Investing in the future: Creating opportunities for young rural ... - IFAD

Investing in the future: Creating opportunities for young rural ... - IFAD

Investing in the future: Creating opportunities for young rural ... - IFAD

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

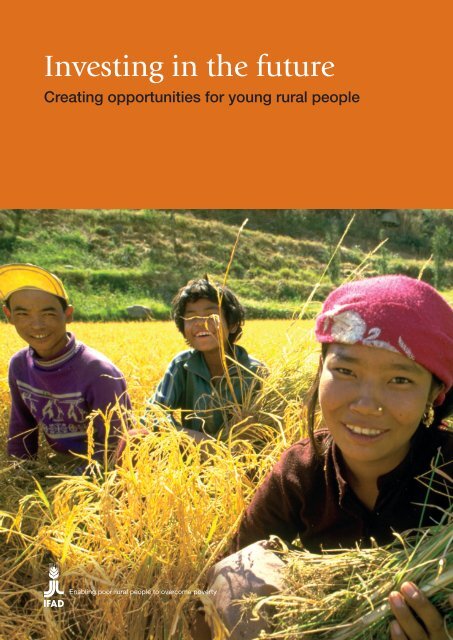

<strong>Invest<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>future</strong><br />

Creat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>young</strong> <strong>rural</strong> people

<strong>Invest<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>future</strong><br />

Creat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>young</strong> <strong>rural</strong> people<br />

Paul Bennell<br />

December 2010<br />

The op<strong>in</strong>ions expressed <strong>in</strong> this paper are those of <strong>the</strong> author and do not necessarily<br />

represent those of <strong>the</strong> International Fund <strong>for</strong> Agricultural Development (<strong>IFAD</strong>). The<br />

designations employed and <strong>the</strong> presentation of material <strong>in</strong> this publication do not imply<br />

<strong>the</strong> expression of any op<strong>in</strong>ion whatsoever on <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>IFAD</strong> concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> legal status<br />

of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> delimitation<br />

of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations “developed” and “develop<strong>in</strong>g” countries<br />

are <strong>in</strong>tended <strong>for</strong> statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement<br />

about <strong>the</strong> stage reached by a particular country or area <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> development process.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS<br />

CIS<br />

EGMM<br />

EU<br />

FAO<br />

IFPRI<br />

ILO<br />

MDGs<br />

NENA<br />

NGO<br />

PRSP<br />

RNF<br />

SSA<br />

UWESO<br />

WDR<br />

YEN<br />

Commonwealth of Independent States<br />

Employment Generation and Market<strong>in</strong>g Mission<br />

European Union<br />

Food and Agriculture Organization of <strong>the</strong> United Nations<br />

International Food Policy Research Institute<br />

International Labour Office<br />

The United Nations‟ Millennium Development Goals<br />

Near East and North Africa<br />

Non-governmental organization<br />

Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper<br />

Rural non-farm<br />

Sub-Saharan Africa<br />

Uganda Women‟s Ef<strong>for</strong>t to Save Orphans<br />

World Development Report<br />

Youth Employment Network

INTRODUCTION<br />

This paper 1 reviews <strong>the</strong> situation of <strong>rural</strong> youth <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries and<br />

presents options <strong>for</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir livelihoods <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> face of <strong>the</strong> many grow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

challenges <strong>the</strong>y face. The ma<strong>in</strong> geographical focus is sub-Saharan Africa and <strong>the</strong><br />

Near East and North Africa.<br />

Rural youth <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries make up a very large and vulnerable group<br />

that is seriously affected by <strong>the</strong> current <strong>in</strong>ternational economic crisis. Globally,<br />

three-quarters of <strong>the</strong> poor live <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas, and about one-half of <strong>the</strong><br />

population are <strong>young</strong> people. Climate change and <strong>the</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g food crisis are also<br />

expected to have a disproportionately high impact on <strong>rural</strong> youth. The Food and<br />

Agriculture Organization of <strong>the</strong> United Nations (FAO) estimates that nearly half a<br />

billion <strong>rural</strong> youth „do not get <strong>the</strong> chance to realize <strong>the</strong>ir full potential‟ (FAO,<br />

2009). The 2005 International Labour Organization (ILO) report on Global<br />

Employment Trends <strong>for</strong> Youth states: “today‟s youth represent a group with<br />

serious vulnerabilities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world of work. In recent years, slow<strong>in</strong>g global<br />

employment growth and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g unemployment, underemployment and<br />

disillusionment have hit <strong>young</strong> people hardest. As a result, today‟s youth are<br />

faced with a grow<strong>in</strong>g deficit of decent work <strong>opportunities</strong> and high levels of<br />

economic and social uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty” (ILO, 2005: p.1). The lack of decent<br />

employment ra<strong>the</strong>r than open unemployment is <strong>the</strong> central issue <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> majority<br />

of <strong>rural</strong> locations. In overall terms, four times as many <strong>young</strong> people earn less<br />

than US$ 2 a day than who are unemployed. Youth are particularly vulnerable <strong>in</strong><br />

conflict and post-conflict countries. Very high youth unemployment coupled with<br />

rapid urbanization has fuelled civil conflict <strong>in</strong> many countries.<br />

It is widely recognized that smallholder agriculture and non-farm production <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>rural</strong> areas are among <strong>the</strong> most promis<strong>in</strong>g sectors <strong>for</strong> youth employment <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

majority of develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. However, harness<strong>in</strong>g this potential rema<strong>in</strong>s an<br />

enormous challenge.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> crisis of „youth unemployment‟ (particularly <strong>in</strong> urban areas) has been a<br />

persistent concern of politicians and policymakers s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> 1960s, youth<br />

development has rema<strong>in</strong>ed at <strong>the</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>s of national development strategies <strong>in</strong><br />

most countries. We are now witness<strong>in</strong>g, however, a resurgence of <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong><br />

youth, <strong>the</strong> reasons <strong>for</strong> which stem from a grow<strong>in</strong>g realisation of <strong>the</strong> seriously<br />

negative political, social and economic consequences stemm<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong><br />

precariousness of youth livelihoods. For many, this amounts to a „youth crisis‟,<br />

<strong>the</strong> resolution of which requires <strong>in</strong>novative, wide-rang<strong>in</strong>g „youth-friendly‟ policies<br />

and implementation strategies.<br />

The United Nations‟ Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) s<strong>in</strong>gle out youth as a<br />

key target group. Target 16 of <strong>the</strong> MDGs is to develop and implement strategies<br />

<strong>for</strong> decent and productive work <strong>for</strong> youth. The 2007 World Development Report<br />

published by <strong>the</strong> World Bank also focused on youth.<br />

1 The orig<strong>in</strong>al version of this paper was presented at <strong>the</strong> 2007 <strong>IFAD</strong> Govern<strong>in</strong>g Board<br />

Meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Rome. It has been revised to take <strong>in</strong>to account <strong>the</strong> latest developments <strong>in</strong> this<br />

area, especially <strong>IFAD</strong> support <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> livelihood programm<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

1

The global population of <strong>young</strong> people aged 12-24 is about 1.3 billion. The youth<br />

population is projected to peak at 1.5 billion <strong>in</strong> 2035 and it will <strong>in</strong>crease most<br />

rapidly <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia (by 26 per cent and<br />

20 per cent respectively between 2005 and 2035). FAO estimates that about<br />

55 per cent of youth reside <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas, but this figure is as high as 70 per<br />

cent <strong>in</strong> SSA and South Asia. In SSA, <strong>young</strong> people aged 15-24 comprise 36 per<br />

cent of <strong>the</strong> entire labour <strong>for</strong>ce, 33 per cent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Near East and North Africa<br />

