View - Coccidia.icb.usp.br - USP

View - Coccidia.icb.usp.br - USP

View - Coccidia.icb.usp.br - USP

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

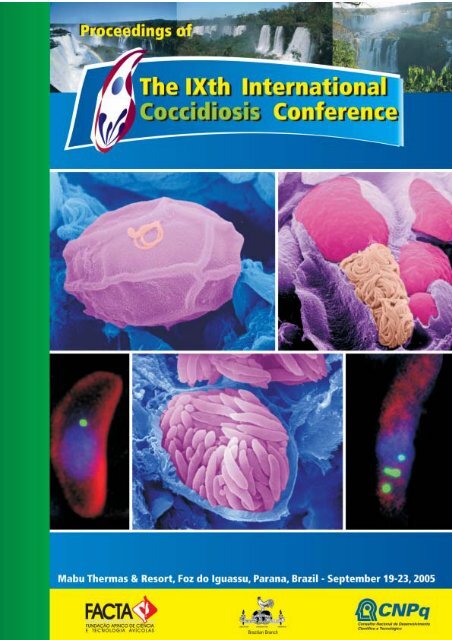

Front cover figure legends:<<strong>br</strong> />

A. Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of an oocyst in the gut lumen showing partial loss of the veil and<<strong>br</strong> />

with a microgamete adhering to the outer layer of the oocyst wall.<<strong>br</strong> />

B. SEM of a fracture through a caecum infected with E. tenella showing a microgametocyte with<<strong>br</strong> />

numerous mature microgametes in a cell adjacent to a macrogamete.<<strong>br</strong> />

C and E. Tachyzoite of T. gondii (C) and merozoite of E. tenella (E) and labelled with anti-enoyl reductase<<strong>br</strong> />

showing the peri-nuclear location of the single or multiple apicoplasts (green). .<<strong>br</strong> />

D. SEM of a mature schizont of Eimeria tenella showing the individual merozoites.<<strong>br</strong> />

The original images were kindly supplied by Dr. David J. P. Ferguson (Oxford University, UK), copied and<<strong>br</strong> />

printed with permission. Copyright is retained by the author.

Proceedings of<<strong>br</strong> />

The IX th International<<strong>br</strong> />

Coccidiosis Conference<<strong>br</strong> />

Foz de Iguassu, Parana, Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

September 19-23, 2005

FACTA - APINCO Foundation of Poultry Science and Technology<<strong>br</strong> />

WPSA-Brazilian Branch<<strong>br</strong> />

Av. Andrade Neves, 2501 - Castelo - Campinas - SP - Brazil - 13070-001<<strong>br</strong> />

Tel: +55 19 3243-6555 • Fax: +55 19 3243-8542 • facta@facta.org.<strong>br</strong><<strong>br</strong> />

Site: http://www.facta.org.<strong>br</strong><<strong>br</strong> />

PUBLISHING STAFF<<strong>br</strong> />

Coordination: Arthur Gruber/Ariel Antonio Mendes<<strong>br</strong> />

Organization: Nilza S. Marcondes/Glaucia C. de Campos Faria/Carla R. Palermo<<strong>br</strong> />

Proof-reading: Bettina Gertum Becker<<strong>br</strong> />

Graphic creation, edition, and production: AGROS Comunicação – 55 19 3241-9292<<strong>br</strong> />

Secretariat/Registration: Nilza S. Marcondes/Glaucia C. de Campos Faria/Carla R. Palermo<<strong>br</strong> />

Financial Department: Nilza S. Marcondes

FACTA - APINCO FOUNDATION OF POULTRY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY<<strong>br</strong> />

FACTA COUNCIL<<strong>br</strong> />

José Flávio Neves Mohallem – Granja Planalto Ltda - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Antonio Mário Penz Junior – UFRGS – Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Aroldo Silva Amorim Filho – Asa Alimentos Ltda - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Edir Nepomuceno da Silva – Unicamp - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Élsio Antônio Pereira de Figueiredo – Em<strong>br</strong>apa - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Fernando Bacci – Granja São José Ltda - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Ivan Pupo Lauandos – Agroceres - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

José Carlos Godoy – APINCO - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Luiz Antonio Bossi – Granja Alvorada Ltda - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Paulo Tabajara Chaves Costa – UFSM - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Pedro Benur Bohrer – Seara Alimentos - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Roberto Kaefer – Globoaves Agroavícola - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Zoé Silveira D´Ávila – UBA - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE<<strong>br</strong> />

Ariel Antonio Mendes – President<<strong>br</strong> />

Antonio Guilherme Machado de Castro – Marketing Director<<strong>br</strong> />

Edir Nepomuceno da Silva – Events Director<<strong>br</strong> />

Irenilza de Alencar Naas – Especial Projects Director<<strong>br</strong> />

José Di Fábio – Financial Director<<strong>br</strong> />

Luiz Almiro Carvalho Sesti – Executive Director<<strong>br</strong> />

Marcos Macari – Courses and Publishing Director<<strong>br</strong> />

TECHNICAL COMMITTEE<<strong>br</strong> />

Alberto Bernardino - Fort-Dodge Saúde Animal - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Antonio Mário Penz Junior – UFRGS – Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Antonio Guilherme Machado de Castro – Instituto Biológico - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Ariel Antonio Mendes – Unesp - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Byron Grieco Moreira da Silva – Intervet - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Diogo Tsuyoshi Ito – Nutron - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Élsio Antônio Pereira de Figueiredo – Em<strong>br</strong>apa - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Edir Nepomuceno da Silva – Unicamp - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Fabio Tavares Zancan – PUC – Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Ga<strong>br</strong>iel Jorge Neto – Nutron - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Godofredo Miltenburg – Delta Assessoria - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Inaldo Sales Patrício – Consultor - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Irenilza de Alencar Naas - Unicamp - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

João Batista Luchesi – Multimix - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

João Tomelin – UBA - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

José Di Fábio – JF Laboratório - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Luiz Almiro Carvalho Sesti - Multimix - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Marcelo A. Fagnani Zuanaze – Biovet - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Marcos Macari - Unesp - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Nelson José Beraquet – Ital - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Paulo César Martins – Euri<strong>br</strong>id - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Tércio Michelan Filho – Agroceres - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Teresa Cristina Ruocco Dari – Nutron - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

ADMINISTRATION COMMITTEE<<strong>br</strong> />

Nilza Santos Marcondes – Financial Executive<<strong>br</strong> />

Glaucia C. de Campos Faria – Convention Organizer<<strong>br</strong> />

Carla Rizzo Palermo – Communication Assistant<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference € 5

IX TH INTERNATIONAL COCCIDIOSIS CONFERENCE<<strong>br</strong> />

General Organizer<<strong>br</strong> />

Arthur Gruber - Universidade de São Paulo (<strong>USP</strong>) - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

