The Light Makers - Alby Chrisbach

The Light Makers - Alby Chrisbach

The Light Makers - Alby Chrisbach

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong> ©<br />

<strong>Alby</strong><br />

<strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

A Round Table Story

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong> is<br />

81, a seasoned story-teller and<br />

alone on Earth in 2999. In<br />

1945, when <strong>Alby</strong> was 17, he<br />

had moved to Los Alamos.<br />

His dad had been hired to<br />

work as a machinist at <strong>The</strong><br />

Labs. <strong>Alby</strong> witnessed the<br />

first atomic blast, the Trinity<br />

Test. It terrified him. A<br />

new material was formed by<br />

the blast. <strong>Alby</strong> discovered<br />

it, enabling an adventure<br />

of time-travel. He wanted<br />

to preclude the development<br />

of nuclear technology. He<br />

travels back in time to meet<br />

Einstein, Oppenheimer and<br />

Teller in 1941 at Columbia<br />

University and considers<br />

some of the cultural issues<br />

behind the creation of the<br />

bomb.<br />

<br />

“No faculty of the mind is as pure as friendship;<br />

it is our only rightful claim to decency.”<br />

— Mark Isaac Rabinowitz<br />

✑<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> tells the story<br />

of a murder that occurs<br />

within this group of notables<br />

that grows to include young<br />

Beat poets and writers, who,<br />

along with the physicists,<br />

suggest a series of practical<br />

and egalitarian technologies.<br />

<strong>The</strong> murder investigation<br />

is interlaced with some<br />

advocated technologies,<br />

<strong>Alby</strong>’s time-travel and a<br />

stream of quips and queries<br />

from the physicists and poets.<br />

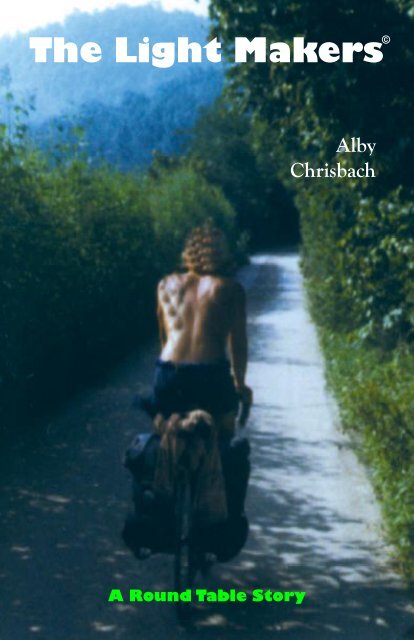

Front Cover Photo:<br />

Mark Rabinowitz, July 1941,<br />

riding up to Mount Kisco<br />

on the newly paved Albany Post Road.<br />

Mark made the bike frame and the rack.<br />

Marcia Rabinowitz made the saddlebags.

✑<br />

✑<br />

© Copyright, 1998 by <strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

United States Copyright Office Registration # Txu 884-696, November 18, 1998. All rights<br />

reserved. Duplication or publication of this document, conventionally or electronically, is not<br />

permitted. This story is a work of fiction. <strong>The</strong> characterizations of four well-known physicists,<br />

four well-known poets and other notables are fictional. Any possible association to any real<br />

person or event is coincidental.<br />

alby@albychrisbach.com

Chapters<br />

~ Illustrations ~<br />

PRELUDE ................................................................... 9<br />

~ THE FAMILY, SUCH AS THEY ARE IN 1941 ~ ................... 12<br />

~ THE OTHERS, AS WE SHALL MEET THEM... ~ ................... 13<br />

ST. JOHN THE DIVINE .................................................. 15<br />

SINING THE STONE ...................................................... 25<br />

~ THE 57TH PARALLEL ~ ............................................ 44<br />

FROM LATVIA WITH LUCK ............................................... 45<br />

~ MORNINGSIDE HEIGHTS ~ .......................................... 64<br />

THE STEPS ............................................................... 65<br />

~ NEW YORK GLOSSARY ~ .......................................... 84<br />

THE ROUND TABLE ...................................................... 87<br />

CHILDREN OF MANHATTAN ........................................... 109<br />

~ COTTAGE YACHT MOCKUP ~ ................................... 119<br />

BICYCLING, ATOMS & POETRY ...................................... 131<br />

~ THIS IS JUST TO LAUGH ~ ........................................ 136<br />

~ THE IDEA OF ORDER ON THE DELAWARE ~ ................... 150<br />

COMMITTEES TO DIE FOR ........................................... 155<br />

MOLECULAR MECHANICAL CALCULUS ............................. 181<br />

DIAMONDS ARE FOR NOW .......................................... 195<br />

FISSION IS FOREVER ................................................... 205<br />

FEAR OF LEAVES ....................................................... 217<br />

HAMMOCKS OF BROWNSTONE RAVINE ............................ 225<br />

TRAILS & TRIALS OF DECEIT ......................................... 231<br />

A HANGING ............................................................. 245

A Round Table Story<br />

Prelude<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

✑<br />

My name is <strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong>. I am 81 now, born in 1928. I have<br />

been alone for 12 years. I have become, inadvertently, a time-traveler.<br />

It would be 2009 in my timeline, although an atomic clock that I found<br />

recently indicates it is 2999. Before me is a natural paradise that bears<br />

greatest resemblance to my perception of the forests of a pre-technical<br />

era, possibly five or six thousand years ago. <strong>The</strong>re are few buildings<br />

standing in this former Santa Barbara and those are deeply covered<br />

in layers of white, orange and purple-flowered vines. I am dreadfully<br />

frightened to sine the stone again since it has been through this abuse<br />

that I may have eliminated all people and our handiwork of civilization.<br />

Yes, I am alone, except for my dear dog, Tarigo, and myself.<br />

I am a thin man, abstemious in habit, often delirious with<br />

hunger. My hair is now white and remains thick and long; for many<br />

years beyond my expectation it was brown and wavy. In a few timelines<br />

I have been thought to be mystical because of my endless hunger<br />

and because of my dark eyes that linger inappropriately in study and<br />

stare. I believe the characteristic that is the strongest in me — and the<br />

one that has transcended time the most graciously — is empathy. It<br />

has nearly cost my life more than once, but I have honed this skill to<br />

a point where some thought I could read minds. In these, my aging<br />

years, in this grotesque peace of loneliness, I have come to be able to<br />

read time as well as the openings toward it. With the directness of a<br />

gale-force wind I yearn for some minds to meet again, some minds to<br />

merge with, some minds to understand.<br />

I consider it so very unlikely that any of this will ever be read.<br />

It appears that human life no longer exists. I am well aware that, if<br />

you were to exist, your perceptions might be entirely different from<br />

mine — that is, if you somehow were to acquire a copy of this journal<br />

from my future. I am also aware that there may be other powers at<br />

play here, as my friend Leon had suggested when we were students. I<br />

may well be dead. I may be in a dream. I may be autistic or a savant<br />

of some kind, and you may be there, but I may be blind, deaf or in a<br />

coma. I cannot be positive of who I am and of the events that I will<br />

describe. I can only tell you that which I perceive. I imagine that when<br />

people were alive, back then, that the only truth that anyone could<br />

really tell is the truth of their own perceptions, including their own<br />

various distortions of their experiences and interpretations. <strong>The</strong>se,<br />

humbly, are mine.<br />

9

Prelude<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong>se are neither tales of science fiction nor of science speculation.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se are the stories of the feelings and conclusions of some<br />

of the people I have met in my time-travels, people that I had come<br />

to have known intimately. I miss these people greatly and it is their<br />

stories that I must tell. I have several stories all-in-all, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong>,<br />

this series of little tales that includes the story of a terrible murder that<br />

deeply saddened other tragedies in this community. Another story is<br />

about Metallic Hydrogen and Neutronium, called Metallic Hydrogen.<br />

This story tells of the dramatic cultural effects of time-travel, only a<br />

few of which are found in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong>. I tell a story of timelines<br />

called <strong>The</strong> Bell Tower.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a plethora of print reproduction equipment about,<br />

since the evidence of life remains in many places. It is always necessary<br />

to cut great vines and remarkably dense growth to access this or<br />

any other equipment, such as communications devices, which I seek<br />

often, but always, to no avail. Prior to sining the stone again, a dangerous<br />

process that I shall explain in another chapter, I take pleasure in<br />

reproducing some copies of these texts. I will release them in random<br />

times unknown to me with the hope that you might exist, and that you<br />

are capable of reading. If you can read it is possible that your influence<br />

will alter the distortions of time and place that I believe I have<br />

caused. If these distortions do not occur, then this book might not<br />

be written, a number of technologies may disappear, and, with luck,<br />

humanity will persevere.<br />

With the direction our species has taken, it now seems so unlikely<br />

that additional time-travel will be able to restore life to earth. I<br />

am going to indulge myself in these tidbits of tales that have interested<br />

me rather than supply you with a technical manual for reversing the<br />

dissolution of mankind. If I were to write such a manual, I would<br />

inaccurately call it ‘Weapons Dissolution Methodologies,’ or some<br />

other pretentious title — perhaps ‘<strong>The</strong> Egalitarian Development.’<br />

