MORPHOLOGY

MORPHOLOGY

MORPHOLOGY

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

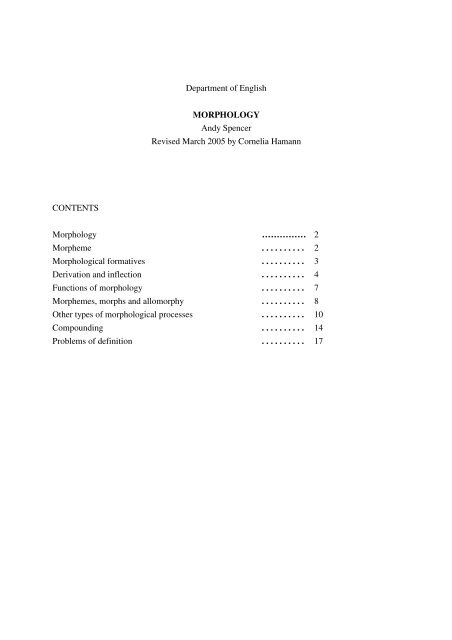

Department of English<br />

<strong>MORPHOLOGY</strong><br />

Andy Spencer<br />

Revised March 2005 by Cornelia Hamann<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Morphology …………… 2<br />

Morpheme . . . . . . . . . . 2<br />

Morphological formatives . . . . . . . . . . 3<br />

Derivation and inflection . . . . . . . . . . 4<br />

Functions of morphology . . . . . . . . . . 7<br />

Morphemes, morphs and allomorphy . . . . . . . . . . 8<br />

Other types of morphological processes . . . . . . . . . . 10<br />

Compounding . . . . . . . . . . 14<br />

Problems of definition . . . . . . . . . . 17

<strong>MORPHOLOGY</strong><br />

Morphology is about words and how they are formed. Usually, morphology is the study of form,<br />

in this case, the study of word formation.<br />

In phonology we look at sounds and larger units made up of sounds (syllables) combining<br />

into words and at the characteristic sound properties of words (e.g. vowels, syllables, stress).<br />

However, if you only know what a word sounds like, you do not really know the word. An<br />

important component is missing. Knowing a word means knowing its phonetic shape and its<br />

meaning! Meaning also includes the word category. This is what you find when you look up a<br />

word in a dictionary.<br />

(1) bachelor [ ÂazsR?k?] 1. n, unmarried man<br />

Some words are ‘basic’ in that they are one syllable words and cannot be further<br />

decomposed: hat, mat, run, back. Others may be two-syllabic and still no further decomposition<br />

is possible: bacon, sister, water. However, there are one-syllabic words where you might feel that<br />

they are not ‘basic’, that they are somehow made up of more than one component: hats, runs, ran.<br />

There are also bysyllabic (and polysyllabic) words where each syllable seems to contribute to the<br />

word: baker, runner, unread, decode, decodable, or the monster:<br />

pneumoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis.<br />

This ‘feeling’ is based on the intuition that words are made up of smaller meaningful units<br />

which keep their meaning and contribute it to the word’s meaning and that such combinations are<br />

rule governed. This intuition sometimes breaks through: “In two words: im-possible”, Sam<br />

Goldwyn, the film producer said. He was no linguist; these are, of course, not two words, there is<br />

a better term: Morpheme. Morphemes can be words (hat, run, think), but usually they are smaller<br />

units than words.<br />

MORPHEMES<br />

If you take the English noun code, you can form the verb decode from it. The word decode is<br />

clearly made up of code and de-, and the meaning is fairly transparently derived from the meaning<br />

of its two parts. Moreover, this case is not isolated. You can attach de- to all kinds of nouns to<br />

form a verb. Often the meaning will be easy to work out from the meaning of the original noun:<br />

e.g. deflea. Sometimes, the meaning will be restricted to special contexts, such as defrost (which<br />

2

tends to be used of refrigerators, frozen food, and cars). Sometimes, you simply have to learn the<br />

meaning separately (as with defrock, deflower).<br />

From the verb decode we can form the adjective decodable by adding -able. Again, -able<br />

can be added to a lot of verbs: readable, eatable, movable. Having created this word we can<br />

negate it by adding un- to get undecodable. This, too, is a very general process, and it allows us to<br />

negate a great many adjectives in English: unattractive, undisturbed, uncomfortable. Finally, we<br />

can come full circle by creating a noun from our adjective: undecodability. Almost any adjective<br />

ending in -able or -ible forms a noun of this sort by adding -ity.<br />

In each case we have created a new word by adding something to an old word. What we<br />

have added are linguistic units which have their own meaning, and which combine in given ways<br />

to form words. Any such unit, if it is minimal (that is, if it is not possible to break it into smaller<br />

such units), is called a morpheme. The standard definition of a morpheme is “the minimal<br />

meaningful unit” in the language.<br />

A morpheme can also be called a “minimal linguistic sign” – a grammatical unit in which<br />