International Scientific Committee<<strong>br</strong> />

David Chapman<<strong>br</strong> />

Fiona Tomley<<strong>br</strong> />

Hyun S. Lillehoj<<strong>br</strong> />

Kazumi Sasai<<strong>br</strong> />

Mark Jenkins<<strong>br</strong> />

Martin W. Shirley<<strong>br</strong> />

Nick Smith<<strong>br</strong> />

University of Arkansas – USA<<strong>br</strong> />

Institute for Animal Health – UK<<strong>br</strong> />

US Department of Agriculture – USA<<strong>br</strong> />

Osaka Prefecture University - Japan<<strong>br</strong> />

US Department of Agriculture – USA<<strong>br</strong> />

Institute for Animal Health – UK<<strong>br</strong> />

University of Technology Sydney – Australia<<strong>br</strong> />

Organizing Committee<<strong>br</strong> />

Alda Maria B. N. Madeira<<strong>br</strong> />

Arthur Gruber<<strong>br</strong> />

Rosângela Zacarias Machado<<strong>br</strong> />

Solange Maria Gennari<<strong>br</strong> />

Ariel Antonio Mendes<<strong>br</strong> />

Byron Grieco Moreira da Silva<<strong>br</strong> />

Carlos O. Cardoso Pulici<<strong>br</strong> />

Clóvis de Oliveira<<strong>br</strong> />

Dieter Suída<<strong>br</strong> />

Eduardo Villas Boas Leffer<<strong>br</strong> />

Fernando José Bertazzo<<strong>br</strong> />

José Di Fabio<<strong>br</strong> />

Luiz Adolfo Bier Neto<<strong>br</strong> />

Marcel Louis Joineau<<strong>br</strong> />

Marcelo A. Fagnani Zuanaze<<strong>br</strong> />

Marco Antonio C. de Almeida<<strong>br</strong> />

Maurício Luiz do Nascimento<<strong>br</strong> />

Paulo José Ubices de Moraes<<strong>br</strong> />

Rogério B. Petri<<strong>br</strong> />

Universidade de São Paulo (<strong>USP</strong>) - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Universidade de São Paulo (<strong>USP</strong>) - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Universidade do Estado de São Paulo (UNESP) - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Universidade de São Paulo (<strong>USP</strong>) - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

FACTA – Fundação APINCO de Ciência e Tecnologia Avícolas - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Azko Nobel Ltda – Div. Intervet - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Imuvet Comercial Ltda - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Merial Saúde Animal Ltda - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Novus do Brasil Comércio e Importação Ltda - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Schering Plough - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Eli Lilly do Brasil Ltda - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

JF Laboratório - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Inovoject do Brasil - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Impextraco - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Laboratório Biovet S.A. - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Alpharma Animal Health - Divisão Brasil - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Phi<strong>br</strong>o Animal Health - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Laboratórios Pfizer Ltda - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Bayer do Brasil S/A - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Secretariat<<strong>br</strong> />

Carla Rizzo Palermo – FACTA - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Glaucia C. de Campos Faria – FACTA - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Nilza Santos Marcondes – FACTA - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference • 7

Sponsors<<strong>br</strong> />

The organizers of the IXth International Coccidiosis Conference acknowledge the following companies<<strong>br</strong> />

for their financial support and generosity:<<strong>br</strong> />

• Akzo Nobel – Intervet Division<<strong>br</strong> />

• Alpharma Inc.<<strong>br</strong> />

• Em<strong>br</strong>ex Inc.<<strong>br</strong> />

• Imuvet Comercial Ltda.<<strong>br</strong> />

• Janssen Animal Health<<strong>br</strong> />

• Laboratório BioVet S/A<<strong>br</strong> />

• Laboratorios Inmuner<<strong>br</strong> />

• Laboratórios Pfizer Ltda<<strong>br</strong> />

• Merial Saúde Animal Ltda<<strong>br</strong> />

• Novartis Animal Health<<strong>br</strong> />

• Novus International Inc.<<strong>br</strong> />

• Phi<strong>br</strong>o Animal Health<<strong>br</strong> />

• Schering-Plough<<strong>br</strong> />

• Vetech Laboratories Inc.<<strong>br</strong> />

Support<<strong>br</strong> />

CNPq – Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (National Research Council) - Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference • 9

Introduction<<strong>br</strong> />

It is a great honor to host the IX th International Coccidiosis Conference (IX th ICC) and welcome the<<strong>br</strong> />

delegates at the Mabu Thermas & Resort, in the city of Foz do Iguassu, Brazil. At its ninth edition, and<<strong>br</strong> />

being held each four years, since 1973, the Conference has become the most traditional meeting in<<strong>br</strong> />

coccidiosis research. This meeting has aggregated academic and private company researchers, product<<strong>br</strong> />

managers, and field professionals, providing an opportunity for information interchange of both basic and<<strong>br</strong> />

applied sciences.<<strong>br</strong> />

We have decided to hold the IXth ICC in the city of Foz do Iguassu. World widely known for its famous<<strong>br</strong> />

Iguassu Falls, Foz do Iguassu represents Brazil’s one of the most important touristic sites. A wonderful<<strong>br</strong> />

nature, including two National Parks, in Brazilian and Argentinean sides, ecological tours, and a very<<strong>br</strong> />

diverse wild life, composes a rich scenario for this meeting. We hope all delegates enjoy the conference<<strong>br</strong> />

and also have a pleasant stay in this natural paradise.<<strong>br</strong> />

In this ninth edition of the Conference, we tried to maintain the spirit that has characterized the former<<strong>br</strong> />

events. Traditional approaches for coccidiosis control and diagnosis will be presented side-by-side with<<strong>br</strong> />

highly innovative technologies. We received contributed papers of many different topics, including vaccines,<<strong>br</strong> />

chemotherapy, basic immunology, molecular and cell biology, pathology, genomics and post-genomics.<<strong>br</strong> />

Taking into account the increasing importance of vaccines in coccidiosis control, we have prepared specific<<strong>br</strong> />

sessions to discuss new approaches and technologies for vaccination. We have also invited a group of<<strong>br</strong> />

selected academic researchers for the plenary lectures, to present the state-of-art of research and<<strong>br</strong> />

development. A new age has arisen since large scale genome sequencing became a mainstream approach<<strong>br</strong> />

to unravel the complexity of living organisms. For the first time in history, we now have access to the<<strong>br</strong> />

complete genome information of some coccidian parasites like Toxoplasma gondii, Eimeria tenella and<<strong>br</strong> />

two species of Cryptosporidium. Where is this information going to lead us How will it contribute for new<<strong>br</strong> />

control measures This is an issue that will also be discussed and, we hope, will open up new trends for<<strong>br</strong> />

the disease control. Finally, the increasing importance of new regulations on the use of anticoccidial<<strong>br</strong> />

drugs and vaccines stimulated us to include a symposium on current and future perspectives of legislation.<<strong>br</strong> />

This symposium will be followed by an organized public debate, where the major trends of this important<<strong>br</strong> />

issue will be openly discussed.<<strong>br</strong> />

Social activities were also programmed to complement the scientific programme, allowing for delegates<<strong>br</strong> />

to know each other and create an environment of professional and personal integration.<<strong>br</strong> />

