Executive summary and introduction.doc - Pockets - Distributed ...

Executive summary and introduction.doc - Pockets - Distributed ...

Executive summary and introduction.doc - Pockets - Distributed ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

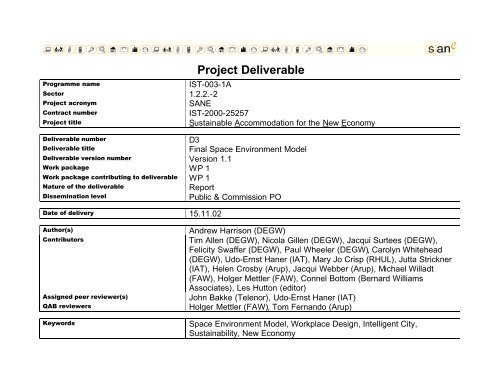

Project Deliverable<br />

Programme name<br />

IST-003-1A<br />

Sector 1.2.2.-2<br />

Project acronym<br />

SANE<br />

Contract number<br />

IST-2000-25257<br />

Project title<br />

Sustainable Accommodation for the New Economy<br />

Deliverable number<br />

Deliverable title<br />

Deliverable version number Version 1.1<br />

Work package WP 1<br />

Work package contributing to deliverable WP 1<br />

Nature of the deliverable<br />

Report<br />

Dissemination level<br />

Date of delivery 15.11.02<br />

D3<br />

Final Space Environment Model<br />

Public & Commission PO<br />

Author(s)<br />

Contributors<br />

Assigned peer reviewer(s)<br />

QAB reviewers<br />

Keywords<br />

Andrew Harrison (DEGW)<br />

Tim Allen (DEGW), Nicola Gillen (DEGW), Jacqui Surtees (DEGW),<br />

Felicity Swaffer (DEGW), Paul Wheeler (DEGW), Carolyn Whitehead<br />

(DEGW), Udo-Ernst Haner (IAT), Mary Jo Crisp (RHUL), Jutta Strickner<br />

(IAT), Helen Crosby (Arup), Jacqui Webber (Arup), Michael Willadt<br />

(FAW), Holger Mettler (FAW), Connel Bottom (Bernard Williams<br />

Associates), Les Hutton (editor)<br />

John Bakke (Telenor), Udo-Ernst Haner (IAT)<br />

Holger Mettler (FAW), Tom Fern<strong>and</strong>o (Arup)<br />

Space Environment Model, Workplace Design, Intelligent City,<br />

Sustainability, New Economy

SANE space environment model<br />

November 2002<br />

D3<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257

Contents<br />

Acknowledgements 1<br />

<strong>Executive</strong> <strong>summary</strong> 3<br />

Introduction 29<br />

The changing workplace 35<br />

1 Sustainable workplaces in the new economy 37<br />

Sustainability 37<br />

New ways of working 51<br />

The new economy 55<br />

Towards a space environment model 111<br />

4 The distributed workplace 113<br />

The intelligent city 113<br />

A distributed workplace model 118<br />

Initial space environment model 119<br />

5 SANE user research 125<br />

The business context 125<br />

Workplace strategies 126<br />

User reactions 131<br />

6 The space environment model 135<br />

Knowledge work activities – the layers of what we do 136<br />

Where we work in a technology-enabled world – the<br />

workscape 143<br />

Selecting appropriate workscapes 151<br />

2 The evolution of the office 65<br />

Basic office typologies 65<br />

The emergence of the differentiated workplace 71<br />

Extending the workplace 79<br />

3 Workplace evaluation 91<br />

Historical approaches 91<br />

Limitations of existing approaches 100<br />

Sustainability-grounded measures 106

A SANE strategy 167<br />

7 Creating a distributed workplace strategy 169<br />

Generic methodology 169<br />

Information <strong>and</strong> telecommunications<br />

methodology 180<br />

Human interaction methodology 188<br />

8 Implementing hybrid workscapes <strong>and</strong> distributed workplace<br />

strategies 195<br />

Organisational culture 196<br />

Knowledge work <strong>and</strong> corporate culture 204<br />

Workplace change management 207<br />

9 Costing workplace strategies – an evaluative framework 219<br />

Constructing the business case 219<br />

Preparation of space <strong>and</strong> cost models 222<br />

Prototype model results 234<br />

Sustainable work environments 239<br />

10 Design <strong>and</strong> the distributed workplace 241<br />

Requirements of the knowledge economy 242<br />

Quantitative building measures 247<br />

Building innovation 249<br />

11 The shared workplace 259<br />

The neighbourhood or project work centre 260<br />

The corporate centre 274<br />

Evaluating shared workplaces 281<br />

12 Sustainability metrics in the new workplace 289<br />

Measures of sustainability 289<br />

Applying measures of sustainability to the<br />

workplace 297<br />

Sustainability <strong>and</strong> the workplace strategy 301<br />

Appendices<br />

One: Glossary 311<br />

Two: Case studies 319<br />

Three: CSR framework 331<br />

Four: Sustainability indicators, systems <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ards 337<br />

References 349

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The SANE research consortium consists of:<br />

DEGW (lead consultant)<br />

Institut Cerda<br />

FAW<br />

IAT University of Stuttgart<br />

Ove Arup & Partners International<br />

Royal Holloway, University of London<br />

Telenor AS<br />

SANE is a research project in the European Commission’s Fifth<br />

Framework research programme. Within the Information Society <strong>and</strong><br />

Technologies section, SANE responds to Key Action II (New Methods of<br />

Work <strong>and</strong> Electronic Commerce). It addresses II.2 (Flexible Mobile <strong>and</strong><br />

Remote Working Methods <strong>and</strong> Tools) as a whole, with the primary results<br />

in II.2.1 (Sustainable Workplace Design).<br />

We would like to acknowledge the diverse contributions of all the SANE<br />

partners to the production of this deliverable. The earlier internal<br />

deliverables, the outputs from the other work packages, the consortium<br />

meetings <strong>and</strong> internal project communications throughout the project have<br />

all contributed greatly to the development of the concepts outlined in this<br />

<strong>doc</strong>ument.<br />

The objective of SANE is to enable space designers, technology<br />

developers <strong>and</strong> other professionals concerned with the workplace to move<br />

from a location centric to a location independent approach. SANE will<br />

focus on the use of new internet <strong>and</strong> mobile technology services for<br />

supporting networked communities to ensure compatible interaction styles<br />

for local, mobile <strong>and</strong> remote work area <strong>and</strong> group members.<br />

SANE IST-2000-25257 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

<strong>Executive</strong> <strong>summary</strong><br />

SANE is a research project in the European Commission’s Fifth<br />

Framework research programme. Within the Information Society <strong>and</strong><br />

Technologies section, SANE responds to Key Action II (New<br />

Methods of Work <strong>and</strong> Electronic Commerce). It addresses II.2<br />

(Flexible Mobile <strong>and</strong> Remote Working Methods <strong>and</strong> Tools) as a<br />

whole, with the primary results in II.2.1 (Sustainable Workplace<br />

Design).<br />

The space environment modelling work package (WP1) focuses<br />

on the architectural aspects of the human environment in<br />

organisational settings. In this deliverable, D3: the final SANE<br />

space environment model, the concepts developed within the three<br />

theoretical workpackages of the SANE project are fused into a<br />

conceptual model for generic methodology for describing the<br />

implementation of a distributed workplace project.<br />

By tightly aligning business strategy <strong>and</strong> processes with new work<br />

place design concepts <strong>and</strong> hybrid information spaces, organisations<br />

can deliver business advantage through improved workplace<br />

performance, increased productivity, new distributed services <strong>and</strong><br />

increased information exchange. SANE defines, develops,<br />

implements <strong>and</strong> manages a productive consulting strategy that<br />

integrates a business strategy with the processes, knowledge <strong>and</strong><br />

information about work place <strong>and</strong> technological implementation into a<br />

dynamic, efficient enterprise.<br />

THE CHANGING WORKPLACE<br />

During the last quarter of the twentieth century, awareness of the<br />

principles of sustainability has become a global phenomenon. The<br />

field of the built environment offers huge potential for abuse of the<br />

key principles involved in sustainability <strong>and</strong> this, coupled with an<br />

accelerated rate of change in the ways in which we work, imposes an<br />

urgent imperative for a clear <strong>and</strong> well-informed course of action.<br />

