Motion for a Preliminary Injunction and Memorandum - Wrightslaw

Motion for a Preliminary Injunction and Memorandum - Wrightslaw

Motion for a Preliminary Injunction and Memorandum - Wrightslaw

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

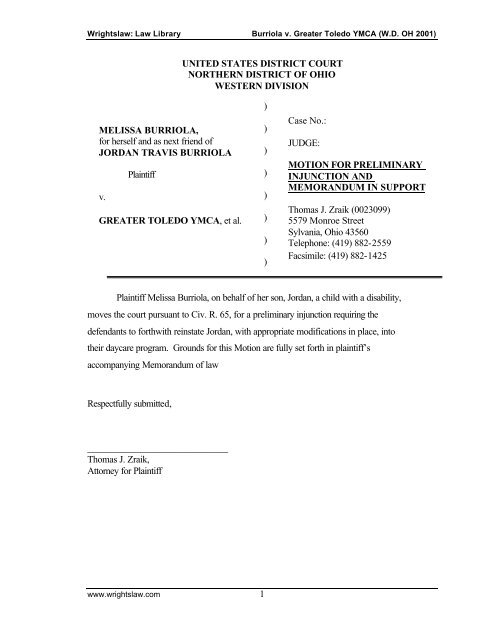

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT<br />

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO<br />

WESTERN DIVISION<br />

MELISSA BURRIOLA,<br />

<strong>for</strong> herself <strong>and</strong> as next friend of<br />

JORDAN TRAVIS BURRIOLA<br />

v.<br />

Plaintiff<br />

GREATER TOLEDO YMCA, et al.<br />

)<br />

)<br />

)<br />

)<br />

)<br />

)<br />

)<br />

)<br />

Case No.:<br />

JUDGE:<br />

MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY<br />

INJUNCTION AND<br />

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT<br />

Thomas J. Zraik (0023099)<br />

5579 Monroe Street<br />

Sylvania, Ohio 43560<br />

Telephone: (419) 882-2559<br />

Facsimile: (419) 882-1425<br />

Plaintiff Melissa Burriola, on behalf of her son, Jordan, a child with a disability,<br />

moves the court pursuant to Civ. R. 65, <strong>for</strong> a preliminary injunction requiring the<br />

defendants to <strong>for</strong>thwith reinstate Jordan, with appropriate modifications in place, into<br />

their daycare program. Grounds <strong>for</strong> this <strong>Motion</strong> are fully set <strong>for</strong>th in plaintiff’s<br />

accompanying Memor<strong>and</strong>um of law<br />

Respectfully submitted,<br />

_____________________________<br />

Thomas J. Zraik,<br />

Attorney <strong>for</strong> Plaintiff<br />

www.wrightslaw.com 1

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR<br />

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION<br />

I. INTRODUCTION<br />

Plaintiff Melissa Burriola brings this action pursuant to Title III of the Americans<br />

With Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. 12180 et seq. (“ADA”), Section 504 of the<br />

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. 794 (“Section 504”), <strong>and</strong> parallel state law seeking<br />

declaratory <strong>and</strong> injunctive relief <strong>and</strong> damages. Plaintiffs allege that defendants have<br />

denied Jordan Burriola the full <strong>and</strong> equal enjoyment of the benefits of, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

opportunity to participate in, defendants’ program, solely on the basis of his disability.<br />

Jordan is seven-years-old <strong>and</strong> will be eight on his birthday, October 10, 2000.<br />

Jordan is a child diagnosed with autism, a pervasive developmental disability commonly<br />

attributed to neurological etiology. Autism is an impairment affecting verbal <strong>and</strong><br />

nonverbal communication, as well as social interaction. Other characteristics often<br />

associated with autism include abnormal sensory responses, engaging in stereotyped<br />

motor movements or mannerisms, <strong>and</strong> resistance or reactivity to environmental changes<br />

or change in daily routine. [See 34 C.F.R. 300.7(c)(1)(I)] Jordan exhibits many typical<br />

characteristics associated with autism including repetitive activities <strong>and</strong> stereotypic<br />

movements <strong>and</strong> echolalia<br />

Jordan’s mother, Melissa Burriola, is employed full time <strong>and</strong> requires daycare <strong>for</strong><br />

her children while she is at work. When school is in session, Jordan typically requires<br />

after-school daycare <strong>for</strong> between two <strong>and</strong> three hours a day. However, when school is<br />

closed during a break, holiday, or <strong>for</strong> inclement weather, Jordan requires full time<br />

daycare. For approximately two years, Mrs. Burriola obtained daycare services <strong>for</strong><br />

Jordan at the Greater Toledo YMCA daycare program operated by a branch affiliate, the<br />

West Family YMCA, on the premises of Calvary United Methodist Church. Officials of<br />

the West Family YMCA notified Mrs. Burriola by letter dated September 6, 2000, that<br />

Jordan would be terminated or “disenrolled” from the daycare program as of September<br />

8, 2000, due to behavior that is inextricably connected to Jordan’s autism. [Exhibit 1:<br />

West Family YMCA September 6, 2000 letter.] Jordan’s removal from the daycare<br />

Copyright © 2001 Peter W. D. Wright 2

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

program was based on his disability <strong>and</strong> defendants’ refusal to provide him with<br />

reasonable modifications, such as had previously proved effective in allowing him to<br />

benefit from <strong>and</strong> to participate in defendants’ childcare program. Thus, defendants<br />

discriminated against Jordan on the basis of his disability <strong>and</strong>, as such, violated federal<br />