(NENA), and 29 per cent <strong>in</strong> South Asia. About 85 per cent of <strong>the</strong> additional<br />

500 million <strong>young</strong> people who will reach work<strong>in</strong>g age dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> next decade live<br />

<strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. The global economic downturn has accelerated <strong>the</strong><br />

growth of <strong>the</strong> <strong>rural</strong> youth population because many <strong>young</strong> migrants to urban<br />

areas are return<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>rural</strong> homes and o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>young</strong> people are discouraged<br />

from migrat<strong>in</strong>g to urban areas.<br />

Globally, youth are nearly three times more likely to be unemployed than adults<br />

(ILO, 2010) 2 . However, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>cidence of youth unemployment varies considerably<br />

from one region to ano<strong>the</strong>r. It is highest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NENA region, where nearly onequarter<br />

of all youth are classified as be<strong>in</strong>g unemployed. It is lowest <strong>in</strong> East Asia<br />

and South Asia with rates of 9.0 per cent and 10.7 per cent respectively. Youth<br />

unemployment <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa was 12.6 per cent <strong>in</strong> 2009 (table 1).<br />

(Breakdowns of <strong>rural</strong> and urban youth unemployment rates are not available.)<br />

Particularly high rates of youth unemployment are closely l<strong>in</strong>ked with high rates<br />

of landlessness – <strong>for</strong> example, 20 per cent <strong>in</strong> NENA.<br />

Table 1: Youth unemployment rates by region<br />

1999 and 2009<br />

Region 1999 2009<br />

Developed economies and EU 13.9 17.7<br />

Central and Eastern Europe and CIS 22.7 21.5<br />

East Asia 9.2 9.0<br />

South East Asia and Pacific 13.1 15.3<br />

South Asia 9.8 10.7<br />

Lat<strong>in</strong> America and <strong>the</strong> Caribbean 15.6 16.6<br />

Middle East<br />

North Africa<br />

20.5<br />

27.3<br />

22.3<br />

24.7<br />

Sub-Saharan Africa 12.6 12.6<br />

Source: ILO, Global Employment Trends, 2010.<br />

A. WHO ARE RURAL YOUTH<br />

Age and location are <strong>the</strong> two key def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g characteristics of <strong>rural</strong> youth. Age<br />

def<strong>in</strong>itions of youth vary quite considerably. The United Nations def<strong>in</strong>es youth as<br />

all <strong>in</strong>dividuals aged between 15 and 24. The 2007 World Development Report,<br />

which focuses on „<strong>the</strong> next generation‟, expands <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition of youth to <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

all <strong>young</strong> people aged between 12 and 14. Similar def<strong>in</strong>itional variations exist<br />

with regard to location. Dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g between who is <strong>rural</strong> and who is urban is<br />

2 Young people aged 15-24 are estimated to account <strong>for</strong> 60 per cent of <strong>the</strong> unemployed <strong>in</strong> sub-<br />

Saharan Africa.<br />

2

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly difficult, especially with <strong>the</strong> expansion of „peri-urban‟ areas where<br />

large proportions of <strong>the</strong> population rely on agricultural activities to meet <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

livelihood needs.<br />

Traditionally, policy discussions concern<strong>in</strong>g youth have been based on <strong>the</strong><br />

premise that youth are <strong>in</strong> transition from childhood to adulthood and, as such,<br />

have specific characteristics that make <strong>the</strong>m a dist<strong>in</strong>ct demographic and social<br />

category. This transition is multi-faceted. It <strong>in</strong>volves <strong>the</strong> sexual maturation of<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals and <strong>the</strong>ir grow<strong>in</strong>g autonomy social and economic <strong>in</strong>dependence from<br />

parents and o<strong>the</strong>r carers.<br />

The nature of <strong>the</strong> transition from childhood to adulthood has changed over time<br />

and varies considerably from one region to ano<strong>the</strong>r. Rural children <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

countries become adults quickly ma<strong>in</strong>ly because <strong>the</strong> transition from school to<br />

work usually occurs at an early age and is completed <strong>in</strong> a short space of time.<br />

The same is true <strong>for</strong> poor <strong>young</strong> <strong>rural</strong> women with regard to marriage and<br />

childbear<strong>in</strong>g. „Lack of alternatives‟ is <strong>the</strong> major reason given <strong>for</strong> very high levels<br />

of marriage and childbear<strong>in</strong>g among <strong>rural</strong> adolescent girls. Rural survival<br />

strategies demand that <strong>young</strong> people fully contribute to meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> livelihood<br />

needs of <strong>the</strong>ir households from an early age. Consequently, youth as a<br />

transitional stage barely exists <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> large majority of <strong>rural</strong> youth, and <strong>the</strong> poor<br />

<strong>in</strong> particular. Many children aged 5-14 also work (<strong>for</strong> example, 80 per cent <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>rural</strong> Ethiopia).<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r related attribute of <strong>rural</strong> youth is that <strong>the</strong>y tend to lack economic<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependence or „autonomy‟. The <strong>rural</strong> household is a jo<strong>in</strong>t venture, and <strong>the</strong><br />

gender division of labour is such that full, <strong>in</strong>dividual control of <strong>the</strong> productive<br />

process is virtually impossible <strong>for</strong> women <strong>in</strong> many countries. Given that large<br />

proportions of <strong>rural</strong> youth are subord<strong>in</strong>ate members of usually large extended<br />

households, <strong>the</strong>y are largely dependent on <strong>the</strong>ir parents <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir livelihood<br />

needs. As youth grow older, <strong>the</strong> autonomy of males <strong>in</strong>creases, but contracts <strong>for</strong><br />

females. Moreover, <strong>in</strong> most traditional and poorest populations <strong>in</strong> low-<strong>in</strong>come<br />

countries, girls typically marry shortly after menarche or when <strong>the</strong>y leave school.<br />

Rural youth are also very heterogeneous. The World Bank def<strong>in</strong>ition of youth<br />

encompasses <strong>the</strong> 12 year-old pre-pubescent boy attend<strong>in</strong>g primary school <strong>in</strong> a<br />

remote <strong>rural</strong> area and a 24-year old s<strong>in</strong>gle mo<strong>the</strong>r of four children ek<strong>in</strong>g out an<br />

existence vend<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> streets of a large <strong>rural</strong> village. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>ir livelihood<br />

needs are markedly different, <strong>the</strong>y require very different sets or „packages‟ of<br />

policy <strong>in</strong>terventions. The same is true <strong>for</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r dist<strong>in</strong>ct groups of <strong>rural</strong><br />

disadvantaged youth <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> disabled, ex-combatants, and orphans. A clear<br />

separation also has to be made between school-aged youth and post-school<br />

youth. One of <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> reasons why youth programm<strong>in</strong>g has attracted so little<br />

support from governments, NGOs and donor agencies is that post-school youth<br />

are usually subsumed <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> adult population as a whole. The implicit<br />

assumption is, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, that this group does not face any additional problems<br />

access<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> limited support services that are available <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> adult population<br />

as a whole. Nor do <strong>the</strong>y have any social and economic needs that relate<br />

specifically to <strong>the</strong>ir age that would give <strong>the</strong>m priority over an above o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

economically excluded and socially vulnerable groups. The logical conclusion of<br />

this l<strong>in</strong>e of argument is that, given <strong>the</strong> limited relevance of youth as a dist<strong>in</strong>ct<br />

and protracted transitional phase <strong>in</strong> most <strong>rural</strong> areas coupled with <strong>the</strong><br />