SUSTAINABILITY<br />

The broadest definitions of this relatively new term all agree on one<br />

key point: that however we use our world <strong>and</strong> its resources, we<br />

should preserve the ability of future generations to do the same. This<br />

concept, although long a principle of various native American <strong>and</strong><br />

other pre-industrial societies, first found broad expression in the<br />

words of Thomas Jefferson:<br />

‘Then I say the earth belongs to each … generation during its course, fully<br />

<strong>and</strong> in its own right, no generation can contract debts greater than may be<br />

paid during the course of its own existence’. 1<br />

This principle was picked up in the definition set out in the 1987<br />

Brundtl<strong>and</strong> Commission 2 Report – ‘Our Common Future’, where<br />

Sustainability is defined in terms of development 3 as follows:<br />

1 September 6, 1789; quoted on the website of the Centre of Excellence for<br />

Sustainable Development – (http://www.sustainable.doe.gov/overview/definitions)<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257 3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

‘Sustainable development meets the needs of the present without<br />

compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’<br />

on the economy <strong>and</strong> economic development as central to achieving<br />

sustainability, seeking to overturn the conventional wisdom that<br />

economic development can only take place at the expense of the<br />

environment:<br />

The Brundtl<strong>and</strong> Report emphasises the need for economic<br />

development to take place in a manner that meets the basic needs of<br />

the world's poor, <strong>and</strong> approaches economics with a view to the<br />

impact of human activity on the surrounding environment.<br />

This definition established the benchmark on which all subsequent<br />

definitions have been based. Since then definitions have embodied a<br />

wide variety of foci, including: maintaining intergenerational welfare;<br />

maintaining the existence of the human species; sustaining the<br />

productivity of economic systems; maintaining biodiversity; <strong>and</strong><br />

maintaining evolutionary potential. 4 Most have retained the emphasis<br />

2 The World Commission on Environment <strong>and</strong> Development was created as a<br />

consequence of General Assembly resolution 38/161 adopted at the 38th Session<br />

of the United Nations in autumn 1983. That resolution called upon the Secretary-<br />

General to appoint the Chairman <strong>and</strong> Vice-Chairman of the Commission <strong>and</strong> in<br />

turn directed them to jointly appoint the remaining members, at least half of whom<br />

were to be selected from the developing world. The Secretary General appointed<br />

Mrs. Gro Harlem Brundtl<strong>and</strong> of Norway, then leader of the Norwegian Labour<br />

Party, as Chairman <strong>and</strong> Dr. Mansour Khalid, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs<br />

from Sudan, as Vice-Chairman.<br />

‘Sustainability is the [emerging] <strong>doc</strong>trine that economic growth <strong>and</strong><br />

development must take place, <strong>and</strong> be maintained over time, within the limits<br />

set by ecology in the broadest sense - by the interrelations of human beings<br />

<strong>and</strong> their works, the biosphere <strong>and</strong> the physical <strong>and</strong> chemical laws that<br />

govern it … It follows that environmental protection <strong>and</strong> economic<br />

development are complementary rather than antagonistic processes.’ 5<br />

Definitions have also sought to emphasise the need for a holistic<br />

approach to the concept exp<strong>and</strong>ing the application of sustainability<br />

beyond the realms of the economic to describe it in terms of natural<br />

earth processes:<br />

‘Sustainable development means improving the quality of life while living<br />

within the carrying capacity of supporting systems’ 6 ;<br />

‘Sustainability refers to the ability of a society, ecosystem, or any such<br />

ongoing system to continue functioning into the indefinite future without<br />

being forced into decline through exhaustion … of key resources’. 7<br />

3 N.B. In the literature ‘Sustainability’ <strong>and</strong> ‘Sustainable Development’ are often used<br />

interchangeably – sustainability implies a process, which can be referred to as<br />

development.<br />

4 Melinda Kane, ‘Sustainability Concepts: From Theory to Practice’, in Köhn etc<br />

5 William D. Ruckelshaus, ‘Toward a Sustainable World’, Scientific American,<br />

September 1989.<br />

6 World Wide Fund for Nature, from the DETR website:<br />

http://www.detr.gov.uk/regeneration/sustainable/guide/2.htm<br />

4 SANE IST-2000-25257

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

In particular the definition has been exp<strong>and</strong>ed to encompass three<br />

key aspects involving the physical environment, social organisation<br />

<strong>and</strong> economic processes:<br />

‘'sustainable development' is development that delivers basic environmental,<br />

social, <strong>and</strong> economic services to all residents of a community without<br />

threatening the viability of the natural, built, <strong>and</strong> social systems upon which<br />

the delivery of these services depends’. 8<br />

NEW WAYS OF WORKING<br />

Current best practice in office design has begun to embrace a variety<br />

of architectural <strong>and</strong> construction solutions to the problem of creating<br />

more energy efficient <strong>and</strong> environmentally comfortable office<br />

buildings. However, there is little attempt to question the prevailing<br />

workplace accommodation paradigm. In this paradigm – a<br />

descendant of the planning principles formulated under the Congrés<br />

International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) <strong>and</strong> espoused by<br />

planners <strong>and</strong> architects ever since – office workers are employed in<br />

dedicated office buildings, often remote from other urban <strong>and</strong> social<br />

functions.<br />

Within this paradigm there have been significant advances in terms<br />

of creating individual buildings that are more ‘environmentally<br />

sustainable’, in the sense that they consume less energy <strong>and</strong><br />

produce less waste per measure of office space created. There are<br />

two main aspects to this: the first involves the construction process;<br />

the second involves the building itself.<br />

The construction process has been the focus of attempts to reduce<br />

the amount of material <strong>and</strong> energy consumed in building erection,<br />

through, for example: increased pre-fabrication to reduce<br />

construction time <strong>and</strong> material waste; reduction in water<br />

consumption; reduction in transport distances <strong>and</strong> costs; use of selffinished<br />

materials; <strong>and</strong> recycling of construction waste. In short,<br />

those responsible for building delivery should be driven by what<br />

Taylor <strong>and</strong> Twinn have simply termed ‘good neighbourliness’. 9<br />

In terms of the building, key ideas that have contributed to its<br />

environmental sustainability include thermal mass; increased passive<br />

ventilation or simple mechanical ventilation; passive cooling;<br />

reduction of internal heat gains; solar control, glare control <strong>and</strong><br />

orientation; ease of operation; increased user interface; <strong>and</strong> the<br />

<strong>introduction</strong> of monitoring programmes.<br />

7 Robert Gilman, President of Context Institute, quoted on the website of the Centre of<br />

Excellence for Sustainable Development –<br />

(http://www.sustainable.doe.gov/overview/definitions)<br />

Environmental sustainability, as expressed in these aspects, focuses<br />

on the interdependence of structure, environmental services <strong>and</strong><br />

building fabric. It is taken to mean ecologically responsive, <strong>and</strong><br />

