2010 Annual Report: Education - PartnershipsInAction

2010 Annual Report: Education - PartnershipsInAction

2010 Annual Report: Education - PartnershipsInAction

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

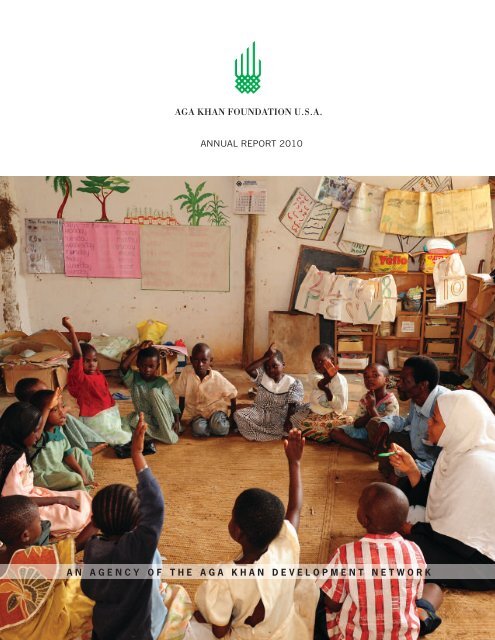

AGA KHAN FOUNDATION U.S.A.<br />

ANNUAL REPORT <strong>2010</strong><br />

A N A G E N C Y O F T H E A G A K H A N D E V E L O P M E N T N E T W O R K

In the Osh Oblast of the Kyrgyz Republic,<br />

AKF seeks to improve early childhood development<br />

by establishing a network of<br />

kindergartens (both central and satellite for<br />

the more remote villages) supported by<br />

teacher training and relevant learning<br />

materials.

Dear friends,<br />

As another year ends, we reflect on the accomplishments of <strong>2010</strong> and look forward to progress<br />

in the future. Last year, we acquired almost $18 million in new grant funding and raised $7.8<br />

million at our annual fundraisers held throughout the US. With the total $25 million, we were<br />

able to improve the lives of millions of men, women and children in Africa and Asia. Pregnant<br />

mothers in Pakistan now have access to midwives and inexpensive healthcare; drought-ridden<br />

farmers in Kenya are growing more crops and marketing them more efficiently; and girls in<br />

Afghanistan are now receiving the education they deserve.<br />

Aziz Valliani<br />

Chairman<br />

National Committee<br />

As established by His Highness the Aga Khan many years ago, the Aga Khan Foundation is<br />

unwavering in its commitment to combat illiteracy, ill health and poverty. In partnership with<br />

other Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) agencies, the Foundation pursues this mission<br />

with confidence. The AKDN is rooted in the developing world with a history, permanency and<br />

sustainability that few others are able to match.<br />

In the vast portfolio of development work and community needs, nothing is more important to<br />

the long-term sustainability and health of a community than ensuring access to education – the<br />

focus of this year’s annual report. We all know that education improves livelihoods and builds<br />

achievement all over the world, but there is increasing recognition of education as a much<br />

greater and more integrated tool. As we continue this quest for a better and safer world, we have<br />

found that education generates good citizenship, promoting greater tolerance and creating<br />

pluralism in human societies. <strong>Education</strong> has become, in essence, a foundation for peace.<br />

Dr. Mirza Jahani<br />

Chief Executive Officer<br />

We have learned over the years not to become frightened by the complexities of the development<br />

process but to embrace the challenges and the multiple inputs required. In this report, we<br />

invite you to stretch your thinking, offer feedback and reflect on the challenges faced every day<br />

by the work of the Foundation. We have changed the format of our report to have one main<br />

‘thought’ piece, addressing a central development issue: how a child transitions from home to<br />

preschool to primary school and onwards. What are the challenges presented to the child, the<br />

educators, the family and the community What are the critical factors that support this<br />

transition especially in the early formative years What are the policy implications What is your<br />

own experience with your child This new approach, with articles from recognized leaders in<br />

the field, will become a regular feature of our annual report, complementing our usual annual<br />

progress update. This year, we are pleased to have contributions from Robert Myers and Dr.<br />

Sharon Lynn Kagan, both known experts in childhood education.<br />

No message would be complete without noting our most heartfelt gratitude to the huge numbers<br />

of individual, corporate and institutional supporters of Aga Khan Foundation U.S.A. as well as<br />

our volunteers whose commitment stands as a backbone for many of our outreach activities.<br />

Our current portfolio remains at a stable $65 million and is now set to grow in 2011 and<br />

beyond. This would not be possible without your generosity. Thank you.

O v e r v i e w<br />

Aga Khan Development Network<br />

Founded and guided by His Highness the Aga Khan, the Aga Khan<br />

Development Network (AKDN) brings together a number of international<br />

development agencies, institutions and programs that work primarily in the<br />

poorest parts of South and Central Asia, Africa and the Middle East. All AKDN<br />

agencies conduct their programs without regard to faith, origin or gender.<br />

AKDN consists of the following agencies:<br />

The Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) is a non-denominational, international<br />

development agency established in 1967 by His Highness the Aga Khan. Its<br />

mission is to develop and promote creative solutions to problems that impede<br />

social development, primarily in Asia and East Africa. Created as a private,<br />

non-profit foundation under Swiss law, it has branches and independent<br />

affiliates in 20 countries. Aga Khan Foundation U.S.A. was established in<br />

1981 and is based in Washington, DC.<br />

The Aga Khan Agency for Microfinance (AKAM) works to expand access<br />

for the poor to a wider range of financial services, including micro-insurance,<br />

small housing loans, savings, education and health accounts. Its programs<br />

range from village lending cooperatives to self-standing microfinance banks in<br />

South and Central Asia, Africa and the Middle East.<br />

Aga Khan <strong>Education</strong> Services (AKES) aims to diminish obstacles to<br />

educational access, quality and achievement. It operates more than 300<br />

schools and advanced educational programs at the preschool, primary,<br />

secondary and higher secondary levels in Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Kyrgyz<br />

Republic, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Tanzania and Uganda. It emphasizes studentcentered<br />

teaching methods, field-based teacher training and school<br />

improvement.<br />

Top: AKDN has worked in partnership with<br />

Afghan communities since 2002.<br />

Middle: The First MicroFinanceBank Pakistan,<br />

an institution of Aga Khan Agency for Microfinance,<br />

offers credit, savings, life insurance services<br />

and low cost funds-transfer services as a<br />

means to alleviate poverty.<br />

Bottom: Over 2.5 million people have benefited<br />

directly from the AKF’s rural support<br />

programs worldwide in over 8,400 village<br />

organizations.<br />

Aga Khan Health Services (AKHS) provides primary and curative health<br />

care in Afghanistan, India, Kenya, Pakistan, Tajikistan and Tanzania in over<br />

200 health centers, dispensaries, hospitals, diagnostic centers and community<br />

health outlets. <strong>Annual</strong>ly, AKHS provides primary health care to 1.8 million<br />

beneficiaries and handles 1.5 million patient visits. AKHS also works with<br />

governments and other institutions to improve national health systems.<br />

Aga Khan Planning and Building Services (AKPBS) assists communities with<br />

village planning, natural hazard mitigation, environmental sanitation, water supply<br />

systems and improved design and construction of both housing and public<br />

buildings. It provides material and technical expertise, training and construction<br />

management services to rural and urban areas.

The Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) encompasses the triennial Aga Khan<br />

Award for Architecture; the Historic Cities Program, which undertakes<br />

conservation and rehabilitation in ways that act as catalysts for development;<br />

the Music Initiative, which preserves and promotes the traditional music of Central<br />

Asia, Middle East, North Africa and South Asia; ArchNet.org, an online archive<br />

of materials on architecture and related issues; the Aga Khan Program for Islamic<br />

Architecture, which is based at Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute<br />

of Technology; and the Museums Project, which is creating museums in Toronto<br />

and Cairo.<br />

The Aga Khan University (AKU) is a major center for education, training<br />

and research. Chartered as Pakistan’s first private international university in<br />

1983, it has teaching sites in Afghanistan, Kenya, Pakistan, Syria, Tanzania,<br />

Uganda and the United Kingdom. Following the establishment of the Faculty<br />

of Health Sciences, the Institute for <strong>Education</strong>al Development and the Institute<br />

for the Study of Muslim Civilisations, AKU is moving towards becoming a<br />

comprehensive university with a Faculty of Arts and Sciences in Karachi.<br />

The University of Central Asia (UCA), chartered in 2000, is located on<br />

three campuses: Khorog, Tajikistan; Tekeli, Kazakhstan; and Naryn, Kyrgyz<br />

Republic. UCA’s mission is to foster economic and social development in the<br />

mountain regions of Central Asia. It will offer Master of Arts degrees in<br />

mountain development; a Bachelor of Arts program based on the liberal arts<br />

and sciences; and non-degree continuing education courses.<br />

The Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development (AKFED) is the only forprofit<br />

agency in the Network. Often acting in collaboration with local and<br />

international partners, the Fund takes bold but calculated steps to invest in<br />

fragile and complex settings. AKFED mobilizes investment for the construction,<br />

rehabilitation or expansion of infrastructure; sets up sustainable financial<br />

institutions; builds economically viable enterprises that provide essential goods<br />

and services; and creates employment opportunities.<br />

The Aga Khan Academies (AKA), an integrated network of schools, are<br />

dedicated to expanding access to education of an international standard of<br />

excellence. The Academies, which will educate young men and women from<br />

pre-primary through higher secondary education, are planned for key locations<br />

in Africa and Asia. The first such school, the Aga Khan Academy in Mombasa,<br />

began operating in August 2003.<br />

Top: Al-Azhar Park, a project of the Aga Khan Trust for<br />

Culture, has proven to be a powerful catalyst for urban<br />

renewal in Darb al-Ahmar, one of the poorest districts<br />

in Cairo.<br />

Middle: Frigoken, an AKFED project company, supports<br />

over 45,000 small scale farmers in rural Kenya.<br />

Bottom: The Aga Khan Academies is dedicated to expanding<br />

access to education of an international standard<br />

of excellence.

In earthquake-prone regions of northern<br />

Afghanistan, the Community Based Disaster<br />

Risk Reduction project mobilizes emergency<br />

response teams among students and community<br />

members and trains them in disaster preparedness.<br />

It is a project of the AKF USA and<br />

Focus Humanitarian Assistance, funded by the<br />

US Agency for International Development.<br />

Focus Humanitarian Assistance provides emergency relief supplies and<br />

services to victims of conflict and natural disasters. It also works with AKF to<br />

help people recover from these events and make the transition to long-term<br />

development and self-reliance. AKDN institutions work together with the<br />

world’s leading aid and development agencies.<br />

Aga Khan Foundation U.S.A.<br />

Aga Khan Foundation U.S.A. (AKF USA), established in 1981 in Washington,<br />

DC, is a private, non-denominational, not-for-profit international organization<br />

committed to the struggle against hunger, disease and illiteracy, primarily in<br />

Africa and Asia. The Foundation works to address the root causes of poverty by<br />

supporting and sharing innovative solutions in the areas of health, education,<br />

rural development, civil society and the environment. Using community-based<br />

approaches to meet basic human needs, the Foundation builds the capacity of<br />

community and non-governmental organizations to have a lasting impact on<br />

reducing poverty.<br />

AKF USA’s role within AKDN includes mobilizing resources and strategic<br />

partnerships with a variety of US-based institutional partners including<br />

government agencies, policy institutes, corporations, foundations, NGOs,<br />

universities, associations and professional networks. AKF USA serves as a<br />

learning institution for program enhancement, policy dialogue and disseminating<br />

best practices and knowledge resources. It collaborates in providing technical,<br />

financial and capacity-building support to other AKDN agencies and programs<br />

worldwide. In facilitating and representing AKDN interests in the US, AKF USA<br />

organizes outreach campaigns, manages volunteer resources and conducts<br />

development education among US constituencies.

A G A K H A N D E V E L O P M E N T N E T W O R K<br />

THE IMAMAT<br />

AGA KHAN DEVELOPMENT NETWORK<br />

ECONOMIC<br />

DEVELOPMENT<br />

SOCIAL<br />

DEVELOPMENT<br />

CULTURE<br />

Aga Khan Fund for<br />

Economic Development<br />

Aga Khan Agency<br />

<br />

Aga Khan<br />

Foundation<br />

Aga Khan<br />

University<br />

University of<br />

Central Asia<br />

Aga Khan Trust<br />

for Culture<br />

Tourism Promotion<br />

Services<br />

Industrial Promotion<br />

Services<br />

Aga Khan <strong>Education</strong> Services<br />

Aga Khan Health Services<br />

Aga Khan Award<br />

for Architecture<br />

Aga Khan Historic<br />

Cities Programme<br />

Financial Services<br />

Media Services<br />

Aga Khan Planning and<br />

Building Services<br />

Aga Khan<br />

Music Initiative<br />

Museums &<br />

Exhibitions<br />

Aviation Services<br />

Aga Khan Academies<br />

Focus Humanitarian Assistance<br />

The AKDN is the largest private international network of its kind. AKDN agencies are comprised of both nonprofit and commercial forprofit<br />

entities. The Network brings together a number of agencies, institutions and programs that have accumulated an extensive history<br />

of experience in social, economic and cultural development. Each agency has a particular mandate and expertise, ranging from the<br />

environment, health, education, architecture, culture, microfinance, rural development, disaster reduction, the promotion of privatesector<br />

enterprise and the revitalization of historic cities.

T h e m e : E d u c a t i o n – T h e Un i v e r s a l B r i d g e<br />

Each year Aga Khan Foundation U.S.A. (AKF USA) explores international<br />

development issues via a specific theme that is significant to the Foundation’s<br />

focus areas in health, education, rural development, civil society and the<br />

environment. Our theme, <strong>Education</strong>: The Universal Bridge, underscores the<br />

importance of Aga Khan Foundation’s enduring commitment to educational<br />

institutions and capacity-building efforts in Africa and Asia. Two articles by<br />

education experts are included in this year’s report to explore in greater depth<br />

the issues related to children's transition to school (see section "Development<br />

Solutions with Lasting Impact").<br />

<strong>Education</strong> serves as a bridge to help individuals and communities build more<br />

productive, fulfilling and dignified lives. The Foundation’s educational activities<br />

span across a broad range of initiatives to help people in Asia and Africa reach<br />

their full potential from early childhood development to primary and secondary<br />

school improvement to skills and management training for professionals,<br />

entrepreneurs and community members. Health-related activities include<br />

training nurses and educating communities about disease prevention and<br />

healthy behaviors. Rural development programs teach farmers effective<br />

techniques to help them move beyond subsistence. All of these efforts equip<br />

people with life-long skills to overcome poverty and build healthy, self-reliant<br />

and dignified lives.<br />

AKF USA has a growing portfolio in education with generous support from<br />

institutional donors such as the US Agency for International Development,<br />

The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and International Youth<br />

Foundation, among others. The Foundation also works in close collaboration<br />

with its sister AKDN agencies to implement programs on the ground. The<br />

following exemplify the range of our educational programs.