3

heterogeneity of <strong>rural</strong> youth, youth may have limited usefulness as a social<br />

category around which major <strong>rural</strong> development policy <strong>in</strong>itiatives should be<br />

developed.<br />

It is certa<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>the</strong> case that, with a few exceptions (such as South Africa), youth<br />

as a target group is not a major policy priority of most governments <strong>in</strong> low<strong>in</strong>come<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. M<strong>in</strong>istries of Youth are generally very poorly<br />

resourced and are usually subsumed (or comb<strong>in</strong>ed) with o<strong>the</strong>r government<br />

responsibilities, most commonly culture, sports and education. With regard to<br />

national poverty alleviation strategies, youth receives very little attention <strong>in</strong> most<br />

Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs). A 2005 overview of PRSPs<br />

conducted by <strong>the</strong> Economic Commission <strong>for</strong> Africa concluded that „youth are still<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g overlooked‟. In particular, <strong>the</strong> chapters <strong>in</strong> PRSPs on agriculture rarely<br />

mention youth. Similarly, <strong>the</strong> standard chapter on „crosscutt<strong>in</strong>g‟ issues focuses<br />

only on gender, environment and HIV/AIDS. In only two out of 12 PRSPs <strong>for</strong><br />

African countries that were reviewed youth is s<strong>in</strong>gled out as a „special group <strong>in</strong><br />

ma<strong>in</strong>stream<strong>in</strong>g employment‟, and, even <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se exceptional cases, urban youth<br />

is of greater concern than <strong>rural</strong> youth. Even <strong>the</strong> current World Development<br />

report on youth, devotes only four paragraphs to how to expand <strong>rural</strong><br />

<strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> youth and focuses ma<strong>in</strong>ly on <strong>rural</strong> non-farm activities.<br />

Only a relatively small number of recent <strong>IFAD</strong> projects specifically targeted<br />

youth. These projects were ma<strong>in</strong>ly concentrated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NENA region, where levels<br />

of open unemployment among <strong>rural</strong> youth are particularly high. However,<br />

considerably more attention is now be<strong>in</strong>g given to youth programm<strong>in</strong>g, with a<br />

particular focus on promot<strong>in</strong>g youth employment through both farm and nonfarm<br />

enterprise development. In <strong>the</strong> past, <strong>IFAD</strong> provided only limited fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong><br />

capacity development, especially skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, <strong>for</strong> youth <strong>in</strong> agricultural<br />

activities. In part, this was because <strong>the</strong>re is no specific education component <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>IFAD</strong>‟s core mandate, although vocational tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is offered across all<br />

agricultural specializations. <strong>IFAD</strong> is, however, becom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong><br />

provid<strong>in</strong>g support <strong>for</strong> targeted tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> <strong>young</strong> farmers.<br />

B. KEY FEATURES OF RURAL YOUTH LIVELIHOODS<br />

Most <strong>rural</strong> youth are ei<strong>the</strong>r employed (waged and self-employed) or not <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

labour <strong>for</strong>ce. The issue, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, is not so much about unemployment, but<br />

serious under-employment <strong>in</strong> low productivity, predom<strong>in</strong>antly household-based<br />

activities. The ILO estimates that about 300 million youth (one-quarter of <strong>the</strong><br />

total) live on less than US$ 2 a day. The unemployed are ma<strong>in</strong>ly better-educated<br />

urban youth who can af<strong>for</strong>d to engage <strong>in</strong> relatively protracted job searches. It is<br />

better, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, to focus on improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> livelihoods of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

disadvantaged youth ra<strong>the</strong>r than those who are unemployed. Access to key<br />

productive assets, particularly land, is a critical issue <strong>for</strong> <strong>young</strong> people.<br />

It is often argued (although usually not based on robust evidence) that <strong>rural</strong><br />

youth are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly dis<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> smallholder farm<strong>in</strong>g and tend to travel<br />

nationally and, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly, across <strong>in</strong>ternational borders, <strong>in</strong> search of<br />

employment. This exodus of <strong>young</strong> people from <strong>rural</strong> areas is result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a<br />

marked age<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> <strong>rural</strong> population <strong>in</strong> some countries. In some prov<strong>in</strong>ces <strong>in</strong><br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a, <strong>for</strong> example, <strong>the</strong> average age of farmers is 45-50 years. Recent research<br />

4

shows that migration from <strong>rural</strong> to urban areas will cont<strong>in</strong>ue on a large scale,<br />

and that this is an essential part of <strong>the</strong> livelihood cop<strong>in</strong>g strategies of <strong>the</strong> <strong>rural</strong><br />

poor. Temporary migration and commut<strong>in</strong>g are also a rout<strong>in</strong>e part of <strong>the</strong><br />

comb<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>rural</strong>-urban livelihood strategies of <strong>the</strong> poor across a wide range of<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries (Desh<strong>in</strong>gkar, 2004). In many parts of Asia and Africa,<br />

remittances from <strong>rural</strong> to urban migration are overtak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>come from<br />

agriculture. It is important, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, that <strong>young</strong> people <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas are<br />

prepared <strong>for</strong> productive lives <strong>in</strong> both <strong>rural</strong> and urban environments. Policymakers<br />

should, <strong>in</strong> turn, revise negative perceptions of migration and view migration as<br />

socially and economically desirable (see box).<br />

EGMM <strong>in</strong> Andhra Pradesh<br />

The Employment Generation and Market<strong>in</strong>g Mission (EGMM), which<br />

was established by <strong>the</strong> Andhra Pradesh state government <strong>in</strong> India,<br />

is a good example of a successful, pro-migration employment<br />

generation scheme <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> youth. It relies on an extensive<br />

network of 800,000 self-help groups that works closely with <strong>the</strong><br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess community to help <strong>rural</strong> youth f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>for</strong>mal-sector<br />

employment. Rural academies provide short high-quality, focused<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g courses <strong>in</strong> retail, security, English, work read<strong>in</strong>ess and<br />

computers. Youth tra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> programme earn about three to<br />

four times <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>come of a <strong>rural</strong> farm household <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> state.<br />

Rural youth tend to be poorly educated, especially <strong>in</strong> comparison to urban youth.<br />

The extent of „urban bias‟ <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> provision of publicly funded education and<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g services is large <strong>in</strong> most low-<strong>in</strong>come develop<strong>in</strong>g countries (see Bennell,<br />

1999). The deployment of teachers and o<strong>the</strong>r key workers to <strong>rural</strong> areas<br />

amounts to noth<strong>in</strong>g less than a crisis <strong>in</strong> many countries. Poor quality education,<br />

high (direct and <strong>in</strong>direct) school<strong>in</strong>g costs, and <strong>the</strong> paucity of „good jobs‟ cont<strong>in</strong>ue<br />

to dampen <strong>the</strong> demand <strong>for</strong> education among poor parents.<br />

Rural youth have been heavily <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> civil wars, and o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong>ms of conflict<br />

<strong>in</strong> a grow<strong>in</strong>g number of countries, which poses a major threat to <strong>the</strong> long-term<br />

development prospects of <strong>the</strong>se countries. Traditional safety nets are break<strong>in</strong>g<br />

down and <strong>rural</strong> youth expectations <strong>for</strong> a better life are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g, especially with<br />

access to global <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation technologies.<br />

