Learning from Basque ancient pollards - Forestry Journal

Learning from Basque ancient pollards - Forestry Journal

Learning from Basque ancient pollards - Forestry Journal

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Over the last five years Helen Read, <strong>from</strong> the City of London, has been<br />

building relationships with tree workers in the <strong>Basque</strong> Country following<br />

a Europe wide study tour. In this article she explains how we can learn<br />

<strong>from</strong> the traditional techniques still practiced in Spain and looks at the<br />

sustainable management of their pollard trees.<br />

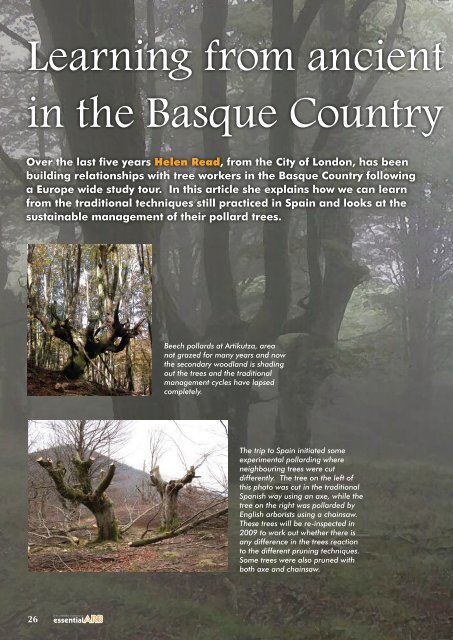

Beech <strong>pollards</strong> at Artikutza, area<br />

not grazed for many years and now<br />

the secondary woodland is shading<br />

out the trees and the traditional<br />

management cycles have lapsed<br />

completely.<br />

The trip to Spain initiated some<br />

experimental pollarding where<br />

neighbouring trees were cut<br />

differently. The tree on the left of<br />

this photo was cut in the traditional<br />

Spanish way using an axe, while the<br />

tree on the right was pollarded by<br />

English arborists using a chainsaw.<br />

These trees will be re-inspected in<br />

2009 to work out whether there is<br />

any difference in the trees reaction<br />

to the different pruning techniques.<br />

Some trees were also pruned with<br />

both axe and chainsaw.<br />

26<br />

1

The art of restoring lapsed <strong>pollards</strong><br />

is a new one, necessitated by many<br />

decades or even centuries since<br />

the trees were last ‘working trees’<br />

that were cut for their wood. Sadly<br />

this long lapse, for beech trees in<br />

particular, has meant that we cannot<br />

find people in Britain who pollarded<br />

trees for a living and there is little<br />

information about how to start new<br />

<strong>pollards</strong> or how they were managed<br />

in a regular cutting cycle.<br />

In 2003 I undertook a study tour<br />

across northern Europe in order<br />

to try and find out more about<br />

the technique of pollarding and<br />

especially to try and discover more<br />

about beech <strong>pollards</strong>. The last area<br />

I visited was the <strong>Basque</strong> Country,<br />

which straddles the south west of<br />

France and northern Spain, and this<br />

proved to be the most interesting<br />

and relevant. I was also fortunate to<br />

meet people who have subsequently<br />

become good friends and who<br />

have enabled us to discover more<br />

about their culture and past tree<br />

management practices.<br />

In the <strong>Basque</strong> Country there are<br />

tremendous numbers of beech<br />

<strong>pollards</strong>. In some communities they<br />

were located on common pastures<br />

belonging to the village or town and<br />

were essential for domestic fuel. In<br />

other places, close to the coasts,<br />

there were extensive areas of land<br />

with pollarded trees, the wood <strong>from</strong><br />

27

Feature: <strong>Learning</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>ancient</strong> <strong>pollards</strong> in the <strong>Basque</strong> Country<br />