Early Childhood Development (ECD). AKF has been a pioneer in promoting<br />

ECD for decades. With its child-centered approach and culturally appropriate<br />

curricula, AKF’s model East Africa preschool program has grown to over 200<br />

preschools, training 6,000 teachers and 3,000 school management<br />

committee members and reaching over 60,000 children.<br />

Training Nurses. Nurses form the front line of rural healthcare, often serving<br />

as the first and only point of contact for health services in developing countries.<br />

AKDN has established training programs in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Syria and<br />

throughout East Africa to improve skills and qualifications as well as expand<br />

the pool of qualified nurses.<br />

Opposite page: A nursing teacher from Aga<br />

Khan University in Karachi, Pakistan trains<br />

students in the nursing program in<br />

Afghanistan. An AKF agriculturalist trains<br />

Afghan farmers in better farming techniques<br />

and promotes the use of seed banks.<br />

Above: At Learning Resource Centers in<br />

Tajikistan, teachers are guided in child-centered<br />

teaching methods and learn to make<br />

low-cost learning aids to enrich lessons.<br />

School Improvement and Teacher Training. AKDN operates more than<br />

300 schools and programs that provide quality preschool, primary, and<br />

secondary education services to students in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India,<br />

Bangladesh, Kenya, the Kyrgyz Republic, Uganda, Tanzania, and Tajikistan.<br />

Professional Development Centers provide world-class training to boost a<br />

growing cadre of competent, inspiring teachers.<br />

Building Skills and Knowledge among Rural Populations. In most areas<br />

where the Foundation works, agricultural production is the primary economic<br />

activity for a majority of the people. The Foundation trains farmers in improved<br />

agricultural techniques to expand yields and productivity, which in turn,<br />

improve food security and incomes.

At the Teachers Resource Centers in Tanzania,<br />

teachers participate at an in-service<br />

training workshop and are provided with a<br />

forum to discuss issues of professional<br />

interest.<br />

Excellence in <strong>Education</strong>: Academies and Universities. Aga Khansponsored<br />

academies and universities such as the Aga Khan Academies, the<br />

University of Central Asia and the Aga Khan University create new educational<br />

models, with a vision to promote competent indigenous young leaders as a key<br />

to progress in the developing world.<br />

Community Outreach in the US. Across America, AKF USA volunteers reach<br />

out through grassroots initiatives that educate communities about the positive<br />

role they can play in solving global poverty. AKF USA’s educational initiatives<br />

seek to inform, inspire and unite Americans as “global citizens” with<br />

communities in Africa and Asia to build bridges of hope and to promote peace,<br />

pluralism, prosperity and security globally.

Ye a r i n R e v i e w : E d u c a t i o n<br />

A leading development priority for the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) is the<br />

promotion of quality education for all. From early childhood development to<br />

higher education, AKF is ensuring that marginalized groups – girls, the<br />

economically disadvantaged, physically challenged and geographically remote<br />

– are able to access quality education, stay in school longer and attain higher<br />

academic achievements.<br />

In Sub-Saharan Africa, half of children do not complete five years of primary<br />

school. Globally, India and Pakistan account for 30 percent of out-of-school<br />

primary aged children. These are the environments in which the Foundation<br />

works.<br />

AKF USA partners with other AKDN agencies<br />

as well as non-governmental organizations,<br />

civil society groups and governments<br />

to implement effective education programs.<br />

Ensuring that education is accessible is only half of the battle. A good<br />

education is not defined by mere access to a classroom or a teacher. With<br />

relevant curriculums, more engaging learning environments and dynamic<br />

teaching methods, children leave AKF classrooms better prepared to tackle<br />

life’s most challenging issues – whether that means providing for a family,<br />

starting a business or leading a community.<br />

Strengthening partnerships goes hand-in-hand with strengthening education<br />

systems. By facilitating better links between governments and school boards<br />

and parents and teachers, the Foundation uses the power of partnerships to<br />

ensure its education programs are long-lasting. AKF partners with other<br />

agencies within the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) as well as other<br />

non-governmental organizations, civil society groups and governments to<br />

implement effective education programs.

y e a r i n r e v i e w : e d u c a t i o n<br />

Improving the Quality of Early Learning in East Africa<br />

PROBLEM: High Dropout Rates and Poor Learning Outcomes in Grades 1-3<br />

After East Africa introduced free primary education for all, students flooded<br />

schools that were already struggling with a limited number of teachers and<br />

resources. In Uganda, enrollment increased from 2.6 million to 7 million, and<br />

Kenya gained nearly 2 million new students. With large classroom sizes and<br />

minimal teaching materials, many children were not receiving a quality<br />

education. Dropout rates rose with the lack of interactivity and attention from<br />

teachers. Students were simply unable to keep up with the curriculum. In<br />

Uganda, for example, one third of enrolled students drop out in first grade.<br />

Many of those who remain in school do not reach expected levels of<br />

competency in reading and mathematics. 1<br />

AKF USA, in partnership with The William<br />

and Flora Hewlett Foundation, is implementing<br />

the Reading to Learn instructional model<br />

in 115 schools in Kenya and Uganda to improve<br />

reading and math comprehension<br />

among students in grades 1-3.<br />

This education crisis begins specifically in early primary years – the most<br />

crucial time for a child’s social and intellectual development. Half of Africa’s<br />

children do not complete five years of primary school, negatively impacting<br />

their education and abilities for the rest of their lives.<br />

SOLUTION: East Africa Quality in Early Learning Program<br />

Aga Khan Foundation has been a pioneer in promoting early childhood<br />

development (ECD) for three decades and has been a leading partner in the<br />

Consultative Group on Early Childhood & Development. In 2007, AKF USA,<br />

in partnership with The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, established the<br />

East Africa Quality in Early Learning (EAQEL) Research and Development<br />

project. EAQEL is combining innovative education approaches with monitoring<br />

and impact evaluation techniques to measure the program’s effectiveness at<br />

improving literacy and math skills. The successes of this program may<br />

eventually be adopted by the Governments of Kenya and Uganda for broader<br />

impact throughout their education systems.<br />

The program is benefiting 64 primary schools in Kenya and 51 primary<br />

schools in Uganda. In each school, the project focuses on improving the<br />

classroom environment, providing learning materials and books, encouraging<br />

parents to get more involved, and increasing dialogue among key stakeholders.<br />

To support the delivery of curriculum in grades 1–3, teachers at the 115<br />

schools were trained to use the Reading to Learn education approach – a<br />

step-by-step way to teach literacy and numeracy that encourages active<br />

1 National Assessment for Primary <strong>Education</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, 2006.

y e a r i n r e v i e w : e d u c a t i o n<br />

learning. To help facilitate this transition, School Management Committee<br />

members and parents also learn about their roles to become more active in<br />

supporting children’s learning.<br />

Schools procured practice books and mini libraries, allowing children to get<br />

more involved in each lesson and encouraging reading outside the classroom.<br />

In the first year, 82 percent of learners in Kenya borrowed and read books from<br />

mini libraries. Additionally, newly established community libraries have helped<br />

increase parental involvement by giving parents access to learning materials.<br />

After structured coaching, parents now understand the importance of taking<br />

an active part in their child’s education by reading with their children,<br />

storytelling and encouraging homework. Seventy percent of the 1,200 trained<br />

parents in Kenya and 60 percent of the 690 trained parents in Uganda are<br />

now aware of their sons’ and daughters’ academic progress. Thanks to the<br />

program, now teachers, committee members and parents are working together<br />

to hold their schools accountable and to motivate their children to succeed.<br />