Rural youth face major health problems, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g malnutrition, malaria, and<br />

HIV/AIDS. It is important, however, to keep <strong>the</strong> direct health threat posed by<br />

HIV/AIDS <strong>in</strong> proper perspective. Except <strong>for</strong> a handful of very high prevalence<br />

countries, HIV prevalence among <strong>rural</strong> teenagers rema<strong>in</strong>s very low. In very large<br />

countries <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa such as Ethiopia, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Congo and all of Asia and Central and South America, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>cidence of HIV<br />

<strong>in</strong>fection among <strong>rural</strong> teenagers is well under one per cent. The ma<strong>in</strong> impact of<br />

<strong>the</strong> AIDS epidemic on <strong>rural</strong> youth livelihoods is <strong>the</strong> rapidly grow<strong>in</strong>g number of<br />

children and youth whose parents have died from AIDS-related illnesses.<br />

5

As with <strong>the</strong> <strong>rural</strong> population as a whole, <strong>rural</strong> youth are engaged <strong>in</strong> a diverse<br />

range of productive activities, both agricultural and non-agricultural. Statistics<br />

are limited, but <strong>the</strong> proportions of <strong>rural</strong> youth engaged <strong>in</strong> waged and selfemployment<br />

<strong>in</strong> both <strong>the</strong>se ma<strong>in</strong> areas of activity varies considerably across<br />

countries.<br />

The lack of access to basic <strong>in</strong>frastructure <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas is also a key issue. In <strong>the</strong><br />

majority of countries <strong>in</strong> SSA, less than 10 per cent of <strong>rural</strong> households have<br />

access to electricity and less than half have access to dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water with<strong>in</strong><br />

15 m<strong>in</strong>utes of <strong>the</strong>ir homes. The impact on youth can be particularly severe. For<br />

example, girls and <strong>young</strong> women are usually responsible <strong>for</strong> water collection, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> lack of electricity seriously limits tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and o<strong>the</strong>r employment creation<br />

<strong>opportunities</strong>.<br />

C. FUTURE LABOUR DEMAND IN RURAL AREAS<br />

Over <strong>the</strong> com<strong>in</strong>g decades, <strong>the</strong>re will be much debate and uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty about <strong>the</strong><br />

roles and contributions of <strong>the</strong> agricultural and <strong>rural</strong> non-farm sectors <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

development process. It is impossible, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, to make robust projections of<br />

<strong>future</strong> labour demand <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas. Rural reality is chang<strong>in</strong>g fast <strong>in</strong> many<br />

countries. Agriculture is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly sophisticated and commercial, and a<br />

grow<strong>in</strong>g share of <strong>rural</strong> <strong>in</strong>comes comes from <strong>the</strong> non-farm economy. Many of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>rural</strong> poor are part-time farmers or are landless.<br />

It is widely recognized that <strong>rural</strong> diversification will be <strong>the</strong> lynchp<strong>in</strong> of successful<br />

agricultural trans<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>future</strong>. Where <strong>rural</strong> diversification is not<br />

economically feasible, <strong>the</strong> alternative will be <strong>the</strong> transition of economic activity<br />

from <strong>rural</strong> to urban areas. Whatever <strong>the</strong> outcome, <strong>rural</strong> youth will be at <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong>efront of this process of change.<br />

Rural non-farm (RNF) activities account <strong>for</strong> a large and grow<strong>in</strong>g share of<br />

employment and <strong>in</strong>come, especially among <strong>the</strong> poor and women who lack key<br />

assets, most notably land. The RNF sector is seen as <strong>the</strong> „ladder‟ from<br />

under-employment <strong>in</strong> low-productivity smallholder production to regular wage<br />

employment <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> local economy and from <strong>the</strong>re to jobs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mal sector.<br />

The key policy goals <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> RNF sector are to identify <strong>the</strong> key eng<strong>in</strong>es of growth,<br />

focus on sub sector-specific supply cha<strong>in</strong>s, and build flexible <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

coalitions of public and private agencies (see Haggblade et al 2002).<br />

Traditionally, manpower planners have assumed that <strong>in</strong>creased demand <strong>for</strong><br />

labour <strong>in</strong> a particular sector, such as smallholder agriculture, depends on <strong>the</strong><br />

projected rate of growth of output and <strong>the</strong> elasticity of employment with respect<br />

to output <strong>for</strong> that specific sector. However, <strong>in</strong> countries without unemployment<br />

benefit systems, <strong>the</strong>se assumptions generally do not apply. 3 Consequently, an<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> demand <strong>for</strong> labour is reflected <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> quality ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than <strong>the</strong> quantity of employment: workers move from unpaid to wage jobs, from<br />

worse jobs to better jobs, etc. Subsistence agriculture and <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mal sectors are<br />

„sponges‟ <strong>for</strong> surplus labour. Also, <strong>the</strong> traditional manpower plann<strong>in</strong>g analysis<br />

3 This is because total employment is largely supply determ<strong>in</strong>ed and employment elasticities of<br />

demand tend to vary <strong>in</strong>versely with output growth.<br />

6

sets up a false conflict between <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g productivity and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g<br />

employment. It leads employment planners to talk about <strong>the</strong> threat posed to<br />

jobs of too fast growth <strong>in</strong> productivity, whereas <strong>the</strong> process is entirely <strong>the</strong><br />

opposite. Increas<strong>in</strong>g productivity is at <strong>the</strong> centre stage <strong>for</strong> any strategy to<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong> quality of employment (Godfrey, 2005 and 2006).<br />

Growth <strong>in</strong> productive-sector wage employment is a source of dynamism <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

labour market as a whole. When wage employment <strong>in</strong>creases, <strong>the</strong> self-employed<br />

<strong>in</strong> both <strong>rural</strong> and urban areas, also face less competition <strong>for</strong> assets and<br />

customers and enjoy an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> demand <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir products. The regions<br />

that have been most successful recently <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g demand <strong>for</strong> labour and<br />

reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>cidence of poverty are those where <strong>the</strong> share of productive-sector<br />

wage earners <strong>in</strong> total employment has been ris<strong>in</strong>g. Unless demand <strong>for</strong> labour is<br />

expand<strong>in</strong>g it is very difficult to design and implement programmes to <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrability of disadvantaged youth.<br />

Boost<strong>in</strong>g labour demand will depend on promot<strong>in</strong>g growth sectors <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>rural</strong><br />

economy <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with dynamic comparative advantage (which will be natural<br />

resource-based <strong>in</strong> most countries) supported by an appropriate macroeconomic<br />

policy framework.<br />

D. IMPROVING YOUTH LIVELIHOODS IN RURAL AREAS<br />

A clear dist<strong>in</strong>ction should be made between, on <strong>the</strong> one hand, social and<br />

economic policies that are not specifically targeted at youth, but none<strong>the</strong>less<br />

benefit youth, ei<strong>the</strong>r directly or <strong>in</strong>directly, and, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, policies that<br />

do target youth as a whole or groups of youth i.e. are youth-specific. It is widely<br />

alleged that youth development is at <strong>the</strong> periphery of <strong>the</strong> development agenda <strong>in</strong><br />

most countries. And yet, given that youth comprise such a large proportion of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>rural</strong> labour <strong>for</strong>ce, most development projects and programmes <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas<br />

do promote youth livelihoods to a large extent. Youth is <strong>the</strong> primary client group<br />