8 International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives from the DETR website:<br />

http://www.detr.gov.uk/regeneration/sustainable/guide/2 .htm<br />

9 Bill Taylor <strong>and</strong> Chris Twinn – ‘Sustainable Design as an Evolutionary Process’<br />

presentation at Cool Space.<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

responsible, solutions to workplace design. This approach should<br />

result in higher quality workplaces, <strong>and</strong> therefore in increased<br />

productivity, if one accepts that environmentally benign buildings are<br />

usually better liked by their users. 10<br />

In this way, to some extent, the environmentally sustainable office<br />

building becomes part of the wider agenda embracing social <strong>and</strong><br />

economic sustainability, if measured in terms of user satisfaction <strong>and</strong><br />

productivity. However, social sustainability requires that the building<br />

works both for its users inside, <strong>and</strong> is responsible to others into<br />

whose broader community it fits – i.e. what does the building give<br />

back to the city<br />

both a challenge <strong>and</strong> an opportunity. According to a report published<br />

by Information Society Technologies 11 , the sustainable workplace<br />

will have positive net business benefits; positive net societal impacts<br />

(both internally in terms of human resources <strong>and</strong> externally on wider<br />

society); <strong>and</strong> low net environmental impact (especially through<br />

material <strong>and</strong> energy consumption).<br />

Rather than referring to the workplace, we should perhaps begin to<br />

talk about ‘work systems’ or ‘work environments’. Any realistic<br />

attempt to create sustainable office accommodation must take a<br />

broader view than the design of individual buildings. It should be<br />

asking some of the following questions:<br />

True sustainability, however, embodies far more than simply the<br />

building <strong>and</strong> its construction – it involves its incorporation into the<br />

wider environment: the integration with local transport systems; the<br />

opportunity for mixed use communities; the opportunity to walk to<br />

work; <strong>and</strong> the opportunity for developments to contribute to rather<br />

than detract from the local community. Increasingly technology will<br />

play a part in the creation of these environments, enabling lean<br />

construction <strong>and</strong> flexible use.<br />

What is in fact needed is a redefinition of the term ‘workplace’. It<br />

needs to be broadened from the narrow focus on the office building,<br />

to incorporate the various work environments embraced by the ‘new<br />

economy’ <strong>and</strong> ‘new ways of working’. This, of course, represents<br />

10 Rab Bennetts – ‘Evolution <strong>and</strong> Significant Linkages over Two Decades’;<br />

presentation at Cool Space.<br />

• What is a more sustainable way of work, of operating an<br />

economy<br />

• What is the nature of the sustainable working environment<br />

• How should we house office workers – in dedicated buildings or<br />

elsewhere<br />

• Where should these working environments be located<br />

• How should people move <strong>and</strong> communicate between working<br />

environments, <strong>and</strong> between these <strong>and</strong> other environments<br />

• What elements should be incorporated into the sustainable<br />

working environment, both to increase productivity <strong>and</strong> efficiency,<br />

<strong>and</strong> to reduce consumption<br />

What seems to be common to all definitions of sustainability is a<br />

concern that we preserve for future generations similar opportunities,<br />

11 Information Society Technologies – Sustainable Workplaces in a Global Information<br />

Society<br />

6 SANE IST-2000-25257

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

in terms of quality of life <strong>and</strong> the potential to exploit the world’s<br />

resources, to those we enjoy today. Most of the literature places the<br />

emphasis on economic development, crucially seeing this as<br />

complementary, rather than in opposition, to environmental<br />

preservation. But any approach to the sustainability agenda must be<br />

holistic, embracing all its various aspects. The usual divisions into<br />

environmental, economic <strong>and</strong> social sustainability falsely attempt to<br />

represent mutually indivisible areas of concern. Achieving<br />

sustainability should be seen as a dynamic process, rather than an<br />

end in itself. It should be seen as an attitude, rather than a definable<br />

set of goals. If human society <strong>and</strong> the earth are seen as a single<br />

system, then the single most important factor will be the capacity of<br />

this system to absorb change <strong>and</strong> to evolve. Diversity is a key factor<br />

in safeguarding this potential.<br />

There are several broad themes that emerge among the various<br />

strategies for tackling the sustainability agenda. Principle among<br />

these is the inefficiency of the existing market frameworks, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

need for an adjustment both of these <strong>and</strong> of the driving economic<br />

trend of consumption. Rather than valuing products, we should be<br />

valuing ideas <strong>and</strong> human capital. Technological progress is seen as<br />

offering positive benefits through economic growth <strong>and</strong><br />

dematerialisation of products <strong>and</strong> processes.<br />

This brings with it the so-called ‘rebound effect’, in which such<br />

progress tends to have benefit at the micro level, but at the macro<br />

scale to be negative. Technological progress will therefore only be of<br />

lasting benefit within appropriate social <strong>and</strong> economic frameworks,<br />

governing the directions it takes. New global societal structures are<br />

needed, creating a culture of, <strong>and</strong> framework for, mutual global<br />

responsibility. The city emerges as the key site for achieving this end,<br />

due to its position as the site of advanced social <strong>and</strong> economic<br />

interaction.<br />

In terms of the workplace, much useful work has been done towards<br />

the creation of more environmentally sustainable offices, but the<br />

principle requirement in achieving sustainability here will be a<br />

redefinition of the workplace, <strong>and</strong> a re-evaluation of its requirements<br />

<strong>and</strong> constituent parts.<br />

WORKPLACE EVALUATION<br />

Any method of evaluation will reflect current concerns <strong>and</strong> ways of<br />

thinking about ‘the workplace’ among organisations <strong>and</strong> in the wider<br />

society – <strong>and</strong> the ideas underlying past <strong>and</strong> current ways of<br />

evaluation may provide insights into the changing views of what<br />

constitutes a workplace <strong>and</strong> how it might fit into the broader social<br />

context. In the context of the SANE project, an assessment of<br />

evaluation techniques is invaluable because such techniques<br />

themselves can change the way society thinks about what is being<br />

measured. It is hoped that a discussion within the SANE project of<br />

the kinds of workplace measures that ought to be developed might<br />

contribute to advancing thought within the business <strong>and</strong><br />

organisational community about what workplaces are, could <strong>and</strong><br />

should be, <strong>and</strong> enable the countries of the European Union to be at<br />

the forefront in using ‘workplaces’ (in the broadest possible meaning)<br />

to promote economic, social <strong>and</strong> environmental well-being.<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257 7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

The history of workplace evaluation is closely linked with the history<br />

of workplace design. Broadly speaking, offices prior to the 1960s <strong>and</strong><br />

1970s were based on ideas borrowed from industry, such as the<br />

model of the production line as first implemented in Ford’s car plants<br />

early in the twentieth century. This involved the ‘division of labour’:<br />

the breaking down of complex tasks into a number of simple subtasks.<br />

Work moves between individuals each repeating a single,<br />

specialised sub-task (rather than the alternative approach of one<br />

individual seeing an entire process through from start to finish,<br />

carrying out all the sub-tasks involved). Thus, the key features of the<br />

Fordist approach to workplace design are the division of labour <strong>and</strong><br />

an emphasis on the efficient flow of work.<br />

Ford’s approach owed much to the ‘scientific management’ ideas<br />

developed in the late nineteenth century by F.W. Taylor. Taylor’s<br />

basic assumption was that an empirical, scientific approach to the<br />

study of work would yield benefits in terms of productivity; he<br />

believed that by measuring how people carry out a task, ways of<br />

making the process faster or better would become evident, <strong>and</strong> that<br />

this focus on increasing the efficiency of the individual task would<br />

improve the overall, large-scale process.<br />

In keeping with the Taylorist approach, the workplace evaluation<br />

measures prevalent during the first six decades of the twentieth<br />

century adopted an overtly scientific approach, investigating one<br />

factor at a time using the classic experimental method 12 .<br />

12 Within the experimental method a single factor of interest is systematically varied<br />

by the experimenter, while all other conditions are held constant, <strong>and</strong> the effect on<br />

some output of interest is measured.<br />

During the 1970s <strong>and</strong> 1980s, the exp<strong>and</strong>ing economy <strong>and</strong> general<br />

