2011 EDITION

2011 EDITION

2011 EDITION

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

2401 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA ACTGAGAACG 2401 AAACTCTTAC TTTTGT CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTG<br />

2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAGAT GCACCAGGGA 2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG CATCCTGGCC<br />

GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAG<br />

2521 AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCCTC GGGGATGCCG 2521 AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA TCTCCACTGT<br />

AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCC<br />

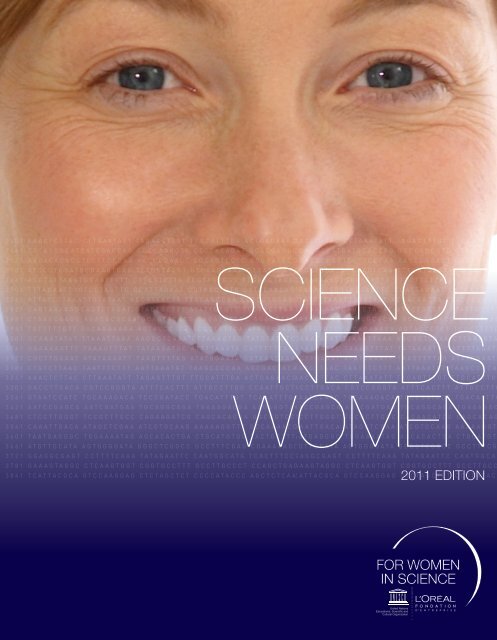

SCIENCE<br />

2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAAA GTGATCGACA 2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG ATTCCACGAA<br />

TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAA<br />

2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG TTGAAGTAGT 2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT TAGTTCCCCG<br />

CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG<br />

2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG CATACAACAG 2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CTAGAGCTGT<br />

CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG<br />

2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA CCTCGTGCAG 2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT CGAAGCAAAG<br />

ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA<br />

2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT TCCTGCTTGA 2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT TATTAGATCA<br />

GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT<br />

2881 CTAAGCAAGC AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG CAGATCACGC AGACGTTAAA 2881 CTAAGCAAGC AATTTAAAAA AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG CAGATCAC<br />

2941 TGTTTTTGTT TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTCA ATTTTGTAGT 2941<br />

NEEDS<br />

TGTTTTTGTT TAAAATTCGA TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTC<br />

3001 GCAAATATAT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTAC TATGTATGTC 3001 GCAAATATAT TTGTATTTTT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTA<br />

3061 GAAAAAATTC TAAAGTTTAT TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA CATTTTTTAA 3061 GAAAAAATTC CCTACCTTGTTAAAGTTTAT<br />

TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA<br />

3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA GATAAACAAA 3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATTTCCCT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA<br />

3181 CTGTCTTAAC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCAA AGCGACTACA 3181 CTGTCTTAAC GCTTCATGTC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCA<br />

3241 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA ACTGAGAACG 3241 AAACTCTTAC TTTTGTCGAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTG<br />

3301 GACCTTGACA CGTCCGGGTA ATTTCACTTT ATTGCCTTGG CCAATTGCTT 3301 GACCTTGACA GACATCATCC CGTCCGGGTA ATTTCACTTT ATTGCCTTG<br />

WOMEN<br />

3361 GTAATCCATC TGCAAAGACA TCCCGATACC TGACATTTGT TCAAATTTGC 3361 GTAATCCATC GAATTTCCCA TGCAAAGACA TCCCGATACC TGACATTTG<br />

3421 AATCCGAGCA AATCGATGAA TGCAGGCAGA TGAAAGACGA AAGAGGTGGC 3421 AATCCGAGCA GGAAGAGGTG AATCGATGAA TGCAGGCAGA TGAAAGAC<br />

3481 CTCCTTGGGT TCCGCTTGCC CAGAAGATCG CAGCACAGGA GGCGGTCCTG 3481 CTCCTTGGGT CCAGCTAATG TCCGCTTGCC CAGAAGATCG CAGCACAG<br />

3541 CAAATTGACA ATAGCTCGAA ATCGTGCAAG AAAAAGGTTT GCCAAAACCC 3541 CAAATTGACA TAGGCGTAAC ATAGCTCGAA ATCGTGCAAG AAAAAGGT<br />

3601 TAATGAGGGC TGGAAAATAG AGCACACTGA CTGCATGTGG TACTGCTTTA 3601 TAATGAGGGC GGCTTAGAGG TGGAAAATAG AGCACACTGA CTGCATGT<br />

3661 ATGTTGCATA AGTGGGGATA GGGCTCGGCC GCCTTTCGAG CGAAAAAGGT 3661 ATGTTGCATA GTAAGGTCTA AGTGGGGATA GGGCTCGGCC GCCTTTCG<br />

3721 GGAGGCGAGT CCTTTTCAAA TATAGAATTC CAATGGCATG TCACTTTCCT 3721 GGAGGCGAGT CGGAGAAAGT CCTTTTCAAA TATAGAATTC CAATGGCAT<br />

3781 GAAAGTAGGC CTCAAGTGGT CGGTGCCTTT GCCTTGCCCT CCAGCTGACC 3781 GAAAGTAGGC TGCTCCCTGG CTCAAGTGGT CGGTGCCTTT GCCTTGCC<br />

3841 TCATTACGCA GTCCAAGGAG CTCTAGCTCT CCCCATACCC AGCTCTCAAT 3841 TCATTACGCA GTTGTTGTGG GTCCAAGGAG CTCTAGCTCT <strong>2011</strong> <strong>EDITION</strong><br />

CCCCATAC<br />

3901 TTTTTTGTTT GTAGCCGGCT GAATTTTTTC GCCAAAGCCA GATTGAGATG 3901 TTTTTTGTTT TAAAGCACAA GTAGCCGGCT GAATTTTTTC GCCAAAGCC

P.4 - (c) Stéphane de Bourgies P. 5 - (c) UNESCO / Michel Ravassard, P. 8 - (c) Micheline Pelletier for the L’Oréal Corporate Foundation<br />

P. 9-19 - (c) V. Durruty & P. Guedj for the L’Oréal Corporate Foundation, P. 20 - (c) Christophe Guibbaud/Abacapress for the L’Oréal Corporate Foundation

SUMMARY<br />

04<br />

THE PROGRAMME<br />

08<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong> AWARD LAUREATES<br />

5 Women, 5 Outstanding Careers, 5 Major Contributions<br />

22<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong> INTERNATIONAL FELLOWSHIPS<br />

The Faces of Science for Tomorrow

4<br />

A SHARED<br />

COMMITMENT<br />

Béatrice<br />

Dautresme<br />

CEO, L’Oréal Corporate Foundation<br />

The L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science<br />

programme, through thirteen years of<br />

commitment, has given recognition to over<br />

a thousand women scientists, providing<br />

visbility and encouragement for the excellence<br />

of their work, their contribution to scientific<br />

advancement and their impact on society.<br />

Our commitment began with a contradiction:<br />

even though women excelled at all levels<br />

of upper education, they were still poorly<br />

represented at the highest levels of scientific<br />

research.<br />

Through our long-term partnership with<br />

UNESCO, we are proud to shine a spotlight<br />

each year on outstanding women who have<br />

helped change the world through science.<br />

Faced with the mounting challenges of our<br />

century, it is more important than ever that we<br />

continue to lend them our support.<br />

Each year we celebrate scientists hailing from<br />

every continent who incarnate the promise of<br />

a better world. The science they personify is<br />

modern, cross-disciplinary and open to the<br />

world: science working on behalf of humanity,<br />

ceaselessly pushing back the frontiers of<br />

knowledge, transforming and improving<br />

our lives and providing solutions to the<br />

enormous challenges that face our planet.<br />

They address such urgent issues as aging<br />

populations, global warming, the extinction<br />

of species, access to water, fighting<br />

pandemics and harnessing energy.<br />

The year <strong>2011</strong> is resolutely turned towards<br />

the sciences: the UN has proclaimed it<br />

the International Year of Chemistry and we<br />

celebrate the centennial of Marie Curie’s<br />

Nobel Prize in Chemistry, which will be<br />

sponsored in part by the L’Oréal Corporate<br />

Foundation.<br />

This year, the programme welcomes for<br />

the first time scientists from such widelyspread<br />

countries as Estonia, Iraq, Panama<br />

and Sweden. For us, this ever broader<br />

community is a source of pride and<br />

ambition, which continues to motivate our<br />

cause year after year.