<strong>for</strong> education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programmes as well as health and health prevention<br />

activities. Even so, participatory assessments often show that <strong>rural</strong> communities<br />

want more youth-focused activities.<br />

The 2007 World Development Report (WDR) on youth concludes that „youth<br />

policies often fail‟. Youth policies <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries have frequently been<br />

criticized <strong>for</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g biased towards non-poor, males liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> urban areas. Given<br />

<strong>the</strong> paucity of youth support services <strong>in</strong> many countries, <strong>the</strong>y tend to be<br />

captured by non-poor youth. For example, secondary school-leavers <strong>in</strong> SSA have<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly taken over <strong>rural</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g centres orig<strong>in</strong>ally meant <strong>for</strong> primary schoolleavers<br />

and secondary school dropouts. National youth service schemes enrol<br />

only university graduates and occasionally secondary school leavers, most of who<br />

are nei<strong>the</strong>r poor or from <strong>rural</strong> areas. Many schemes have been scrapped dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> last given deepen<strong>in</strong>g fiscal crises coupled with <strong>the</strong> relatively high costs of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se schemes.<br />

The World Bank‟s 2007 global <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>in</strong>terventions to support <strong>young</strong><br />

workers is based on 289 documented projects and o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>in</strong><br />

84 countries. However, only 13 per cent of <strong>the</strong> projects were <strong>in</strong> SSA and NENA<br />

and less than 10 per cent of <strong>in</strong>terventions were targeted exclusively <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong><br />

7

areas. Two o<strong>the</strong>r notable f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are <strong>the</strong> predom<strong>in</strong>ance of skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>terventions and <strong>the</strong> very limited robust evidence available on project outcomes<br />

and impacts (Betcherman et al, 2007).<br />

A common misconception of youth policy has been that boys and girls are a<br />

homogeneous group. Uncritical focus<strong>in</strong>g on youth could, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, divert<br />

attention away from <strong>the</strong> gender agenda s<strong>in</strong>ce female and male youth often have<br />

conflict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terests. Rural adolescent girls are virtually trapped with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

domestic sphere <strong>in</strong> many countries. Because boys spend more time <strong>in</strong> productive<br />

activities that generate <strong>in</strong>come, <strong>the</strong>y are more visible and are more likely,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, to be supported.<br />

Sexual reproductive health issues have <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly dom<strong>in</strong>ated youth policy<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> last decade. Up to <strong>the</strong> 1990s, <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> preoccupation of governments<br />

and donors was to reduce youth fertility rates (through later marriage and<br />

smaller families). S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>n, <strong>the</strong> focus (<strong>in</strong> at least <strong>in</strong> SSA) has shifted to<br />

reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> risks of HIV <strong>in</strong>fection among youth.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> most general level, youth employment policies should focus on<br />

(i) <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> demand <strong>for</strong> labour <strong>in</strong> relation to supply; and (ii) <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

„<strong>in</strong>tegrability‟ of disadvantaged youth so that <strong>the</strong>y can take advantage of labour<br />

market and o<strong>the</strong>r economic <strong>opportunities</strong> when <strong>the</strong>y arise. There are three ma<strong>in</strong><br />

aspects of youth <strong>in</strong>tegration namely, remedy<strong>in</strong>g or counteract<strong>in</strong>g market failure<br />

(labour, credit, location, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g systems), optimis<strong>in</strong>g labour market regulations,<br />

and improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> skills of disadvantaged youth.<br />

There is a fairly standard list of policy <strong>in</strong>terventions to improve <strong>the</strong> livelihoods of<br />

<strong>rural</strong> youth that are enumerated <strong>in</strong> policy discussions as well as <strong>in</strong> policy<br />

documents and <strong>the</strong> academic literature. The United Nation‟s World Programme of<br />

Action <strong>for</strong> Youth, which was orig<strong>in</strong>ally promulgated <strong>in</strong> 1995, identifies <strong>the</strong><br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g „fields of action‟: education, employment, hunger and poverty, health,<br />

environment, drug abuse, juvenile del<strong>in</strong>quency, and leisure. Youth livelihood<br />

improvement programmes typically dist<strong>in</strong>guish between <strong>in</strong>terventions that<br />

improve capabilities and resources (especially education, health, „life skills‟,<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and f<strong>in</strong>ancial services/credit) and those that structure <strong>opportunities</strong><br />

(<strong>in</strong>dividual and group <strong>in</strong>come generation activities, promot<strong>in</strong>g access to markets,<br />

land, <strong>in</strong>frastructure and o<strong>the</strong>r services), <strong>the</strong> protection and promotion of rights,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> development of youth <strong>in</strong>stitutions.<br />

There is also <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g awareness of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ter-relatedness and l<strong>in</strong>kages between<br />

different k<strong>in</strong>ds of <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>for</strong> youth. In particular, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of <strong>the</strong> AIDS<br />

epidemic, it is contended that improved youth livelihoods may reduce <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>cidence of high-risk „transactional‟ sexual relationships, which are ma<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

motivated by material ga<strong>in</strong> (<strong>the</strong> „sex-<strong>for</strong>-food, food-<strong>for</strong>-sex‟ syndrome).<br />

Integrated programm<strong>in</strong>g is, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, desirable, but is complicated, both with to<br />

programme design and implementation.<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>able livelihoods approach, <strong>the</strong> livelihood „capital assets‟<br />

of <strong>rural</strong> youth can be broken down <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g four ma<strong>in</strong> types: political<br />

and social, physical and natural, human, and f<strong>in</strong>ancial. A wide range of livelihood<br />

improvement <strong>in</strong>terventions has been undertaken with respect to <strong>the</strong>se asset<br />

types. <strong>IFAD</strong>‟s core mandate focuses ma<strong>in</strong>ly on streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> productive base<br />

8

of <strong>rural</strong> households and, as such, is most directly related to <strong>in</strong>terventions that<br />

improve physical and natural and f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets as well as job-related human<br />

capital through skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The available evidence strongly suggests that comprehensive multiple services<br />

approaches (such as <strong>the</strong> Jovenes programmes <strong>in</strong> South America) are more<br />

effective than fragmented <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>for</strong> generat<strong>in</strong>g susta<strong>in</strong>able employment<br />

<strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> youth. However, such approaches are relatively expensive,<br />

which cont<strong>in</strong>ues to limit <strong>the</strong>ir applicability <strong>in</strong> most low-<strong>in</strong>come develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

countries.<br />

Social capital and youth empowerment<br />

Youth, especially <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas, do not usually constitute an organized and vocal<br />

constituency with <strong>the</strong> economic and social power to lobby on <strong>the</strong>ir own behalf.<br />

Consequently, empower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>rural</strong> youth to take an active role <strong>in</strong> agriculture and<br />

<strong>rural</strong> development is critical. Successful youth policies also depend on effective<br />

representation by youth. Traditionally, despite <strong>the</strong>ir size, <strong>rural</strong> youth have had<br />

limited social and political power. Older people, and especially older males, tend<br />

to dom<strong>in</strong>ate decision mak<strong>in</strong>g at all levels <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> societies. In SSA, some writers<br />

refer to this as a gerontocracy. The subord<strong>in</strong>ate position of youth has been<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r compounded by <strong>the</strong> traditional welfare approach – youth are viewed as<br />

present<strong>in</strong>g problems that need to be solved through <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervention of older<br />

people. It is now widely accepted, however, that youth can play a major role <strong>in</strong><br />

improv<strong>in</strong>g governance nationally and locally, and <strong>in</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g key economic<br />

and social policies. In particular, <strong>rural</strong> youth should be at <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>efront of ef<strong>for</strong>ts<br />

to broaden <strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> people. Urban bias with respect to macro-,<br />

sector- and meso-level policies and related resource allocations is also likely to<br />

become even more acute as <strong>the</strong> problems <strong>in</strong> urban areas <strong>in</strong>crease and needs to<br />

be countered. Well-designed <strong>in</strong>terventions are required to build up <strong>the</strong> political<br />

and social capital of <strong>rural</strong> youth. Youth have to be mobilized so that <strong>the</strong>y are able<br />

to participate fully and ga<strong>in</strong> ownership over youth development strategies and<br />

policies. This becomes even more challeng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> <strong>young</strong> people who are under 18<br />

and who are, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, still considered to be children.<br />