business climate laid even greater emphasis on efficiency as the<br />

post-war boom ended. At the same time, the increasing focus on<br />

quantitative approaches in many social sciences led to renewed<br />

interest in workplace evaluation, <strong>and</strong> the development of the<br />

discipline of environmental psychology gave a fresh impetus to the<br />

idea of measuring the effects of the workplace. During these<br />

decades, an increasing number of studies were undertaken with the<br />

aim of investigating the efficiency of workplaces.<br />

A worldwide recession in the late 1980s had a profound effect on<br />

European business. Companies cut staff drastically (downsizing) <strong>and</strong><br />

this meant that they had surplus space available. This offered<br />

another opportunity for cost savings, as companies rid themselves of<br />

surplus buildings. This sometimes involved rationalisation of the use<br />

of their remaining buildings, <strong>and</strong> continuing concern with how<br />

efficiently they were using the space they retained.<br />

This recession was the high-water mark for the focus on ‘efficiency’<br />

in workplace measures. As companies came out of the recession<br />

‘leaner <strong>and</strong> meaner’, organisations began to realise that an emphasis<br />

on ‘efficiency’ in the workplace was not necessarily enough; indeed,<br />

it might be pushing the organisation in the opposite direction to that<br />

of better profits <strong>and</strong> more effective operations as a whole. The<br />

intense focus on efficiency <strong>and</strong> cost saving had been, for many<br />

organisations, counter-productive. There was an increasing<br />

recognition of the importance to the organisation of the knowledge<br />

about it which staff carried in their heads. Thus, the focus on<br />

efficiency had been masking the need to focus on some broader<br />

8 SANE IST-2000-25257

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

measure of the contribution of people’s work to the organisation as a<br />

whole. Duffy (1997) sums up this distinction succinctly: from<br />

concentrating on efficiency – ‘doing things right’, the focus switched<br />

to effectiveness – ‘doing the right thing’, adding value to the<br />

enterprise.<br />

What exactly do we mean by ‘effectiveness’ Duffy (1997) describes<br />

it as a focus on:<br />

• increasing value<br />

• using space to its full potential<br />

• having the right range of work settings to match the different<br />

types of work carried out<br />

• making the most of people.<br />

This focus on effectiveness reflects many changes in organisational<br />

style <strong>and</strong> priorities over the last decade or so. There has been a<br />

huge increase in the importance of horizontal interaction across<br />

organisational divisions, so that the value of interaction among staff<br />

members is now recognised much more clearly<br />

Also, as Duffy (1997) points out, occupancy costs are a relatively<br />

small proportion of the overall costs of employing someone. Focusing<br />

simply on occupancy costs is unlikely to yield significant cost savings<br />

<strong>and</strong> these may easily be outweighed by additional staff costs as key<br />

employees lose motivation or even leave the organisation. A focus<br />

on how ‘efficient’ the workspace is will not offer the best ‘leverage’ for<br />

an organisation – it is the wrong place on which to focus attention<br />

<strong>and</strong> to carry out cost-cutting exercises. It became clear that the focus<br />

should be on helping staff to work as effectively as possible.<br />

Given this change of focus towards looking at the productivity of the<br />

organisation as a whole in its widest sense, rather than space<br />

efficiency, a different set of factors become important, <strong>and</strong> thus, a<br />

different set of workplace evaluation tools are needed. However, it is<br />

much more difficult to measure the ‘effectiveness’ of an organisation<br />

than to measure the ‘efficiency’ of office space.<br />

Contemporary management thinking departs substantially from the<br />

rigours of prescribed tasks <strong>and</strong> hierarchically -driven work processes,<br />

relying instead on highly-motivated individuals who are enabled by<br />

technology to have a high degree of autonomy <strong>and</strong> use face-to-face<br />

interaction to increase the richness of their business transactions.<br />

The kind of workplace that truly supports this kind of business<br />

environment is very different from the more traditional approach to<br />

office design discussed earlier. The office thus becomes a place for<br />

stimulating intellect <strong>and</strong> creativity. The focus moves towards enabling<br />

the knowledge worker to perform at their best.<br />

The history of workplace evaluation can then be summarised as<br />

moving from a focus on efficiency to a focus on effectiveness. This<br />

shift has taken place at the same time as a number of other changes<br />

in office work, with the general aim of giving more autonomy to<br />

knowledge workers <strong>and</strong> to increase the interaction between them. A<br />

report published by the UK-based Industrial Society 13 identifies these<br />

13 Nathan & Doyle 2002<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257 9

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

changes more specifically, <strong>and</strong> their effect on the design <strong>and</strong> layout<br />

of offices:<br />

• The rise in prevalence of ‘nomadic workers’ (who have multiple<br />

workspaces, including some outside the office).<br />

• Increasing flexibility of people’s workstyles when working within<br />

the office (people move from setting to setting as appropriate,<br />

often having no fixed workspace that ‘belongs’ to them; furniture<br />

is mobile <strong>and</strong> spaces are reconfigured for group <strong>and</strong> individual<br />

working; working hours are varied).<br />

• The office is being reconfigured as a forum for ideas exchange,<br />

community space, team space, <strong>and</strong> a drop-in place for mobile<br />

workers – as well as a catalyst for wider cultural <strong>and</strong><br />

organisational change.<br />

If the focus on efficiency was too narrow, concentrating attention on<br />

short-term savings in space costs rather than the long-term benefits<br />

of a more effective organisation, is the more recent focus on<br />

effectiveness the final answer to the question of where organisations<br />

should focus their attention regarding the space they provide for their<br />

office staff Is the focus on effectiveness itself limiting in any way,<br />

<strong>and</strong> are there any other factors that we should be considering when<br />

looking at sustainable accommodation for organisations in the new<br />

economy<br />

The limitations of the effectiveness approach can best be borne out<br />

by a consideration of three factors:<br />

• the tools currently used to evaluate effectiveness<br />

• the success or otherwise of workspaces designed around the<br />

concept of effectiveness, generally termed ‘new ways of working’<br />

• the current environmental, social, cultural <strong>and</strong> economic climate<br />

within which organisations operate.<br />

There is no clear, categorical break between the idea that<br />

workplaces should be considered in terms of effectiveness (‘doing<br />

the right things’) <strong>and</strong> the ideas of workplace sustainability. The latter<br />

is merely going further, making more explicit, <strong>and</strong> thinking longerterm<br />

into the future about the goals that were implicit in the concept<br />

of the ‘effective workplace’. To be effective in the longer term,<br />

workplaces must contribute to the health <strong>and</strong> well-being not only of<br />

the organisation but of its staff, its business colleagues (clients,<br />

suppliers <strong>and</strong> business partners) <strong>and</strong> the wider economic <strong>and</strong> social<br />

environment.<br />

Two currently-accepted though relatively new approaches to<br />

measurement, Corporate Social Responsibility <strong>and</strong> Triple Bottom<br />

