MAXIMUM EFFICIENCY MINIMUM EFFORT - Kelly Crigger

MAXIMUM EFFICIENCY MINIMUM EFFORT - Kelly Crigger

MAXIMUM EFFICIENCY MINIMUM EFFORT - Kelly Crigger

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

JUDO<br />

<strong>MAXIMUM</strong><br />

<strong>EFFICIENCY</strong><br />

<strong>MINIMUM</strong><br />

<strong>EFFORT</strong><br />

Judo is still a practical martial art<br />

by KELLY CRIGGER<br />

// PHOTOS COURTESY THE KODOKAN INSTITUTE<br />

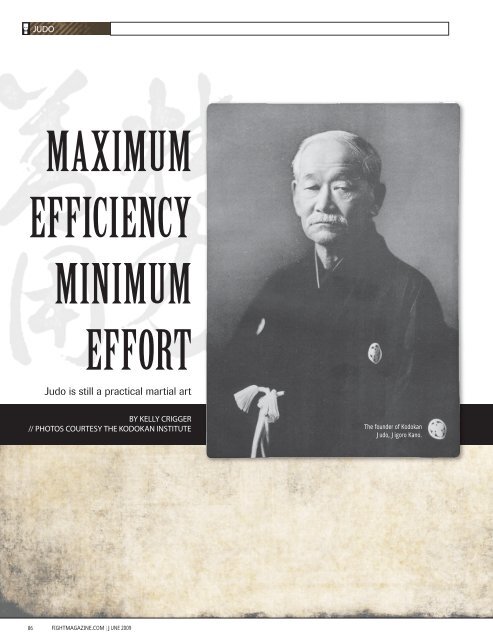

The founder of Kodokan<br />

Judo, Jigoro Kano.<br />

86 FIGHTMAGAZINE.COM | JUNE 2009

JUDO<br />

“Your Jiu-Jitsu is no good here.”<br />

If T-shirts with snappy sayings had been fashionable in 1880, Jigoro<br />

Kano would have stood at the gate of Eishoji temple proudly brandishing<br />

this phrase across his chest. After studying several different styles<br />

of Jiu-Jitsu, Kano took the best parts of each, added his own principles<br />

of throwing and off-balancing, and founded Judo. Within a few years,<br />

he wiped his mats with Jiu-Jitsu pupils and indirectly spawned two<br />

more martial arts that have had a lasting effect on MMA. And that<br />

wasn’t even his day job.<br />

The Kid Can’t Sit Still<br />

A history of Judo is essentially the history of its<br />

founder, Jigoro Kano, and the conditions under which<br />

the art was formed. He was born into a sake-brewing<br />

family during a time of great change in Japan. It was<br />

six years after Admiral Perry’s steamships had entered<br />

Tokyo Bay and proved the futility of the feudal system<br />

to the Japanese people. By the time Kano was eight<br />

years old, his country had endured a revolution that<br />

deposed the ruling Shogunate and reinstated Emperor<br />

Meiji. His formative years were filled with excitement<br />

and a burgeoning curiosity about the world beyond<br />

the seas, which the Shoguns had defiantly guarded<br />

the population against for three centuries. His teenage<br />

years were a tornado of new social and intellectual<br />

changes that fueled his desire to know more—a characteristic<br />

that would define his life.<br />

Despite being a government employee at a time<br />

when the government was crumbling, Kano’s father<br />

wasn’t destitute. He ensured that his kids were well<br />

educated by Neo-Confucian scholars and European<br />

private schools. Thus Jigoro, the youngest of three, wasn’t a stereotypical<br />