there is an arbitrary union of sound (signifiant) and meaning (signifié) and that cannot be further<br />

analysed.<br />

A word such as undecodability consists of several morphemes and is therefore<br />

polymorphemic. The original word code, on the other hand, consists of just one morpheme. It is<br />

therefore a monomorphemic word. Equally, we could say that it is simultaneously a word and a<br />

morpheme. A morpheme such as code, which can exist separately, i.e. on its own, is also called a<br />

free morpheme, while morphemes such as un- and -ity, which have to be attached to other<br />

morphemes, are called bound morphemes.<br />

You find words composed of one morpheme (boy, desire), of two morphemes (boy+ish,<br />

desire+able), of three morphemes (boy+ish+ness, desire+able+ity), of four morphemes<br />

(gentle+man+ly+ness, un+desire+able+ity) and of more than four morphemes<br />

(un+gentle+man+ly+ness, anti+dis+establish+ment+ari+an+ism).<br />

MORPHOLOGICAL FORMATIVES<br />

The commonest sorts of bound morphemes are those which have to be attached to the beginning<br />

of a word (prefixes) or to the end (suffixes). A general term covering both types is affix, and the<br />

process of adding a prefix or a suffix (that is, the processes of prefixation and suffixation) is<br />

called affixation. Sometimes, it is important to have a separate term for the thing to which we<br />

add the affixes. Several such terms are commonly used: root, and stem are ones which are often<br />

seen. We will use the term stem to mean any string of morphemes to which an affix is attached. If<br />

3

the stem is itself monomorphemic (e.g. code) we will call it a root. In our example, therefore, we<br />

added de- to the stem code, which was also a root. Then we added -able to the stem decode,<br />

though this stem would not be called a root. Later, we will look at other ways of forming or<br />

changing words.<br />

DERIVATION AND INFLECTION<br />

So far, we have seen how to create new words using affixes such as de-, un-, -able and -ity. The<br />

process of creating novel words is called derivational morphology (or derivation), and we<br />

could refer to these formatives as derivational affixes. However, once we have a word we often<br />

find that it appears in different forms, depending on its grammatical function or its position in the<br />

sentence. Consider the different forms of the verb bake in the sentences in (2):<br />

(2) a. Bake me a cake!<br />

b. He bakes very good cakes.<br />

c. They bake very good cakes.<br />

d. They are baking a cake.<br />

e. She has baked us a cake.<br />

f. This cake was baked for us.<br />

g. They like to bake cakes.<br />

h. He enjoys baking cakes.<br />

The verb bake appears in four different forms, corresponding to a number of grammatical<br />

functions. These are shown in (3):<br />

(3) a. bake imperative; infinitive; present (except 3rd sg.)<br />

b. bakes 3rd sg. present<br />

c. baking present participle; gerund<br />

d. baked past tense; past participle; passive participle<br />

Three of these forms involve affixation (specifically suffixation). Except for the verb be, it is<br />

always the case in English that the imperative, infinitive and non-3rd sg. present tense are the<br />

same; that the present participle and the gerund are the same; and that the past participle (used<br />

with the auxiliary verb have) and the passive participle are the same. However, in some verbs the<br />

past tense and the past/passive participle are different. These are the so-called strong verbs:<br />

4

(4) a. They write songs.<br />

b. He writes songs.<br />

c. She is writing a song.<br />

d. He wrote a song.<br />

e. They have written a song.<br />

f. The song was written for us.<br />

In the verb write the past tense is wrote but the past participle is written. In all these cases we are<br />

speaking of different forms of a single verb, not of the creation of a new verb. This kind of<br />

morphology is called inflectional morphology or inflection.<br />

In English, three major categories inflect. In addition to verbs, which were discussed<br />

above, these are nouns and adjectives. Nouns appear in a singular form and a plural form. Some<br />

examples will be given later. Adjectives (and adverbs) appear in a comparative form (-er) and a<br />

superlative form (-est): short, shorter, shortest.<br />

The function of derivational morphology is the creation of new words from old ones. This<br />

means that it will usually (but not necessarily always) be the case that the word created by a<br />

derivational process will belong to a different syntactic category from the word which forms its<br />

stem. For instance, -ity turns adjectives into nouns, -able turns verbs into adjectives, and so on.<br />

Some more derivational affixes of English are listed below (see also Fromkin, Rodman and<br />

Hyams (2003)):<br />

DERIVATE BASE Adjective Verb Noun<br />

Noun boy-ish motor-ize boy-hood<br />

Rom-an vaccin-ate lion-ess<br />

lady-like en-circle Marx-ist<br />

Verb generat-ive un-do sing-er<br />

resent-ful mis-hear employ-ee<br />

absorb-ent re-do defam-ation<br />

Adjective green-ish black-en white-ness<br />

counter-intuitive pur-ify free-dom<br />

un-happy<br />

social-ist<br />

Notice that some of these affixes appear in more than one category.<br />

5

Inflection creates a new form of a given word, not a new word. By defintion, therefore, an<br />

inflectional morpheme shouldn’t change the syntactic category of the word it attaches to. There’s<br />

a slight problem here with the participles. We’d like to say that a participle such as amusing or<br />

amused is an inflectional form, particularly since it is clearly a verb form in sentences such as (5).<br />

