Burgundy Black Truffle Cultivation in an Agroforestry Practice

Burgundy Black Truffle Cultivation in an Agroforestry Practice

Burgundy Black Truffle Cultivation in an Agroforestry Practice

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

AGROFORESTRY IN ACTION<br />

University of Missouri Center for <strong>Agroforestry</strong><br />

AF1015 - 2011<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> <strong>Black</strong> <strong>Truffle</strong> <strong>Cultivation</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>Agroforestry</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

by Joh<strong>an</strong>n Bruhn, Ph.D., Research Associate Professor, Division<br />

of Pl<strong>an</strong>t Sciences, University of Missouri, & Michelle Hall, Senior<br />

Information Specialist, The Center for <strong>Agroforestry</strong>, University of<br />

Missouri<br />

The two best c<strong>an</strong>didate species for truffle<br />

cultivation <strong>in</strong> the south-central U.S. are the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle (Tuber aestivum Vitt., syn. T.<br />

unc<strong>in</strong>atum Ch., Fig. 1a) <strong>an</strong>d the Périgord black truffle<br />

(T. mel<strong>an</strong>osporum Vitt., Fig. 1b). These common names<br />

(<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle <strong>an</strong>d Périgord black truffle) are<br />

derived from the names of two of the m<strong>an</strong>y regions<br />

<strong>in</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>ce where they are famous. Though native<br />

to Europe, there is great <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> exp<strong>an</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

cultivated r<strong>an</strong>ge of both of these species.<br />

Each of these two truffle species has unique life cycle<br />

features <strong>an</strong>d characteristic habitat requirements.<br />

Although the retail price of Périgord black truffles<br />

is roughly twice that of <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffles, Périgord<br />

truffles mature dur<strong>in</strong>g the w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>an</strong>d are destroyed<br />

if they thaw <strong>in</strong> the ground after hav<strong>in</strong>g frozen solid.<br />

In contrast, <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffles mature ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> late<br />

autumn, before d<strong>an</strong>ger of the soil freez<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

In addition, the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus c<strong>an</strong> produce<br />

higher yields per acre, perhaps because it typically<br />

grows <strong>in</strong> the shade of denser st<strong>an</strong>ds of trees. Denser<br />

st<strong>an</strong>ds of trees also serve to more effectively filter <strong>an</strong>d<br />

cle<strong>an</strong>se groundwater (for example, Allen et al. 2004).<br />

The recently discovered nitrogen fixation activities<br />

of truffles (see “The <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle as a<br />

ectomycorhizal fungus,” below) places them <strong>in</strong><br />

the comp<strong>an</strong>y of legume nodules as agents of soil<br />

improvement (Barbieri et al. 2010).<br />

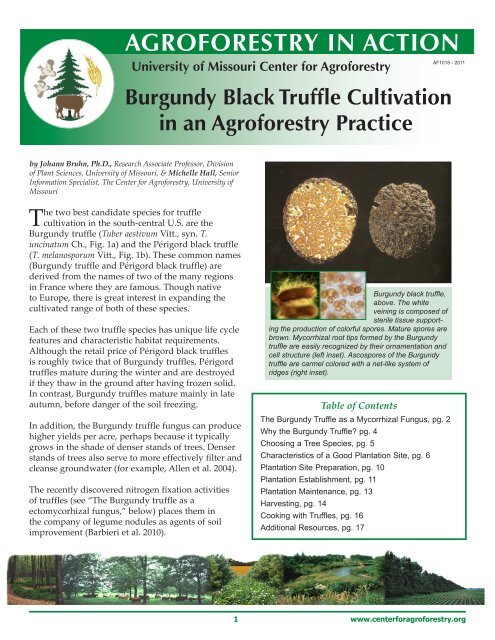

<strong>Burgundy</strong> black truffle,<br />

above. The white<br />

ve<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is composed of<br />

sterile tissue support<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the production of colorful spores. Mature spores are<br />

brown. Mycorrhizal root tips formed by the <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle are easily recognized by their ornamentation <strong>an</strong>d<br />

cell structure (left <strong>in</strong>set). Ascospores of the <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle are carmel colored with a net-like system of<br />

ridges (right <strong>in</strong>set).<br />

Table of Contents<br />

The <strong>Burgundy</strong> <strong>Truffle</strong> as a Mycorrhizal Fungus, pg. 2<br />

Why the <strong>Burgundy</strong> <strong>Truffle</strong>? pg. 4<br />

Choos<strong>in</strong>g a Tree Species, pg. 5<br />

Characteristics of a Good Pl<strong>an</strong>tation Site, pg. 6<br />

Pl<strong>an</strong>tation Site Preparation, pg. 10<br />

Pl<strong>an</strong>tation Establishment, pg. 11<br />

Pl<strong>an</strong>tation Ma<strong>in</strong>ten<strong>an</strong>ce, pg. 13<br />

Harvest<strong>in</strong>g, pg. 14<br />

Cook<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>Truffle</strong>s, pg. 16<br />

Additional Resources, pg. 17<br />

1<br />

www.centerforagroforestry.org

This stra<strong>in</strong> of Bradyrhizobium is one of<br />

m<strong>an</strong>y that we have isolated <strong>in</strong>to pure<br />

culture from with<strong>in</strong> <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffles.<br />

Bradyrhizobium species fix atmospheric<br />

nitrogen <strong>in</strong> legume nodules, but are also<br />

believed to fix nitrogen <strong>in</strong>side develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

truffles. As a result, <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

cultivation may improve soil quality <strong>in</strong> a<br />

m<strong>an</strong>ner similar to legume cultivation.<br />

The <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus also appears to grow<br />

<strong>an</strong>d fruit more competitively over a wider r<strong>an</strong>ge<br />

of soil conditions th<strong>an</strong> the Périgord truffle fungus.<br />

Where appropriate conditions persist, the <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle fungus appears capable of susta<strong>in</strong>ed fruit<strong>in</strong>g<br />

over centuries (Weden et al. 2004b).<br />

Signific<strong>an</strong>tly, most of what we know about the<br />

biology <strong>an</strong>d cultivation of Europe<strong>an</strong> black truffles<br />

is based on research <strong>an</strong>d experience <strong>in</strong> their native<br />

r<strong>an</strong>ges <strong>in</strong> Europe, <strong>an</strong>d much of the scientific literature<br />

concern<strong>in</strong>g the biology <strong>an</strong>d cultivation of the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle has been published <strong>in</strong> Europe<strong>an</strong><br />

l<strong>an</strong>guages (for example, Chevalier <strong>an</strong>d Frochet 1997,<br />

Olivier et al. 2002, Wedén 2008). Nevertheless, work<br />

<strong>in</strong> New Zeal<strong>an</strong>d (Hall et al. 2007) has demonstrated<br />

that the Périgord black truffle c<strong>an</strong> be successfully<br />

cultivated across a wider r<strong>an</strong>ge of soil conditions<br />

th<strong>an</strong> constitute its native Europe<strong>an</strong> r<strong>an</strong>ge, <strong>an</strong>d this<br />

may prove true for the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle as well.<br />

English l<strong>an</strong>guage reports of research <strong>in</strong>to the biology,<br />

ecology <strong>an</strong>d cultivation of the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle (for<br />

example, Delmas 1978; Chevalier et al. 2001; Weden<br />

et al. 2004a, 2004b <strong>an</strong>d 2009; Zambonelli et al. 2005;<br />

Hall et al 2007; Pruett et al. 2008a, 2008b, 2009; Bruhn<br />

et al. 2009; Wehrlen 2008, 2009; Wehrlen et al. 2009)<br />

have helped support research globally. In the face<br />

of limited research support, the spirit of collegiality<br />

among scientists around the world reflects the<br />

universal desire to jo<strong>in</strong>tly adv<strong>an</strong>ce these topics as<br />

quickly as possible.<br />

Despite all that is known about truffle biology<br />

<strong>an</strong>d cultivation, efforts to cultivate these exquisite<br />

mushrooms meet with variable success, often for<br />

reasons not yet understood. We might conclude that<br />

successful trufficulture today is largely based on<br />

science, with signific<strong>an</strong>t room for <strong>in</strong>spiration <strong>an</strong>d<br />

luck.<br />

For all of these reasons, the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

appears better suited th<strong>an</strong> the Périgord black<br />

truffle as a susta<strong>in</strong>able agroforestry specialty crop<br />

under Missouri conditions. The <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

is probably the most widely eaten truffle species <strong>in</strong><br />

Europe (Riousset et al. 2001). The biology, ecology,<br />

cultivation <strong>an</strong>d use of the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle are the<br />

subjects of this publication.<br />

Before discuss<strong>in</strong>g cultivation of the <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle, we need to underst<strong>an</strong>d (to the best of<br />

current knowledge) the biology <strong>an</strong>d ecology of this<br />

remarkable fungus.<br />

<strong>Truffle</strong> cultivation is a perplex<strong>in</strong>g endeavor<br />

for several key reasons, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

1) the complex mycorrhizal nature of truffle fungi;<br />

2) the long period between truffle orchard<br />

establishment <strong>an</strong>d truffle fruit<strong>in</strong>g; <strong>an</strong>d<br />

