br />

power of popular culture to<br />

shape social reality. Another<br />

is the literature of African-<br />

American writers of the late<br />

1940s and 1950s like Richard<br />

Wright, Ralph Ellison, and<br />

James Baldwin–early voices<br />

of rage and indignation that<br />

culminated in the civil rights<br />

movement of the 1960s.<br />

Watts, a native of Cincinnati<br />

who earned his doctorate at<br />

Northwestern in 1995 and<br />

came to <strong>Wake</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> a year<br />

later, has been writing about<br />

hip-hop since the late 1980s. In<br />

its early years a strictly African-<br />

American genre with overtones<br />

of Black Nationalism, it moved<br />

over time into mainstream<br />

white youth culture. The most<br />

popular male musical artist in<br />

the world today, Eminem, is a<br />

white hip-hop singer.<br />

The shift seems to suggest<br />

that hip-hop’s core appeal all<br />

along might have been socioeconomic,<br />

which crosses the lines<br />

of skin color, instead of racial. In<br />

place of rage and aggression are<br />

its “Stop the Violence”<br />

appeals–an indication, in Watts’<br />

opinion, of the symbiotic relationship<br />

of transformation and<br />

cooptation between a radical<br />

new movement and the larger<br />

culture it is within. Another<br />

example he cites is the<br />

Budweiser “Whaaaas’ Up?”<br />

advertising campaign–black<br />

speech and behavior adopted by<br />

whites. Elvis Presley, Pop Art–<br />

examples are numerous of the<br />

new and the shocking becoming<br />

the standard and the familiar by<br />

its mutual interchange with<br />

prevailing cultural norms.<br />

In his research, Watts traces<br />

the lineage of discourse over<br />

time to show that fads rarely, if<br />

ever, are totally original. Some<br />

of the Harlem Renaissance<br />

writers, for example, drew upon<br />

the economic conservatism of<br />

Booker T. Washington, who<br />

two decades earlier had urged<br />

blacks to spend money in their<br />

own communities. Other writers<br />

were influenced by black<br />

folk culture, and still others by<br />

Emersonian transcendentalism.<br />

“A trend may be new in form,”<br />

Watts says, “but it is an evolutionary<br />

process. Over time the<br />

substance is consistent.”<br />

—David Fyten<br />

8 W ake <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>