Yet they frequently appear as adjectives as in (6):<br />

(5) a. Tom is amusing the children (with his stories).<br />

b. The children are being amused (by Tom’s stories).<br />

(6) a. Dick’s story was not particularly amusing.<br />

b. Harriet was not very amused by Dick’s stories.<br />

c. Harriet remained unamused by Dick’s stories.<br />

We’ll discuss a possible explanation for this discrepancy in a later section.<br />

(English) Morphemes<br />

Bound<br />

Free<br />

Affix Root Open Closed<br />

-ceive class class<br />

-mit girl (N) and (Conj)<br />

-fer pretty (A) in (P)<br />

love (V) the (Det)<br />

now (Adv) she (pronoun)<br />

is (Aux)<br />

derivational<br />

inflectional<br />

prefix suffix<br />

suffix<br />

pre- -ly -s, -ing, -ed, -en<br />

un- -ist -s, -’s<br />

con- -ment -er, -est<br />

6

FUNCTIONS OF <strong>MORPHOLOGY</strong><br />

The -s form of the verb has the function of signalling agreement between the verb and a subject<br />

in the third person singular (in the present tense). Agreement in English is limited essentially to<br />

this case, though in other languages it may be much more extensive.<br />

A minor form of inflection is seen with English pronouns. Compare the examples of (7) to<br />

(9):<br />

(7) a. He loves her.<br />

b. She loves him.<br />

(8) a. I knew them.<br />

b. They knew me.<br />

(9) a. They took the book from her and gave it to him.<br />

b. He took the book from them and gave it to me.<br />

In these examples we see that the pronouns adopt a special form when they come after a verb or a<br />

preposition. We can say that the verb or the preposition governs the pronoun and that a pronoun<br />

which is so governed has to appear in a special form (a type of inflection). In other languages all<br />

nouns have to appear in a specially inflected form after a verb or a preposition (think of examples<br />

in a language you know such as German or Latin).<br />

In other cases the inflected form is used simply to express a meaning which is<br />

grammaticalized. Different languages choose to grammaticalize different meanings. In English<br />

(and French), for instance, the meaning ‘to cause someone to do something’ is expressed in a<br />

separate verb such as make (or faire), as in example (10). In Japanese, however, this meaning is<br />

grammaticalized and a special verb ending, -ase, is used (cf. 11):<br />

(10) a. Taro made Jiro run.<br />

b. Taro a fait courir Jiro.<br />

(11) Taroo-wa Jiroo-o hashir-ase-ta<br />

Taro-subj. Jiro-obj. run-cause-past<br />

(literally: Taro run-caused Jiro)<br />

English (like French and Japanese) grammaticalizes the notion of past tense. Like French but<br />

unlike Japanese, it grammaticalizes the notion of perfect (I have/had done; J’ai/avais eu fait).<br />

Like French but unlike Japanese it grammaticalizes the notion of number (i.e. singular vs. plural).<br />

French, unlike English or Japanese, grammaticalizes the notion of imperfect tense (l’imparfait).<br />

7

MORPHEMES, MORPHS AND ALLOMORPHY<br />

We can think of morphemes in two different ways. We can view them as linguistic units which<br />

have a meaning or grammatical function (that is, we can look at their content), or we can view<br />

them as entities which have a phonological structure (that is, we can look at their form). In the<br />

first case we will be mainly interested in the way that morphemes relate to syntax; in the second<br />

case we will be interested in the way morphemes relate to each other, and the way they relate to<br />

phonology.<br />

Look carefully at the plural endings of the words in (12) (These words are given in very<br />

broad, i.e. approximative phonetic transcription):<br />

(12) a. cats /jzsr/<br />

b. dogs /cPfy/<br />

c. horses /gN9rHy/<br />

d. cows /j`Ty/<br />

The regular plural ending conventionally spelt s or es has precisely three distinct pronunciations:<br />

[r], [y] or [Hy]. These three elements are the realizations of a single morpheme, the regular plural<br />

morpheme, which we can represent abstractly as -ES. We say that /r, y, Hy/ are allomorphs of the<br />

morpheme -ES. In more general terms, we say that the form of a morpheme as it is actually<br />

pronounced in given sets of words is a morph, and where two (or more) morphs are variants of<br />

one morpheme we say they are allomorphs of that morpheme. This terminology parallels that<br />

used in phonology:<br />

morph: the particular form of linguistic unit you get when you analyse a word into its smallest<br />

meaningful components.<br />

morpheme: the more abstract, general entity represented by a morph or by sets of morphs.<br />

allomorph: one of several forms (morphs) assumed by a morpheme.<br />

(cf.: phone: a particular speech sound obtained when a word is analysed into its phonological<br />

segments.<br />

phoneme: the more abstract, general entity represented by a phone or a set of phones.<br />

allophone: one of several forms (phones) assumed by a phoneme.)<br />

8

When a morpheme has several variants (allomorphs) we speak of allomorphy. The<br />

allomorphy of the regular plural inflection, -ES, exhibited in (12), is entirely the result of regular<br />

phonological processes. We say that this is a case of phonlogically conditioned allomorphy.<br />