We wish you a pleasant stay in Foz do Iguassu, and a very fruitful Conference.<<strong>br</strong> />

Arthur Gruber<<strong>br</strong> />

Conference Organizer<<strong>br</strong> />

Ariel Antonio Mendes<<strong>br</strong> />

President of FACTA<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference • 11

Contents<<strong>br</strong> />

Contents<<strong>br</strong> />

Professor Peter L. Long: an Appreciation .................................................................................... 21<<strong>br</strong> />

Martin W. Shirley<<strong>br</strong> />

Plenary Lectures<<strong>br</strong> />

Eight decades of research on Eimeria in poultry ......................................................................... 29<<strong>br</strong> />

Martin W. Shirley - martin.shirley@bbsrc.ac.uk<<strong>br</strong> />

Genome sequence of the avian coccidiosis-causing agent, Eimeria tenella ............................... 36<<strong>br</strong> />

Matt Berriman - mb4@sanger.ac.uk<<strong>br</strong> />

Proteomics of Eimeria : a focus on host cell invasion ................................................................. 37<<strong>br</strong> />

Fiona Tomley - fiona.tomley@bbsrc.ac.uk<<strong>br</strong> />

The role of morphology and microscopy<<strong>br</strong> />

in coccidian research in this genomic/proteomic age ................................................................. 41<<strong>br</strong> />

David J. P. Ferguson - david.ferguson@ndcls.ox.ac.uk<<strong>br</strong> />

New roles for proteases in the infection biology of coccidian parasites ................................... 51<<strong>br</strong> />

Vern B. Carruthers - vcarruth@jhsph.edu<<strong>br</strong> />

Horizontally transferred genes as new<<strong>br</strong> />

targets for drug development in Cryptosporidium parvum ....................................................... 60<<strong>br</strong> />

Boris Striepen - striepen@cb.uga.edu<<strong>br</strong> />

Immune response to <strong>Coccidia</strong> ...................................................................................................... 63<<strong>br</strong> />

Hyun S. Lillehoj - hlilleho@anri.barc.usda.gov<<strong>br</strong> />

Protective immune responses involved in host<<strong>br</strong> />

resistance to Brazilian isolates of Toxoplasma gondii:<<strong>br</strong> />

implications on vaccine development employing recombinant viral vectors ............................ 84<<strong>br</strong> />

Ricardo T. Gazzinelli - ritoga@cpqrr.fiocruz.<strong>br</strong><<strong>br</strong> />

Immune responses to Neospora caninum and prospects for vaccination .................................. 91<<strong>br</strong> />

Elisabeth A. Innes - Lee.Innes@moredun.ac.uk<<strong>br</strong> />

Perspectives for the control of coccidiosis in poultry by chemotherapy and vaccination ........ 99<<strong>br</strong> />

H. David Chapman - dchapman@uark.edu<<strong>br</strong> />

Anticoccidial drug discovery:<<strong>br</strong> />

approaches towards the identification of novel chemotherapeutic agents ............................ 104<<strong>br</strong> />

Paul Liberator - paul_liberator@merck.com<<strong>br</strong> />

Vaccination against coccidial parasites. The method of choice .............................................. 105<<strong>br</strong> />

Arno N. Vermeulen - arno.vermeulen@intervet.com<<strong>br</strong> />

Symposium “Legislation on drug and vaccine use”<<strong>br</strong> />

A US perspective on the current and future regulation of anticoccidial drugs and vaccines.. 117<<strong>br</strong> />

Paul Duquette - Paul.Duquette@pahc.com<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference • 13

Contents<<strong>br</strong> />

Feed Safety: Evolution in Legislation, Implementation and Harmonisation ........................... 126<<strong>br</strong> />

Yvan Dejaegher - dejaegher.yvan@skynet.be<<strong>br</strong> />

Current and futures perspectives on the regulation of anticoccidial drugs and vaccines ....... 128<<strong>br</strong> />

João Palermo Neto - jpalermo@<strong>usp</strong>.<strong>br</strong><<strong>br</strong> />

Symposium “Histomonas meleagridis: Update on Life Cycle, Control and Diagnostics”<<strong>br</strong> />

Histomonas meleagridis: life cycle and epidemiology.............................................................. 131<<strong>br</strong> />

Maarten De Gussem - dgussem@janbe.jnj.com<<strong>br</strong> />

The diagnostics of Histomonas meleagridis .............................................................................. 132<<strong>br</strong> />

Wil Landman - w.landman@gdvdieren.nl<<strong>br</strong> />

Histomoniasis, an ancient disease threatening the European poultry production.<<strong>br</strong> />

What are the current and future options for control .............................................................. 133<<strong>br</strong> />

Koen De Gussem - koen.degussem@alpharma.com<<strong>br</strong> />

Enteric flagellated protozoa in turkeys. ..................................................................................... 134<<strong>br</strong> />

Steven Clark - steven.clark@alpharma.com<<strong>br</strong> />

Contributed Papers: Oral Presentations<<strong>br</strong> />

Vaccines<<strong>br</strong> />

Guidelines for evaluating the efficacy and safety of live<<strong>br</strong> />

anticoccidial vaccines, and obtaining approval for their use in chickens and turkeys<<strong>br</strong> />

H. David Chapman - dchapman@uark.edu ........................................................................................................................... 137<<strong>br</strong> />

Selection of a precocious line of the rabbit coccidium Eimeria piriformis<<strong>br</strong> />

and characterization of the life cycle of both the parent strain and the precocious line<<strong>br</strong> />

Michal Pakandl - pakandi@paru.cas.cz .................................................................................................................................. 137<<strong>br</strong> />

Long Term Viability of Cryopreserved Eimeria Sporocysts<<strong>br</strong> />

Rebecca M. Poston - rposton@em<strong>br</strong>ex.com .......................................................................................................................... 138<<strong>br</strong> />

Non-interference of INOVOCOX , a live coccidial oocyst vaccine, with Marek’s<<strong>br</strong> />

Disease Vaccine or Bursaplex®, A live bursal disease vaccine, after in ovo administration<<strong>br</strong> />

Vivian W. Doelling - vdoeling@em<strong>br</strong>ex.com ............................................................................................................................ 138<<strong>br</strong> />

Uniformity of Infection after INOVOCOX Delivery AT E18 Using the INOVOJECT ® System<<strong>br</strong> />

Rebecca M. Poston - rposton@em<strong>br</strong>ex.com .......................................................................................................................... 139<<strong>br</strong> />

In Ovo and Dietary Modulation of Host Intestinal Immunity<<strong>br</strong> />

and its Subsequent Effects on Coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

Rami A. Dalloul - rdalloul@anri.barc.usda.gov ........................................................................................................................ 139<<strong>br</strong> />

Effects of dietary short chain fatty acids on experimentally induced<<strong>br</strong> />

coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis in <strong>br</strong>oilers vaccinated against coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

Mauro Antongiovanni - mauro.antogiovanni@unifi.it ............................................................................................................. 140<<strong>br</strong> />