Gretchen<br />

Kalonji<br />

Assistant Director-General<br />

for Natural Sciences at UNESCO<br />

This year, we are honouring women and science.<br />

<strong>2011</strong> has been proclaimed the “International year<br />

of chemistry” by the United Nations. The launch<br />

ceremonies took place at UNESCO on 27 and 28<br />

January, at which scientists and politicians talked<br />

at length about chemistry’s essential contribution<br />

to knowledge, its importance in all aspects of our<br />

everyday lives and the crucial role it will play in<br />

sustainable development.<br />

For the first time in the history of international years,<br />

a plenary session was dedicated specifically to<br />

women’s contribution to science, honouring two-time<br />

Nobel Prize winner Marie Slodowska Curie and with<br />

a presentation by Ada Yonath, winner of the Nobel<br />

Prize in Chemistry in 2009 and laureate of the<br />

L’Oréal-UNESCO Award For Women in Science in<br />

2008. Promoting the role of women in chemistry is<br />

one of the four main aims of the International year<br />

of chemistry, with a number of events taking place<br />

around the world during the year on this theme.<br />

“Madame Curie” was celebrated again at the<br />

Sorbonne on 29 January on the occasion of the<br />

100th anniversary of the Nobel Prize for chemistry.<br />

The L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science Award<br />

ceremony, held at UNESCO on 3 March, is a key part<br />

of this series of events, with five exceptional female<br />

scientists from five continents honoured for their<br />

contribution to advances in science. Two of them are<br />

eminent in the field of chemistry. And 15 fellowship<br />

winners, also from different parts of the world, will<br />

participate in the ceremony as well. Once again<br />

this year, but to a greater extent than usual,<br />

L’Oréal and UNESCO combine their efforts to<br />

spread the message summarising their mutual<br />

claim: “The world needs science and science<br />

needs women”.<br />

As the new Assistant Director-General for<br />

Natural Sciences at UNESCO and the first<br />

woman appointed to this important position, this<br />

message is particularly significant for me. With<br />

its prestigious awards and fellowships, the<br />

L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science<br />

programme achieves goals that I would like to<br />

place at the heart of what we do: working to<br />

establish true equality between men and women<br />

in research and education, promoting diversified,<br />

shared and committed science in our time<br />

to young people, and increasing cooperation<br />

with universities and greater international<br />

cooperation, not forgetting one particular<br />

dimension that the L’Oréal-UNESCO partnership<br />

has been so successful in developing: solidarity.<br />

I am thinking in particular of the steps being<br />

taken with research scientists in Africa.<br />

May the <strong>2011</strong> L’Oréal-UNESCO Awards<br />

For Women In Science be a great celebration,<br />

and together we shall make the International<br />

Year of Chemistry a success.

6<br />

DECODING<br />

OUR WORLD<br />

VISIONARY<br />

AND PROMISING<br />

RESEARCH<br />

Harnessing solar energy, clean petrol production,<br />

water depollution, understanding the interreactions<br />

between light and matter and analysing the<br />

Universe are but some of the fields of research and<br />

contributions highlighted this year.<br />

Today’s Laureates and Fellows epitomise the<br />

commitment and ambition of the L’Oréal-UNESCO<br />

For Women in Science programme. This year we<br />

honour five women in the physical sciences. Their<br />

research demonstrates to what extent the socalled<br />

“hard” sciences, far from being hermetically<br />

closed, often provide us with concrete solutions to<br />

the enormous challenges facing society today.<br />

INTERCONNECTING<br />

SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITIES<br />

In a connected and globalised world, ever bigger and<br />

stronger bridges and ties are being forged between<br />

societies. These exchanges are what make innovation<br />

and scientific research possible, and help stimulate<br />

major discoveries.<br />

The L’Oréal Corporate Foundation and UNESCO<br />

have created a community of over a thousand women<br />

scientists, fostering exchanges and creating bridges<br />

between women researchers and students in the<br />

sciences, but also between disciplines, to help make<br />

science more open and less isolated.

