Perle Fine - Abstract Critical

Perle Fine - Abstract Critical

Perle Fine - Abstract Critical

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

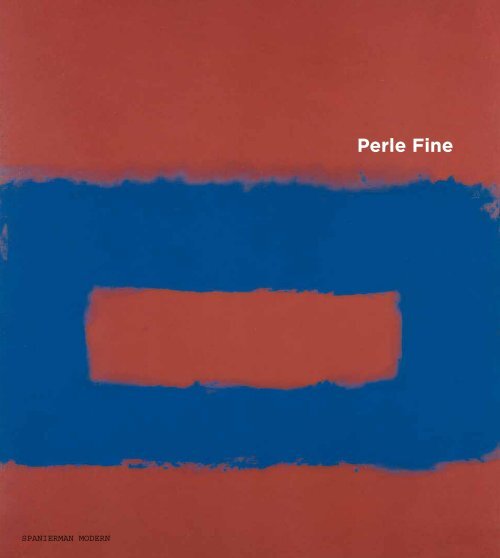

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong><br />

A

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> in her studio, Springs, New York, 1962.<br />

Front cover: Cool Series, (Blue over Red), p. 22.<br />

Opposite: Cool Series, (Plum over Pink), p. 31.<br />

All photographs of the artist by<br />

Maurice Berezov © A. E. Artworks, unless otherwise noted.<br />

Published in the United States of America in 2011 by<br />

Spanierman Modern, 53 East 58th Street, New York, NY 10022<br />

Copyright © 2011 Spanierman Modern<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,<br />

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by<br />

any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or<br />

otherwise, without prior permission of the publishers.<br />

isbn 978-1-935617-13-6<br />

Photography: Roz Akin<br />

Design: Amy Pyle, Light Blue Studio<br />

B

The Cool Series

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> in her studio, Springs, New York, 1962.

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> The Cool Series<br />

curated by christine berry<br />

essay by lisa n. peters<br />

november 10 to december 10, 2011<br />

SPANIERMAN MODERN<br />

53 EAST 58TH STREET new york 10022 tel (212) 832-1400<br />

christineberry@spanierman.com<br />

www.spaniermanmodern.com

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> The Cool Series<br />

Out of revelation, which came<br />

about through endless probing,<br />

came revolution. All irrelevancies<br />

in my painting are eliminated to<br />

exact an explicit image resulting<br />

in a clarity that rings a bell-like<br />

awakening. There is more than<br />

meets the eye here. These<br />

simplified works do not intend<br />

to be hard-edge or soft-edge;<br />

the expression is more than<br />

merely chemical or optical—it is<br />

metaphysical. The economy of<br />

means somehow seemed necessary<br />

to secure the sensation of the<br />

expression of the existentialist<br />

in art.<br />

—<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> 1<br />

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> in her studio, New York City, 1965.<br />

4

From the time she began to exhibit her paintings<br />

in the 1940s, <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> (1905–1988) was in the<br />

midst of the maelstrom that characterized the<br />

New York art world, as radical aesthetic innovations and<br />

reversals occurred in rapid succession. 2 While joining in<br />

the dynamic spirit of the time, throughout the period that<br />

followed, <strong>Fine</strong> maintained a calm and steady objective: she<br />

was driven simply to keep painting and to meet the high<br />

standards she set for herself. She viewed every shift in her<br />

art as arising from “a deep-rooted need, a pictorial need,”<br />

which led to her diVerent stylistic phases. 3 Among these,<br />

her “Cool” series of 1961–63, featured in this exhibition,<br />

seem to stand apart from her career trajectory, representing<br />

a break from the <strong>Abstract</strong> Expressionist idiom of her earlier<br />

work. Nonetheless, she stated that the paintings were a<br />

“growth” rather than a “departure,” developing from “a<br />

need within the painting to express more.” 4 In this respect,<br />

they reveal an intriguing connection with the zeitgeist.<br />

Although she created them while living in relative isolation<br />

in the Springs, East Hampton, they can be associated with<br />

contemporary Color Field painting, in which artists stepped<br />

back from the soul-baring of action painting to let their<br />

images speak for themselves, representing what the critic<br />

Clement Greenberg described as a “new openness and<br />

clarity.” 5 This approach was well suited to <strong>Fine</strong>, who had<br />

an innate proclivity for reXection and analysis. At the same<br />

time, the name she gave to the series suggests her awareness,<br />

whether it was conscious at the time or not, that the word<br />

“cool” had come to characterize a new type of art, free<br />

from psychological self-examination, that could involve the<br />

viewer in a direct emotional and intellectual experience<br />

of a work of art purely through its color and space, which<br />

were vehicles of visceral, spiritual experience. 6<br />

Born in Boston, <strong>Fine</strong> grew up in nearby Malden,<br />

Massachusetts. Before Wnishing high school, she had<br />

decided on an art career, attending the School of Practical<br />

Art, Boston, where she studied illustration and graphic<br />

design. In about 1927–28, she moved to New York City,<br />

and in 1929, she enrolled at the Grand Central School of<br />

Art, taking classes in illustration and painting with Pruett<br />

Carter. Living in Greenwich Village, she absorbed the new<br />

art of the day, for which there were many opportunities at<br />

the time, including the Gallery of Living Art at Washington<br />

Square, Downtown Gallery, the American Contemporary<br />

Gallery, the Whitney Studio Gallery, the Whitney Studio<br />

Club, and the Museum of Modern Art—<strong>Fine</strong> was among<br />

those in attendance at the museum’s inaugural exhibition in<br />

November 1929. She sojourned in the following summer<br />

in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where she would return<br />