The Effect of Light Intensity During Brooding<<strong>br</strong> />

on the Productivity and Health of Paracox-5 Vaccinated Broilers<<strong>br</strong> />

Luciano Gobbi - luciano.gobbi@spcorp.com ........................................................................................................................... 141<<strong>br</strong> />

Efficacy of gel spray as a delivery system for turkey coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

vaccine consisting of Eimeria adenoeides and E. meleagrimites<<strong>br</strong> />

Roberto Soares - rbsoares@vetechinc.com ............................................................................................................................ 141<<strong>br</strong> />

Comparison Of Performance Of Ross Broiler Breeder Males To Full,<<strong>br</strong> />

Half-Dose And 10X Dose Of Coccivac ® -D Day-of-Age Vaccination<<strong>br</strong> />

Stephen W. Davis - steve@coloradoqualityresearch.com ....................................................................................................... 142<<strong>br</strong> />

Safety And Efficacy Of Advent ® Coccidiosis Vaccine<<strong>br</strong> />

Marco A. Quiroz - marco.quiroz@novusint.com ..................................................................................................................... 143<<strong>br</strong> />

Performance of Broilers Using A Live Vaccine Against Avian Coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

Alejandro Juan José Dubois - alejudubois@hotmail.com ......................................................................................................... 144<<strong>br</strong> />

14 • IXth International Coccidiosis Conference

Contents<<strong>br</strong> />

Efficacy of Coccivac against field isolates of chicken Eimeria<<strong>br</strong> />

Steve Fitz-Coy - steve-fitz-coy@spcorp.com .......................................................................................................................... 145<<strong>br</strong> />

Growout Performance Following Vaccination with Inovocox As Compared to Salinomycin<<strong>br</strong> />

Alison Martin - amartin@em<strong>br</strong>ex.com .................................................................................................................................... 145<<strong>br</strong> />

Anticoccidial Sensitivity Profile of <strong>Coccidia</strong>l Strains in Inovocox<<strong>br</strong> />

Alison Martin - amartin@em<strong>br</strong>ex.com .................................................................................................................................... 146<<strong>br</strong> />

Maternal Protection against Eimeria challenge of CoxAbic® vaccinated chickens<<strong>br</strong> />

Amnon Michael - amnon.michael@teva.co.il ......................................................................................................................... 146<<strong>br</strong> />

Use of avian immunoglobulins in the control of coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

Andrea Rodríguez Ropon - arodriguez@grupoidisa.com ........................................................................................................ 147<<strong>br</strong> />

Acquisition of immunity to Eimeria maxima in newly hatched chickens given 100 oocysts<<strong>br</strong> />

H. David Chapman - dchapman@uark.edu ........................................................................................................................... 148<<strong>br</strong> />

Inovocox Onset Of Immunity After in Ovo Delivery to Broilers<<strong>br</strong> />

Vivian W. Doelling - vdoelling@em<strong>br</strong>ex.com ........................................................................................................................... 148<<strong>br</strong> />

Immune reactions to different doses of Eimeria acervulina in day-old <strong>br</strong>oilers<<strong>br</strong> />

Willem Swinkels - willem.swinkels@wur.nl .............................................................................................................................. 149<<strong>br</strong> />

Genomics and Post-genomics<<strong>br</strong> />

HAPPY mapping – a tool for genome finishing<<strong>br</strong> />

Paul H. Dear - phd@mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk ................................................................................................................................ 149<<strong>br</strong> />

Survey of Eimeria spp. Transcripts Using Open Reading Frame ESTs (Orestes)<<strong>br</strong> />

Alda M.B.N. Madeira - albackx@<strong>usp</strong>.<strong>br</strong> .................................................................................................................................. 150<<strong>br</strong> />

Molecular Characterization and Comparative Analysis of Mitochondrial Genomes of Eimeria spp.<<strong>br</strong> />

Arthur Gruber - argruber@<strong>usp</strong>.<strong>br</strong> .......................................................................................................................................... 150<<strong>br</strong> />

Molecular and Phylogenetic Features of<<strong>br</strong> />

Two Distinct dsRNA Virus Families Infecting Eimeria spp. of Domestic Fowl<<strong>br</strong> />

Jane Silveira Fraga - jane.fraga@gmail.com .......................................................................................................................... 151<<strong>br</strong> />

Long SAGE (Serial Analysis of Gene Expression) In Eimeria Tenella – A Preliminary Study<<strong>br</strong> />

Jeniffer Novaes - jeffys@ajato.com.<strong>br</strong> .................................................................................................................................... 151<<strong>br</strong> />

DNA Microarray Gene Expression Analyses in Attenuated and Virulent E. tenella<<strong>br</strong> />

Tomas Mikuš - mikus@<strong>br</strong>i.cz ................................................................................................................................................... 152<<strong>br</strong> />

Progress in the development of stable transfection in Eimeria tenella<<strong>br</strong> />

Fiona Tomley - fiona.tomley@bbsrc.ac.uk .............................................................................................................................. 152<<strong>br</strong> />

Immunology<<strong>br</strong> />

Common and Unique Gene Expression<<strong>br</strong> />

of Avian Macrophages in Response to Three Major Eimeria Species<<strong>br</strong> />

Rami A. Dalloul - rdalloul@anri.barc.usda.gov ........................................................................................................................ 153<<strong>br</strong> />

Molecular cloning and expression profiles of chicken NK-lysin during Eimeria infections<<strong>br</strong> />

Yeong H. Hong - yhong@anri.barc.usda.gov .......................................................................................................................... 153<<strong>br</strong> />

Development of future strategies for vaccinating chickens against coccidiosis using<<strong>br</strong> />

recombinant antibodies, genes and peptides.<<strong>br</strong> />

Hyun S. Lillehoj - hlilleho@anri.barc.usda.gov ......................................................................................................................... 154<<strong>br</strong> />

Genetics, immunity and DNA fingerprinting in the identification<<strong>br</strong> />

of protective antigens of Eimeria maxima<<strong>br</strong> />

Damer Peter Blake - damer.blake@bbsrc.ac.uk .................................................................................................................... 154<<strong>br</strong> />

Application of functional genomics, immunology and<<strong>br</strong> />

molecular biology tools to explore host immune response to Eimeria<<strong>br</strong> />

Hyun S. Lillehoj - hlilleho@anri.barc.usda.gov ......................................................................................................................... 155<<strong>br</strong> />

Proteins from the wall- forming bodies of Eimeria maxima: function and immunogenicity<<strong>br</strong> />

Nicholas Smith - nick.smith@uts.edu.au ................................................................................................................................. 155<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference • 15

Contents<<strong>br</strong> />

Mixed Cocciodiosis Control: Drugs and Vaccines<<strong>br</strong> />

Restoration of Field Eimeria Anticoccidial Sensitivity with Coccivac-B, a Live Coccidiosis Vaccine<<strong>br</strong> />