A LONG-TERM<br />

COMMITMENT<br />

Every year, the L’Oréal Corporate Foundation and<br />

UNESCO renew their commitment to recognising<br />

the excellence of outstanding women, encouraging<br />

scientific careers and identifying and supporting<br />

future talent.<br />

By highlighting the advances that women scientists<br />

make possible day after day, the L’Oréal-UNESCO<br />

Awards For Women in Science help create female<br />

role models, paving the way for a whole new<br />

generation of young women scientists.<br />

In 2009, two L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in<br />

Science Laureates were awarded Nobel prizes:<br />

Elizabeth Blackburn in Medecine and Ada Yonath<br />

in Chemistry. The merits of our programme are<br />

recognised in these two Nobel Awards.<br />

2401 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA<br />

2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAGAT<br />

2521 AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCCTC<br />

2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAAA<br />

2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG T<br />

2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG C<br />

2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA C<br />

Key figures:<br />

2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT T<br />

2881 CTAAGCAAGC L’OréaL-uNesCO AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG fOr CAGATCACG<br />

2941 TGTTTTTGTT TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTCA<br />

WOmeN iN sCieNCe<br />

3001 GCAAATATAT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTAC<br />

3061 GAAAAAATTC TAAAGTTTAT TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA<br />

3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA<br />

1086<br />

3181 CTGTCTTAAC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCAA<br />

3241 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA<br />

3301 GACCTTGACA CGTCCGGGTA ATTTCACTTT ATTGCCTTGG<br />

3361 GTAATCCATC TGCAAAGACA TCCCGATACC TGACATTTGT<br />

3421 AATCCGAGCA AATCGATGAA TGCAGGCAGA TGAAAGACG<br />

women scientists<br />

3481 CTCCTTGGGT TCCGCTTGCC CAGAAGATCG CAGCACAGG<br />

3541 CAAATTGACA from across ATAGCTCGAA five continents<br />

ATCGTGCAAG AAAAAGGTTT<br />

3601 TAATGAGGGC TGGAAAATAG AGCACACTGA CTGCATGTGG<br />

have been recognised<br />

3661 ATGTTGCATA AGTGGGGATA GGGCTCGGCC GCCTTTCGAG<br />

3721 GGAGGCGAGT CCTTTTCAAA by the programme<br />

TATAGAATTC CAATGGCATG<br />

3781 GAAAGTAGGC CTCAAGTGGT CGGTGCCTTT GCCTTGCCCT<br />

3841 TCATTACGCA GTCCAAGGAG CTCTAGCTCT CCCCATACCC<br />

2401 3901 AAACTCTTAC TTTTTTGTTT CTTAAATATT GTAGCCGGCT TAGAGTTTGT GAATTTTTTC TTGCATTTGA GCCAAAGCCAA<br />

2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAGAT<br />

2521<br />

in13<br />

AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA<br />

years<br />

AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCCTC<br />

2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAAA<br />

2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG T<br />

2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG C<br />

2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA C<br />

2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT T<br />

67 laureates<br />

2881 CTAAGCAAGC AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG CAGATCACGC<br />

2941 TGTTTTTGTT TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTCA<br />

1019 fellows<br />

3001 GCAAATATAT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTAC<br />

3061 GAAAAAATTC from TAAAGTTTAT 103 countries<br />

TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA C<br />

3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA G<br />

3181 CTGTCTTAAC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCAA A<br />

3241 AAACTCTTAC CTTAAATATT TAGAGTTTGT TTGCATTTGA A<br />

3301 GACCTTGACA CGTCCGGGTA ATTTCACTTT ATTGCCTTGG<br />

<strong>2011</strong><br />

3361 GTAATCCATC TGCAAAGACA TCCCGATACC TGACATTTGT<br />

3421 AATCCGAGCA AATCGATGAA TGCAGGCAGA TGAAAGACGA<br />

3481 CTCCTTGGGT TCCGCTTGCC CAGAAGATCG CAGCACAGGA<br />

In 3541 CAAATTGACA ATAGCTCGAA ATCGTGCAAG AAAAAGGTTT<br />

3601 TAATGAGGGC TGGAAAATAG 4 new AGCACACTGA countries: CTGCATGTGG<br />

3661 ATGTTGCATA AGTGGGGATA GGGCTCGGCC GCCTTTCGAG<br />

3721 GGAGGCGAGT CCTTTTCAAA Estonia<br />

TATAGAATTC CAATGGCATG<br />

3781 GAAAGTAGGC CTCAAGTGGT CGGTGCCTTT GCCTTGCCCT<br />

3841 TCATTACGCA GTCCAAGGAG CTCTAGCTCT Iraq CCCCATACCC<br />

3901 2401 TTTTTTGTTT AAACTCTTAC GTAGCCGGCT CTTAAATATT GAATTTTTTC TAGAGTTTGT GCCAAAGCCA<br />

TTGCATTTGA<br />

Panama<br />

2461 CTCAGGGCATGATGCACCAG GGCCAGGGTC CTCCACAGAT<br />

2521 AACACACGCCTCCTTCCCAA AACCCGAACT CGCAGTCCTC<br />

Sweden<br />

2581 ATCCCTGGATGCGAAGTCAG TTTGGTAAGT GTCAAGGAAA<br />

2641 ACGTATTAAGTGGAATTTTT CTTCTTCTTA TCGTAGTGGG<br />

2701 TTTAGAATTGGTCGTAGTTC CCATTAGAAT CGTAACTGTG<br />

2761 ATTATCTTAAATTGTATAAT ACCATAACTA TTACAGCGAA C<br />

2821 CAGTAAAAAGCAGTCTAGAT GTACTGCTTT ATATTGTGTT<br />

2881 CTAAGCAAGC AGACGCGCAA GCAGTTCACG CAGATCACG<br />

2941 TGTTTTTGTT TGCAGAAAGA AGTACCCTCT TCGCTTTTCA<br />

3001 GCAAATATAT TTAAATTAAA AAGGCTCAAA CTTAAAGTAC<br />

3061 GAAAAAATTC TAAAGTTTAT TATAAAATGC ATTTTAAATA<br />

3121 CGCTTGAAAT ATATAAAATT TAAGTTTTAG ATATGGAATA<br />

3181 CTGTCTTAAC TAATTTCTTT AATTAAATGT TAAGCCCCAA

8<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong><br />

LAUREATES<br />

5 Women<br />

5 Outstanding Careers<br />

5 Major Contributions<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong> LAUREATES AS SEEN<br />

bY THE PRESIDENT OF THE JURY<br />

Pr. Ahmed Zewail<br />

Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1999<br />

Through the L’Oréal-UNESCO Awards For Women in Science, the<br />

international jury strives to shed light on the infinite possibilities<br />

offered by science each year. The 15 members of the international<br />

jury were selected on their scientific merit and their commitment to<br />

women scientists.<br />

To select the Laureates, we examine their scientific achievements<br />

and the international contribution of their research, notably through<br />

their publications and peer reviews.<br />

Identifying Laureates in the emerging countries is truly challenging.<br />

In certain regions of the world, the difficulty of identifying women<br />

scientists is symptomatic of the conditions women face to access<br />

education and the sciences. This is why it is vital that we pursue our<br />

mission. Each year, L’Oréal and UNESCO renew their commitment<br />

and send out a call for nominations to over 1000 eminent scientists<br />

on every continent.<br />

In <strong>2011</strong>, we are proud to have selected a group of Laureates<br />

marked by diversity. Far from sharing the same research themes,<br />

the Laureates’ work is characterised by variety and interdisciplinarity

touching on all areas of the physical sciences, from<br />

nanoscience to the environmental sciences and cosmology. In<br />

our eyes, they represent a veritable wealth of knowledge that<br />

opens the door to infinite possibilities!<br />

Although I believe that science is currently doing rather well,<br />

I sometimes have doubts about financing mechanisms and<br />

new trends that could erode curiosity and creativity. Yet I am<br />

still optimistic about the future of science and thus the world,<br />

because it is my deep-felt conviction that human beings can<br />

adapt to anything.<br />

An international award like L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women<br />

in Science helps increase awareness of the role women<br />

scientists play in finding solutions for planetary issues. It<br />

seems the best way to reach absolute gender parity in<br />

scientific research is to perpetuate successful role models<br />

through innumerable awards and scholarships, and to give life<br />

to an influential community.<br />

PR. FAIZA<br />

AL-KHARAFI<br />

Laureate for Africa<br />

and the Arab States<br />

PR. SILVIA<br />

TORRES-PEIMBERT<br />

Laureate for Latin America<br />

PR. JILLIAN<br />

BANFIELD<br />

Laureate for North America<br />

PR. VIVIAN<br />

WINg-WAH YAM<br />

Laureate for Asia<br />

and the Pacific<br />

PR. ANNE<br />

L’HUILLIER<br />

Laureate for Europe

10<br />

PR. FAIZA<br />

AL-KHARAFI<br />

Kuwait University, Safat, KUWAIT<br />

Laureate for Africa and the Arab States<br />

Fight Corrosion<br />

Corrosion is a natural process: metals react to oxygen in the<br />

air and are paradoxically vulnerable to their environment.<br />

Less well known, corrosion also affects all machinery made<br />

from iron or steel. The cost of corrosion is estimated at about<br />

2% of world gDP. Every second, roughly 5 tonnes of steel are<br />

transformed into rust! This explains why corrosion is such a<br />

big concern for mining, agriculture and heavy industry.<br />

Professor Faiza Al-Kharafi has spent her career investigating<br />

the mechanisms underlying the corrosion of metals and<br />

finding practical solutions to inhibit the process. Her work has<br />

had a major impact on the development of the energy sector<br />

in Kuwait as well as on improving water treatment.<br />

Founder of the first Corrosion and Electrochemistry Research<br />

Laboratory at Kuwait University in 1967, she has devoted her<br />

research to the study of copper and platinum, two metals<br />

widely used in many important industrial processes.<br />

Responding to an<br />

Environmental Issue<br />

Corrosion, the most common example of which is rust,<br />

is the permanent and generally undesirable change in<br />

metal when it reacts with its environment. But sometimes<br />

a metal can actually speed up a chemical reaction and<br />

remain unchanged itself. This is called catalysis, and it<br />

is extremely important in many industrial applications.<br />

Platinum, for example, interacts with numerous<br />

molecules making it an extremely valuable catalyst.<br />

A specialist in platinum, Faiza Al-Kharafi naturally zeroed<br />

in on this property, especially since platinum catalysts are<br />

widely used in oil refining to increase the octane rating of<br />

gasoline, such as the SP 95 and SP 98 fuels commonly<br />

found in service stations. Yet metal catalysts like platinum<br />

also generate side reactions that can produce harmful<br />

components such as benzene, which is carcinogenic.<br />

Faiza Al-Kharafi and her team discovered a new class<br />

of catalysts based on the element molybdenum, which<br />

does not have the secondary reactions of platinum and<br />

can be used to increase the octane number of gasoline

For her work on corrosion,<br />

a problem of fundamental importance<br />

to water treatment and<br />

the oil industry<br />

without producing benzene. This was a veritable revolution for<br />

the refining industry, reducing costs and making it safer for<br />

refinery workers, the environment and the general public. It<br />

was also a major advance for water treatment, since this new<br />

class of catalyst can also be used to extract certain pollutants<br />

from drinking water.<br />

A Career in Chemistry<br />

After earning a BSc degree from Ain Shams University in<br />

Egypt, Faiza Al-Kharafi received her MSc and PhD from<br />

Kuwait University, where she joined the faculty in 1967.<br />

From 1993 to 2002 she served as head of the Chemistry<br />

Department, Dean of the Faculty of Science and President<br />

of the University, becoming the first woman to head a major<br />

university in the Arab world. In 2002, she left her university<br />

post to serve on the Kuwaiti government’s Supreme Council<br />

of Planning and Development.<br />

Professor Al-Kharafi has greatly contributed to the promotion<br />

of science in Kuwait. She has been the research director for<br />

over twenty research projects in corrosion and has facilitated<br />

fruitful international collaborations between Kuwait University<br />

and other universities in France and around the world. She is<br />

a member of the United Nations University Council and Vice<br />

President of The Academy of Sciences for the Developing<br />

World.<br />

FAIZA<br />

AL-KHARAFI<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

EXEMPLARY DEDICATION<br />

Faiza Al-Kharafi has been committed<br />

to science since a young age.<br />

She went on to become a leading<br />

scientific figure in Kuwait, experiencing<br />

first-hand women’s contribution<br />

to the development of science<br />

and their strong commitment. As<br />

president of Kuwait University from<br />

1993 to 2002, she was in charge<br />

of 1,500 staff members, more than<br />

5000 employees and more than<br />

20,000 students annually. Today,<br />

she emphasises the important role<br />

women play in scientific research.<br />

“In the Faculty of Science at Kuwait<br />

University, more than 40 percent<br />

of the staff members and students<br />

are female. Their contribution to the<br />

development of science in general<br />

is very important.”<br />

A WOMAN WHO ACCEPTS<br />

CHALLENgES<br />

Throughout her career, Faiza<br />

Al-Kharafi has noted how “many<br />

people underestimated the abilities<br />

of women in science,” she explains.<br />

“Another big challenge was finding<br />

the right balance between my work<br />

and raising my children. By hard<br />

work, dedication and commitment,<br />

and also thanks to time management<br />

and family help,” she says,<br />

she was able to succeed at this<br />

difficult juggling act.<br />

Professor Al-Kharafi is extremely<br />

pleased to receive this award that<br />

promotes the cause of women<br />

scientists. “I very much hope that<br />

this prize will encourage young<br />

people – especially girls – to<br />

specialise in scientific fields and be<br />

more involved and committed to<br />

the development of society.”