<strong>and</strong> state laws guaranteeing persons with disabilities the right to integrate into the<br />

mainstream of society <strong>and</strong> to be free from discrimination.<br />

II FACTS<br />

Jordan Burriola was born October 10, 1992, <strong>and</strong> is the older brother of Michael<br />

Burriola, age six-years. Both reside in Toledo, Ohio, with their mother, Plaintiff Melissa<br />

Burriola.<br />

Jordan was diagnosed at age four-years as having autism. Autism, a pervasive<br />

developmental disability, is considered to be a neurological impairment that is<br />

characterized by significant deficits in verbal <strong>and</strong> nonverbal communication, the<br />

tendency to engage in repetitive <strong>and</strong> stereotyped movements, <strong>and</strong> unusual reactions to<br />

changes in routines or environment. 34 C.F.R. 300.7(c)(1) 1<br />

Jordan’s autism is characterized by many of the same symptoms described above.<br />

For example, he becomes easily frustrated with changes in his daily routines <strong>and</strong> engages<br />

in repetitive activities <strong>and</strong> sensory movements such as h<strong>and</strong> flapping, beating his chest,<br />

pounding his head, <strong>and</strong> running into walls. Jordan also exhibits echolalia on occasion.<br />

Jordan “shuts down” when his senses become overloaded. Shutting down is<br />

characterized by vocalizations or nonsense verbalizations, quick repetitive arm <strong>and</strong> leg<br />

movements, running around in circles, yelling <strong>and</strong> screaming, or crying. [Exhibit 2:<br />

Melissa Burriola Declaration]<br />

Jordan’s autism significantly affects his daily life activities such as learning,<br />

social interaction with peers <strong>and</strong> adults, <strong>and</strong> other major life activities. As a child with<br />

autism, Jordan has been identified as a h<strong>and</strong>icapped child <strong>and</strong> placed into a special<br />

education program <strong>for</strong> children with autism, where he is provided specially designed<br />

instruction <strong>and</strong> related services to meet his unique needs pursuant to the Individuals With<br />

1 See also the “DSM-IV”, Diagnostic <strong>and</strong> Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders, Fourth Ed., American<br />

Psychiatric Association (299.00 Autistic Disorder)<br />

www.wrightslaw.com 3

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

Disabilities Education Act, IDEA, 20 U.S.C. 1401 et seq., <strong>and</strong> Ohio law, ORC § 3323.01<br />

et seq. [Exhibit 3: Jordan’s 2000 – 2001 IEP.]<br />

Jordan attends the M.O.D.E.L. 2 School, which is a community or charter school<br />

under the laws of Ohio, specifically designed to serve autistic children. The purpose of<br />

the M.O.D.E.L. School is limited to providing special education <strong>and</strong> related services to<br />

children with autism. The M.O.D.E.L. School is a public school as that term is defined<br />

under R.C. § 3314.01 <strong>and</strong> as such, it has the same obligation to provide a free appropriate<br />

public education to students with disabilities as any other public school. Jordan has<br />

attended the M.O.D.E.L. School since the 1998 – 1999 school year.<br />

Plaintiff, Mrs. Burriola, is employed from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. <strong>and</strong> there<strong>for</strong>e<br />

both Jordan <strong>and</strong> his brother require after-school daycare services, <strong>and</strong> full time daycare at<br />

times when school is closed. Jordan has attended defendants’ daycare program <strong>for</strong> more<br />

than two years, beginning with the 1998–1999 school year, <strong>and</strong> his brother began<br />

attending the program in September 1999. Mrs. Burriola selected the Greater Toledo<br />

YMCA daycare program because the site is nearest to the plaintiffs’ home <strong>and</strong> because<br />

the program offers tuition on a sliding scale <strong>and</strong> is af<strong>for</strong>dable. The West Family YMCA<br />

branch, located at 2020 Tremainsville Road in Toledo, is a branch affiliate of the Greater<br />

Toledo YMCA <strong>and</strong> operates the daycare program where Jordan <strong>and</strong> his brother were<br />

enrolled. The daycare program itself, however, is conducted on the premises of Calvary<br />

United Methodist Church, located in Toledo at 3939 Jackman Street. In addition to the<br />

after-school daycare, the YMCA program provided full-day childcare <strong>for</strong> both children<br />

during times when school was not in session.<br />

Defendants’ daycare program is licensed to serve fifty-four children, however, as<br />

many as eighty or ninety may be enrolled <strong>for</strong> such services. Eligibility <strong>for</strong> daycare<br />

services is based solely on the availability of space. [Exhibit 4: Jerome Kelly Declaration]<br />

Kathy Miley is the Director of Family Services at the West Family YMCA <strong>and</strong> her<br />

immediate supervisor is Todd Tibbits. The Executive Director of the West Family<br />

YMCA is Henry Presseller. The daycare program is supervised by a Facility Director,<br />

who maintains an on-site office located at the Calvary United Methodist Church. In<br />

addition to the daycare Facility Director, at least two other staff are employed as<br />

2 M.O.D.E.L. is an acronym <strong>for</strong> Multiple Options <strong>for</strong> Developmental & Educational Learning<br />

Copyright © 2001 Peter W. D. Wright 4

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

“counselors” or teachers to provide direct daycare services to the children enrolled in the<br />

program. Fees <strong>for</strong> the daycare are determined on an individual basis according to family<br />

income, the number of daycare hours, <strong>and</strong> the number of children per family enrolled in<br />

the program. An unsubsidized weekly fee ranging from $80.00 to $90.00 per child is<br />

charged if the family’s income exceeds the benchmark established by the agency. In<br />

Jordan’s case, Mr. Burriola paid a monthly fee of approximately $30.00 to $60.00 <strong>for</strong><br />