Line Accounting, begin to address issues of sustainability. Corporate<br />

Social Responsibility (CSR) represents those activities that are<br />

focused on creating <strong>and</strong> sustaining social, human <strong>and</strong> environmental<br />

capital within the context of an organisation’s economic activities.<br />

CSR reflects the increasing requirement by society that companies<br />

actively engage with employees <strong>and</strong> the communities in which they<br />

operate by going beyond regulatory compliance. Triple Bottom Line<br />

Accounting (TBLA) is the practice of accounting for those impacts on<br />

the social <strong>and</strong> natural environment that are incurred as a result of<br />

economic activities undertaken by a company. By measuring <strong>and</strong><br />

reporting on activities that are undertaken, a company formalises<br />

10 SANE IST-2000-25257

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

their commitment to instituting action plans that support stated<br />

policies, <strong>and</strong> are able to convey this commitment to stakeholders in a<br />

verifiable manner.<br />

In order to adopt this more holistic perspective – the perspective of<br />

an organism/organisation in an ecological niche within a wider<br />

environment, where the organism <strong>and</strong> environment are mutually<br />

sustaining – we must develop a space environment model applicable<br />

to an increasingly complex <strong>and</strong> disaggregated workscape.<br />

TOWARDS A SPACE ENVIRONMENT MODEL<br />

The 1990s has seen a revolution in the way that space <strong>and</strong> time are<br />

used in leading organisations. New ways of working have allowed<br />

many organisations to integrate the physical work environment into<br />

the business process, to increase density of occupation within office<br />

buildings while at the same time creating effective work environments<br />

that encourage interaction <strong>and</strong> communications.<br />

The next decade will see even greater challenges: both at the level of<br />

the individual trying to use the scarce resource of time more<br />

effectively <strong>and</strong> at the level of the organisation trying to manage a<br />

dispersed workforce while creating the spirit <strong>and</strong> teamwork<br />

necessary for organisations to continue to generate new ideas <strong>and</strong><br />

thrive. Increasingly organisations will move outside of the physical<br />

container of their own buildings into larger organisational networks<br />

across cities, countries, the region or the world.<br />

Once again information technology has played an essential role in<br />

the transformation, allowing forward thinking organisations to<br />

integrate a wider range of urban work settings into their corporate<br />

workspace. The need for building or space ownership becomes less<br />

significant as space is purchased on dem<strong>and</strong>, on an hourly, daily, or<br />

monthly basis or as non owned spaces such as hotels, airport<br />

lounges <strong>and</strong> clubs become a st<strong>and</strong>ard part of the working week. The<br />

city is the office.<br />

With distributed workforces only accessing buildings periodically the<br />

role of buildings is shifting dramatically. Work can take place<br />

anywhere so why should someone come to the office The office is<br />

seen as an opportunity to express the culture <strong>and</strong> reinforce the<br />

values <strong>and</strong> beliefs of an organisation. The physical work environment<br />

<strong>and</strong> the opportunities it provides for interaction <strong>and</strong> collaboration aid<br />

knowledge transfer <strong>and</strong> communication <strong>and</strong> will form the<br />

infrastructure for learning organisations.<br />

In 2000, DEGW developed a distributed workplace model - the basis<br />

for much of the SANE research <strong>and</strong> the predecessor of the eventual<br />

SANE space environment model. This model attempted to<br />

incorporate the increasing congruence between physical <strong>and</strong> virtual<br />

work environments, acknowledging the impact that information <strong>and</strong><br />

communications technologies have had on the work process of most<br />

individuals <strong>and</strong> organisations.<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257 11

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

THE DISTRIBUTED WORKPLACE<br />

The distributed workplace model developed by DEGW assumes<br />

radical changes in both the supply <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> sides of the building<br />

procurement model. On the supply side of the equation developers<br />

will increasingly realise that increased profits will result from thinking<br />

of buildings more in terms of the opportunity to deliver high value<br />

added services on a global basis to a customer base rather than as a<br />

simple passive investment vehicle.<br />

From the users’ perspective there is increasing interest in the<br />

provision of global solutions that provide flexibility <strong>and</strong> break down<br />

the old barriers between real estate provisions, building operation<br />

<strong>and</strong> the provision of business services.<br />

The role that buildings are playing in many organisations is also<br />

changing. Historically buildings have often provided a way of<br />

demonstrating organisational wealth, power <strong>and</strong> stability. The solid<br />

19 th century bank <strong>and</strong> insurance headquarters buildings in the UK<br />

<strong>and</strong> the 20 th century drive for taller <strong>and</strong> taller office buildings, often in<br />

the absence of a sound financial or real estate case for them, are<br />

both demonstrations of this.<br />

With distributed workforces only accessing buildings periodically the<br />

role of buildings is shifting dramatically. Work can take place<br />

anywhere so why should some-one come to the office The office is<br />

seen as an opportunity to express the culture <strong>and</strong> reinforce the<br />

values <strong>and</strong> beliefs of an organisation.<br />

The distributed workplace model also incorporates the increasing<br />

congruence between physical <strong>and</strong> virtual work environments,<br />

acknowledging the impact that information <strong>and</strong> communications<br />

technologies have had on the work process of most individuals <strong>and</strong><br />

organisations. The model also examines the continuum between<br />

public <strong>and</strong> private space <strong>and</strong> produce novel solutions to their<br />

integration into work places. The workplace is divided into three<br />

conceptual categories according to the degree of privacy <strong>and</strong><br />

accessibility they offer. The three categories of place used in the<br />

model are “public”, “privileged” <strong>and</strong> “private”.<br />

Each of these ‘places’ is composed of a number of different types of<br />

work settings, the relative proportion of each forming the character of<br />

the space. Public space is predominately suited for informal<br />

interaction <strong>and</strong> touchdown working for relatively short periods of time.<br />

Privileged space supports collaborative project team <strong>and</strong> meeting<br />

spaces as well as providing space for concentrated individual work.<br />

Private space also contains both individual <strong>and</strong> collaborative work<br />

settings but with a greater emphasis on privacy <strong>and</strong> confidentiality,<br />

with defined space boundaries <strong>and</strong> security.<br />

12 SANE IST-2000-25257

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

Knowledge systems<br />

e.g. VPN,<br />

corporate intranet<br />

Extranet sites<br />

Knowledge communities<br />

e.g. collaborative virtual<br />

environments, project<br />

extranets, video conference<br />

Internet sites<br />

e.g. information<br />

sources,<br />

chat rooms,<br />

©DEGW 2001<br />

Virtual<br />

Physical<br />

Private<br />

• Protected access<br />

• Individual or collaborative workspace<br />

Privileged<br />

• Invited access<br />

• Collaborative project <strong>and</strong> meeting space<br />

Public<br />

•Open access<br />

•Informal interaction <strong>and</strong> workspace<br />

e.g. serviced offices,<br />

incubator space,<br />

home working<br />

e.g. clubs,<br />

airport<br />

lounges,<br />

e.g. cafes,<br />

hotel lobbies,<br />

airport terminals<br />

Filters or<br />

boundaries<br />

Filters or<br />

boundaries<br />

is restricted to members of the organisation <strong>and</strong> the value of the<br />

organisation is related to the contents of this virtual space – the<br />

customer databases, the descriptions of processes <strong>and</strong> project<br />

histories.<br />

When designing accommodation strategies organisations will<br />

increasingly need to consider how the virtual work environments will<br />

be able to support distributed physical environments <strong>and</strong> how the<br />

virtual environments can contribute to the development of<br />

organisational culture <strong>and</strong> a sense of community when the staff<br />

spend little or no time in ‘owned’ facilities.<br />

FIGURE I. SPACE ENVIRONMENT MODEL - HYBRID WORKSCAPES<br />

Each of the physical work environments has a parallel virtual<br />

environment that shares some of the same characteristics. The<br />

virtual equivalent of the public workplace is the internet where<br />

access is open to all <strong>and</strong> behaviour is relatively ‘unmanaged’. The<br />

equivalents of the privileged workplace are extranets where<br />

communities of interest use the internet to communicate <strong>and</strong> as an<br />

information resource membership.<br />

There are restrictions to entry into a knowledge community (such as<br />

registration or membership by invitation only) <strong>and</strong> membership has<br />

obligations <strong>and</strong> responsibilities attached, perhaps in terms of<br />

contributing material or communicating with other members. The<br />

virtual equivalents of the private workplace are intranets, the private<br />

knowledge systems belonging to an individual organisation that<br />

contain the organisation’s intellectual property. Access to the Intranet<br />

An organisation could choose to locate the Public, Privileged <strong>and</strong><br />

