- Page 1 and 2:

This content is copyright Flat Worl

- Page 3 and 4:

The Economics of Poverty The Econom

- Page 5 and 6:

Carlos Aguilar El Paso Community Co

- Page 7 and 8:

the opportunity to be active learne

- Page 9 and 10:

One person’s use of gravity is no

- Page 11 and 12:

Case in Point: The Rising Cost of E

- Page 13 and 14:

Opportunity Costs Are Important If

- Page 15 and 16:

as well as the ranking for each of

- Page 17 and 18:

TRY IT! The Department of Agricultu

- Page 19 and 20:

assumed conditions that are simpler

- Page 21 and 22:

Case in Point: Does Baldness Cause

- Page 23 and 24:

PROBLEMS 1. Why does the fact that

- Page 25 and 26:

for the production of goods and ser

- Page 27 and 28:

TRY IT! Explain whether each of the

- Page 29 and 30:

USA Today, August 30, 2001, p. 1B;

- Page 31 and 32:

Figure 2.3 The Slope of a Productio

- Page 33 and 34:

the firm were to produce 100 snowbo

- Page 35 and 36:

At point A, the economy was produci

- Page 37 and 38:

Points on the production possibilit

- Page 39 and 40:

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM The produ

- Page 41 and 42:

An increase in the physical quantit

- Page 43 and 44: Resources society could have used t

- Page 45 and 46: e that higher incomes lead nations

- Page 47 and 48: has increased the welfare of people

- Page 49 and 50: CONCEPT PROBLEMS 1. How does a coll

- Page 51 and 52: producing bowling balls? Bicycles?

- Page 53 and 54: and a lower price tends to increase

- Page 55 and 56: Just as demand can increase, it can

- Page 57 and 58: Heads Up! Figure 3.5 It is crucial

- Page 59 and 60: ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM Since goi

- Page 61 and 62: Figure 3.9 An Increase in Supply If

- Page 63 and 64: Heads Up! There are two special thi

- Page 65 and 66: “The chickens didn’t stop layin

- Page 67 and 68: Figure 3.15 A Surplus in the Market

- Page 69 and 70: An Increase in Demand An increase i

- Page 71 and 72: Figure 3.19 Simultaneous Decreases

- Page 73 and 74: Figure 3.21 The Circular Flow of Ec

- Page 75 and 76: Case in Point: Demand, Supply, and

- Page 77 and 78: CONCEPT PROBLEMS 1. What do you thi

- Page 79 and 80: NUMERICAL PROBLEMS Problems 1-5 are

- Page 81 and 82: In the third section of the chapter

- Page 83 and 84: Figure 4.2 The Increasing Demand fo

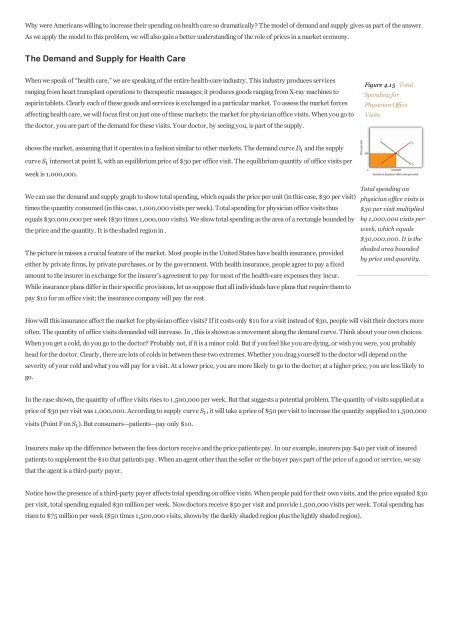

- Page 85 and 86: The intersection of the demand and

- Page 87 and 88: Case in Point: 9/11 and the Stock M

- Page 89 and 90: The Great Depression of the 1930s l

- Page 91 and 92: 120. These distortions have grown o

- Page 93: ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM A minimum

- Page 97 and 98: were explicitly stated, political p

- Page 99 and 100: CONCEPT PROBLEMS 1. Like personal c

- Page 101 and 102: A good deal of the economy’s mome

- Page 103 and 104: At time t 1 in , an expansion ends

- Page 105 and 106: Case in Point: The Art of Predictin

- Page 107 and 108: Concern about changes in the price

- Page 109 and 110: epay their loans. Deflation was com

- Page 111 and 112: of each component of consumption sp

- Page 113 and 114: Sources of Bias 1997 Estimate 2006

- Page 115 and 116: ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM Rearrangi