Jordan’s daycare.<br />

In addition to other government funding, the West Family YMCA received a<br />

$4,000.00 grant <strong>for</strong> summer 2000, through the Toledo Community Recreation<br />

Committee, which distributed funds including $100,000 allocated by the City of Toledo,<br />

in support of youth <strong>and</strong> family programming.<br />

Because of Jordan’s disability, Mrs. Burriola in<strong>for</strong>med the defendants that he<br />

would need some minor accommodations to allow him to be successful at the daycare<br />

program. In fact, the M.O.D.E.L. School offered to provide training to the employees<br />

<strong>and</strong> staff of the daycare program, at no cost, on the nature of autism <strong>and</strong> how to work<br />

with autistic children in general, <strong>and</strong> specifically with Jordan. Administrators at the West<br />

Family YMCA, however, did not make attendance at this training m<strong>and</strong>atory <strong>and</strong> only<br />

two persons directly involved with Jordan elected to attend. [Exhibit 5: Joan McCarthy<br />

Declaration; Exhibit. 4 id.]<br />

The modifications Jordan requires to be successful in the daycare program are<br />

inexpensive <strong>and</strong> minor in nature, requiring primarily that the person or persons<br />

supervising him become in<strong>for</strong>med about autism <strong>and</strong> how to relate to Jordan. [Exhibit 6:<br />

McCarthy August 8, 2000 letter]<br />

Of the two daycare staff who attended the training by the M.O.D.E.L. School, one<br />

left her employment in the daycare program almost immediately <strong>and</strong> the second resigned<br />

from the program approximately one month later. As a result no daycare staff remained<br />

with any training on the topic of autism or how to work with Jordan.<br />

Because no one remaining at the daycare program was willing to become<br />

in<strong>for</strong>med about autism, or trained in working with Jordan, his autistic characteristics<br />

became exacerbated <strong>and</strong> he was ultimately <strong>for</strong>ced out of the program on September 8,<br />

2000. [Exhibit 1, letter. id.]<br />

www.wrightslaw.com 5

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

West Family YMCA officials promised to hire a “teacher” during summer 2000<br />

qualified to work with Jordan <strong>and</strong> other children with disabilities in the daycare program.<br />

No one was ever hired, however, even though funding <strong>for</strong> such a position either was or is<br />

available. Ms. Miley repeatedly attempted to hire unqualified persons to fill this position<br />

<strong>and</strong>, in addition, repeatedly interfered with one (trained) staff member who had attempted<br />

to work with Jordan. [Exhibit 4, Kelly. id.] ] Ms. Miley in<strong>for</strong>med other staff members<br />

that she wanted to get Jordan out of the daycare program because, in her opinion, “he<br />

doesn’t belong here”. [Exhibits 4, Kelly; 5 McCarthy. id.] Ms. Miley, in fact, actively<br />

prevented the modifications <strong>and</strong> accommodations that Jordan needed from being<br />

implemented. [Exhibits 4, Kelly; 2 Burriola. id.]<br />

According to a the <strong>for</strong>mer on-site Facility Director, who provided services to<br />

Jordan <strong>for</strong> approximately one year, with the appropriate modifications in place Jordan is<br />

easily h<strong>and</strong>led <strong>and</strong> behaves normally in the daycare program. [Exhibit 4, Kelly. id.]<br />

Primarily, the persons working with Jordan need to become in<strong>for</strong>med about autism <strong>and</strong> to<br />

provide Jordan the structure <strong>and</strong> guidance he needs.<br />

II ARGUMENT<br />

In order to prevail on the motion <strong>for</strong> a preliminary injunction, the court must<br />

consider, (1) plaintiffs’ likelihood of success on the merits of the claim, (2) whether the<br />

plaintiffs will suffer irreparable harm, (3) the probability of substantial harm to others <strong>and</strong><br />

(4) whether the public interest is advanced. Washington v. Reno, 35 F.3d 1093, 1099<br />

(6 th Cir. 1994). These are not prerequisites but rather “factors to be balanced” In Re<br />

Delorian Motor Co., 755 F.2d 1223, 1229(6 th Cir. 1985).<br />

None of the four factors is to be deemed conclusive on its own “<strong>and</strong>” each<br />

need not be viewed in isolation from the others, solely as an independent<br />

variable.” Blue Cross & Blue shield Mutual Of Ohio v. Columbia /HC4<br />

Healthcare et al, 110 F.3d 318, 334 (6 th Cir.1997).<br />

The issues presented <strong>for</strong> review in the context of this motion are relatively clear.<br />

The court must determine whether or not the plaintiffs are likely to succeed on their<br />

claims that the defendants illegally terminated Jordan from the daycare program operated<br />

by the West Family YMCA, <strong>and</strong> that the defendants failed to maintain or provide<br />

Copyright © 2001 Peter W. D. Wright 6

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

reasonable modifications to its policies, practices <strong>and</strong> procedures to allow Jordan to<br />

benefit from <strong>and</strong> to participate in the daycare program operated by the defendants.<br />

The Plaintiffs have Shown A Likelihood Of Success On The Merits As Indisputable<br />

Facts Show That The Plaintiffs Are Entitled To Relief Under The ADA<br />

The plaintiffs’ burden regarding likelihood of success on the merits is to show,<br />

“sufficiently serious questions going to the merits to make them a fair ground <strong>for</strong><br />

litigation <strong>and</strong> a balance of hardships tipping decidedly towards the party<br />

requesting the preliminary relief.” Farm Labor Organizing Committee v. Ohio<br />

Highway Patrol, 991 F. Supp. 895, 900 (N.D. Ohio 1997).<br />

In this case, the plaintiffs must show that Jordan is qualified <strong>for</strong> defendants’ daycare<br />

program <strong>and</strong> was either denied a reasonable modification, or an adverse decision was<br />

made against him on the basis of his disability. McPherson v. Michigan High School<br />