12<br />

PR. SILVIA<br />

TORRES-<br />

PEIMBERT<br />

University of Mexico (UNAM), Mexico City, MExICO<br />

Laureate for Latin America<br />

Nebulae: Birthplaces and<br />

Graveyards of Stars<br />

There are more stars in the Universe than grains of sand on<br />

Earth, and our galaxy alone has more than 200 billion stars!<br />

These staggering figures explain the interest and difficulties in<br />

studying these distant suns.<br />

Like humans, stars are not eternal: they are born, grow old<br />

and die. The major events in the life cycle of a star take place<br />

in the nebulae, the regions of the universe with a high density<br />

of hydrogen and helium gas, dust, and other gases. Specific<br />

nebulae called HII regions serve as birthplaces for new stars,<br />

while planetary nebulae are produced by the death of stars,<br />

which explode or run out of fuel.<br />

Professor Torres-Peimbert has devoted her career to<br />

decoding nebulae, and her work provides scientists with<br />

valuable insights into the origins of stars and the evolution of<br />

the universe.<br />

Starlight: a Look Back in Time<br />

The chemical composition of a nebula, which can be<br />

determined by analyzing its light spectrum, contains<br />

the history of the nuclear transformations that have<br />

occurred within a star, and can be used to understand<br />

the events of its life cycle.<br />

Very early on, Professor Torres-Peimbert took an<br />

interest in the Orion Nebula, which contains hundreds<br />

of stars at various stages of development. In 1977,<br />

she published the first complete analysis of the<br />

composition of this nebula, which showed that it is<br />

chemically very similar to our own Sun.<br />

By observing the planetary nebulae from numerous<br />

galaxies, she has helped understand the beginning of<br />

the universe when the first stars were born nearly 14<br />

billion years ago. She also provided new insight into<br />

the stellar aging process.

For her work on the chemical<br />

composition of nebulae which is<br />

fundamental to our understanding<br />

of the origin of the universe<br />

The Future of the Universe<br />

In the first three minutes following the Big Bang, the only<br />

elements produced in abundance were hydrogen and helium.<br />

The other elements were created later via fusion processes<br />

inside stars. The respective quantity of helium and hydrogen in<br />

the early universe is extremely important because it can help<br />

shape our understanding of the first moments of the universe.<br />

By studying the Large Magellanic Cloud, the brightest HII<br />

region visible from Earth, and the Orion Nebula, Professor<br />

Torres-Peimbert and her colleagues were the first to establish<br />

differences in helium abundance among nebulae from different<br />

galaxies. According to their research, the amount of helium<br />

in the universe has increased throughout its evolution, which<br />

could shed new light on the future of the universe.<br />

At this early stage of the 21st century, Silvia Torres-Peimbert is<br />

at the leading edge of research on the very first generations of<br />

stars and galaxies, which remain one of the major mysteries of<br />

astronomical research.<br />

Sharing Stars<br />

with the Whole World<br />

Professor Torres-Peimbert received her bachelor’s degree at<br />

the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and<br />

her PhD in Astronomy at the University of California - Berkeley.<br />

She has been a professor in the Faculty of Sciences at UNAM<br />

since 1972 and a professor in the Institute of Astronomy since<br />

1976.<br />

She has received several awards from the Mexican Physical<br />

Society, the National University of Mexico, and other national<br />

and international organizations including the guillaume Budé<br />

Medal from the Collège de France. She is a member of the<br />

American Astronomical Society, the Astronomical Society<br />

of the Pacific, TWAS, The Academy of Sciences for the<br />

Developing World and Vice President of the International<br />

Astronomical Union.<br />

She has been chief editor of a scientific journal and has<br />

delivered more than 250 talks for the general public. She also<br />

produces TV and radio shows designed to popularise science.<br />

SILVIA TORRES-<br />

PEIMBERT<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

PASSION BEATS TRADITION<br />

“When I was a student,” she pointed<br />

out, “women in Mexico were not<br />

expected to have a career”. Although<br />

her family was supportive throughout<br />

her studies, she still remembers the<br />

feeling of being at cross purposes with<br />

the principles of traditional education.<br />

That is why she also insists on the<br />

need to promote “deeper changes<br />

in the attitudes of men and women<br />

starting early in life.”<br />

TEACHINg NEW ATTITUDES<br />

TO OUR CHILDREN<br />

“The main challenges I had to overcome<br />

were my own expectations of<br />

the role of women in society. At several<br />

stages in my life, I had to stop and<br />

reflect on my real interests, in order to<br />

prioritize my activities,” she explains,<br />

adding that when she looks back on<br />

her choices, she is “very glad to have<br />

been so defensive of my career.”<br />

For future generations, she emphasizes<br />

the need to instil new attitudes as early<br />

as possible: “Significant differences in<br />

attitudes are taught to boys and girls<br />

at an early age, and are very difficult to<br />

discard later in life.”<br />

ACCOMPLISHINg MORE<br />

AND BETTER WITH LESS<br />

Scientists in the developing countries<br />

must deal with additional hardships,<br />

such as “carrying out competitive<br />

research with fewer resources and<br />

outdated equipment.” With fewer<br />

scientists per capita and only a small<br />

share of GDP invested in science, the<br />

developing countries have a real need<br />

for scientists.

14<br />

PR. JILLIAN<br />

BANFIELD<br />

University of California, Berkeley, USA<br />

Laureate for North America<br />

Between Life and Matter<br />

Among the indispensable elements for the creation of living<br />

matter are air, water, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, iron,<br />

copper and zinc. Yet one thing is missing: without the help<br />

of microorganisms, these elements cannot be assimilated by<br />

more complex living organisms. Microorganisms transform<br />

phosphorus into phosphate, sulphur into sulphate, etc.<br />

Consequently, life can arise where living bacteria encounter<br />

bits of matter. Even more surprising, we now know that the<br />

biological disintegration of rocks in the outer layer of the Earth<br />

is essential for maintaining life on our planet.<br />

Professor Jillian Banfield has specialised in the association of<br />

minerals and microscopic forms of life, two areas of science<br />

that at first glance appear to have little in common. From her<br />

unique vantage point at the interface of these fields, she has<br />

revealed rich secrets about their fundamental interactions. She<br />

has even proven that microorganisms have the capacity to<br />

influence large-scale geological processes like erosion, and to<br />

construct unique materials from molecular building blocks.<br />

Bordering between the physical and biological worlds,<br />

these microorganisms can no longer be dissociated from<br />

their natural environments.<br />

What if Evidence of Life<br />

Was Recorded in Minerals?<br />

This would help answer a key question in space<br />

exploration: now that we have found water, could there<br />

be life on Mars? Astrobiology, also called exobiology, the<br />

study of life in the universe, is another one of Professor<br />

Banfield’s projects. She has demonstrated how the kinds<br />

of biological processes necessary for life can result in the<br />

production of unique crystalline materials that provide a<br />

“signature” for life, serving as evidence that<br />

microorganisms once inhabited a particular environment.