Sometimes, however, morphemes appear in different shapes for no particular reason.<br />

Consider the words of (13):<br />

(13) a. house /g`Tr/ houses /g`TyHy/<br />

b. knife /m`He/ knives /m`Huy/<br />

c. wreath /qh9S/ wreathes /qh9Cy/<br />

In these words it is the root (house, knife, wreath) which exhibits the allomorphy. However, this<br />

only happens to a few morphemes. Most, like spouse, fife, or death don’t show it. This type of<br />

allomorphy is said to be lexically conditioned.<br />

Occasionally, we find allomorphy which arises not because of phonology or as an<br />

idiosyncratic, lexical property of a morpheme, but because that allomorphy has been conditioned<br />

by another morpheme: we have morphologically conditioned allomorphy. A clear example of<br />

this is provided by German. German forms plurals of nouns in several relatively common and<br />

productive ways. Moreover, it has a number of suffixes which form nouns, such as -heit/-keit,<br />

-niss, -ung, -tum and so on. Any count noun formed from the suffix -heit/keit will form its plural<br />

in -en, as in (14), though in general a stem ending in, say, a vowel + /t/ might form its plural in<br />

any of a number of ways (15):<br />

(14) a. Schwachheit - en weaknesses<br />

b. Flüssigkeit - en fluids<br />

(15) a. Streit - Streite quarrels<br />

b. Kraut - Kräuter herbs<br />

c. Zeit - Zeiten times<br />

d. Braut - Bräute brides<br />

An example from English involves the two different verbs ring. Ring (1) is the verb used<br />

for the sound of bells or in the meaning of telephone, call. This is an irregular verb: ring, rang,<br />

rung. There is another verb which forms its past form with the regular suffix –ED. This is a<br />

denominal verb and has to do with rings. The rule is that if a verb form is derived from a noun,<br />

then it takes the regular past. This process is clearly morphologically conditioned.<br />

9

When allomorphy isn’t conditioned by regular phonological rules but is instead the result<br />

of lexical idiosyncrasy, we still often find that the allomorphs are fairly similar to each other<br />

phonologically. This is the case with the knife/knive allomorphy given earlier. Sometimes,<br />

however, the allomorphy might be more drastic and the variants might be quite dissimilar from<br />

each other. Some examples from derivational morphology are given in English in (16):<br />

(16) a. deceipt - deception /cHrh9s/-/ cHrdo/<br />

b. satisfy - satisfaction /e`H/-/ ezj/<br />

c. flute - flautist /ekt9s/-/ ekN9sHrs.<br />

d. France - French /eq@9m/-/eqdm/<br />

e. Shaw - Shavian /RN9/-/RdHu/<br />

When the phonological distance between two allomorphs becomes sufficiently large we speak of<br />

partial suppletion. In some cases the allomorphic variants might have absolutely nothing in<br />

common phonologically. Examples often cited are the English past tense of go which is went, and<br />

the comparative and superlative of good - better, best. This is called total suppletion (or<br />

sometimes just suppletion).<br />

OTHER TYPES OF MORPHOLOGICAL PROCESSES<br />

The languages of the world exhibit a wide variety of morphological processes, and many<br />

languages use word structure to realize grammatical functions expressed by syntactic structures in<br />

the more familiar Indo-European languages. Here is a very small sample of such processes, with<br />

exemplification from English where appropriate.<br />

One form of affixation is rather different from the standard prefixation and suffixation<br />

operations. This is the phenomenon of reduplication, in which some part of a base is repeated,<br />

either to the left or to the right, or occasionally in the middle. Tagalog, the main language of the<br />

Philippines, is a rich source of this type of morphology. In (17a) and (17b) we see that the first<br />

syllable of a root is reduplicated, while in (17c), the final syllable of the prefix has been<br />

reduplicated.<br />

(17) a. Root: sulat ‘writing’<br />

Future:<br />

susulat<br />

10

. Root: basa ‘reading’<br />

Prefixed infinitive: mambasa<br />

Nominalization:<br />

mambabasa<br />

c. Root: sulat<br />

Prefixed causative infinitive: magpasulat ‘to make write’<br />

Future:<br />

magpapasulat<br />

In (17d), we see an example of a whole root being reduplicated:<br />

(17) d. magsulatsulat ‘to write intermittently’<br />

In English, reduplication is characteristic of ‘baby talk’: e.g. mama, choo-choo, wee-wee.<br />