Athletic Ass'n, Inc., 119 F.3d 453, 460 (6th Cir. 1997). citing Roush v. Weastec Inc. 96<br />

F3d 840 (6 th Cir. 1996). The showing <strong>for</strong> discrimination under the ADA is similar to that<br />

under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, <strong>and</strong> construing the cases in one is instructive<br />

<strong>for</strong> construing cases under the other. Andrews v. State of Ohio 194 F3d 803, 807 (6 th Cir.<br />

1997). Further, the 6 th Circuit recently stated that while the st<strong>and</strong>ards used in Section 504<br />

<strong>and</strong> the ADA are largely the same, there are differences. For example, in Title III of the<br />

ADA, the phrase “solely by reason of” is not mentioned. McPherson id. p. 465 In large<br />

part this distinction is meaningless since the plaintiff here need only establish that he is<br />

disabled <strong>and</strong> is either discriminated against on the basis of his disability or was denied a<br />

reasonable accommodation. McPherson at pg. 466<br />

Jordan is a person with a disability <strong>and</strong> the defendants, a private entity providing<br />

public accommodations, have excluded Jordan from, <strong>and</strong> denied him the benefits of the<br />

defendants programs, services or activities on the basis of his disability or have otherwise<br />

subjected him to discrimination. There can be no dispute that Jordan Burriola is a<br />

“qualified individual with a disability” under the ADA. The term “disability” is defined<br />

in the Act as:<br />

“* * * any physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of<br />

the major life activities of the individual.”<br />

See 42 U.S.C. 12102(2); see also 28 C.F.R. 36.104; 28 C.F.R. 35.104.<br />

www.wrightslaw.com 7

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

The term “physical or mental impairment” means any physiological, or mental disorder<br />

affecting body systems, including neurological, special sense organs, respiratory,<br />

cardiovascular <strong>and</strong> digestive. The term “major life activities” means functions such as<br />

caring <strong>for</strong> one’s self, per<strong>for</strong>ming manual tasks, walking, seeing, hearing, speaking,<br />

breathing, learning <strong>and</strong> working. Id<br />

Jordan’s autism affects his ability to communicate effectively with his peers <strong>and</strong><br />

adults, to interact appropriately with his peers <strong>and</strong> adults, <strong>and</strong> causes him to engage in,<br />

stereotypic sensory movements, repetitive activities <strong>and</strong> other types of atypical behavior.<br />

[Exhibits 2, Burriola; 4, Kelly; 5 McCarthy. id.] In addition, Jordan is identified as a<br />

h<strong>and</strong>icapped child <strong>and</strong> is provided special education <strong>and</strong> related services to meet his<br />

unique disability needs, pursuant to the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act,<br />

(IDEA) 20 U.S.C. 1400 et seq., <strong>and</strong> Revised Code Section 3323.01 et seq. These services<br />

are provided to Jordan at the M.O.D.E.L. School, a Community School charted by the<br />

State of Ohio pursuant to R.C. 3323.01. The M.O.D.E.L. School provides special<br />

education <strong>and</strong> related services to students diagnosed <strong>and</strong> identified pursuant to the IDEA<br />

as having autism. [Exhibits 3, IEP; 5, McCarthy. id] Furthermore, Mrs. Burriola states<br />

that, in comparison with same-aged peers, Jordan requires more close supervision,<br />

consistency, structure in his environment, <strong>and</strong> highly organized activities at home due to<br />

his disability. [Exhibit 2, Burriola id.] Because Jordan functioned successfully in<br />

defendants’ daycare program when provided with appropriate supervision by in<strong>for</strong>med<br />

staff, there can be no question that he meets the essential eligibility requirements <strong>for</strong><br />

entry into <strong>and</strong> continued participation in defendants’ daycare program. The application<br />

<strong>and</strong> enrollment requirements <strong>for</strong> the daycare program require simply that the child be<br />

between the ages of five <strong>and</strong> twelve year, <strong>and</strong> that there is space available. No other<br />

eligibility criteria exist. [Exhibit 2, Burriola id.]<br />

It is also extremely likely that the plaintiffs can show “sufficiently serious<br />

questions going to the merits of the case to make them a fair ground <strong>for</strong> litigation, <strong>and</strong> a<br />

balance of hardships tipping decidedly towards the party requesting the preliminary<br />

relief”. The question of whether the defendants, as a place of public accommodations,<br />

illegally excluded Jordan from participation in, or denied him the benefits of the<br />

defendants’ services, programs or activities, or otherwise subjected him to discrimination<br />

Copyright © 2001 Peter W. D. Wright 8

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

is addressed in the Act at 42 U.S.C. 12182, <strong>and</strong> in 28 C.F.R. 36.201 et seq. As mirrored<br />

by the regulation, the Act states:<br />

“(a) General Rule. No individual shall be discriminated against on the basis of<br />

disability in the full <strong>and</strong> equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities,<br />

privileges, advantages, or accommodations of any place of public<br />

accommodations by any person who owns, leases {or leases to}, or operates a<br />

place of public accommodations.”<br />

In reference to Denial of Participation, 42 U.S.C. 12182(b)(1)(A)(I), in part, states:<br />

“It shall be discriminatory to subject an individual… with a disability or<br />

disabilities, on the basis of a disability…of such individual…directly or through<br />

contractual, licensing, or other arrangements, to a denial of the opportunity of the<br />

individual… to participate in or benefit from the gods, services, facilities,<br />

privileges, advantages, or accommodations of an entity.”<br />

Section II of the above section addresses Participation in Unequal Benefits, as follows:<br />