Feature: Article Title<br />

These beech <strong>pollards</strong> at Oieleku<br />

were cut in the past to make<br />

charcoal for use in iron foundries.<br />

Today the land underneath is still<br />

grazed by sheep and ponies.<br />

Pollard cut at Leitza to a charcoal<br />

makers specification in Feb 2007,<br />

with the photograph taken in June<br />

2008.<br />

which was converted to charcoal<br />

and then used to fuel iron smelting<br />

works. Many other special trees also<br />

co-existed with the ‘traditional’ type<br />

of <strong>pollards</strong>. These were trees cut and<br />

shaped for particular pieces of wood,<br />

such as curves and forks, for use in<br />

ship building. The iron and wood<br />

were essential raw materials for the<br />

economically important <strong>Basque</strong> ship<br />

building industry along the coast.<br />

In contrast to the beech trees at<br />

Burnham Beeches, last cut for their<br />

wood around 200 years ago, some<br />

of these <strong>Basque</strong> trees have barely<br />

lapsed. There are also elderly people<br />

who were charcoal makers in their<br />

youth and are still very much alive<br />

and able to describe how the tree<br />

cutting was carried out.<br />

Since my initial visit there has been a<br />

great deal of exchange between the<br />

<strong>Basque</strong>s and various different ‘tree<br />

people’ <strong>from</strong> Britain. Members of the<br />

Ancient Tree Forum in particular have<br />

explored the area and found much<br />

of interest, not only regarding beech<br />

<strong>pollards</strong> but some huge and <strong>ancient</strong><br />

oak trees, ash <strong>pollards</strong> cut for fodder<br />

and some landscapes rich in veteran<br />

trees.<br />

28<br />

A key feature of all the visits has<br />

been the opportunity to talk to<br />

local people, nature conservation<br />

professionals, arboriculturalists<br />

and historians. The benefit of<br />

this has been to raise awareness<br />

of the value of these trees and to<br />

promote appropriate management.<br />

Pollarded trees are so common in<br />

the landscape that most people were<br />

unaware of their importance and<br />

value and therefore did not realise<br />

the European significance of what<br />

they have on their door step.<br />

Coupled with these site based visits,<br />

Ted Green, Neville Fay and myself<br />

have led workshops and given<br />

presentations on the value and<br />

management of <strong>ancient</strong> trees and<br />

many of these have been directly<br />

to arboriculturalists. We have built<br />

good relationships with Trepalariak<br />

– the <strong>Basque</strong> Arboricultural<br />

Association— and have worked<br />

closely with several of their members.<br />

In the summer of 2006 a couple<br />

of <strong>Basque</strong>s came to England and<br />

worked for a few days at Epping<br />

Forest and Burnham Beeches.<br />

Pollards in the <strong>Basque</strong> Country were<br />

traditionally cut with axes and there<br />

is still a very strong axe culture there.<br />

We invited an axe worker so he could<br />

show us more about how he worked.<br />

During the visit we held an ‘open<br />

afternoon’ so that anyone who was<br />

interested could come and have a<br />

look.<br />

Then in February 2007 a group<br />

<strong>from</strong> the City of London, including<br />

five arboriculturalists, spent a week<br />

in the <strong>Basque</strong> Country. They took<br />

their chainsaws with them and<br />

participated in an experiment that<br />

was also intended to highlight the<br />

importance of these trees to local<br />

people. Working alongside <strong>Basque</strong><br />

arboriculturalists <strong>from</strong> Trepalariak<br />

and local people wielding axes, 40<br />

trees were cut in two main locations.<br />

In one area (Oieleku) the aim was to<br />

compare cutting to the specification<br />

of the charcoal makers with that<br />

of the more gradual restoration<br />

techniques we use in England (all<br />

trees being cut with chainsaws)<br />

and some 25km south in the other<br />

area (Leitza) the charcoal makers’<br />

specification was used but some trees<br />

were cut with axes and some with<br />

chainsaws (and a small number half<br />

and half). The traditional method of<br />

cutting requires that almost all the<br />

branches of the pollard are removed<br />

leaving generally quite short stubs.<br />

Small branches were retained but<br />

generally only very thin ones. This<br />

technique is not something we would<br />

3

Feature: <strong>Learning</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>ancient</strong> <strong>pollards</strong> in the <strong>Basque</strong> Country<br />

Trees at Leitza cut to the charcoal<br />

makers specification in Feb 2007,<br />

photograph taken at time of cutting.<br />

Tree cut with chainsaw<br />

One year after pollarding this tree<br />

had a few new shoots growing<br />

low down on the branches so it<br />

was scored with an axe to try and<br />

stimulate more growth<br />

consider attempting on old <strong>pollards</strong><br />

in Britain but a small number of trees<br />

cut like this in the years immediately<br />

prior to our work in the <strong>Basque</strong><br />

Country showed good initial growth.<br />

It is interesting that the charcoal<br />

makers were convinced that trees<br />

that we cut as a gentle reduction<br />

would die and most of the British<br />

were convinced that trees cut in the<br />

manner of the charcoal makers<br />

would die! The cutting cycle of<br />

<strong>pollards</strong> in the <strong>Basque</strong> Country seems<br />

to vary. In some places it is similar to<br />

that in Britain but in others a length<br />

of up to 50 years is reported. At least<br />

some of the trees that were worked<br />

on were last cut approximately 50<br />

years ago and so were barely out of<br />

cycle.<br />

In June 2008, midway through<br />

the second growing season after<br />

cutting, a small group of British<br />

people returned to the trees as part<br />

of a longer visit. The following<br />

comments are based on a quick<br />

visual assessment of the trees. At the<br />

location where the cutting with axes<br />

and chainsaws had been compared<br />

the trees all showed new growth,<br />

much of which was good and strong,<br />

and largely in the form of new shoots<br />

<strong>from</strong> the cut branches (something<br />

that is relatively rare in southern<br />

England). Some branches had not<br />

faired so well and there appeared<br />

to be a degree of variation between<br />

trees that did not seem to be related<br />

to the cutting tool used. In contrast,<br />

the trees in the more northerly area<br />

that had been cut hard, were not<br />

growing so well and those cut in a<br />

more gentle way appeared stronger<br />

and healthier. The difference in<br />

response may be related to location<br />

and climate or perhaps the age/<br />

condition of the trees at the time of<br />

cutting. It is planned to return in<br />

2009 to carry out a more detailed<br />

evaluation of the responses of the<br />

trees and hopefully this will be<br />

reported on when we return.<br />

The sheer numbers of pollarded<br />

beech trees in this area enables us to<br />

learn <strong>from</strong> actions and experiments<br />

that we would be unable or unwilling<br />

to undertake in Britain because of the<br />

vulnerability of our remaining tree<br />

populations. In exchange we hope<br />

that our experiences with <strong>ancient</strong><br />

trees have enabled the local people<br />

to view their trees in a different light<br />

and to learn about new techniques<br />

that they have not encountered<br />

previously.<br />

Lapsed Beech <strong>pollards</strong> in the mist<br />

Gorbeia Natural Park<br />

All pictures by Helen Read<br />

294