<strong>The</strong>se stories, however, are not about weapons or utopias. I have tried<br />

every possible technique to generate this reversal for 12 years without<br />

success, and remember, it is I who possesses the power of the stone.<br />

If restoration is to occur, it must occur through the real power, your<br />

power, the power of human desire to quell exhibitions of arrogance<br />

and the barrenness of ruthless greed.<br />

I have spent many years mastering the correct swing of my<br />

leather pouch and pea-glass. It isn’t a trivial task to achieve the correct<br />

sine wave to go to the correct time and place. I know now that<br />

you must treat each motion as seriously as an Olympic discus thrower,<br />

10<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

several of whom I trained with in order to develop the strength and<br />

grace to bring my weighty pea-glass into pattern. I have acquired many<br />

journals, letters and ships’ logs to help tell these tales with accuracy,<br />

and all-in-all, have treated both time traveling and story-telling quite<br />

seriously.<br />

Ω<br />

11

~ <strong>The</strong> Family, such as they are in 1941 ~ ~ <strong>The</strong> Others, as we shall meet them... ~<br />

Chaim Scheckman<br />

Ishmael and Lara Scheckman<br />

Key:<br />

Bold Major Character<br />

Italic Minor Character (included for perspective)<br />

Blank No appearance<br />

Doralyn - 58<br />

Daniel - 66 Horace - 70 Jared - 58<br />

Vladimir & Faye Weinstock<br />

Peter Dennis Ronnie<br />

Heshie Rabinowitz - 67<br />

Gladys - 64<br />

Rusty - 43 Richard - 43<br />

Mark Isaac - 39 Marcia - 39<br />

Roy - 31<br />

Moisha - 34<br />

Sally - 27<br />

Jeffrey - 17<br />

Jonathan - 19 Joshua - 13<br />

Anthony Bruno<br />

Major Characters<br />

Anthony Cinelli Bishop, Mark Isaac Rabinowitz’s best friend<br />

Patrick Londonderry Policeman then Detective, assigned to Chief Shawnessy<br />

Spoon O’Reilly<br />

Priest, Assistant to Bishop Cinelli<br />

Jeremy Davidson Community Poet and Panhandler<br />

Benjamin Poinstein Real Estate Developer<br />

Stumpo Stagnoli Detective, assigned to Chief Shawnessy<br />

Mikey Martinelli Detective, assigned to Chief Shawnessy<br />

S. S. Shawnessy Chief of Police, leading the investigation<br />

Georgey Rinato<br />

Mayor of the City of New York and friend of Londonderry<br />

Eileen Bechsler<br />

Jonathan Jeremy Rabinowitz’s girlfriend<br />

Albert Einstein<br />

Physicist<br />

Edward Teller<br />

Physicist<br />

Robert Oppenheimer Physicist<br />

Jack Kerouac<br />

Writer<br />

William Burroughs Poet & Writer<br />

Allen Ginsberg<br />

Poet<br />

Manolo Ramirez Naval Architect, Mechanician, Anthropologist, Ethnographer<br />

Amalayus Harraka Former Scheckman Paint Factory Foreman<br />

Nicky Fozzoni<br />

Benjamin Poinstein’s Lieutenant<br />

Barry Leverman Engineering Student at Columbia<br />

Enrico Fermi<br />

Physicist<br />

Rahim Markowitz Owner of Berkeley’s Shfvitz next to ‘<strong>The</strong> Labs’<br />

Minor Characters<br />

Leon<br />

Smart college friend of mine<br />

Rob<br />

Childhood friend of Mark’s - Next Door Neighbor<br />

Andrew<br />

Friend of Joshua Rilke Rabinowitz<br />

Mrs. Krauck<br />

Building Superintendent at 116 th & Riverside<br />

<strong>The</strong> Avalon Family Rabinowitz family friends from Mount Kisco, New York<br />

Lyndon Rich<br />

Clairmont Fuckademy Headmaster<br />

Trent<br />

Friend of Jonathan Jeremy Rabinowitz<br />

Pauli Prito<br />

Mafia Leader from Staten Island<br />

William Carlos Williams Physician & Poet<br />

Professor Bechsler<br />

Eileen’s father, Barnard Professor, 2 nd home near Los Alamos<br />

General Leslie Groves Manhattan Project military leader at Los Alamos<br />

Mickey<br />

Friend of Jeffrey Scheckman<br />

Sharon<br />

Secretary to Richard Scheckman<br />

Mrs. O’Neil<br />

Receptionist at Napa Winery<br />

Spaulding<br />

Chardonnay Club Tennis Player<br />

Darryl Hammacher District Attorney<br />

Roger Berlini<br />

Attorney for the Defense<br />

Julius Hoffman<br />

Young Judge<br />

Henry Barnes<br />

Traffic Commissioner of New York City<br />

Dr. Levinthal-Lipman Forensic Psychiatrist<br />

Serge Inglentomena Building Superintendent at an East Side Hotel<br />

<strong>The</strong> Steel Family<br />

Avalon and Rabinowitz family friends from Mount Kisco<br />

12 13

St. John <strong>The</strong> Divine<br />

✑<br />

Joshua Rilke Rabinowitz, a blond-haired Jew, and his best friend<br />

Andrew, a red-headed Catholic, were high up where no one should<br />

go in St. John <strong>The</strong> Divine, the Manhattan Cathedral on Amsterdam<br />

Avenue and 112 th Street. From their perch, the 13 year-olds viewed the<br />

largest nave in the world, larger than the Vatican. On this Sunday in<br />

1941, midway between the birthday of Jesus Christ, and, as the story<br />

goes, his commemorative day of resurrection on Easter Sunday, the<br />

Day of the Harps was celebrated only at St. John’s. This holiday was<br />

conceived by the charismatic and remarkable Father August, whose<br />

real name was Anthony Paul Cinelli, and whose real title was that of<br />

Bishop. As a devotee of St. Augustine, Bishop Cinelli said repeatedly,<br />

“Do few things and do them well.” He said it so often that people<br />

thought he was getting senile. He had been saying it since he was 10,<br />

when Joshua’s grandfather, a Jewish-Latvian furniture maker, told him<br />

this favorite phrase of woodworkers, and that it was St. Augustine who<br />

said it first. “Do few things and do them well.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> endearing and kind Father August was 6’ 4”, strongly featured<br />

with exotic black eyes and shiny black hair. He was a sensitive,<br />

lightly sarcastic leader, often genuinely funny and strong enough to help<br />

the sculptors move stone. He absolutely refused to be called Bishop.<br />

He didn’t want to be thought of as above his congregation. Instead he<br />

insisted he would be with his congregation, part of it, intimate within<br />

the community. Anthony Cinelli was so important to Catholic New<br />

York — and his Church so important to Christianity in general — that<br />

the Cardinals and Bishops of the Archdiocese of New York met at St.<br />

Patrick’s just to discuss this issue. Two years prior, in 1939, they made<br />

a compromise and summoned Bishop Cinelli by limousine: Anthony<br />

Cinelli would be known as Father August, after his mentor, St. Augustine,<br />

the urban utopian visionary. Anthony Cinelli was thrilled. He<br />

considered this to be the greatest honor of his splendidly honored life.<br />

That evening he put on cut off sweat pants and a T-shirt and spun his<br />

way through nearby Central Park on his Cinelli bicycle, complete with<br />

a full set of Campognola parts. He did 5 laps, or 25 miles.<br />

Andrew, a classmate of Joshua Rabinowitz’s at Fieldston, just<br />

over the bridge in Riverdale — the lowest part of the Bronx — had<br />

worked on this one for awhile. He knew that Father August was best<br />

friends with Joshua’s dad, since he had seen him at Joshua’s house<br />

many times. <strong>The</strong> Rosary Beads and Cross that Father August wore<br />