annually in the years ahead, joining the town’s lively art<br />

community. It was in Provincetown that her fellow student<br />

at the Grand Central School of Art, Maurice Berezov,<br />

proposed to her. They were married in September, and<br />

both then transferred to the Art Students League, where<br />

<strong>Fine</strong> focused her energies on Wne art. “What I found out<br />

very quickly was you can only be a painter and nothing else<br />

if you’re going to be a painter,” she recalled of this time. 7<br />

Thomas Hart Benton was a leading instructor at the<br />

league when <strong>Fine</strong> entered, but disliking his realist methods,<br />

she chose to work instead with Kimon Nicolaides, adhering<br />

to the approach of the author of the classic, posthumously<br />

published, The Natural Way to Draw (1941), who encouraged<br />

spontaneity and an academic approach to modeling the<br />

Wgure. Fellow Nicolaides student, James Brooks, developed<br />

a friendship with <strong>Fine</strong> that lasted in the years ahead. At<br />

the time, the art of Cézanne was compelling to <strong>Fine</strong>, and<br />

through studying his canvases, she gained an appreciation<br />

for the way he created a kind of order from nature and<br />

took control of the canvas, forming images which were at<br />

one with their space. 8<br />

As the Depression descended, <strong>Fine</strong>, like so many of<br />

her artist-cohort, found it diYcult to aVord art school<br />

tuition, but she was less impacted than most because she<br />

was able to work independently in her studio on the<br />

aesthetic challenges she set for herself. In 1933, when<br />

Hans Hofmann moved his hugely popular Munich art<br />

school to New York, <strong>Fine</strong> and Berezov became part of<br />

it. Operating his classes like those of a Parisian atelier,<br />

Hofmann taught by example, and <strong>Fine</strong> and her fellow<br />

students were enthralled by his teachings and personality.<br />

“No teacher I have ever known engendered as much love<br />

and loyalty from his students,” <strong>Fine</strong> recalled, noting how<br />

her classmates hung on his every word, even when his<br />

thick accent made it diYcult to understand him. 9 Among<br />

those at the school when <strong>Fine</strong> attended were Larry<br />

Rivers, Robert De Niro, and Lee Krasner, who became a<br />

5

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> (center) and Hans Hofmann in Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1940s.<br />

lifelong friend. <strong>Fine</strong> and Berezov also attended Hofmann’s<br />

summer school in Provincetown.<br />

Because Hofmann’s school in New York was across<br />

the street from <strong>Fine</strong>’s studio, she was able to drop in at will<br />

when she needed direction. What she valued in Hofmann’s<br />

instruction was that “he combined the Xat two-dimensional<br />

with a strong feeling for the three-dimensional in volume,<br />

with movement, and a great deal of expression.” 10 However,<br />

for <strong>Fine</strong>, Hofmann’s role was primarily that of an “opening<br />

wedge,” providing a means by which she was able to form<br />

her own artistic identity. She later stated that Hofmann<br />

might have enjoyed her nonobjective work, but she could<br />

not have done it in his class. 11<br />

<strong>Fine</strong> applied to the Works Progress Administration<br />

for a job, but was turned down, according to her, because<br />

she “had a telephone.” Quietly creating abstract works on<br />

her own while Regionalism and Social Realism prevailed,<br />

she seems to have only participated in one exhibition<br />

during the 1930s, a show held in August 1938 at the<br />

Municipal Art Galleries, where her “prismatic still-life”<br />

was given recognition by the New York Times. 12<br />

After the war, the climate of the art world changed<br />

direction, as abstract art gained prominence once again,<br />

inXuenced by the arrival in New York of many European<br />

artist-émigrés escaping the horrors abroad. In 1943, <strong>Fine</strong><br />

began to earn recognition when she received a grant<br />

from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and<br />

participated in exhibitions at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of<br />

this Century Gallery and the Museum of Nonobjective<br />

Painting (now, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New<br />

York), which was under the directorship of Hilla Rebay.<br />

<strong>Fine</strong>’s contributions to the museum show were singled out<br />

by the press. Related in their movement to the mobiles<br />

of Alexander Calder, they were described as “precise and<br />

delicate” by a reviewer for Artnews, while Edward Alden<br />

Jewell commented in the New York Times that they were<br />

“much more original” than those of other artists who were<br />

under the spell of Kandinsky and “quite charming, too.” 13<br />

In 1945, <strong>Fine</strong> joined American <strong>Abstract</strong> Artists, a<br />

context in which she came to know many leading abstract<br />

artists of the day including Josef Albers, Fannie Hillsmith,<br />

Ibram Lassaw, I. Rice Pereira, and Ad Reinhardt—she<br />

had a particular admiration for Reinhardt, whose bravery<br />

she found inspiring. 14 In the same year, <strong>Fine</strong>’s Wrst solo<br />

exhibition took place; it was held at the Willard Gallery<br />

on East 57th Street in February–March and was widely<br />

reviewed in the press. Many saw a connection between<br />

her work and that of Joan Miró, due to her depiction<br />

of organic forms in motion that expressed a variety of<br />

moods. 15 Within the year, <strong>Fine</strong> moved her aYliation<br />

across the street to the gallery of Karl Nierendorf, who<br />

had specialized in the Blaue Reiter group in Germany. 16<br />

Nierendorf provided <strong>Fine</strong> with a stipend and held shows<br />

of her art in 1946 and 1947. The New York Times called<br />

<strong>Fine</strong>’s work, on view in 1946, “inventive and eclectic,”<br />

noting that it demonstrated inXuences as disparate as<br />

Léger, Mondrian, Duchamp, Klee, and Miró while<br />

revealing a personal style that “promises less divisible<br />

triumphs to come.” 17 In an article in Arts & Architecture<br />

in 1947, Benjamin Baldwin stated:<br />

6

To <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>, modern art is a conscious art and a very complicated<br />