3) the fact that <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle “mushrooms”<br />

typically form submerged <strong>in</strong> the soil.<br />

The <strong>Burgundy</strong> <strong>Truffle</strong> as a<br />

Mycorrhizal Fungus<br />

<strong>Truffle</strong> fungi depend for their existence on the<br />

successful establishment of a mutually beneficial<br />

nutritional relationship with the root systems<br />

of receptive tree species (so-called “host” trees).<br />

This sort of mutualistic symbiosis between rootcoloniz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

truffle fungi <strong>an</strong>d receptive tree species<br />

is representative of one form of “mycorrhizal”<br />

relationship.<br />

The word mycorrhiza (plural, mycorrhizas;<br />

adjective, mycorrhizal) comes from two Greek<br />

words that tr<strong>an</strong>slate roughly as “fungus root.”<br />

In simplest terms, a truffle fungus modifies root<br />

tip <strong>an</strong>atomy of receptive pl<strong>an</strong>ts to facilitate the<br />

exch<strong>an</strong>ge of sugar produced by the pl<strong>an</strong>t (through<br />

photosynthesis) for m<strong>in</strong>erals <strong>an</strong>d water gathered by<br />

the fungus from the soil. Nearly all l<strong>an</strong>d pl<strong>an</strong>t species<br />

require some form of mycorrhizal relationship to<br />

survive (Smith <strong>an</strong>d Read 1997). Due to its f<strong>in</strong>ely<br />

br<strong>an</strong>ched structure, the fungal weft, compris<strong>in</strong>g<br />

myriad microscopic filaments, is able to forage<br />

among soil particles far more efficiently th<strong>an</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>e<br />

roots of the pl<strong>an</strong>t alone.<br />

The Center for <strong>Agroforestry</strong> at the University of Missouri<br />

2

Most tree species associate with fungi that<br />

produce either “ectomycorrhizas” or “arbuscular<br />

mycorrhizas.” The fungi that produce ecto- vs.<br />

arbuscular mycorrhizas are quite unrelated. <strong>Truffle</strong><br />

fungi produce ectomycorrhizas. “Ecto” is the Greek<br />

prefix me<strong>an</strong><strong>in</strong>g “outside,” referr<strong>in</strong>g to the fact that<br />

ectomycorrhizal fungi affect the outward appear<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

of colonized root tips. “Arbuscular” is the Greek<br />

adjective me<strong>an</strong><strong>in</strong>g “tree-shaped,” referr<strong>in</strong>g to the<br />

tree-shaped “arbuscules” produced by the fungus<br />

with<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>e root cortex cells. Arbuscular fungi do not<br />

noticeably modify root tip appear<strong>an</strong>ce. It’s import<strong>an</strong>t<br />

to know what k<strong>in</strong>d of mycorrhizas different tree<br />

species form because arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi<br />

won’t replace <strong>an</strong> ectomycorrhizal fungus. Thus,<br />

truffle-colonized (ectomycorrhizal) oak seedl<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

c<strong>an</strong> be <strong>in</strong>terpl<strong>an</strong>ted among (arbuscular mycorrhizal)<br />

apple trees to take adv<strong>an</strong>tage of the shade provided<br />

by the apple trees. Table 1 provides lists of some<br />

common ectomycorrhizal <strong>an</strong>d arbuscular mycorrhizal<br />

tree species.<br />

Fortunately, the ectomycorrhizas produced by the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus are quite dist<strong>in</strong>ctive <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>an</strong><br />

generally be discerned under the dissect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d/or<br />

compound microscope from those produced by other<br />

ectomycorrhizal fungi (Müller et al. 1996; Chevalier<br />

<strong>an</strong>d Frochot 1997). Nevertheless, nurserymen,<br />

consult<strong>an</strong>ts <strong>an</strong>d pl<strong>an</strong>tation owners alike should<br />

have the mycorrhizal condition of their greenhouse<br />

seedl<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>an</strong>d pl<strong>an</strong>tation trees evaluated by <strong>an</strong><br />

impartial laboratory. These confirmations should<br />

consist at least of a systematic microscopic evaluation.<br />

Ideally, this evaluation should be accomp<strong>an</strong>ied by<br />

extraction <strong>an</strong>d identification of fungal DNA from<br />

samples of tentatively identified truffle mycorrhizas<br />

(for example, Iotti <strong>an</strong>d Zambonelli 2006). This process<br />

is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly affordable, <strong>an</strong>d provides import<strong>an</strong>t<br />

assur<strong>an</strong>ces to all parties <strong>in</strong>volved at every stage of<br />

truffle cultivation.<br />

Systems for the <strong>in</strong>dependent certification of<br />

greenhouse seedl<strong>in</strong>g colonization are widely<br />

used <strong>in</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>ce (Chevalier <strong>an</strong>d Grente 1978), Italy<br />

(Bencivenga et al. 1995), <strong>an</strong>d Spa<strong>in</strong> (Fischer <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Col<strong>in</strong>as 1996). Seedl<strong>in</strong>gs from greenhouse production<br />

batches that have been certified to be well colonized<br />

by the <strong>in</strong>tended truffle species are sold bear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

tags affirm<strong>in</strong>g their certification <strong>an</strong>d identify<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the certify<strong>in</strong>g agency. Systematic <strong>in</strong>dependent<br />

certification has yet to be established elsewhere.<br />

Caveat emptor… Let the buyer beware!<br />

Table 1. Some tree species known to associate with arbuscular<br />

mycorrhizal fungi <strong>an</strong>d/or ectomycorrhizal fungi.<br />

Common name Scientific Arbusc. Ecto.<br />

name<br />

Apple<br />

Ash<br />

Aspen, cottonwood,<br />

poplar*<br />

Bamboo<br />

Beech<br />

<strong>Black</strong> locust<br />

Box elder<br />

Buckeye,<br />

horse chestnut<br />

Catalpa<br />

Cherry, peach,<br />

plum*<br />

Chestnut<br />

Dogwood<br />

G<strong>in</strong>kgo<br />

Grape<br />

Hackberry<br />

Hazelnut<br />

Hickory, pec<strong>an</strong><br />

Holly<br />

Hornbeam<br />

Juniper<br />

L<strong>in</strong>den<br />

Magnolia<br />

Maple<br />

Mulberry<br />

Oak<br />

Persimmon<br />

P<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Redbud<br />

Tulip<br />

Viburnum<br />

Walnut<br />

Willow*<br />

Malus<br />

Frax<strong>in</strong>us<br />

Populus<br />

Bamusa<br />

Fagus<br />

Rob<strong>in</strong>ia<br />

Acer negundo<br />

Aesculus<br />

Catalpa<br />

Prunus<br />

Cast<strong>an</strong>ea<br />

Cornus<br />

G<strong>in</strong>kgo<br />

Vitis<br />

Celtis<br />

Corylus<br />

Carya<br />

Ilex<br />

Carp<strong>in</strong>us<br />

Juniperus<br />

Tilia<br />

Magnolia<br />

Acer<br />

Morus<br />

Quercus<br />

Diospyros<br />

P<strong>in</strong>us<br />

Cercis<br />

Liriodendron<br />

Viburnum<br />

Jugl<strong>an</strong>s<br />

Salix<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

E<br />

3<br />

www.centerforagroforestry.org

An Agritruffe oak<br />

seedl<strong>in</strong>g certified by<br />

the French INRA to<br />

be colonized by the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle.<br />

(Inset) Examples of<br />

French <strong>an</strong>d Sp<strong>an</strong>ish<br />

tags used to label<br />

seedl<strong>in</strong>gs certified to<br />

be colonized by truffle<br />

fungi.<br />

To make th<strong>in</strong>gs more “<strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g,” it is clear now<br />

that mycorrhizal fungi (truffle fungi <strong>in</strong>cluded)<br />

associate with a wide variety of bacteria that<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence mycorrhiza formation <strong>an</strong>d function (for<br />

example, Frey-Klett et al. 2007, Bonf<strong>an</strong>te <strong>an</strong>d Anca<br />