However, there are a number of words in the adult vocabulary which seem to involve<br />

reduplication, such as hocus-pocus, or higgledy-piggledy.<br />

Many languages allow affixes to appear inside another morpheme. The Philippine<br />

languages show this characteristically. Tagalog, for instance, uses the infixes -um- and -in- to<br />

form certain of its voice constructions with verbs. Notice that these infixes are placed inside<br />

monomorphemic roots – there is no way to decompose sulat into smaller morphemes. (The term<br />

‘active’ and ‘passive’ are not really accurate for this language, but their real nature isn’t of<br />

interest for us here.)<br />

(18) from monomorphemic root sulat (‘writing’)<br />

a. sumulat ‘to write’ (active voice)<br />

b. sinulat (passive voice)<br />

For good measure, here are some examples in which reduplication interacts with infixation:<br />

(19) a. sumulat ‘to write’ (infinitive)<br />

b. sumusulat (present tense)<br />

(20) a. bumasa ‘to read’ (infinitive)<br />

b. bumasabasa ‘to read intermittently’<br />

In (19b) we have first reduplicated the first syllable of the root (as in the future tense form (17a))<br />

and then infixed -um- to the result. In (20b), we have reduplicated the whole root, as in (17d), and<br />

again infixed -um-.<br />

11

Infixation in English is even more marginal than reduplication. However, it occurs in one<br />

construction and this is of no little theoretical interest. There is a small number of particles which<br />

can be used as infixes (the process is usually called expletive infixation). Examples are given in<br />

(21). Notice that these really are infixes because they appear inside another morpheme.<br />

(21) a. abso-bloomin’-lutely<br />

b. fan-bloody-tastic<br />

c. (Christ) Al-fucking-mighty<br />

The reason these are interesting is that there are phonological and morphological constraints on<br />

the formation of words using these infixes. It is impossible, for instance, to say *ab-bloomin’-<br />

solutely or *Christ Almigh-fucking-ty. Since the infixed particles in the main belong to<br />

vocabulary which is highly taboo it turns out that some speakers of English do not encounter such<br />

forms until their late adolescence. It has been shown that such speakers, who for sociolinguistic<br />

reasons have never been exposed to data which will allow them to formulate a rule of Expletive<br />

Infixation, nonetheless have the same judgements of well-formedness as other speakers even after<br />

hearing only one example of the construction. This is all the more remarkable since some of these<br />

speakers would never consent to using the construction themselves. This phenomenon sheds<br />

considerable light on the way linguistic representations are stored and learnt.<br />

There is another type of affix which is called a circumfix. Chickasaw, a Muscogean<br />

(American Indian) language spoken in Oklahoma has a negative morpheme consisting of ik+o.<br />

The first syllable attaches to the left of the stem, the second attaches to the right.<br />

(22) a. chokma he is good a’. ik+chokm+o he isn’t good<br />

b. lakna it is yellow b’. ik+lak+o it isn’t yellow<br />

c. palli it is hot c’. ik+pall+o it isn’t hot<br />

d. tiwwi he opens (it) d’. ik+tiww+o he doesn’t open it<br />

As both of these syllables combine to constitute one meaning, negation, ik+o is a morpheme.<br />

Such morphemes are also called discontinuous morphemes.<br />

Not all morphology involves affixation in any obvious sense. In the examples below, we<br />

see a phonological alternation functioning as a kind of morpheme. This type of morphemeinternal<br />

vowel is called apophonony or ablaut. In (23) it realizes the category of plural, and in<br />

(24) the category of past tense or past participle.<br />

12

(23) a. man men<br />

b. tooth teeth<br />

c. foot feet<br />

(24) a. write wrote<br />

b. take took<br />

c. break broke (broken)<br />

d. sing sang sung<br />

This is only found as a marginal and unproductive process in English, but in some languages<br />

similar processes are fully productive.<br />

Another marginal process involves word stress. Consider the following pairs of words (the<br />

accent marks the stressed syllable):<br />

(25) Noun Verb<br />

a. 'torment tor'ment<br />

b. 'contrast con'trast<br />

c. 'increase in'crease<br />

d. 'transport trans'port<br />

A word formation process which is extremely common in English and a number of other<br />

languages (but not very frequent in other European languages) is the process of morphological<br />

conversion. This occurs when a word in one syntactic class is simply used as a word in another<br />

class without any other morphological process applying to it. In English pretty well any<br />

monomorphemic noun (and many polymorphemic ones) can be used as a verb given the right<br />

context. Many of these have become lexicalized with special meanings:<br />

(26) a. to table a paper<br />

b. to chair a meeting<br />

c. to shelve a plan<br />

d. to pocket the proceeds<br />

Likewise, many verbs can be used as nouns:<br />

(27) a. to go - it’s your go<br />

b. to walk - to go for a walk<br />

c. to faint - to fall in a faint<br />

13

Conversion may help explain why inflection seems to involve a change of syntactic category in<br />

the case of participles used as adjectives. Perhaps what is happening is that the verb form, the<br />

participle, is simply converted to an adjective without any further morphology being necessary.<br />