street-tough candidate for the title of “pioneer of fighting.”<br />

But bullies are a staple of any society, and since Kano was a<br />

scrawny five-foot-two, and the very definition of a ninety-pound<br />

weakling, he was easy prey. Fortunately, the youngster didn’t take<br />

kindly to playing the role of victim, and he dedicated himself<br />

to learning self-defense despite his father’s protestations (Jiu-Jitsu<br />

was known for developing aggressive youth).<br />

Kano enrolled in college at Tokyo Imperial University, where<br />

he became absorbed in academia. He loved learning and didn’t<br />

limit it to the classroom, especially when it came to the ancient<br />

ways that were dying out so rapidly under a blossoming Japanese<br />

intellectual society that craved everything western. Oddly<br />

enough, Jiu-Jitsu was being maintained at the time by osteopaths<br />

(sometimes called “bonesetters”), so Kano sought out a doctor<br />

who could teach him how to stop getting his ass kicked. Unfortunately,<br />

Kano chose Jiu-Jitsu masters who had a bad habit of dying.<br />

His first instructor, Hachinosuke Fukuda, met an untimely<br />

demise shortly after Kano walked through his door, so you would<br />

think Iso Masatomo would have kept young Kano out. He didn’t,<br />

and died shortly thereafter.<br />

Kano found a new school and discovered that moving around<br />

like an Army brat had its advantages. The constant upheaval from<br />

school to school gave him an opportunity to compare styles and<br />

determine what worked and what didn’t. In the waning days of<br />

the nineteenth century, Jiu-Jitsu was taught in two forms: kata, or<br />

rigid form, and randori, which meant “free form,” similar to what<br />

we would call open mat grappling today. Fukuda’s Tenjin Shinyoryu<br />

style stressed randori over kata, and favored actual practice<br />

over rigid forms. Masatomo’s style stressed free-form grappling as<br />

well, but he was also a master of striking vital areas. Kano’s third<br />

teacher was Iikubo Tsunetoshi, who taught him Kito-ryu Jiu-Jitsu,<br />

as well as the throwing techniques for which Judo would eventually<br />

become renowned. Kano didn’t stop there. When he repeatedly<br />

lost to a larger student in his dojo and needed a way to compensate<br />

for his smaller stature, he added Sumo wrestling moves to<br />

Students of the<br />

Kodokan Judo clan<br />

assemble before<br />

Jigoro Kano.<br />

FIGHTMAGAZINE.COM | JUNE 2009<br />

87

JUDO<br />

his repertoire. It was his open mind and willingness to try whatever<br />

worked that formed the basis of Judo, which was technically<br />

the first mixed martial art. But he wasn’t there just yet.<br />

I Did It My Way<br />

In only four years Kano was licensed to teach Jiu-Jitsu and,<br />

in 1882, at just twenty-two years old, he felt the time had come<br />

to teach on his own. The precocious youth took nine students<br />

and twelve tatami mats to Eishoji Buddhist temple, in Kamakura,<br />

to teach his reformed style of Jiu-Jitsu. Kano focused his teachings<br />

on breaking his opponent’s posture before moving in for<br />

the throw—an unheard-of technique at the time. “The transition<br />

from Jiu-Jitsu to Judo was made slowly but surely,” says author<br />

Andy Adams, “although it is difficult to pinpoint the day when<br />

what that handful of students were learning was no longer Jiu-<br />

Jitsu, but Judo.” Symbolically it was the day he tossed his former<br />

master, Tsunetoshi, around the dojo like a couch pillow during a<br />

randori match.<br />

Two years later, he had his own school, with its own set of bylaws.<br />

Kano would later write, “By taking together all the good<br />

points I had learned of the various schools and adding thereto my<br />

own inventions and discoveries, I devised a new system for physical<br />

culture and moral training. This I call Kodokan Judo.”<br />

Ju means “pliancy” and do means “the way,” which some<br />

have translated as “the gentle way.” Kano’s Judo blended the pinning<br />

and choking techniques of Tenjin Shinyo-ryu Jiu-Jitsu, the<br />

throwing techniques of Kito-ryu, and some Sumo wrestling into<br />

a unique martial art. The revolutionary part of it was kuzushi,<br />

or off-balancing. Judo’s core was to use an opponent’s weight<br />

against him to disrupt his balance and throw him to the ground.<br />

There he would be vulnerable to a pin, choke, or joint lock. Kuzushi<br />

led to an efficiency of effort, and that efficiency led to a<br />

superior technique that enabled a smaller man to defeat a larger<br />

one. Kano found his motto: “The maximum efficiency with min -<br />

imal effort.”<br />

His Judo was taught mostly via randori (free exercise under<br />