had been hand carved by Joshua’s grandfather, Heshie Rabinowitz,<br />

15

St. John <strong>The</strong> Divine<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

out of rosewood, teak and zebrawood. <strong>The</strong>y were very large Beads, far<br />

larger than anyone had seen on a clergyman before. <strong>The</strong>y scaled well<br />

on very large Anthony Cinelli. <strong>The</strong>y fit his frame, and elevated him<br />

mysteriously. <strong>The</strong> large, handcarved zebrawood cross, fluid in form,<br />

large enough to be suggestive of a man with a burden had been rubbed<br />

lovingly by hand.<br />

Andrew, like everyone who knew the activities of Morningside<br />

Heights, knew that the Day of the Harps was fast approaching. If he<br />

and Joshua could get up into the nave, somewhere high, they would be<br />

able to see and hear the entire event without a bunch of lying adults to<br />

bother them and yell at them. Andrew was skilled with his dad’s camera<br />

and was pretty creative, and thought if he showed Father August some<br />

of his pictures they might be able to get high up in the nave. This was<br />

also the best place to check out the girls’ boobs — from above. Father<br />

August, the eccentric man of the Church who gave sanctuary to many<br />

for political reasons, and who sometimes filled the grounds and the<br />

floor of the church with the poor, appreciated Andrew’s photography<br />

and agreed to the scheme. He told the boys to see Father O’Reilly for<br />

access to the hidden stairs, “Spoon’ll help ya.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> Day of the Harps was an orchestra performance of 100<br />

Harps. <strong>The</strong> endless echoes of the string sounds were so unique that the<br />

holiday on Morningside Heights became more important than Easter<br />

itself. 100 Harps. Only in Manhattan could you find 100 harps, and<br />

the charismatic Father August got them there, year after year, and he<br />

filled the church, year after year. St. John’s was a significant place not<br />

only for music, but also for architecture, art, childcare, care for the aged,<br />

care for the homeless, care for the sick. <strong>The</strong> building was an ongoing<br />

construction project with sculptors and masons employed year round.<br />

Volunteer sculptors came from Carrara in Italy to climb the scaffolds<br />

and carve for St. John’s. Bronze sculptures suddenly appeared on the<br />

grounds. Rooms were built overnight in the basement as if carved directly<br />

from Manhattan’s speckley gray schist by God Himself. It was an<br />

honor to work for Catholic Bishop Anthony Cinelli, Father August, of<br />

the Episcopalian St. John <strong>The</strong> Divine. Although generally inconceivable<br />

for a leader of one religion to head the church of another, in this<br />

case, both Catholics and Episcopalians were thrilled to have Anthony<br />

Cinelli in this position.<br />

On February 23, 1941, Sunday, the Day of the Harps, when<br />

Andrew and Joshua were given access to the hidden nave stairs by<br />

Father Spoon O’Reilly, Father August was not in New York. Father<br />

16<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

O’Reilly warned the boys to be careful and not make any noise while<br />

they were up in the nave, and insisted on a complete set of pictures<br />

after they were developed. Andrew’s father’s Nikon impressed him<br />

as it impressed me. <strong>The</strong> camera was of the new single-lens reflex type<br />

that enabled you to see in the viewfinder the same image that would be<br />

captured on the film . Quick-responding mirrors on springs enabled<br />

this technology. Andrew had four Nikkor lenses. A round Cardinal<br />

opened the service shyly, said little and announced that Father August<br />

had been called to Rome. <strong>The</strong> audience murmured impolitely, missing<br />

Father August and his raucous jokes and funny improprieties. After<br />

all, a Catholic running an Episcopalian monument cannot persist<br />

without humor.<br />

<strong>The</strong> talented harpists played Bach, Vivaldi and Beethoven.<br />

Young Leonard Bernstein conducted. <strong>The</strong> boys snapped through two<br />

rolls of film. While the harps played the boys lay on the floor looking<br />

down in complete amazement, with an overhead, commanding view.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y studied the 100 harps and 100 harpists in black-tie and low cut,<br />

white-gowns. <strong>The</strong>y appreciated the string sounds that could not be<br />

heard elsewhere on Earth. During the first intermission, Andrew<br />

looked out over the new construction site and at the picture of the<br />

new building, the old age home that would be built across Amsterdam<br />

Avenue. <strong>The</strong> first floor had been poured, and columns added to later<br />

support the second story. On either side of the future entrance of the<br />

building the columns were very thick, as if they were going to support<br />

a giant marquee and cantilevered floor sections. Something on the<br />

top of one of the columns looked familiar. It was in the concrete, now<br />

dry, floating in and out of the top of the column.<br />

“Hey Joshua, can things float in concrete, on the top of it?”<br />

“You mean when it’s wet?”<br />

“Yeah.”<br />

“Sure, I think it’s like water, stuff floats. When we put our<br />

hands in wet concrete, it’s always real wet. I guess the water gets pushed<br />

to the top and other stuff could float up with it.” Joshua didn’t think<br />

anything of the question, but during the second session, he knew that<br />

Andrew wasn’t listening to the harps.<br />

During the second intermission, Andrew went back to look<br />

at the column.<br />

Joshua followed, “What’s wrong?”<br />

Andrew, “Look at the big column closest to us, on the top of<br />

it, what do you see?”<br />

Joshua, “A rope or something.”<br />

17

St. John <strong>The</strong> Divine<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

Andrew, “No, look again.”<br />

Joshua picked up the camera, “Put on the big lens.”<br />

Andrew did, and gave Joshua the camera. Andrew put his<br />

head between his knees.<br />

Joshua focused, with difficulty, and said, “Hey those are Father<br />

August’s Beads, I wonder why he threw them there, maybe to give them<br />

to the poor or something like that.”<br />

When Joshua took his eye off the camera to give it to Andrew,<br />

he heard Andrew crying with his head still between his legs. “Suppose<br />

he’s in there, suppose Father August is in that column?”<br />

“Don’t be stupid, Andrew, you heard the Cardinal say Father<br />

August is in Rome.”<br />

“No, don’t you be stupid, asshole. Father August would never<br />

throw away those Beads and he would never miss the Day of the Harps<br />

or this whole weekend.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> boys didn’t hear much of the finale of the harps. <strong>The</strong> playing<br />

went on without them. <strong>The</strong>y were sweating. <strong>The</strong>y were alone at<br />

a bad time, as if locked in a closet like terrorized children. When the<br />

joyful crowd poured out of all of the doors it still took another hour for<br />

Andrew and Joshua to get Father O’Reilly’s attention. <strong>The</strong>y insisted<br />

he accompany them up the hidden stairs. <strong>The</strong>y looked panicked, but<br />

Spoon didn’t presume to guess the reason.<br />

Andrew said, “Look at the thick column by the garbage dumpster,<br />

to the right of it, look at the top of it.”<br />

Joshua said, “Here, look through the camera.”<br />

Spoon O’Reilly’s systems began to close down. His throat was<br />

collapsing. His eyes were filled with water. He was feeling his upper<br />

stomach cramp, acidic gas tearing at his upper chest. “We must get<br />

the Cardinal, please, you go, tell him that if he would be so kind, to<br />

please accompany you up the stairs to see me. Say nothing to no one.<br />

Be sure to kiss his ring, both of you.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> Cardinal was the perfect grandfather, much like my own.<br />

He patted the heads of the boys and followed them quietly. Up the<br />

stairs, slowly, more stairs — the camera. <strong>The</strong> image of the Beads in<br />

the concrete was too much for the Cardinal. He needed water, he<br />

needed to sit down, he needed to leave St. John’s and get air. <strong>The</strong><br />