Private workplaces within a single building <strong>and</strong> location. In many<br />

ways the rich mix of work settings provided in New Ways of Working<br />

implementations could be said to already do this. In the diagram<br />

below this type of combined work environment is referred to as<br />

‘‘Office is the City’. All workspace is owned by the organisation <strong>and</strong><br />

is occupied solely by then. Zoning within the building is often used to<br />

reinforce culture <strong>and</strong> community <strong>and</strong> urban metaphors such as<br />

‘neighbourhood’, ‘village’ <strong>and</strong> ‘street’ may be used to describe these<br />

zones.<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257 13

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

Owned space<br />

Shared space<br />

©DEGW 2001<br />

‘Office is the city’<br />

Single location,<br />

owned space<br />

Private<br />

Privileged<br />

Public<br />

Dispersed<br />

organization<br />

Multiple locations,<br />

owned space<br />

Private<br />

Privileged<br />

Public<br />

Figurehead<br />

organization<br />

Multiple locations,<br />

owned & shared spaces<br />

Private<br />

Multiple locations<br />

‘Owned’ spaces ‘Owned’ <strong>and</strong> public<br />

spaces<br />

Owned spaces for all Owned spaces<br />

activities<br />

Public<br />

for core activities<br />

Use of city locationsUse of city spaces<br />

to reinforce culture <strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> facilities for<br />

community<br />

Privileged<br />

‘City is the office’<br />

Multiple locations,<br />

shared spaces<br />

•<br />

Private<br />

•<br />

Privileged<br />

Public<br />

Increased use of distributed,shared workplaces<br />

Move from fixed to variable costs<br />

FIGURE 2. PROPERTY STRATEGIES FOR DISPERSED ORGANISATIONS<br />

As the level of remote working increases in an organisation it may<br />

not be desirable to house all types of workplace in the same location.<br />

Distributing workplaces around the city may allow staff to reduce the<br />

amount of commuting they need to do <strong>and</strong> allow the organisation to<br />

start using the attributes of the city to reinforce organisational culture<br />

<strong>and</strong> community. For example an organisation that wants to be<br />

thought of as innovative <strong>and</strong> trendy could choose to locate drop-in<br />

work centres in downtown retail/ leisure area such as Soho in<br />

London or Chelsea in New York while the bulk of their workplace<br />

could be in more traditional business locations. In the diagram above<br />

this property strategy is described as ‘dispersed.’<br />

Organisations are increasingly incorporating semi-public spaces such<br />

as hotels, serviced office centres, airport lounges <strong>and</strong> cafes into their<br />

work environments. It is possible that this trend will continue to the<br />

point where the only spaces actually owned by the organisation are<br />

the Private Workplaces including such things as Headquarters<br />

Buildings, Training <strong>and</strong> IT Centres. All other space could be provided<br />

by outside organisations on a flexible, ‘as used’ basis as well as<br />

many of the business support services. This type of real-estate<br />

strategy is described as ‘figurehead’ in the property strategy<br />

diagram above.<br />

If this move away from owned organisational space is taken to its<br />

extreme it is possible to envisage a completely virtual organisation<br />

where virtual work environments are used to house the<br />

organisation’s knowledge <strong>and</strong> information resources <strong>and</strong> all physical<br />

work takes place in either individually owned space (for example,<br />

staff working at home) or in shared work environments booked on an<br />

‘as-needed’ basis. In the diagram above this is described as ‘City is<br />

the Office.’ If this strategy is adopted by an organisation issues<br />

relatively to training <strong>and</strong> knowledge transfer, use of ICT to support<br />

the work process, management of distributed work teams <strong>and</strong><br />

informal interaction <strong>and</strong> team building will need to be carefully<br />

thought through.<br />

14 SANE IST-2000-25257

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

The <strong>introduction</strong> of a distributed workplace model potentially has both<br />

efficiency <strong>and</strong> effectiveness benefits that can work at the level of the<br />

individual, the organisation <strong>and</strong> the City. The distributed workplace<br />

model suggests that workspace in the future will be broken down into<br />

smaller units distributed across the city, including both suburban<br />

(close to home) <strong>and</strong> urban (close to clients) space.<br />

Smaller units of space can more easily be incorporated into the<br />

existing city fabric <strong>and</strong>, when combined with new methods of<br />

delivering both voice <strong>and</strong> data c ommunications, these smaller units<br />

may be accommodated within old or previously obsolete buildings in<br />

downtown areas. Opportunities are therefore provided for<br />

regenerating existing city districts to provide homes for New<br />

Economy companies.<br />

The re-use of buildings contributes to sustainability in terms of<br />

avoiding the construction of new buildings (materials <strong>and</strong> energy)<br />

<strong>and</strong> in the maintenance <strong>and</strong> support of existing communities.<br />

Remote working, whether at home or at neighbourhood work centres<br />

(café/ club type space) aids sustainability by improving the quality of<br />

life for individuals (reduced commuting time) <strong>and</strong> by the reduction of<br />

energy consumption.<br />

The increased use of shared space has economic implications for the<br />

organisations concerned. Buying space on an ‘as needed’ basis<br />

rather than by committing to long term leases allows organisations to<br />

move from a fixed cost structure to a more variable, freeing up capital<br />

to be invested in developing the business rather than just housing the<br />

existing business.<br />

As well as providing re-use <strong>and</strong> regeneration opportunities across the<br />

whole city a distributed work strategy also offers opportunities to<br />

specific cultural <strong>and</strong> historic facilities <strong>and</strong> areas that can attract<br />

organisations who want to use these cultural facilities to reinforce<br />

their organisational culture in the absence of their own buildings.<br />

At the level of the individual, distributed working allows more control<br />

over the use of time, with reduced commuting <strong>and</strong> an ability to match<br />

the work environment to the tasks required: to use visits to the office<br />

to meet with colleagues <strong>and</strong> work with project teams <strong>and</strong> use a range<br />

of other locations for concentrated individual work, away from<br />

interruptions <strong>and</strong> distractions.<br />

Sharing workspace with other organisations also provides<br />

opportunities for interaction with people from other professions which<br />

may lead to the development of new business ideas or projects as<br />

well as opportunities for career development <strong>and</strong> networking.<br />

THE SPACE ENVIRONMENT MODEL<br />

The SANE space environment model looks beyond the idea that<br />

technology is a mere supplement to physical space. The model can<br />

be used at various stages of the briefing process: to help<br />

organisations, which provide space in order to support their goals, to<br />

develop strategies for the nature <strong>and</strong> use of that space; it will assist<br />

those who develop space, in their goal of producing relevant design<br />

solutions; <strong>and</strong> it will provide the knowledge workers who use the<br />

space with a means of defining <strong>and</strong> describing the best range of<br />

options <strong>and</strong> protocols for them <strong>and</strong> their working practices.<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257 15

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

In the face of rapidly developing technology <strong>and</strong> work practices, it is<br />

also necessary to move beyond the idea that the best approach to<br />

gaining a comprehensive underst<strong>and</strong>ing of, or the best way of<br />

providing, appropriate environments for knowledge work is via the<br />

identification of a definitive list of work settings <strong>and</strong> work activities,<br />