contest conditions: throwing, pinning, choking, and joint locks),<br />

although kata (form or prearranged exercises: hitting, kicking,<br />

weapons) was also part of the curriculum. Randori promoted cre -<br />

ativity, free thinking, and free movement. Kata was formulaic,<br />

embodying the Shogun-era view of education as indoctrination,<br />

not the Meiji-era appreciation for discovery. It’s a teaching style,<br />

seen in almost any dojo today, in which an instructor teaches a<br />

move and then allows his students ample time to practice it with<br />

a partner. Judo also embodied the core belief that experience was<br />

more important than strength or power, so an older, wiser judo -<br />

ka (practitioner of Judo) could defeat a stronger, faster student.<br />

But Kano didn’t limit his art to a simple means of self-defense.<br />

He saw in it a way to make people and society better<br />

through the three pillars of Judo: self-defense, physical culture,<br />

and moral behavior. The three were interrelated and inseparable.<br />

“Since the very beginning, I had been categorizing<br />

Judo into three parts,” Kano wrote, “a physical exercise,<br />

a martial art, and the cultivation of wisdom and<br />

virtue. I anticipated that practitioners would develop<br />

their bodies in an ideal manner and also improve their<br />

wisdom and virtue, and make the spirit of Judo live in<br />

their daily lives.”<br />

Chivalry Is Reborn<br />

It’s important to note that Japan in the late nineteenth<br />

century had no concept of sport. It was a society<br />

quickly coming out of three hundred years of isolation<br />

that didn’t understand the meanings of “team” or “fair<br />

play.” Japan was on the other end of the spectrum from<br />

the most powerful nation on the planet—Britain—which<br />

imbued its adolescents with the spirit of competition and<br />

exported its games around the world, including America<br />

(rugby and cricket were the bases for football and baseball).<br />

British youth grew up knowing the meaning of selfless sacrifice,<br />

that the victory of the team is greater than the victory<br />

of the individual. The British saw sport as a part of life that<br />

brought people together peacefully.<br />

Kano believed in the western concept of fair play, and saw the<br />

need for organized sport in everyday life. As the headmaster of the<br />

elite Gakushin School, he mandated that all students participate<br />

in a sport (thus starting the tradition of gym class hazing). Until<br />

that time, the ruling samurai culture believed that the one perfect<br />

cut of a katana blade was all that was needed to end a contest, so<br />

its fighting style was aptly called shobu, or “sudden death.” Kano<br />

saw shobu as stifling creativity because it was risk-averse and detracted<br />

from the student’s ability to formulate a strategy. If a game<br />

had multiple opportunities to score, participants would have to<br />

develop plans of attack and take risks to win, so he organized Judo<br />

contests around point-scoring systems instead of shobu.<br />

1860 – Jigoro Kano<br />

was born.<br />

1871 – Family moved<br />

to Tokyo.<br />

1874 – Sent to private<br />

schools run by Europeans.<br />

1877 – Enrolls at Tokyo<br />

Imperial University.<br />

Starts dabbling in Tenjin<br />

Shinyo-ryu Jiu-Jitsu,<br />

under Hachinosuke<br />

Fukuda.<br />

1879 – Demonstrated<br />

Jiu-Jitsu for Ulysses S.<br />

Grant when he visited<br />

Japan. Fukuda died.<br />

Kano began studying<br />

with Iso Masatomo,<br />

who stressed kata<br />

(form), atemi (striking<br />

vital areas), and randori<br />

(free form).<br />

1881 – Licensed to<br />

teach Tenjin Shinyo-ryu.<br />

Kano saw demo of<br />

Yoshin-ryu by Hirosuke<br />

Totsuka . Masatomo<br />

died. Kato began<br />

training in Kito-ryu<br />

with Iikubo Tsunetoshi<br />

and learned throwing<br />

techniques.<br />

1882 – Became<br />

an instructor at<br />

Gakushuin, an elite<br />

school. Established<br />

Kodokan in a temple;<br />

opened the Kano Juka,<br />

a prep school, and the<br />

Koubunkan, an English<br />

language school.<br />

1883 – Kano established<br />

a dojo at home.<br />

1884 – Judo formally<br />

established, with bylaws.<br />

Red and White<br />

tournament.Rice cake<br />

cutting ceremony.<br />

88 FIGHTMAGAZINE.COM | JUNE 2009

JUDO<br />

1884 was a big year for Judo. Kano had written the first bylaws<br />

of his Kodokan (judo school), instituted the rice cake cutting ceremony<br />

to start his hellish winter training session, and inaugurated<br />

the first Red and White tournament that is now the longest<br />

running competitive sporting event in the world. As Wayne Muromoto<br />

wrote in his magazine, Furyu: The Budo Journal, these early<br />