Cardinal asked the boys to get the police, since neither Father Spoon<br />

O’Reilly nor the Cardinal could move. <strong>The</strong> Cardinal instructed them<br />

to explain nothing, just to come to see him, and to bring the police<br />

upstairs. Spoon and the Cardinal stared at the column through small<br />

clear pieces of clear glass known as lights in the magnificent stained<br />

18<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

glass windows. A 45” square column of concrete was encased in lumber<br />

before them.<br />

∞<br />

Father August — Bishop Anthony Paul Cinelli — had been<br />

missing since early Friday evening. Spoon had looked everywhere,<br />

they had asked everyone. He knew that something was very wrong<br />

almost immediately. Bishops didn’t abandon their staffs and friends<br />

and jobs and students and miss appointments and special holidays.<br />

Was Anthony complaining about anything? No. Was there a warning?<br />

No. Anthony had said last week that some meetings were tough,<br />

lots of shouting. No big deal. This was New York. People shout all<br />

the time. Ad Hoc Morningside Planning Group, Friends of the Park,<br />

Urban Shelters, Air-Rights Allocations Committee, Crisis of the Aging,<br />

St. Luke’s Children’s Wing Committee, and more. Just meetings.<br />

Andrew and Joshua ran out to find a cop. <strong>The</strong>y ran to<br />

Broadway. It was crowded, too many people. Andrew shouted at the<br />

panhandler, Jeremy, “where’s a cop?” Jeremy pointed. <strong>The</strong>y ran. He<br />

screamed up the street after them,<br />

“<strong>The</strong> yellow beast sat on the bomb,<br />

Though no smart beans are beasts.<br />

You sloppy banana boys,<br />

You are beasts to steal my beans.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>y found Officer Patrick Londonderry, and hurried him up<br />

the hidden staircase. Spoon was down and about and had already sent<br />

for the limousine. He yelled at the boys to get in, and gave the driver<br />

Joshua’s address. He knew it well; he had been to Round Table dinners<br />

with Father August. Spoon was greeted warmly by Marcia Rabinowitz,<br />

who was certain that the boys had done something terrible, since there<br />

was no other reason why her son and his friend would be ushered<br />

home by Father O’Reilly mid-day. <strong>The</strong> brief story in low tones in the<br />

doorway sickened Marcia, just the thought of it. Spoon took her to<br />

the couch. She ran to the bathroom, heaving. Anthony Cinelli had<br />

been her dear friend since she had first met Mark. Anthony was the<br />

godfather of her children.<br />

Spoon assured them not to jump to conclusions. Marcia sat<br />

with the boys for 15 minutes or so, and they seemed to be OK. Everyone<br />

was too scared to cry, faces were red, sweating. She wasn’t OK,<br />

so she went back to the kitchen. Andrew came into the kitchen and<br />

19

St. John <strong>The</strong> Divine<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

asked if Joshua could come with him while he went home to tell his<br />

mom. “Fine, go.” She was coming apart. She felt it. To collapse on<br />

her bed, to cry hard, to get Mark, Mark who was in Princeton for the<br />

day. Christ. Fuck. No. It’s not happening, no.<br />

<strong>The</strong> boys ran out of the elevator, down Riverside, up 115th<br />

Street, down Broadway to 112th Street. <strong>The</strong>y ran across Broadway<br />

and sprinted down 112th to Amsterdam. About 20 policemen were<br />

there, about half on horseback. A great number of short and beefy<br />

men were getting out of a few pickup trucks, and picking up air hammers<br />

from even more mysterious confines of these few trucks. A large<br />

compressor on the site was started. <strong>The</strong> site foreman was shouting<br />

orders. Several men in suits were getting out of cabs. One man was<br />

one of the building’s owners, developer Benjamin Poinstein, of this<br />

newest old age home. <strong>The</strong> other was his Project Manager, the Owner’s<br />

Rep on the job. Others in suits looked like detectives and spoke into<br />

car radios. <strong>The</strong> boys went close to the action so that Father O’Reilly<br />

and the Cardinal wouldn’t see them. Spoon and the Cardinal were<br />

sitting across the street on folding chairs in front of the enormous<br />

bronze doors of St. John’s, doors that told stories of life and death in<br />

detailed reliefs. More frocks of undetermined position surrounded<br />

the seated men.<br />

To open a construction site on Sunday afternoon — to gather<br />

the owners and contractors almost instantly — should be an impossibility<br />

in any timeline. In this case, the site was opened in less than<br />

hour, with most players present. A murder of a Bishop in Catholic<br />

New York? <strong>The</strong> construction industry, especially concrete, is very Mafia<br />

and very Catholic. This Cathedral is incredibly important in New<br />

York. When Officer Londonderry understood who might be in the<br />

column, he didn’t call his precinct first — in violation of all protocols<br />

and orders. He called his childhood friend from PS 109 in Queens,<br />

now Mayor Georgey Rinato, at his temporary home at Gracie Mansion.<br />

“Why Jesus fuck goddammit does this have to happen in my<br />

New York in my goddam administration.” Mayor Rinato screamed,<br />

then shouted, then rolled the ball. He told the City Controller to<br />

prepare to enable financing for twenty detectives and officers to work<br />

on the disappearance and possible murder of Bishop Anthony Cinelli.<br />

“Fucking Anthony Cinelli, god damn this City.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> wood forms were removed from the column from the recent<br />

pour, slow piece by slow piece. Scaffolding was erected completely<br />

around the column and enclosed entirely with drop cloths. Short,<br />

thick men with small air hammers ushered their air hoses into the<br />

20<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

scaffolding and up. <strong>The</strong> noise began. Within 5 minutes, there was so<br />

much dust the noise stopped, the short men talked to the tall super,<br />

who talked to Chief of Police S.S. Shawnessy. <strong>The</strong> drop cloths were<br />

removed. Whatever was to be seen would be seen by all. For decency,<br />

the short, bullish men worked as much as possible on the west side of<br />

the column, the back, chipping away at the somewhat fresh concrete.<br />

Within 25 minutes an air hammer man screamed a very deep, dark<br />

sound, almost a growl. Blood had squirted on his face and chest. <strong>The</strong><br />

air hammering stopped. Another man wiped his face, and took him<br />

down and off the site. He was shaking like the air hammer he had<br />

just dropped. His face carried the fear of a gargoyle.<br />

<strong>The</strong> crane from the site started up. <strong>The</strong> hammering began<br />

again, with men chipping low, close to the first floor pour. A welder<br />

was cutting the double-tied steel rebars. Other men were up higher<br />

tying chains around the column. A flatbed truck was pulling up to<br />

the site on Amsterdam. <strong>The</strong> crane rose upwards and cranked to<br />

tighten the chains on the column. <strong>The</strong> hammering continued, and<br />

in another 25 minutes, all but the foreman left the scaffold. He tied<br />

3 more special ropes to the column that other men held. He went to<br />

the opposite side, raised his air hammer, hammered for 2 minutes,<br />

and the upper section of the column was freed. <strong>The</strong> crane operator<br />

cranked away immediately, spun the concrete block out toward the<br />

street, and the men with the ropes guided the column section above<br />

the flatbed. Within a few minutes the round column was lowered to<br />

the flatbed, chocked, covered and chained. <strong>The</strong> presumed entombed<br />

body of Father August was driven to a place unknown. <strong>The</strong> crowd<br />

dispersed, quietly aware of who might be in the concrete. <strong>The</strong> reporters<br />

and cameramen blended into the scene. <strong>The</strong>y would be mauled if<br />

they were rude. <strong>The</strong> construction site was boarded up, and “Closed<br />

by Order of Mayor Rinato and Chief of Police Shawnessy,” each with<br />

a hammer in hand, tacking up the Order with angry faces that made<br />

them look like sheriffs tacking up ‘Most Wanted’ posters. Good for<br />

the front-page, though.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ice-solid Hudson River drove the winter winds of Riverside<br />

Drive with Chicago-like forces. For many weeks after Father August’s<br />

death, anger dominated many circles in New York. <strong>The</strong> Rabinowitz’s<br />

were devastated. Mark Isaac Rabinowitz, Joshua’s father, had been<br />

Anthony Cinelli’s best friend since childhood. Heshie and Gladys<br />

Rabinowitz, Joshua’s grandparents, took the train up from Princeton<br />

to see if they could help, and they worked with the folks at St. John’s,<br />

21

St. John <strong>The</strong> Divine<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

and cooked, and brought food. <strong>The</strong> Avalon’s came down from Mount<br />