2009). Quite recently, it has been shown that truffle<br />

fruit bodies also host large <strong>an</strong>d diverse bacterial<br />

communities (Barbieri et al. 2005, 2007), that <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

nitrogen-fix<strong>in</strong>g bacteria (Cerig<strong>in</strong>i et al. 2008, Barbieri<br />

et al. 2010) closely related to those that nodulate the<br />

root systems of legumes. The roles of bacteria present<br />

<strong>in</strong> large numbers <strong>in</strong> <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle mycorrhizas<br />

<strong>an</strong>d fruit-bodies are the subject of ongo<strong>in</strong>g research<br />

(Bruhn, Emerich, Wedén, <strong>an</strong>d Backlund, <strong>in</strong><br />

preparation).<br />

The <strong>in</strong>troduction of selected bacterial stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>to<br />

truffle seedl<strong>in</strong>g production systems is <strong>an</strong> excit<strong>in</strong>g<br />

prospect (for example, Thrall et al. 2005). One of<br />

the difficulties <strong>in</strong> resolv<strong>in</strong>g the requirements for<br />

truffle cultivation is the potential disconnect between<br />

the successful establishment of a mycorrhizal root<br />

system <strong>an</strong>d its subsequent production of truffle<br />

mushrooms. In other words, a successful mycorrhizal<br />

relationship is essential to successful fruit<strong>in</strong>g but<br />

may not guar<strong>an</strong>tee it. It rema<strong>in</strong>s to be determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

how similar are the bacterial communities associated<br />

with mycorrhiza formation <strong>an</strong>d function, <strong>an</strong>d truffle<br />

mushroom <strong>in</strong>itiation <strong>an</strong>d development.<br />

<strong>Truffle</strong> life cycles comprise two<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent phases:<br />

1) The nutritional relationship between the truffle<br />

fungus, its partner tree, <strong>an</strong>d associated microbes; <strong>an</strong>d<br />

2) The sexual reproduction of the fungus <strong>in</strong> the form<br />

of truffle mushrooms.<br />

This issue is difficult to study because <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle production commonly lags pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

mycorrhizal tree seedl<strong>in</strong>gs by six to 10 years<br />

(Chevalier et al. 2001, Wedén et al. 2009). Full<br />

production may be reached by orchard age 12-15<br />

years, <strong>an</strong>d is commonly associated with the<br />

establishment of shade <strong>an</strong>d a litter layer.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, when (<strong>an</strong>d if) <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffles do develop<br />

<strong>in</strong> a pl<strong>an</strong>tation, they generally form completely below<br />

the soil surface. As a result, effective harvest <strong>an</strong>d<br />

evaluation of production requires the services of a<br />

well-tra<strong>in</strong>ed dog to f<strong>in</strong>d them as they mature.<br />

So, to summarize, if you do everyth<strong>in</strong>g right<br />

(<strong>in</strong>tentionally <strong>an</strong>d with some good luck), your truffle<br />

orchard will eventually yield tens of pounds of<br />

truffles per acre for years, but if you make <strong>an</strong>y error<br />

you won’t even know it for 10 years, but you will<br />

have a very pleas<strong>an</strong>t st<strong>an</strong>d of lovely trees ! This guide<br />

is designed to provide a general knowledge of truffle<br />

biology <strong>an</strong>d the state-of-the-art of <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

cultivation. We have taken care to draw attention to<br />

the limits of our underst<strong>an</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g, so that the potential<br />

trufficulteur (truffle grower) c<strong>an</strong> bal<strong>an</strong>ce the potential<br />

for success with the risks of failure, based on current<br />

knowledge <strong>an</strong>d its apparent gaps.<br />

Why the <strong>Burgundy</strong> <strong>Truffle</strong>?<br />

The success of a truffle cultivation effort depends on<br />

the match<strong>in</strong>g of a truffle species with a receptive tree<br />

species on a mutually conducive site. Although the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Périgord black truffle species share<br />

common features, they differ markedly <strong>in</strong> a number<br />

of import<strong>an</strong>t ways that <strong>in</strong>fluence their productivity<br />

under m<strong>an</strong>agement.<br />

First, the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle matures ma<strong>in</strong>ly from<br />

September through J<strong>an</strong>uary <strong>in</strong> <strong>Burgundy</strong>, Fr<strong>an</strong>ce,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d from late August through early December on<br />

Gotl<strong>an</strong>d, Sweden (Chevalier <strong>an</strong>d Frochot 1997, Wedén<br />

et al. 2004b). In contrast, the Périgord truffle fruits<br />

The Center for <strong>Agroforestry</strong> at the University of Missouri<br />

4

dur<strong>in</strong>g the w<strong>in</strong>ter, matur<strong>in</strong>g between early December<br />

<strong>an</strong>d mid-March <strong>in</strong> Europe (Olivier et al. 2002). This<br />

difference is supremely import<strong>an</strong>t, because when<br />

truffles freeze <strong>in</strong> the ground, they rot upon thaw<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>an</strong>d are unmarketable (Riousset et al. 2001, Chevalier<br />

<strong>an</strong>d Frochot 1997). Thus, the Périgord black truffle<br />

is poorly suited to locations where the soil rout<strong>in</strong>ely<br />

freezes solid for more th<strong>an</strong> a couple of days at a time<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g w<strong>in</strong>ter. For this reason, we recommend the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle for cultivation throughout Missouri.<br />

Second, <strong>in</strong> locations where the soil does not<br />

characteristically freeze dur<strong>in</strong>g the w<strong>in</strong>ter, the choice<br />

of Périgord or <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle is more a matter<br />

of economics <strong>an</strong>d preference. With its stronger<br />

fragr<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>an</strong>d flavor, top-quality Périgord black<br />

truffles have sold <strong>in</strong> recent years for approximately<br />

$900/lb. <strong>in</strong> the U.S., roughly twice the price of<br />

the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle. Both species of truffle are<br />

approximately twice as expensive <strong>in</strong> the U.S. as <strong>in</strong><br />

Europe, due to their greater availability <strong>in</strong> Europe.<br />

Most Périgord black <strong>an</strong>d <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffles currently<br />

sold <strong>in</strong> the U.S. are imported from Europe, with some<br />

very notable exceptions (http://www.tennesseetruffle.<br />

com/). Price also varies subst<strong>an</strong>tially with <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

truffle size <strong>an</strong>d quality. In these early times, both<br />

Périgord black <strong>an</strong>d <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffles are <strong>in</strong> great<br />

dem<strong>an</strong>d at exclusive restaur<strong>an</strong>ts engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

haute cuis<strong>in</strong>e. Knowledgeable Missouri<strong>an</strong>s appear<br />

more will<strong>in</strong>g to experiment with the purchase of a<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle, due to the price differential.<br />

Third, yields of the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle c<strong>an</strong> be greater<br />

th<strong>an</strong> those of the Périgord truffle, <strong>in</strong> part due to<br />

the greater pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g density recommended for<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle orchards (see “Pl<strong>an</strong>t Density”,<br />

under “Orchard Establishment”, below). Further,<br />

the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus is generally considered<br />

to be more aggressive th<strong>an</strong> the Périgord truffle <strong>in</strong><br />

compet<strong>in</strong>g with coexist<strong>in</strong>g native mycorrhizal fungi,<br />

so pl<strong>an</strong>tations established with the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

c<strong>an</strong> have a longer productive life. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the greater<br />

tree density <strong>in</strong> <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle orchards creates a<br />

much more forested environment, which may be seen<br />

as a value <strong>in</strong> itself, improv<strong>in</strong>g groundwater filtration,<br />

wildlife habitat, <strong>an</strong>d nitrogen fixation associated with<br />

the truffle fungus.<br />

Choos<strong>in</strong>g a Tree Species<br />

The <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus is capable of associat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

with a wide r<strong>an</strong>ge of tree species, but experience<br />

shows that truffle production is greater <strong>in</strong> partnership<br />

Table 2. A list of tree species known to associate with the <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle (Chevalier et al. 2001).<br />

Tree species<br />

Carp<strong>in</strong>us betulus<br />

Cedrus atl<strong>an</strong>tica<br />

Corylus avell<strong>an</strong>a<br />

C. colurna<br />

Ostrya carp<strong>in</strong>ifolia<br />

Q. petraea<br />

Q. pubescens<br />

Q. robur<br />

P<strong>in</strong>us nigra ssp. austriaca<br />

Common name<br />

Europe<strong>an</strong> hornbeam<br />

cedar<br />

common hazelnut<br />

Turkish hazelnut<br />

hop hornbeam<br />

sessile oak<br />

pubescent oak<br />

common oak<br />

Austri<strong>an</strong> black p<strong>in</strong>e<br />

with some tree species th<strong>an</strong> with others. Table 2<br />

presents a list of tree species known to associate<br />

well with the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle (Chevalier et al.<br />