competitions had rules, but they were still trying to define themselves.<br />

“You scored an ippon (a full point) with throws, chokes,<br />

holds, or arm locks that would, in an actual situation, completely<br />

overwhelm your opponent. You usually went until someone<br />

dropped from sheer exhaustion or the judge ended it, awarding<br />

the match to the clear victor.”<br />

“Kosen students were the green berets of Judo.<br />

They were seen as the cream of the grappling<br />

crop, and their attitude of “I’ll let it snap before I<br />

tap” earned them a great deal of respect”<br />

These achievements, though remarkable, were still known only<br />

among the practitioners of Kodokan Judo. It wasn’t until 1886<br />

that Judo announced its presence with authority to the public by<br />

soundly defeating the powerful Totsuka-ha Yoshin-ryu Jiu-Jitsu<br />

school at a Tokyo Metropolitan Police Academy challenge (final<br />

score 12-2 with two draws, but historical accounts differ ). Suddenly<br />

people took note of the frail Kano and his ability to toss<br />

aside a larger, stronger man effortlessly. The police challenge was<br />

to Judo what the first Stephan Bonnar-Forrest Griffin fight was to<br />

the UFC, and for the next fourteen years, Judo enjoyed a meteoric<br />

rise in popularity.<br />

But at the turn of the century, the art tasted its first bitter pill<br />

of defeat. In 1900, the Kodokan lost a challenge match to the Fusen-ryu<br />

Jiu-Jitsu school, which emphasized newaza, or grappling<br />

techniques, over tachi-waza, or throwing techniques. Kano was<br />

not about to sit around and let his art take a black eye. He sought<br />

out the Fusen-ryu master, Mataemon Tanabe, to learn his repertoire<br />

of grappling techniques, and immediately incorporated<br />

them into the Kodokan’s teachings. This was a milestone because<br />

it started a trend toward grappling Judo, with major ramifications<br />

for the martial arts that can still be seen today.<br />

They Call Me Janus<br />

While Jigoro Kano was obsessive about evolving Judo, it<br />

wasn’t his day job. Kano was first and foremost an educator. In<br />

1901, after nineteen years as the Gakushin School headmaster,<br />

he was appointed as director of the Tokyo Higher Normal School.<br />

Kano made great strides in blending sport into everyday life for his<br />

students, and in 1911 Judo officially became part of the Japanese<br />

school system’s curriculum. His efforts to use sport to foster better<br />

relations were recognized when he was appointed the first Asian<br />

member of the International Olympic Committee. At that time,<br />

the Olympics were not the spectacle of grandeur that they are today<br />

(the 1908 games listed Tug-of-War as a sport), but his appointment<br />

was still another major milestone in the history of Judo.<br />

By 1912, Judo dominated the Japanese martial arts landscape,<br />

and Jiu-Jitsu was in jeopardy of dying out altogether. Kano’s obsession<br />

with learning kicked in and, in order to salvage what he<br />

could from a seemingly doomed art, he pulled together the remaining<br />

authorities on Jiu-Jitsu and adopted their most effective<br />

techniques for the Kodokan. But this had an unforeseen side effect.<br />

Along with a trend toward newaza, which began after the<br />

Fusen-ryu victory, an influx of new ground techniques generated<br />

a highly effective form of grappling Judo, especially at high<br />

school tournaments. It was called Kosen Judo, and the style was<br />

so dominant that, by 1925, Kano’s core tachi-waza throwing<br />

techniques were in danger of becoming extinct.<br />

For the first time in his professional life, Jigoro Kano displayed<br />

a close-minded approach to learning. He changed the rules of<br />

Judo tournaments so that athletes were required to start from a<br />

standing throwing position, so they were forced to learn the core<br />

principles of kuzushi. No matter how close throwing techniques<br />

were to his heart, however, Kano recognized the need for the art<br />

to evolve. Applying a clear double standard, he withdrew his rule<br />

change for a few select schools known as the “Seven Universities.”<br />

To this day, their tournaments are held under different rules from<br />

those of the rest of the Japanese school system ; and it’s in those<br />

tournaments that Kosen Judo still flourishes.<br />

The Judo Virus<br />

Kosen students were the green berets of Judo. They were<br />

seen as the cream of the grappling crop, and their attitude of “I’ll<br />

let it snap before I tap” earned them a great deal of respect in<br />

the sport. It also spawned two Judo offshoots that would become<br />

world renowned: Sambo and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.<br />