Kisco. <strong>The</strong> Episcopalian congregation of St. John’s was demonstrating<br />

daily, demanding police action and threatening vigilante action.<br />

Other angry parties included the Episcopalian Ministry, the general<br />

community of Morningside Heights, the Archdiocese of New York,<br />

<strong>The</strong> Catholic Church in Rome, <strong>The</strong> Catholic Italian community both<br />

in New York and Sicily, the construction community in New York and<br />

the Mafia in both New York and Sicily. <strong>The</strong> Mafia gave the police two<br />

weeks, then said they were going to handle it after that. It would be<br />

the Weekend of Hope that the police would first investigate.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Weekend of Hope at St. John <strong>The</strong> Divine consisted of<br />

Friday, the Day of Disclosure, Saturday, the Day of Remembrance,<br />

and Sunday, the Day of the Harps.<br />

On Friday evening the World Disasters Travelling Show from<br />

the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies<br />

put on a $50 per plate dinner. A play that dramatized natural and<br />

man-made disasters was presented. Jonathan, Joshua’s older brother,<br />

had been one of the authors since he was 14. <strong>The</strong>re is no problem<br />

getting material. Each year 15 to 20 million are made homeless. <strong>The</strong><br />

extent of annual human tragedy is incomprehensible.<br />

Saturday, <strong>The</strong> Day of Remembrance, was a clothes and cannedgoods<br />

drive in the morning, distribution in the afternoon and a festive<br />

free buffet dinner for the needy in the evening. No one went home<br />

until he or she was stuffed and pockets were filled with cans. Skits were<br />

repeated daylong and jugglers and mimes became silly and near-delirious<br />

with the repetition. Panhandler Jeremy didn’t miss a thing. His<br />

disheveled beard and notably clean hair merged in a brown enormity<br />

as if he had just woken from a million year nap and stepped through<br />

the glass of a caveman display in the Museum of Natural History 30<br />

blocks south. He helped load trucks the evening before, and on Saturday<br />

made as many trips with as many cans to as many hiding places<br />

as any trained urban survivor could, regardless of the anthropological<br />

era from which he might have come. To a smiling lady handing out<br />

canned peas, he limericked,<br />

22<br />

“It not can not, I not be not,<br />

We not feel not, you not see not.<br />

I see can, yes I,<br />

I saw Father, yes I,<br />

Know not sleep not, I not tell not.”<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> cross-eyed, quiet lady shook her index finger at Jeremy as<br />

if to scold him for denying her the flying reptiles and flying fishes that<br />

normally occupied his speech. I handed Jeremy two cans of carrots;<br />

we stared in silence. My table was next to the lady’s table of peas.<br />

My broken leg was somewhat painful, and beginning to itch; I wasn’t<br />

smiling as instructed. In my most recent time-warp I had acquired<br />

this broken-leg through an arrival on the edge of a platform. My pod<br />

rolled from it onto a concrete floor in an abandoned warehouse in<br />

Clifton, New Jersey. I tied up my leg the best I could with some nearby<br />

package cord. I crawled to a window, broke it, and shouted for help.<br />

I left my pod there on Kulick Street. Passaic General Hospital set my<br />

leg and set me free.<br />

∞<br />

Sunday of the Weekend of Hope was the Day of the Harps<br />

and the day of the discovery of Father August. If there was an opportunity<br />

present in this murder to turn the other cheek and end the<br />

vengeance cycle that so devastatingly traumatizes our species, it was<br />

not going to be exercised with this murder. This was a time for an<br />

eye for an eye. People were pissed. Chief Shawnessy was personally<br />

in charge of the investigation, and he updated Mayor Rinato and the<br />

newspapers daily.<br />

Mark Isaac Rabinowitz was the hardest hit personally by Anthony<br />

Paul Cinelli’s death. He mourned in his own way, silently, alone<br />

in his office at home. He saw the face of his friend as a gigantic image<br />

taking up the entirety of his vision, larger than any movie screen,<br />

larger than his own peripheral vision. Anthony’s image maintained its<br />

projective force for 8 days, and then, it was locked only into the corner<br />

of his vision, small, but present. In this time, Mark Isaac hadn’t slept.<br />

He dosed in his chair, briefly, and not in a bed.<br />

Mark Isaac then slept for 2–1/2 days, in bed this time, unaware<br />

of his dreams, getting up, drinking, peeing, smiling at his family if<br />

they were up, and when it was over, it was over. Mark Isaac got hold<br />

of himself, ate well, returned to his schedule and heralded his family<br />

and immediate community back to life, as Anthony Cinelli would<br />

have demanded. “Let’s drive up to Mount Kisco, all of us, and thank<br />

the Avalon’s for their help.” <strong>The</strong>y drove up the Albany Post Road<br />

that Sunday, to acknowledge first spring and put the terrible death of<br />

winter behind them.<br />

23

St. John <strong>The</strong> Divine<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

A few trees began to bloom in the weeks that followed, and the<br />

gray snow and black speckled slush began to melt. A few light snowfalls,<br />

white and beautiful, a few hot days, more blooms, more smiles.<br />

As the spring-gentle robins chirped the tree buds to life, Mark Isaac’s<br />

grief grew to anger. He was more than curious to learn what luck the<br />

police had in their search for the murderer.<br />

24<br />

Ω<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

Sining the Stone<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

As a boy in grammar school I had learned that indoor plumbing<br />

had been developed during the Roman Empire. I wondered sincerely<br />

how and why technologies sometimes came and went. With the<br />

power of time-travel in my hands, I was able not only to witness such<br />

changes, but also to cause them. I wondered if I could help Mark to<br />

find Anthony’s killer. In the absolute sense I never intended damage to<br />

anyone, and I even believed that I could fool with the timeline enough<br />

to preclude the development of nuclear weapons.<br />

Having inadvertently introduced the bicycle in the mid 1750’s,<br />

the transportation system of the timeline of my childhood had been<br />

changed. By the 1870’s roads were paved and cars honked and maimed<br />

their way through busy streets. Other technologies, fashions and trends<br />

developed earlier because of my intervention, but my critical mission<br />

was to identify and stop, if possible, the timeline that developed the<br />

nuclear technologies and their spin-offs, Metallic Hydrogen and Neutronium.<br />

Through sining the stone I tried to fix whatever inequities I<br />

understood, such as anti-Semitism, since I am half-Jewish myself. I<br />

believe that at least in Princeton, New Jersey I was able to accomplish<br />

this reversal. I found myself studying a group of Catholics and Jews<br />

who were socially close to several of the inventors of the bomb in the<br />

days preceding the Manhattan Project. Most of what I learned about<br />

these people was at the time of Anthony’s death. It is through this<br />

mysterious and entirely alarming murder that you will learn of these<br />

frenzied, frantic, desperate people. Some are weak and ineffective,<br />

some besieged by self-destruction, some besieged by greed, and others<br />

whose malevolence is carefully disguised behind their careers.<br />

Most of what I learned about these people, of their good and<br />

bad, has been at the Rabinowitz Round Table. It was a fine table,<br />

certainly, but it was the overt fashion in which this group thrust their<br />

exaggerated dysfunctionality upon everyone which caught my attention.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y did it with an abrupt frankness that reminds me of the days<br />

of verbal culture, far before mass media and even book publishing. I<br />

was there at the time, became a friend within this very community of<br />

nudniks, notables and geniuses and went as far as breaking and entering<br />

to acquire the journals of those who kept them. It is strange to<br />

me now that while alone on this planet I find this particular process<br />

of story telling to be so fulfilling. Looking at the incursion of growth<br />

around me, throughout Santa Barbara — a former tourist town on the<br />

25

Sining the Stone<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

Central Coast of California — and at the devastation of other places<br />

I used to visit, I cannot believe life as I have known it will emerge<br />

again. In my loneliness, as some seek a god, I have romanticized beings<br />

beyond. Most of the time I do not believe that the life forms of<br />

other planets would be in the least way humanoid even if they had an<br />

interest in our vegetation and seas, and somehow, an interest in the<br />

gadget mentality to develop space travel. <strong>The</strong> likelihood of a creature<br />

