Relative Pronouns in An Alphabet of Tales, a Fifteenth Century ...

Relative Pronouns in An Alphabet of Tales, a Fifteenth Century ...

Relative Pronouns in An Alphabet of Tales, a Fifteenth Century ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

31<br />

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong><br />

<strong>Century</strong> Northern Text<br />

Toshio<br />

Saito<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> English, Nara University <strong>of</strong> Education, Nara, Japan<br />

<strong>An</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> the relative constructions <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong> with special reference<br />

to relative pronouns is attempted <strong>in</strong> this paper as part <strong>of</strong> the present writer's survey<br />

<strong>of</strong> the relative constructions <strong>in</strong> 15th <strong>Century</strong> English. The study is <strong>in</strong>tended to present<br />

a general picture <strong>of</strong> how relatives are used <strong>in</strong> the Northern language <strong>of</strong> the late ME<br />

period. The work under <strong>in</strong>vestigation is a Northern English translation (c. 1450)1 <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Alphabet</strong>um Narrationum <strong>of</strong> Etienne de Basancon. The prose <strong>of</strong> the book reflects the<br />

colloquial language <strong>of</strong> the period though it is an English translation from the Lat<strong>in</strong>.2<br />

The text used <strong>in</strong> this survey is <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, pt. 1 edited by Mrs. Mary Macleod<br />

Banks (EETS, OS. 126, 1904).<br />

1. 0. FORMS<br />

In the present survey the passages <strong>of</strong> narrative exposition (abbr. NAR) and those <strong>of</strong><br />

discourse (abbr. DIS) are separately <strong>in</strong>vestigated s<strong>in</strong>ce it is naturally expected that there<br />

is some difference <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic levels between the two.<br />

<strong>Relative</strong> pronouns are classified <strong>in</strong>to two groups: (1) relatives with an antecedent,<br />

(2) relatives without an antecedent. The relatives <strong>of</strong> the latter group may be divided<br />

<strong>in</strong>to simple forms and compounds.<br />

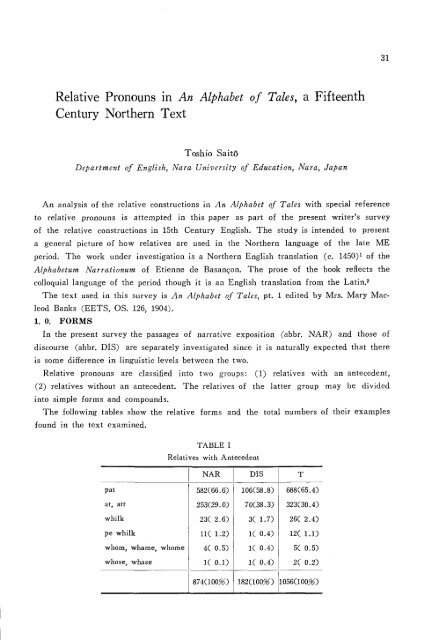

The follow<strong>in</strong>g tables show the relative forms and the total numbers <strong>of</strong> their examples<br />

found <strong>in</strong> the text exam<strong>in</strong>ed.<br />

TABLEI<br />

<strong>Relative</strong>s with <strong>An</strong>tecedent

32 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

TABLE<br />

II<br />

<strong>Relative</strong>s without <strong>An</strong>tecedent

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 33<br />

<strong>in</strong>g to my survey, the proportion between pat and wA-forms <strong>in</strong> MS Harley 7333 <strong>of</strong> Gesta<br />

Romanorum (c. 1440, Midland; abbr. GR)7 and The Book <strong>of</strong> Margery Kempe (c. 1430s,<br />

East Midland; abbr. MK)S is as follows:<br />

NAR<br />

GR 224 (61.5^) : 140(38.55^)<br />

MK 354 (47.7#) : 387(52.3^)<br />

DIS<br />

280 (74.996) å 94(25.<br />

299 (72.9&) : 98(27.<br />

As to another colloquial material, Paston Letters (1422-1509, East Midland;abbr. PL),<br />

when count<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> Carstensen's work9 are manipulated, we shall get the rate <strong>of</strong> approximately<br />

5&%: A7%. The statistics <strong>of</strong> these three works discloses that already <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Fifteenth</strong><br />

<strong>Century</strong> OT/z-forms, especially (pe) which, are rather highly developed even <strong>in</strong> colloquial<br />

prose, at least from the numerical po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view.10 Mustanojall states, "In later ME the<br />

dependent use <strong>of</strong> which becomes <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly popular and develops <strong>in</strong>to a mannerism at<br />

the hands <strong>of</strong> many 15th-century writers." In this respect <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong> is quite<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ct from these three works. The present writer is not sure if this leads to the conclusion<br />

that wh-iorms are scarce <strong>in</strong> the colloquial type <strong>of</strong> 15th <strong>Century</strong> Northern English.<br />

Further <strong>in</strong>vestigations have to be conducted on ther Northern texts.<br />

1. 1. The figures <strong>of</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g table <strong>in</strong>dicates the situation better.<br />

TABLEIII<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

r : restrictive relatives<br />

nr : non-restrictive relatives<br />

Restrictive wh- forms are negligible, be<strong>in</strong>g used <strong>in</strong> only 1.2^ <strong>of</strong> the cases, while with<br />

the non-restrictive clauses they have already ga<strong>in</strong>ed some ground, be<strong>in</strong>g used <strong>in</strong> 14.7%'<br />

<strong>of</strong> the cases. This is the sphere where anaphoric wh-iorms first came <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> early<br />

ME, and where they still l<strong>in</strong>ger <strong>in</strong> late ME.<br />

1. 2. There are 32 <strong>in</strong>stances <strong>of</strong> relatives re<strong>in</strong>forced with pleonastic conjunction pat or at.12<br />

Northern at appears also <strong>in</strong> this function.

34 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

TABLE<br />

IV<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>of</strong> significance <strong>in</strong> these figures are:<br />

<br />

(1) The comb<strong>in</strong>ation pat pat or pat at is not found.<br />

(2) Pleonastic pat is preferred <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with whilk and possibly with whom. At<br />

goes with what and zt>/za-compounds.<br />

(3) This comb<strong>in</strong>ation is used more frequently <strong>in</strong> NAR than <strong>in</strong> DIS. It may be worth<br />

not<strong>in</strong>g that 17 <strong>of</strong> all the 27 examples <strong>of</strong> whilk is followed by pat or at. In GR and MK<br />

the comb<strong>in</strong>ation with pleonatic pat is not so popular, and it appears less frequently <strong>in</strong><br />

NAR than <strong>in</strong> DIS.13<br />

i. (NAR) whilk pat per was a preste pat servid <strong>in</strong> a kurk <strong>of</strong> Saynt Agnes, whilk pat<br />

on a tyme was hugelie vexid with temptacion <strong>of</strong> his flessh 32-31/per was a wurthi<br />

knyght whilk pat did many enjuries vnto Lowisll3-26/ he made paim a law att pai<br />

kepe yit, whilk pat is callid Machomett law 165-20. whame pat he commandid to gar<br />

feche vnto hym on pat hight Joseph, pat was a lew, whome pat he had sene be reuelacion<br />

at sulde be a crysten man 74-20/ he suld be made rewler <strong>of</strong> paim, whame pat<br />