<strong>and</strong> a direct matching of items from the former list with those from the<br />

latter.<br />

A more useful approach is the identification of <strong>and</strong> careful<br />

consideration of the core contextual variables which may<br />

characterise, or impact on, any given activity within an organisational<br />

context; these mediating variables should inform decisions about the<br />

types of work environments <strong>and</strong> supporting technology which will<br />

best support those activities.<br />

Equally, when thinking about work settings, whether physical or<br />

virtual, it is necessary to consider the places <strong>and</strong> environments which<br />

set the context. The term ‘workscape’ is used to describe the<br />

complete ‘place-with-technology’ environment. Workscapes vary<br />

along certain characteristics <strong>and</strong> it is through the matching of the<br />

mediating factors of activities in their wider business milieu with the<br />

characteristics of the range of available workscapes that an<br />

organisation can ensure that it is providing the right mix of<br />

environments.<br />

When deciding on the most appropriate workscape – including both<br />

real <strong>and</strong> virtual ‘places’ – in which to carry out a work activity, four<br />

different kinds of factors must be taken into account.<br />

First, there is the nature of the activity itself – for example, does it<br />

require a place where one can concentrate, does it require the<br />

participation of other people, is this particular <strong>doc</strong>ument or<br />

conversation confidential Obviously, these may in part derive from<br />

the nature of the task or business process to which this activity<br />

contributes.<br />

Second, there is the wider context of the other activities that the<br />

person is carrying out during the same time period, which will<br />

influence the location chosen for the activity.<br />

Third, there are the preferences (both enduring <strong>and</strong> temporary) <strong>and</strong><br />

goals of the individual (for example, do they prefer a particular type of<br />

workscape, do they need to be near the child minder’s house today,<br />

do they generally want to minimise commuting).<br />

Fourth, there is the background context of the organisational goals,<br />

values <strong>and</strong> culture; for example, does the organisation place a high<br />

value on team-working or, conversely, is the culture one of collegiate<br />

working of autonomous individuals<br />

These four kinds of factors collectively are here termed ‘mediating<br />

factors of the activity’. The identification of the key mediating factors<br />

for a particular activity will enable informed decisions to be made as<br />

to the most appropriate workscape for an activity, these decisions<br />

taking into account wider organisational factors such as the goals<br />

<strong>and</strong> values of the organisation, the relative importance to the<br />

organisation of the task of which this activity forms a part, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

dem<strong>and</strong>s of other tasks.<br />

16 SANE IST-2000-25257

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

The physical l<strong>and</strong>scape of work can be described in three parts –<br />

work settings, work arenas, work environments, each is defined in<br />

scale <strong>and</strong> context in relation to the others. A work setting (such as<br />

‘an L-shaped desk <strong>and</strong> chair’ or ‘a sofa’) cannot be judged without<br />

taking into account its surrounding context - the particular work arena<br />

(the collection of work settings which make up a coherent ‘place’ both<br />

physically <strong>and</strong> psychologically) in which the setting is located.<br />

However, the distributed workplace model describes work taking<br />

place beyond, <strong>and</strong> no longer constrained by, the context of the<br />

traditional office. Therefore, not only the work arena but also, the<br />

context of the wider work environment must also be taken into<br />

account.<br />

Developments in information technology have enabled activities that<br />

would normally take place in a single physical place to be conducted<br />

when one or more of the participants are in different locations. Thus,<br />

virtual or hybrid work settings must also be included in an<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the workscape.<br />

The immediate environment that the body interacts with can be<br />

described as a work setting. It is the smallest unit of analysis of an<br />

overall working environment to which some ‘use-meaning’ still<br />

applies. It should be noted, however, that work settings comprise a<br />

number of components, such as a desk, a chair, a full height<br />

partition, a medium-height screen, <strong>and</strong> so on. These are termed<br />

‘work setting elements’.<br />

Virtual work settings are described as any non-physical ‘space’<br />

which can be used to facilitate work. A factor shared by most virtual<br />

environments is that they are in some way designed to facilitate<br />

communication <strong>and</strong>/or collaborative work. (The desktop of a<br />

computer not connected to a network is one of the few examples of a<br />

virtual work setting oriented wholly towards individual work.)<br />

Collaborative Virtual Environments (CVE) can be as basic as e-mail,<br />

a text-based asynchronous form of communication, <strong>and</strong> as complex<br />

as a Virtual Reality space with ‘walking, talking’ 3-D representations<br />

of the participants.<br />

A work arena is a collection of one or more work settings that forms<br />

somewhere with the psychological status of a ‘place’ – that is, it has<br />

some meaning associated with it which would be largely shared by<br />

everyone within the culture or society using that arena.<br />

Work environments are the highest level of the physical<br />

environment which needs to be taken into account in this analysis.<br />

Examples include an office building, an airport departure terminal, a<br />

train, a city street. It should be noted that the same kind of work<br />

arena can exist in more than one type of work environment, <strong>and</strong> this<br />

will alter its nature. For example, a business lounge might be within a<br />

private office building, or might be a privileged space in an airport. A<br />

cafe might be a public space within a city street, or might be a within<br />

a private office building. Conversely, work environments will often<br />

contain a variety of work arenas - an airport, for example, contains<br />

café areas as well as business lounges.<br />

The combination of virtual <strong>and</strong> real work settings within a work arena,<br />

located in a work environment is described as ‘the workscape’. The<br />

decision to use a physical or virtual setting to support an activity will<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257 17

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

depend on the mediating variables of the activity. For example,<br />

physical places can often reduce the effectiveness of an activity, for<br />

example, due to their remoteness (causing lengthy <strong>and</strong> difficult<br />

journeys that leave limited time <strong>and</strong> energy for working) or their lack<br />

of privacy. However, the absence of the physical presence of the<br />

other person when working in a virtual setting might diminish the<br />

success of that activity, depending upon the activity’s mediating<br />

factors. Being able to establish the right kind of work environment for<br />

the activity is paramount.<br />

WORK SETTING ELEMENT<br />

Desk<br />

Table<br />

Chair<br />

Filing cabinet<br />

Plant<br />

Power<br />

Wall<br />

Partition<br />

Task light<br />

Down light<br />

Telephone<br />

Computer<br />

Network connection<br />

Whiteboard<br />

Data projector<br />

Printer<br />

Photocopier<br />

WORK SETTING<br />

physical<br />

L-SHAPED DESK & CHAIR<br />

SMALL TABLE/FOR 3-4<br />

LARGE TABLE/FOR 6-8<br />

SOFA<br />

QUIET BOOTH<br />

BROWSERY<br />

SEAT<br />

virtual<br />

VIDEO CONFERENCE<br />

INSTANT MESSAGING<br />

SHARED VISUALISATION<br />

CHAT ROOM<br />

e-WHITEBOARD<br />

e-MAIL<br />

VR WORLD/ AVATAR<br />

TEXT MESSAGE<br />

VOICEMAIL<br />

WORK ARENA<br />

TEAM/PROJECT AREA<br />

BUSINESS LOUNGE<br />

CLUB<br />

CAFÉ<br />

PICNIC AREA<br />

MEETING ROOM<br />

MEETING AREA<br />

INDIVIDUAL OFFICE<br />

WORK ENVIRONMENT<br />

ORGANISATION OFFICE<br />

SERVICED OFFICE<br />

BUSINESS CENTRE<br />

AIRPORT<br />

RAILWAY STATION<br />

STREET/CITY<br />

PARK<br />

TRANSPORTATION<br />

(TRAIN, PLANE, CAR)<br />

HOME<br />

In the same way that the particular mediating factors of activities can<br />

be identified, workscapes can be seen to vary across certain<br />

dimensions or characteristics that can then be used to define their<br />

suitability for particular activities. These dimensions or include the<br />

following:<br />

• Accessibility to people –the knowledge community<br />

• Accessibility to information/data<br />

• Ability to control boundaries (control access of others to oneself)<br />

• Ability to support group or collaborative work<br />

• Ability to control confidentiality<br />

• Degree of ‘presence’ available<br />

The approach suggested in this <strong>doc</strong>ument is to match sets of<br />