phenomenon. It demands that the artist have erudition and at the<br />

same time ease of execution. This can come about only with a<br />

thorough knowledge and constant practice of the laws of painting,<br />

enriched by experiencing the beauty and drama in nature, the<br />

poetry and magic of color. . . . The canvas dictates what is wanted<br />

here, needed there. From then on the artist explores, builds, destroys,<br />

builds anew. Finally the image—strange, mysterious—emerges,<br />

oVering us new and delightful passage into another world. 18<br />

In 1947, <strong>Fine</strong> was given an unusual assignment. She<br />

was asked by the collector Emily Hall Tremaine, who<br />

had acquired works by <strong>Fine</strong>, to make an exact copy of<br />

Piet Mondrian’s diamond-shaped Victory Boogie-Woogie,<br />

then in Tremaine’s collection (now in the collection of<br />

the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague) as well as to prepare<br />

a complete analysis of the painting, on which the artist<br />

had been working when he died three years earlier. <strong>Fine</strong>,<br />

who had come to know Mondrian after he emigrated<br />

to America in 1940, found him personally sweet and felt<br />

a deep reverence for his achievement. She later stated:<br />

“I don’t think we’ll ever realize how important was<br />

Mondrian’s inXuence and what he had to say in the<br />

history of art.” 19 <strong>Fine</strong> executed her copy under the same<br />

conditions in which Mondrian had painted his original,<br />

working in a pure white room and using brushes and<br />

paints identical to his. Although in most of <strong>Fine</strong>’s work,<br />

Mondrian’s inXuence is not obviously apparent, due to<br />

him, she felt enduringly conscious of the vertical and<br />

horizontal and their universal implications; in her oeuvre,<br />

this awareness emerged most fully in her Cool series.<br />

After Nierendorf’s sudden death due to a heart attack<br />

in 1947, <strong>Fine</strong> began to be represented by Betty Parsons,<br />

whose gallery (opened in September of the year), had<br />

become the leading showplace in New York for the newest<br />

art of the day. 20 As such, the gallery played a critical role<br />

in the rise of the New York School and the <strong>Abstract</strong><br />

Expressionist movement. From 1947 through 1953, when<br />

<strong>Fine</strong> was represented by Parsons, the gallery exhibited<br />

the work of Hofmann, Barnett Newman, Pollock,<br />

Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, ClyVord Still, and many other<br />

prominent artists. <strong>Fine</strong> befriended Rothko and Newman<br />

in the context of Parsons’s gallery. She recalled having a<br />

drink with Rothko on the occasion of his Wrst show in<br />

Willem de Kooning and <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> at Wilfrid Zogbaum’s studio,<br />

Springs, New York, 1950s.<br />

1948, at which she helped to calm his “nervousness and<br />

excitement.” 21 Parsons, who was more willing than many<br />

other mid-century dealers to give shows to women artists,<br />

exhibited <strong>Fine</strong>’s work three times: in 1949, 1951, and<br />

1952–53. In his article in the New York Times reviewing<br />

<strong>Fine</strong>’s Wrst Parsons show in 1949, Howard Devree chose to<br />

illustrate her painting Summer Studio and stated that <strong>Fine</strong><br />

organized “her canvases well, using color and form in a<br />

nice blend and achieving a spatial sense that is distinctive<br />

and convincing.” 22 Of <strong>Fine</strong>’s last show at the gallery,<br />

Devree waxed:<br />

In her recent paintings at the Betty Parsons Gallery, <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong><br />

carries further her “pure” painting. An exact and sensitive colorist,<br />

she employs color shapes rather than forms in engaging and<br />

persuasive tonal eVects which sometimes seem to employ almost<br />

impalpable planes of color and hinted at rather than realized spatial<br />

arrangements. An English critic once said that prose was heard<br />

and poetry overheard; and Miss <strong>Fine</strong>’s “Prescience” and “Tyranny<br />

of Space” leaves this reporter feeling as if he had dropped in on a<br />

pensive soliloquy translated in terms of color. In that experimental<br />

world of the non-Wgurative, her statements are all sensitive, sure,<br />

and highly personal. 23<br />

7

<strong>Fine</strong> was aYliated with Parsons when the artists’<br />

organization, known simply as The Club, came into being.<br />

It was formed in the fall of 1949 in the studio of Ibram<br />

Lassaw, and <strong>Fine</strong> was among few women to become part<br />

of it, joining it at its inception. <strong>Fine</strong> was invited to be a<br />

member by Willem de Kooning. She recalled: “I met Bill<br />

on the street. He started to talk about the beginning of<br />

The Club, and would I join I said I’d be delighted to. You<br />

know, we all wanted a place to go to. It wasn’t always the<br />

best thing to go to someone’s studio for one reason<br />

or another. So they started The Club.” 24 <strong>Fine</strong> solidiWed<br />

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> and Ad Reinhardt during a photo shoot for an exhibition, 1951.<br />