God shewid for be pe Holie Gaste 165-12. whatt som euer pat Whatt howr som euer<br />

pat a synner forthynkis his syn 58-4.<br />

(DIS) whilk pat I hafe a pale face for I had mynd <strong>of</strong> pe paynys <strong>of</strong> hell, whilk pat I<br />

mond hafe bod if I did penance for my syn 56-33. whome pat Other mens wurdis sail<br />

neuer noy a man, how pat evur pai say, whom pat his consciens fylis noght 45-19.<br />

ii. (NAR) whilk at and tolde hym my dissese, whilk at I durste not for shame tell att<br />

hame vnto Euagerus 92-7. pe whilk att ffor pat, he said, was most delicious, pe whilk<br />

att mans witt cuthe ymagyn <strong>of</strong>f trewthe <strong>in</strong> a mans saule 103-25. what at & what at<br />

God wolde hafe dene 165-18. what att evur he suld do what att evur hym plesid to<br />

byd hymdo 148-16. (DIS) what at evur what at evur I hafe sail be p<strong>in</strong>e 49-25.<br />

1. 3. It may be added here that we have found only7 cases where the 0-form <strong>in</strong>troduces<br />

what Jespersen calls 'contact-clause.' Subject-relation: 3 exx.; object-relation: 2 exx.;<br />

adverbial: 2 exx. They are all found <strong>in</strong> NAR.<br />

i. per was a lew /0/ wonnyd <strong>in</strong> pe town 143-23/ his Abbot...was war <strong>of</strong> a lytle blak<br />

boy /0/ led hym onte be pe shurte <strong>of</strong> his clothis 79-25/ 10-25.<br />

ii. and wolde not lefe for noght/0/ sho cuth do 26-10/ pai wold bete hym for pe skorn

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 35<br />

10/ he gaff permaister 141-6.<br />

iii. I sail no meate eate vnto tyme /0/ I know if ourLord will hafe mercie <strong>of</strong> pe or<br />

noght 48-7.<br />

This scarcity <strong>of</strong> examples with 0-forms is not due to the fact that this is a translation<br />

from the Lat<strong>in</strong>, but probably it only reflects the late development <strong>of</strong> this construction <strong>in</strong><br />

English.14 This is not popular <strong>in</strong> GR and MK either.15<br />

2. 0. Whilk ; pe whilk<br />

Whilk (

36 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

113-26/ per was a husband-man whilk pat vsid, & all his howse-meneya, gretelie to<br />

herbar pure folk 251-12. rnpS with pat pai wer streken with a lepre whilk held paim<br />

vnto per lyvis end, & made ane end <strong>of</strong> paim 83-17. nrpS per was a holie Saynt pat<br />

hight Maria de Og<strong>in</strong>iez, whilk pat <strong>of</strong>t sithes punysshid hur selfe with grete abst<strong>in</strong>ence<br />

17-ll/<strong>An</strong>d pe iij frend is almighti God, whilk patt putt both His life & His sawle<br />

for His frendis 43-ll/ 2-ll/ 3-4/ 7-3/ 15-6/ 17-ll/30-19/ 32-31/ 38-5/ 71-6. nrpO per<br />

was a man pat had a son <strong>of</strong> xv yere age, whilk pat he luffyd passandlie wele, &<br />

broght hym vp tenderlie 82-9. nrpR when he saw pies ij men, <strong>of</strong> whilk pe tone sulde<br />

be sent furth pis message, he consydured at 72-7. nrpA per was a passand Cfavr maydyn)<br />

pat hight Thaysis, whilk maydyn hur modir <strong>in</strong> all hur yong age lete (6l6~} accordand<br />

to hur will 2-31/. per was a man boun <strong>in</strong> a howse pat had a fend <strong>in</strong> hym, whilk<br />

fend cawsid pis to vpbrayd ilkone at come <strong>in</strong> 123-16/ 2-ll/ nrnpS ye sail ynderstond<br />

pat pis ffurst frend is we[V]ldly possessions, whilk pat when we dye giffis vs bod a<br />

wyndyng clothe to lap vs <strong>in</strong> 43-8/ and come ad Montem Gaudii, whilk pat is bod halfe<br />

a lewke fro Saynt Iamys 256-28/ 165-20. nrnpO and tolde hym my dissese, whilk at<br />

I durste not for shame tell att hame vnto Euagerus 92-7. nrnpA <strong>in</strong> pe bowndis <strong>of</strong><br />

Cleopilas, <strong>of</strong> whilk region Pytaphar pe preste was pr<strong>in</strong>ce 61-23.<br />

(DIS) rnpR whare pou gat so gude spicis purgh whilk all our chawmer is fyllid so<br />

. full <strong>of</strong> gude savir with 117-31. nrnpO I hafe a pale face forI had mynd <strong>of</strong> pe paynys<br />

<strong>of</strong> hell whilk patI mond haf bod if I did penance for myn syn56-33/ I sail gif pe for<br />

my rawnson iij wisdoms, whilk & pou kepe, sail be grete pr<strong>of</strong>ett vnto pe 132-12. N.B.<br />

This whilk functions as the object <strong>of</strong> the adverbial clause. It is an <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>of</strong> relative<br />

concatenation.<br />

ii. pe Whilk (NAR) rnpR yit he said he forgatt a thyng, withoute pe whilk all oper<br />

p<strong>in</strong>ges may nott pr<strong>of</strong>ett 145-ll/ he had a certan vyneyard <strong>of</strong> pe whilk he had yereiie x<br />

ton <strong>of</strong> wyne 168-20. nrpR per he saw ij grete men, <strong>of</strong>pe whilk pe tane was an Erie,<br />

and pe toder a grete prelatt 151-29/ and pai wer hyelie accusid be for our Lord. Agayns<br />

pe whilk, purf all hym semyd passand grevid,..., he putt ourhis sentans 151-30/ 214-31.<br />

nrnpO ffor pat, he said, was most delicious, pe whilk att mans witt cuthe ymagyn <strong>of</strong>f<br />

trewthe <strong>in</strong> a mans saule 103-25. nrnpR <strong>An</strong>d aboute pis towre was per ane entre with a<br />

hy wall, with-<strong>in</strong> pe whilk per was fayre treis & frutefull <strong>of</strong> dyvers kyndis 62-18/ <strong>An</strong>d<br />

pis 'bisshop with grete devocion reseyvid it, purgh vertue <strong>of</strong> pe whilk he come agayn<br />

vnto his right mynde 113-5/ 52-20/ 62/5. nrnpA Be pe whilk p<strong>in</strong>g it is for to trow<br />

what meknes (DIS) rnpR I conjure pe & chargis the purgh pat charite be pe whilk<br />

laste day I ete fless for my monke sake, at pou tarie here no langer ll-4.<br />

A study <strong>of</strong> the figures <strong>of</strong> Table V and examples above reveals the follow<strong>in</strong>g facts:<br />

(1) Whilk and pe whilk are by far more non-restrictive than restrictive <strong>in</strong> the material<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ed.19 A further prob<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to the examples tells us that there are few <strong>in</strong>stances<br />

where whilk <strong>in</strong>troduces a cont<strong>in</strong>uative clause, while pe whilk is cont<strong>in</strong>uative <strong>in</strong> all the<br />

examples but one.