With more resources and support, East African schools can begin the<br />

transition to a supportive and fulfilling learning environment.<br />

To encourage a reading culture, the East<br />

Africa Quality in Early Learning Program<br />

has set up community libraries where parents<br />

and community members regularly<br />

meet to play learning games with children,<br />

learn how to read and sign out books.

y e a r i n r e v i e w : e d u c a t i o n<br />

<strong>Education</strong> for Marginalized Children in Kenya<br />

PROBLEM: Marginalized Children Need Greater <strong>Education</strong>al Support<br />

The introduction of free primary education by the Government of Kenya has<br />

significantly increased access to primary schooling. Enrollment expanded<br />

from 5.9 million pupils in 2002 to 8.6 million in 2009. However, many<br />

challenges persist, particularly around ensuring quality learning opportunities.<br />

Insufficient resources and preparation at the school level have also meant that<br />

this increase continues to overwhelm the system, causing a concern that<br />

traditionally marginalized groups face a greater risk of being underserved,<br />

especially in Nairobi, Coast and North Eastern provinces. As a result, children<br />

are missing a vital opportunity to grow, learn and prepare for the future.<br />

SOLUTION: <strong>Education</strong> for Marginalized Children in Kenya<br />

AKF is expanding its Whole School Approach<br />

to improve learning and teaching among marginalized<br />

children living in the slums of<br />

Nairobi and Mombasa and other poor regions<br />

of Kenya.<br />

<strong>Education</strong> for Marginalized Children in Kenya (EMACK) is a holistic program<br />

aimed at improving access and retention rates for children underserved by<br />

the education system. Building upon a number of strategies and AKF’s<br />

successful Whole School Approach, EMACK works to increase community<br />

and parental participation in all aspects of school life. It enhances<br />

coordination and dialogue to inform the national education strategy and<br />

improves teaching practices and learner outcomes at the early childhood,<br />

primary and secondary school levels. The program is active in Nairobi, Coast<br />

and North Eastern provinces, where activities have been tailored to reflect<br />

the local education needs as well as the experience of AKF.<br />

The approaches incorporated into EMACK include: (1) A student-centered<br />

focus with attention to quality, purpose and relevance. This requires an explicit<br />

emphasis on promoting self-esteem, enthusiasm for learning and problemsolving.<br />

(2) Working to influence all levels of the system – family, community,<br />

local and traditional institutions, civil society, district-level government services<br />

and national policymakers. (3) Building long-term partnerships – a central<br />

feature for effective programming, sustainability and scaling-up – with local<br />

NGOs, communities and government agencies. (4) Action learning and<br />

documentation to both strengthen services and enhance advocacy.

y e a r i n r e v i e w : e d u c a t i o n<br />

AKF collaborates with a range of locally based partners, the Ministry of<br />

<strong>Education</strong> in Kenya and the US Agency for International Development<br />

(USAID). With generous funding from USAID, AKF will continue to strengthen<br />

the program’s effectiveness by 2014 to reach nearly 800 schools; train over<br />

4,000 teachers, parents and education officials; benefit 275,000 students;<br />

and build the capacity of the Ministry of <strong>Education</strong> to replicate EMACK’s best<br />

practices nationwide.<br />

<strong>Education</strong> for Marginalized Children in<br />

Kenya supports 77 integrated early childhood<br />

development centers in the Coast and<br />

North Eastern Provinces of Kenya in partnership<br />

with AKF’s Madrasa Resource Center,<br />

Kenya.

y e a r i n r e v i e w : e d u c a t i o n<br />

Tranforming the Agrarian School in Mozambique<br />

PROBLEM: Outdated Curriculum Leads to Inefficient Farming<br />

In partnership with the Ford Foundation,<br />

AKF is providing training, technical assistance<br />

and scholarship funds to transform the<br />

Agrarian School of Bilibiza in Mozambique<br />

into an educational institution of excellence.<br />

Cabo Delgado, the northernmost province in Mozambique has the highest<br />

poverty rate in the country. But slowly the area is beginning to grow. Tourism<br />

in the area is becoming more popular, and the fertile land is a good<br />

environment for the region’s dominant economic activity – agriculture. In rural<br />

areas, 95 percent of the households are involved in agricultural production.<br />

Unfortunately, the Escola Agraria de Bilibiza (EAB) – the only agricultural<br />

school in Cabo Delgado – has not kept pace. Cabo Delgado is developing<br />

faster than its communities’ education, and as a result, communities are not<br />

able to capitalize on new economic opportunities.

y e a r i n r e v i e w : e d u c a t i o n<br />

The school's curriculum is in dire need of updating. The basic-level vocational<br />

education currently leaves graduates unprepared and unmotivated to work in<br />

agriculture. Many pursue other careers, and those who fail resort to outmoded<br />

agricultural techniques that lead to poor yields and high vulnerability to floods,<br />

droughts, insect plagues and animal attacks. Inexperienced school<br />

management causes further complications that EAB must address. The<br />

greatest concern, however, continues to be the curriculum’s incongruity with<br />

the development priorities of the province.<br />

SOLUTION: Upgrading the Agrarian School of Bilibiza in Mozambique<br />

In February 2009, the Ford Foundation awarded a grant for AKF to provide<br />

training, technical assistance and scholarship funds to transform the Agrarian<br />

School of Bilibiza into an educational institution of excellence. As the only<br />

agricultural institute in Cabo Delgado, EAB has the potential to play a key<br />

role in the development of the region. AKF has helped introduce a more<br />

advanced curriculum in the school, which will complement educational<br />

changes being made by the government. Teachers have been trained to<br />

conduct entrepreneurship courses alongside teaching agricultural techniques.<br />

This provides students with the tools to think critically and analytically about<br />

the best methods of growing and marketing their crops. In addition, 100<br />

students from poor families received scholarships to attend the school.<br />

As the program advances, all graduates of EAB will leave with knowledge of<br />

modern farming techniques as well as entrepreneurial skills. Those welltrained<br />

students will then, in turn, contribute to their community by running<br />

profitable and successful agricultural businesses. The project plans to improve<br />

school facilities and help increase EAB’s self-sustainability. Plans for a goat<br />

breeding program, an aviary and additional farms are already underway,<br />

which will generate critical income for the school’s upkeep and maintenance.<br />

With an upgraded curriculum, the Agrarian<br />

School of Bilibiza – the only agricultural<br />

school in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique – has<br />

potential to play a key role in development<br />

in the region.

y e a r i n r e v i e w : e d u c a t i o n<br />

Educating Girls in Afghanistan<br />

PROBLEM: Gender Disparities in Afghanistan Leave Girls Uneducated<br />

Educating women and girls is the most important investment a nation can<br />

make, but in countries like Afghanistan, many girls do not make it through<br />

even four years of school. Afghanistan’s education system struggles with a<br />

host of obstacles. The war-torn country is still suffering from crumbling and<br />

destroyed school facilities, few trained teachers and weak school support<br />

systems. In primary schools, on average, there is only one teacher for every<br />

65 students (UNICEF). Although education is compulsory for nine years, 25<br />

percent of boys and only 5 percent of girls attend secondary school.<br />

SOLUTION: Partnership for Advancing Community <strong>Education</strong> in Afghanistan<br />