from another planet possessing any communicative abilities seems<br />

impossible. Such lifeforms would look more bizarre to us than cockroaches<br />

or dinosaurs, and their communication forms would be about<br />

as different. I therefore have no false expectation that the world I may<br />

have destroyed by trying to save will find a magical resolution from<br />

space. In that sense, there is no hope. It is in the sense that you in<br />

your timeline might read this journal of my timeline that represents<br />

the only hope I can fathom.<br />

∞<br />

<strong>The</strong> buildings of these years have collapsed. <strong>The</strong> reinforcing<br />

bars in the concrete have all rusted and the concrete floors and walls<br />

fell under their own weight. <strong>The</strong> roots of time have stitched their paths,<br />

weaving this forest floor. Its fruits are my only foods. <strong>The</strong> streams<br />

from the transverse mountain range of Santa Barbara are my secret<br />

joy. You will see in these stories items out of your time, since I have<br />

changed time. Which items they may be depends on your timeline,<br />

which I cannot know. <strong>The</strong> minor distortions will not distract you; the<br />

stories of murder, of tragedy, of genius, and of obsessive greed will be<br />

fully recognizable since these have followed us through all the timelines<br />

I have encountered.<br />

I do not believe in magic or miracles and I certainly don’t believe<br />

in unfounded popularisms like astrology. Yet, as you know, there<br />

is the unexplained. On one timewarp I learned some techniques in<br />

biofeedback with a Dr. Fred Lorenz of Davis, California. I found that<br />

I could raise the temperature of an ear or a hand, and lower the temperature<br />

of the other ear or hand at the same time. I learned to drop<br />

my heart rate down to 20 beats per minute. I learned to stretch out<br />

between two chairs with my head on one and my heels on the other.<br />

A 200-pound man sat on me with no appreciable effect. I learned to<br />

swim long-distance butterfly, and swam 4 miles of this stroke without<br />

stopping, every week for a year. On the other days of the week I swam<br />

4 miles of backstroke, or breaststroke, or freestyle and then combinations<br />

of those strokes. As I swam I studied the patterns on the bottom<br />

26<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

of the pool, and occasionally let my body continue to swim on the<br />

surface while I went to play in the more interesting patterns along the<br />

bottom. It is a treat to look up at yourself and see your stroke. It is<br />

the patterns alone that provide the tour.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is little doubt that the most dramatic art form of the<br />

mind and body enhancing skills that I learned with Fred Lorenz is<br />

dream-hopping. Some skills of biofeedback — such as creating alpha<br />

waves to make you more calm or beta waves to simulate mathematical<br />

thinking — are rather simple to master. Mastering the theta wave is<br />

not easy at all, this, the needed skill to dream-hop. <strong>The</strong>ta is the brain<br />

wave that is commonly generated by artistic people in the height of<br />

creativity or by athletes in endurance swims or runs. This phenomenon<br />

occurs most frequently while working in the middle of the night. I<br />

labored with the long, gray-haired Dr. Lorenz to master this last skill,<br />

to generate theta waves at will.<br />

Dr. Lorenz worked with me until my skillset was quite high.<br />

Besides learning to swim, I was able to correct my vision to 20-20. I<br />

learned to withstand unusual heat and cold since I could adjust the<br />

temperature of my skin. I kept working on the theta wave challenge,<br />

and once made the electroencephalograph chime and several components<br />

in the array of lab equipment beep and chirp. <strong>The</strong> moment<br />

was excruciatingly painful. I tore the electrodes from my head, burst<br />

from the inner, glass-walled observation chamber, stormed through<br />

the white lab-coated technicians working at the black-slate counters,<br />

charged through the doors and sprinted about ten miles to my time<br />

pod. I fell to its side. And slept.<br />

And slept. And dreamt of quiet Mark Rabinowitz, who<br />

was awake, so I left him. And I dreamt of the deeply caring Marcia<br />

Rabinowitz, who was asleep, and who I visited. Oh, how this woman<br />

cared for so many, how she was in such perfect synchronicity within<br />

her culture. So many nights when I hopped into her dreams did my<br />

own pillow become soaking wet with tears of her later pains, wet with<br />

the empathy which has besieged my paltry existence. Marcia’s plight<br />

overwhelmed me, and the sadness of her experience penetrated not only<br />

time but place. Here, approaching the year 3000, I cry uncontrollably<br />

for a woman dead more than 1000 years. Not once in my life did I<br />

dream-hop to find the mind of a dullard. Always there were struggles<br />

in each person’s dreams, struggles, less creative or more creative attempts<br />

to explain life. What I like most about dream-hopping is that<br />

the otherwise rigid walls of up-time do not exist, and each transcends<br />

his imagery throughout all timelines. This is most exciting since for<br />

27

Sining the Stone<br />

28<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

many decades I have been the only time-traveler depending entirely<br />

on dream-travel for emotional substance.<br />

∞<br />

I have aged normally with little damage despite the suddenness<br />

of some of the temporal shifts. I have come to know the feelings of<br />

some of the people that I have dreamt with along the way, and have<br />

time-traveled to meet. Some people I have come to know intimately.<br />

I have met some of these people deliberately, since I am almost always<br />

on one of my sophomoric missions to change the events of history. I<br />

make as few changes as I can, focusing on the significant issues. Some<br />

changes appear harmless. Others have been ultimately tragic.<br />

Several times when I was really alive — when there were others<br />

in my life — my apparent empathy made people ask if I was a Social<br />

Psychologist. No one has ever asked if I were a Cultural Anthropologist,<br />

although this is primarily how I have seen myself even during<br />

these lonely years, a barren observer of three dimensions trapped by<br />

circumstance in the fourth dimension of my own making.<br />

Empathy has magically produced employment for me when<br />

needed. I acquired jobs as an investigative reporter. It was easy for<br />

me to sense what was going on in a busy newsroom, and to enter the<br />

dreams of those I met during the day. In subsequent days I could say<br />

expected phrases to land permission to submit articles. This skill of<br />

‘extended-empathy’ and this trade of investigative reporting has been<br />

dangerous, although I became increasingly careful over the years. I<br />

thought I knew when to leave a time or a place — that is, until 12 years<br />

ago.<br />

∞<br />

You will meet a great many people in this story and wonder, as<br />

I have wondered, what has become of them. Time travel leaves behind<br />

an unfortunate barrenness that plants question marks every inch along<br />

every timeline. I cannot eliminate these real people and I cannot leave<br />

them nameless. <strong>The</strong>y were there. What I know of them, I must tell<br />

you; I cannot simplify the interwoven nature of a community. <strong>The</strong> few<br />

names that you must know, you will know. <strong>The</strong>se are the Rabinowitz’s<br />

— Mark, Marcia, Jonathan and Joshua. You will not be able to forget<br />

the good Anthony Cinelli. If there was anyone special and worth<br />

knowing it would be Jeremy Davidson.<br />

Anthony Cinelli’s murder begins only four years before I found<br />

the pea-glass, the stone. It begins in a place that I tried to find for five<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

real years of my life. It is not easy to master time warps, contrary to<br />

science fiction. I have referred to sining the stone as warping time. It’s<br />

more like warping a place. To get to the right place at the right time<br />

takes, well, time. And risk. Once I found myself with my legs growing<br />

out of solid rock. I wasn’t in pain. <strong>The</strong> rocks had grown around me. If<br />

my upper body had not been free to swing my pouch, to sine the stone,<br />

I would have died in place. I surmised that the place for time-travel<br />

would be in orbit, so the earth wouldn’t suddenly be mountainous<br />

beneath me. I also imagined that if I were in orbit, the earth might<br />

glide away from me as time changed. I never left the planet surface;<br />

I couldn’t figure out how to enter space. One time I caused a rogue<br />

wave to emerge from the middle of a quiet ocean and found myself<br />

miraculously washed aboard a rocking ship with a Swedish crew in a<br />

terrible panic. Had that ship, the Skara, not been there, I would have<br />

surely drowned. I avoided the ocean on all future time-travels.<br />

∞<br />

I brought some of this future to another past. <strong>The</strong>se anomalies<br />