For her work on bacterial and<br />

material behaviour under<br />

extreme conditions relevant to<br />

the environment and the Earth<br />

Life Survives even under<br />

the Harshest Conditions<br />

By studying the interactions of microorganisms in extreme<br />

environments such as ore deposits, Jillian Banfield has shown<br />

how they have adapted to hostile conditions. She elucidated<br />

the mechanisms by which these organisms produce energy<br />

and obtain essential nutrients from metal sulphide ore.<br />

She also revealed how certain bacteria contribute to the<br />

acidification process that occurs in these mines, producing<br />

toxic wastewater that can pollute groundwater, which was<br />

previously attributed to a spontaneous chemical reaction.<br />

Once again, the physical and biological components of the<br />

terrestrial ecosystem are not isolated from each other.<br />

Professor Banfield and her students have sequenced the<br />

genomes of the different species within this community and<br />

catalogued the proteins they produce, fully characterizing this<br />

unique microbial ecosystem. Their work has improved our<br />

understanding of how life survives in even the most unlikely<br />

places.<br />

A Career Devoted<br />

to Bio-Geo-Chemistry<br />

Jillian Banfield received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in<br />

geology from the Australian National University. She completed a<br />

PhD in Earth and Planetary Science at Johns Hopkins University<br />

in 1990. From 1990-2001 she was a professor in the geology<br />

and geophysics Department and in the Materials Science<br />

Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since then she<br />

has been a professor in the Materials Science Department and<br />

the Earth and Planetary Science Department at the University<br />

of California-Berkeley and an affiliate scientist at the Lawrence<br />

Berkeley National Laboratory.<br />

Professor Banfield has been honoured with numerous<br />

prestigious awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship (1999-<br />

2004), the Dana Medal of the Mineralogical Society of America<br />

(2010), and a John Simon guggenheim Foundation Fellowship<br />

(2000). She was elected to the U.S. National Academy of<br />

Sciences in 2006.<br />

JILLIAN<br />

BANFIELD<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

INTERCONNECTIVITY<br />

AS A SOURCE OF HOPE<br />

If she were allowed just one word<br />

to describe what she hopes to<br />

contribute to the world of research,<br />

Jillian Banfield would choose<br />

“interconnectivity” – perhaps her way<br />

of saying that nothing happens in a<br />

vacuum. In a world where actions<br />

and reactions are interrelated, her<br />

research underscores how each<br />

phenomenon influences and is<br />

influenced by others and thus the<br />

importance of interconnectivity.<br />

“I have a lot of hope that science<br />

can provide answers, such as new<br />

sustainable technologies, innovative<br />

medical treatments, strategies for<br />

carbon sequestration, etc.”<br />

URgENT NEED FOR<br />

SUSTAINABLE LIFESTYLES<br />

From her interdisciplinary<br />

perspective, Professor Banfield<br />

places a premium on sustainability.<br />

“We are changing the biosphere in a<br />

complex manner with unpredictable<br />

results. Finding ways to live<br />

sustainably within our environment,<br />

without destroying it, seems to me to<br />

be the most urgent challenge facing<br />

our planet today.”<br />

THE VALUE OF WOMEN’S<br />

PERSPECTIVE IN SCIENCE<br />

Professor Banfield welcomes the<br />

movement in recent decades to<br />

facilitate the access to scientific<br />

careers for women. She also<br />

recognises the value of women’s<br />

perspective in science: “It seems<br />

clear to me from personal experience<br />

that women approach problems<br />

differently from men. I suspect that<br />

women tend to see things more<br />

holistically and be less forceful in the<br />

ways in which they offer opinions.”

16<br />

PR. VIVIAN<br />

WING-WAH<br />

YAM<br />

Hong Kong University, CHINA<br />

Laureate for Asia and the Pacific<br />

The Sun: a Free, Unlimited Source<br />

of Energy that is Largely Wasted<br />

There are several renewable and sustainable energy solutions<br />

like solar power, which could provide an unlimited source of<br />

energy. Yet a few obstacles must still be resolved, such as<br />

the low efficiency of solar cells and their high supply costs.<br />

Currently, efficiency is low because these solar cells capture<br />

only some parts of light. The most efficient solar cells today<br />

are made from silicon crystals, are very expensive to produce<br />

and are able to convert around 30 percent of the solar energy<br />

they absorb. Clearly, this is a vital challenge for the future of<br />

our technological and industrial societies and thus for humanity<br />

as a whole.<br />

In Search of the Holy Grail:<br />

New Materials<br />

By developing and testing new and photoactive materials,<br />

Professor Yam and her colleagues hope to overcome these<br />

limits. We can now envision innovative photoactive materials<br />

based on organometallics with new properties by combining<br />

components associating metal atoms and organic<br />

molecules that absorb or emit light in an optimum<br />

manner. Professor Yam has focused her attention on<br />

this class of versatile photoactive materials. Depending<br />

on the type of metal at the core of the complex and the<br />

nature of the surrounding organic molecule, photoactive<br />

materials can absorb and emit light at a range of different<br />

wavelengths and efficiencies. Her research has led to the<br />

discovery of several materials with unique light absorption<br />

properties that may prove useful for harnessing solar<br />

energy.<br />

We can imagine imitating a well-known natural photochemical<br />

process, the photosynthesis of plants, which<br />

has been transforming sunlight into energy on Earth for<br />

billions of years.<br />

Professor Vivian Yam has spent years investigating<br />

methods to develop photoactive materials capable of<br />

absorbing light energy in their chemical bonds and then<br />

to convert it into electrical energy.

For her work on light-emitting<br />

materials and innovative ways<br />

of capturing solar energy<br />

In recent years, chemists have also focused their research<br />

on physio-chemical transformations triggered by light to<br />

better understand this phenomenon and to take advantage<br />

of light-molecule interactions. The idea is to design electronic<br />

“communication” pathways by constructing nanometric<br />

complexes using organic molecules, which when brought into<br />

the presence of metal atoms, assemble themselves into organometallic<br />

molecular structures.<br />

In molecular electronics, Professor Yam has also tested the<br />

capacity of organic and organometallic systems to transfer or<br />

process information. Her work shows that these molecules<br />

can serve as molecular junctions because they act like electric<br />

wires.<br />

From Oil Spills to Medicine<br />

The photoactive materials developed by Professor Yam have<br />

far more applications than just solar energy. Many technologies<br />

we use daily rely on photoactive materials, such as<br />

organic light-emitting diode displays (OLED). The discovery<br />

and development of materials for efficient white organic lightemitting<br />

diodes (WOLEDs) will also have a huge impact to<br />

meet the challenge towards the launching of a more efficient<br />

solid-state lighting system as lighting currently takes up about<br />

19 % of the global power. Yet, biology is probably one of its<br />

most spectacular fields of application. By emitting light when<br />

exposed to oil or heavy metal ions, for example, these materials<br />

could be used to detect environmental hazards such as<br />

an oil spill or radioactive contamination. In healthcare, photoactive<br />

materials could also serve as chemosensors, detecting<br />

glucose in the blood of diabetics or the presence of malignant<br />

cells.<br />

The Youngest Member of the<br />

Chinese Academy of Sciences<br />

Professor Yam received her bachelor’s and PhD degrees from<br />

the University of Hong Kong. She taught at City Polytechnic<br />

of Hong Kong before joining the University of Hong Kong as<br />

a faculty member. She has served as the Chair Professor of<br />

Chemistry since 1999 and headed the chemistry department<br />

for the two terms from 2000 to 2005.<br />

At age 38, she was the youngest member ever elected to the<br />

Chinese Academy of Sciences. She is also a Fellow of TWAS,<br />

the Academy of Sciences for the Developing World, and<br />

was awarded the State Natural Science Award and the RSC<br />

Centenary Medal.<br />

VIVIAN WINg-<br />

WAH YAM<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

NO gENDER DIFFERENCE<br />

IN SCIENCE<br />

“I do not think there is a difference between<br />

men and women in terms of their intellectual<br />

ability and research capabilities. As<br />

long as one has the passion, dedication<br />

and determination to pursue research<br />

wholeheartedly, one can excel regardless<br />

of one’s gender or background.”<br />

She concedes, however, that women<br />

may still feel discouraged about pursuing<br />

science. “Many young women are still<br />

worried about the barriers they might face<br />

in their careers posed by possible gender<br />

stigmas. This is particularly prevalent in<br />

Asian countries, and even in major modernised<br />

cities like Hong Kong, albeit globalised,<br />

where conventional or even biased<br />

Chinese values still prevail.”<br />

CHEMISTS ARE ARTISTS<br />

Professor Vivian Wing-Wah Yam describes<br />

the boundless possibilities of chemistry and<br />

the beauty of this discipline. “One of the<br />

beauties of chemistry is the ability to create<br />

new molecules and chemical species. I<br />

have always associated chemists with<br />

artists, creating new things with innovative<br />

ideas,” affirms Professor Yam. She<br />

also points out the interdisciplinarity of<br />

research which can lie at the crossroads<br />

of chemistry, physics and engineering<br />

to respond to energy and environmental<br />

challenges, or at the junction of chemistry<br />

and medicine for the development of new<br />

biomedical applications.<br />

ENERgY, THE CHALLENgE<br />

OF THE CENTURY<br />

Alternative sources of clean, renewable<br />

energy, are a top priority because they<br />

are linked to several other key issues like<br />

water scarcity, global warming and climate<br />

change. “There are many challenges facing<br />

our planet today, including food and healthcare.<br />

However, I believe energy is the most<br />

urgent challenge because once it is solved,<br />

it will have a positive impact on the others,<br />

since they are all interconnected in one way<br />

or another. Everything is linked to our everincreasing<br />

demand for energy!”