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 37<br />

(2) Both <strong>of</strong> them can be used as personal as well as non-personal relatives. There seems<br />

to be a slight tendency that while whilk is more personal than non-personal, pe whilk has<br />

stronger non-personal character.20<br />

(3) Whilk is mostly used <strong>in</strong> subject function. On the other hand pe whilk functions as<br />

a regimen<strong>of</strong> a preposition <strong>in</strong> all the cases exept one.<br />

These facts taken <strong>in</strong>to consideration, it may be concluded that there is a functional<br />

differentiation between these two forms at least <strong>in</strong> this Northern text: pe whilk is ma<strong>in</strong>ly<br />

used as a regimen <strong>of</strong> a preposition <strong>in</strong> a cont<strong>in</strong>uative relative clause, whereas whilk appears<br />

<strong>in</strong> other functions than that. Furthermore, pe whilk is rarely followed by a pleonastic<br />

conjunction pat or at, though whilk seems to be normally re<strong>in</strong>forced by pat or at.21<br />

A further scrut<strong>in</strong>y reveals an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g fact. When a relative modifies an antecedent<br />

which already has a relative clause or clauses, pe whilk is never used <strong>in</strong> the text, with 10<br />

examples where whilk appears. In this case the comb<strong>in</strong>ation whilk pat is always used<br />

except when whilk is attributive. This gives evidence that whilk pat has more carry<strong>in</strong>g<br />

force than pla<strong>in</strong> whilk.<br />

pat...whilk pat We rede <strong>of</strong> a monk pat hight Hubertus, whilk pat when he shulde<br />

dy, he askid straytJie pat pe abbott myght com vnto hym 15-6/ per was a knyght pat<br />

was <strong>in</strong> purgatorie, whilk pat was a gude man & luffid wele for to herber pure folk 71-<br />

6/ 2-ll/ 3-4/ 17-ll/ 38-5/ 32-31.<br />

pat...whilk per was a passand [7ayr mayden^] pat hight Thaysis, whilk maydyn hur<br />

modir <strong>in</strong> all hur yong age lete C^o^J accord<strong>in</strong>g to hur will 2-31.<br />

pat...whilk pat...whilk hym happend to mete with ane Abbott pat hight AppolJ<strong>in</strong>us,<br />

whilk pat knew pe cauce <strong>of</strong> his gate oute <strong>of</strong> his ordur, whilk abbott comfurtid hym<br />

with fayr wurdis 2-ll.<br />

At...whilk pat he made a law att pai kepe yit, whilk pat is callid Machomett law<br />

165-20.<br />

3. 0. Who; Whom; Whose<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

The follow<strong>in</strong>g examples are all that are found <strong>in</strong> the present text.<br />

a) <strong>Relative</strong>s with antecedent: Whame (NAR) rpO pat he shulde chese paim one <strong>of</strong><br />

ij, whame pai namyd 200-5. rpR he suld be made rewler <strong>of</strong> paim, whame pat God

38 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

shewid for be pe Holie Gaste 165-12. nrpO he commandid to gar feche vnto hym on<br />

pat hight Joseph, pat was a lew, whome pat he had sene be reuelacion at sulde be a<br />

crysten man 74-20. nrpR War vji maydyns pat servid pis Assenech, with whame spak<br />

nowder childe nor man 62-12. (DIS) nrpO Other mens wurdis sail neuer noy a man,<br />

how pat evur pai say, whom pat his consciens fylis noght. 45-19.<br />

Whose (NAR) rp per was a mayden whase name was Alexandria 14-19. (DIS) nrp pis<br />

my trew felow vuchesafe to hele <strong>of</strong> his lepre, for whose luffI was not ferd to shed my<br />

childre blude 40-20.<br />

b) relatives without antecedent: Who (NAR) & he had as who say nothyng to sell<br />

108-8. Who som-evur (NAR) who som-evur had it shulde bryng it agayn 232-9.<br />

This scarcity <strong>of</strong> who-iorms <strong>in</strong>dicates the more retarded development <strong>of</strong> them than that<br />

<strong>of</strong> which <strong>in</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> English. No examples <strong>of</strong> anaphoric who are found <strong>in</strong> the text.<br />

It is also the case with MK and GR. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Carstensen,22 sporadic occurrences <strong>of</strong><br />

who <strong>in</strong> this function are perceived <strong>in</strong> PL. Ryden states, "Who did not come <strong>in</strong>to common<br />

use as an anaphoric relative until the 16th century. In 15th century English it is rare<br />

except <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> stereotyped epistelary phrases."23 As to as who say <strong>in</strong> the above example,<br />

Visser says it was frequently used <strong>in</strong> Middle English.24<br />

It is impossible to say anyth<strong>in</strong>g about the functions <strong>of</strong> these forms <strong>in</strong> question on these<br />

scanty examples, but Mustanoja says, "There seems to be some tendency to use who<br />

(whose, whom) <strong>in</strong> non-def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g rather than def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g relative clauses."25 His statement<br />

applies to the examples found <strong>in</strong> MK and GR.26<br />

4.0. What<br />

ll <strong>in</strong>stances with what are found <strong>in</strong> the text. What as a relative which has the value<br />

<strong>of</strong> that which occurs 7 times <strong>in</strong> all (5 <strong>in</strong> NAR and2<strong>in</strong> DIS). The rest are the examples<br />

<strong>of</strong> relative adjectives. What takes at, not pat when it is re<strong>in</strong>forced with a pleonastic<br />

conjunction. See §1.2.<br />

What (NAR) & bad hym do with hym what he wolde 37-16/ pis yong felow at<br />

bere pis crippill hard what he said 231-14. (DIS) pou harde nott whatt I commawndid<br />

pe 5-6/ ye sail nott witt what I say 140-17.<br />

What at (NAR) he told paim all what at he saw 86-21/ & what at he mott safe<br />

over his meatt & his clothe, he wold go... & gi ff it vnto pure men 202-12/ 165-18.<br />

The first example <strong>of</strong> what at is <strong>in</strong>terpreted by Mustanoja27 as a case <strong>in</strong> which what is<br />

anaphoric.<br />

As to the scanty occurrence <strong>of</strong> what, ,we are referred to Partridge's statement, "The<br />

neuter relative what without antecedent is found as early as the 13th C, but did not come<br />

<strong>in</strong>to regular use until the 17th C."28<br />

In treat<strong>in</strong>g what (=that which), other parallel expressions such as pat and at are also<br />

to be taken <strong>in</strong>to consideration. Table VII confirms Partridge's remark. At and pat at are<br />

more frequent than what.<br />

pat (NAR) a man pat is shamefull vnpr<strong>of</strong>itable sulde titter fynde pat he desyrid,

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 39<br />

pan pat p<strong>in</strong>g att askid 37-29. Note the contrast between pat and pat p<strong>in</strong>g att. /sho<br />

sulde do vnto hym pat sho did neuer vnto no noder. 251-5.<br />

At (NAR) he myght grawnt hur at sho askid 75-27/ he began to forthynk at he<br />

had said 139-3/ 65-24/ 103-18/ 158-27/ 159-18/ 184-2/ 191-12/ 246-12/ 252-18. (DIS)<br />

Gyff me at I ask the 28-7/ Almi3tti God reward pe at pou hase done for me<br />

58-32/ 36-18/ 41-8/ 153-8/ 194-18/ 244-1.<br />

pat pat (NAR) how pat was taken fro hurpat God had giffen sho told hym 113-19.<br />

pat at (NAR) sho was <strong>in</strong>nocent <strong>of</strong> pat at sho was accusid <strong>of</strong> 12-19/ noman myght<br />

speke fayrer pat at he wold speke pan he bid 218-16/ 29-28/ 69-19/ 98-21/ 141-9/<br />