Note that words belonging to other syntactic categories can also undergo conversion, e.g. up<br />

(preposition) – to up prices (verb), or, dirty (adjective) – to dirty (verb).<br />

There are several further types of word formation which can be mentioned, and which are<br />

marginal in English and other languages. A number of words have entered the English dictionary<br />

recently by a process of blending: e.g. smoke+fog = smog, breakfast+lunch = brunch. A device<br />

found in languages with alphabetic writing systems is that of the acronym, by which letters of a<br />

phrase are taken to spell a new word. This device is very popular in the United States. The best<br />

examples ‘create’ words already in existence. Some of these may even have a meaning intended<br />

to suggest the meaning of the original word, as, for example, wasp (White Anglo-Saxon<br />

Protestant). Note that the new words created from the initial letters must be pronounceable as a<br />

word (e.g. laser, REM, radar). Words such as UN, UK, OED, in which the strings of letters are<br />

unpronounceable, are sometimes referred to as alphabetisms. Other devices include clipping, by<br />

which a word is shortened, generally in colloquial style. Words such as mike (microphone), phone<br />

(telephone) and telly (television) are formed this way. This is extremely common in Australian<br />

English, which abounds in clipped words ending in -o such as avo (afternoon).<br />

A more theoretically important process is backformation, which is of interest because it<br />

sometimes tells us something about the way speakers perceive morphological structure. This<br />

occurs when a word is treated as though it is derived from another word even if it is not. Then the<br />

ghost source is assumed to exist and enters the lexicon. For instance, originally the word pedlar<br />

was monomorphemic. However, speakers analysed the -ar ending as cognate with the -er of<br />

singer or the -or of actor. But this meant there had to be a verb peddle. Since there was no such<br />

verb one had to be invented by backformation. A modern example is derived from aggression.<br />

On analogy with progress > progression we would expect there to be a verb to aggress.<br />

Originally there was none, but recently people have started using such a verb.<br />

COMPOUNDING<br />

The next morphological process is a very important one, both theoretically, from the point of<br />

view of linguistic theory, and practically, from the point of the description of English. This is the<br />

process of compounding. Compounding is essentially the process of forming words by<br />

conjoining two or more other words (though we will extend the notion slightly). There are<br />

hundreds of examples in English which are of great antiquity and which have highly specialized<br />

14

meanings. In some cases the meaning of one or other member of the compound has changed<br />

significantly when used as a separate word. Some examples are given in (28):<br />

(28) a. housewife<br />

b. penknife<br />

c. cupboard<br />

Originally, wife meant ‘woman’ (cf. German Weib) and not ‘female spouse’. A penknife is no<br />

longer (solely) used to cut quills for writing. A cupboard isn’t really a shelf (‘board’) for cups.<br />

Many lexicalized compounds (i.e. compounds which have specialized meanings) are<br />

nonetheless transparent semantically. For instance, we have the examples in (29):<br />

(29) a. boathouse<br />

b. houseboat<br />

c. typewriter<br />

d. bookcase<br />

It is also possible for English speakers to create new compounds at will, especially by<br />

compounding nouns. Thus in the right context we can form examples such as (30). In some cases<br />

it is not entirely clear whether we are dealing with a freshly formed compound or a compound<br />

which has already entered the lexicon:<br />

(30) a. morphology handout<br />

b. phonetics test<br />

c. English Department secretary<br />

d. English language degree entrance requirements<br />

Notice that it doesn’t matter that these are written as separate words. The orthography is largely<br />

arbitrary and in many cases it is not clear how best to spell a compound (‘button hole’,<br />

‘buttonhole’, ‘button-hole’?).<br />

These examples involve sets of nouns, but we can also form compounds from other<br />

syntactic categories.<br />

(31) a. Preposition + Noun: afterthought, in-crowd<br />

b. Adjective + Noun: darkroom, bluestocking<br />

c. Verb + Particle: hold-up, through-put<br />

15

d. Adjective + Verb: double-book, free-associate<br />

e. Particle + Verb: over-eat, outplay<br />

f. Noun + Adjective: childproof, fireproof, context sensitive<br />

g. Adjective + Adjective: deaf-mute, open-ended<br />

Some of these are actually produced by backformation from other constructions, for examle freeassociate<br />

is formed from the Adjective + Noun compound free-association.<br />

Compounds sometimes involve bound morphemes rather than full words. A great many<br />

‘neo-classical’ compounds formed from Greek roots are found in scientific literature for instance.<br />

Some examples are electroscope, leucocyte, cytoplasm, hydrogen. Other non-technical examples<br />

might be genocide, matriarchy, polymath.<br />

Compounding has many of the characeristics of syntax. There are two important syntactic<br />

properties exhibited by N+N compounds: recursion and constituent structure.<br />