18<br />

PR. ANNE<br />

L’HUILLIER<br />

Lund University, SWEDEN<br />

Laureate for Europe<br />

The Fastest Cameras ever made<br />

To capture the movement of an electron in an atom, you<br />

need a “camera” with a shutter speed of a billionth of a<br />

billionth of a second. We have now entered the timescale<br />

of the attosecond, which is to the second what the second<br />

is to the age of the universe, estimated at about 13.7 billion<br />

years.<br />

For a long time, most of the extremely fast molecular events<br />

that form the basis of important natural phenomena like<br />

photosynthesis or of technological devices like microchips<br />

were invisible to experimental science, simply because we<br />

did not have the ability to capture events on such short<br />

timescales. Thanks to the research of Professor Anne<br />

L’Huillier and other scientists, we have developed the tools<br />

to study the ultrafast processes that form the foundation<br />

for most of our observations of the natural world.<br />

The Key to Ultrafast Pulses<br />

generating ultrafast light pulses is no easy task. The<br />

laws of physics dictate that an extremely short pulse of<br />

light will be a mixture of many different wavelengths; in<br />

physics parlance, it has a large bandwidth. For years,<br />

the problem of obtaining such a large bandwidth<br />

represented a major roadblock to ultrafast science.<br />

At the end of the 1980s, however, Anne L’Huillier, then<br />

a young researcher at the Centre d’Etudes de Saclay<br />

in France, stumbled onto the solution to this problem.<br />

By focusing an intense pulse of laser light into a gas,<br />

high-order harmonics of the laser light – similar to the<br />

harmonics of a musical instrument – were generated<br />

and light of the appropriate bandwidth was obtained.<br />

Since the mid-1990s, Anne L’Huillier and her<br />

colleagues have continued to study these processes<br />

from a theoretical and experimental perspective in<br />

Lund, Sweden.

For her work on the development<br />

of the fastest camera for recording<br />

the movement of electrons in attoseconds<br />

(a billionth of a billionth of a second) DARE TO DO RESEARCH<br />

The Potential of the Attosecond<br />

Attosecond physics has emerged as one of the most<br />

promising areas in atomic and molecular science.<br />

Technologies based on attosecond pulses could allow us to<br />

observe the movement of electrons in atoms and molecules<br />

in real-time, enhancing our understanding of the structure of<br />

matter and its interaction with light.<br />

A Career Evolving<br />

at the Speed of Light<br />

Anne L’Huillier was born in Paris and pursued her<br />

undergraduate studies at the Ecole Normale Supérieure,<br />

majoring in mathematics and physics. She received her PhD<br />

in Physics at the University of Paris VI in 1986, performing<br />

her research at the French Atomic Energy Commission and<br />

Centre d’Etudes de Saclay. She completed her postdoctoral<br />

work in Sweden and the United States. She was a researcher<br />

for the Service des Photons, Atomes and Molécules (SPAM),<br />

Centre d’Etudes de Saclay from 1986 to 1995.<br />

In 1995, Anne L’Huillier moved to Sweden to be a lecturer in<br />

the physics department of Lund University and was named<br />

professor in 1997. She has been honoured with early-career<br />

awards from the French Physics Society and the Royal<br />

Swedish Academy of Sciences, and more recently, the Julius<br />

Springer Prize for Applied Physics (together with Professor<br />

Ferenc Krausz).<br />

She has been a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of<br />

Sciences since 2004 and was awarded an ERC Advanced<br />

Research grant from the European Research Council in 2008.<br />

ANNE<br />

L’HUILLIER<br />

IN HER OWN<br />

WORDS<br />

“To be a researcher and a professor<br />

is a fantastic profession,” says Anne<br />

L’Huillier, but adds, “I’m quite sure<br />

there are many women who can do it<br />

but maybe don’t dare”. As she sees<br />

it, many are discouraged by the way<br />

research is organised and the structure<br />

of the university system in many<br />

countries. She also believes “the<br />

heart of the problem comes much<br />

earlier, at school and in families.<br />

Young girls need to understand they<br />

can also do science if they want to.<br />

Their families and teachers – society<br />

as a whole – all need to convey this<br />

message.”<br />

She also adds that in terms of<br />

leadership, women might have a<br />

different approach that can make a<br />

difference. “Generally speaking, a<br />

group works so much better when<br />

there is gender balance. This is true<br />

at a group level and at the level of a<br />

scientific community.”<br />

SCIENCE MEANS RIgOROUS<br />

SELF-DISCIPLINE BUT ALSO<br />

BEINg OPEN WITH OTHERS<br />

In her approach to research,<br />

Professor L’Huillier considers<br />

that how one does science is as<br />

important as what one investigates.<br />

When pressed to choose just one<br />

word to describe what she hopes her<br />

scientific contribution will represent,<br />

she hesitates before answering:<br />

“‘Rigorous’ is the word I can come<br />

up with. Combining experimentation<br />

and theory, and trying to go as<br />

deeply as possible is the way I like to<br />

think about what I’m doing. Sharing<br />

and discussing ideas with other<br />

people, colleagues and students is<br />

also very important for research to be<br />

successful.”<br />

A SENSE OF SHARINg<br />

AND LISTENINg<br />

When Professor L’Huillier arrived in<br />

Sweden in 1995 she discovered her<br />

passion for teaching, which has not<br />

abated for the past 15 years:<br />

“I found that teaching brought me<br />

something I had been missing from<br />

my profession as a researcher,<br />

something more concrete and useful!<br />

I hope my way of teaching will have<br />

an impact on my students and<br />

influence the way they learn science.”

20<br />

INTERNATIONAL<br />

JURY <strong>2011</strong><br />

L’ORÉAL-UNESCO AWARDS, PhySiCAL SCiENCES<br />

(PhySiCS AND ChEMiSTRy)<br />

From left to right, 1 st row : Pr. J. King, Pr. M. Brimble, Pr. B. Barbuy, Pr. J. Ragai<br />

2 nd row : Pr. C. de Duve, Pr. A. Robledo, Pr. W. Winnick, Pr. S. Canuto, Pr. G. Ogunmola, Pr. A. Zewail<br />

3 rd row : Dr. L. Gilbert, Pr. H.E. Stanley, Pr. M. Maaza, Pr. M. Chergui, Pr. C. Amatore, Pr. C-L. Bai.

President of the Jury<br />

Professor Ahmed ZeWAiL<br />

Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1999<br />

California Institute of Technology, CA, USA<br />

founding President<br />

Professor Christian de duVe<br />

Nobel Prize in Medicine, 1974<br />

Institut de Pathologie Cellulaire, BELGIUM<br />

honorAry President<br />

irina BoKoVA<br />

Director-General, UNESCO<br />

AfriCA And ArAB stAtes<br />

Professor Jehane rAgAi<br />

Department of Chemistry, School of Sciences and Engineering,<br />

The American University in Cairo (AUC), EGYPT<br />

Professor gabriel ogunMoLA (for l’UNESCO)<br />

Chairman, Board of Trustees, and Chancellor, Lead City University, Ibadan,<br />

Chairman, Institute of Genetic Chemistry & Laboratory of Medicine, Ibadan, NIGERIA<br />

Professor Malik MAAZA<br />

iThemba LABS-National Research Foundation of South Africa, Somerset West,<br />

Western Cape Province, SOUTH AFRICA<br />

AsiA - PACifiC<br />

Professor Chun-Li BAi<br />

Executive Vice President and President of the Graduate University,<br />

Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, CHINA<br />

Professor Margaret BriMBLe (Laureate 2007)<br />

Chair of Organic and Medicinal Chemistry, University of Auckland, Auckland, NEW ZEALAND<br />

euroPe<br />

Professor Christian AMAtore<br />

Département de Chimie, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, FRANCE<br />

Professor Majed Chergui<br />

Professor of Physics and Chemistry, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology<br />

Honorary Professor, University of Lausanne, SWITZERLAND<br />

Professor Julia King<br />

Vice Chancellor, Aston University, Birmingham, UNITED KINGDOM<br />

doctor Laurent giLBert (for L’OREAL)<br />

Director, International Development of Advanced Research, L’Oréal FRANCE<br />

LAtin AMeriCA<br />

Professor Beatriz BArBuy (Laureate 2009)<br />

Professor, Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics and Atmospheric Sciences University<br />

of São Paulo, BRAZIL<br />

Professor sylvio CAnuto<br />

Institute of Physics, University of São Paulo, Brazil, BRAZIL<br />

Professor A. roBLedo<br />

Senior Research Scientist, Physics Institute, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM),<br />