218-10/ 218-16/ 224-20. (DIS) wo isme for pat at sail happyn 118-17/ 168-23/ 65-16/<br />

80-9/ 89-ll/ 164-28.<br />

It at (NAR) he said he was redie to pr<strong>of</strong>e it at he had told hym 154-12.<br />

pat p<strong>in</strong>g pat (NAR) make not sorow for pat p<strong>in</strong>g pat is verely loste 132-17.<br />

(DIS) pu desyris me for to do for pe pat p<strong>in</strong>g pat is vnhoneste 41-10/ 132-29.<br />

pat p<strong>in</strong>g- pat (NAR) sho bad hym neuer to desyre to gett pat p<strong>in</strong>g at he myght<br />

not gett 132-16/ 37-29/ 85-27. (DIS) when I se pat p<strong>in</strong>g at I desire 17-29/ 132-30.<br />

TABLE VII<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

5. 0. pat; At<br />

In this section an attempt is made to f<strong>in</strong>d if there is any differentiation <strong>in</strong> function<br />

between these most common relatives <strong>in</strong> this Northern text. In Early ME pe and pat were<br />

current as relatives, and <strong>An</strong>gus Mclntosh successfully clarified the functional dist<strong>in</strong>ction<br />

between the two forms <strong>in</strong> the Midland dialects.29 A cursory glance <strong>of</strong> the examples <strong>of</strong><br />

pat and at collected for this survey does not give the present writer any hope to f<strong>in</strong>d<br />

such a clear-cut functional difference between them. The difference might be only that <strong>of</strong><br />

statistical frequency. Nevertheless, it would be worth try<strong>in</strong>g because there has been no<br />

work deal<strong>in</strong>g with this Northern form at as far as I know.<br />

5. 1. In the present text pat occurs 690 times <strong>in</strong> all (NAR 584: DIS 106), and at occurs<br />

340 times (NAR 263: DIS77). Therefore, pat is about twice as frequent as at. But the<br />

above figures <strong>in</strong>dicate that the ratio <strong>of</strong> pat to at is different <strong>in</strong> the two different categories<br />

<strong>of</strong> passages. The proportion between them is 68.8 : 31.2 <strong>in</strong> NAR anb 57.9 : 42.1 <strong>in</strong> DIS.

40 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

This fact that at is more frequent <strong>in</strong> DIS than <strong>in</strong> NAR may be <strong>in</strong>terpreted to show its<br />

colloquial and <strong>in</strong>formal character. OED may be quoted aga<strong>in</strong> as say<strong>in</strong>g it is a worn-out form <strong>of</strong><br />

pat. Is it too much to assume that there is some difference <strong>in</strong> speech level between pat<br />

and at just as there is between who/which and that <strong>in</strong> present-day English To confirm or<br />

discard this assumption, an exam<strong>in</strong>ationhas to be made on more literary prose than this text.<br />

5. 2. When the examples <strong>of</strong> relatives with antecedent are classified accord<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

personal/nonpersonal, restrictive/non-restrictive and subject/object/adverbial relations, we get<br />

the follow<strong>in</strong>g table.<br />

TABLE VIII<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Ad : adverbial O <strong>in</strong>cludes objects <strong>of</strong> verbs and regimens <strong>of</strong> prepositions.<br />

As a relative without antecedent pat occurs 2 times <strong>in</strong> NAR only, and at does 10 times<br />

<strong>in</strong>NAR and 7 times <strong>in</strong>DIS as is shown <strong>in</strong> Table II. In this function at is the norm.<br />

See§4.0.<br />

5. 3. Restrictive & Non-restrictive Table VIII shows the follow<strong>in</strong>g figures <strong>in</strong> terms<br />

<strong>of</strong> restrictive/non-restrictive function.<br />

NAR<br />

DIS<br />

pat r 480: nr 102 r 78: nr 28<br />

at r 200: nr 53 r 50: nr 20<br />

These figures do not tell us that there is any dist<strong>in</strong>ction <strong>in</strong> this function between the two.<br />

They both function non-restrictively as well as restrictively. Cont<strong>in</strong>uative relative clauses<br />

are quite rare, that is to say negligible <strong>in</strong> both pat and at. With this respect compare<br />

these forms with whilk and pe whilk.<br />

5. 4. Personal & Non-personal From Table VIII we get the follow<strong>in</strong>g statistics concern<strong>in</strong>g<br />

personal and non-personal uses <strong>of</strong> pat and at.<br />

NAR<br />

DIS<br />

pat p456:np126 p64:np~~42<br />

at 122: 131 26: 44<br />

578 257 90 86

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 41<br />

Po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>of</strong> significance <strong>in</strong> these figures are:<br />

a) In NAR personal relatives are over two times as frequent as non-personal ones,<br />

whereas <strong>in</strong> DIS both types <strong>of</strong> relatives are almost equally frequent.<br />

b) With the personal antecedent pat is def<strong>in</strong>itely preferred to at <strong>in</strong> both NAR and<br />

DIS. In refer<strong>in</strong>g to the non-personal antecedent both pat and at are used with almost<br />

equal frequency.<br />

c) The ratio <strong>of</strong> personal to non-personal pat is 78.4: 21.6 <strong>in</strong> NAR and 60.4:39.6 <strong>in</strong> DIS.<br />

At shows the proportion <strong>of</strong> 48.2 to 51.8 <strong>in</strong> NAR and that <strong>of</strong> 37.1 to 62.9 <strong>in</strong> DIS.<br />

b) and c) considered, it may be said that pat has more personal character, -while with<br />

respect to at the non-personal force is stronger though it is frequently used <strong>in</strong> both functions.<br />

5. 5. Case Relation The follow<strong>in</strong>g tabulation is obta<strong>in</strong>ed from Table VIII when the<br />

<strong>in</strong>stances with pat and at are considered <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> subject/object function:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

From these figures <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts emerge:<br />

a) As a whole subject-function is far more frequent than object-function <strong>in</strong> this text.<br />

b) With personal relatives subject-function predom<strong>in</strong>ates.30 In both NAR and DIS pat<br />

is used with greater frequency to perform this function.<br />

c) With respect to non-personal relatives, on the other hand, object-function occurs more<br />

frequently,30 and it is performed by at with predom<strong>in</strong>ance.<br />

The conclusion <strong>in</strong> the preced<strong>in</strong>g section is positively endorsed by the figures <strong>in</strong> this<br />

table. It may roughly be said that the ma<strong>in</strong> job <strong>of</strong> pat is to perform the subject-function<br />

as a personal relative while that <strong>of</strong> at is <strong>in</strong> the non-personal/object-function.<br />

5. 5. Types <strong>of</strong> <strong>An</strong>tecedents Types <strong>of</strong> antecedents are to be exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> order to make<br />

a further scrut<strong>in</strong>y <strong>of</strong> pat and at. The antecedents may be classified roughly <strong>in</strong>to three<br />

groups:nouns, pronouns, and clauses (or phrases). The follow<strong>in</strong>g are the statistics for the<br />

distribution <strong>of</strong> pat and at <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> antecedent types. Only 4 <strong>in</strong>stances are found <strong>in</strong><br />

which a relative refers to a clause. Two <strong>of</strong> them are the cases with relatives <strong>in</strong> frontposition31<br />

which have alreadybeen given <strong>in</strong> §1. 0. Note 3. The other two are the follow<strong>in</strong>g:

42 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

(NAR) pe devull sett fire per<strong>in</strong> & burnyd it vp & destroyed itt euere dele, pat all folke<br />

mott se 199-8/ a syluer pece wasput <strong>in</strong> his skripp privalie, at he wiste not <strong>of</strong>f 257-9.<br />

TABLEX<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

N : noun antecedent P : pronoun antecedent C : clause antecedent<br />

As may be expected, noun antecedents are far more frequent than the other two, the<br />

percentages <strong>of</strong> N, P and C be<strong>in</strong>g 77.3:22.3:0.4 <strong>in</strong> NAR and 65.6:34.4:0.0 <strong>in</strong> DIS.<br />

In the face <strong>of</strong> the figures <strong>of</strong> the table it is rather hard to detect any def<strong>in</strong>ite trend <strong>in</strong><br />

the use <strong>of</strong> pat and at accord<strong>in</strong>g to types <strong>of</strong> antecedents. Roughly speak<strong>in</strong>g, pat seems to<br />

have a tendency to accompany personal antecedents whether they are nouns or pronounrs.<br />

With regard to noun antecedents at tends to be non-personal, and with pronoun antecedents<br />

it is personal as well as non-personal.<br />

5. 6. Noun <strong>An</strong>tecedents The follow<strong>in</strong>g tabulation may be obta<strong>in</strong>ed when noun antecedents<br />

are grouped <strong>in</strong>to the patterns below:<br />

a) NAR<br />

TABLEXI

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 43

44 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

Notes: 1. "a+N" stands for "Indef<strong>in</strong>ite article+ (adjective) +Noun."<br />

2. "0+N" stands for "No article+(adjective) +noun."<br />

3. Gen: genitive case <strong>of</strong> (pro)noun Superl: superlative Num: numeral<br />

A study <strong>of</strong> the figures <strong>of</strong> these two tables will disclose very significant facts:<br />

1) Pat is def<strong>in</strong>itely preferred with antecedents with patterns a +N, 0-\-N and Num-\-<br />

N. It is to be noted that the majority <strong>of</strong> cases with pat go with the first pattern a+N.<br />

2) On the other hand, at is prevalent with the pattern pe+N, and also pis+ N.<br />

With respect to the patterns <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ite pronoun+noun, it is very hard to see which<br />

relative goes with what pattern. Numerically pat is more frequent with these types <strong>of</strong><br />

antecedents.<br />

1. a+N: pat (NAR) rpS Senec tellis how a philosophur pat hight Archisibus had a<br />

frendpat was both seke & pure. 37-20/ rnpS pis lepre man had a copp pat was<br />

passand like his copp 40-3/ nrps how pat a monk some <strong>of</strong> Ceustus ordur, pat was<br />

Celerer, was tempid with covatice 65-19/ nrnpS <strong>An</strong>d emang paim was a chefe ape,<br />

pat satt <strong>in</strong> a hye sete pat was ordand for hym 24-19. (DIS) rpS per was ayong<br />

man pat lukid on my fayrehede 14-25/ rnpR for a syn pat I was neuer shreuyn <strong>of</strong><br />

229-21.<br />

at (NAR) rpS per was a duke at had a wyfe pat liffed so delicatlie 170-24/ nrnpS<br />

sho was putt <strong>in</strong> a mervaLous grete comfurth, at contynued with hur lang & recedid<br />

noght away from hur 134-26/ rnpS she would go vnto a dike at was beside pe place<br />

27-13. (DS) rnpS par I hard a voyce at sayd vnto me 92-29/ rnpO I hafe yit <strong>in</strong> my<br />

mynde a little gude turn at pou did me with vsurie 43-5.<br />

2. 0+N: pat (NAR) rpS he garte gadur to-gedur yong men pat wer able vnto chyvalrie<br />

214-30/ rnpO for grete abst<strong>in</strong>cns pat he vssyd 19-22/ nrpS he on a tyme come<br />

vnto Philipp, pat was kyng <strong>of</strong> Romays 9-19. (DIS) rpS yone are devils pat begylis<br />

119-23/ rnpS hase pou not sene turment pat is for to come 21-3/ nrpS thankis<br />

God pat gaf me so fayr a form 237-13.<br />

at (NAR) rpS he put <strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong>fisurs at war hard <strong>of</strong> strayte 252-15/ rnpS be power at<br />

was gyffen vnto hym 82-24/ nrpS when Senec at was his maister askid hym 156-21.<br />

(DIS) rnpO with s<strong>of</strong>owle synys at pou sayd at he had done 124-4/ nrpR I am<br />

Saynt Nicholas at pou hase bene devote to 186-9.<br />

3. pe+N: pat (NAR) rpS pe kynges pat come <strong>of</strong> pe nowtherd kynred hase reigned<br />

vppon pe pepull & pe land <strong>of</strong> Brytany 254-27/ rnpS <strong>An</strong>d with a gude harte sent<br />

hym itt, pefyssck pathad coste hym xx d. 4-16/ nrpS he was war <strong>of</strong> pe devill<br />

syttand vppon pe hy altar <strong>in</strong> a chare, pat said vnto hym 199-3. (DIS) rpS for pe<br />

wommanpat was p<strong>in</strong>e oste yisternyght was so werie and so yrke 14-3/ rnpS pe<br />

prayers pat er prayed for pe er nott harde 106-10.<br />

at (NAR) rpS it happend at pe men att aght pis gude folowid after pis thefe 52-2/<br />

rnpS he drew at pe coverlad att lay on hym 230-9/ nrpR <strong>in</strong> pat was the goddis<br />

<strong>of</strong> Egypte, <strong>of</strong> golde & <strong>of</strong> syluer, at pis Assenech did sacryfice vnto 62-7/ rpS (DIS)

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 45<br />

Yonder is pe devull at cryes at the dure! 247-4/ rnpO Whar is now pe money att<br />

pou gaderd samen to lift with <strong>in</strong> p<strong>in</strong>e elde 64-20.<br />

4. Gen+N:pat (NAR) rpS <strong>An</strong>d onone per neghburpat did pis avowtr was vexid with<br />

a fend 27-1/ rnpR heturnyd agayn vnto hisfals error pat he was <strong>in</strong> be for 24-36/<br />

nrpO pan he mett with his thridfrend, pat he luffid bod litill 43-3. (DIS) nrpS att<br />

pe son sulde sla his modir pat sufferd so grete payn for hym <strong>in</strong> hur[burth as sho<br />

did, & broght hym yp with so grete labur 157-10/ at (NAR) rpR <strong>An</strong>d his furste<br />

frend at he come to & told pis matier ansswerd hym 43-19/ rnpS at pai mott hafe<br />

per doggis at kepid per shepefald delyverd 130-9/ nrnpO I saw pi neghbur sew at<br />

pou stale 187-16. (DIS) rnpO ioyes <strong>of</strong> his dignitie at he hase after hym 60-26/ rnpR<br />

Whar is now pi gay aray at pou was so prowde <strong>of</strong> 237-4.<br />

5. Superlative+N: pat (NAR) rnpO he tuke a gude hors, & pe beste clothis pat he<br />

had 6-12/ rnpO What was pe grettest mervayle & fayrest p<strong>in</strong>g pat evur God made<br />