New ways of work<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>young</strong> people <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas are be<strong>in</strong>g pioneered <strong>in</strong><br />

many countries. Rural youth organizations and networks should be established<br />

and streng<strong>the</strong>ned. There are many excit<strong>in</strong>g developments <strong>in</strong> this area. For<br />

example, <strong>the</strong> <strong>IFAD</strong>-funded Rural Youth Talents Programme <strong>in</strong> South America is<br />

based on a new strategy that seeks systematize and publicize <strong>the</strong> experiences<br />

and lessons learned from <strong>rural</strong> youth programm<strong>in</strong>g. The ILO-supported Youth-to-<br />

Youth Fund <strong>in</strong> Cote d‟Ivoire, Gu<strong>in</strong>ea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and three East African<br />

countries (Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya) also demonstrates how youth-led<br />

organizations can effectively promote <strong>rural</strong>-based farm<strong>in</strong>g and non-farm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

enterprises. The Mercy Corps Youth Trans<strong>for</strong>mation Framework has adopted a<br />

similar approach <strong>in</strong> 40 fragile environment countries. Community Action Plans<br />

have been successfully piloted <strong>in</strong> Jordan, which map youth livelihood<br />

<strong>opportunities</strong> with <strong>the</strong> greatest potential and foster an entrepreneurial m<strong>in</strong>dset<br />

with a strong focus on life-skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. The provision of f<strong>in</strong>ancial services <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>rural</strong> youth <strong>in</strong> Sierra Leone is ano<strong>the</strong>r pioneer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiative (see box).<br />

9

The Rural F<strong>in</strong>ance and Community Improvement<br />

Programme, Sierra Leone<br />

The objective of this <strong>in</strong>itiative is to help <strong>the</strong> <strong>rural</strong> poor, especially<br />

youth, ga<strong>in</strong> access to f<strong>in</strong>ancial services by establish<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>ancial<br />

services associations. Each <strong>for</strong>mally registered association enables<br />

<strong>rural</strong> communities to access a comprehensive range of f<strong>in</strong>ancial<br />

services. It capitalizes on <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mal local rules, customs,<br />

relationships, local knowledge and solidarity, while <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>for</strong>mal bank<strong>in</strong>g concepts and methods. The current associations<br />

are wholly managed by <strong>young</strong> people. Each association has a<br />

manager and a cashier selected by <strong>the</strong> programme from <strong>the</strong> local<br />

community.<br />

Human capital-basic education<br />

Nearly 140 million youth <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries are classified as „illiterate‟. More<br />

generally, <strong>the</strong> preparation of <strong>rural</strong> youth <strong>for</strong> productive work is poor (see<br />

Atchorarena and Gasper<strong>in</strong>i, 2009). Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> 2007 World Development<br />

Report, „chang<strong>in</strong>g circumstances‟ mean that much greater attention needs to be<br />

given to <strong>the</strong> human capital needs of youth. These <strong>in</strong>clude „new health risks, <strong>the</strong><br />

chang<strong>in</strong>g nature of politics and <strong>the</strong> growth of civil society, globalisation and new<br />

technologies, expansion <strong>in</strong> access to basic education, and <strong>the</strong> ris<strong>in</strong>g demand <strong>for</strong><br />

workers with higher education‟.<br />

There is no simple, direct l<strong>in</strong>k between education and employment. However, <strong>the</strong><br />

best way to improve <strong>the</strong> <strong>future</strong> employment and livelihood prospects of<br />

disadvantaged <strong>young</strong> people <strong>in</strong> both <strong>rural</strong> and urban areas is to ensure that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

stay <strong>in</strong> school until <strong>the</strong>y are least functionally literate and numerate. Expand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

girl‟s education is <strong>the</strong> most obvious lever to change <strong>the</strong> situation of <strong>young</strong><br />

women. In <strong>the</strong> majority of low-<strong>in</strong>come develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, however, <strong>rural</strong><br />

youth still do not acquire <strong>the</strong>se basic competencies. In Ethiopia, <strong>for</strong> example,<br />

nearly three-quarters of 15-24 year olds have no school<strong>in</strong>g. In SSA and South<br />

Asia more than one-third of youth were still classified as illiterate <strong>in</strong> 2002. The<br />

availability of primary school<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas is improv<strong>in</strong>g rapidly <strong>in</strong> many<br />

countries, but <strong>the</strong> quality of education rema<strong>in</strong>s generally very low and is even<br />

decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> some countries.<br />

There are also major concerns about <strong>the</strong> relevance of school<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas.<br />

Curricula are criticised <strong>for</strong> not adequately prepar<strong>in</strong>g children <strong>for</strong> productive <strong>rural</strong><br />

lives and, worse still, fuel youth aspirations to move to urban areas. Calls persist<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> vocationalisation of school<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas, despite <strong>the</strong> fact that previous<br />

<strong>in</strong>itiatives to do so have failed <strong>in</strong> most countries <strong>for</strong> both supply and demand-side<br />

reasons. Governments and o<strong>the</strong>r providers should, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, focus on deliver<strong>in</strong>g<br />

reasonable quality basic education. The current push <strong>for</strong> eight years of universal<br />

basic education <strong>in</strong> most countries means that most children will not complete<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir school<strong>in</strong>g until <strong>the</strong>y are 15-16 years old.<br />

Given <strong>the</strong> endemic problems of <strong>rural</strong> school<strong>in</strong>g with high drop-out rates, support<br />

<strong>for</strong> non-<strong>for</strong>mal education programmes has <strong>in</strong>creased considerably dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> last<br />

decade. For example, Morocco‟s Second Chance schools target 2.2 million<br />

children between 8 and 16 years old who have never attended school or have not<br />

10

completed <strong>the</strong> full primary cycle. More than three-quarters of this group live <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>rural</strong> areas and about 45 per cent are girls. The Bangladesh Rural Advancement<br />

Committee model of non-<strong>for</strong>mal education is now be<strong>in</strong>g replicated <strong>in</strong> number of<br />

countries, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g several <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa.<br />

Human capital-skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

The <strong>rural</strong> world is chang<strong>in</strong>g rapidly <strong>in</strong> most countries. Rural youth must,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, be equipped with <strong>the</strong> requisite skills to exploit new <strong>opportunities</strong>.<br />