- Page 117 and 118: employment. It is sometimes referre

- Page 119 and 120: KEY TAKEAWAYS People who are not wo

- Page 121 and 122: ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM In Year 1

- Page 123 and 124: NUMERICAL PROBLEMS 1. Plot the quar

- Page 125 and 126: The primary measure of the ups and

- Page 127 and 128: By recording additions to inventori

- Page 129 and 130: Figure 6.5 Spending in the Circular

- Page 131 and 132: TRY IT! Here is a two-part exercise

- Page 133 and 134: ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM 1. GDP eq

- Page 135 and 136: generated in the production of thos

- Page 137 and 138: Case in Point: The GDP-GDI Gap Figu

- Page 139 and 140: that productivity has increased gre

- Page 141 and 142: Figure 6.9 Comparing Per Capita Rea

- Page 143 and 144: ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM 1. Real G

- Page 145 and 146:

NUMERICAL PROBLEMS 1. Given the fol

- Page 147 and 148:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Define poten

- Page 149 and 150:

Figure 7.2 Changes in Aggregate Dem

- Page 151 and 152:

Equation 7.1 We use the capital Gre

- Page 153 and 154:

7.2 Aggregate Demand and Aggregate

- Page 155 and 156:

The Short Run Analysis of the macro

- Page 157 and 158:

Finally, minimum wage laws prevent

- Page 159 and 160:

Figure 7.10 An Increase in Governme

- Page 161 and 162:

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM All compo

- Page 163 and 164:

Now suppose aggregate demand increa

- Page 165 and 166:

price level of P 3 . For both kinds

- Page 167 and 168:

Case in Point: Survey of Economists

- Page 169 and 170:

CONCEPT PROBLEMS 1. Explain how the

- Page 171 and 172:

Aggregate Quantity of Goods and Ser

- Page 173 and 174:

2. We define growth in terms of the

- Page 175 and 176:

Figure 8.3 Differences in Growth Ra

- Page 177 and 178:

Case in Point: Presidents and Econo

- Page 179 and 180:

Figure 8.6 The Aggregate Production

- Page 181 and 182:

Figure 8.9 Increase in the Supply o

- Page 183 and 184:

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM The produ

- Page 185 and 186:

In general, countries with accelera

- Page 187 and 188:

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM Situation

- Page 189 and 190:

NUMERICAL PROBLEMS 1. The populatio

- Page 191 and 192:

not get eaten. Prisoners knew other

- Page 193 and 194:

circulation. Unless a means can be

- Page 195 and 196:

KEY TAKEAWAYS Money is anything tha

- Page 197 and 198:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Explain what

- Page 199 and 200:

Acme Bank Assets Liabilities Reserv

- Page 201 and 202:

Figure 9.7 Notice that Bellville is

- Page 203 and 204:

per insured bank, for each account

- Page 205 and 206:

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM 1. Acme B

- Page 207 and 208:

discount rate. Lowering the discoun

- Page 209 and 210:

Case in Point: Fed Supports the Fin

- Page 211 and 212:

CONCEPT PROBLEMS 1. Airlines have

- Page 213 and 214:

a. 10%. b. 15%. c. 20%. d. 25%. 10.