<strong>in</strong> leste rowme 50-9. at (DIS) rnpO it sail be pe best chafir at evur pou boght<br />

108-20.<br />

6. Num+N: pat (NAS) rpO per was ij brether pat dwelte samen many yeris 118-24/<br />

rnpS he gaff hur for his rawson iiij castels pat er <strong>in</strong> pe bisshop ryk <strong>of</strong> Lunens<br />

155-13. (DIS) rpS yit ij sulde nott be fon to gedur pat war lyke <strong>in</strong> visage <strong>in</strong> all<br />

maner <strong>of</strong> thyng 50-13 (<strong>An</strong>tecedent=numeral)<br />

7. pat+N: pat (NAR) rpR Hym selfe was pat shipman pat he gaff pat syluer dish<br />

vnto 237-26/rnpS and make not sorow for pat p<strong>in</strong>g pat is verely loste & can never<br />

be requoverd 132-17 (DIS) rpS Bryng hedur pat lord <strong>of</strong> ours pat late seld hys pylgram<br />

clothyng & drank it 198-15/rnpR vnto pat ioj pat I was <strong>in</strong> 178-6.<br />

at (NAR) rnpO prayed pe abbott for to forgyff hym pat wrong at he had done<br />

vnto hym 10-21/ rnpO to gett pat p<strong>in</strong>g at he might not gett 132-16/ rnpS whatt<br />

he bare <strong>in</strong> pat sekk at was so hevy 104-17 (DIS) rnpO pat clothyng at pou gaff pe<br />

pure man, pou gaff it me 205-8/ rpS ff or pat womman at bad pe spyr me pies<br />

questions is pe devull 50-26.<br />

8. pase+N: pat (NAR) rpS for pase gude wommen patt gase on nyghtis 173-13/<br />

rnpR pat all pase membris pat he had servid pe devull with suld be cutt <strong>of</strong>f 34-29.<br />

at (NAR) rpO did penans for pase fals goddis at sho had wurshuppid 63-31.<br />

9. pis+N: pat (NAR) nrpS pis monk pat was deade apperid <strong>in</strong> a vision vnto his<br />

abbott 16-5/ nrpS <strong>An</strong>d pis abbatis, pat was grete with childe, made mekull sorow<br />

ll-25/ nrnpS pis horse, pat was so gaylie cled, was wayke & lene 237-1. (DIS) nrnpS<br />

Behold pis stane pat hyngis be for my face 31-22<br />

at (NAR) nrpS he mott venge hym on pis monke at had servid hym so evull 245-<br />

20/ nrnpS pis hemet mysside pis wulfe, at vsid to com daylie vnto hym, he made<br />

his prayer vnto God 232-28.<br />

10. thies+N: at (NAR) nrpO he putt oute pies <strong>of</strong>fisurs at hispredecessurhad ordand<br />

todo workis <strong>of</strong> mercy 252-12.

46 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> iri <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

ll. same+N: pat (DIS) <strong>of</strong> pe same <strong>of</strong>frand pat I made with myne awn handis 212-3.<br />

at (NAR) rnpO <strong>in</strong> pe same clothyng at sho had on 143-4. (DIS) rnpO pouerteput<br />

to pe same occupation at I vse 237-6.<br />

12. such+N: pat (NAR) rnpS per entred <strong>in</strong>to his harte suche a temptation pat, as<br />

hym thoght, rownyd vnto hym 80-18.<br />

13. no+N: pat (NAR) rpS per was no man pat kend nowderhis fadurnor his moder<br />

196-8/ nrnpS pat he sail nott here noo gude prechyng, pat sulde cauce hym to forsake<br />

his syn 67-8. (DIS) rnpS pat no suspecte rise betwix vs pat myght hurte pi<br />

gude name and pi fame 49-29.<br />

at (NAR) rpS scho would be giffen vnto no man at was <strong>in</strong>thraldom as Joseph was<br />

62-25/ rpO he cuthe know no man at he saw 195-30.<br />

14. any+N: pat (NAR) rpS nevur aftur presume to disese any creatur pat had<br />

deuocion vnto our ladie 54-26.<br />

15. some+N: pat (NAR) rnpS & trustid he had done som grete syn, pat causid his<br />

gudis to fall away from him 8-27.<br />

at (DIS) rnpO pis is som vision att God will shew vs 196-21.<br />

16. all+N: pat (NAR) rnpS & all p<strong>in</strong>g pat was made <strong>of</strong> leddur 220-13.<br />

at (NAR) rnpO he besoght hym to forgiff hym all <strong>of</strong>fensis at he had made vnto<br />

hym 152-16.<br />

17. many+N: at (NAR) rnpR per was a man pat had done many grete synys at he<br />

was neuer shrevyn <strong>of</strong> 125-12.<br />

18. (a)few+N: pat (NAR) rps he fandfew knightis pat was able vnto pe were 214-<br />

29. (DIS) he cuthe fynd nothyng <strong>of</strong> me bod afew gude dedis pat I did <strong>in</strong> my<br />

yowthed 21-23.<br />

19. a noder+N: pat (NAR) rpS per was... a noder religious womman pat saw all<br />

pis112-9.<br />

20. oper+N: pat (NAR) rpS per was oper privay Cristen men pat wrote per martirdom<br />

& put it betwix ij stonys 195-12.<br />

21. (euer-) ilk+N: pat (NAR) rpS ilk man or womman pat come <strong>in</strong> att his yate,<br />

pat was owder crukkyd-bakkid, skabbid, or pat had bod one ey, or war..., he sulde<br />

hafe <strong>of</strong> paim a penny 164-1.<br />

at (NAR) rnpO bod at euer-ilk wurd at he said, hed mynd <strong>of</strong> hur 250-28. (DIS)<br />

rnpO pou sulde not trow euer-ilk wurd att pou hard 132-32.<br />

22. yone+N: pat (NAR) rpS Yone yoog man pat is so prowde & full <strong>of</strong> syn, stynkis<br />

morvglie <strong>in</strong>pe sight <strong>of</strong> God 51-21/ rpS Wold God at I mott se yone aide man<br />

deade, pat is Emperour 68-4.<br />

5. 7. Pronoun <strong>An</strong>tecedents Table XII shows the frequencies <strong>of</strong> pronouns used as relative<br />

antecedents <strong>in</strong> the text exam<strong>in</strong>ed.