can be seen since you will notice historical distortions that vary<br />

according to your own timeline. It is best if you complete an experiment<br />

now so that you can understand the issue of time. If you have<br />

never made a Mobius Strip before, I urge you to do this now. If you<br />

do not, you will find these stories lacking. This experiment is quite<br />

necessary. Please gather a regular sheet of 8 1/2” x 11” paper, tape<br />

and a pen. Making a Mobius Strip assures you that not everything<br />

is as straightforward as it appears, and the things that you hold to be<br />

self-evident may not be so. This experiment is far from a trick. If you<br />

do not make the Mobius Strip yourself, now, you will only smirk your<br />

way through these tales.<br />

Fold the paper back and forth several times along its length,<br />

less than one inch from the side. Score it with your thumbnail. Tear<br />

carefully along this scored line. Keep the thin strip and discard the<br />

large remaining sheet. In kindergarten you learned to tape the narrow<br />

ends together to make a ring. Do the same thing, but give it a half-twist<br />

— not a full-twist — before taping it. Tape it carefully on both sides so<br />

it doesn’t fall apart.<br />

Please do not presume that I am leading you astray. Aside<br />

from my experience with time-travel you would find me to be a quiet<br />

old man who is a realist, a man whose memory is intact, and a man<br />

who greatly respects the passion of youth. I know clearly that the loop<br />

29

Sining the Stone<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

that I have made has two sides, as does yours. I can see both sides;<br />

so can you. With the loop in my hand I can feel the dual surfaces of<br />

the twisted ring, and can almost squeeze them. Side one is next to our<br />

thumbs and side two is next to our index fingers. Fine. Our twisted<br />

ring has two sides. Let’s try to prove this.<br />

With a pen, begin drawing a line anywhere on the strip.<br />

Continue in the same direction always extending the line further and<br />

further. What has happened? You haven’t switched sides with your<br />

pen line, yet the pen line met up with itself. <strong>The</strong>re are two sides to<br />

the Mobius Strip, one next to your thumb, and the other next to your<br />

index finger. Yet, at the same time, there is one side to the Mobius<br />

Strip. You have traced it with your pen. <strong>The</strong>re are two sides. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

is one side.<br />

This contradiction is similar to that of time, at least as far as I<br />

understand it. It is perhaps the contradiction of the universe itself, and<br />

possibly the contradiction of our cultural and economic structures. On<br />

one side of our strip, on the ‘have’ side, our need for creature comforts<br />

is huge. We sacrifice all ethical ideas for a system that provides these<br />

comforts. <strong>The</strong> other side, the ‘have-not’ side, is not important to us in<br />

our desire for comfort; it is the side we actively forget. However, as you<br />

have determined, your two-sided strip has only one side. It is the same<br />

side at all times. <strong>The</strong> line is continuous; it represents a continuum.<br />

An ethical culture would flow as this continuum, through you in your<br />

life to generations beyond. Either ideation flows with consistency or<br />

with contradiction. Many believe that the ‘have-nots’ live on the other<br />

side of the tracks. But they don’t. <strong>The</strong>y live on the only side.<br />

∞<br />

With luck and your efforts humanity will persevere, and I in<br />

my efforts will disappear. If it were not for the finality of annihilation<br />

in what the military called a ‘Nuclear <strong>The</strong>ater,’ I may have been more<br />

conservative in my exploitation of Metallic Hydrogen. Knowing of<br />

the possibility of global annihilation has made it prudent for me to<br />

attempt to prevent it. Prudent, I thought then, but now I fear that it<br />

may have been I who has caused such annihilation through my timetravels.<br />

I cannot know this, and it is only self-serving to even mention.<br />

At least, it cannot be excluded. As of this writing, I know human<br />

life stopped. How it stopped, and if it can be reversed, are for other<br />

Round Table Stories.<br />

Ahead you will feel the woes of the whining, sad environments<br />

that characterize nouveau-riche and puerile-academic attitudes. You will<br />

30<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

taste greed, and see greed intertwine even within the brilliant. You<br />

will experience the ultimate arrogance, the consideration of global<br />

holocaust.<br />

∞<br />

It first happened when I was 17. I grew up in an Italian and<br />

Jewish neighborhood in Paterson, New Jersey. My mom was Jewish<br />

and my dad Italian. <strong>The</strong> neighborhood was loud and it was fun. We<br />

had little clubs. Our club was ‘<strong>The</strong> Cobra’s.’ We had jackets with felt<br />

patches with a green embroidered snake. Very cool. We had bows<br />

and arrows, and shot at each other without fear. Sometimes there was<br />

blood. One kid lost a finger with firecrackers. Another was stabbed<br />

in the toes in a knife game called chicken. I won that game, ‘cause I<br />

was the kid who got stabbed. We liked to shoot arrows at ‘<strong>The</strong> Warriors’<br />

the most, because they were mostly nebishes. I hated school, and<br />

liked sex. <strong>The</strong> neighborhood was pretty funny, and I have provided a<br />

glossary to help you with those special words of that timeline.<br />

Dad was a machinist milling airplane components. One day<br />

in 1945 he came home and said we’re moving to Los Alamos, New<br />

Mexico, wherever that was. I was the middle kid, a thin slice of bologna<br />

between two older brothers and two younger brothers. I was unusually<br />

quiet until I was about 14, and if I talked, no one listened. I wrote a<br />

lot then, and I guess that’s why I’m writing now.<br />

I never even completed one course at Santa Fe Junior College<br />

in New Mexico. I registered for Anthropology, Physical Education,<br />

Dance, Philosophy and Flying. My Anthropology teacher was beautiful,<br />

about 23, and also my flight instructor. We had an airport right<br />

on campus. I loved flying as much as I loved girls. Lots of girls. In<br />

Philosophy I sat between some lovelies. Young Mr. Higginbotham<br />

noticed them, too, and directed most of his lectures directly at us, at<br />

the girls and me. He held up a pencil. “Is this pencil really here?”<br />

“Yes,” answered a pretty one.<br />

“Of course,” I answered.<br />

“No,” answered some kid named Leon Wiesel from the other<br />

side of the room, “I perceive a pencil to be in your hand, but I do not<br />

know, in fact, if it is in your hand. I may be entirely misperceiving,<br />

and furthermore, I may be alone in this room, and furthermore there<br />

may be no room and no school and I might be just a fantasy emanating<br />

from a rock.”<br />

Smirks spread.<br />

31

Sining the Stone<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

“A priori,” Leon said, at which point I alone laughed condescendingly,<br />

accusatorily and loudly at Leon. It was my policy to laugh<br />

at anyone who said ‘a priori.’<br />

“I think, therefore I am,” Leon continued, trying successfully<br />

to impress Mr. Higginbotham, whose favorite word was ‘predicated.’<br />

I hated school.<br />

Leon’s dad and Mr. Higginbotham’s dad worked at ‘<strong>The</strong><br />

Labs,’ too, up the hill at the old Los Alamos Ranch School for Boys.<br />

General Leslie Groves was in charge of the entire complex. Gigantic<br />

explosions were taking place up there. Leon was 16, and would probably<br />

go off to Harvard. I was flunking 3 out of 5 courses at Santa Fe.<br />

I was doing well in gym, and great in flying. <strong>The</strong>y wouldn’t let me<br />

in the Army because I was a little too tall and a little too skinny and<br />

had a little too much asthma. Dad got me on at <strong>The</strong> Labs, but only<br />

after school. He got me on as a General Laborer working for a New<br />

York developer. I was entirely pissed that I couldn’t get into the Army<br />

because Pearl Harbor violated me as it violated everyone else. I was<br />

glad that at least <strong>The</strong> Labs were a real part of the War Effort and that<br />