AKF USA is working in Afghanistan with<br />

CARE, Catholic Relief Services and the International<br />

Rescue Committee to expand access<br />

to quality education especially for girls.<br />

Supported by a grant from the US Agency<br />

for International Development, the Partnership<br />

for Advancing Community <strong>Education</strong> in<br />

Afghanistan has enrolled 95,000 students<br />

in community schools, of which 68 percent<br />

are girls.<br />

The Partnership for Advancing Community <strong>Education</strong> in Afghanistan (PACE-<br />

A) is expanding opportunities for girls and boys to get an education by<br />

providing classes closer to home. Many children must stay at home because<br />

classes are too far away. PACE-A is bringing education to them.<br />

Working in over 2,500 communities, the program is improving the quality of<br />

basic education and getting more girls involved in the process. To address<br />

cultural obstacles preventing girls from staying in school, AKF is working with<br />

parents and training more women teachers. Female teachers encourage higher<br />

enrollment levels for girls, as families are more likely to send their girls to<br />

school when they are taught by a woman. Each year, about 15,000 mothers<br />

and community members are enrolled in adult literacy classes, allowing<br />

mothers to reinforce their child’s education at home. The program encourages<br />

mothers to read to their children and help them with their homework. Many<br />

women are now serving on school advisory and support councils as well.<br />

An active example of partnership and collaboration, the Foundation is working<br />

with a variety of partners to accomplish the important aims of PACE-A. In<br />

collaboration with CARE, International Rescue Committee, Catholic Relief<br />

Services, the Academy for <strong>Education</strong>al Development and with funding from<br />

the USAID, tens of thousands of boys and girls in Afghanistan are now getting<br />

a quality education and a path to a brighter future. So far, the program has<br />

reached approximately 95,000 students, of which 68 percent are girls, and<br />

3,700 teachers, of which 35 percent are female. The entire community is<br />

directly involved in the education process, helping sustain the program and<br />

nurture the next generation of educated youth.

D e v e l o p m e n t S o l u t i o n s w i t h L a s t i n g I m p a c t<br />

As part of our annual report, Aga Khan Foundation U.S.A. is introducing the<br />

first in a series of scholarly articles that examine innovative development<br />

practices and their lasting impact on communities in need. Each year we will<br />

aim to highlight important trends and solutions at the forefront of the<br />

development field. Our goal is to contribute to the ongoing dialogue by sharing<br />

the results of our experience and analyzing the impact of our programs.<br />

In these articles, leading practitioners and scholars reflect on our work at Aga<br />

Khan Foundation from a global development perspective, giving context to<br />

our programs and progress. By framing our work within the broader picture,<br />

we hope to provide our readers with insight into policy implications, spark<br />

interest in development and stimulate ideas for alternative solutions.<br />

In conjunction with our theme, “<strong>Education</strong> – The Universal Bridge,” the<br />

following two articles address current debates, challenges and issues related<br />

to children’s transition to school. Transition and school readiness are critical<br />

topics for examination given the fact that the highest rate of dropouts and<br />

repetition are in Grade 1 in many countries where the Foundation works. A<br />

growing number of the AKF’s education programs and research studies now<br />

focus on the issue of early transitions – not only as it relates to expanding the<br />

range of early childhood supports to children and families but also, and<br />

critically, to improve the quality of learning in early primary classrooms. For<br />

the transition to be smooth, children need to be ready for school and schools<br />

need to be ready for children. Transition is closely linked with another of AKF’s<br />

cross-cutting themes – the work with marginalized or excluded groups. It is<br />

precisely these children that are most at risk during the key transitions in the<br />

education system.

Home to School and Preschool<br />

to School Transitions 1<br />

ROBERT MYERS, PH.D.<br />

Founder and Consultant of the Consultative Group on Early Childhood Care for Development,<br />

Independent Researcher and former Board Member of the Comparative and International <strong>Education</strong> Society<br />

For the past 25 years or more, the education program of the<br />

Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) has worked on a set of problems associated<br />

with the transition from the learning environment of the<br />

home to that of the primary school. It has been motivated to do<br />

so by the increasingly accepted understanding that development<br />

and learning during the early years affect intellect, personality and<br />

behavior over the life course. It has been motivated also by the<br />

continuing failure of many children in the Majority World to enter<br />

primary school as well as by the high rates of grade repetition and<br />

drop out among those who do attend. (AKF <strong>2010</strong>, p. 2)<br />

Support by the Foundation to programs of early childhood development<br />

and particularly to preschool education has been a<br />

central and consistent part of its strategy to bridge home-school<br />

gaps and differences. That support has been provided within an<br />

increasingly broad framework that includes attention not only to<br />

the availability and quality of preschool programs, but also to<br />

the effects on the transition to school of family circumstances, of<br />

community contexts and of educational and related policies established<br />

by governments. Particular attention has been given<br />

as well by AKF to the role that primary schools should be expected<br />

to play in achieving a successful transition from home to<br />

school or from preschool to primary school. This school readiness<br />

part of the process has too often been disregarded or<br />

played down (Ibid.).<br />

Before commenting further on AKF’s work in this area, a brief<br />

discussion is in order of why this topic is important, of different<br />

ways in which the home to school transition has been treated<br />

and how this has changed over time.<br />

Early <strong>Education</strong>al Transitions<br />

and Why They are Important<br />

“Transition” according to Webster’s New World Dictionary is “a<br />

passing from one condition, form, state, activity, place, etc. to<br />

another.” In the field of education, the passage that has received<br />

a great deal of attention, particularly in the Minority<br />

World, 2 is that from preschool to primary school. 3 Associated<br />

with this mandated 4 passage, usually, are changes in physical<br />

locations, teachers, friends, educational content, teaching methods,<br />

hours and institutional rules and forms of discipline, to<br />

mention a few of the most obvious. With the shift also come<br />

changes in expectations (of teachers for children, of children and<br />

parents about what they think will be learned) and in “status”<br />

(to enter school is to acquire the title of “student” and to begin a<br />

new phase in life). The change from preschool to school can<br />

signify personal, social and academic development. However, it<br />

can also be associated with a sense of uncertainty, separation,<br />

longing for the past or disorientation. A major concern is that a<br />

“difficult” transition, for whatever reason, can create lasting<br />

problems for students, reflected in low educational performance,<br />

social or emotional problems and, perhaps, repetition and<br />

1<br />

I am indebted to Kathy Bartlett and Caroline Arnold, co-directors of AKF’s education program, for providing me with program documents as well as with<br />

their own writing on this theme. I am also grateful to Sharon Lynn Kagan for sharing content from the soon-to-be published book, Transitions in the Early<br />

Years: Creating a System of Continuity, which brings together in an extensive review and analysis of the latest thinking about transition seen from a number<br />

of perspectives. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of these materials in this article is, however, obviously mine.<br />

2<br />

Minority and Majority World will be used to avoid the idea of “developed” vs. “developing” or “first” vs. “third” worlds. Minority refers to “developed” world.<br />

3<br />

In the Minority World where most of the research and evaluation related to this theme has been carried out, the emphasis now appears to be on the transition<br />

from preschool to kindergarten which used to be considered preschool but now seems to be considered part of school.<br />

4<br />

In Minority World countries, the decision about when to enter preschool and school and the passage through the system in general is controlled by a set of<br />

age-related laws that dictate when passages should occur. Children and parents have little say about the timing of this transition.

