SR Vol 27 No 3, July 2009 - Nova Scotia Barristers' Society

SR Vol 27 No 3, July 2009 - Nova Scotia Barristers' Society

SR Vol 27 No 3, July 2009 - Nova Scotia Barristers' Society

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

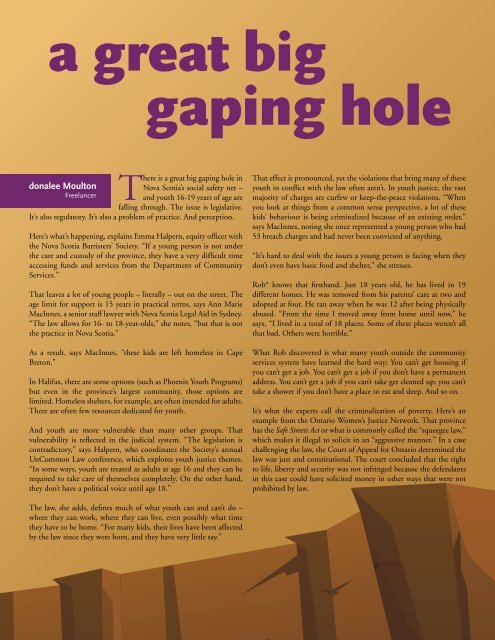

a great big<br />

gaping hole<br />

There is a great big gaping hole in<br />

donalee Moulton<br />

<strong>No</strong>va <strong>Scotia</strong>’s social safety net –<br />

Freelancer<br />

and youth 16-19 years of age are<br />

falling through. The issue is legislative.<br />

It’s also regulatory. It’s also a problem of practice. And perception.<br />

Here’s what’s happening, explains Emma Halpern, equity officer with<br />

the <strong>No</strong>va <strong>Scotia</strong> Barristers’ <strong>Society</strong>. “If a young person is not under<br />

the care and custody of the province, they have a very difficult time<br />

accessing funds and services from the Department of Community<br />

Services.”<br />

That leaves a lot of young people – literally – out on the street. The<br />

age limit for support is 15 years in practical terms, says Ann Marie<br />

MacInnes, a senior staff lawyer with <strong>No</strong>va <strong>Scotia</strong> Legal Aid in Sydney.<br />

“The law allows for 16- to 18-year-olds,” she notes, “but that is not<br />

the practice in <strong>No</strong>va <strong>Scotia</strong>.”<br />

As a result, says MacInnes, “these kids are left homeless in Cape<br />

Breton.”<br />

In Halifax, there are some options (such as Phoenix Youth Programs)<br />

but even in the province’s largest community, those options are<br />

limited. Homeless shelters, for example, are often intended for adults.<br />

There are often few resources dedicated for youth.<br />

And youth are more vulnerable than many other groups. That<br />

vulnerability is reflected in the judicial system. “The legislation is<br />

contradictory,” says Halpern, who coordinates the <strong>Society</strong>’s annual<br />

UnCommon Law conference, which explores youth justice themes.<br />

“In some ways, youth are treated as adults at age 16 and they can be<br />

required to take care of themselves completely. On the other hand,<br />

they don’t have a political voice until age 18.”<br />

That effect is pronounced, yet the violations that bring many of these<br />

youth in conflict with the law often aren’t. In youth justice, the vast<br />

majority of charges are curfew or keep-the-peace violations. “When<br />

you look at things from a common sense perspective, a lot of these<br />

kids’ behaviour is being criminalized because of an existing order,”<br />

says MacInnes, noting she once represented a young person who had<br />

53 breach charges and had never been convicted of anything.<br />

“It’s hard to deal with the issues a young person is facing when they<br />

don’t even have basic food and shelter,” she stresses.<br />

Rob* knows that firsthand. Just 18 years old, he has lived in 19<br />

different homes. He was removed from his parents’ care at two and<br />

adopted at four. He ran away when he was 12 after being physically<br />

abused. “From the time I moved away from home until now,” he<br />

says, “I lived in a total of 18 places. Some of these places weren’t all<br />

that bad. Others were horrible.”<br />

What Rob discovered is what many youth outside the community<br />

services system have learned the hard way: You can’t get housing if<br />

you can’t get a job. You can’t get a job if you don’t have a permanent<br />

address. You can’t get a job if you can’t take get cleaned up; you can’t<br />

take a shower if you don’t have a place to eat and sleep. And so on.<br />

It’s what the experts call the criminalization of poverty. Here’s an<br />

example from the Ontario Women’s Justice Network. That province<br />

has the Safe Streets Act or what is commonly called the “squeegee law,”<br />

which makes it illegal to solicit in an “aggressive manner.” In a case<br />

challenging the law, the Court of Appeal for Ontario determined the<br />

law was just and constitutional. The court concluded that the right<br />

to life, liberty and security was not infringed because the defendants<br />

in this case could have solicited money in other ways that were not<br />

prohibited by law.<br />

The law, she adds, defines much of what youth can and can’t do –<br />

where they can work, where they can live, even possibly what time<br />

they have to be home. “For many kids, their lives have been affected<br />

by the law since they were born, and they have very little say.”<br />

18 The <strong>Society</strong> Record