Recursion is a property of rules or processes by which the result of a process is allowed to<br />

undergo the process again. For instance, I can apply the process of compounding to the words<br />

English and language to obtain a compound word. Since this is still a word I can use it to form<br />

another compound as in English language degree. Likewise, I can form a compound from<br />

entrance and requirements. Then I can put both of these together to get (30d). The important<br />

thing about recursion is that there is no principled way of stopping it. Nothing in the grammar of<br />

English prevents me from forming compounds which are indefinitely long.<br />

Example (30d) means ‘entrance requirements for the English language degree’. An<br />

English language degree is a degree in English language. This means that we can split up our<br />

compounds into chunks which are nonetheless larger than individual words, and these chunks<br />

correspond to the way the meaning of the whole compound is organized. The chunks are called<br />

constituents, and when we analyse the way they are grouped we are analysing the constituent<br />

structure of the compound. This can be represented graphically in two ways, by putting<br />

constituents in brackets, as in (32), or by drawing a tree diagram, as in (33). The two notations are<br />

equivalent to each other.<br />

(32) [[[English language] degree ] [entrance requirements ]]<br />

16

(33)<br />

English language degree<br />

entrance requirments<br />

In point of fact, a compound such as English language degree is ambiguous, because it<br />

can have a different constituent structure. A degree in language (e.g. in French) taught in England<br />

could also be called an English language degree (as in the expression ‘people studying English<br />

language degrees often go to Europe for language practice, but people studying American<br />

language degrees usually can’t afford to’). In this case the constituent structure would be (34):<br />

(34) [English [language degree ]]<br />

PROBLEMS OF DEFINITION<br />

We come finally to some more theoretical questions concerning morphology. We shall limit<br />

ourselves to problems of providing definitions for some of the technical notions we have been<br />

using.<br />

The first problem is this: we can isolate many morphological processes in a language, but<br />

in general only some of them are actively used to form new words, or make new word forms. For<br />

instance, no new abstract nouns are ever formed using the affix -th (as in warmth, health, etc).<br />

However, new nouns can be freely coined using an affix such as -ness or -ity. Likewise, when a<br />

new verb enters the language it is always given regular inflections. The noun ring was converted<br />

into a verb to ring meaning ‘to form a ring around’ or ‘to put a ring on’, as in ‘the police ringed<br />

the demonstrators’, ‘the ornithologist ringed the guillemots’. However, even though the verb to<br />

ring in the sense of ‘to cause a bell to sound’ has a past tense rang, the past tense of the converted<br />

verb is regularly formed from -ed.<br />

This problem is referred to as the problem of productivity. Some morphologists claim<br />

that only productive processes should be studied by linguists and regarded as ‘real’ morphology;<br />

the unproductive processes would then be regarded as historical accidents (rather like spelling<br />

conventions are an historical accident). Other morphologists claim that the unproductive<br />

17

processes are just as much part of our grammar as the productive ones and that the question of<br />

productivity has more to do with psychology than linguistics.<br />

The next problem is ‘how do we define the term “morpheme”?’. The standard definition is<br />

‘the minimal linguistic sign’ or ‘the smallest unit of meaning’. There are problems with both the<br />

‘meaning/sign’ aspect and the ‘unit’ aspect.<br />

Given that some morphological processes involve phonological changes rather than<br />

affixation or compounding, what do we mean by ‘unit’? In other words, how do we say that the<br />

Ablaut in man-men or sing-sung, or the stress shift in 'transfer-trans'fer is a morpheme? Different<br />

theories have different ways of resolving this, but no approach is accepted even by the majority of<br />

researchers.<br />

The problem with ‘meaning’ is simply that there are some units which we would like to<br />

call morphemes but which don’t have any meaning. The standard examples involve different<br />

types of berries:<br />

(35) a. cranberry<br />

b. loganberry<br />

c. huckleberry<br />

The problem is that cran-, logan-, and huckle- have no meaning. Yet berry means exactly what it<br />

should do in (35). Moreover, cran- etc. must contribute something to the meaning of the word as<br />

a whole, otherwise the examples in (35) would all mean the same (or would be all meaningless).<br />

A morpheme of this type which has no identifiable meaning is called a cranberry morpheme (I<br />

leave the reader to deduce the etymology of this term).<br />

The Latinate vocabulary of English provides interesting examples of this kind of thing.<br />

The verbs of (36) and (37) are all bimorphemic. But what is the meaning of each of these<br />

morphemes?<br />

(36) receive, deceive, conceive, perceive<br />

(37) a. refer, remit, relate, resume<br />

b. defer, decide, depose, define<br />

c. confer, commit, compose, confine, consume, collate<br />

d. permit, perplex, perfect, perform<br />

Morphology is the study of morphemes and also of words. When we come to defining the<br />

notion ‘word’ we encounter serious difficulties. First, we must distinguish several technical<br />