Greg Mathis - southern_poultry_res@msn.com ..................................................................................................................... 156<<strong>br</strong> />

Rotational Programs Combining Drugs and Coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

Vaccine Improve Performance and Profitability in a Commercial Broiler Farm<<strong>br</strong> />

Marco A. Quiroz - marco.quiroz@novusint.com ..................................................................................................................... 156<<strong>br</strong> />

Comparison of drug-sensitivity and species composition<<strong>br</strong> />

of Eimeria isolated from poultry farms<<strong>br</strong> />

Mark C. Jenkins - mjenkins@anri.barc.usda.gov .................................................................................................................... 157<<strong>br</strong> />

Higher incidence of Eimeria spp. field isolates sensitive<<strong>br</strong> />

to diclazuril and monensin after live coccidiosis vaccination with Paracox -5<<strong>br</strong> />

Wil J. M. Landman - w.landman@gdvdieren.nl ...................................................................................................................... 157<<strong>br</strong> />

Coccidiosis in Turkeys: patterns of drug response to in feed anticoccidials<<strong>br</strong> />

Marcelo Lang - marcelo.lang@spcorp.com ............................................................................................................................ 158<<strong>br</strong> />

Diagnosis and Epidemiology<<strong>br</strong> />

Sequence analysis of the 18S RNA gene of Isospora belli and identification of Caryospora-like oocysts<<strong>br</strong> />

Somchai Jongwutiwes - fmedsjw@md2.md.chula.ac.th ........................................................................................................ 158<<strong>br</strong> />

Detection and identification of<<strong>br</strong> />

Neospora caninum in a naturally infected buffalo fetus (Bubalus bubalis) from Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Solange Maria Gennari - sgennari@<strong>usp</strong>.<strong>br</strong> ............................................................................................................................. 159<<strong>br</strong> />

Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis among human immunodeficiency<<strong>br</strong> />

virus-infected patients in Thailand: analysis of the 18S RNA and the Cpg60/45/15 loci<<strong>br</strong> />

Somchai Jongwutiwes - fmedsjw@md2.md.chula.ac.th ........................................................................................................ 160<<strong>br</strong> />

Molecular Genotyping Of Eimeria tenella and E. acervulina Through microsatellite markers<<strong>br</strong> />

Arthur Gruber - argruber@<strong>usp</strong>.<strong>br</strong> .......................................................................................................................................... 161<<strong>br</strong> />

Counting coccidia: a genomic approach<<strong>br</strong> />

Damer Peter Blake - damer.blake@bbsrc.ac.uk .................................................................................................................... 162<<strong>br</strong> />

Digital Image Analysis In The Diagnosis Of Chicken Coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

Arthur Gruber - argruber@<strong>usp</strong>.<strong>br</strong> .......................................................................................................................................... 162<<strong>br</strong> />

Molecular biology and Biochemistry<<strong>br</strong> />

The Macrophage Inhibitory Factor of Eimeria species<<strong>br</strong> />

Katharzyna Miska - kmiska@anri.barc.usda.gov ................................................................................................................... 163<<strong>br</strong> />

The developmental expression of Eimeria Heat shock protein 90<<strong>br</strong> />

Katharzyna Miska - kmiska@anri.barc.usda.gov ................................................................................................................... 163<<strong>br</strong> />

Acetyl CoA Carboxylase in Avian Eimeria<<strong>br</strong> />

Patricia C. Allen - pallen@anri.barc.usda.gov ......................................................................................................................... 164<<strong>br</strong> />

The Satellite DNA Of Eimeria tenella: a Quantitative and Qualitative Study<<strong>br</strong> />

Arthur Gruber - argruber@<strong>usp</strong>.<strong>br</strong> .......................................................................................................................................... 164<<strong>br</strong> />

Characterization of Serine Proteases in Developmental Stages of Eimeria tenella.<<strong>br</strong> />

Raymond H. Fetterer - rfettere@anri.barc.usda.gov ............................................................................................................. 165<<strong>br</strong> />

Cell Biology<<strong>br</strong> />

Plastid Replication in Apicomplexan Parasites<<strong>br</strong> />

Boris Striepen - striepen@cb.uga.edu .................................................................................................................................... 165<<strong>br</strong> />

Identification and function of the EtMIC4-EtMIC5<<strong>br</strong> />

protein complex. A novel microneme complex of Eimeria tenella<<strong>br</strong> />

Fiona Tomley - fiona.tomley@bbsrc.ac.uk .............................................................................................................................. 166<<strong>br</strong> />

Characterisation of Apical Mem<strong>br</strong>ane Antigens in Eimeria tenella<<strong>br</strong> />

Fiona Tomley - fiona.tomley@bbsrc.ac.uk .............................................................................................................................. 166<<strong>br</strong> />

16 • IXth International Coccidiosis Conference

Contents<<strong>br</strong> />

Investigation of the role of proteoglycans during invasion of Eimeria tenella sporozoites<<strong>br</strong> />

Fiona Tomley - fiona.tomley@bbsrc.ac.uk .............................................................................................................................. 167<<strong>br</strong> />

Characteristic of Cryptosporidium Apical Antigens Using Chicken Monoclonal Antibodies<<strong>br</strong> />

Against Eimeria<<strong>br</strong> />

M. Matsubayashi - matsu@oyg.ac.jp ...................................................................................................................................... 167<<strong>br</strong> />

Chemotherapy<<strong>br</strong> />

Effects of Natustat supplementation on Chickens Challenged<<strong>br</strong> />

with Eimeria acervulina, Eimeria maxima and Eimeria tenella<<strong>br</strong> />

Cepta F Duffy - cduffy@alltech.com ...................................................................................................................................... 168<<strong>br</strong> />

The impact of the crowding effect of chicken Eimeria on the efficacy of anticoccidials: a hypothesis<<strong>br</strong> />

Maarten De Gussem - mdgussen@janbe.jnj.com ................................................................................................................... 168<<strong>br</strong> />

Coccidiosis control in poultry: importance of the quality of anticoccidial premixes<<strong>br</strong> />

Maarten De Gussem - mdgussen@janbe.jnj.com ................................................................................................................... 169<<strong>br</strong> />

Anticoccidial sensitivity profiles of recently obtained Dutch, German,<<strong>br</strong> />

and Spanish Eimeria spp. isolates<<strong>br</strong> />

Herman W. Peek - h.peek@gdvdieren.nl ............................................................................................................................... 170<<strong>br</strong> />

Treatment of Mice with the anticoccidial drug Toltrazuril does not interfere with the<<strong>br</strong> />

development of a specific cellular intestinal immune response to Eimeria falciformis<<strong>br</strong> />

Thomas Pogonka - thomas.pogonka@rz.hu-berlin.de ........................................................................................................... 171<<strong>br</strong> />

The impact of coccidial drug-resistance on the commercial performance of <strong>br</strong>oilers<<strong>br</strong> />

Raymond Barry Williams - ray.coxitec@texco.net ................................................................................................................... 171<<strong>br</strong> />

