1xmL3tg

1xmL3tg

1xmL3tg

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Spirit<br />

OF AUSTRALIA<br />

next wave<br />

Australian Indigenous contemporary<br />

art is flourishing as a vital component<br />

of the world’s oldest living culture.<br />

WORDS SUSAN McCULLOCH<br />

IN THE WORLD of visual artist Tony Albert,<br />

hierarchies are precarious things. His metre-high triangular<br />

towers of vintage playing cards are delicately balanced affairs.<br />

Laced with fine metal and collaged images, symbols and<br />

loaded text (“We Come In Peace”, “Space Invaders”), they<br />

point to the role that chance plays in determining cultural<br />

identity. Other recent works show Indigenous young men as<br />

moving targets, skating across the canvas like warriors of<br />

yesterday, while others highlight the inherent racism of kitsch<br />

souvenirs from times past. Such images have won this<br />

33-year-old, North Queensland artist both the 2014 Basil<br />

Sellers Art Prize and the 2014 National Aboriginal and Torres<br />

Strait Islander Art Award.<br />

Daniel Boyd’s large mixed-media work, which won the<br />

Queensland Kudjila/Gangula painter this year’s $80,000<br />

Bulgari Award at the Art Gallery of NSW, is a poignant meld<br />

of the personal and the historic in its referencing of Vanuatu’s<br />

Pentecost Island, which was 31-year-old Boyd’s great, great<br />

grandfather’s country before he was brought to Australia as<br />

a “blackbird” slave worker for the sugarcane industry. ›<br />

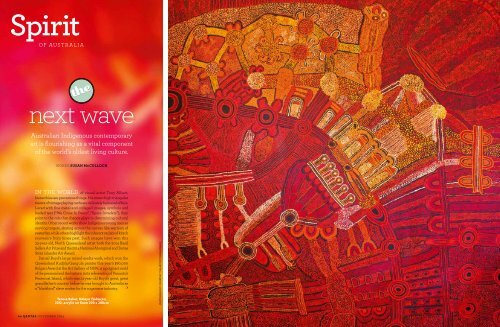

Teresa Baker, Kalaya Tjukurpa,<br />

2012, acrylic on linen 200 x 200cm<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY: COURTESY THE ARTIST/TJUNGU PALYA<br />

44 QANTAS NOVEMBER 2014

SPIRIT OF AUSTRALIA ART<br />

Tony Albert, We Come In Peace,<br />

2014, vintage playing cards and<br />

metal (left); Mavis Ngallametta,<br />

Kendall River, 2012 (below)<br />

MAVIS NGALLAMETTA: MARTIN BROWNE/COURTESY THE ARTIST/MARTIN BROWNE CONTEMPORARY, SYDNEY; TONY ALBERT: COURTESY GREG PIPER & SULLIVAN+STRUMPF FINE ART, SYDNEY<br />