However, <strong>the</strong> provision of good quality post-school skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (both preemployment<br />

and job-related) rema<strong>in</strong>s very limited <strong>in</strong> most <strong>rural</strong> areas. The key<br />

issue <strong>in</strong> many countries is that national vocational tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g systems have been<br />

unable to deliver good quality and cost-effective tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to large numbers of<br />

both school leavers and <strong>the</strong> currently employed. It is essential, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, that all<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is based on precise assessments of job <strong>opportunities</strong> and skill<br />

requirements.<br />

Many governments would like to establish extensive networks of <strong>rural</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutions, but do not have <strong>the</strong> necessary resources to do this. Most evaluations<br />

have found that <strong>the</strong> cost-effectiveness of youth-related <strong>rural</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is generally<br />

low (Middleton et al, 1993 and Bennell, 1999). Typically, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g services are<br />

fragmented and <strong>the</strong>re is no coherent policy framework to provide <strong>the</strong> basis of a<br />

pro-poor <strong>rural</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g system. There are some notable exceptions, ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong><br />

South America – <strong>for</strong> example, <strong>the</strong> countrywide <strong>rural</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

support organization, SENAR, <strong>in</strong> Brazil.<br />

The key challenges <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g high-quality tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and extension services <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>rural</strong> youth are low educational levels, poor learn<strong>in</strong>g outcomes, scattered<br />

populations, low effective demand (from both <strong>the</strong> self-employed and employers),<br />

and limited scope <strong>for</strong> cost-recovery. Church organizations and NGOs have<br />

supported much of <strong>the</strong> vocational tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> school leavers <strong>in</strong> many<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, but fund<strong>in</strong>g constra<strong>in</strong>ts have resulted <strong>in</strong> significantly<br />

reduced enrolments <strong>in</strong> many countries dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> last decade. The stigma<br />

attached to vocational and technical education is ano<strong>the</strong>r major issue <strong>in</strong> most<br />

countries. Poor employment outcomes are a common weakness of <strong>rural</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

programmes. For example, about one-half of <strong>the</strong> <strong>young</strong> people who participated<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> India-wide Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of Rural Youth <strong>for</strong> Self-Employment have been unable<br />

to f<strong>in</strong>d employment. However, some tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiatives have been very<br />

successful. Farmer Field Schools <strong>in</strong> east Africa and <strong>the</strong> Fundacion Paraguaya are<br />

notable examples (see boxes). In Uganda, <strong>the</strong> Programme <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Promotion of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Welfare of Children and Youth has provided good quality tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, particularly<br />

<strong>in</strong> remote <strong>rural</strong> and war affected areas. Colombia and Nicaragua also have<br />

successful <strong>rural</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programmes <strong>for</strong> youth.<br />

The capacity of service providers to support <strong>rural</strong> clienteles, especially <strong>rural</strong><br />

youth, <strong>in</strong> all key sectors – such as education, health, polic<strong>in</strong>g, justice, <strong>rural</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>frastructure and agricultural extension – needs to be streng<strong>the</strong>ned significantly<br />

<strong>in</strong> most countries, which has major implications <strong>for</strong> higher education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

systems. Agricultural education at all levels also needs to be revitalized.<br />

11

Farmer Field Schools <strong>in</strong> East Africa<br />

FAO, o<strong>the</strong>r UN agencies and NGOs are support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

establishment of Farmer Field Schools <strong>in</strong> East Africa. The schools<br />

comb<strong>in</strong>e FAO‟s popular Farmer Field School teach<strong>in</strong>g methodology,<br />

which is designed to teach adult farmers about <strong>the</strong> ecology of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

fields through firsthand observation and analysis, and <strong>the</strong> Farmer<br />

Life School, which uses similar analytical techniques to teach<br />

human behaviour and AIDS prevention.<br />

A recently conducted comprehensive impact evaluation of Farmer<br />

Field Schools <strong>in</strong> Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda by a team from <strong>the</strong><br />

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) concluded that<br />

participation <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong>come by 61 per cent across <strong>the</strong> three<br />

countries as a whole. The most significant change was <strong>for</strong> crop<br />

production <strong>in</strong> Kenya (80 per cent <strong>in</strong>crease) and <strong>in</strong> Tanzania <strong>for</strong><br />

agricultural <strong>in</strong>come (more than a 100 per cent <strong>in</strong>crease). The ma<strong>in</strong><br />

reason <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>se positive impacts is that adoption of new<br />

agricultural technologies and <strong>in</strong>novations is significantly higher<br />

among farmers who attend <strong>the</strong> schools. Ano<strong>the</strong>r key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g is that<br />

<strong>young</strong>er farmers are more likely to participate <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> schools than<br />

older farmers <strong>in</strong> all three countries and that female-headed<br />

households benefited significantly more than male-headed<br />

households <strong>in</strong> Uganda (Davis, 2009).<br />

The San Francisco Agricultural School <strong>in</strong> Paraguay<br />

The San Francisco Agricultural School is run by <strong>the</strong> Fundacion<br />

Paraguaya. The school‟s curriculum comb<strong>in</strong>es <strong>the</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

traditional high-school subjects and technical skills with <strong>the</strong><br />

runn<strong>in</strong>g of 17 small-scale <strong>rural</strong> enterprises, most of which are<br />

based on <strong>the</strong> school‟s campus. All enterprises are strictly based on<br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g market demands and, <strong>for</strong> this reason, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>come<br />

generated from <strong>the</strong>m covers all <strong>the</strong> runn<strong>in</strong>g costs of <strong>the</strong> school,<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g teacher salaries and depreciation. All of its students are<br />

productively engaged ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> wage employment or selfemployment<br />

with<strong>in</strong> four months of graduation. Teacher<br />

accountability is very high because <strong>the</strong>ir own salaries are directly<br />

dependent on <strong>the</strong> immediate success of <strong>the</strong> school‟s enterprises<br />

(ILO, 2008).<br />

Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and capacity-build<strong>in</strong>g activities now comprise an important component<br />

of <strong>IFAD</strong>-supported activities and absorb up to 30 per cent of resources <strong>in</strong> some<br />

projects. S<strong>in</strong>ce key target groups are often illiterate or have little <strong>for</strong>mal<br />

school<strong>in</strong>g, this presents additional challenges <strong>for</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g effective tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. A<br />

good example of <strong>IFAD</strong> support <strong>in</strong> this area is <strong>the</strong> Skills Enhancement <strong>for</strong><br />

Employment Project <strong>in</strong> western Nepal, which targets Dalit and o<strong>the</strong>r seriously<br />

disadvantaged <strong>rural</strong> youth. The project has an ambitious goal of ensur<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

70 per cent of all tra<strong>in</strong>ees are <strong>in</strong> productive employment after six months. The<br />

project is implemented by ILO and is based on <strong>the</strong> ILO‟s Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> Economic<br />

Empowerment methodology, which is firmly rooted <strong>in</strong> participatory plann<strong>in</strong>g<br />

12

approaches and market-driven enterprise development. The Prosperer project <strong>in</strong><br />

Madagascar is ano<strong>the</strong>r good example of a new generation of youth-oriented<br />

projects be<strong>in</strong>g funded by <strong>IFAD</strong>. It seeks to improve <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>come of disadvantaged,<br />

poor youth <strong>in</strong> three regions of <strong>the</strong> country by provid<strong>in</strong>g diversified <strong>in</strong>comegenerat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>opportunities</strong> and promot<strong>in</strong>g entrepreneurship <strong>in</strong> <strong>rural</strong> areas. A total<br />

of 8,000 <strong>young</strong> people will be supported over <strong>the</strong> next five years.<br />