Pathology<<strong>br</strong> />

Chicken coccidiosis: a fresh look at lesions<<strong>br</strong> />

Raymond Barry Williams - ray.coxitec@texco.net ................................................................................................................... 172<<strong>br</strong> />

The Stealth Chicken Eimeria: E. mivati - a new perspective<<strong>br</strong> />

Steve Fitz-Coy - steve.fitz-coy@spcorp.com .......................................................................................................................... 173<<strong>br</strong> />

The Role of E. mitis in Chicken Coccidiosis: a Study of Pathogenicity<<strong>br</strong> />

Luciano Gobbi - luciano.gobbi@spcorp.com ........................................................................................................................... 173<<strong>br</strong> />

The comparison and validation of methods for monitoring coccidiosis in <strong>br</strong>oilers<<strong>br</strong> />

Christiaan le Roux - corne.loots@spcorp.com ......................................................................................................................... 174<<strong>br</strong> />

Comparison of E. acervulina oocyst counts in single droppings of <strong>br</strong>oilers and in droppings<<strong>br</strong> />

collected during 24 hours<<strong>br</strong> />

Francisca C. Velkers - f.c.velkers@vet.uu.nl............................................................................................................................ 174<<strong>br</strong> />

Reasons for Field Problems with Eimeria maxima: E. acervulina versus E. maxima<<strong>br</strong> />

Greg Mathis - southern_poultry_res@msn.com.<strong>br</strong> ................................................................................................................ 175<<strong>br</strong> />

Contributed Papers: Posters<<strong>br</strong> />

Diagnosis and Epidemiology<<strong>br</strong> />

Comparison between the Modified Ziehl-Neelsen and Fluorescent Antibody Tests for the<<strong>br</strong> />

detection of Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts in faeces<<strong>br</strong> />

Ralph Marshall - r.n.marshall@vla.dfra.gsi.gov.uk ................................................................................................................... 179<<strong>br</strong> />

Occurrence of Toxoplama gondii antibodies in fattening pigs from the State of São Paulo, Brazil<<strong>br</strong> />

Solange Maria Gennari - sgennari@<strong>usp</strong>.<strong>br</strong> ............................................................................................................................. 179<<strong>br</strong> />

Prevalence of <strong>Coccidia</strong> in French Calves: Results of Several Surveys<<strong>br</strong> />

Alain Richard - alain.richard@alpharma.com .......................................................................................................................... 180<<strong>br</strong> />

Study on the ability of water supply to contaminate poultry flocks with coccidia<<strong>br</strong> />

Jean Michel Reperant - jm.reperant@afssa.fr ....................................................................................................................... 181<<strong>br</strong> />

Evaluation of a rapid screening assay<<strong>br</strong> />

for Cryptosporidium identification (DOT-ELISA) using monoclonal antibody<<strong>br</strong> />

Elisabeth Natal de Gaspari - egaspari@ial.sp.gov.<strong>br</strong> ............................................................................................................... 181<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference • 17

Contents<<strong>br</strong> />

Eimeria Species Identification In Faeces And Litter Samples From Chickens<<strong>br</strong> />

Anita Haug - anita.haug@vetinst.no ...................................................................................................................................... 182<<strong>br</strong> />

Determination of the Sensitivity of the Serial Scraping<<strong>br</strong> />

Method of Intestinal Mucosa in the Diagnosis of Subclinical Coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

Mauricio De Franceschi - mauriciodf@datamarkets.com.ar .................................................................................................. 183<<strong>br</strong> />

Identification of <strong>Coccidia</strong> Species in Broiler Chickens in Argentina<<strong>br</strong> />

Hernán González - sp@mail.unlu.edu.ar ................................................................................................................................ 183<<strong>br</strong> />

Development of a histological scoring model for use in interpreting the immune response<<strong>br</strong> />

David Grant Richards - medichick@ava.com.au ..................................................................................................................... 184<<strong>br</strong> />

Progress Toward The Development Of Serological Tests For Diagnosis Of Coccidiosis In Chickens<<strong>br</strong> />

David Grant Richards - medichick@ava.com.au ..................................................................................................................... 185<<strong>br</strong> />

Characterization of cryptic field isolates of Eimeria spp. from chickens<<strong>br</strong> />

David Grant Richards - medichick@ava.com.au ..................................................................................................................... 185<<strong>br</strong> />

Pathology<<strong>br</strong> />

Experimental production of necrotic enteritis and its use for studies on the relationships<<strong>br</strong> />

between necrotic enteritis and coccidiosis in chickens<<strong>br</strong> />

Ralph Marshall - r.n.marshall@vla.dfra.gsi.gov.uk ................................................................................................................... 186<<strong>br</strong> />

Clinical And Pathological Changes In Chickens (Gallus domesticus) Experimentally Infected<<strong>br</strong> />

with Eimeria acervulina (TIZZER, 1929) oocysts<<strong>br</strong> />

Rosangela Z. Machado - zacarias@fcav.unesp.<strong>br</strong> .................................................................................................................. 186<<strong>br</strong> />

Association between <strong>Coccidia</strong> and Intestinal Helmints in Broiler Chickens<<strong>br</strong> />

Mauricio Enrique de Franceschi - sip@mail.unlu.edu.ar ......................................................................................................... 187<<strong>br</strong> />

Phenotypic characterization of chicken selection lines infected with Eimeria tenella<<strong>br</strong> />

Giovani Rota Bertani - gbertani@cnpsa.em<strong>br</strong>apa.<strong>br</strong> .............................................................................................................. 187<<strong>br</strong> />

Necrotic Enteritis Association with Eimeria acervulina and E. maxima<<strong>br</strong> />

Greg Mathis - southern_poultry_res@msn.com ..................................................................................................................... 188<<strong>br</strong> />

Interaction of E. coli O157:H7 with Cryptosporidium parvum in 6-week-old lambs<<strong>br</strong> />

Ralph Marshall - r.n.marshall@vla.dfra.gsi.gov.uk ................................................................................................................... 189<<strong>br</strong> />

Application of Eimeria maxima to a Clostridium perfringens-associated necrotic enteritis<<strong>br</strong> />

model for studying bacterial competitive exclusion in poultry<<strong>br</strong> />

Ralph Marshall - r.n.marshall@vla.dfra.gsi.gov.uk ................................................................................................................... 189<<strong>br</strong> />

Immunology<<strong>br</strong> />

Cryptosporidium parvum cellular recruitment during the inflammatory response in mice<<strong>br</strong> />

Elisabeth Natal de Gaspari - egaspari@ial.sp.gov.<strong>br</strong> ............................................................................................................... 190<<strong>br</strong> />

Vaccines<<strong>br</strong> />

The Use Of A Viability Assay To Formulate A New Coccidiosis Vaccine<<strong>br</strong> />

Marco A. Quiroz - marco.quiroz@novusint.com ..................................................................................................................... 190<<strong>br</strong> />

Comparison of the onset of an immune response using three oocyst vaccination strategies<<strong>br</strong> />