Mitsuyo Maeda, long credited with having taught the Gracie<br />

family his fighting style, enrolled in the Kodokan in 1897 and was<br />

trained as a judoka during the golden age of grappling Judo. He<br />

proved himself in multiple tournaments, so in 1904 Kano sent<br />

him on a world “Judo is great” tour that eventually ended in Brazil.<br />

Known as the Conde Coma (“Count of Combat”), Maeda reportedly<br />

won over 1,000 matches on four continents as he challenged<br />

anyone and everyone to a fight. His mix of Judo, Jiu-Jitsu,<br />

and striking, which he’d gleaned from so many fights, formed<br />

the nearly perfect street-fighting technique that he taught in his<br />

new school in Brazil during the 1920s. In 1925, Brazilian politician<br />

Gastão Gracie took notice and hired Maeda to teach his sons<br />

Carlos and Helio. If you don’t know the history of Gracie Jiu-Jitsu<br />

thereafter, grab a copy of my book and read chapter two.<br />

Shortly after World War II, one of the greatest milestones in<br />

Judo history occurred in Brazil. Gracie Jiu-Jitsu enjoyed an explosion<br />

in popularity, and the country was captivated with the family’s<br />

resident bad ass, Helio Gracie, who had proven to be a master<br />

1886 – Challenge at<br />

theTokyo Metropolitan<br />

Police Academy.<br />

1888 - Kano gave a<br />

lecture at the British<br />

embassy in Tokyo:<br />

“Gaining Victory by<br />

Yielding to Strength.”<br />

1890 – Second Kodokan<br />

building.<br />

1889 – Kano took first<br />

trip to spread the word<br />

on Judo.<br />

1892 – Kano made first<br />

trip to Shanghai.<br />

1894 – Third Kodokan<br />

building. First Kodokan<br />

council. First special<br />

winter training session<br />

(kangeiko).<br />

1896 – First special<br />

summer training session<br />

(shochugeiko).<br />

1897 – Fourth Kodokan<br />

building.<br />

1898 – Fifth Kodokan<br />

building. Kano was<br />

appointed Director of<br />

Primary Education at<br />

the Ministry of Education.<br />

1901 – Kano appointed<br />

President of Tokyo<br />

Higher Normal School.<br />

1909 – Kano appointed<br />

to IOC. His Kodokan<br />

became a Japanese<br />

foundation<br />

1911 – Judo teachers<br />

training association<br />

established. Judo<br />

introduced as part of<br />

the school system.<br />

FIGHTMAGAZINE.COM | JUNE 2009<br />

89

JUDO<br />

of fighting. In 1949, the Gracies challenged the best in Judo to a<br />

fight in front of 20,000 Brazilians. The result was the epic battle<br />

between Helio and Masahiko Kimura. In eighteen minutes Helio<br />

was overwhelmed, and his elbow was broken when he refused<br />

to tap under the duress of Kimura’s signature move. (If Kimura<br />

had been Tito Ortiz, he would have immediately put on a “Your<br />

Jiu-Jitsu is no good here” tee-shirt). It would be 34 years before<br />

the Gracie family traveled abroad to stage another challenge,<br />

but when they did, it would be big. They called it “The Ultimate<br />

Fighting Championship.”<br />

On the other side of the world, another Kosen Judo student<br />

was taking his own show on the road, though it’s doubtful he<br />

ran into any spicy Brazilian ladies along the way. Vasili Oshchepkov<br />

was awarded his second dan (grades of Judo black belts; there<br />

are five) from Jigoro Kano himself, and he took his art back to<br />

Russia. There he mixed it with various ethnic styles of wrestling<br />

(Georgian, Moldavian , Uzbek, and Armenian) and developed the<br />

framework of what would eventually become the Soviet art of<br />

Sambo. Along with Victor Spiridonov, Oshchepkov taught it to<br />

the Red Army starting in 1923.<br />

During the Cold War, Soviet Sambo had evolved enough to become<br />

a new form that was distinct from traditional Judo. In typical<br />

Soviet fashion, Sambo practitioners thought themselves to be<br />

superior to Judo fighters. That all changed in 1972, when judokas<br />

Katsuhiko Kashiwazaki and Nobuyuki Sato entered a national<br />