school leaving at an early age. It can provoke or reinforce a debilitating<br />

sense of incompetence and failure. A prime question<br />

for both researchers and policy makers has been, “Why do some<br />

children make this transition smoothly and others do not, presumably<br />

with negative effects on their future productivity, well<br />

being and contributions as citizens” Another question is,<br />

“What can we do about it”<br />

Although the emphasis on the perils of moving from preschool to<br />

school and what to do about it characterizes transition concerns<br />

today in the Minority World where most children already attend<br />

preschool, it is the “transition” directly from home to school that<br />

is often the main concern in Majority World countries where the<br />

AKF works, countries in which many children do not have the<br />

chance to attend a preschool before entering primary school.<br />

This is not the place to go into detail about definitional differences.<br />

However, I have put “transition” in quotes because, conceptually,<br />

at least to me, the notion of a transition means not<br />

only moving from one state or condition to another but also, in<br />

the passage, leaving behind the previous condition. This works<br />

for the passing from preschool to school because preschool is<br />

left behind. It does not work so well when talking about the<br />

move from home into school because a child does not leave the<br />

family behind; rather, the movement is back and forth between<br />

two places, each with their own characteristics and demands.<br />

Some have preferred to use the terms “horizontal transition”<br />

(Kagan <strong>2010</strong>) or “border crossing” (Campbell Clark 2000) for<br />

such situations. In these conceptualizations, the emphasis is<br />

placed on relationship(s) among different learning environments<br />

in which a child participates. The question then is not only how<br />

a child adjusts to a new environment (school) and how “continuity”<br />

may be achieved between them so as to facilitate learning in<br />

the new one, but also how the passage may affect development<br />

and learning in the parallel and continuing environment (home,<br />

but perhaps also the community, the child care center, the<br />

church and the media), and how the differential characteristics<br />

of each environment might be drawn upon to best advantage in<br />

each setting, without creating confusion that drags down the development<br />

and learning processes.<br />

The passage from home to school will be emphasized in this article.<br />

In that passage, worries about discontinuities, adjustment<br />

difficulties and effects on learning and life are supposedly magnified<br />

because the differences between home and school settings<br />

are thought to be much greater than differences between preschool<br />

and school environments. Indeed, establishing<br />

preschools is seen as a way of getting closer to school and of<br />

moderating home-school differences, thereby facilitating the<br />

home-to-school transition. A growing literature from the Majority<br />

as well as Minority Worlds suggests that this strategy can<br />

have the desired effects (Kagan <strong>2010</strong>).

Home, Preschool and School<br />

Learning Environments<br />

As suggested above, in most discussions of early educational<br />

transitions, whether from home to school or from preschool to<br />

school, it is assumed that the learning environments characterizing<br />

these settings are different, enough so that a child faces unsettling<br />

discontinuities when these shifts occur. Therefore, a<br />

great deal of thought and action has been directed toward easing<br />

passages by creating greater continuity among settings under<br />

the additional assumption that greater continuity will make<br />

things easier. But what are these differences One rendering, of<br />

only a few of many possible differences among the learning environments,<br />

is set out in Figure 1.<br />

It should be clear to most readers from a quick look at Figure 1<br />

that the brief descriptions presented are stereotyped views of<br />

what happens in homes, preschools and schools. And yet,<br />

these seem to have a familiar ring. For instance, most primary<br />

schools, particularly in the Majority World, continue to be rather<br />

formal, authoritarian places focused on memorizing and transmitting<br />

knowledge about subjects that may or may not be of interest<br />

to large groups of passive students. Children must adjust<br />

to the inflexible rules and curriculum of the school. The language<br />

of instruction is usually the national language, regardless<br />

of what language the students speak at home.<br />

At the same time, common sense tells us that these descriptions<br />

may or may not hold in particular contexts. Less obvious is the<br />

idea that, at least in some contexts and on some dimensions,<br />

the home and school contexts may not vary as much as Figure 1<br />

would have us believe. For instance, in some of the cultures in<br />

which AKF works, parents tend to be formal and even authoritarian<br />

with their children. They probably believe in the rote<br />

learning and memorization that still characterizes the school.<br />

Children should be taught and told what to do in both settings.<br />

The language spoken at home and in the school may be the<br />

same. Accordingly, in at least some characteristics and settings,<br />

the home and the school may feel very much alike.<br />

I stress the real possibility of similarities between home and<br />

school learning environments to suggest that identifying or<br />

achieving continuity between home and school is not an end in<br />

and of itself; indeed, many would argue that if both environments<br />

impose learning, are authoritarian and eschew active<br />

learning, both need to be changed. This argument may be<br />

grounded in research evidence that suggests children learn better<br />

if they explore, are motivated, etc. Or, it might be based in a<br />

value position stemming, for example, from the Convention on<br />

the Rights of the Child which states that children should be seen<br />

as subjects, not objects; they deserve to be active participants in<br />

their learning. In brief, there is a value dimension to thinking<br />

about transitions that suggests there are better and worse ways<br />

Figure 1<br />

Learning Environments:<br />

The Home, Early Childhood Programs and the School<br />

Home Preschool School<br />

An informal, loving adult-child relationship<br />

Learning through imitation, experience and<br />

trial and error<br />

Contextualized learning<br />

An informal, supportive adult-child relationship<br />

Learning through play and discovery<br />

A mix of contextualized and decontextualized<br />

learning<br />

A formal, less personal adult-child relationship<br />

Learning through didactic teaching, memorization<br />

Decontextualized learning<br />

Modeling, one-on-one teaching Numerous children to one adult Many children to one adult<br />

Adjustments to the interests and needs of<br />

the child<br />

Adjustments to interests and needs of the<br />

child, in the context of the group<br />

Adjustment of the child to the demands of<br />

the school<br />

Emphasis on the concrete Use of concrete/objects to teach concepts Use of symbols<br />

Active participation in chores and rituals Activity-based learning Passive role in learning and school events<br />

Learning in the mother tongue<br />

Learning in the mother tongue, perhaps with<br />

the introduction of a national language<br />

Learning in the national language<br />

Emphasis on process Emphasis on process Emphasis on results

to educate, independent of how similar or different home and<br />

school may be. There are as well cross-cutting issues that have<br />

to do with equity, quality, respect for diversity and with particular<br />

social values and virtues (e.g., valuing autonomy over solidarity)<br />

that felt learning environments should reflect and<br />

promote.<br />

In some characteristics set out in Figure 1, however, there are<br />

clear differences between home and school. Homes have a<br />

much better adult to child ratio for instance. That may or may<br />

not make them better learning environments. 5 At the same<br />

time, we know that very large classes in schools rarely lead to<br />

good results. Class size and the child/teacher ratio are variables<br />

that educational systems can, in theory, control. In theory, transitions<br />

would be aided if class sizes and ratios were reduced.<br />

But another variable enters: available resources. One sees<br />

quickly how complex issues of transition become and how they<br />

move well beyond pedagogy to structural features of institutions,<br />

to policy and to finances (Kagan <strong>2010</strong>).<br />

Changes in Approaches to Transition<br />

Research with Implications for Action<br />

There have been some major shifts in the way transitions from<br />

home and preschool to school have been thought about and acted<br />

upon over the last 25 years. AKF programs have experimented<br />

with and lead some of these shifts which are still seen as part of a<br />

“work in progress.” Among the changes are the following:<br />

1. From developmental psychology focused on the child to an<br />

interdisciplinary view. At an early stage, transition work<br />

asked whether or not children were mature enough or developmentally<br />

“ready” to make the shift into primary school. A<br />

psychological or developmental approach looked hard at<br />

how the pedagogies of preschool and primary school might<br />

be brought closer together to ease the transition. The press<br />

for pedagogical articulation bothered many preschool teachers<br />

and advocates who expressed their concern about moving<br />

the formal didactic orientation of schools downward into<br />

preschools instead of moving active learning upward into<br />

5<br />

Although the ratio may be much more favorable in the home, adults at home have demands on their time that have little to do directly with a child’s development<br />

and learning; whereas, that is the full-time task assigned to teachers.