her friendships with Reinhardt, Franz Kline, and Elaine<br />

and Willem de Kooning through her participation in<br />

The Club.<br />

In 1954, <strong>Fine</strong> and Berezov built a one-room studio<br />

house in the woods in Springs, East Hampton, an area<br />

where they had often spent time previously while visiting<br />

with Krasner and Pollock. Due to his advertising job in<br />

the city on Madison Avenue, Berezov could only visit on<br />

weekends, but <strong>Fine</strong> remained in Springs throughout the<br />

year, although she traveled into the city on occasion to<br />

see art and to hang her works in exhibitions. In Springs,<br />

<strong>Fine</strong> enjoyed her solitude and being able to work steadily<br />

on her own. Nonetheless, she also associated with artists<br />

who were part of the growing artists’ community, such<br />

as the de Koonings, Ernestine and Ibram Lassaw, Ad and<br />

Rita Reinhardt, Rae and John Ferren, and Krasner and<br />

Pollock (until his death in 1956). One visit from Willem de<br />

Kooning stood out for <strong>Fine</strong>. She remembered a day when<br />

he came into her studio: “He made some nice remarks<br />

about the paintings and said: ‘But this is all out of doors.<br />

It’s what you see out here, isn’t it You know, through a<br />

big studio window.’ And I said, ‘Well, yes, I guess so if you<br />

say so.’ Of course it wasn’t . . . . But to what extent that<br />

had impressed itself upon me I don’t know. You know,<br />

sometimes the very black trunks of trees against the white<br />

snow and horizon lines. Certainly there is something very<br />

exciting about the country.” 25 This encounter was the<br />

point at which, unknowingly, <strong>Fine</strong> had begun what would<br />

be her Cool series.<br />

It had no doubt been just a short time before this that<br />

<strong>Fine</strong>, in preparation for her second exhibition at Graham<br />

Gallery (scheduled for April of 1963), took the radical<br />

step of destroying a show’s worth of her work. Yet, <strong>Fine</strong><br />

retained the purely black and white painting observed<br />

by de Kooning, deciding to forgo the color and diagonal<br />

lines she had been planning to add to it. She recalled:<br />

“what remained was the rectangle that I used immediately<br />

in the next several paintings that I made and one that<br />

I made in black and white which is sort of an inverted<br />

rectangle like that I call the Big U.” 26 <strong>Fine</strong> was not in full<br />

agreement with de Kooning’s suggestion that the painting<br />

he observed reXected the landscape around her in Springs,<br />

but she felt that the Cool series that emerged did relate<br />

8

to her new life in the country. “The things in the city<br />

tend to be more cerebral,” she noted, “and in the country<br />

freer in color somehow and in form as well.” She found<br />

the country “more open and more relaxed,” by contrast<br />

with the city where “you become more introverted.” She<br />

explained that she called her new paintings, the Cool series<br />

because they did not impose feeling on the viewer, but<br />

were instead a pure expression of color and space. 27<br />

From 1961, until the opening of her show at Graham,<br />

<strong>Fine</strong> devoted her attention exclusively to the Cool series,<br />

in which she limited her imagery to rectangles and squares<br />

placed oV center on mostly monochromatic grounds.<br />

Of the change in her art, she declared: “Out of revelation,<br />

which came about through endless probing, came<br />

revolution.” She stated: “The economy of means somehow<br />

seemed necessary to secure the sensation of the expression<br />

of the existentialist in art.” 28<br />

While her paintings were on view at Graham, <strong>Fine</strong><br />

was interviewed on the radio by Irving Sandler, the<br />

noted art historian, art reviewer then for the New York<br />

Post, and chronicler of the <strong>Abstract</strong> Expressionist era. 29<br />

<strong>Fine</strong> stated to Sandler that the compositions of her new<br />

work had been “many years in the making,” as there had<br />

always been a strong horizontal-vertical basis in her art,<br />

despite her earlier stylistic adherence to action painting.<br />

She went on to note that her Cool series could be seen<br />

as an extension of the Neoplastic approach of Mondrian<br />

that she had long revered; in her use of straight lines, she<br />

observed that she sought to express constants in nature<br />

and a dynamic equilibrium that was universal. By avoiding<br />

the forty-Wve degree angle, she aYrmed her concurrence<br />

with Mondrian as to its instability and lack of repose and<br />

conveyed her view that the diagonal was unnecessary<br />

because the square and rectangle already implied its<br />

movement. <strong>Fine</strong> acknowledged that she was opposed to<br />

“simply painting air,” and further observed: “I don’t think<br />

that’s enough. I think the form that you limit yourself with<br />

finally oVers such an inWnite variety of expressions.” 30<br />

However, <strong>Fine</strong> moved away from Mondrian in the<br />

emotional range in her work, achieved through color and<br />

the variation in the edges of her lines. Sandler observed<br />

that she had departed from Mondrian’s unwavering<br />

primaries, using a palette that was “mixed, highly unstable,<br />

Above: Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> at Tanager Gallery, New York,<br />

for <strong>Fine</strong> show opening, 1958. Below: Mark Rothko and <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> at Tanager Gallery,<br />

New York, for <strong>Fine</strong> show opening, 1958.<br />

9

East Hampton artists at a beach picnic, 1962. Standing, left to right: Buffie Johnson, Lester Johnson, Howard Kanovitz, Fairfield Porter, Syd Solomon, Frederick Kiesler,<br />

Norman Bluhm, Emanuel Navaretta, and <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> (with hand on hip). Seated, left to right: unidentified, Lee Krasner (back to camera), Al Held, Mary Kanovitz, Balcomb<br />

Greene; middle row: John Little, Elaine de Kooning, James Brooks, Rae Ferren, Charlotte Park, Louis Schanker, Sylvia Stone, Ibram Lassaw, Theodoros Stamos, Jane Wilson,<br />

Jane Freilicher, Robert Dash; left from front center: David Porter, Adolph Gottlieb, John Ferren, Lucia Wilcox. Photograph by Hans Namuth. Courtesy Center for Creative<br />

Photography, University of Arizona © Hans Namuth Estate.<br />

volatile, and at times atmospheric.” 31 <strong>Fine</strong> concurred,<br />

stating her opinion that Americans had contributed to<br />

art in the previous Wfteen years “through this churning<br />

and this violent kind of thing.” To <strong>Fine</strong>, color was<br />

necessary to the expression of emotion and pointed out<br />

that her paintings at Graham included some that that were<br />

muted and introverted and others that were the opposite.<br />

Indeed, despite the structural similarities, each painting,<br />

through both color and form, reveals diVerent spatial and<br />

emotional qualities. In one, a yellow rectangle pushes<br />

forward from a rich russet ground, while in another, the<br />

deep brown rectangle sits back and the dusky orangered<br />

ground pulsates toward us. <strong>Fine</strong> also aVected mood<br />

through the subtleties in her brushwork. At times, the<br />

edges are crisp, creating a clear diVerentiation between<br />

shape and background, and bringing one or the other<br />

forward. At other times, the edge is softened, allowing a<br />

square to Xoat in the space. In some of the images, the<br />

ground tone varies, seeming to bleed out from the edges.<br />

Lawrence Campbell observed this aspect of the works in<br />

a review of the Graham exhibition in Artnews, writing:<br />

“Since each painting developed as it went along, [<strong>Fine</strong>] has<br />