“It shall be discriminatory to af<strong>for</strong>d an individual … on the basis of a disability or<br />

disabilities of such individual…directly or through contractual licensing or other<br />

arrangements with the opportunity to participate in or benefit from a good,<br />

service, facility, privilege, advantage, or accommodation that is not equal to that<br />

af<strong>for</strong>ded to other individuals.” Id<br />

Subsection (b)(1)(D), Administrative Methods, further states:<br />

“An individual or entity shall not, directly or by contractual, licensing or other<br />

arrangements, utilize st<strong>and</strong>ards or criteria or methods of administration (I) that<br />

have the effect of discriminating on the basis of disability…”. Id.<br />

Subsection (E), Association, 42 U.S.C. 182(b)(1) also states:<br />

“It shall be discriminatory to exclude or otherwise deny equal goods, services,<br />

facilities, privileges, advantages, accommodations, or other opportunities to an<br />

individual or entity because of the known disability of an individual with whom<br />

the individual or entity is known to have a relationship or association.” Id.<br />

Specific prohibitions against discrimination towards persons with disabilities are found at<br />

42 U.S.C. 12182(b)(2). Subsections (b)(2)(A) (I through III) specifically preclude a place<br />

of public accommodations from discriminating against individuals with disabilities by:<br />

“I. [I]mposing eligibility or other or application criteria that screen out or tend to<br />

screen out individuals with disabilities from fully <strong>and</strong> equally enjoying the goods<br />

services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations, unless such<br />

criteria can be shown to be necessary <strong>for</strong> the provision of such goods, services…<br />

being offered;<br />

www.wrightslaw.com 9

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

II [F]ailure to make reasonable modifications to the policies, practices, or<br />

procedures when such modifications are necessary to af<strong>for</strong>d such goods, services,<br />

facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations to individuals with<br />

disabilities, unless the entity can demonstrate making such modifications would<br />

fundamentally alter the nature of such goods, services, facilities, privileges,<br />

advantages or accommodations;” <strong>and</strong><br />

III [F]ailure to take such steps as may be necessary to ensure that no individual<br />

with a disability is excluded, denied services, segregated or otherwise treated<br />

differently than other individuals because of the absence of auxiliary aids <strong>and</strong><br />

services, unless the entity can demonstrate that taking such steps would<br />

fundamentally alter the nature the goods, services, facilities, privileges,<br />

advantages or accommodations being offered, or would result in an undue<br />

burden….”<br />

The regulations at 28 C.F.R. 36.201, 202, 203, 204 <strong>and</strong> 28 C.F.R. 36.301, 302 <strong>and</strong> 303<br />

more fully interpret <strong>and</strong> implement the requirements <strong>and</strong> prohibitions contained in 42<br />

U.S.C. 12182 as described above.<br />

In short, the defendants may not discriminate against Jordan by denying him the<br />

full <strong>and</strong> equal participation in the daycare program on the basis of his disability, <strong>and</strong> must<br />

ensure that his participation in the daycare program is in the most integrated setting<br />

appropriate. Further, the defendants must not apply any application or eligibility criteria<br />

that may serve to screen Jordan out from participation in the daycare program; must make<br />

reasonable modifications to its policies, practices <strong>and</strong> procedures that would allow Jordan<br />

to enjoy the benefits of defendants’ daycare program; <strong>and</strong> must take all steps necessary so<br />

as not to exclude Jordan from participation in the daycare program as the result of not<br />

having available auxiliary aids <strong>and</strong> services, unless the defendants can demonstrate that<br />

the criteria, or policies, practices <strong>and</strong> procedures, or provision of auxiliary aids <strong>and</strong><br />

services would fundamentally alter the nature of the daycare program or pose an undue<br />

burden to the defendants.<br />

Applying the statutory <strong>and</strong> regulatory requirements listed above to the present<br />

facts demonstrates that the plaintiffs are likely to succeed on the merits. It is undisputed<br />

that Jordan was terminated from the daycare program operated <strong>and</strong> administered by the<br />

defendants, thus denying him full <strong>and</strong> equal participation in the benefits, services,<br />

facilities, privileges, advantages <strong>and</strong> accommodations provided by the YMCA daycare<br />

program. [Exhibit 2, Burriola. id.] Jordan cannot enjoy the benefits of the daycare<br />

Copyright © 2001 Peter W. D. Wright 10

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

program unless the staff who supervise him are in<strong>for</strong>med about the nature <strong>and</strong> affects of<br />

autism, <strong>and</strong> trained on techniques <strong>and</strong> interventions appropriate <strong>for</strong> Jordan. [Exhibit 5,<br />

McCarthy id.] Jordan has demonstrated that the manifestations of his autism are well<br />

managed when staff become in<strong>for</strong>med <strong>and</strong> implement the reasonable modifications<br />

suggested by Jordan’s special education teachers, <strong>and</strong> previously used effectively when<br />

implemented at the defendants’ daycare program. [Exhibit 4, Kelly id.] Thus, even<br />

though Jordan has previously demonstrated his ability to enjoy the benefits of the daycare<br />

program with reasonable modifications, defendants have <strong>and</strong> continue to refuse to<br />

provide these reasonable modifications <strong>and</strong>, instead, terminated him from the daycare<br />

program.<br />

The defendants are required to provide reasonable modifications to its policies,<br />

practices <strong>and</strong> procedures, unless they can demonstrate that such modifications would<br />

fundamentally alter the nature of the daycare program. Defendants’ letter to plaintiff,<br />