I was part of <strong>The</strong> Labs.<br />

You see, I didn’t mean to do it. Once I understood that I might<br />

not be able to master time-travel after all, I did it only a few more times,<br />

at first. Until I realized that everything was already so different, that<br />

it wouldn’t matter if more things changed. So I did it more. And I<br />

didn’t really believe I was the only one making changes. I suddenly<br />

found myself remembering what my friend Leon had said. To this day,<br />

I think of Leon and realize that I may be insane, and that I may not be<br />

alone in this time sphere. It appears that I am alone, and therefore I<br />

must write this in the event that you might see it when again I warp<br />

time by sining the stone. I must do it again to give these stories to you.<br />

I promised myself that I wouldn’t sine the stone so often, that I might<br />

destroy everything, even animal life, although I may have destroyed<br />

everything already, and I don’t know it. Yes, I will do it one more time<br />

only to distribute these stories.<br />

∞<br />

My flight instructor and I were airborne at the time of the<br />

first big mushroom-cloud bomb explosion, the Trinity Test. We were<br />

still hundreds of miles away, returning from a package-exchange with<br />

another complex, also called ‘<strong>The</strong> Labs’ in Berkeley, California. We<br />

had planned to spend the weekend with friends in Berkeley, but had<br />

a fight with them in an all-night conversation. Our friends objected<br />

32<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

to the work at the Berkeley Labs and at the Los Alamos Labs. We<br />

defended our families. We took to the air. It was a quiet, calm day.<br />

<strong>The</strong> flight was uneventful until about 5:30 in the morning. <strong>The</strong> date<br />

was July 16, 1945. <strong>The</strong> blast was inconceivably huge, visible everywhere,<br />

spherical and other-worldly. We thought we felt the heat. <strong>The</strong><br />

disturbed air knocked us free of controlled flight. We were spun full<br />

around and thrown into a dive. My instructor was not only beautiful,<br />

but talented. She pulled us right out of the spin. I liked the feeling<br />

of the dive. I get hard when I free fall, and when I jump from heights<br />

at every quarry and from every tree.<br />

We started to fly toward the blast, toward home, but several<br />

aircraft found us and warned us away. If the United States could drop<br />

bombs like that we would win the war — for sure. It was completely<br />

amazing to see. It also terrified me. I suddenly thought that it represented<br />

an incomprehensibly dark side of man. An anger festered.<br />

This ‘weapon’ wasn’t something that could be used against ships or<br />

planes, but something that would only be used against cities, and in<br />

cities, most people are innocent. <strong>The</strong> bomb was devastating. I didn’t<br />

like this bomb and I was starting not to like <strong>The</strong> Labs and my dad. I<br />

also heard that the Army shot holes through local ranchers’ water towers<br />

to harass them into leaving the area prior to the Trinity Test. <strong>The</strong><br />

Army couldn’t understand why families who ranched the area would<br />

want to enjoy their homes.<br />

About a month after the blast our crew was told to go to the<br />

Trinity Site — about 120 miles south of Los Alamos near the town of<br />

Bingham in the Alamogordo Bombing Range. This area had been<br />

named Jornada del Muerto, Journey of Death, by Spanish explorers<br />

hundreds of years earlier. <strong>The</strong> area lived up to its name. We were doing<br />

roadwork and replacing road signs. We were creating a false path<br />

to a false bombsite on the wrong mesa. This was necessary, we were<br />

told, to keep the curious from getting close.<br />

My crew was closest to the real site, what they called ‘Ground<br />

Zero.’ We were covering up the real road. When the foreman took<br />

off to check on another crew, I took off to go check out Ground Zero.<br />

<strong>The</strong> foreman had warned us to stay away and not go near the bombsite<br />

because we would get sick and die, so I ran around the site like I was<br />

doing laps back at Eastside High in Paterson. I was running about a<br />

two-mile lap around the hole. When I saw the shiny glass I just ran<br />

by it on my first lap around. I passed it again and stared at how clear<br />

and bright it was. Much of the sand had been turned to glass by the<br />

33

Sining the Stone<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Light</strong> <strong>Makers</strong><br />

fierce heat of the blast, but the piece of glass that I saw was clear and<br />

perfect looking, a diamond, I hoped. When I saw it on the third lap<br />

I picked it up. Rather, I tried to pick it up.<br />

I figured that it was part of a larger boulder, and didn’t think<br />

anything of it. I kept running. A few hundred yards later I saw another<br />

piece of clear glass that was very small, the size of a pea. I picked it<br />

up, but it weighed about 20 pounds. I ran back to the guys, who were<br />

lying in the shade. In the truck I found a small leather pouch with a<br />

long cord used by a survey instrument. I went back for the pea-glass.<br />

I decided to hide my find, slinging the strap of the small pouch onto<br />

my shoulder as I ran up the side of a hill. I didn’t want my moron<br />

crewmates to see me with my pea-glass, either, and chose a steep but<br />

hidden route up the hill. I climbed fast. I took one step onto the very<br />

top. It happened to be at the actual perimeter edge of the mesa. <strong>The</strong><br />

weight of the pea-glass took my balance. I fell into the air at this very<br />

edge. I was sure I would die, but I didn’t panic. I thrilled in the fall.<br />

I just like the feelings you get in those free-falls. I spun myself around<br />

and around. I fell into a lake.<br />

∞<br />

Falsifying the location of Ground Zero took some tricky road<br />

work. For Dr. Robert Oppenheimer and Dr. Edward Teller this was<br />

harder and more wrought with complications than the theoretical<br />

posturing and jousting required in the calculations of atomic physics.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hillsides of the Journey of Death were snaked with dirt roads,<br />

now radioactive, and the ranchers, ranch families, ranch hands, local<br />

Indians and the curious had to be kept at bay.<br />

Only Dr. Oppenheimer, Dr. Teller and the construction crew<br />

risked visiting Ground Zero after detonation. <strong>The</strong> radiation was<br />

high. <strong>The</strong>y didn’t know about protection suits back then and argued<br />

with their peers that a visual inspection was necessary and that they<br />

alone should go. <strong>The</strong>y reported back that, as expected, the soil had<br />

been turned to glass and Little Boy’s drop-tower had been vaporized.<br />

‘Little Boy’ was the name of their first bomb. That name bothered me.<br />

<strong>The</strong> name rang of a sick presumptiveness; it foreshadowed a ruthless<br />

arrogance, a magnitude of horror for which our languages have not<br />

provided the vocabulary and our philosophies have not provided the<br />

concept.<br />

<strong>The</strong> atomic doctors did not report back to their peers that there<br />

was a small hole in the ground of the exact size of the core device itself.<br />

34<br />

A Round Table Story<br />

<strong>Alby</strong> <strong>Chrisbach</strong><br />

Sized exactly the same as a soccer ball, the dark hole went straight down<br />

into the earth. <strong>The</strong> walls of the hole, too, had turned to glass.<br />

To assemble discreet crews to do construction requires money,<br />

and the more money paid the more discretion you believed you were<br />

buying. <strong>The</strong> enormous pressure of actually producing this bomb was<br />

overwhelming to everyone, but no one internalized as much pressure<br />

as Dr. Oppenheimer, in charge of scientific development. He dropped<br />

a rock in the hole. It clinked. He dropped another, and he and Dr.<br />

Teller, with a stopwatch, estimated the hole was about 250’ deep.<br />

That’s where the product of the nuclear implosion was, 250’ beneath<br />

the surface. <strong>The</strong>y had a problem.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was no way to justify to the government that digging a<br />

250’ hole was appropriate in order to examine the soil. <strong>The</strong>y didn’t<br />

want anyone from the Manhattan Project close to the soccer ball,<br />

which they told everyone would be the first thing to vaporize. In fact,<br />

it would be the center of the implosion and it would not be vaporized.<br />

It would be recreated into a huge diamond due to the thick carbon<br />

lining of the soccer ball, and possibly, interior to the diamond surface,<br />

would be Metallic Hydrogen.<br />

Dr. Oppenheimer or Dr. Teller never expected this deep hole.<br />

Although they speculated that the device would be driven downwards<br />

by the explosion, they estimated the hole would be about 5’ deep.<br />

Now, at 250’, they knew it was Neutronium that caused the ball to<br />

drop through the glassing soil. If there was any of the highly desired<br />

Metallic Hydrogen, a material thought to be able to warp space — and<br />

therefore time and place — it would be a thin layer of egg shell surrounding<br />

the Neutronium.<br />

∞<br />

Through Dr. Oppenheimer’s journal and that of a paint factory<br />

foreman I can tell you how I came to find the stone. Richard<br />

Scheckman, a Manhattan real estate developer, had opened an office in<br />

Albuquerque, and was overpaying his crew — substantially overpaying<br />

them. <strong>The</strong>y built a few projects at a loss, although he told his wealthy<br />

friends the New Mexico projects were successful. <strong>The</strong> books were done<br />