Access to land and natural resources and land tenure security lie at <strong>the</strong> heart of<br />

all <strong>rural</strong> societies and agricultural economies and are central to <strong>rural</strong> poverty<br />

eradication. Grow<strong>in</strong>g populations, decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g soil fertility and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g<br />

environmental degradation, <strong>the</strong> HIV/AIDS pandemic and new <strong>opportunities</strong> <strong>for</strong><br />

agricultural commercialisation, have all heightened demands and pressures on<br />

land resources and placed new pressures on land tenure systems, often at <strong>the</strong><br />

expense of <strong>the</strong> poor and vulnerable groups such as women and youth. In many<br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g countries <strong>in</strong>heritance rema<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> means <strong>for</strong> <strong>young</strong> people to<br />

access land. Typically, though, it is sons who <strong>in</strong>herit land, and daughters only<br />

ga<strong>in</strong> access to land through marriage. Ongo<strong>in</strong>g sub-division of land through<br />

<strong>in</strong>heritance has resulted <strong>in</strong> fragmented and unviable land parcels and<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>the</strong> youth are becom<strong>in</strong>g landless. The HIV/AIDS pandemic has<br />

resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g land grabb<strong>in</strong>g of widows‟ and orphans‟ lands by male<br />

relatives of <strong>the</strong> deceased, particularly <strong>in</strong> Africa. Increas<strong>in</strong>g landlessness amongst<br />

<strong>the</strong> youth has resulted <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ter-generational conflicts over land.<br />

Last<strong>in</strong>g solutions to land tenure <strong>in</strong>security of <strong>the</strong> youth could <strong>in</strong>clude: <strong>the</strong><br />

streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of legislation and legal services to women and youth <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

recognize and defend <strong>the</strong>ir rights to land; <strong>the</strong> development of land markets as<br />

mechanisms <strong>for</strong> access<strong>in</strong>g land; and perhaps most importantly, <strong>the</strong> identification<br />

and promotion of off-farm economic activities that target <strong>the</strong> youth.<br />

Young people tend to view agriculture as an unsatisfactory option unless <strong>the</strong>y<br />

have secure control over family lands. In Tanzania, as part of <strong>the</strong> national action<br />

plan <strong>for</strong> youth employment, labour <strong>in</strong>tensive <strong>rural</strong> <strong>in</strong>frastructure development<br />

has been actively supported among youth groups <strong>in</strong> „green belts‟ around major<br />

urban centres. The programme has also supported youth to own land by<br />

allocat<strong>in</strong>g areas <strong>for</strong> youth <strong>in</strong>frastructure development and enact<strong>in</strong>g laws to<br />

protect youth from discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> leas<strong>in</strong>g land.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ancial capital - micro-f<strong>in</strong>ance and enterprise development<br />

As <strong>the</strong> 2005 World Youth Report po<strong>in</strong>ts out „entrepreneurship is not <strong>for</strong> everyone<br />

and so cannot be viewed as a large-scale solution to <strong>the</strong> youth employment<br />

crisis‟ (p.59). None<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong>re is grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> targeted provision of<br />

micro-f<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>for</strong> youth, because it is recognized that, education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g do<br />

not on <strong>the</strong>ir own usually lead to susta<strong>in</strong>able self-employment. To date, however,<br />

services <strong>in</strong> this area rema<strong>in</strong> limited. Numerous problems have been encountered<br />

<strong>in</strong> pilot projects. The lack of control of loans by youth borrowers is a major issue,<br />

screen<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms are weak, and <strong>in</strong>tensive tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is needed <strong>in</strong> how to<br />

make best use of <strong>the</strong> money. Youth, and especially <strong>the</strong> very poor, are also<br />

frequently reluctant to borrow money. Integrated packages of <strong>in</strong>puts (credit,<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, advisory support, o<strong>the</strong>r facilities) are often necessary, but this imposes<br />

major demands on organisations and significantly reduces <strong>the</strong> number of<br />

beneficiaries. Agricultural and enterprise development extension staff should be<br />

much tra<strong>in</strong>ed to work with <strong>young</strong> people.<br />

13

The recent experience of <strong>the</strong> Population Council with micro-credit schemes <strong>for</strong><br />

youth highlights <strong>the</strong> overrid<strong>in</strong>g importance of specific contextual factors <strong>in</strong><br />

determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g outcomes and impacts. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, what works <strong>in</strong> one place<br />

may fail completely <strong>in</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r (Am<strong>in</strong>, 2010). One of <strong>the</strong> largest youth credit<br />

schemes is currently be<strong>in</strong>g funded by <strong>IFAD</strong> <strong>in</strong> Chongq<strong>in</strong>g Prov<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a,<br />

where more than 100,000 returned migrant workers have been provided with<br />

microf<strong>in</strong>ance and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> order to start a variety of agricultural and <strong>rural</strong><br />

enterprises.<br />

<strong>IFAD</strong> provides substantial support <strong>for</strong> non-farm enterprise development, but<br />

most projects <strong>in</strong> this area have not (at least until very recently) had any specific<br />

focus on <strong>rural</strong> youth. None<strong>the</strong>less, youth have benefited from <strong>the</strong>se<br />

<strong>in</strong>terventions. The success of what has become a national network of village<br />

banks <strong>in</strong> Ben<strong>in</strong> is a good example. Similarly, as part of <strong>the</strong> <strong>IFAD</strong>-funded <strong>rural</strong><br />

enterprise project <strong>in</strong> Rwanda, 60 per cent of <strong>the</strong> 3,500 <strong>young</strong> people who<br />

completed six-month apprenticeships ei<strong>the</strong>r started <strong>the</strong>ir own enterprises or<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ued to work as full-time employers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> enterprise where <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

apprenticed. In Uganda, <strong>IFAD</strong> (through <strong>the</strong> Belgian Survival Fund) provided<br />

US$ 3 million fund<strong>in</strong>g between 2000 and 2004 to <strong>the</strong> development programme of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Uganda Women‟s Ef<strong>for</strong>t to Save Orphans (UWESO). Loans were made to<br />

7,000 households with AIDS orphan members, with an overall loan recovery rate<br />

of 95 per cent. In addition, 655 orphans were tra<strong>in</strong>ed as artisans. However, as is<br />

<strong>in</strong>variably <strong>the</strong> case with project-elated tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g activities, <strong>in</strong>sufficient data is<br />

available about <strong>the</strong> subsequent employment activities of <strong>the</strong>se tra<strong>in</strong>ees to be<br />

able to reach firm conclusions about <strong>the</strong> cost-effectiveness of this tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Public employment generation<br />

Rural public works programmes are substitutes <strong>for</strong> unemployment benefit or<br />

<strong>in</strong>come support systems <strong>in</strong> countries that cannot af<strong>for</strong>d such systems. If properly<br />

designed, <strong>the</strong>y can per<strong>for</strong>m <strong>the</strong> role of a guaranteed employment scheme <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

disadvantaged of all ages and <strong>the</strong>y can be used to identify self-select<strong>in</strong>g groups<br />

of <strong>young</strong> workers who are most <strong>in</strong> need. However, a key conclusion of <strong>the</strong> World<br />

Bank Youth Inventory study is that “few public works programmes targeted on<br />

youth seem to lead to high employment chances <strong>for</strong> participants.”<br />

Employment creation <strong>for</strong> <strong>rural</strong> youth <strong>in</strong> NENA<br />

Sizeable enterprise development projects <strong>for</strong> <strong>young</strong> people are<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g funded by <strong>IFAD</strong> <strong>in</strong> Egypt and Syria. In Egypt, <strong>the</strong> focus is<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ly on agro-process<strong>in</strong>g and market<strong>in</strong>g activities <strong>in</strong> key<br />

high-value and organic agricultural export sectors. Private banks<br />

will manage loans and close l<strong>in</strong>ks will be established with<br />