Melissa Burriola, in<strong>for</strong>ming her on September 6, 2000, that Jordan was to be terminated<br />

from the daycare program as of September 8, 2000, did not raise the issue that making<br />

reasonable modifications to its policies, practices <strong>and</strong> procedures would fundamentally<br />

alter the nature of the daycare program. The issue was not raised because under the facts<br />

of this case the defendants cannot reasonably make that argument. In fact, it has been<br />

clearly demonstrated that with such reasonable modifications Jordan can successfully<br />

enjoy the benefits of the daycare program <strong>and</strong> is able to participate in it as any other<br />

child. [Exhibits 4, Kelly; 5 McCarthy id.] The modifications that are necessary <strong>and</strong><br />

which would allow Jordan to benefit from the defendants daycare program are<br />

reasonable, not very time consuming <strong>and</strong> inexpensive. Jordan requires personnel<br />

working with him <strong>and</strong>/or supervising him to become in<strong>for</strong>med about the nature of autism<br />

<strong>and</strong> the effect it has on Jordan’s social functioning. In addition, persons working with<br />

Jordan need to implement modifications similar to the recommendations made by Joan<br />

McCarthy, who has worked directly with Jordan in his special education program at the<br />

M.O.D.E.L. School <strong>and</strong>, in addition, personally observed Jordan in the daycare program,<br />

provided training to two YMCA daycare workers, <strong>and</strong> developed a written plan <strong>for</strong><br />

Jordan’s daycare. The modifications include, in part:<br />

www.wrightslaw.com 11

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

?? … a consistent, visual schedule of each day’s activities (Jordan will be<br />

relieved to have a schedule of activities made <strong>for</strong> him as the organization<br />

of time is very difficult <strong>for</strong> him, as is initiating play with other children);<br />

?? Simple board games (C<strong>and</strong>y L<strong>and</strong>, Hi-Ho-Cherryio, Shoots <strong>and</strong><br />

Ladders),simple card games (Old Maid, Go Fish, War);<br />

?? …more time playing with the Nintendo be scheduled <strong>for</strong> Jordan than the<br />

10 minutes currently allotted. Playing Nintendo is an area of strength <strong>for</strong><br />

Jordan <strong>and</strong> it is where he is able to demonstrate age-appropriate social<br />

skills ) assisting other children…giving high-fives, etc.;<br />

?? Visuals …to redirect Jordan. Visuals … [<strong>for</strong> example] include “Quiet<br />

H<strong>and</strong>s”, “Self-Control”, “Sit Quietly”, “Check Schedule”, <strong>and</strong> “Share”;<br />

?? … Jordan [should] be af<strong>for</strong>ded a “Break” location when the staff [see] …<br />

physical signs that Jordan [is] having difficulty regulating his behaviors.<br />

These physical signs include Jordan’s verbal communication becoming<br />

confused <strong>and</strong> louder, more movement of his arms <strong>and</strong> legs, <strong>and</strong> crying<br />

sounds or actual crying;<br />

?? …staff need to reduce their auditory input to Jordan when he demonstrates<br />

these physical signs <strong>and</strong> redirect with the above-mentioned visuals<br />

[Exhibit 6, McCarthy letter. id]<br />

These modifications may seem inconvenient initially, but they are not unreasonable.<br />

However, it is clear they are necessary to enable Jordan to enjoy the benefits of the<br />

daycare program.<br />

Interestingly, while the defendants do not appear to raise the argument that<br />

Jordan’s modifications would fundamentally alter the nature of the daycare program, the<br />

letter terminating him appears to raise an argument along the lines that Jordan’s<br />

attendance at the daycare program would pose a {direct threat} to the safety of others that<br />

a reasonable accommodation would not mitigate. The September 6, 2000 letter suggests<br />

that Jordan was terminated because he hit or struck other children in the program on<br />

several occasions <strong>and</strong>, on one occasion, went onto a l<strong>and</strong>ing between floors <strong>and</strong> held a<br />

door closed so that a staff person could not open it by herself, suggesting his behavior put<br />

Jordan at risk. [Exhibit 1, West YMCA letter. id.] The direct threat defense is found in<br />

the statute at 42 U.S.C. 12182(b)(3) <strong>and</strong> states:<br />

Nothing in this title shall require an entity to permit an individual to participate in<br />

or benefit from the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, <strong>and</strong><br />

accommodations of such entity, where such individual poses a direct threat to the<br />

health or safety of others.<br />

Copyright © 2001 Peter W. D. Wright 12

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

The term “direct threat” means a significant risk to the health or safety of others<br />

that cannot be limited by a modification of the policies, practices or procedures or by the<br />

provision of auxiliary aids or services. The regulation implementing this statutory<br />

provision helps clarify the intent of the provision. The comment to the regulation states in<br />

pertinent part,<br />

The inclusion of this provision is not intended to imply that persons with<br />

disabilities pose risks to others. It is intended to address concerns that may arise<br />

in this area. [It establishes a strict st<strong>and</strong>ard that must be met be<strong>for</strong>e denying<br />

services to an individual with a disability or excluding that individual from<br />

participation.] 28 C.F.R. 36.208 comment.<br />

The rule requires that places of public accommodation determine whether an individual<br />

poses a direct threat by engaging in an individualized process, utilizing reasonable<br />

judgment that relies on current medical knowledge or on the best available objective<br />

evidence, to ascertain: the nature, duration <strong>and</strong> severity of the risk; the probability that the<br />

potential injury will actually occur; <strong>and</strong> whether reasonable modifications of policies,<br />

practices <strong>and</strong> procedures will mitigate the risk. 28 C.F.R. 36.208(c). Applying this<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard to the present case clearly demonstrates that the defendants have not <strong>and</strong> cannot<br />

meet the burden of establishing Jordan poses a direct threat to the health or safety of<br />

others at the daycare program.<br />

The daycare program’s <strong>for</strong>mer Facility Director, Mr. Jerry Kelley, who worked<br />

closely with Jordan from August 1999 through August 2000, has provided sworn<br />

statements that Jordan posed no risk of safety to others when the modifications<br />

recommended by Jordan’s teachers were implemented. [Exhibit 4, Kelly. id.] Mr. Kelley<br />

also states that his ability to work with Jordan <strong>and</strong> freedom to implement modifications<br />

