Understanding historic park designs - HELM

Understanding historic park designs - HELM

Understanding historic park designs - HELM

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

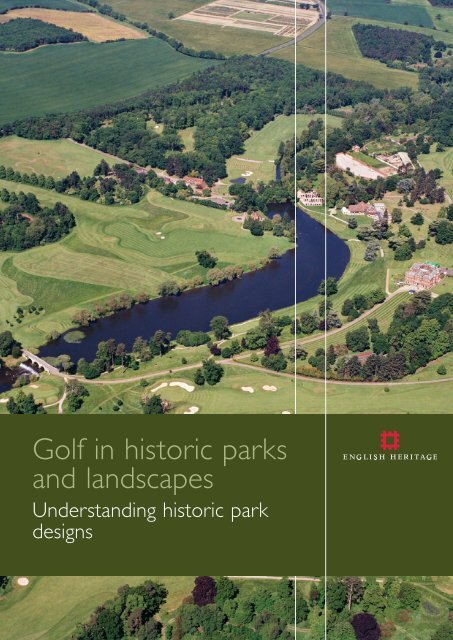

Golf in <strong>historic</strong> <strong>park</strong>s<br />

and landscapes<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>historic</strong> <strong>park</strong><br />

<strong>designs</strong><br />

4

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>historic</strong> <strong>park</strong> <strong>designs</strong><br />

Introduction<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> the <strong>historic</strong>al development of a site, its features and characteristics,<br />

will help shape golf course <strong>designs</strong> or modification of existing courses. Most <strong>park</strong>s<br />

are the product of more than one <strong>historic</strong> design phase, and expert advice is<br />

generally needed to unearth the evolution of a <strong>park</strong> from its origins to the present.<br />

Historic importance can derive from a site being an early or representative example<br />

of a style of layout, type of site or the work of a designer of national importance; or<br />

from having an association with significant persons or events; or from having group<br />

value with other nearby sites.<br />

Types of <strong>historic</strong> <strong>park</strong><br />

Deer <strong>park</strong>s (late Saxon period to the 1640s)<br />

Creation of deer <strong>park</strong>s reached a peak in the 13th and 14th centuries but continued<br />

into the 17th century, when many were dis<strong>park</strong>ed in the Civil War and<br />

Commonwealth period. The <strong>park</strong>s were often not directly attached to a principal<br />

mansion, but often had some kind of lodge.<br />

Principal features:<br />

• Generally either wood pasture, with trees and grass intermixed or<br />

compartmentalised with separate grassland and woodland blocks<br />

• Archaeological remains of <strong>park</strong> features such as <strong>park</strong> boundary or pale,<br />

woodbanks, fishponds, warrens, lodges<br />

• High levels of ecological interest stemming from traditional grassland<br />

management and veteran trees (generally oak, lime, beech and sweet<br />

chestnut, and almost invariably pollarded in the past, and others such as<br />

hornbeam and hawthorn).<br />

Formal <strong>park</strong>land (1650s–1720s)<br />

Up until the Civil War the primary function of <strong>park</strong>s was deer management and<br />

hunting. After the war, new country houses and <strong>park</strong>s were developed and these<br />

<strong>park</strong>s were increasingly ornamental and used for agriculture and forestry.<br />

Continental influence both before and after the war encouraged a strong degree of<br />

formality and geometry.<br />

1

Fig 1 Deer grazing at Bushy Park, West London, a 16th-century deer <strong>park</strong> with formal<br />

avenues added in the 17th century.<br />

Principal features<br />

• Avenues of trees ranging from single approach avenues to extensive<br />

networks, often aligned on a focal point either within the estate (such as a<br />

lodge) or outside (such as a church spire)<br />

• Main approach and sometimes a secondary approach for deliveries and farm<br />

access; development of lodges; hard-surfaced (hoggin or local gravel) drives –<br />

other avenues were simply grassed for riding<br />

• Formal gardens around the principal building with geometry often linked to<br />

the <strong>park</strong>land planting<br />

• Geometric water features<br />

• Plantations, usually geometrical in outline and sometimes laid out in quasimilitary<br />

formations<br />

• Dominant linear views down the avenues plus lateral views over the estate<br />

(whether <strong>park</strong>land or farmland, grazed or arable) which would also have been<br />

an important part of their enjoyment.<br />

2

The landscape <strong>park</strong> (1730s–1800)<br />

From the early 18th century onward there developed a distinct English landscape<br />

aesthetic gradually overtaking the more formal aesthetic of the previous century.<br />