the early years of primary school. With notable exceptions<br />

in the Minority World (Sweden, for example) that does seem<br />

to have occurred (kindergarten is now part of school). The<br />

position within AKF has been that primary schools should<br />

be much more attuned to active learning methods in the<br />

early years, something made difficult, however, by large<br />

numbers of students and sometimes by cultural traditions<br />

that give little space to exploration and play.<br />

As anthropologists, sociologists, health and nutritional researchers,<br />

political scientists and others have become involved<br />

in the study of transitions, greater attention has been<br />

given to home, community and broader contexts. For instance,<br />

the importance of friends (Corsaro, et al. 2003), absent<br />

fathers, child rearing patterns in the home, health and<br />

nutritional status, community support (Dockett and Perry<br />

2007), etc. began to appear as factors to be taken more directly<br />

into account when considering adjustments to the new<br />

educational environment of the primary school. And, as suggested<br />

above, the broader view of transition also led beyond<br />

pedagogy to analyses of structural limitations within educational<br />

systems as well as the articulation of policies across related<br />

fields. This broader view has begun to take root.<br />

2. From preparing the child and family for school to preparing<br />

the child and family for school AND preparing the school for<br />

the child it will receive. Previously, most if not all emphasis<br />

was placed on getting children ready for school. The main responsibility<br />

for this lay with families but there were things<br />

governments could do to help out including expanding and<br />

improving preschools. Nevertheless, when children failed<br />

during the early years, the tendency of teachers, parents (and<br />

even the children themselves) was to place the blame on the<br />

child. Schools were not at fault and schooling was treated as<br />

given. Accordingly, early education programs became more<br />

and more directed toward correcting that problem, with increasing<br />

emphasis on developing specific cognitive skills<br />

needed in primary schools rather than on integral development.<br />

Indeed, this view continues to dominate thinking.<br />

However, another view has emerged in which all children of a<br />

certain age are considered in some sense “ready” for primary

3. From considering the child as an object to viewing the child<br />

as a subject. The Convention on the Rights of the Child<br />

clearly states the importance of treating children as people<br />

with specific rights. They are people who, even during the<br />

early years, should have the opportunity to offer opinions,<br />

including opinions about how their environment might be<br />

improved, and to be actively involved in their own development<br />

and learning (Lam and Pollard 2006). They should<br />

be listened to. Nevertheless, until recently, most of the research<br />

on transitions was based on information obtained<br />

from adult perceptions of how children adjust to school.<br />

Children were not asked. As a result, some topics of particular<br />

significance to children, such as peer relationships and<br />

bullying, did not necessarily appear as important issues to<br />

be dealt with during the transition.<br />

school, but with levels and kinds of readiness that differ from<br />

child to child and perhaps even group to group. A child may<br />

be healthy and intelligent but is not ready to speak in the national<br />

language. A child may handle the national language<br />

reasonably well but lack certain social skills. Slowly, rather<br />

than think that families and preschools should carry the full<br />

burden for preparing children, more attention is being given to<br />

the idea that primary schools should be more flexible and<br />

should be prepared to change what they do during the early<br />

years in order to be ready for the diverse children they receive.<br />

In writings of the AKF staff and elements of AKF programming,<br />

this way of thinking is reflected. Schools should<br />

be welcoming, inclusive, responsive, offer appropriate and relevant<br />

learning experiences, and know how to work with differences<br />

among the children they receive (Arnold, Bartlett,<br />

Gowani and Shallwani 2008).<br />

Moreover, the Foundation has taken on an important advocacy<br />

role in calling attention to the need to reform and<br />

strengthen the early years of primary school. It has argued<br />

that governments and international organizations tend to give<br />

priority to the later years, failing to provide the resources and<br />

policies necessary to improve the early grades (AKF <strong>2010</strong>).<br />

4. From seeing transition as a moment in time to seeing it as a<br />

continuous process. Much of the transition research and<br />

many of the actions suggested as most pertinent for resolving<br />

transition problems have focused on the moment of<br />

transition to the school or perhaps a brief period before and<br />

another just after making the passage. Children and families<br />

were provided with visits and orientations to the school.<br />

Administrative procedures were introduced to make sure<br />

children’s records from preschool followed them into the primary.<br />

Occasionally, older children were assigned to younger<br />

ones to make sure they had someone to help then navigate<br />

the new environment. The first few days or weeks of school<br />

was sometimes made to feel much more like a continuation<br />

of preschool.<br />

Again, the view has broadened. The passage into school is<br />

now recognized as something that is affected by what happens<br />

long before the actual move occurs and continues well<br />

into the primary school years (Love and Raikes 2007). It is<br />

part of a continuous educational passage in which children<br />

change teachers and curricula and spaces each year in the<br />

school. It is part of a longer-term process of working with<br />

parents and communities.<br />

All of these shifts in thinking and action have involved moves toward<br />

more sophisticated and complicated ways of considering the<br />

passage from home and preschool to school. Keeping this broad<br />

view in mind, let me turn now to discuss what has been done and<br />

what might be done to help children as they shift among learning<br />

environments.

greater continuity among them vs. providing “compensatory” programs<br />

that do little to change either environment but try to provide<br />

children with additional tools to function in primary schools.<br />

When the differences between or among learning environments<br />

are huge, as is often the case in the Majority World, actions that<br />

seek to create greater continuity probably need to be accompanied<br />

by what are often called “compensatory” actions. For instance, if<br />

a child is malnourished or has a very limited vocabulary it may be<br />

necessary to create special programs directed toward these particular<br />

shortcomings. However, if nothing is done in the meantime<br />

to change the environments that produce the shortcomings, the<br />

problem will continue over time.<br />

How Can the “Transition” from<br />

Home to School be Facilitated<br />

The main answer to this question has been, and probably will<br />

continue to be, by (1) providing the child with a solid and integral<br />

developmental base to take forward into (2) quality primary<br />

schools that are welcoming, inclusive and responsive, that offer<br />

appropriate integral and relevant learning experiences, and know<br />

how to work with differences among the children they receive.<br />

The solid developmental base may be provided at home but<br />

more often will require (3) complementary attention to children<br />

in quality Early Childhood <strong>Education</strong> and other programs that<br />

complement or compensate for unfavorable conditions in home<br />

environments. Along the way, at both preschool and school levels,<br />

important efforts are needed to (4) build on and enhance<br />

strengths in home learning environments and activities of parents<br />

that will enrich the developmental base and support formal<br />

educational programs. All of this should be set within a context<br />

of supportive communities and policy frameworks. But all of<br />

this is easier said than done in the real world.<br />

As the definition of the problem and the way to approach it has<br />

broadened, the variety of actions that have been carried out has<br />

broadened as well. There are several ways in which these might<br />

be classified. One of these is in terms of actions that focus on<br />

changes in the respective environments that help to provide<br />

Another classification of actions to improve transitions might be<br />

according to the emphasis actions put on particular actors (children,<br />

parents, communities, preschools, primary schools, educational<br />

systems, policy makers). Who/what is expected to change<br />

For instance, in the most common focus on children, a wide variety<br />

of interventions affecting their health, nutritional and cognitive<br />

developmental status have been put in place to make them<br />

“ready” for school (see below). However, within each of these categories<br />

it is possible to identify many actions that have been tried<br />

out (orientation sessions for parents, curriculum changes in the<br />

first months of primary school, reducing child/teacher ratios in first<br />

grade, etc.). Again, it is clear that combinations of these will be<br />

more effective than actions focused on a single actor.<br />

Kagan (<strong>2010</strong>) has suggested a new typology of pedagogical,<br />

programmatic and policy actions that are needed, emphasizing<br />

the need to incorporate much more forcefully and centrally the<br />

world of policy.<br />

In this article, rather than elaborate or use any of these I prefer<br />

to discuss three basic strategies that seem to have characterized<br />

work on transitions.<br />

Strategies for Facilitating Home<br />

to School Transitions 6<br />

1. Change the child and the home. Here the problem is seen<br />

as one of deficiencies in the child and in the home that leave<br />

the child poorly prepared for school. 7 This is the most fre-<br />

6<br />

This section draws on Myers 1997.<br />

7<br />

To be prepared, a child should be: physically healthy and well nourished; able to handle basic cognitive concepts; able to communicate in everyday transactions<br />

and in the language of school; able to relate to others; psychologically self-assured with a good self concept; able to work independently; and motivated<br />

to learn.

