N ieman Reports - Nieman Foundation - Harvard University

N ieman Reports - Nieman Foundation - Harvard University

N ieman Reports - Nieman Foundation - Harvard University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Shattering Barriers<br />

OCCRP will not approve the story.<br />

Using this method is how I was able to<br />

publish several stories that otherwise<br />

I would not have been able to get to<br />

readers in Ukraine. After their initial<br />

publication abroad, these articles could<br />

appear in Ukrainian media as reprints<br />

of foreign news stories. This method<br />

is much safer for the publishers.<br />

My plan is to launch a similar<br />

investigative journalism project in<br />

Ukraine—and what I will do first<br />

is to use any funding we receive to<br />

make libel insurance available to local<br />

journalists. For now, a few of my<br />

Ukrainian colleagues joke that I have<br />

invented “offshore journalism.” I know<br />

they are actually happy for me. They<br />

understand that this is just a way to<br />

fight self-censorship. <br />

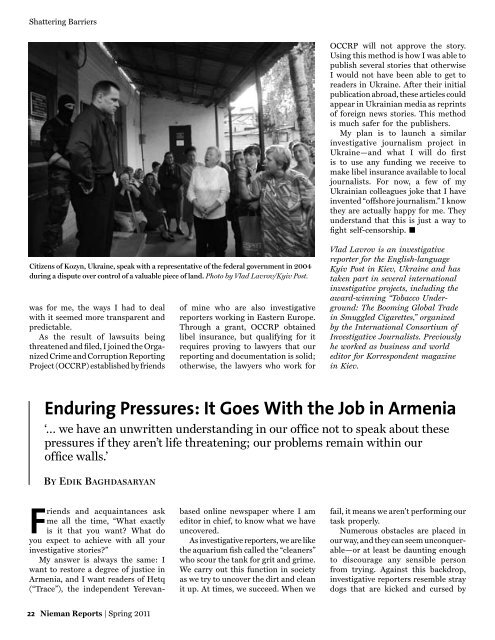

Citizens of Kozyn, Ukraine, speak with a representative of the federal government in 2004<br />

during a dispute over control of a valuable piece of land. Photo by Vlad Lavrov/Kyiv Post.<br />

was for me, the ways I had to deal<br />

with it seemed more transparent and<br />

predictable.<br />

As the result of lawsuits being<br />

threatened and filed, I joined the Organized<br />

Crime and Corruption Reporting<br />

Project (OCCRP) established by friends<br />

of mine who are also investigative<br />

reporters working in Eastern Europe.<br />

Through a grant, OCCRP obtained<br />

libel insurance, but qualifying for it<br />

requires proving to lawyers that our<br />

reporting and documentation is solid;<br />

otherwise, the lawyers who work for<br />

Vlad Lavrov is an investigative<br />

reporter for the English-language<br />

Kyiv Post in Kiev, Ukraine and has<br />

taken part in several international<br />

investigative projects, including the<br />

award-winning “Tobacco Underground:<br />

The Booming Global Trade<br />

in Smuggled Cigarettes,” organized<br />

by the International Consortium of<br />

Investigative Journalists. Previously<br />

he worked as business and world<br />

editor for Korrespondent magazine<br />

in Kiev.<br />

Enduring Pressures: It Goes With the Job in Armenia<br />

‘… we have an unwritten understanding in our office not to speak about these<br />

pressures if they aren’t life threatening; our problems remain within our<br />

office walls.’<br />

BY EDIK BAGHDASARYAN<br />

Friends and acquaintances ask<br />

me all the time, “What exactly<br />

is it that you want? What do<br />

you expect to achieve with all your<br />

investigative stories?”<br />

My answer is always the same: I<br />

want to restore a degree of justice in<br />

Armenia, and I want readers of Hetq<br />

(“Trace”), the independent Yerevanbased<br />

online newspaper where I am<br />

editor in chief, to know what we have<br />

uncovered.<br />

As investigative reporters, we are like<br />

the aquarium fish called the “cleaners”<br />

who scour the tank for grit and grime.<br />

We carry out this function in society<br />

as we try to uncover the dirt and clean<br />

it up. At times, we succeed. When we<br />

fail, it means we aren’t performing our<br />

task properly.<br />

Numerous obstacles are placed in<br />

our way, and they can seem unconquerable—or<br />

at least be daunting enough<br />

to discourage any sensible person<br />

from trying. Against this backdrop,<br />

investigative reporters resemble stray<br />

dogs that are kicked and cursed by<br />

22 N<strong>ieman</strong> <strong>Reports</strong> | Spring 2011