2001). First, <strong>an</strong> appropriate tree species needs to be<br />

receptive to f<strong>in</strong>e-root colonization by the <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle fungus both <strong>in</strong> the greenhouse <strong>an</strong>d at the<br />

pl<strong>an</strong>tation site. So, it also seems import<strong>an</strong>t to use a<br />

tree species that is preferentially colonized by the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus after outpl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the field.<br />

For example, the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle is very productive<br />

with the Europe<strong>an</strong> hazelnut (Corylus avell<strong>an</strong>a L.),<br />

yet C. avell<strong>an</strong>a seems to be quite receptive to a wide<br />

variety of compet<strong>in</strong>g ectomycorrhizal fungi as well.<br />

It is also import<strong>an</strong>t to select a tree species that will<br />

grow well under exist<strong>in</strong>g climate <strong>an</strong>d soil conditions<br />

at the pl<strong>an</strong>tation site. For example, the common oak<br />

(Quercus robur L.) is one of the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal tree species<br />

(along with C. avell<strong>an</strong>a) associated with the <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle on Gotl<strong>an</strong>d. Yet seed sources (proven<strong>an</strong>ces)<br />

of Q. robur vary <strong>in</strong> their cold hard<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>an</strong>d <strong>in</strong> their<br />

toler<strong>an</strong>ce of the high soil pH levels required (above<br />

7.0). These environmental sensitivities need to be<br />

considered when select<strong>in</strong>g seed sources.<br />

It’s tempt<strong>in</strong>g to w<strong>an</strong>t to select a proven tree species<br />

from the native r<strong>an</strong>ge of the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle, but<br />

native North Americ<strong>an</strong> tree species should not<br />

be automatically ruled out. For example, native<br />

tree species resist<strong>an</strong>t to local diseases <strong>an</strong>d pests<br />

may prove to be good <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle associates<br />

compared to related native Europe<strong>an</strong> species.<br />

Examples of diseases which require consideration<br />

<strong>in</strong> the U.S. <strong>in</strong>clude: northern filbert blight (caused<br />

by the fungus Anisogramma <strong>an</strong>omala), which c<strong>an</strong> be<br />

especially severe on Europe<strong>an</strong> hazelnut; chestnut<br />

5<br />

www.centerforagroforestry.org

light (caused by the fungus Endothia parasitica)<br />

on oaks <strong>an</strong>d ch<strong>in</strong>quap<strong>in</strong>; <strong>an</strong>d powdery mildew of<br />

common oak (caused by several fungi, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Microsphaera alphitoides). For example, we have found<br />

that the hybrid Q. robur x Q. bicolor Willd. is resist<strong>an</strong>t<br />

to powdery mildew, while rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g receptive to the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle.<br />

A Quercus robur seedl<strong>in</strong>g display<strong>in</strong>g a high level of powdery<br />

mildew on its foliage. Wire mesh is commonly used<br />

to protect young seedl<strong>in</strong>gs from rabbit damage.<br />

With these <strong>in</strong>sights, we c<strong>an</strong> proceed to consider<br />

the characteristics of a favorable <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

orchard site, site preparation, the establishment <strong>an</strong>d<br />

m<strong>an</strong>agement of the truffière, <strong>an</strong>d the eventual harvest<br />

<strong>an</strong>d utilization of the truffles produced!<br />

Characteristics of a Good<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> <strong>Truffle</strong> Pl<strong>an</strong>tation Site<br />

The suitability of a site for <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

cultivation depends on several <strong>in</strong>ter-related <strong>an</strong>d<br />

equally import<strong>an</strong>t categories of factors: climate <strong>an</strong>d<br />

position <strong>in</strong> the l<strong>an</strong>dscape; l<strong>an</strong>d-use history; soil<br />

properties; <strong>an</strong>d access to water.<br />

Climate <strong>an</strong>d Position <strong>in</strong> the L<strong>an</strong>dscape<br />

Analyses of climatic conditions conducive to<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fruit<strong>in</strong>g have naturally focused on<br />

relationships between truffle harvests <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>nual<br />

patterns of air temperature <strong>an</strong>d precipitation with<strong>in</strong><br />

the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle’s native Europe<strong>an</strong> geographic<br />

r<strong>an</strong>ge (Table 3). Precipitation dur<strong>in</strong>g the period<br />

June through September, as well as total <strong>an</strong>nual<br />

precipitation, seems to be well correlated with <strong>an</strong>nual<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle harvests <strong>in</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>ce (Chevalier <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Table 3. Me<strong>an</strong> precipitation <strong>an</strong>d temperature for Cruzy, <strong>Burgundy</strong>, <strong>in</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>ce, <strong>an</strong>d on the Swedish isl<strong>an</strong>d of Gotl<strong>an</strong>d (Wedén et al.,<br />

2004b). Data for Missouri represent <strong>an</strong> orchard pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g with established <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle mycorrhizae.<br />

Monthly me<strong>an</strong><br />

precipitation (mm)<br />

Monthly me<strong>an</strong><br />

temperature (C)<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong> season for f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g mature<br />

Tuber aestivum a fruit<strong>in</strong>g<br />

bodies (exceptions exist)<br />

Month Gotl<strong>an</strong>d <strong>Burgundy</strong> Missouri Gotl<strong>an</strong>d <strong>Burgundy</strong> Missouri Gotl<strong>an</strong>d <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

J<strong>an</strong>uary<br />

February<br />

March<br />

April<br />

May<br />

June<br />

July<br />

August<br />

September<br />

October<br />

November<br />

December<br />

43.3<br />

32.6<br />

34.6<br />

29.3<br />

28.0<br />

39.5<br />

51.6<br />

48.5<br />

56.8<br />

50.5<br />

57.5<br />

55.5<br />

73.6<br />

69.3<br />

69.3<br />

60.4<br />

81.9<br />

75.9<br />

65.4<br />

66.4<br />

72.0<br />

80.0<br />

83.2<br />

87.1<br />

65.4<br />

54.0<br />

58.0<br />

75.1<br />

131.6<br />

136.7<br />

98.8<br />

108.6<br />

60.9<br />

69.4<br />

56.2<br />

32.0<br />

-1.1<br />

-1.8<br />

0.1<br />

4.0<br />

9.6<br />

14.3<br />

16.3<br />

15.9<br />

12.1<br />

8.1<br />

3.9<br />

0.7<br />

2.7<br />

3.6<br />

6.5<br />

9.0<br />

13.2<br />

16.0<br />

18.7<br />

18.6<br />

15.1<br />

10.9<br />

5.9<br />

3.8<br />

-0.2<br />

0.9<br />

7.7<br />

14.5<br />

18.7<br />

23.2<br />

26.3<br />

25.8<br />

20.0<br />

13.4<br />

7.3<br />

1.2<br />

///////<br />

//////////////<br />

//////////////<br />

//////////////<br />

///////////////<br />

///////<br />

//////////////<br />

//////////////<br />

//////////////<br />

a<br />

French values are recalculated from m.e./100 g to %<br />

The Center for <strong>Agroforestry</strong> at the University of Missouri<br />

6

Frochot 1997, Chevalier et al. 2001). Chevalier et al.<br />

(2001) estimate optimal monthly grow<strong>in</strong>g season<br />

precipitation <strong>in</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>ce to be: April, 20-50 mm (0.8-2<br />

<strong>in</strong>); May, 60-80 mm (2.4-3.1 <strong>in</strong>); June, 60-80 mm (2.4-<br />

3.1 <strong>in</strong>); July, 50-100 mm (2-3.9 <strong>in</strong>); August, 60-80 mm<br />

(2.4-3.1 <strong>in</strong>); <strong>an</strong>d September, 40-60 mm (1.6-2.4 <strong>in</strong>).<br />

In fact, greater precipitation dur<strong>in</strong>g June through<br />

September seems to favor fruit<strong>in</strong>g. As a case <strong>in</strong><br />

po<strong>in</strong>t, heavy precipitation <strong>in</strong> July 2010 resulted <strong>in</strong><br />

strong late-season fruit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Lorra<strong>in</strong>e (personal<br />

communication, Dr. Christophe Rob<strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Mr.<br />

Je<strong>an</strong>-Sébasti<strong>an</strong> Pousse). No comparable relationship<br />

to productivity is yet available for Gotl<strong>an</strong>d, where<br />

average May, June <strong>an</strong>d August precipitation is lower<br />

th<strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Burgundy</strong>. Average precipitation April<br />

through September <strong>in</strong> central Missouri is greater th<strong>an</strong><br />

averages reported for <strong>Burgundy</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Gotl<strong>an</strong>d.<br />

