Types of Timber Frame.pdf - Build It

Types of Timber Frame.pdf - Build It

Types of Timber Frame.pdf - Build It

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Open Panel <strong>Timber</strong> <strong>Frame</strong> Construction<br />

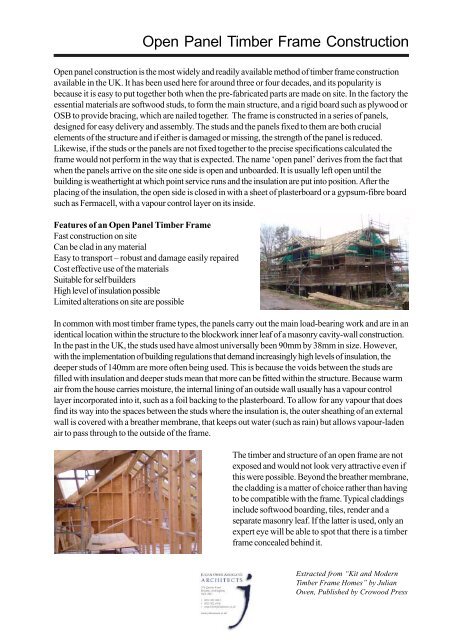

Open panel construction is the most widely and readily available method <strong>of</strong> timber frame construction<br />

available in the UK. <strong>It</strong> has been used here for around three or four decades, and its popularity is<br />

because it is easy to put together both when the pre-fabricated parts are made on site. In the factory the<br />

essential materials are s<strong>of</strong>twood studs, to form the main structure, and a rigid board such as plywood or<br />

OSB to provide bracing, which are nailed together. The frame is constructed in a series <strong>of</strong> panels,<br />

designed for easy delivery and assembly. The studs and the panels fixed to them are both crucial<br />

elements <strong>of</strong> the structure and if either is damaged or missing, the strength <strong>of</strong> the panel is reduced.<br />

Likewise, if the studs or the panels are not fixed together to the precise specifications calculated the<br />

frame would not perform in the way that is expected. The name ‘open panel’ derives from the fact that<br />

when the panels arrive on the site one side is open and unboarded. <strong>It</strong> is usually left open until the<br />

building is weathertight at which point service runs and the insulation are put into position. After the<br />

placing <strong>of</strong> the insulation, the open side is closed in with a sheet <strong>of</strong> plasterboard or a gypsum-fibre board<br />

such as Fermacell, with a vapour control layer on its inside.<br />

Features <strong>of</strong> an Open Panel <strong>Timber</strong> <strong>Frame</strong><br />

Fast construction on site<br />

Can be clad in any material<br />

Easy to transport – robust and damage easily repaired<br />

Cost effective use <strong>of</strong> the materials<br />

Suitable for self builders<br />

High level <strong>of</strong> insulation possible<br />

Limited alterations on site are possible<br />

In common with most timber frame types, the panels carry out the main load-bearing work and are in an<br />

identical location within the structure to the blockwork inner leaf <strong>of</strong> a masonry cavity-wall construction.<br />

In the past in the UK, the studs used have almost universally been 90mm by 38mm in size. However,<br />

with the implementation <strong>of</strong> building regulations that demand increasingly high levels <strong>of</strong> insulation, the<br />

deeper studs <strong>of</strong> 140mm are more <strong>of</strong>ten being used. This is because the voids between the studs are<br />

filled with insulation and deeper studs mean that more can be fitted within the structure. Because warm<br />

air from the house carries moisture, the internal lining <strong>of</strong> an outside wall usually has a vapour control<br />

layer incorporated into it, such as a foil backing to the plasterboard. To allow for any vapour that does<br />

find its way into the spaces between the studs where the insulation is, the outer sheathing <strong>of</strong> an external<br />

wall is covered with a breather membrane, that keeps out water (such as rain) but allows vapour-laden<br />

air to pass through to the outside <strong>of</strong> the frame.<br />

The timber and structure <strong>of</strong> an open frame are not<br />

exposed and would not look very attractive even if<br />

this were possible. Beyond the breather membrane,<br />

the cladding is a matter <strong>of</strong> choice rather than having<br />

to be compatible with the frame. Typical claddings<br />

include s<strong>of</strong>twood boarding, tiles, render and a<br />

separate masonry leaf. If the latter is used, only an<br />

expert eye will be able to spot that there is a timber<br />

frame concealed behind it.<br />

Extracted from “Kit and Modern<br />

<strong>Timber</strong> <strong>Frame</strong> Homes” by Julian<br />

Owen, Published by Crowood Press

Stucturally Insulated Panels (SIPs)<br />

Instead <strong>of</strong> using timber to form a frame, SIPs consist <strong>of</strong> timber-based boarding, such as oriented strand<br />

board (OSB) sandwiching sheets <strong>of</strong> a rigid foam insulation such as expanded polystyrene or<br />

polyurethane. The two materials are firmly bonded together so that they effectively act as a single<br />

structural component. The resulting panels are said to be 5 to 10- times stronger than conventional<br />

timber frame constructions. In Europe, they are used mainly for internal and external walls, although they<br />

are being used increasingly to replace rafters, because they provide a clear ro<strong>of</strong>space that can be used<br />

for bedrooms.<br />

Features <strong>of</strong> a Structural Insulated Panel (SIP) House<br />

No frame – a ‘flat pack’ house<br />

Very high levels <strong>of</strong> insulation possible with thin walls<br />

Clear ro<strong>of</strong> space for use as accommodation<br />

Low leakage <strong>of</strong> air to the outside<br />

Wide range <strong>of</strong> cladding choices<br />

Cost advantage if standard designs used<br />

Little wastage <strong>of</strong> materials on site<br />

The panels are mostly self-supporting, although occasionally timber posts may be required. A wide<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> different materials are used to make up the two components <strong>of</strong> SIPs including sheets that are<br />

not wood-based, using cement or gypsum alternatives. The vital bond between the core and the<br />

sheathing can be achieved either with adhesive or by using insulation materials that bond themselves to<br />

the board as they are created. The latter is more efficient and generally the preferred method in Europe.<br />