<strong>for</strong> him were significantly impeded by the West Family YMCA’s Director of Family<br />

Services, Kathy Miley. Ms. Miley directly ordered Mr. Kelley to discontinue spending<br />

any one-to-one time working with Jordan, <strong>and</strong> failed or refused to hire a qualified teacher<br />

or instructor to work with Jordan <strong>and</strong> other special needs children enrolled in the daycare<br />

program. [Exhibit 4, Kelly. id.] It was only after Mr. Kelley resigned <strong>and</strong> left, <strong>and</strong> no<br />

staff remained in the daycare program who were trained or willing to use the previously<br />

successful modifications required, that Jordan’s ability to participate was compromised<br />

<strong>and</strong> began to deteriorate until he was ultimately dismissed from the daycare program.<br />

www.wrightslaw.com 13

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

Obviously, the defendants failed to comply with any of the st<strong>and</strong>ards imposed on them by<br />

28 C.F.R. 36.208 when terminating Jordan from the daycare program.<br />

The Balance Of Hardships Tip Decidedly To The Plaintiffs.<br />

The only hardships the defendants can claim are the costs, if any, of training<br />

current <strong>and</strong> future staff employees to recognize <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> the characteristics of<br />

autism <strong>and</strong> the relatively minor inconvenience of implementing the modifications<br />

recommended by the M.O.D.E.L. School.<br />

In contrast, plaintiffs will undeniably suffer the complete loss of necessary<br />

daycare services <strong>for</strong> Jordan. Jordan will be denied the opportunity to learn appropriate<br />

socialization skills outside the school setting, <strong>and</strong> will be completely denied the<br />

opportunity to be integrated with non-disabled children in a daycare setting. In addition,<br />

plaintiffs will be <strong>for</strong>ced to seek costly “special” daycare services designed specifically <strong>for</strong><br />

children with special needs. These services are not only more costly than the services<br />

provided by the defendants, but they are extremely hard if not impossible to find. If<br />

found, in most cases a long waiting list <strong>for</strong> enrollment exist.<br />

Based on the <strong>for</strong>egoing, the plaintiffs have shown sufficiently serious questions<br />

going to the merits to make them a fair ground <strong>for</strong> litigation <strong>and</strong> have demonstrated<br />

clearly that the balance of hardships unquestionably favors the plaintiffs. Plaintiffs have<br />

thus established likelihood they will succeed on a trial of the merits.<br />

Jordan Burriola Will Suffer Irreparable harm If He Is Not Allowed To Participate<br />

In The Defendants’ Daycare Program.<br />

The harm suffered by Jordan as a result of being dismissed <strong>and</strong> totally excluded<br />

from defendants’ daycare program where he had attended <strong>for</strong> two years is immediate,<br />

irreparable <strong>and</strong> ongoing. Relevant to the issue presented here is the fact that several<br />

courts have found that the exclusion of students with disabilities from school sports<br />

activities were likely to result in irreparable harm, because of the negative effect of such<br />

exclusion on socialization. S<strong>and</strong>ison v. Michigan High School Athletic Assn., 863 F.<br />

supp. 483, 491(E.D. Mich.1994); Denin v. Interscholastic Athletic Assn., 913 F. Supp.<br />

Copyright © 2001 Peter W. D. Wright 14

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

663, 667, (D. Xco. 1996); Johnson v. Florida High School Activities Assn., Inc., 899 F.<br />

Supp. 579, 586, (M.D. Fla. 1995).<br />

In this case, plaintiffs have clearly shown the harm to Jordan, socially <strong>and</strong><br />

educationally, resulting from defendants denying him the opportunity to participate in<br />

<strong>and</strong> enjoy the benefits of the daycare program provided by the defendants. As a child<br />

with autism it is particularly important <strong>for</strong> Jordan’s development that he have consistent<br />

<strong>and</strong> constant interaction with non-disabled children, along with the necessary<br />

supervision, <strong>and</strong> training of the staff working with him to aid in appropriate socialization<br />

activities. Denying him this opportunity, will <strong>for</strong>ce Jordan to seek daycare services from<br />

agencies serving only the disabled, thus delaying any opportunity to learn appropriate<br />

social skills. In addition, Jordan is expected to be able to be integrated into a “regular”<br />

school <strong>for</strong> the 2001-2002 school year. [Exhibit 5 id.] The effect upon Jordan of removing<br />

him from his integrated daycare program may have further negative impact on this. The<br />

net result to Jordan is that he has <strong>and</strong> continues to suffer daily irreparable harm by the<br />

defendants’ illegal conduct in removing him from his daycare program.<br />

Considering the factor of irreparable harm, within the context of this motion, the<br />

question of whether the harm can be fully compensated by money damages is relevant.<br />

“[A] plaintiff’s harm is not irreparable if it can be fully compensable by money<br />

damages. However, an injury is not fully compensable by money damages if the<br />

nature of the plaintiff’s loss would make damages difficult to calculate.” Basic<br />

Computer Corp. v. Scott, 973 F.2d 507, 511, (6 th Cir. 1992); See also Dennin v.<br />