loosely Xaked oV certain edges, allowing other planes to<br />

collide at Wrmly deWned limits, and allowed other colors to<br />

lap as though they were at sea at some eternal doorway.” 32<br />

In the Cool series, the position of the rectangles and<br />

squares in the compositions impact the way we read the<br />

space. Placed toward the lower edge of the canvas, the<br />

angular shape can seem to cut the picture plane, as in one<br />

of Barnett Newman’s zips, while the movement is at once<br />

centripetal, into the open window, and decentered,<br />

extend ing into the world beyond. As a result, the images<br />

10

create a sense of the meditative and peripheral at once.<br />

They are thus emotionally and spiritually absorbing, in<br />

the manner of a work by Rothko, yet analytical in their<br />

spatial ambiguity.<br />

Although <strong>Fine</strong> linked her viewpoint to that of<br />

Mondrian, the Cool series parallels the era’s gestalt, as the<br />

pendulum swung from the intense exposés of the artists’<br />

psyche that constituted <strong>Abstract</strong> Expressionist art to a<br />

type of painting in which the artist stepped back, letting<br />

the painting engage the viewer directly. Championing<br />

the new approach, Clement Greenberg named it “Post-<br />

Painterly <strong>Abstract</strong>ion,” so as to align it with the classical<br />

tradition; he was alluding to the recurring alternating<br />

pattern throughout art history of the classical (nonpainterly)<br />

and the baroque-romantic (painterly). The<br />

name Color Field is the one, however, that has come<br />

most commonly to describe this stylistic mode, present in<br />

works created from the 1950s until about 1970. 33 Cool, a<br />

word whose usage has shifted throughout the ages, was a<br />

concept Wtting to the new era and the new painting. In<br />

Color as Field: American Painting, 1950–1975 (2007), Karen<br />

Wilkin described this phenomena. She observed that<br />

although there are commonalities in Color Field works<br />

by artists such as Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis,<br />

Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski (such as a “primacy<br />

of color, frontality, spatial and emotional ambiguity, and a<br />

paradoxical ‘signature’ anonymity, with the deployment of<br />

surprising hues made to assume the burden of associative<br />

meaning”), they<br />

In his review of <strong>Fine</strong>’s Graham show in the New<br />

York Post, Sandler gave credence to the way <strong>Fine</strong> had<br />

gone forward from the art of the previous era to the new<br />

paradigm, stating:<br />

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>, showing at the Graham Gallery, has gathered up<br />

the “action” in her painting and concretized it into large and<br />

peaceful rectangles that Xoat upon evocative backgrounds of<br />

blue-violet, brown, green, and rose. It would seem that she has<br />

absorbed the ambiance of Kline and Rothko without assuming<br />

the former’s violent thrusts or the latter’s glowing suspensions.<br />

What emerges, instead, is an altogether surprising delicacy, a kind<br />

of poetic equilibrium—and this, despite the inherent energy<br />

characteristic of boldly painted squares or rectangles, or the stark<br />

economy of color. 35<br />

When <strong>Fine</strong> showed additional Cool series paintings at<br />

Graham in March of 1964, John Gruen wrote in the New<br />

York Herald Tribune:<br />

Miss <strong>Fine</strong> continues to explore the geometric shape as it occurs<br />

on a Xatly painted background—the colors creating tensions—the<br />

shapes assuming the function of expressive dividing lines that give<br />

way to other shapes, forming other sequences of expression. There<br />

is a vibrant light that emanates from these works, not blinding or<br />

jarring or dizzying. It is an arresting light that remains constant,<br />

lending purity—even dignity, to essentially emotional statements. 36<br />

are more distinguished by their “cool”—in Marshall McLuhan’s<br />

sense of the word—than by any obvious relation to <strong>Abstract</strong><br />

Expressionism. Louis’s, Noland’s, Olitski’s, and, to a degree,<br />

Frankenthaler’s otherwise diverse paintings, with their insubstantial<br />

surfaces and deliberately suppressed “handwriting,” all appear<br />

strikingly reticent, not only physically but also psychologically. . . .<br />

While scrupulously avoiding anything resembling psychological<br />

symbolism, the “post-painterly” conception of “cool” included<br />

the belief that a painting, no matter how apparently restrained,<br />

could address the viewer’s whole being—emotions, intellect, and<br />

all—through the eye, just as music did through the ear. . . What sets<br />

Color Field paintings apart is the extraordinary economy of means<br />

with which they manage not only to engage our feelings but also<br />

to ravish the eye. 34<br />

Lee Krasner and <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> at Ashawagh Hall Fair, Springs, New York, mid-1960s.<br />

11

Despite such perceptive commentaries and obvious<br />

respect from the critics, Graham was able to sell few of<br />

<strong>Fine</strong>’s Cool series paintings. Looking back, <strong>Fine</strong> was aware<br />

that this might have been because the paintings were<br />

ahead of their time. She stated in 1968 that they “preceded<br />

the things that are done today in this limited motif, so<br />

that some people were rather shocked that I should have<br />

arrived.” 36 Indeed, they predated Robert Motherwell’s<br />

“Open” series, begun in the late 1960s, and other<br />

similar subtly toned Color Field works by artists such as<br />

Larry Poons and Olitski of mid-decade. In their poetic<br />

equilibrium, their combination of restraint and emotional<br />

expressiveness, and their uniting of the classical and the<br />

romantic, <strong>Fine</strong>’s Cool series paintings are timeless and<br />

yet also seemingly relevant to today’s desire for a broader,<br />

calmer vision of the world.<br />

Lisa N. Peters, Ph.D.<br />

1. <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>, artist’s statement in Klaus Jurgen-Fischer, “Neue<br />