Yhonnie Scarce, of Kokatha and Nukunu heritage (South<br />

Australia) explores the aesthetic power of glass in luminous sculptural<br />

installations that the 41-year-old calls “politically motivated<br />

and emotionally driven”. In the elegant, monochromatic prints of<br />

Queensland photo-artist Michael Cook, a 46-year-old Bidjara man,<br />

exist an alternative reality hovering between contemporary and<br />

colonial eras as the question is posed: “What if the British, instead<br />

of dismissing Indigenous societies, had taken a more open approach<br />

to their culture”<br />

ALBERT, BOYD, SCARCE and Cook are at the forefront<br />

of a growing school of new-generation, urban Indigenous artists,<br />

many art school-trained, whose work is being exhibited here and<br />

overseas, snapped up by institutions and private collectors, and<br />

recognised with awards. Their contemporaries include painters<br />

Christopher Pease, photographers Nici Cumpston, Archie Moore<br />

and Bindi Cole, installation artist Jonathan Jones, and multimedia<br />

artists Reko Rennie and Brian Robinson. Amsterdam-based photo,<br />

video and sound artist Christian Thompson is undertaking a PhD<br />

in Fine Art at Oxford University, one of the first two Indigenous<br />

Australian students at the 900-year-old centre of learning.<br />

Many of them don’t necessarily label themselves Indigenous, yet<br />

most identify strongly with their heritage and reference it in their<br />

art, along with that of a broader Indigenous experience. They follow<br />

a trail blazed by artists such as Tracey Moffatt, Brook Andrew, Danie<br />

Mellor, Leah King-Smith, Vernon Ah Kee, Gordon Hookey, Arone<br />

Meeks, Joanne Currie, Bianca Beetson, Destiny Deacon, Robert<br />

Campbell, Trevor Nickolls, Richard Bell, Gordon Bennett, Judy<br />

Watson, Lorraine Connelly Northey, Darren Siwes and Fiona Foley.<br />

These artists, in works of telling narrative or pithy commentary, have<br />

helped shape a new visual identity for Australia by placing the<br />

Indigenous experience at the cutting edge of contemporary art<br />

practice. Are these, then, the new faces of Australian Indigenous art<br />

Where do the canvases of the desert, the ochres of the Kimberley<br />

and barks of the Top End that have long dominated the popular face<br />

of Aboriginal art now fit<br />

“I believe there’s work of stature being produced in many areas of<br />

Indigenous art,” says National Gallery of Victoria director Tony<br />

Ellwood. “The work of artists such as Michael Cook, who was the<br />

talk of the Biennale of Sydney, Tony Albert, Yhonnie Scarce and<br />

other art school-trained artists are definitely attracting a huge<br />

amount of attention, but so, too, are many of the newer generation<br />

of artists of the APY Lands (Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara),<br />

Papunya, the Top End, Queensland, the Torres Strait Islands and<br />

other regions. It’s all adding up to a very rich scene.”<br />

The NGV’s own recent survey of Victorian contemporary art,<br />

Melbourne Now, featured the work of emerging Victorian Indigenous<br />

artists Steaphen Paton, Brian Martin and Maree Clarke, weaver and<br />

multimedia artist Lisa Waup, and photographer Steven Rhall. ><br />

NOVEMBER 2014 QANTAS 47

SECTIONHEAD LIGHT<br />

Daniel Boyd with his<br />

untitled 2014 Bulgari<br />

Art Award winning<br />

entry (above); Michael<br />

Cook, Civilised #5, 2012<br />

(above right); Michael<br />

Cook, Undiscovered #2,<br />

2010 (right)<br />

Ellwood’s view is shared by<br />

South Australian Indigenous<br />

art curator Nici Cumpston.<br />

“I think there’s an equal, if<br />

perhaps different, following<br />

for art from the urban areas<br />

than that from the more remote regions,” she says. Cumpston, of<br />

Afghan, English, Irish and Barkindji heritage, is an exhibiting art<br />

photographer and the director of Tarnanthi, an Indigenous visual<br />

arts festival to be held in Adelaide in October 2015. She has been<br />

proactive in building relationships with the painting communities<br />

of the APY and NPY (Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara)<br />

lands of northern and western South Australia. The first wave of<br />

artists from this region in the 1990s included the late master painters<br />

Jimmy Baker, Tiger Palpatja, Wingu Tingima, Eileen Stevens,<br />

Tommy Mitchell, Robin Kankakapatja, Militjari Pumani and the<br />

still-living Hector Burton, Jimmy Donegan, Tommy Watson and<br />

Dickie Minyintiri. Theirs was a late outpouring of desert art, bursting<br />

onto the scene more than 20 years after the Western Desert Papunya<br />

movement set the benchmark for desert painting with works<br />

collected at fever pitch for more than a decade.<br />

“Adelaide is fortunate to be placed historically as the<br />

administrative centre for much of these lands, giving<br />

us the opportunity to reinforce these links artistically,”<br />

says Cumpston. “However, such collaborative process<br />

must be entirely equal and grow over time, with full<br />

acceptance by not only the artists, but their broader<br />

communities.” Collaborative projects such as the large<br />

installation of birds in flight by the women of the Tjanpi<br />

Desert Weavers that featured in the Art Gallery of South<br />

Australia’s 2013 Heartland exhibition – and the multiartist<br />

paintings the gallery commissions – may be an<br />

end in themselves. However, notes Cumpston, the<br />

enthusiasm that such projects inspire often flows on to<br />

artists’ individual practice.<br />

The new wave of painters from this region include<br />

Tjungkara Ken, Sylvia Kanytjupai Ken, Nyumiti Burton,<br />

Tjungkaya Tapaya and Carlene Thompson; some, such<br />

as Linda Stevens, Teresa Baker and Betty Pumani are the daughters<br />

and grand-daughters of founding painters. The large-scale ceramics<br />

by Ernabella artists are also winning praise nationally.<br />

In the Top End, Darwin’s Museum & Art Gallery of the Northern<br />

Territory added a $5000 Youth Award to its range of prizes for this<br />

year’s National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Awards.<br />