The relationship between monthly air temperature<br />

<strong>an</strong>d truffle harvest is not yet clear. Slightly lower<br />

average monthly temperatures on Gotl<strong>an</strong>d (Wedén<br />

et al. 2004b) result <strong>in</strong> earlier onset <strong>an</strong>d conclusion<br />

of <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fruit<strong>in</strong>g there th<strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>ce. In<br />

Missouri, April-October temperatures are warmer<br />

th<strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong> Europe, but the cool<strong>in</strong>g effect of greater<br />

precipitation may mitigate the effect of higher air<br />

temperature. We c<strong>an</strong> only speculate.<br />

M<strong>an</strong>ipulation of tree spac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d density permits the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle to be cultivated on modest slopes of<br />

almost <strong>an</strong>y aspect (for example, Chevalier et al. 2001).<br />

For example, on gentle south-fac<strong>in</strong>g slopes, the shade<br />

provided by a greater tree density <strong>an</strong>d/or closer<br />

spac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> east-west rows c<strong>an</strong> mitigate the dry<strong>in</strong>g<br />

effects of warmer temperature <strong>an</strong>d greater exposure<br />

to the sun.<br />

The <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus does not tolerate poorly<br />

dra<strong>in</strong>ed soils (“wet feet”), so flood pla<strong>in</strong>s are very<br />

<strong>in</strong>appropriate sites for trufficulture.<br />

Slope positions below wooded areas may conta<strong>in</strong><br />

especially high <strong>in</strong>oculum levels (“spore b<strong>an</strong>ks”)<br />

of competitor ectomycorrhizal fungi, s<strong>in</strong>ce both<br />

overl<strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>d groundwater dra<strong>in</strong>age of uphill<br />

wooded areas would certa<strong>in</strong>ly carry spores <strong>in</strong>to<br />

the l<strong>an</strong>dscape below. The two other ma<strong>in</strong> factors<br />

contribut<strong>in</strong>g to spore b<strong>an</strong>ks of ectomycorrhizal<br />

fungi on potential truffle pl<strong>an</strong>tation sites are: 1) the<br />

extension of ectomycorrhizal tree roots for 50-meters<br />

or more <strong>in</strong>to adjacent open areas; <strong>an</strong>d 2) the fecal<br />

deposits of <strong>an</strong>imals (for example, deer <strong>an</strong>d burrow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

rodents) that feed on various ectomycorrhizal<br />

mushrooms (for example, Ashk<strong>an</strong>nejhad <strong>an</strong>d Horton<br />

2006).<br />

L<strong>an</strong>d-use History<br />

It has been strongly <strong>an</strong>d justifiably recommended<br />

that truffle orchards be established on l<strong>an</strong>d that has<br />

not been occupied by ectomycorrhizal tree species<br />

for m<strong>an</strong>y years. Soils associated with previous<br />

ectomycorrhizal forest vegetation are pre-<strong>in</strong>fested<br />

with native ectomycorrhizal fungi well adapted to<br />

the site <strong>an</strong>d likely to compete effectively with the<br />

truffle fungus. Because the roots of trees extend <strong>in</strong>to<br />

open areas well beyond the extent of their c<strong>an</strong>opies,<br />

it has also been recommended that truffle orchards<br />

be surrounded by a 50-meter buffer of previously<br />

unforested l<strong>an</strong>d.<br />

Throughout the south-central U.S., a great deal of<br />

forested l<strong>an</strong>d was cleared dur<strong>in</strong>g the early 20th<br />

century <strong>an</strong>d converted at least temporarily to<br />

agriculture. Soil quality <strong>an</strong>d site productivity varied<br />

dramatically. Poorer sites were either ab<strong>an</strong>doned<br />

or grazed, <strong>an</strong>d better sites were often fertilized <strong>an</strong>d<br />

cropped. In contrast to conventional agriculture,<br />

truffle cultivation is most often successful on poor<br />

quality soils that have not been rout<strong>in</strong>ely fertilized.<br />

The <strong>in</strong>tensity of root colonization by truffle fungi is<br />

<strong>in</strong>versely related to soil fertility; seedl<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> fertile<br />

soils are capable of resist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>fection by mycorrhizal<br />

fungi.<br />

The presence of legumes may be a source of nitrogenfix<strong>in</strong>g<br />

bacteria for truffle development, but it rema<strong>in</strong>s<br />

to be determ<strong>in</strong>ed whether the same stra<strong>in</strong>s of bacteria<br />

that fix atmospheric nitrogen efficiently <strong>in</strong> legume<br />

nodules are also effective <strong>in</strong> association with the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus. The specificity of bacterial<br />

stra<strong>in</strong>s with different legumes is well known (Thrall<br />

et al. 2005), so truffle fungi also may perform best<br />

with their own uniquely adapted bacterial stra<strong>in</strong>s.<br />

Greenhouse trials with bacterial stra<strong>in</strong>s isolated from<br />

the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus need to be conducted.<br />

Soil Properties<br />

Much of what we know about appropriate soils<br />

for effective <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle cultivation is based<br />

on studies conducted with<strong>in</strong> the native (Europe<strong>an</strong>)<br />

r<strong>an</strong>ges of this truffle species. Yet we also know that<br />

some truffle species have been very successfully<br />

cultivated on rather different soils outside of Europe.<br />

Experience <strong>in</strong> New Zeal<strong>an</strong>d has demonstrated that<br />

7<br />

www.centerforagroforestry.org

Table 4. R<strong>an</strong>ges of soil characteristics for productive <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle sites <strong>in</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>ce (Chevalier <strong>an</strong>d Frochot, 1997), <strong>an</strong>d on the Swedish<br />

isl<strong>an</strong>d of Gotl<strong>an</strong>d (Wedén et al., 2004b). Data for Missouri represent <strong>an</strong> orchard pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g with established <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle mycorrhizae.<br />

Sweden<br />

Fr<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

Missouri<br />

Measured parameter Me<strong>an</strong> R<strong>an</strong>ge Me<strong>an</strong> R<strong>an</strong>ge R<strong>an</strong>ge<br />

Clay

formation (<strong>an</strong>d thus truffle production). This is why<br />

well-fertilized agricultural soils are not recommended<br />

as truffle pl<strong>an</strong>tation sites. Still, the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

fungus is deemed more toler<strong>an</strong>t th<strong>an</strong> the Périgord<br />

black truffle of relatively high phosphorus <strong>an</strong>d/or<br />

potassium levels (Chevalier et al. 2001).<br />

In addition to the clear requirement for high pH<br />

associated with high soil levels of Ca <strong>an</strong>d Mg, the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle thrives <strong>in</strong> soils with 9-12% org<strong>an</strong>ic<br />

matter, even as high as 20% (Chevalier et al. 2001,<br />

Wedén et al. 2004b). Fortunately, soil pH <strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>ic<br />

matter level c<strong>an</strong> be m<strong>an</strong>ipulated relatively easily <strong>an</strong>d<br />

<strong>in</strong>expensively with amendments of crushed limestone<br />

<strong>an</strong>d various forms of org<strong>an</strong>ic matter. Appropriate<br />

ratios of Ca:Mg <strong>an</strong>d K:Mg c<strong>an</strong> be approximately<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed by judicious selection of agricultural<br />

crushed dolomitic lime sources from with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

region.<br />

Technically, a soil’s pH value is its relative acidity,<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ed as the negative logarithm of the hydrogen ion<br />

concentration. A pH value of 7.0 is neutral (neither<br />

acidic nor alkal<strong>in</strong>e). Soils with pH values below<br />

7.0 are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly acidic (higher concentrations<br />

of hydrogen ions), whereas pH values greater th<strong>an</strong><br />

7.0 <strong>in</strong>dicate <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g alkal<strong>in</strong>ity (lower hydrogen<br />

ion concentrations as a result of higher calcium,<br />

magnesium <strong>an</strong>d potassium ion concentrations).<br />

Unlike most agronomic crops, the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

fungus clearly requires a soil pH above 7.0 for<br />

fruit<strong>in</strong>g (Riousset et al. 2001).<br />

Nutrient-hold<strong>in</strong>g capacity is directly related to a<br />

soil’s clay <strong>an</strong>d org<strong>an</strong>ic matter content. The <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle thrives with moderate levels of clay <strong>an</strong>d<br />

org<strong>an</strong>ic matter (Chevalier et al. 2001, Wedén et al.<br />

2004b), as long as the soil is well-aerated <strong>an</strong>d freely<br />

dra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (Riousset et al. 2001). Soil dra<strong>in</strong>age c<strong>an</strong><br />

become restricted at high levels of clay content, but<br />

clay particles tend to aggregate at the high pH levels<br />

favored by the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle, improv<strong>in</strong>g soil<br />

aeration <strong>an</strong>d dra<strong>in</strong>age.<br />

Figure 1 highlights the r<strong>an</strong>ge of soil textures<br />

associated with productive truffle pl<strong>an</strong>tations known<br />

from Fr<strong>an</strong>ce, Italy <strong>an</strong>d Gotl<strong>an</strong>d (Chevalier et al. 2001).<br />