Abstraktion,” Das Kunstwerk 18 (April–June 1965). I would like to<br />

express gratitude to Maddy and David Berezov for providing materials<br />

from the Berezov Archives cited in this essay.<br />

2. For an extensive treatment of <strong>Fine</strong>’s career and context, see<br />

Kathleen L. Housley, Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> (New<br />

York: Midmarch Arts Press, 2005).<br />

3. Transcript of Tape-Recording of an Interview with <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> by Irving<br />

Sandler, Casper Citron Program, Station wrfm, New York, April 8,<br />

1963, Berezov Archives.<br />

4. Sandler interview.<br />

5. Clement Greenberg, Post Painterly <strong>Abstract</strong>ion, exh. cat. (Los Angeles<br />

County Museum of Art, 1964), cited in Karen Wilkin, Color as Field:<br />

American Painting, 1950–1975 (New Haven and London: American<br />

Federation of Arts in association with Yale University Press, 2007), 11.<br />

6. See Wilkin, 17.<br />

7. Oral History Interview with <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>, Conducted by Dorothy Seckler<br />

at the Artist’s Studio in New York, NY, January 19, 1968, Archives of<br />

American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.<br />

8. Seckler interview.<br />

9. Seckler interview.<br />

10. <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> and Maurice Berezov, The Teaching of Hans Hofmann,<br />

unpublished manuscript, Berezov Archives. Cited in Housley, 33.<br />

11. Seckler interview.<br />

12. Howard Devree, “Along Outward Trails,” New York Times,<br />

August 7, 1938.<br />

13. “The Passing Shows,” Artnews (August–September 1943);<br />

Edward Alden Jewell, “Melange of New Shows,” New York Times,<br />

October 24, 1943.<br />

14. Seckler interview.<br />

15. Maude Riley, “<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>,” Art Digest (March 1, 1945); Edward<br />

Alden Jewell, “<strong>Abstract</strong> Artists Open Display Here,” New York Times,<br />

March 14, 1945.<br />

16. The Guggenheim Foundation purchased Nierendorf’s estate in<br />

1948. Housed at the Guggenheim Museum, it includes works by Max<br />

Ernst, Adolph Gottlieb, Juan Gris, Paul Klee, Oscar Kokoschka, and<br />

Joan Miró. See: http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/<br />

about-the-collection/new-york/karl-nierendorf-estate/1650, retrieved<br />

September 2011. Information on Nierendorf may be found in Housley,<br />

88–93.<br />

17. Edward Alden Jewell, “Glances Backward and About,” New York<br />

Times, April 7, 1946.<br />

18. Benjamin Baldwin, “<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>,” Arts & Architecture (May 1947).<br />

19. Seckler interview.<br />

20. For Parsons, see Lee Hall, Betty Parsons: Artist, Dealer, Collector<br />

(New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991).<br />

21. Seckler interview.<br />

22. Howard Devree, “Vital and Diverse: New Current Group<br />

Exhibitions Stress Work by Contemporary Americans,” New York Times,<br />

June 5, 1949.<br />

23. Howard Devree, “In Various Veins,” New York Times, December 21,<br />

1952.<br />

24. Seckler interview.<br />

25. Seckler interview.<br />

26. Seckler interview.<br />

27. Seckler interview.<br />

28. <strong>Fine</strong>, artist’s statement, 1965.<br />

29. Sandler interview. Sandler went to write The Triumph of American<br />

Painting: A History of <strong>Abstract</strong> Expressionism (New York: Praeger, 1970)<br />

and The New York School: The Painters and Sculptors of the Fifties (New<br />

York: Harper & Row, 1978).<br />

30. Sandler interview.<br />

31. Sandler interview.<br />

32. L[awrence] C[ampbell], “Reviews and Previews: <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong><br />

[Graham; April 2–20],” Artnews (April 1963).<br />

33. See Wilkin, Color as Field.<br />

34. Wilkin, 17.<br />

35. Irving Sandler, “<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>,” New York Post, April 7, 1963.<br />

36. John Gruen, “In the Galleries: <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>,” New York Herald Tribune,<br />

March 7, 1964.<br />

37. Seckler interview.<br />

12

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> (1905–1988)<br />

museum collections<br />

Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts<br />

Arkansas Art Center, Little Rock<br />

Ball State Museum of Art, Muncie, Indiana<br />

Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts<br />

Brooklyn Museum, New York<br />

Cheekwood Botanical Garden and Museum of Art,<br />

Nashville, Tennessee<br />

Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C.<br />

Guild Hall, East Hampton, New York<br />

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University,<br />

Ithaca, New York<br />

Hofstra University Museum, Hempstead, New York<br />

Indianapolis Museum of Art<br />

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington<br />

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York<br />

Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, New York<br />

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.<br />

New York University Art Collection<br />

Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York<br />

Principia College, Saint Louis, Missouri<br />

Provincetown Art Association Museum, Massachusetts<br />

Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey<br />

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton,<br />

Massachusetts<br />

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.<br />

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York<br />

University of California, Berkeley<br />

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York<br />

Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina,<br />

Greensboro<br />

Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts<br />

selected solo exhibitions<br />

Marian Willard Gallery, New York, 1945<br />

Nierendorf Gallery, New York, 1946, 1947<br />

M.H. De Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco, 1947<br />

Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, 1949, 1951, 1952-3<br />

Tanager Gallery, New York, 1955, 1957, 1958, 1960<br />

Franklin Gallery, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 1961<br />