18

senses of the ordinary language term ‘word’. In one sense the examples of (38) are all different<br />

words.<br />

(38) sing, sings, singing, sang, sung<br />

In another sense they are all forms of the same word, namely forms of the verb sing. In the first<br />

sense, we will use the term word form. In the second, more abstract, sense we will use the term<br />

lexeme. Thus, (38) are all word forms of a single lexeme SING. It is the lexeme sense of ‘word’<br />

that we mean when we ask ‘how many words of English do you know?’. If you knew the<br />

grammar of English but only one verb, sing, and you claimed to know five verbs by virtue of<br />

knowing (38), you’d be cheating. Likewise, if you claimed to know 36 words of French, simply<br />

by knowing how to conjugate the verb parler.<br />

There are five ways of analyzing the French word parle. It may be the 1st or 3rd sg.<br />

present indicative or the 1st or 3rd present subjunctive or the sg. imperative. If we only take<br />

pronunciation into account (/parl/) we would have to add 2nd sg. present indicative and<br />

subjunctive, 3rd pl. etc. This means that for one lexeme we have a single word form (e.g. parle)<br />

which has many different morphosyntactic descriptions. In a sense, then, parle is a single word<br />

form of a single lexeme, which nonetheless represents several words. The words in this latter<br />

sense we will call morphosyntactic words. English provides examples of the same phenomenon.<br />

For instance, the word walked is simultaneously the past tense form and the past participle form.<br />

The form runs is simultaneously the 3rd sg. of the verb run and the plural of the noun run.<br />

Even with these subtle definitions it is not always easy to know what a word is in a given<br />

language. We have already mentioned compound words. Are these words in the same sense that<br />

words like run and walk are words? Or do we need to distinguish between ‘real’ words and<br />

compound words? If so, do we say that the -wife of housewife is a word or not? Likewise, what<br />

about -man of postman. (It is interesting to note that this -man is pronounced with a reduced<br />

vowel, a schwa, rather than the full vowel of the proper word man.) In many languages affixes<br />

evolve over the centuries from compounded forms such as postman. This has happened with<br />

English words like like which has now become an affix in words such as in life-like. Perhaps -<br />

man is becoming an affix rather than a real word? How can we tell when the process is complete?<br />

Some rules of phonology seem to refer to words, for example stress rules governing the<br />

position of main stress. But often the types of words defined by phonology are different from<br />

those defined by morphology or syntax. For instance, in English a definite article attached to a<br />

noun is generally not stressed. This makes it look like a part of the noun, from a phonological<br />

point of view. We call such combinations phonological words. But a phrase such as the apple is<br />

19

a phrase, not a word, from the morphological and syntactic point of view. For instance, we can<br />

interrupt it with another word or phrase: the [very green] apple.<br />

This notion of ‘interrruptibility’ is a criterion often used to distinguish phrases<br />

(interruptible) from words (not interruptible). In point of fact, it’s not always easy to apply it.<br />

Interpreted strictly it would have the undesirable consequence of entailing that infixes such as<br />

Tagalog s-um-ulat or English fan-bloody-tastic are impossible. In the ‘apple’ case above, it is<br />

easy to see that very green is not an infix, so there is no problem. In other cases, it may not be so<br />

easy.<br />

There is a fascinating problem in morphology related to the notion of phonological word.<br />

This is the problem of clitics. What would you call the pronominal forms in the following French<br />

expressions? Words? Affixes? Something else?<br />

(39) a. Jean me le donne John gives it to me<br />

b. Donne-le-moi ! give it to me<br />

Linguists call them something else, namely clitics. These are elements which seem to be like<br />

independent words but which don’t have the same distributional freedom as real words, that is,<br />

they are restricted to appearing only in certain parts of the sentence. French pronominal clitics can<br />

appear either before the verb (in which case they are called proclitics) or after the verb<br />

(enclitics). Moreover, they are unlike words in that it is impossible to put another word (other<br />

than a clitic) between two clitics. This makes them look like affixes. In some languages, however,<br />

it is clear that the clitics are not affixes because they don’t attach to a particular category of word<br />

(such as the verb), rather, they attach to a word or phrase in a particular position in the sentence.<br />

In Czech and Serbo-Croat, for instance, the clitics always come after the first constituent of the<br />

sentence, whether it is a noun, verb, adjective or whatever.<br />

English doesn’t have pronoun clitics of the French variety, though words such as the<br />

articles, personal pronouns (especially in the object form) and monosyllabic prepositions all tend<br />

to have the phonological properties associated with clitics, i.e., they don’t receive a stress of their<br />

own and therefore can’t easily exist on their own. Instead, they like to have another word to attach<br />

to (the word ‘clitic’ itself is derived from a Greek word meaning ‘to lean’).<br />

Andy Spencer December, 1987<br />

Cornelia Hamann March, 2005<br />

Recommended Reading: Fromkin, V., R. Rodman and N. Hyams (eds.) (2003). An Introduction<br />

to Language. Chapter 3, Morphology.<br />

20