The key features of the English landscape style developed under Lancelot ‘Capability’<br />

Brown from the mid-18th century onward, although Brown often incorporated<br />

elements of mature formal planting in his <strong>designs</strong> rather than ‘sweeping’ it away. The<br />

whole was designed to give the impression of a natural landscape that could be<br />

appreciated particularly through the carefully composed series of views encountered<br />

during movement through the <strong>park</strong>land on the main approach and the ridings.<br />

Considerable ingenuity and earth-moving went into Brown’s <strong>designs</strong> to create<br />

naturalistic vistas and to hide unwelcome features, such as the surface of the<br />

approach in views from the house. Many of these compositions are vulnerable to<br />

erosion by neglect or subsequent planting so that expert analysis is often required to<br />

identify them correctly.<br />

Principal features<br />

• Informal clumps of trees, single trees and woodland<br />

• Perimeter belts and rides<br />

• Irregular, natural-looking water bodies<br />

• Entrance drives and carefully contrived drives and rides<br />

• Informal but composed views from the main approach, from ridings around<br />

the <strong>park</strong> and from the house’s principal rooms and entrance<br />

• Designed views to eyecatchers such as a purpose-built structure or folly<br />

within the <strong>park</strong>, a clump of trees planted on a distant hill top or a<br />

neighbouring building<br />

• Ridings often extended outside the <strong>park</strong> into the surrounding estate to<br />

include views of farmland and more distant beauty spots<br />

• Ideally the house appeared to rise directly from the landscape <strong>park</strong>, but more<br />

often than not shrubbery walks or other discreet garden areas continued to<br />

be valued in the near neighbourhood of the house with kitchen gardens<br />

hidden out of sight<br />

• Tree planting in <strong>park</strong>land largely used a restricted palette of predominantly<br />

native trees, such as oak, lime, beech and sweet chestnut, with only<br />

occasional use of exotics such as Cedar of Lebanon – specialist plantations of<br />

American and other exotic trees became increasingly popular towards the<br />

end of the 18th century<br />

• Plantations grown for timber, with oak extremely popular for its economic<br />

and symbolic value<br />

3

• Perimeter planting mixed fast-growing species such as scots pine with the<br />

slower growing hardwoods<br />

• Sporting use of the <strong>park</strong> dictated the need for game-cover, with laurel, box,<br />

and broom frequently planted as an understorey in woodland.<br />

Fig 2 Stowe, Buckinghamshire, a highly influential landscape <strong>park</strong>.<br />

The ferme ornée (1740s–90s)<br />

The ferme ornée was a notable variation on the landscape <strong>park</strong>, affording landscape<br />

<strong>park</strong> features on a small scale and combining landscape compositions with a working<br />

farm. Most purely ornamental features and planting would be located around the<br />

perimeter route.<br />

Principal features<br />

• A perimeter ride or walk partly or wholly within a belt of planting of shrubs<br />

and trees<br />

• Views inwards from the perimeter across mixed agricultural land, featuring<br />

hedges and agricultural buildings such as barns and byres, sometimes<br />

ornamented or combined with ornamental structures.<br />

4

The picturesque <strong>park</strong> (1790s–1840s)<br />

The picturesque <strong>park</strong> evolved out of aesthetic theory in the late 18th century. It was<br />

characterised by a similar framework to the 18th-century landscape <strong>park</strong>, but with a<br />

less formal arrangement of views and vistas. Famously, picturesque improvement<br />

contrasted itself to the smoothness of the landscape <strong>park</strong>’s forms. There was also a<br />

greater emphasis on access into the landscape rather than merely viewing it from<br />

key locations. W.S. Gilpin advocated picturesque improvement of regular clumps, for<br />

instance by promoting the outlines of promontories and bays through using<br />

differently toned foliage to accentuate the recesses. More formal gardens reappeared<br />

around the house with Humphry Repton leading the way.<br />

Principal features<br />

• Plantations with highly irregular outlines rather than just informally placed<br />

ovals and circles<br />

• Areas of rough woodland or topography valued as visual features<br />

• Increasing emphasis on composed scenes, but less on large-scale sweeping<br />

views<br />

• The house is framed by trees<br />

• Reintroduction of garden terraces and other formal features adjacent to the<br />

house<br />

• Use of more unusual species for individual trees.<br />

The Victorian <strong>park</strong> (1840s–1900)<br />

Private <strong>park</strong>s<br />

With the growth of plant-collecting throughout the 19th century, a far wider variety<br />

of trees was used in <strong>park</strong>s often gathered in highly prized specialist pinetums and<br />

collections set close to a mansion or detached house. Interest in the technology of<br />

horticulture saw the re-establishment of the kitchen garden as a major focal point in<br />