Robert Keene Gallery, Southampton, New York, 1961<br />

Graham Gallery, New York, 1961, 1963, 1964, 1967<br />

Joan Washburn Gallery, New York, 1972<br />

Andre Zarre Gallery, New York, 1973, 1976, 1977<br />

Hofstra University Museum, Hempstead, New York, 1974<br />

Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York, Major<br />

Works, 1954–1978: A Selection of Drawings, Paintings, and<br />

Collages, 1978.<br />

Ingber Gallery, New York, 1982, 1984<br />

Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>: Works on<br />

Paper, 1997<br />

Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, East Hampton,<br />

New York, <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> Collages, 1957–1966, 2005<br />

McCormick Gallery, Chicago, <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>: The Storm<br />

Departs, 2007<br />

Hofstra University Museum, Hempstead, New York,<br />

Tranquil Power: The Art of <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong>, 2009 (traveling<br />

exhibition)<br />

selected group exhibitions<br />

Municipal Art Galleries, New York, 1938<br />

Art of this Century, New York, Spring Salon, 1943, 1944<br />

The Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now, Solomon<br />

R. Guggenheim Museum), 1943, 1944, 1945, 1946, 1947<br />

Puma Gallery, New York, 1944<br />

Wittenborn Gallery, New York, 1944<br />

American <strong>Abstract</strong> Artists (AAA), 1945–1970s<br />

Art of this Century Gallery, New York, The Women, 1945<br />

Alumnae Hall Gallery, Western College, Oxford, Ohio,<br />

The Women: An Exhibition of Paintings by Contemporary<br />

Women, 1945<br />

Provincetown Art Association, Massachusetts, 1945–51<br />

Society of American Etchers, Thirty-First Annual<br />

Exhibition, 1946<br />

13

Whitney Museum of American Art, Annuals and Biennials,<br />

1946, 1947, 1951, 1952, 1954, 1955, 1958, 1961, 1972<br />

Musee d’Art Moderne, Paris, Salon des Réalités Nouvelles,<br />

1947, 1950<br />

Stanhope Gallery, Boston, Works on Paper, 1947<br />

Watkins Gallery, American University, Washington, D.C.,<br />

Spring Annual, 1947<br />

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut, Painting<br />

Toward Architecture, 1947<br />

Salon des Réalitiés Nouvelles, Paris, 1947, 1950<br />

Art Institute of Chicago, <strong>Abstract</strong> and Surrealist American<br />

Art, 1948<br />

Virginia Museum of <strong>Fine</strong> Arts, Richmond, Biennial, 1948<br />

(purchase prize)<br />

Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, New England<br />

Painting and Sculpture, 1949<br />

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (traveling<br />

exhibition to European museums), 1949<br />

Gallery 200, Provincetown, Massachusetts, Group<br />

Exhibition, 1949<br />

Tryon Gallery, Smith College, Northampton,<br />

Massachusetts, Ten Women Who Paint, 1949<br />

Hawthorn Memorial Gallery and the Provincetown Art<br />

Association, Massachusetts, Post-<strong>Abstract</strong> Painting 1950:<br />

France, America, 1950<br />

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, American Painting<br />

Today—1950, 1950<br />

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California,<br />

Contemporary Painting in the U.S., 1951<br />

Stable Gallery, 9th Street Show, 1951<br />

Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors, 1954, 1955,<br />

1957, 1958, 1962, 1964<br />

Stable Gallery, New York Annuals, 1953, 1954, 1955,<br />

1956, 1957<br />

Wittenborn, One-Wall Gallery, New York, Lithographs,<br />

1952<br />

Bennington College Gallery, Vermont, Nine Women Artists,<br />

1953<br />

New School for Social Research, New York, Painting and<br />

Sculpture, 1953<br />

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Selections of<br />

Painting and Sculpture, 1953<br />

Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York, Eleven<br />

New Artists of the Region, 1955<br />

Brooklyn Museum, New York, Ninth Annual Print<br />

Exhibition, 1955 (purchase award)<br />

American Federation of Arts, Contemporary Trends, 1955<br />

(traveling exhibition)<br />

Tanager Gallery, New York, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958, 1959,<br />

1960, 1961, 1962<br />

Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, Annuals, beginning<br />

1955<br />

Center Gallery, New York, 1956<br />

Kraushaar Galleries and the Brooklyn Museum, New York,<br />

14 Painter-Printmakers, 1957<br />

Signa Gallery, East Hampton, New York, A Review of the<br />

Season, 1957<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Nature in<br />

<strong>Abstract</strong>ion: The Relation of <strong>Abstract</strong> Painting and Sculpture to<br />

Nature in Twentieth-Century American Art, 1958 (traveling<br />

exhibition)<br />

Zabriskie Gallery, New York, Collage in America, 1958<br />

(in cooperation with the American Federation of Arts)<br />

Center Gallery, New York, 1958<br />

Carnegie Institute, Museum of Art, Pittsburgh<br />

International Exhibitions of Contemporary Painting and<br />

Sculpture, 1958, 1961<br />

Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York, Painters,<br />

Sculptors, Architects of the Region, 1959<br />

The Contemporary Arts Association of Houston, Texas,<br />

10th Street, 1959<br />

Bertha Schaefer Gallery, New York, Modern Drawing:<br />

European and American, 1959<br />

Signa Gallery, East Hampton, New York, A Review of the<br />

Season, 1959<br />

McNay Art Institute, San Antonio, Texas, 1960<br />

Brookhaven National Laboratory, Second Annual Art<br />

Exhibit, 1960<br />

Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, Mexican<br />

Biennial, 1960<br />

Brooks Memorial Art Gallery, Memphis, Tennessee, Art<br />

Today, 1960<br />

Silvermine Annual Exhibitions, New Canaan, Connecticut,<br />

1960s<br />

14

Brooklyn Museum, New York, International Watercolor<br />

Biennial, 1961<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Geometric<br />