Despite signific<strong>an</strong>t overlaps the r<strong>an</strong>ges of soil texture<br />

associated with <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle habitat differ<br />

subst<strong>an</strong>tially among these three regions. Will data<br />

from new regions extend the r<strong>an</strong>ge of soil textures<br />

known to support <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle production? The<br />

red l<strong>in</strong>es demonstrate how to p<strong>in</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t the soil texture<br />

of a typical Missouri silt loam soil.<br />

Access to Water – Irrigation<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, pl<strong>an</strong>tation sites with access to water for<br />

seasonal irrigation have a dist<strong>in</strong>ct adv<strong>an</strong>tage over<br />

sites where irrigation is not feasible. We have already<br />

mentioned the relationship between grow<strong>in</strong>g season<br />

precipitation <strong>an</strong>d truffle harvest (see “Climate <strong>an</strong>d<br />

L<strong>an</strong>dscape Position,” above), <strong>an</strong>d the south-central<br />

U.S. often experiences a dry mid-summer period. It<br />

is widely believed that the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus<br />

forms truffle mushroom primordia dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

spr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d summer. Unlike most other mushrooms,<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffles apparently develop slowly over a<br />

period of months before matur<strong>in</strong>g to their full size<br />

<strong>an</strong>d fragr<strong>an</strong>ce. Thus, for maximum productivity,<br />

growers should be prepared to supplement natural<br />

precipitation with overhead irrigation every two<br />

weeks from late spr<strong>in</strong>g through early autumn to<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> optimum levels of precipitation. (See<br />

“Irrigation,” under “Orchard Site Preparation,”<br />

below.)<br />

Top: Spr<strong>in</strong>g-form rakes are widely used<br />

for <strong>in</strong>corporation of lime <strong>an</strong>d other<br />

amendments <strong>in</strong> truffle site preparation<br />

<strong>an</strong>d ma<strong>in</strong>ten<strong>an</strong>ce. The disadv<strong>an</strong>tage<br />

to this tool is that it drags roots through<br />

the soil, which c<strong>an</strong> spread unw<strong>an</strong>ted<br />

compet<strong>in</strong>g mycorrhizal fungi around<br />

the pl<strong>an</strong>tation. Middle <strong>an</strong>d bottom: Two<br />

implements useful <strong>in</strong> establish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle pl<strong>an</strong>tations<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Lorra<strong>in</strong>e, Fr<strong>an</strong>ce. Middle:<br />

The comb at the top of the blade is<br />

used to clear heavy grass or brush,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d the blade is used to aerate the soil<br />

to 2-ft. depth <strong>in</strong> prepar<strong>in</strong>g the pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g<br />

bed. A key feature of the tool is the two<br />

side w<strong>in</strong>gs that loosen the soil laterally<br />

<strong>in</strong> addition to the vertical slic<strong>in</strong>g<br />

accomplished by the blade. One result<br />

is that no air pockets are left <strong>in</strong> the soil.<br />

Bottom: This device is used <strong>in</strong> the very<br />

early spr<strong>in</strong>g to regenerate f<strong>in</strong>e roots <strong>in</strong><br />

the pl<strong>an</strong>tation. The 8-<strong>in</strong>. teeth accomplish<br />

both aeration <strong>an</strong>d disturb<strong>an</strong>ce of<br />

lateral roots. New f<strong>in</strong>e roots grow <strong>in</strong>to<br />

the disturbed upper soil as quickly as<br />

two months after treatment. In contrast<br />

to the spr<strong>in</strong>g-form rake, this tool is not<br />

dragged across the pl<strong>an</strong>tation; <strong>in</strong>stead<br />

it is repeatedly moved <strong>an</strong>d rocked to<br />

accomplish slic<strong>in</strong>g without dragg<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

9<br />

www.centerforagroforestry.org

Pl<strong>an</strong>tation Site Preparation<br />

Once <strong>an</strong> appropriate orchard site has been selected,<br />

the first steps <strong>in</strong> truffle cultivation are to make <strong>an</strong>y<br />

desirable soil modifications <strong>an</strong>d to <strong>in</strong>stall other useful<br />

<strong>in</strong>frastructure.<br />

Soil Amendment<br />

The most critical soil modification is the adjustment<br />

of soil pH by the addition of lime to the upper 30 cm<br />

(12 <strong>in</strong>) of soil. Rais<strong>in</strong>g the pH <strong>in</strong>to the appropriate<br />

r<strong>an</strong>ge may however affect the availability of other<br />

import<strong>an</strong>t pl<strong>an</strong>t nutrients (for example, iron,<br />

magnesium, phosphorus <strong>an</strong>d trace elements). For<br />

this reason, there are nutritional adv<strong>an</strong>tages to us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

crushed dolomitic limestone, especially “reddish”<br />

forms that conta<strong>in</strong> subst<strong>an</strong>tial qu<strong>an</strong>tities of iron as<br />

well as magnesium. Generally, amendment of levels<br />

of iron, phosphorus <strong>an</strong>d trace nutrients (if necessary)<br />

may be best made after pl<strong>an</strong>tation establishment,<br />

based on <strong>an</strong>alysis of foliar nutrient content, if nutrient<br />

deficiency is evident (Hall et al. 2007).<br />

A rule of thumb suggests that approximately 1-1.5<br />

tons per hectare of f<strong>in</strong>ely crushed limestone are<br />

required to raise the pH of a soil by 0.1 pH unit for<br />

each 10 cm of soil depth be<strong>in</strong>g treated (Hall et al.,<br />

2007). Additional chip-sized limestone (0.5-1 ton per<br />

hectare) c<strong>an</strong> be added to provide buffer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

future. Because it may take up to a year for soil pH to<br />

equilibrate after lim<strong>in</strong>g, it may be necessary to apply<br />

lime more th<strong>an</strong> once <strong>in</strong> prepar<strong>in</strong>g the pl<strong>an</strong>tation site,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d because the lime needs to be thoroughly mixed<br />

<strong>in</strong>to the soil, trees should not be pl<strong>an</strong>ted until <strong>an</strong><br />

acceptable pH level (at least 7.5) has been achieved.<br />

The most appropriate form of lime is generally a<br />

crushed dolomitic limestone, conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g subst<strong>an</strong>tial<br />

levels of magnesium (<strong>an</strong>d ideally iron) as well as<br />

calcium, because the calcium/magnesium bal<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

is import<strong>an</strong>t to pl<strong>an</strong>t nutrition, <strong>an</strong>d because iron<br />

becomes less available to pl<strong>an</strong>ts as the pH <strong>in</strong>creases.<br />

If sufficient iron is not naturally available (based on<br />

appear<strong>an</strong>ce of characteristic symptoms of stunted<br />

growth <strong>an</strong>d yellow<strong>in</strong>g foliage), it c<strong>an</strong> be applied as a<br />

supplemental foliar spray.<br />

Lim<strong>in</strong>g materials are available <strong>in</strong> several forms,<br />

which vary <strong>in</strong> their nutritional content <strong>an</strong>d rate of<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>in</strong>to the soil. Agricultural or pelletized<br />

lime (pel lime) <strong>in</strong>corporates <strong>in</strong>to the soil more<br />

rapidly th<strong>an</strong> dolomitic lime but does not contribute<br />

signific<strong>an</strong>tly to levels of iron, magnesium or other<br />

m<strong>in</strong>erals. Depend<strong>in</strong>g on various factors, it may take<br />

a year for soil pH to equilibrate after <strong>in</strong>corporation<br />

of a dolomitic lime treatment <strong>in</strong>to the upper 1-ft<br />

(30-cm) of soil. Because currently available models<br />

of pH response to lime treatments are unreliable at<br />

pH values above 7.0, it’s best to modify orchard site<br />

soil pH <strong>in</strong> stages so as not to raise soil pH above 8.0.<br />

Thus, one should pl<strong>an</strong> for orchard soil preparation<br />

to take at least two years. There are m<strong>an</strong>y different<br />

k<strong>in</strong>ds of implements that c<strong>an</strong> be used to <strong>in</strong>corporate<br />

soil amendments. The objective is to <strong>in</strong>corporate<br />

amendments as uniformly as possible without<br />

destroy<strong>in</strong>g soil structure. Too m<strong>an</strong>y passes over a site<br />

c<strong>an</strong> “polish” the <strong>in</strong>terface between the amended soil<br />