David Grant Richards - medichick@ava.com.<strong>br</strong> ...................................................................................................................... 191<<strong>br</strong> />

Quantization of Plasma D-Xylose Concentration Following of Vaccination against Coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

and Experimental Subclinical Coccidiosis Induced by Eimeria maxima in Broilers<<strong>br</strong> />

Seyed Shapoor Reza Shojaei - vetparasitologist@yahoo.com ................................................................................................ 191<<strong>br</strong> />

Chemotherapy<<strong>br</strong> />

Relationship of E. acervulina Ionophore Resistance to Field Problems with E. maxima<<strong>br</strong> />

Greg Mathis - southern_poultry_res@msn.com ..................................................................................................................... 192<<strong>br</strong> />

Efficacy of decoquinate at different administration<<strong>br</strong> />

strategies against cryptosporidiosis in natural infected cashmere goat kids<<strong>br</strong> />

Alain Richard - alain.richard@alpharma.com .......................................................................................................................... 193<<strong>br</strong> />

Efficacy of toltrazuril and amprolium against turkey coccidiosis caused by a mixed E.<<strong>br</strong> />

adenoeides and E. meleagrimitis infection<<strong>br</strong> />

Ro<strong>br</strong>echt Froyman - ro<strong>br</strong>echt.froyman@bayerhealthcare.com ............................................................................................. 194<<strong>br</strong> />

Author Index .................................................................................................................... 195<<strong>br</strong> />

18 • IXth International Coccidiosis Conference

The IX th International<<strong>br</strong> />

Coccidiosis Conference<<strong>br</strong> />

is dedicated to Dr. Peter Long

Professor Peter L. Long: an Appreciation<<strong>br</strong> />

Professor Peter L. Long: an Appreciation<<strong>br</strong> />

M. W. Shirley<<strong>br</strong> />

Institute for Animal Health, Compton Laboratory, Compton, Newbury, Berks. RG 20 7NN, UK, shirley@bbsrc.ac.uk<<strong>br</strong> />

If asked to think of the most influential coccidiologist of the past four decades, the chances are that the<<strong>br</strong> />

name of Peter Long will feature at, or near, the top of most people’s lists. If asked to think of the most<<strong>br</strong> />

influential coccidiologist of the past four decades who is also the most approachable and sociable, the<<strong>br</strong> />

likelihood is that Peter will be at the top of everyone’s list! Peter has the rare gift of scientific excellence<<strong>br</strong> />

combined with a warm demeanour and fondness for bon homie that has endeared him to all who have<<strong>br</strong> />

had the pleasure of his acquaintance.<<strong>br</strong> />

I first became a colleague in 1967 when I started work at the Houghton Poultry Research Station (HPRS)<<strong>br</strong> />

where Peter was a principal scientist looking to recruit a new member of his team. At that time he had<<strong>br</strong> />

not yet gained his PhD but he was established comfortably as a coccidiologist of increasing international<<strong>br</strong> />

renown and was a natural successor to Clifford Horton-Smith who had also previously graced HPRS with<<strong>br</strong> />

distinction and charisma. A symmetry in the three generations was to emerge - Clifford had been a<<strong>br</strong> />

mentor to Peter as Peter was to become to me. Moreover, there was to be further symmetry in the way<<strong>br</strong> />

that the academic career of Peter developed subsequently with how mine was to shape up under his<<strong>br</strong> />

guidance.<<strong>br</strong> />

Edward Tyzzer was working on his Magnum Opus to be published in 1929 when Peter was born in<<strong>br</strong> />

London in 1928. Peter developed into a good sportsman with a special love of cricket – a game at which<<strong>br</strong> />

he was especially skilled and which he played on-and-off for several decades. He supplemented his<<strong>br</strong> />

cricket with both hockey and squash and his competitive nature at sports was mirrored by his determination<<strong>br</strong> />

to succeed professionally.<<strong>br</strong> />

He began his professional life working on poultry parasites at the Central Veterinary Laboratory at<<strong>br</strong> />

Wey<strong>br</strong>idge, Surrey as a laboratory technician with Dr Clifford Horton-Smith. Only four years later, however,<<strong>br</strong> />

he was conscripted into the Royal Army Medical Corps and served in Egypt, Malta and Palestine.<<strong>br</strong> />

In 1949, following demobilisation, Peter and Clifford were reunited at the Ashford Hospital, Middlesex<<strong>br</strong> />

and then a more durable union followed with their relocation to the HPRS: Peter becoming the research<<strong>br</strong> />

technician for Horton-Smith within the Parasitology department working on a programme of research<<strong>br</strong> />

directed principally towards coccidiosis of poultry. Without any formal academic qualifications, Peter<<strong>br</strong> />

studied part-time to become a Member of the Institute of Medical Laboratory Technology in 1952 and<<strong>br</strong> />

obtained Fellow status by thesis in 1956.<<strong>br</strong> />

A steady stream of publications was beginning to appear and a strong desire to publish his data was to<<strong>br</strong> />

define his entire working life. Some early publications included a very useful treatise on E. maxima [Long,<<strong>br</strong> />

P. L. (1959). A study of Eimeria maxima Tyzzer, 1929, A coccidium of the fowl (Gallus gallus). Annals of<<strong>br</strong> />

Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, 53, 325–333] that remains one of the few definitive studies on this<<strong>br</strong> />

major avian species. By now Peter was progressing through the ranks from his original grading of “Assistant<<strong>br</strong> />

Experimental Officer” such that by 1963 he was able to spend a sabbatical year at Cornell University in<<strong>br</strong> />

the USA working with the eminent poultry pathologist, Professor P. P. Levine. This very positive scientific<<strong>br</strong> />

experience left an indelible mark on his subsequent career and much later he was to return to the USA<<strong>br</strong> />

to the University of Georgia where he spent the final 10 years of his active working life.<<strong>br</strong> />

Peter’s taste for working a<strong>br</strong>oad was strengthened in 1963 and 1964 with two visits to the Lebanon,<<strong>br</strong> />

where he worked on poultry coccidiosis and taught parasitology at the Institut de Recherches Agronomiques.<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference • 21

Professor Peter L. Long: an Appreciation<<strong>br</strong> />

In 1964, and through further part time studies, Peter became a member of the Institute of Biology in the<<strong>br</strong> />

UK and in 1971 Peter was awarded a PhD by Brunel University for his work on the avian coccidia and in<<strong>br</strong> />

1977 was awarded a DSc. His association with Brunel University led to a strong friendship with Professor<<strong>br</strong> />

Roland J. Terry, who subsequently paid a professional visit to Peter when he was at Athens.<<strong>br</strong> />

Throughout the 1960’s and 1970’s Peter maintained a high output of publications from the parasitologists<<strong>br</strong> />

at HPRS with an impressive list of personal papers that laid much of the groundwork for later developments<<strong>br</strong> />

in the control and study of the avian coccidia including:<<strong>br</strong> />

• two of the few papers on Eimeria to be published in the journal Nature [Long, P. L. (1965). Development<<strong>br</strong> />

of Eimeria tenella in avian em<strong>br</strong>yos. Nature 208, 509-10 and Long, P. L. (1970c). Development<<strong>br</strong> />