Sambo competition in Riga, Latvia, and destroyed everyone. Suddenly,<br />

Sambo clubs converted back into Judo clubs. Those wacky<br />

Soviets had a habit of overestimating themselves.<br />

Mitsuyo Maeda<br />

(AKA Count Coma)<br />

is the man credited<br />

with teaching the<br />

Gracies.<br />

Modern Judo<br />

Back in Japan, Judo had gained nationwide prominence<br />

when the first all-Japan tournament was held in 1930. But just<br />

when it seemed as if Judo would become the national pastime, Japan<br />

entered one of its darkest periods. The 1930s saw the start of<br />

a bloody phase of violent Japanese expansionism that didn’t end<br />

until atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in<br />

1945. During this time, with most of the country’s fighting-age<br />

men deployed around East Asia, Judo stagnated. It suffered an additional<br />

blow in 1938, when Jigoro Kano died on a ship while en<br />

route back to Japan from an IOC meeting in Cairo.<br />

Under the U.S. occupation after World War II, Japan experienced<br />

a period of nonaggression that reinvigorated the art and<br />

even spread it back to North America. In 1951 the International<br />

Judo Federation was formed and, just five years later, it held its first<br />

World Championships in Tokyo. The IJF opted not to restrict the<br />

competition to weight classes since the philosophy of Judo was<br />

that a smaller man could easily throw a larger one. That theory<br />

was literally tossed out the window at the third world championships,<br />

in 1961, when Dutch judoka Anton Geesink won the world<br />

title. The domination of Judo by a non-Japanese was a shocking<br />

revelation, and it changed the sport. Reluctantly, the IJF instituted<br />

weight classes, but this bad tiding produced good news. The<br />

installment of weight classes meant that the competition was getting<br />

better. Judokas around the world were becoming more and<br />

more skilled at their art, so the division of competitors into classes<br />

based on weight evened out the playing field to compensate for<br />

their prowess. In 1964, Men’s Judo was introduced in the Olympic<br />

Games, and it became a permanent sport in 1972. In 1988, the<br />

open weight class was dropped from Judo Olympic competition,<br />

and in 1992 Women’s Judo became an Olympic sport.<br />

Judo’s influence on Mixed Martial Arts is evident. Several judokas<br />

are successful in MMA, including Pride FC and UFC vet<br />

Rameau Thierry Sokoudjou, who won the US Open Judo championship<br />

in 2001. One of the greatest fighters of all time, Fedor<br />

Emelianenko, comes from a Sambo fighting background. And in<br />

a moment of history repeating itself, Renzo Gracie refused to tap<br />

when caught in a Kimura lock by Kazushi Sakuraba at Pride 10,<br />

resulting in a badly broken elbow.<br />

“Judo almost gives you an unfair advantage in a fight,” says<br />

UFC welterweight Karo Parisyan. “If a guy comes at me like a<br />

beast or tries to get my back, I just use his strength and aggression<br />

against him and dump him on his head.”<br />

Karo needs to wear a printed t-shirt after a win:<br />

“Your Jiu-Jitsu is no good here.”<br />

1920 – Kano left Tokyo<br />

Higher Normal School.<br />

1930 – First All-Japan<br />

Judo tournament.<br />

1938 – Kano died.<br />

1949 – Helio Gracie vs.<br />

Masahiko Kimura fight.<br />

1951 – IJF formed.<br />

1956 – World Judo<br />

Championships in<br />

Tokyo.<br />

1958 – New Kodokan<br />

built.<br />

1961 – Anton Geesink<br />

of Holland won the<br />

world championship.<br />

Weight classes<br />

instituted.<br />

1964 – Men’s Judo<br />

introduced to Olympic<br />

Games.<br />

1972 – Judo became<br />

permanent sport in the<br />

Olympics. Japanese<br />

judokas went to the<br />

Soviet Union and kicked<br />

their asses.<br />

1988 – Open weight<br />

class dropped from<br />

Judo Olympic competition.<br />

1992 – Women’s Judo<br />

became an Olympic<br />

sport.<br />

90 FIGHTMAGAZINE.COM | JUNE 2009