<strong>an</strong>d the subsoil, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> poor dra<strong>in</strong>age. Because<br />

each lime application needs to be <strong>in</strong>corporated fairly<br />

uniformly <strong>in</strong>to the soil, amendment needs to be<br />

completed before <strong>in</strong>fected trees are pl<strong>an</strong>ted on the<br />

site to avoid damag<strong>in</strong>g develop<strong>in</strong>g root systems. The<br />

spr<strong>in</strong>g-form rake depicted <strong>in</strong> Figure X is commonly<br />

used to <strong>in</strong>corporate supplemental lime <strong>in</strong>to pl<strong>an</strong>tation<br />

soil.<br />

Weed M<strong>an</strong>agement<br />

Exist<strong>in</strong>g vegetation on orchard sites competes with<br />

truffle seedl<strong>in</strong>g root systems for space, water <strong>an</strong>d<br />

nutrients. On the other h<strong>an</strong>d, short-lived pl<strong>an</strong>t<br />

roots contribute org<strong>an</strong>ic matter while loosen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

soil structure, <strong>an</strong>d legumes contribute valuable<br />

nitrogen to the soil. Other pl<strong>an</strong>ts may contribute to<br />

development of a <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle ecosystem <strong>in</strong><br />

ways still unknown.<br />

Nevertheless, too much weedy vegetation c<strong>an</strong><br />

acidify the soil as org<strong>an</strong>ic matter decomposes<br />

to produce weak acids. Thus it is common<br />

practice to reduce compet<strong>in</strong>g vegetation prior to<br />

pl<strong>an</strong>tation establishment. Vegetation control c<strong>an</strong> be<br />

accomplished us<strong>in</strong>g mulch<strong>in</strong>g materials, herbicides,<br />

graz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>imals or by very close mow<strong>in</strong>g. The<br />

herbicides Roundup® (glyphosate) <strong>an</strong>d Buster®<br />

(glufos<strong>in</strong>ate-ammonium) seem to be well tolerated<br />

by the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fungus (Chevalier et al. 2001)<br />

though care must be taken not to let these herbicides<br />

drift onto tree foliage! The effects of m<strong>an</strong>y different<br />

mulch<strong>in</strong>g materials <strong>an</strong>d fabrics are yet unclear but it<br />

has been demonstrated that the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle c<strong>an</strong><br />

benefit from vegetation control us<strong>in</strong>g black, waterpermeable<br />

mulch<strong>in</strong>g fabric (Zambonelli et al. 2005).<br />

Mow<strong>in</strong>g has the tw<strong>in</strong> disadv<strong>an</strong>tages of be<strong>in</strong>g time<br />

consum<strong>in</strong>g while also contribut<strong>in</strong>g to soil compaction<br />

over time.<br />

The Center for <strong>Agroforestry</strong> at the University of Missouri<br />

10

Weedy tree species on <strong>an</strong> orchard site need to be<br />

treated accord<strong>in</strong>g to their mycorrhizal character (EM<br />

or AM). Because the tree species most commonly<br />

associated with the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle (hazels <strong>an</strong>d<br />

oaks) are EM, the presence of AM trees does not<br />

pose a threat of mycorrhizal fungus competition to<br />

the truffle fungus, <strong>an</strong>d the AM trees may contribute<br />

useful shade. If direct competition between AM <strong>an</strong>d<br />

truffle trees is considered problematic, the AM trees<br />

c<strong>an</strong> simply be removed from the site. On the other<br />

h<strong>an</strong>d, EM trees <strong>in</strong> the vic<strong>in</strong>ity of <strong>an</strong> orchard should<br />

be treated differently. When possible, orchards<br />

should be located at some dist<strong>an</strong>ce from natural EM<br />

woodl<strong>an</strong>ds to reduce competition between native<br />

EM fungi <strong>an</strong>d the cultivated truffle fungus. If native<br />

EM trees occur on <strong>an</strong> orchard site, it’s preferable to<br />

cut them off <strong>an</strong>d poison the stump rather th<strong>an</strong> try<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to remove the stump <strong>an</strong>d root system from the soil.<br />

Invariably, efforts to remove root systems leave<br />

mycorrhizal f<strong>in</strong>e roots <strong>in</strong> the soil <strong>an</strong>d have the effect<br />

of spread<strong>in</strong>g EM fungi with<strong>in</strong> the orchard site. Table<br />

4 presents a list of tree genera commonly associated<br />

with AM or EM fungi.<br />

Irrigation<br />

<strong>Truffle</strong> orchard development <strong>an</strong>d fruit<strong>in</strong>g both<br />

benefit from adequate soil moisture year-round.<br />

While truffle fungi do not like “wet feet,” develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

truffles are damaged dur<strong>in</strong>g prolonged dry periods.<br />

The mid-summer period is particularly critical <strong>in</strong><br />

the truffle life cycle because young truffles become<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent of their orig<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g root system <strong>an</strong>d are<br />

especially vulnerable to desiccation.<br />

Overhead irrigation is much superior to drip<br />

irrigation because:<br />

1) It provides moisture to truffles wherever they may<br />

be develop<strong>in</strong>g;<br />

2) It favors the development of a wider-spread<strong>in</strong>g<br />

root system.<br />

Fenc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Perhaps the f<strong>in</strong>al element of orchard site preparation<br />

is the fenc<strong>in</strong>g of the area for exclusion of unw<strong>an</strong>ted<br />

<strong>an</strong>imals (both two- <strong>an</strong>d four-legged species). Fences<br />

are generally warr<strong>an</strong>ted where trespass by deer,<br />

livestock, feral hogs or people are a concern. Fences<br />

for exclusion of deer are commonly 10 ft. tall,<br />

constructed of heavy wire with a closer mesh at the<br />

bottom for exclusion of smaller <strong>an</strong>imals (goats, sheep,<br />

rabbits). Feral hogs c<strong>an</strong> be discouraged from digg<strong>in</strong>g<br />

under the fence by extend<strong>in</strong>g it approximately 2 ft.<br />

below ground, curv<strong>in</strong>g outward from the orchard<br />

up to 3 ft. There may be some added adv<strong>an</strong>tage to<br />

<strong>in</strong>stall<strong>in</strong>g str<strong>an</strong>ds of solar-powered electrified wire<br />

1-3 ft. above ground, 1 ft. outside the fence. The<br />

illustration below presents a fence of this type.<br />

Deer- <strong>an</strong>d<br />

hog-proof<br />

fence surround<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle truffière<br />

site at the Maison de la Truffe museum <strong>in</strong> Boncourt-sur-Meuse,<br />

the Lorra<strong>in</strong>e, Fr<strong>an</strong>ce. A unique<br />

feature is that the fence extends 0.5 meters below<br />

the soil surface, curv<strong>in</strong>g outward away from<br />

the truffière for about 1 meter. The below-ground<br />

extension of the fence prevents all but the most<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>an</strong>imals (badgers, for example, see<br />

<strong>in</strong>set photo) from burrow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to the truffière.<br />

Missouri climates commonly feature a dry summer<br />

period. It is advisable to provide the equivalent of a<br />

summer shower to prevent dry periods of more th<strong>an</strong><br />

two weeks’ duration. (See ”Climate <strong>an</strong>d L<strong>an</strong>dscape<br />

Position” under “Characteristics of a Good <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

<strong>Truffle</strong> Pl<strong>an</strong>tation Site,” above.) Both precipitation<br />

<strong>an</strong>d irrigation have the additional benefit of<br />

moderat<strong>in</strong>g high summer soil temperatures.<br />

Pl<strong>an</strong>tation Establishment<br />

One major difference between the preferred habitats<br />

of the <strong>Burgundy</strong> vs. Périgord truffles <strong>in</strong>volves<br />

openness of the orchard floor. Périgord truffle<br />

development is favored by full access of sunlight<br />

to the orchard floor, whereas fruit<strong>in</strong>g by the<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle is favored by subst<strong>an</strong>tial shade<br />

<strong>an</strong>d development of a litter layer. In fact, it is widely<br />

11<br />

www.centerforagroforestry.org

elieved that the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fruits poorly<br />

if at all until c<strong>an</strong>opy closure occurs. As a result,<br />

there is a longer <strong>in</strong>terval between pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>an</strong>d<br />

harvest of <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffles th<strong>an</strong> is the case with<br />

Périgord truffles (approximately eight vs. five years,<br />

respectively).<br />

Pl<strong>an</strong>t Density<br />

The pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g design <strong>an</strong>d tree density <strong>in</strong> a truffle<br />

pl<strong>an</strong>tation needs to take <strong>in</strong>to consideration the<br />

species of truffle be<strong>in</strong>g cultivated, the tree species<br />

selected, <strong>an</strong>d site characteristics. Further, pl<strong>an</strong>tation<br />

tree density <strong>an</strong>d tree species composition may need<br />

to be adjusted as the pl<strong>an</strong>tation matures.<br />

Because the <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle benefits from shade<br />