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 47

48 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

The pronouns used here may be grouped <strong>in</strong>to three k<strong>in</strong>ds: personal, demonstrative and<br />

<strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ite. There are found some cases <strong>in</strong> which two k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> pronouns are put together,<br />

e. g. he pis.32<br />

From the figures <strong>of</strong> the above table, the follow<strong>in</strong>g significant facts emerge:<br />

1) Generally speak<strong>in</strong>g, personal pronoun antecedents prefer pat to at, show<strong>in</strong>g the ratio<br />

<strong>of</strong> pat 61 to at 28 <strong>in</strong>NAR and 31 to 10 <strong>in</strong> DIS. Indef<strong>in</strong>ite pronouns also tend to ocurr<br />

with pat, the ratio be<strong>in</strong>g 60:25 <strong>in</strong> NAR and 3:2 <strong>in</strong> DIS, while on theother hand demonstrative<br />

pronouns have a reversed tendency, the figures be<strong>in</strong>g 3:10 <strong>in</strong> NAR and 0:14 <strong>in</strong><br />

DIS.<br />

2) In the case <strong>of</strong> third person s<strong>in</strong>gular and plural forms, the frequencies are different;<br />

he and pai prefer pat. With pa<strong>in</strong>t both pat and at are frequent.<br />

3) With demostrative pat, at is def<strong>in</strong>itely preferred. Compare with pat <strong>in</strong> a noun<br />

antecedent. It is quite natural to avoid the comb<strong>in</strong>ation pat pat from the standpo<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong><br />

euphony. <strong>An</strong>other demonstrative pis also seems to take at <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> pat.<br />

a) Personalpronouns: pat (NAR) I nrpS how wrichid & vnhappie am /, pat hase<br />

done so mekull as I hafe done 7-13/ thou nrpS Thou ert pat man, pat at fals suggestion<br />

<strong>of</strong>f pi wife slew my husband 155-5/ he rpS he pat saw pe vysion answerd<br />

86-18/hym rpS desirid his brethir to make hym pat was his sybman Abbott 7-32/<br />

his rpS at pis shepe sulde blete <strong>in</strong> his belie pat had etyn it 232-13/ sho nrpS <strong>An</strong>d<br />

when sho pat before was ferd for hur dead hard pis 117-34/ hur nrpS becauce pai<br />

turment hur, pat was a womman<strong>of</strong> so gude coversacion & penance 23-35/ it rpS it<br />

was pe fend pat garte pe erth stir 170-6/ pai rpS & pai pat dwelte <strong>in</strong> paim was<br />

destroyed 253-18/ paim rpS agayns paim pat wull here no thyng bod at is to per<br />

plesur 25-3. (DIS) I nrpS /, pat am your lord, mon now dy 68-29/ my nrpS will<br />

eatt <strong>of</strong> my bread pat am cursyd 215-18/ me nrpS What may shrifte pr<strong>of</strong>ett me, pat<br />

hase done so manygrete trispasis 57-20/ we rpS & we pat sulde be your brethir fare<br />

neuer so ill5-10/ vs nrpS & take vs <strong>in</strong>, pat er cullid with grete ioj &myrth 241-13/<br />

pou nrpS pou pat ert boun with syn 35-26/ pe nrpS God blis pe pat whikkens<br />

all creatures 63-22/ ye nrpS for ye pat er no better pan myselfe, is bod evynlyngis<br />

with me 29-17/ he rpS He pat is curste, go his ways! 216-7/ hym rpS vnto hym<br />

patt did pis dede! 118-18/ paim rpS If we sla paim pat luffis vs, what sulde wedo<br />

withpaim atthatis vs 44-4/ pai rpS pai pat er pi frendis sal be p<strong>in</strong>eenmys 68-ll.<br />

at (NAR) he rpS he att told itt, askid hym 154-ll/hym rpS ane <strong>of</strong> paim steppyd<br />

be for hym at satt 159-15/ it rnpO he was redie to pr<strong>of</strong>e it at he had told hym 154-<br />

12/ pai rpS pai att wer aboute hym askid hym 207-7/ paim rpS he garte kyllpaim<br />

pat did no truspas, with paim at did pe trispas 35-14/ per rpS <strong>in</strong> grapyng <strong>of</strong> per<br />

vaynys at war seke 74-22. (DIS) pou nrpS pou, at yit ete no p<strong>in</strong>g, says now at pou<br />

may nogt eate 254-4/ the nrpO sho saw neuer man bod me & the at sho saw pis<br />

day 63-13/ sho rpO her is sho at pou hase accusid 222-4/ it nrnpO and pis is it at<br />

I am cled <strong>in</strong> 205-8/ paim rnpS killid paim at satt vppon his wownd 72-26.

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 49<br />

b) Demonstrative pronouns: pat (NAR) pat rnpO how pat was taken frohur pat God<br />

had giffen sho told hym 113-19/ po rpS po Pat callid hym lord, he was passand<br />

wrothe with paim 25-12.<br />

at (NAR) pis nrnpS pou ert <strong>in</strong>nocent<strong>of</strong>pis at is put on the 25-27/ pat rnpR sho<br />

was <strong>in</strong>nocent <strong>of</strong> pat at sho was accusid <strong>of</strong> 12-19/ (DIS) pis nrpO pis is not my<br />

Lord at ye hafe broght 212-26/ that rnpS That at was myne, God hase takenit fro<br />

me 168-23/ he pis nrpS sen he pis at did bod make a lye hase had suche a grete<br />

reward 24-27/ nrpS pat he this at lies here had neuer will <strong>in</strong> all his life to here pe<br />

wurd <strong>of</strong> Godd 67-20/ nrpO he pis att pou vpbraydid right now w<strong>in</strong> so fowle synnys<br />

124-3.<br />

c) Indef<strong>in</strong>ite pronouns: pat (NAR) none rpS per was none pat was more religious<br />

pan he was 183-1/ one rpS Valerius tellis <strong>of</strong> one pat was a passand famos poett 87-7/<br />

som rpSyit som pat was onhis syde fell <strong>in</strong> tone vnto hym 88-2/ all rnpO pai<br />

knew at all pat he said was trew 234-5/ any thyngr rnpO if per war any tkyng<br />

pat hymselfe wold grawnt to doo for penance 240-22/ a noder rpS per was sent a<br />

noder pat was les <strong>of</strong> connyng <strong>of</strong> literatur 217-ll/ pe toder rpS <strong>An</strong>d pe toder pat<br />

satt aboute gaff it 215-21/ other rpS as he did other <strong>of</strong> his brether pat dyed 15-8/<br />

all oper rpS and all oper pat hard ever after was ferd to stele 232-15. (DIS) one<br />

rpS outtakyn one pat is bod a fule 224-2/ all rpS all pat er<strong>in</strong>the cetie <strong>of</strong> Athenys<br />

130-17/ other rnpS pat other pat er hongry suld com & pryk 73-2.<br />

at (NAR) none rpS per was none att callid hym 138-24/ noght rnpO wuld com no<br />

ner for noght at no man cuthe do 54-ll/ one rpS one at was per said vnto this<br />

man at was bun 124-1/ all rpS he told all att was abowte hym how it had happend<br />

hym 234-3/ nothyng rnpO for nothyng att he cuthe say 114-10/ none oper rpS<br />

so did none oper att was per 125-5/ ilkone rpS vpbrayd ilkone at come <strong>in</strong> 123-17.<br />

(DIS) nothyng rnpS nor desire nothyng att is gude nor pr<strong>of</strong>etable vnto my selfe<br />

177-22.<br />

5. 8. The results <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>vestigation so far carried may be said to give evidence that<br />

there is some differentiation <strong>in</strong> function between pat and at <strong>in</strong> this Northern text.<br />

The results will be summarized as follows:<br />

1) There may be some difference <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic level between the two forms. At may<br />

be more colloquial and <strong>in</strong>formal.<br />

2) As a relative without an antecedent, at is the norm.<br />

3) The ma<strong>in</strong> job <strong>of</strong> pat is <strong>in</strong> personal/ subject function. Contrary to it at is <strong>in</strong> nonpersonal/object<br />

function.<br />

4) With noun antecedents, pat is preferred when they take the patterns a+N, 0+N<br />

and Num+N, while at is preferred with the patterns pe+N, and pis+N.<br />

5) When pronoun antecedents are personal pronouns, and <strong>in</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ite pronouns, pat is<br />

frequent. On the other hand with demonstrative pronouns at is prevalent. Especially<br />

pat at is the norm, pat pat avoided.