mediating factors relating to the activity in question with sets of<br />

characteristics of the possible workscapes, to find the most<br />

appropriate match. This process is illustrated in figure 4 below– in<br />

essence, the SANE space environment model in its final form.<br />

WORKSCAPE<br />

FIGURE 3. STRUCTURE OF THE WORKSCAPE AND SOME EXAMPLES OF<br />

COMPONENTS<br />

18 SANE IST-2000-25257

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

organisational<br />

context<br />

business process<br />

<strong>and</strong> task<br />

activity<br />

mediating<br />

factors<br />

WORK SETTING ELEMENT WORK SETTING<br />

WORK ARENA<br />

physical<br />

Desk<br />

Table<br />

L-SHAPED DESK & CHAIR<br />

TEAM/PROJECT AREA<br />

Chair<br />

SMALL TABLE/FOR 3-4<br />

LARGE TABLE/FOR 6-8<br />

Filing cabinet<br />

BUSINESS LOUNGE<br />

SOFA<br />

Plant<br />

QUIET BOOTH<br />

Power<br />

CLUB<br />

BROWSERY<br />

Wall<br />

SEAT<br />

Partition<br />

CAFÉ<br />

Task light<br />

Down light<br />

Telephone<br />

Computer<br />

Network connection<br />

Whiteboard<br />

Data projector<br />

Printer<br />

Photocopier<br />

virtual<br />

VIDEO CONFERENCE<br />

INSTANT MESSAGING<br />

SHARED VISUALISATION<br />

CHAT ROOM<br />

e-WHITEBOARD<br />

e-MAIL<br />

VR WORLD/ AVATAR<br />

TEXT MESSAGE<br />

VOICEMAIL<br />

PICNIC AREA<br />

MEETING ROOM<br />

MEETING AREA<br />

INDIVIDUAL OFFICE<br />

WORKSCAPE<br />

characteristics<br />

of workscapes<br />

WORK ENVIRONMENT<br />

ORGANISATION OFFICE<br />

SERVICED OFFICE<br />

BUSINESS CENTRE<br />

AIRPORT<br />

RAILWAY STATION<br />

STREET/CITY<br />

PARK<br />

TRANSPORTATION<br />

(TRAIN, PLANE, CAR)<br />

HOME<br />

offices) should house, in terms of the range of physical work settings,<br />

the work arenas these settings are formed into, <strong>and</strong> the work<br />

environments in which these work arenas are situated, based on the<br />

business processes that will be carried out there. They could also<br />

identify at a generic level the technical infrastructure <strong>and</strong> hardware<br />

which is needed to provide the virtual settings which would be<br />

available within these physical locations. In parallel with this, they<br />

could develop a strategy for how <strong>and</strong> where their staff should work<br />

(including, but not limited to, a homeworking policy), <strong>and</strong> identify the<br />

preferred geographical distribution of the workscapes their staff will<br />

use.<br />

©DEGW 2002<br />

FIGURE 4. MOVING FROM ACTIVITIES TO WORKSCAPES<br />

In <strong>summary</strong>, the choice of workscape should be based on a<br />

consideration not just of the immediate activity a knowledge worker is<br />

carrying out, plus the individual knowledge worker’s personal<br />

preferences, but also on the wider organisational context, the<br />

objectives of the team, the values <strong>and</strong> goals of the organisation <strong>and</strong><br />

the well-being of the wider society.<br />

The ideas discussed here can be applied in two different sets of<br />

circumstances. First, they can be used to aid organisational-level<br />

decisions about property strategy. Property professionals within an<br />

organisation could use the approach described here to determine<br />

what their office buildings (whether owned, leased or serviced<br />

It is envisaged that this would be carried out in a workshop context,<br />

with a team from the organisation using the contextual factors <strong>and</strong><br />

workscape characteristics as a tool for analysing the way their own<br />

organisation functions <strong>and</strong> could function. Such a process could<br />

bring to light particular factors or characteristics of importance which<br />

may not be listed here; in particular, it will clarify exactly which<br />

business context factors are of importance to the organisation in<br />

question.<br />

In a similar way, providers of office space could use the ideas to help<br />

develop briefs for the accommodation they will provide in the future.<br />

The second level at which these ideas can be applied is at the point<br />

of individual <strong>and</strong> team decision-making about where <strong>and</strong> how to work<br />

on a specific activity <strong>and</strong> task or set of current activities <strong>and</strong> tasks. It<br />

is envisaged that initially, teams would use a workshop to develop<br />

guidelines for what workscapes they would use for which activities,<br />

SANE IST 2000-25257 19

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

taking into account relevant contextual factors. Subsequent to that,<br />

individuals <strong>and</strong> groups should have little trouble in identifying which<br />

workscapes to use for their various activities; indeed, the<br />

predictability of this is seen as very important in allowing teams to<br />

carry out their work smoothly <strong>and</strong> in a co-ordinated fashion whilst still<br />

allowing them individual autonomy – distributed working must not<br />

appear to any of the staff whom it affects as either unpredictable or<br />

uncontrolled. The question of autonomy <strong>and</strong> control is crucial within<br />

knowledge work, for the individual, the organisation <strong>and</strong> the wider<br />

society.<br />

A SANE STRATEGY<br />

Using the concepts described previously it is possible to construct a<br />

methodology for creating <strong>and</strong> implementing a distributed workplace<br />

strategy (summarised in figure 5). This will require the active<br />

participation of a multi-disciplinary team drawn from within the<br />

organisation <strong>and</strong> external consultants. The exact composition of the<br />

team will depend on factors such as the skills within each<br />

organisation, timescales <strong>and</strong> resource availability. It should be noted<br />

that the consultancy process described in this <strong>doc</strong>ument relates to<br />

the development of a workplace strategy <strong>and</strong> the implementation of<br />

this strategy may simply result in better use of existing resources or<br />

the <strong>introduction</strong> of new ICT tools, changes in work process or the<br />

intgration of sustainability issues into general process rather than the<br />

construction of new buildings or facilities which is the traditional ‘end<br />

result’ of workplace projects.<br />

At each stage it is necessary to consider sustainability, ICT <strong>and</strong><br />

human communications issues as well as the issues that are more<br />

typically part of a workplace implementation project.<br />

The implementation of a distributed working strategy will require<br />

careful planning involving all areas of the business. Critical issues to<br />

be considered include:<br />

• Costs <strong>and</strong> benefits of implementing the strategy (real estate<br />

savings, investment costs in IT <strong>and</strong> provision of business<br />

services)<br />

• Risks to business delivery<br />

• HR policies on remote working<br />

• Provision of training<br />

• Corporate br<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

• Maintenance of community <strong>and</strong> culture<br />

• Knowledge management<br />

• Management of teams <strong>and</strong> individuals<br />

• Confidentiality<br />

• Client perceptions<br />

• Provision of business services<br />

20 SANE IST-2000-25257

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

Defining the business<br />

context<br />

Focus on:<br />

Business<br />

context<br />

Business<br />

process<br />

Work styles<br />

Developing the strategy<br />

Workscapes<br />

Workplace<br />

strategy<br />

Implementing the strategy<br />

Implementation<br />

& operation<br />

Workplace evaluation<br />

& improvement<br />

Goals<br />

• Underst<strong>and</strong>ing the<br />

business<br />

• Defining project<br />

goals <strong>and</strong> vision<br />

• Identifying project<br />

KPIs<br />

Define the current<br />

<strong>and</strong> desired future<br />

business processes<br />

Underst<strong>and</strong> how<br />

people work now<br />

<strong>and</strong> aspirations for<br />

the future<br />

Determine the range of<br />

workscapes needed to<br />

support the work<br />

process: organizational<br />

<strong>and</strong> individual<br />

requirements<br />

Define appropriate<br />

distributed<br />

workplace solution<br />

• owned space<br />

• shared space<br />

• home working<br />

• mobile working<br />

• Develop the<br />

workplace design<br />

• Selecting the actual<br />

shared componets<br />

• Implementing the<br />

workplace strategy<br />

• Evaluate<br />

performance on KPIs<br />

• Inform strategy of<br />

next project or refine<br />

current project<br />

Examples of appropriate tools <strong>and</strong> methods<br />

• Interviews with Senior<br />

Managers<br />

• New Economy<br />

Envisioning<br />

• Review of business<br />

plan<br />

• Sustainability audit<br />