<strong>an</strong>d a litter layer, tree densities will generally<br />

be much higher <strong>in</strong> <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle pl<strong>an</strong>tations<br />

(perhaps 400-1200 trees/ha) th<strong>an</strong> <strong>in</strong> pl<strong>an</strong>tations of<br />

the Périgord truffle which thrives with full access of<br />

sun to the soil (400 trees/ha or fewer) (Chevalier et<br />

al. 2001). Tree density c<strong>an</strong> be reduced as trees grow<br />

<strong>an</strong>d beg<strong>in</strong> to cast shade. Perhaps the most obvious<br />

approach would be to pl<strong>an</strong>t <strong>in</strong>fected seedl<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

more densely, but <strong>in</strong>fected seedl<strong>in</strong>gs are quite<br />

expensive <strong>an</strong>d would eventually need to be th<strong>in</strong>ned.<br />

An alternative approach would be to <strong>in</strong>terpl<strong>an</strong>t<br />

truffle <strong>in</strong>oculated trees among previously-pl<strong>an</strong>ted<br />

arbuscular mycorrhizal “shelter trees” (see Table<br />

1), whose sole purpose is to provide early shade to<br />

hasten the onset of fruit<strong>in</strong>g (Wehrlen et al. 2009).<br />

A very productive,<br />

centuriesold<br />

hazel grove<br />

on Gotl<strong>an</strong>d. Note<br />

the closed c<strong>an</strong>opy<br />

that seems to<br />

be a requirement<br />

for abund<strong>an</strong>t<br />

<strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle<br />

fruit<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

A typical <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle pl<strong>an</strong>tation<br />

(mostly Europe<strong>an</strong> hazel,<br />

<strong>in</strong>set), located <strong>in</strong> Boncourt-sur-<br />

Meuse (the Lorra<strong>in</strong>e, Fr<strong>an</strong>ce).<br />

Because hazels are generally smaller <strong>an</strong>d shorterlived<br />

th<strong>an</strong> oaks, yet beg<strong>in</strong> to produce truffles at <strong>an</strong><br />

earlier age th<strong>an</strong> oaks, it is possible to alternate oaks<br />

<strong>an</strong>d hazels with<strong>in</strong> pl<strong>an</strong>tation rows with the <strong>in</strong>tention<br />

of gradually remov<strong>in</strong>g hazels as the pl<strong>an</strong>tation<br />

matures (Hall et al. 2007).<br />

Tree densities <strong>in</strong> <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle pl<strong>an</strong>tations should<br />

be lower under conditions favor<strong>in</strong>g rapid tree growth<br />

<strong>an</strong>d/or larger tree stature (Chevalier et al. 2001), such<br />

as fertile <strong>an</strong>d/or deep soils, access to irrigation, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

<strong>in</strong> pl<strong>an</strong>tations of tree species which atta<strong>in</strong> greater<br />

stature at maturity (oaks compared to hazels, for<br />

example). Pl<strong>an</strong>tation density c<strong>an</strong> also be lower on<br />

north-fac<strong>in</strong>g slopes th<strong>an</strong> on other aspects (due to<br />

greater natural shade).<br />

Comp<strong>an</strong>ion Pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

Weeds have been loosely def<strong>in</strong>ed as pl<strong>an</strong>ts that are<br />

grow<strong>in</strong>g where you don’t w<strong>an</strong>t them. However,<br />

a number of woody <strong>an</strong>d herbaceous pl<strong>an</strong>t species<br />

are suspected of contribut<strong>in</strong>g to truffle habitat <strong>an</strong>d<br />

nutrition.<br />

It has recently been shown that a variety of bacteria<br />

related to those that fix nitrogen <strong>in</strong> legume nodules<br />

occur <strong>in</strong> large numbers with<strong>in</strong> truffle fruit bodies.<br />

In our ongo<strong>in</strong>g studies of bacterial communities<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>Burgundy</strong> truffle fruit bodies, we have<br />

recently isolated <strong>in</strong>to pure culture nitrogen-fix<strong>in</strong>g<br />

bacteria closely related to stra<strong>in</strong>s of Bradyrhizobium<br />

<strong>an</strong>d S<strong>in</strong>orhizobium melilloti commonly used<br />

<strong>in</strong> agriculture. Itali<strong>an</strong> colleagues have now<br />

demonstrated nitrogen fixation with<strong>in</strong> fruit bodies<br />

of T. borchii Vitt. (<strong>an</strong>other truffle species) by the<br />

acetylene reduction technique (Barbieri et al. 2010).<br />

This raises the question of whether or not the nitrogen<br />

produced by these bacteria is essential to mycorrhizae<br />

formation <strong>an</strong>d/or fruit<strong>in</strong>g of truffle fungi. If the<br />

The Center for <strong>Agroforestry</strong> at the University of Missouri<br />

12

<strong>an</strong>swer is “yes,” then modest populations of nitrogenfix<strong>in</strong>g<br />

hosts might ensure the well-distributed<br />

presence of these bacteria across a truffle orchard site.<br />

It may also prove adv<strong>an</strong>tageous to simult<strong>an</strong>eously<br />

<strong>in</strong>oculate seedl<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> the greenhouse with selected<br />

bacterial stra<strong>in</strong>s as well as the desired truffle fungus.<br />

Pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g<br />

There are m<strong>an</strong>y ways to “put a tree <strong>in</strong> the ground”!<br />

But <strong>in</strong> establish<strong>in</strong>g a truffle pl<strong>an</strong>tation, we are<br />

pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g precious tree seedl<strong>in</strong>gs pa<strong>in</strong>stak<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

produced to be well-colonized by the <strong>Burgundy</strong><br />

truffle fungus <strong>in</strong>to ground that has been carefully<br />

prepared to support truffle development. Wouldn’t<br />

it be a shame to pl<strong>an</strong>t these expensive trees <strong>in</strong> <strong>an</strong>y<br />

sub-optimum m<strong>an</strong>ner? So what do we know about<br />

properly pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g truffle seedl<strong>in</strong>gs?<br />

We c<strong>an</strong> learn from a technique that is currently<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g favor <strong>in</strong> Fr<strong>an</strong>ce. In this technique, developed<br />

jo<strong>in</strong>tly by the French INRA <strong>an</strong>d equipment<br />

m<strong>an</strong>ufacturer Claude Becker (Toul, Fr<strong>an</strong>ce), pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g<br />

beds 1 meter wide are prepared along the slope<br />

contour us<strong>in</strong>g Becker’s “culti-sous-soleur” tool (see<br />

center image, pg. 9). The comb above the blade is<br />

first used to rake away larger herbaceous vegetation<br />

<strong>an</strong>d brush. The w<strong>in</strong>ged blade is then used to loosen<br />

the soil to a depth of 0.6 meter without overturn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the soil horizons. Three strokes are made with the<br />

blade; the first stroke def<strong>in</strong>es the center of the row.<br />

The second <strong>an</strong>d third strokes are made parallel to the<br />

first, 0.5 meters to each side with the blade <strong>an</strong>gled to<br />

br<strong>in</strong>g soil toward the center, form<strong>in</strong>g a raised bed 0.2-<br />

0.4 meters high. An import<strong>an</strong>t feature of this method<br />

is that strokes are discont<strong>in</strong>uous along the pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g<br />

bed, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imal dragg<strong>in</strong>g of debris (roots,<br />

etc.) across the site. A skilled operator c<strong>an</strong> produce<br />

100 meters of pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g bed, 1 meter wide, per hour.<br />

While this tool will not be available everywhere, <strong>an</strong>y<br />

pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g bed preparation technique that emulates this<br />

effect would be helpful.<br />

Once the raised pl<strong>an</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g bed has been formed, it is<br />

import<strong>an</strong>t to pl<strong>an</strong>t seedl<strong>in</strong>gs at the appropriate depth.<br />

Oaks <strong>an</strong>d hazels should be pl<strong>an</strong>ted with the soil level<br />

approximately at the po<strong>in</strong>t of attachment of the acorn<br />

or nut.<br />

Rabbits <strong>an</strong>d mice c<strong>an</strong> cause serious damage to young<br />

seedl<strong>in</strong>gs by eat<strong>in</strong>g twigs <strong>an</strong>d/or girdl<strong>in</strong>g seedl<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

(eat<strong>in</strong>g the tender bark). In areas where rodents<br />

abound, seedl<strong>in</strong>gs need to be protected by mesh or<br />

solid tubes (for example, Wedén et al. 2009).<br />

Pl<strong>an</strong>tation Ma<strong>in</strong>ten<strong>an</strong>ce<br />