50 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

Notes<br />

1. See Middle English Dictionary, Plan and Bibliography, 1954, p. 12.<br />

2. Cf. I. A. Gordon, The Movement <strong>of</strong> English Prose (Longmans, 1966), p. 62 : "...racily told<br />

colloquial stories.... the language and sentence-structure <strong>of</strong> the short story are completely native."<br />

3. Only one example is found <strong>in</strong> the text. (NAR) This is gude to tell agayn flaterers, &<br />

agayns paim pat wull here no thyng bod at is to per plesur. 25-5. This may or may not be<br />

relatival. Baldw<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong>fers some examples <strong>of</strong> relative but <strong>in</strong> The Inflections and Syntax <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Morte D'Arthur <strong>of</strong> Sir Thomas Malory (Boston, 1894), § 361, but OED (but 12) and Visser,<br />

<strong>An</strong> Historical Syntax <strong>of</strong> the English Language, Vol. I (Leiden, 1963), § 20 give no examples<br />

previous to 1500. See also A. C. Partridge, Studies <strong>in</strong> the Syntax <strong>of</strong> Ben Jonson's Plays<br />

(Cambridge, 1953), p. 64.<br />

4. These numbers show the page and l<strong>in</strong>e where the example appears.<br />

5. Cf. Curme, Syntax, p. 204f ; Yamakawa, "Renketsushi Hattatsu no Nikeiretsu," Studies <strong>in</strong><br />

English Literature, XXVI. ii ; Jespersen, MEG, III, 4. 31.<br />

6. Cf. Brunner, Die Englische Sprache, II, p, 152 ; Mustanoja, Middle English Syntax, Pt. I,<br />

p.191.<br />

7. EETS, ES 33 (1879). Moralities are excluded from my exam<strong>in</strong>ation.<br />

8. For details see my article "<strong>Relative</strong> Constructions <strong>in</strong> The Book <strong>of</strong> Margery Kempe", Bullet<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> Nara University <strong>of</strong> Education, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1969).<br />

9. Studien zur Syntax des Nomens, Pronomens und der Negation <strong>in</strong> den Paston Letters, Bochum-Langendreer,<br />

1959, p. 249ff. WAo-compounds are not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the count<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

10. The follow<strong>in</strong>g statistics <strong>of</strong> other works byW<strong>in</strong>kler, Das Relativum bei Caxton und se<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Entwicklung von Chaucer bis Spenser (Diss. Berl<strong>in</strong>, 1933) will be a help for our further<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the situation <strong>of</strong> the relatives<br />

that which + (the which)=<br />

Chaucer, 1000VV. 80.5^ ; ll.2& =17.5#<br />

Cant- T- (+6.3^ which that)<br />

M , (Kap. 1-6 83.4

<strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito) 51<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

14. See Mustanoja's remark, (.op. cit., pp. 204-5) : "They (sc. contact-clauses) make their appearance<br />

<strong>in</strong> the second half <strong>of</strong> the 14th century... It occurs more frequently <strong>in</strong> poetry than <strong>in</strong><br />

prose." See also Visser, op. cit., § 629 ; Ryden, <strong>Relative</strong> Constructions <strong>in</strong> Early Sixteenth<br />

<strong>Century</strong> English (Uppsala, 1966), p. 267ff. notes. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Ryden's notes, 0 as subject<br />

does not occur <strong>in</strong> Pecock, are rare <strong>in</strong> Capgrave, and extremely rare <strong>in</strong> Caxton. In Malory<br />

and the Paston Letters it is mostly used <strong>in</strong> connection with there is/are. 0 as object is rare<br />

<strong>in</strong> Pecock, Fortescue, Caxton, and the CelyPapers. It is more common <strong>in</strong> Capgrave, as it is<br />

<strong>in</strong> Malory and the Paston Letters.<br />

15. NAR DIS<br />

GR 6 2<br />

MK 21 10<br />

16. See Reuter, "Some Notes on the Orig<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Relative</strong> Comb<strong>in</strong>ation the which" Neuphilologische<br />

Mitteilungen 38 (1938), pp. 146-188.<br />

17. Op. cit., p. 199.<br />

18. Die Entwicklung der englischen Relativpronom<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> spatmittel-englischer und friihneuenglischer<br />

Zeit (Diss. Breslau, 1932), p. 72 : "E<strong>in</strong> kurzer Ueberblick zeigt, dass <strong>in</strong> der volkstiimlichen<br />

Sprache des 15. Jahrhunderts die Verb<strong>in</strong>dung the which sehr haufig ist."<br />

19. See the follow<strong>in</strong>g data:<br />

MK<br />

<br />

<br />

NAR<br />

DIS<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

GR<br />

<br />

<br />

In MK restrictive which is already established <strong>in</strong> both categories, while pe which is more<br />

non-restrictive. In GR pe which is predom<strong>in</strong>antly non-restrictive.<br />

20. See the figures below:<br />

GR<br />

{ which<br />

pe which<br />

(which<br />

[pe<br />

which<br />

p<br />

157<br />

29<br />

69<br />

2<br />

NAR<br />

np<br />

72<br />

32<br />

32<br />

6<br />

p<br />

24<br />

7<br />

1<br />

DIS<br />

np<br />

19<br />

7<br />

24<br />

7

52 <strong>Relative</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>An</strong> <strong>Alphabet</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tales</strong>, a <strong>Fifteenth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> Northern Text (Saito)<br />

21. See §2. 1. <strong>of</strong> this paper.<br />

22. Op. cit.t p. 252.<br />

23. Op. cit.y p. 3. See also Mustanoja, op. cit., p. 199.<br />

24. A Syntax <strong>of</strong> the English Language <strong>of</strong> St. Thomas More, Pt. 1 (Louva<strong>in</strong>, 1946), §197.<br />

He adds <strong>in</strong> the section that accord<strong>in</strong>g to E<strong>in</strong>enkel this formula is an imitation <strong>of</strong> Old French<br />

"come qui die Modern French comme qui dirait.<br />

25. Op. cit., p.201.<br />

26. See the follow<strong>in</strong>g figures :<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

27. Op. cit., p. 195.<br />

28. Op. cit., p. 67. See also Ryden, o£. c;7,, p. 338: "Clear <strong>in</strong>stances <strong>of</strong> relative what are<br />

comparatively rare <strong>in</strong> Elyot's writ<strong>in</strong>gs."<br />

29. "The <strong>Relative</strong> Pronuns pe and pat <strong>in</strong> Early ME," English and Germanic Studies I, (1947-<br />

8), PP. 73-87. For the outl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> this paper see Mustanoja, op. cit., p. 189.<br />

30. This is quite natural because <strong>in</strong> ACTOR-ACTION-GOAL relation the actor would most<br />

frequently be a person, the goal be<strong>in</strong>g a th<strong>in</strong>g. The same result as this is observed <strong>in</strong> MK.<br />

See §4.0 <strong>of</strong> my paper referred to <strong>in</strong> Note 8.<br />

31. With respect to relatives <strong>in</strong> front-position see Ryden, op. cit. p. 323ff.<br />

32. For this comb<strong>in</strong>ation he pis see Visser, op. cit. (1963), §74:also' Mustanoja, op. cit.,<br />

P.137.