Mexico City, MEXICO<br />

north AMeriCA<br />

Professor Mitchell WinniK<br />

University Professor, Chemistry Department, Faculty of Arts and Science University of Toronto,<br />

CANADA<br />

Professor h. eugene stAnLey<br />

University Professor, Professor of Physics; Professor of Physiology,<br />

and Director, Center for Polymer Studies, Boston University, USA<br />

2 PAST LAUREATES JOIN<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong> PHYSICAL SCIENCES JURY<br />

Beatriz<br />

Barbuy<br />

Member of the Jury and 2009 Laureate<br />

“ After winning the L’Oréal-UNESCO Award<br />

For Women in Science, I had the incredible<br />

chance to share my research with the general<br />

public. By highlighting the contributions<br />

of each laureate, For Women in Science<br />

undoubtedly creates leverage for women<br />

researchers.<br />

As a result, it is now a true source of<br />

motivation in the ongoing quest for<br />

excellence which shows that with<br />

perseverance and tenacity,<br />

we can overcome any obstacle. ”<br />

Margaret<br />

Brimble<br />

Member of the Jury and 2007 Laureate<br />

“ One of the numerous challenges facing<br />

women scientists is to strike the right balance<br />

to successfully handle a multi-faceted career.<br />

Women researchers are generally asked to<br />

teach and serve as mentors in addition to their<br />

high-level research.<br />

The importance of an award like<br />

L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science<br />

is to highlight outstanding women who can<br />

become veritable role models for future<br />

generations. After receiving my For Women in<br />

Science award, I was named president of the<br />

Rutherford Foundation of the Royal Society of<br />

New Zealand, which aims to support young<br />

researchers as they start their careers. ”

22<br />

THE <strong>2011</strong><br />

INTERNATIONAL FELLOWS:<br />

THE FACES OF SCIENCE<br />

FOR TOMORROW<br />

An International Network<br />

• Each year, 15 young women are encouraged through an<br />

International Fellowship to pursue their research abroad.<br />

• Along with the International Fellowships, national<br />

fellowships help women doctoral students to pursue<br />

research in their home country.<br />

• In total every year, more than 200 young women<br />

scientists are supported by the L’Oréal-UNESCO<br />

For Women in Science Fellowship programmes.<br />

Year after year, an international network continues<br />

to develop, reinforcing the potential for exchanges<br />

and knowledge sharing.<br />

L’ORÉAL-UNESCO SPECiAL FELLOWShiP<br />

“iN ThE FOOTSTEPS OF MARiE CURiE”<br />

Marcia Roye, PhD in Molecular Virology<br />

Lecturer in Biotechnology, Research Faculty of<br />

Pure and Applied Sciences, Associate Dean of<br />

graduate Studies, University of the West Indies,<br />

Kingston, Jamaica<br />

The celebration of the Marie Curie Nobel Prize Centennial<br />

is a real opportunity for the L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women<br />

Isabel Cristina<br />

Chinchilla soto<br />

COsTa riCa<br />

Alejandra<br />

Jaramillo gutierrez<br />

PaNama<br />

Andia<br />

Chaves fonnegra<br />

COLOmBia<br />

in Science programme to reaffirm its commitment to women<br />

scientists throughout their careers through the creation of a<br />

“Special Fellowship”.<br />

This new fellowship will be awarded to a former recipient of a<br />

For Women in Science International Fellowship who, through her<br />

outstanding career over the past ten years, incarnates the future<br />

of science.<br />

The first “Special Fellowship” is awarded to the Marcia Roye<br />

of Jamaica, who received a UNESCO-L’Oréal International

Samia elfékih<br />

TuNisia<br />

Hagar gelbard-sagiv<br />

israeL<br />

Fellowship in 2000 for her research on geminivirus, an insectborne<br />

virus that devastates crops around the world.<br />

Dr. Marcia Roye is passionate about research that has a direct<br />

impact on the lives of people. Her enthusiasm has been the<br />

driving force behind a particularly rich scientific career, and by<br />

age 42, she has already transformed the daily lives of numerous<br />

inhabitants of her native Jamaica and elsewhere.<br />

Her research in molecular virology focuses on two major projects.<br />

The first aims to improve the situation of Jamaican farmers who<br />

Germaine L.minoungou<br />

BurKiNa fasO<br />

Triin Vahisalu<br />

esTONia<br />

Mais absi<br />

syria<br />

Justine germo Nzweundji<br />

CamerOON<br />

Ladan Teimoori-Toolabi<br />

iraN<br />

Reyam al-malikey<br />

iraQ<br />

Fadzai Zengeya<br />

ZimBaBWe<br />

Nilufar mamadalieva<br />

uZBeKisTaN<br />

grow cash crops like peas and tomatoes, and the second is<br />

designed to help HIV patients.<br />

These two seemingly distinct fields of research have two<br />

points in common: both involve research on viruses, and<br />

both projects are guided by Marcia Roye’s unrelenting<br />

determination to use science to help people.<br />

Tatiana Lopatina<br />

russia<br />

Jiban Jyoti Panda<br />

iNDia

24<br />

THE IMPACT<br />

OF HUMAN ACTIVITY<br />

ON OUR ECOSYSTEMS<br />

COLOMbIA<br />

Marine ecology<br />

Coral reefs are not only threatened by overfishing,<br />

pollution and climate change, but also by the<br />

devastating effects of Cliona delitrix. This excavating<br />

sponge is capable of modifying the three-dimensional<br />

structure of coral reefs and reducing the amount<br />

of living coral tissue. Yet coral reefs play a vital role,<br />

providing a refuge for fish and protecting the coastline<br />

from waves and currents, thereby slowing erosion. We<br />

now know they can also serve as a potential resource<br />

for new drug molecules.<br />

A PhD student in marine biology, Andia Chaves<br />

Fonnegra, 31, is studying the effects of climate change<br />

on sponge populations and their impact on coral reefs<br />

in the Caribbean Sea. She is researching the timing<br />

of sponge reproduction and its possible correlation<br />

with sea temperature. By comparing the genetic<br />

profiles of neighbouring populations, she will be able<br />

to determine to what extent this species can be used<br />

as a bio-indicator of the deterioration of coral reefs in<br />

the Caribbean Sea.<br />

Andia<br />

Chaves Fonnegra<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center,<br />

Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA<br />

Andia Chaves Fonnegra’s research will<br />

help improve the management of coral<br />

reef restoration projects.<br />

After finishing her PhD, Andia plans<br />

to return to Colombia to continue her<br />

career as a researcher and teacher.<br />

She will focus her work on the potential<br />

of marine organisms as a source of new<br />

drugs for human diseases. Through<br />

her research, she hopes to inspire<br />

future generations to appreciate the<br />

importance of the ocean environment<br />

for human life.<br />

“If politics and the<br />

economy continue<br />

to build a world<br />

that does not take<br />

into account the<br />

preservation of life<br />

as its first objective,<br />

then we are heading<br />

straight toward its<br />

extinction.”

“I hope my research<br />

will eventually make an<br />

important contribution<br />

to the sustainability and<br />

conservation of Costa<br />

Rica’s precious natural<br />

resources.”<br />

IRAQ<br />

Ecology<br />

Today, a quarter of heavy metal pollution<br />

is generated by household waste, such as<br />

NiCad batteries, lead-acid batteries and<br />

the copper and zinc found in pesticides.<br />

These metals have a toxic impact on human<br />

and animal health and are a real threat<br />

to the environment. Unlike organic waste,<br />

heavy metals do not decay over time. They<br />

are ingested and accumulate in the bodies<br />

of animals and humans at each level of the<br />

food chain.<br />

Reyam Al-Malikey, 31, has a PhD in ecology<br />

and now works as an assistant lecturer<br />

in biology at the Al-Mustansiryha University<br />

in Baghdad, Iraq. She is concerned by the<br />

potentially damaging effects of heavy metal<br />

waste, such as cadmium, lead and zinc,<br />

on aquatic ecosystems and their health<br />

implications. This is particularly true in the<br />

southern marshlands of Iraq, which are<br />

undergoing restoration after the ravages of<br />

a government drainage program followed<br />

Isabel Cristina<br />

Chinchilla Soto<br />

COSTA RICA<br />

Ecology<br />

Covering 11.5 million km², tropical forests house over<br />

75% of living species and are a remarkable source of<br />

biodiversity. Numerous studies show how the preservation<br />

of tropical forests, which are often threatened by<br />

deforestation and the opening up of farmland, might help<br />

slow down global warming. Yet, most of these studies<br />

focus on rainforests and little attention has been given to<br />

the role of tropical dry forests, even though they represent<br />

over two thirds of land cover in Latin America and<br />

are just as endangered, notably from fire.<br />

A doctoral student in ecology at the University of Edinburgh,<br />

Scotland, Isabel Cristina Chinchilla-Soto, 32, is<br />

researching the effects of climate change on the carbon<br />

cycle in tropical dry forests.<br />

She will measure the impact of climate change in the dry<br />

forest of Costa Rica’s Santa Rosa National Park, where<br />

she will monitor fluctuations in gas exchange and the leaf<br />

characteristics of various trees. She then plans to analyse<br />

changes in species composition according to the<br />

age of each sampling site. Cristina hopes to demonstrate<br />

that the total carbon storage capacity of forests gradually<br />

increases with age before stabilising in forests over sixty<br />

years old. She will also investigate the ways different tree<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