- Page 215 and 216:

price. Buyers of bonds will seek th

- Page 217 and 218:

trade-weighted exchange rate index

- Page 219 and 220:

Case in Point: Betting on a Plunge

- Page 221 and 222:

Of course, money is money. One cann

- Page 223 and 224:

The speculative demand for money is

- Page 225 and 226:

Equilibrium in the Market for Money

- Page 227 and 228:

The reduction in interest rates req

- Page 229 and 230:

Economic Perspectives 29 (First Qua

- Page 231 and 232:

NUMERICAL PROBLEMS 1. Compute the r

- Page 233 and 234:

ased on a section of the Federal Re

- Page 235 and 236:

an oil-price boost that came in the

- Page 237 and 238:

Figure 11.2 A Contractionary Moneta

- Page 239 and 240:

Case in Point: A Brief History of t

- Page 241 and 242:

Only after policy makers recognize

- Page 243 and 244:

The Degree of Impact on the Economy

- Page 245 and 246:

Regardless of where one stands on t

- Page 247 and 248:

11.3 Monetary Policy and the Equati

- Page 249 and 250:

velocity is constant when viewed ov

- Page 251 and 252:

First, we do not expect a given per

- Page 253 and 254:

Summary Part of the Fed’s power s

- Page 255 and 256:

chosen. 11. Since August 1997, the

- Page 257 and 258:

. 1% c. 2% 7. Suppose the velocity

- Page 259 and 260:

A number of changes have influenced

- Page 261 and 262:

The Government Budget Balance The g

- Page 263 and 264:

KEY TAKEAWAYS Over the last 50 year

- Page 265 and 266:

ANSWER TO TRY IT! PROBLEM A budget

- Page 267 and 268:

A reduction in government purchases

- Page 269 and 270:

Case in Point: Post-World War II Ex

- Page 271 and 272:

Our analysis of monetary policy sho

- Page 273 and 274:

Case in Point: Crowding Out in Cana

- Page 275 and 276:

NUMERICAL PROBLEMS 1. Look up the t

- Page 277 and 278:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Explain and

- Page 279 and 280:

Equation 13.3 The saving function r

- Page 281 and 282:

Other Determinants of Consumption T

- Page 283 and 284:

Case in Point: Consumption and the

- Page 285 and 286:

that firms did not intend to make.

- Page 287 and 288:

Equation 13.11 Equation 13.11 is th

- Page 289 and 290:

Figure 13.10 Adjusting to Equilibri

- Page 291 and 292:

inducing a further change in the le

- Page 293 and 294:

There are two major differences bet

- Page 295 and 296:

Case in Point: Fiscal Policy in the

- Page 297 and 298:

This is called the interest rate ef

- Page 299 and 300:

Case in Point: Predicting the Impac

- Page 301 and 302:

Summary This chapter presented the

- Page 303 and 304:

NUMERICAL PROBLEMS 1. Suppose the f

- Page 305 and 306:

only major part of investment left

- Page 307 and 308:

Figure 14.2 "Gross Private Domestic

- Page 309 and 310:

KEY TAKEAWAYS Investment adds to th

- Page 311 and 312:

We will see in this section that in

- Page 313 and 314:

Firms need capital to produce goods

- Page 315 and 316:

TRY IT! Show how the investment dem

- Page 317 and 318:

Figure 14.10 A Change in Investment

- Page 319 and 320:

Summary Investment is an addition t

- Page 321 and 322:

a. Draw the investment demand curve

- Page 323 and 324:

of the first meeting in Doha, Qatar

- Page 325 and 326:

Figure 15.2 U.S. Real GDP and Impor

- Page 327 and 328:

KEY TAKEAWAYS International trade a

- Page 329 and 330:

ANSWERS TO TRY IT! PROBLEMS 1. Mexi

- Page 331 and 332:

Equation 15.3 represents an extreme

- Page 333 and 334:

KEY TAKEAWAYS The balance of paymen

- Page 335 and 336:

ANSWERS TO TRY IT! PROBLEMS 1. All

- Page 337 and 338:

Countries that have a floating exch

- Page 339 and 340:

ecame fully adopted in 1999. Since

- Page 341 and 342:

Case in Point: The Euro Figure 15.1

- Page 343 and 344:

CONCEPT PROBLEMS 1. David Ricardo,

- Page 345 and 346:

a. If the exchange rate was free-fl

- Page 347 and 348:

The Phillips curve seemed to make g

- Page 349 and 350:

increases. The term, coined by Mass

- Page 351 and 352:

16.2 Explaining Inflation-Unemploym

- Page 353 and 354:

Figure 16.9 The Stagflation Phase I

- Page 355 and 356:

Case in Point: From the Challenging

- Page 357 and 358:

In the long run, real GDP moves to

- Page 359 and 360:

A worker’s reservation wage is li

- Page 361 and 362:

KEY TAKEAWAYS Two factors that can

- Page 363 and 364:

16.4 Review and Practice Summary Du

- Page 365 and 366:

NUMERICAL PROBLEMS 1. Here are annu

- Page 367 and 368:

The contraction in output that bega

- Page 369 and 370:

Figure 17.2 "Aggregate Demand and S

- Page 371 and 372:

Case in Point: Early Views on Stick

- Page 373 and 374:

The Kennedy administration also add

- Page 375 and 376:

changes in the money supply as the

- Page 377 and 378:

Two particularly controversial prop

- Page 379 and 380:

Case in Point: Tough Medicine Figur

- Page 381 and 382:

new direction damaged Mr. Carter po

- Page 383 and 384:

The sudden change in the relationsh

- Page 385 and 386:

Case in Point: Steering on a Diffic

- Page 387 and 388:

Summary We have surveyed the experi

- Page 389 and 390:

The United States is the richest la

- Page 391 and 392:

We have seen that the income distri

- Page 393 and 394:

were. The “intellectual wage gap

- Page 395 and 396:

Case in Point: Attitudes and Inequa

- Page 397 and 398:

Figure 18.4 Weighted Average Povert

- Page 399 and 400:

Figure 18.6 "The Demographics of Po

- Page 401 and 402:

Given a choice between cash and an

- Page 403 and 404:

Look at Figure 18.9 "Poor People an

- Page 405 and 406:

women having families, and reductio

- Page 407 and 408:

white men; in 2005, they were 75% o

- Page 409 and 410:

Case in Point: Early Intervention P

- Page 411 and 412:

CONCEPT PROBLEMS 1. Explain how ris

- Page 413 and 414:

for skilled workers and the market

- Page 415 and 416:

income countries in 2007. We should

- Page 417 and 418:

We can also see the results of poor

- Page 419 and 420:

HDI rank Country Human Development

- Page 421 and 422:

Case in Point: (Growth and Developm

- Page 423 and 424:

“At the end of each day, the worl

- Page 425 and 426:

Figure 19.7 Income Levels and Popul

- Page 427 and 428:

Case in Point: China Curtails Popul

- Page 429 and 430:

economic growth by making available

- Page 431 and 432:

notably Indonesia and Malaysia, the

- Page 433 and 434:

Summary Developing nations face a h

- Page 435 and 436:

The Economics of Karl Marx Marx is

- Page 437 and 438:

TRY IT! Briefly explain how each of

- Page 439 and 440:

crowded into the factory, are organ

- Page 441 and 442:

Although the Soviet Union was able

- Page 443 and 444:

Case in Point: Socialist Cartoons T

- Page 445 and 446:

The practical alternative to allowi

- Page 447 and 448:

Russia: An Uncertain Path to Reform

- Page 449 and 450:

TRY IT! Table 20.1 "Official Versus

- Page 451 and 452:

TRY IT! There is a shortage of cars

- Page 453 and 454:

Figure 21.1 Ski Club Revenues The s

- Page 455 and 456:

horizontal axis, measured between t

- Page 457 and 458:

As an example of a graph of a negat

- Page 459 and 460:

evenue curves unchanged. That is be

- Page 461 and 462:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Understand n

- Page 463 and 464:

Figure 21.14 Tangent Lines and the

- Page 465 and 466:

TRY IT! Consider the following curv

- Page 467 and 468:

the scaling of the vertical axis us

- Page 469 and 470:

Figure 21.22 Intended Academic Majo

- Page 471 and 472:

ANSWER TO TRY IT! Here are the time

- Page 473 and 474:

What do you think is the argument m

- Page 475 and 476:

Equation 22.14 The coefficient of r

- Page 477 and 478:

Figure 22.2 A Decrease in Autonomou

- Page 479:

NUMERICAL PROBLEMS 1. Suppose an ec