Victorian estates, while formal gardens flourished around the mansions. This last<br />

period of large-scale <strong>park</strong> creation came to an end with the agricultural depression<br />

of the late 19th century, while the impact of the First World War had a devastating<br />

impact on the labour-force available to country landowners.<br />

5

Fig 3 Ashridge, Hertfordshire, gardens around the house laid out to the suggestions made<br />

by Humphry Repton in the early 19th century.<br />

Principal features<br />

• Collections of exotic trees such as Wellingtonia, deodar and atlantic cedars<br />

and exotic firs and pines<br />

• Scattered exotics were also increasingly used as punctuation marks in the<br />

<strong>park</strong>land<br />

• Extensive formal garden layouts around the principal houses<br />

• Widespread avenue planting, often using trees such as Wellingtonia<br />

• Rhododendrons, coverts and other features for game cover and sport<br />

• Kitchen gardens with extensive ranges of glasshouses.<br />

Public <strong>park</strong>s<br />

From the 1830s onwards, local authorities began to address the lack of public open<br />

space in England’s growing industrial towns and cities. In terms of acreage,<br />

investment and design theory, the urban public <strong>park</strong>s of the 19th century represent<br />

as significant a phase of landscape design as the landscape <strong>park</strong>s of the 18th century.<br />

They are characterised by a cunning use of space to accommodate different uses and<br />

character areas within a constrained space. Provision for sports and games was<br />

integral from the beginning of the development of public <strong>park</strong>s. As early as 1835, J.C.<br />

6

Loudon was suggesting that ‘archery grounds, cricket grounds, bowling greens and<br />

grounds for playing golf, skittles, quoits etc may be considered useful establishments<br />

with a view to the health of citizens’. However, Loudon was a Scot, and although golf<br />

had been played on Glasgow Green since the mid-18th century, in England there was<br />

little call for it during the Victorian era.<br />

Principal features<br />

• Planted or landscaped sub-divisions to provide for different types of passive<br />

and active recreation<br />

• Formal enclosure with railings, gates and lodges<br />

• Wide range of ornamental buildings and memorials<br />

• Formal, highly ornamental flower-bedding schemes and wide range of treeplanting.<br />

Parks from 1900 onwards<br />

The last period of large-scale <strong>park</strong> creation came to an end with the agricultural<br />

depression of the late 19th century, followed by the impact of the First World War<br />

on the rural communities that serviced and maintained private estates. While the<br />

Edwardian period saw an Indian summer in garden design, no equivalent in <strong>park</strong>s has<br />

been identified.<br />

The Second World War, with its requisitions, was a further blow to sustainable<br />

<strong>park</strong>land management as were the fiscal and policy changes, affecting everything from<br />

agricultural support to death-duties, overseen by a succession of post-war<br />

Governments. By the 1950s country houses and their <strong>park</strong>s were in a state of crisis,<br />

and although there has been a renaissance in heritage sites from the 1980s onwards,<br />

there has been no significant new phase in <strong>park</strong>land design in the 20th century.<br />

Public <strong>park</strong>s continued to be popular and well-maintained features of the urban<br />

landscape for the first half of the 20th century. During this period golf – often in the<br />

form of miniature courses, putting greens or 9-hole courses – was added to many<br />

<strong>park</strong>s and seaside gardens. Reductions in local authority maintenance resources and<br />

changes in leisure activities caused the decline of public <strong>park</strong>s in the latter part of the<br />

century. More recently this has been reversed to some extent by the growing<br />

interest in and funding for the heritage aspects of public <strong>park</strong>s.<br />

7

Fig 4 A typical feature of a public <strong>park</strong>, the bandstand at Southwark Park, South London.<br />

English Heritage 2007<br />

www.english-heritage.org.uk<br />

www.helm.org.uk<br />

Available as a downloadable PDF only<br />

3 please don't print this document unless you really need to<br />

8