School of Environmental Studies,<br />

Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada<br />

by the impact of war. The resulting pathologies are often<br />

degenerative diseases such as the diminution of cognitive<br />

faculties, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, and<br />

multiple sclerosis.<br />

Reyam uses geographic information systems (gIS), a<br />

technology combining statistical analysis, visualization<br />

and geographical analysis, as well as field sampling to<br />

establish a correlation between heavy metal concentration<br />

in different levels of the food chain and the nutrient<br />

levels of different marsh areas. She hopes to contribute<br />

to the development of anti-pollution strategies for this<br />

important ecosystem.<br />

When she returns to her university in Iraq, Reyam Al-Malikey<br />

plans to transfer her skills in gIS technology to other<br />

research projects. She would eventually like to set up her<br />

own research team to further explore the impact of pollution<br />

on Iraq’s ecosystems.<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

School of geoSciences,<br />

University of Edinburgh, Scotland, UK<br />

species cope with drought and how they<br />

allocate carbon to their constituent parts<br />

under different environmental conditions.<br />

Her research results will help refine predictions<br />

of changes to the forest ecosystem<br />

and develop vital decision-making tools for<br />

forest conservation and management.<br />

On completion of her PhD, Isabel Cristina<br />

will continue her research career at the<br />

University of Costa Rica, where she looks<br />

forward to sharing her love of science with<br />

the next generation of students.<br />

Reyam<br />

Al-Malikey<br />

“In science, there is<br />

no difference between<br />

men and women.<br />

Successful results<br />

depend on how hard<br />

you work, not on your<br />

gender.”

26<br />

“I hope to serve as<br />

an ambassador for<br />

women in science and<br />

technology in Tunisia.”<br />

Samia<br />

Elfékih<br />

TUNISIA<br />

Molecular biology<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

Faculty of Life Sciences and Medicine, Imperial College<br />

London, Silwood Park, Ascot, UK<br />

Ceratitis capitata, better known as the Mediterranean<br />

fruit fly or medfly, is an insect that can cause<br />

extensive damage to a wide range of fruit crops. A<br />

native of Africa, it has spread invasively to the entire<br />

Mediterranean basin as well as to many other parts of<br />

the world, where it causes severe economic losses<br />

for fruit growers. The insect is not only highly resistant<br />

to several pesticides, but as the climate gradually<br />

warms, there is a risk that the medfly will further<br />

expand its geographical range.<br />

In Tunisia, an agricultural country that has paid heavy<br />

tribute to this insect, Samia Elfékih, 31, with a PhD<br />

in biology from the University of Tunis ElManar,<br />

focuses on the genetic diversity of insect populations.<br />

During her fellowship, Samia Elfékih will try to better<br />

understand how mutant genes coding for resistance<br />

have spread geographically and across diverse<br />

environmental conditions. She will compare gene<br />

sequences from resistant and non-resistant medflies<br />

collected from across the world and examine which<br />

genetic mutations are due to natural evolutionary<br />

adaptation to changing environmental conditions and<br />

which are due to adaptation to insecticide use. She<br />

will then analyse the links between these two types of<br />

evolutionary adaptation to develop better alternatives<br />

to classic pesticides, ones that address changing<br />

climatic conditions and the increasing demand for<br />

eco-friendly solutions.<br />

At the end of her fellowship, Samia<br />

Elfékih will return to Tunisia to take up<br />

a position as associate professor. She<br />

is determined to transfer the technical<br />

skills she acquired during her studies in<br />

the UK and hopes to foster long-term<br />

research collaboration between the two<br />

countries.

Triin<br />

Vahisalu<br />

ESTONIA<br />

Plant molecular biology<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

Division of Plant Biology, University of Helsinki, Finland<br />

In the face of ever dwindling water<br />

resources, a key challenge for the future<br />

of agriculture is the study of droughtresistant<br />

plants. It is vital to research<br />

the mechanisms plants use to adapt to<br />

drought and to identify the specific genes<br />

involved.<br />

With a doctorate in Plant Biology at<br />

the University of Tartu, Estonia and the<br />

University of Helsinki, Triin Vahisalu, 32,<br />

is studying how plants react to changing<br />

environmental conditions.<br />

Leaves are covered with microscopic<br />

pores called stomata. By opening and<br />

closing these pores, plants regulate the<br />

intake of carbon dioxide as a nutrient<br />

and the release of oxygen. To avoid<br />

drying out when not given enough water,<br />

plants close the stomata and slow down<br />

photosynthesis. They are constantly<br />

striving to strike a balance between<br />

maximizing carbon dioxide intake and<br />

minimizing water loss.<br />

Triin Vahisalu has already identified the protein<br />

responsible for the regulation of stomatal closure<br />

in response to drought and ozone pollution, two<br />

factors to which plants are highly sensitive. During<br />

her fellowship, Triin plans to use Arabidopsis plants<br />

from the cabbage family, which grow in sandy soils,<br />

to analyse the mechanisms that activate this protein<br />

when ozone is detected by the plant and that<br />

deactivate the protein when the plant needs to open<br />

its stomata to take in carbon dioxide.<br />

On returning to Estonia, Triin Vahisalu plans to<br />

continue her research in this area and hopes her<br />

findings will eventually lead to the development<br />

of more agricultural crops that are more drought<br />

resistant with lower ozone sensitivity<br />

“With a population of 1.4<br />

million inhabitants, Estonia<br />

has only a few researchers<br />

specialising in plants.<br />

The fellowship provides<br />

invaluable support<br />

that will enable me to<br />

conduct research in a<br />

foreign laboratory.”

28<br />

NATURE: AN ALLY IN<br />

CONTROLLING THE SPREAD<br />

OF HEALTH DISASTERS<br />

germaine L.<br />

Minoungou<br />

bURKINA FASO<br />

Virology<br />

germaine L. Minoungou, 31, defines traditional poultry farming<br />

in Burkina Faso as the ‘‘poor man’s bank’’, but one that<br />

is all too often bankrupted by Newcastle disease, a highly infectious<br />

viral disease. Transmitted by direct contact with infected<br />

birds, contaminated equipment or the air, Newcastle disease<br />

affects all bird species and generates severe economic<br />

losses. Caused by a strain of avian paramyxovirus, Newcastle<br />

disease can lead to 100% mortality in an infected flock of<br />

poultry. Although effective vaccines for the disease exist, they<br />

are rarely used in rural areas because of their cost and the<br />

need to ensure a continuous cold chain for vaccine storage.<br />

germaine Minoungou is convinced of the need to improve<br />

the system for animal disease diagnosis in her country, in<br />

order to enable veterinary staff to differentiate between the<br />

symptoms of Newcastle disease and the often similar symptoms<br />

of avian influenza. This is why she has chosen to spend<br />

her fellowship in a laboratory specializing in these two viral<br />

diseases of birds.<br />

With a doctorate in veterinary medicine, germaine is now preparing<br />

a PhD in virology. She is head of the Virology Service<br />

at the National Laboratory for Livestock Diseases Diagnosis in<br />

HOST INSTITUTION:<br />

Research Center for Animal Hygiene and Food Safety,<br />

University of Obihiro, Hokkaido, Japan<br />

Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, where she is<br />

responsible for the diagnosis of viral disease<br />

in animal stock.<br />

She plans to begin by conducting an epidemiological<br />

study based on an analysis of<br />

poultry samples from across the country.<br />

She will isolate the virus strains found in infected<br />

poultry and analyse them to see whether<br />

those found in Burkina Faso are related to<br />

the strains found in other regions. She hopes<br />

to participate eventually in the development<br />

of a new, low-cost vaccine that could be<br />

stored without special refrigeration.<br />

The young scientist would like her research<br />

to make an important contribution to the well<br />