<strong>Abstract</strong>ion in America, 1961<br />

Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Art of Assemblage,<br />

1961 (traveling exhibition)<br />

American Federation of Arts, Provincetown: A Painter’s Place,<br />

1962<br />

American Federation of Arts, Lyricism in <strong>Abstract</strong> Art, 1962<br />

Mt. Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts, Women<br />

Artists in America Today, 1962<br />

Museum of Modern Art, New York, Hans Hofmann and his<br />

Students, 1963 (traveling exhibition)<br />

Newark Museum, New Jersey, Women Artists in America,<br />

1707–1964, 1965<br />

Long Island University, Southampton, New York, 1965<br />

University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley,<br />

Selection 1967: Recent Acquisitions in Modern Art, 1967<br />

Washburn Gallery, New York, Museum of Non-Objective<br />

Painting, 1972<br />

State University of New York at Binghamton,<br />

8 Contemporary American Artists, 1973<br />

American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York,<br />

Recipients of Honors Exhibition, 1974<br />

Pratt Institute, New York, Recent <strong>Abstract</strong> Paintings, 1974<br />

Freedman Art Gallery, Albright College, Reading,<br />

Pennsylvania, Perspective, 1977<br />

Heckscher Museum, Huntington, New York, Artists of<br />

SuVolk County, 1978<br />

Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York, Women<br />

Artists of Eastern Long Island, 1979<br />

Ashawagh Hall, East Hampton, New York, The Springs<br />

Artists Exhibition, 1979<br />

Cultural Center, Paris, 15 <strong>Abstract</strong> Expressionists, 1979<br />

Phoenix Gallery, Gallery I, Maryland, Artists of East<br />

Hampton, 1979<br />

Marilyn Pearl Gallery, New York, Geometric Tradition in<br />

American Painting: 1920–1980, 1980<br />

Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York, 17 <strong>Abstract</strong><br />

Artists of East Hampton: The Pollock Years 1946–56, 1980<br />

Summit Art Center, New Jersey, American Artists: The Early<br />

Years, 1981<br />

Phoenix Gallery, Gallery II, Washington, D.C., Drawings,<br />

1981<br />

Mabel Smith Douglas Library, Rutgers University, New<br />

Brunswick, New Jersey, Modern Masters: Woman of the<br />

First Generation, 1982<br />

Ingber Gallery, New York, The Return of <strong>Abstract</strong>ion, 1984<br />

Elaine Benson Gallery, Bridgehampton, New York,<br />

Some Major Artists of the Hamptons, Then and Now:<br />

1960s–1980s, 1984<br />

Ingber Gallery, New York, A Colorful Retrospective: Works<br />

on Paper, 1986<br />

Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York, East<br />

Hampton Avant-Garde: A Salute to the Signa Gallery, 1990<br />

Baruch College Gallery, City University of New York,<br />

Reclaiming Artists of the New York School: Toward a More<br />

Inclusive View of the 1950s, 1994<br />

Baruch College Gallery, City University of New York,<br />

Women and <strong>Abstract</strong> Expressionism: Painting and Sculpture,<br />

1945–1959, 1994<br />

Provincetown Art Association and Museum, Massachusetts,<br />

New York—Provincetown: A 50’s Connection, 1994<br />

Thomas McCormick Gallery, Chicago, <strong>Abstract</strong><br />

Expressionism: Second to None, 2001<br />

Thomas McCormick Gallery, Chicago, <strong>Abstract</strong><br />

Expressionism: Second to None, Revised and Expanded, 2004<br />

Rockford Art Museum, Illinois, Reuniting an Era—<strong>Abstract</strong><br />

Expressionists of the 1950s, 2005<br />

Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, Paper Works by <strong>Abstract</strong><br />

Masters, 2006<br />

Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, Suitcase Paintings: Small<br />

Scale <strong>Abstract</strong> Expressionism, 2007 (traveling exhibition)<br />

Museo d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona and<br />

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina SoWa, Spain,<br />

Be-Bomb: The Transatlantic War of Images and all that<br />

Jazz, 1946–1956, 2007<br />

15

16<br />

Cool Series, No. 35, Shape-Up ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 70 x 80 in.

Cool Series, No. 29, Cool Blue Cold Green ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 60 x 70 in.<br />

17

18<br />

Cool Series, No. 2, (Yellow over Tan) ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 60 x 50 in.

Cool Series, No. 1, (Red over White) ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 60 x 50 in.<br />

19

20<br />

Cool Series, No. 26, FirST Love ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 47 x 59 in.

Cool Series, No. 36, Rough-Hewn ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 68 x 84 in.<br />

21

Cool Series, (Blue over Red) ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 40 x 36 in.<br />

(COver illustration)<br />

22

Cool Series, No. 15, The Very End ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 84 x 68 in.<br />

23

24<br />

Cool Series, (red over Yellow) ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 22 x 24 in.

Cool Series, No. 44, Double-Square ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 50 x 60 in.<br />

25

26<br />

Cool Series, No. 34, Ensign ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 68 x 84 in.

Cool Series, No. 7, Square Shooter ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 39 1 ⁄2 x 39 1 ⁄2 in.<br />

27

28<br />

Cool Series, No. 80, Impatient Spring ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 84 x 68 in.

Cool Series, No. 22, Wide U ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 50 x 60 in.<br />

29

30<br />

Cool Series, No. 9, Gibraltar ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 68 x 84 in.

Cool Series, (Orange over Yellow)<br />

ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 14 x 16 in.<br />

Cool Series, (Plum over pink)<br />

ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 12 x 12 in.<br />

31

32<br />

Cool Series, No. 46, Spanking Fresh ca. 1961–1963 Oil on canvas 50 x 60 in.

<strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> in her studio, New York City, 1962.<br />

Back cover: <strong>Perle</strong> <strong>Fine</strong> in her studio, Springs, New York, 1962.

SPANIERMAN MODERN<br />

53 EAST 58TH STREET new york, ny 10022-1617 SPANIERMANMODERN.com