The thickness <strong>of</strong> the panels available varys between 70 and 250mm. The walls take the same position<br />

as an open panel frame or a block inner leaf and the full range <strong>of</strong> external cladding materials can be<br />

used, although brick is not one <strong>of</strong> the most cost-effective options.<br />

For a given thickness, insulation levels that can be achieved are high in comparison with other systems<br />

and masonry construction. In addition to this, the insulation and structure are effectively part <strong>of</strong> the same<br />

component so that the walls to SIP houses are relatively thin, freeing up more space for use in the rooms<br />

<strong>of</strong> the house – a factor that could be important on a tight site.<br />

The sheets are cut to size in the factory, with all necessary window, door and service openings formed<br />

before delivery. Lintels are only needed for wide openings, otherwise the panels are self-supporting.<br />

Services can be run either in preformed channels in the depth <strong>of</strong> the board, or in the gap between the<br />

SIP and the internal lining typically plasterboard on battens. Ro<strong>of</strong> spaces can be kept clear and the<br />

sheets will span up to about 4.8m without the need for supporting purlins.<br />

On site a crane is needed to manoeuvre the panels into place and<br />

the assembly on site is a job that is best left to specialists, who slot<br />

them together and seal the joints. The structure <strong>of</strong> an average sized<br />

house (e.g.150 sqm) can be assembled in two or three days in this<br />

way. As well as forming the entire structure <strong>of</strong> a house, the<br />

insulation level <strong>of</strong> SIPs is so good that they are sometimes used for<br />

the infill panels <strong>of</strong> oak framed houses.

Oak frame buildings are not the cheapest in comparison to the other types <strong>of</strong> frame. They are a status<br />

symbol that require a relatively generous budget. However, the cost is matched by the high quality that<br />

runs through the design, selection <strong>of</strong> materials and care taken in the manufacture and assembly. The<br />

modern oak framed house and the variations on this theme take the practices and principles <strong>of</strong><br />

carpenters from the middle ages and re-interpret them using 21 st Century factory prefabrication<br />

methods. Chunky beams, columns and rafters are used, assembled in structural bays, with slotted and<br />

dowelled joints just like the traditional frames assembled hundreds <strong>of</strong> years ago. The building is clad<br />

either by filling the gaps between the posts with insulated panels, or covering the whole structure with a<br />

cladding such as tiles, timber boards, render or brick.<br />

Features <strong>of</strong> an Oak <strong>Frame</strong> Construction<br />

Authentic traditional appearance<br />

High quality construction<br />

Structure is expressed as part <strong>of</strong> the design<br />

Weathers naturally – no need for finishes<br />

Very durable - no preservative needed in most cases<br />

Suited to ‘open plan’ design<br />

‘Green’ oak, is so called because when relatively freshly cut it is fairly easy to cut and shape. Once<br />

felled, the timber begins to harden and become impervious to water. After about 18months to two<br />

years, it has become so hard it is resistant to insects and also it is difficult to cut or sink a nail into it. As<br />

the green oak matures, it dries out and begins to shrink, twist slightly and even develop small splits. No<br />

one should acquire a green oak house unless they accept that this is part <strong>of</strong> the character <strong>of</strong> the material<br />

and a key part <strong>of</strong> its charm. The frame is made in a factory, either by hand or machine, each element<br />

designed to precisely fit with the others. A system <strong>of</strong> carpenter’s marks is used to identify how the<br />

separate parts are to be assembled and exercise that is usually carried out in the factory before the<br />

frame is dismantled and delivered to site.<br />

Once the building is weathertight, the frame<br />

usually needs to be sand-blasted or cleaned<br />

with an acid. The colour <strong>of</strong> the frame<br />

changes from cut wood to a silver grey once<br />

the frame is exposed to the weather. <strong>It</strong> then<br />

gradually darkens in colour over the years<br />

that follow. Although thanks to its hardness<br />

and strength oak needs no further treatment,<br />

it is possible to darken the external timber<br />

artificially using dye mixed with teak oil.<br />

Inside, it can be waxed, oiled or stained<br />

according to taste. Beeswax is a popular<br />

choice, turning the wood an attractive honey<br />

colour. There are also options for the way<br />

that the surface <strong>of</strong> the exposed timbers are<br />

treated.<br />

Green Oak <strong>Frame</strong> Construction<br />

Extracted from “Kit and Modern<br />

<strong>Timber</strong> <strong>Frame</strong> Homes” by Julian<br />

Owen, Published by Crowood Press<br />

Photos courtesy <strong>of</strong> Carpenter Oak<br />

and Woodland