Conn. Interscholastic Athletic Assn., supra, 913 f. Supp. at 667; 11 A. Wright<br />

<strong>and</strong> Miller Federal Practice <strong>and</strong> Procedure, Sec. 2948. 1, n 1221, (1995); Moore’s<br />

Federal Practice 2’d at Sec. 65.04(1)(A) no. 66, 68,69, 72.<br />

Jordan has <strong>and</strong> continues to suffer irreparable harm by being totally excluded from the<br />

defendants’ daycare program. The harm of being excluded from an integrated setting<br />

with children who are not disabled, the loss of learning <strong>and</strong> opportunity to model<br />

appropriate interpersonal social behavior cannot easily be measured in terms of money<br />

damages. Further, as the 6 th Circuit has recognized, the requirement of irreparable harm<br />

is met when the plaintiff’s injuries “are the very type of injuries Congress tried to avoid.”<br />

E.E.O.C. v. Chrysler Corp. 733 F. 2’d 1183, 1186, (6 th Cir. 1998). The purpose of the<br />

ADA is to<br />

www.wrightslaw.com 15

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

“..provide a clear <strong>and</strong> comprehensive national m<strong>and</strong>ate <strong>for</strong> the elimination of<br />

discrimination against individuals with disabilities” [<strong>and</strong> to provide] "clear,<br />

strong, consistent en<strong>for</strong>ceable st<strong>and</strong>ards addressing discrimination against<br />

individuals with disabilities;” [<strong>and</strong> to ensure] “the federal government plays a<br />

central role in en<strong>for</strong>cing the st<strong>and</strong>ards established by this act on behalf of<br />

individuals with disabilities” [<strong>and</strong> finally] ” to invoke the sweep of congressional<br />

authority, including the power to en<strong>for</strong>ce the Fourteenth Amendment <strong>and</strong> to<br />

regulate commerce, in order to address the major areas of discrimination faced<br />

day to day by persons with disabilities”. 42 U.S.C. 12101(b).<br />

It is obvious that none of these purposes can be accomplished if a place of public<br />

accommodation, in this case the defendants’ daycare program, is free to discriminate<br />

against Jordan. The defendants’ daycare program is a place of public accommodation as<br />

that term is defined by 42 U.S.C. 12181(6)(7)(K). The congressional intent to af<strong>for</strong>d full<br />

<strong>and</strong> equal opportunities to persons with disabilities to participate in the mainstream of<br />

society begins at the time when disabled children are first enrolled in a nursery or daycare<br />

program such as the defendants. To allow disabled children to be excluded at the very<br />

time integration can have the most beneficial impact would significantly frustrate the<br />

intent of congress to end discrimination against persons with disabilities.<br />

The Defendants Can Make No Showing Of Substantial Harm To Others.<br />

It is unimaginable how requiring the defendants to reinstate Jordan into the<br />

daycare program will cause substantial harm to others, in particular, where his<br />

reinstatement would be accompanied with the modifications necessary to ensure his<br />

successful enjoyment of the program. As argued above, these modifications are not time<br />

consuming <strong>and</strong> may pose a mild inconvenience, at most, to staff. Moreover, the<br />

modifications are inexpensive <strong>and</strong> have a record of demonstrated success when provided<br />

to Jordan earlier during his enrollment there.<br />

The Public Interest Is Advanced By Requiring The Defendants To Provide Jordan<br />

With The Necessary Modifications That Will Allow Him To Attend The Daycare<br />

Program Successfully.<br />

Requiring the defendants to reinstate Jordan along with the modifications he<br />

needs to be successful furthers the public interest <strong>and</strong> the intent required by congress in<br />

adopting the ADA. Regarding this factor this court has found that<br />

Copyright © 2001 Peter W. D. Wright 16

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

“ guarding against violations of… federal law serves the public interest.” Farm<br />

Labor Organizing Committee supra, 991 F. Supp. at 907.<br />

Similarly, S<strong>and</strong>ison v. Michigan High School Athletic Assn., supra, stated<br />

“The purpose of the ADA … is to include persons with disabilities in society,<br />

equal to those without disabilities by addressing discrimination against persons<br />

with disabilities. 42 U.S.C.A. sec. 12101 [<strong>and</strong>] There is significant public<br />

interest in eliminating discrimination against persons with disabilities…” 863 F.<br />

Supp. at 491.<br />

Requiring defendants to readmit Jordan to the daycare program <strong>and</strong> to provide<br />

him with necessary modifications will certainly be within the public interest, especially<br />

since the defendants receive public money to help operate its programs in the <strong>for</strong>m of<br />

government grants.<br />

IV CONCLUSION<br />

Considering the facts <strong>and</strong> arguments presented herein, the plaintiffs have shown<br />

that they are entitled to a preliminary injunction requiring the defendants to readmit<br />

Jordan into the West Family YMCA daycare program <strong>and</strong> to provide the necessary<br />

modifications he requires to participate successfully in the daycare program<br />

Respectfully submitted,<br />

_____________________<br />

Thomas J. Zraik<br />

Attorney <strong>for</strong> Plaintiffs<br />

www.wrightslaw.com 17

<strong>Wrightslaw</strong>: Law Library Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

Links: Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA (W.D. OH 2001)<br />

Decision in pdf<br />

Decision in html<br />

Closing Arguments in Burriola v. Greater Toledo YMCA by Attorney Thomas J.<br />

Zraik<br />

Why This Case is Important by Thomas J. Zraik, Esq.<br />

Analysis by Peter W. D. Wright, Esq.<br />

To Caselaw Library<br />

To Main Law Library<br />

Home<br />

Copyright © 2001 Peter W. D. Wright 18