Finalists included Amata, South Australian photographer and artist<br />

Rhonda Dick, Yirrkala’s Burrthi Marika, South Australia’s James<br />

Tyler and Year 12 Sydney student Harley Grundy, along with ><br />

DANIEL BOYD PHOTOGRAPHY: JENNI CARTER; MICHAEL COOK: COURTESY THE ARTIST/ANDREW BAKER ART DEALER, BRISBANE<br />

48 QANTAS NOVEMBER 2014

SECTIONHEAD LIGHT<br />

Kieren Karritypul, Yerrgi (detail), 2014 (above);<br />

Gunybi Ganambarr, natural earth pigments on<br />

larrakitj (sacred pole), 2013 (right)<br />

inaugural Youth Award winner Kieren Karritypul,<br />

who comes from from Daly River.<br />

In East Arnhem Land at Yirrkala the traditional<br />

medium of bark painting is also undergoing something<br />

of a revolution. Gnarled and pitted tree trunks,<br />

irregular shaped barks, glistening thin strips of metal, PVC piping,<br />

industrial-grade rubber offcuts from the conveyor belts of a nearby<br />

bauxite mine, ceiling insulation and galvanised iron from old water<br />

tanks – all these materials have provided Yirrkala artist Gunybi<br />

Ganambarr with a rich source of surfaces on which to create finely<br />

wrought, innovative and award-winning works of art.<br />

The 41-year-old Ganambarr started making art in the mid 2000s<br />

and within a few years had won major awards including Queensland<br />

Art Gallery’s Xstrata Coal Emerging Indigenous Artists Award in<br />

2008 and the 2011 WA Indigenous Art Award. “It started from [my<br />

learning of] our djalkiri (foundation) of our law. I saw what<br />

was true and what was false, I began to learn more and<br />

more. I worked on the same level, flat bark, and then it<br />

started to change and kept changing,” he says.<br />

Sydney critic John McDonald calls him “a revolutionary<br />

artist, more so than any artist I’ve known, including<br />

Picasso.” Will Stubbs, coordinator of Yirrkala’s Buku<br />

Larrnggay Mulka art centre calls Ganambarr an artist who<br />

plays by the rules of his clan, but “transgresses every<br />

stylistic boundary set by habit or convention... working<br />

within an age-old set of beliefs, he treats the secular<br />

elements of his art as a field of unlimited possibility.”<br />

Ganambarr, whose 12 years as a builder in East Arnhem<br />

Land communities also plays a pivotal role in his art, says<br />

that he uses reclaimed materials both for their creative<br />

potential and for environmental reasons – to “give the trees<br />

a rest” from over-culling for didgeridoo and art making,<br />

as well as “to balance the Yolngu [Arnhem Land people]<br />

and Ngapaki [European] world systems”.<br />

Like Ganambarr, mid-40s painter Yukultji Napangati’s<br />

first solo show (in Sydney this year) was a sell-out. One of<br />

the younger artists of the powerhouse desert art centre<br />

Papunya Tula, Napangati is part of the family who walked<br />

in to Kiwirrkura in 1984 to worldwide media claims as<br />

being among the last to have lived a fully traditional bush<br />

life. She starting painting in 1996, was selected for the<br />

Museum of Contemporary Art’s emerging artists survey,<br />

Primavera, in 2005, and was a Wynne Prize finalist in 2011<br />

and 2013. Her closely placed lines of dots track the surface<br />

of the canvas with such fluidity that they appear, as her<br />

Sydney gallery director Christopher Hodges says, “like a<br />

heat haze or mirage”.<br />

At Aurukun, on Cape York Peninsula, the large-scale<br />

ochre and mixed-media canvases of Mavis Ngallametta<br />

have created what Sally Butler, senior lecturer in art history<br />

at the University of Queensland, calls “possibly the<br />

quietest stampede in the Australian art market. Over the<br />

past three and a half years, nearly every major public and<br />

private art collection in Australia has acquired large-scale<br />

[Ngallametta] paintings”. Her expansive canvases, with<br />

their meandering tidal flows, mountains and ochre washes<br />

are, says Butler, like “interactive maps” that offer a “vivid and intense<br />

experience of place that spirals across macro and micro perspectives<br />

of her coastal wetland region”.<br />

The 70-year-old Ngallametta’s paintings are stylistically and<br />

culturally different from any other Aboriginal work. As such, they<br />

exemplify one of the great truisms of Aboriginal art. As veteran<br />

Papunya Tula manager Paul Sweeney says: “Everyone’s looking for<br />

the new young art stars, but often the next ‘star’ that emerges will be<br />

a mid-40s or older man or woman who’s been working away quietly<br />

for some time and whose art just starts to gel.” A<br />

KARRITYPUL PHOTOGRAPHY: COURTESY ANNANDALE GALLERIES; GANAMBARR: COURTESY MUSEUM & ART GALLERY OF THE NT<br />

50 QANTAS NOVEMBER 2014