quent approach to improving transitions and includes a wide<br />

variety of early childhood interventions (preschools among<br />

them) originating mainly in education, health and social welfare<br />

programs. In its early years of programming, AKF focused<br />

heavily on this strategy, with programs to provide<br />

children with a preschool experience. It has done so using a<br />

holistic approach placing emphasis on recognizing, respecting<br />

and building on strengths as well as on addressing issues in<br />

the broader context which can put a brake on young children’s<br />

development. Evaluations by AKF of these programs<br />

leave little doubt that these have been effective (p.e.,<br />

Mwaura, Sylva and Malmberg 2008; AKF 2009).<br />

Despite its proven effectiveness in many places, this approach<br />

must be viewed as partial and with some related<br />

cautions such as:<br />

a. Implicitly or explicitly the blame for failure in school is<br />

on the child or family, potentially contributing to the<br />

culture of failure.<br />

b. The strategy may bring with it intended or unintended<br />

devaluing of popular or minority cultures. The crosscutting<br />

consideration of respect for diversity comes<br />

into play.<br />

c. The strategy begins by identifying “deficits” and focuses<br />

on how to “compensate” for them rather than<br />

accentuate strengths.<br />

Better preparing children for school may involve less attention<br />

to skills and abilities crucial to everyday living. Sometimes<br />

an integrated view of child development is lost in<br />

order to enhance cognitive development.<br />

Limits on the effectiveness of these programs may be related<br />

also to the poor quality of programs offered (another of<br />

the cross-cutting themes). Moreover, particularly large gaps<br />

between what children bring to school and what schools expect<br />

from them may make filling those gaps impossible before<br />

arrival at school. In many settings these are related to<br />

poverty, suggesting the need to place them in a broader policy<br />

context reaching well beyond education.<br />

2. Changing the school. As mentioned earlier, in recent years<br />

more attention has been given to changing the school to be<br />

more receptive to incoming students. This is happening in<br />

a variety of ways that include:<br />

a. Adding special programs within the primary school to<br />

help children. These might be special courses given<br />

just before children enter but run by the primary<br />

schools, arranging tutorials for students who need<br />

them and strengthening health and nutritional elements<br />

in programs.<br />

b. Changing the curriculum and pedagogical practices.<br />

Some schools have created a special period during the<br />

first months of the first year of primary in which the<br />

curriculum is more exploratory and play-based. This<br />

does not necessarily mean a new commitment to a<br />

new way of teaching but, rather, is intended to provide<br />

a space for adjustment on arrival.<br />

c. Change the teacher. Sylva and Blatchford (1994) suggest<br />

several strategies to improve teaching in the early<br />

grades. First, train teachers differently for lower and<br />

upper primary grades. Second, place the most able<br />

and highly qualified teachers in the lower grades. This<br />

may require introducing special incentives. Third, include<br />

in teacher training guidance on young children’s<br />

learning needs, language and bi-lingual development<br />

as well as on appropriate active learning pedagogy.<br />

Fourth, develop career structures for teachers to increase<br />

motivation and commitment and provide ongoing<br />

training. (Unfortunately, much of the present<br />

on-the-job training occurs through short courses and<br />

with no follow-up so teachers do not change their<br />

classroom behavior.)<br />

d. Change the administration, organization and rules. Perhaps<br />

reductions in the number of children per teacher<br />

fall into this category. In another vein, New Zealand has<br />

experimented with entrance on an individual basis when<br />

a child turns five, regardless of when that occurs during<br />

the year. The argument is that this assures more individual<br />

attention to children.<br />

Often the histories of school systems, entrenched structural<br />

problems and resource constraints, perceived or real, make<br />

it difficult to carry out these kinds of changes.<br />

3. Seeking smoother transitions by building linkages: education<br />

as a shared experience. This third approach stresses<br />

strengthening the relationships among diverse people and institutions<br />

that influence a child’s early development. This<br />

strategy will include actions that seek to smooth the transition

y making a child’s various environments look more alike. In<br />

looking at the move from preschool to school, for instance, it<br />

might involve: providing greater continuity in the curricula of<br />

the two, a common core curriculum in teacher training institutions<br />

for preschool and primary school teachers for some<br />

period of their training, allowing a teacher to move with<br />

her/his students as they make the passage from preschool to<br />

the first year or two of primary, and building collaborative relationships<br />

between preschool and primary teachers through<br />

regular meetings, joint ongoing training.<br />

To help home and school relate the usual approach is to work to<br />

“educate” parents so they will change the home learning environment.<br />

What this strategy seldom takes into account is that<br />

parents have positive practices that can be reinforced, some of<br />

which teach children entirely different things than they will learn<br />

in school. The strategy seldom sees parents as resources for the<br />

school beyond their providing funds or helping with maintenance.<br />

Parents are often kept at the door and not allowed to<br />

become involved in the school, something that can increase the<br />

understanding and communication for both parties.<br />

If one thinks of relationships between health or social welfare<br />

systems and the school, another set of actions to strengthen<br />

common cause is required.<br />

Perhaps the essential point associated with this strategy is that,<br />

even while making some helpful adjustments in the home or the<br />

school that may “smooth the transition,” it is also valuable to: (1)<br />

find ways to respect the unique and positive points of each environment;<br />

(2) anticipate and provide orientation for changes that will<br />

be faced by children and parents; and (3) develop broad coping<br />

skills in children (rather than try to mold them to one environment<br />

or another); foster continuing communication among the adults in<br />

the child’s life; and find means of supporting each child in his or<br />

her particular passages (Myers 2007).<br />

In Closing<br />

In closing, I would like to emphasize that Aga Khan Foundation,<br />

together with the Bernard van Leer Foundation, UNICEF and other<br />

organizations associated with the Consultative Group on Early<br />

Childhood Care and Development, has taken on an extremely important<br />

role in calling attention to the importance of working on<br />

transition to primary school in the Majority World over the past 25<br />

years. As indicated earlier, most of the work on this topic and<br />

most of the publicity given to it has been carried out in the Minority<br />

World until very recently. AKF has called attention to the topic<br />

by example, supporting specific programs in a variety of countries.<br />

These programs have not only benefited the local populations but<br />

have fed into an international literature as the results of evaluations<br />

have been published (e.g., Mwara 2008; Institute for Professional<br />

Development 2008; AKF 2009). It has called attention by<br />

carrying out research reviews and sharing the results (AKF <strong>2010</strong>).<br />

It has participated in both academic meetings (e.g., Bartlett and<br />