(schizogony) of Eimeria tenella in the liver of chickens treated with corticosteroid. Nature 225, 290-1]<<strong>br</strong> />

• pioneering studies on the growth of different species of Eimeria in avian em<strong>br</strong>yos that would eventually<<strong>br</strong> />

help in the development of live attenuated vaccines [Long, P. L. (1966). The growth and attenuation of<<strong>br</strong> />

some species of Eimeria in avian em<strong>br</strong>yos. Parasitology 56, 575-81 and Long, P. L. (1972b). Eimeria<<strong>br</strong> />

tenella: reproduction, pathogenicity and immunogenicity of a strain maintained in chick em<strong>br</strong>yos by<<strong>br</strong> />

serial passage. J Comp Pathol 82, 429-37]<<strong>br</strong> />

• the isolation and identification of different species [e.g. Long, P. L. (1973c). Studies on the relationship<<strong>br</strong> />

between Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria mivati. Parasitology 67, 143-55 and Long, P. L. (1974). Experimental<<strong>br</strong> />

infection of chickens with two species of Eimeria isolated from the Malaysian jungle fowl.<<strong>br</strong> />

Parasitology 69, 337-47]<<strong>br</strong> />

• studies on immunity, often with Elaine Rose [Long, P. L., and Rose, M. E. (1972). Immunity to coccidiosis:<<strong>br</strong> />

effect of serum antibodies on cell invasion by sporozoites of Eimeria in vitro. Parasitology 65, 437-45<<strong>br</strong> />

• studies on chemotherapy [Long, P. L., and Millard, B. J. (1968). Eimeria: effect of meticlorpindol and<<strong>br</strong> />

methyl benzoquate on endogenous stages in the chicken. Exp Parasitol 23, 331-8]<<strong>br</strong> />

• the first studies to provide quantitative data on the incidence of Eimeria species in poultry houses<<strong>br</strong> />

[Long, P. L., Tompkins, R. V., and Millard, B. J. (1975). Coccidiosis in <strong>br</strong>oilers: evaluation of infection by<<strong>br</strong> />

the examination of <strong>br</strong>oiler house litter for oocysts. Avian Pathology 4, 287-294].<<strong>br</strong> />

This was indeed a golden period for Peter and his acclaim grew within HPRS, where he was appointed<<strong>br</strong> />

successor to Dr Donald L. Lee as Head of Parasitology in 1972; nationally, for example, he was awarded<<strong>br</strong> />

the Tom Newman Medal for Poultry Research from the British Poultry Breeders and Hatcheries Association<<strong>br</strong> />

in 1971 and made an honorary member of the British Veterinary Poultry Association in 1972; and<<strong>br</strong> />

internationally where he consolidated his position as arguably the leading scientist working on the biology<<strong>br</strong> />

of avian coccidia.<<strong>br</strong> />

In 1973 Peter worked with Datus M. Hammond to edit “The coccidia”, a book that was to become the<<strong>br</strong> />

first in a series of volumes on the biology of the coccidia and coccidiosis. These books, most especially the<<strong>br</strong> />

1982 volume entitled “The biology of the coccidia” have stood the test of time and continue to be some<<strong>br</strong> />

of the most used reference texts. The most recent volume, now over 15 years old and entitled “Coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

in man and domestic animals”, is a further reflection of Peter’s commitment and ability to work with<<strong>br</strong> />

others to effectively deliver knowledge of the avian coccidia into the public domain.<<strong>br</strong> />

Within the UK Peter helped to establish the forum that is now known as the European Coccidiosis<<strong>br</strong> />

Discussion Group and he was one of the founding members of what was to become the British Society for<<strong>br</strong> />

Parasitology, which later made him an honorary member.<<strong>br</strong> />

In 1979, Peter left the HPRS to succeed Professor W. Malcolm Reid as Professor of Parasitology and<<strong>br</strong> />

Chairman of the Faculty of Parasitology at the University of Georgia. In 1983, Peter was further recognised<<strong>br</strong> />

22 • IXth International Coccidiosis Conference

Professor Peter L. Long: an Appreciation<<strong>br</strong> />

by the University by the title, which he held until 1990 when he retired back to the UK, of D.W. Brooks<<strong>br</strong> />

Distinguished Professor of Poultry Science.<<strong>br</strong> />

During his years at HPRS, Peter was most ably supported scientifically and technically by Brian Millard<<strong>br</strong> />

and, if there were an equivalent anywhere else in the world, he most definitely found that person in Joyce<<strong>br</strong> />

Johnson. Peter and Joyce developed a wonderful working rapport and the transition of his science from<<strong>br</strong> />

HPRS to the University of Georgia seemed almost seamless with virtually no interruption to the stream of<<strong>br</strong> />

papers.<<strong>br</strong> />

Peter’s later contributions to coccidiosis research continued to reflect his desire to improve and understand<<strong>br</strong> />

the control of disease and his early work in Georgia was pivotal to the first understandings of the relationship<<strong>br</strong> />

between pathological changes in the intestines and body weight changes of vaccinated or naive chickens<<strong>br</strong> />

after challenge, findings that were to become important considerations in the evaluation of vaccines [e.g.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Johnson, J., and Wyatt, R. D. (1980). Eimeria tenella: clinical effects in partially immune and<<strong>br</strong> />

susceptible chickens. Poult Sci 59, 2221-4]. In addition he pursued work in the USA on the development<<strong>br</strong> />

of precocious, attenuated lines of Eimeria as well as addressing issues of disease control more generally.<<strong>br</strong> />

In total, Peter published more than 200 scientific papers, countless popular articles and very many book<<strong>br</strong> />

chapters. He also helped stage the Coccidiosis Conference in Georgia in 1985.<<strong>br</strong> />

The scientific excellence of Peter and his contribution to research on coccidia and coccidiosis has been<<strong>br</strong> />

recognised many times and, in addition to the Tom Newman Award, he was the first recipient of the<<strong>br</strong> />

Gordon Memorial Medal (1983); the Merck Award for Research from the American Poultry Science<<strong>br</strong> />

Association (1984); and the Creative Research Medal from the University of Georgia, Athens.<<strong>br</strong> />

Throughout his career Peter influenced and mentored many colleagues including several PhD students<<strong>br</strong> />

(about whom he still speaks with great warmth and pride) as well as many more established researchers<<strong>br</strong> />

across the globe. He enjoyed interacting with, or working alongside, such luminaries as Alan Pierce,<<strong>br</strong> />

Akira Arakawa, Stan Ball, Peter Bedrnik, David Chapman, Aggie Fernando, Datus Hammond, Thomas<<strong>br</strong> />

Jeffers, Joyce Johnson, Len Joyner, P. P. Levine Lazlo Pellerdy, Larry McDougald, Malcolm Reid, Elaine<<strong>br</strong> />

Rose, Erich Scholtyseck and Ray Williams, to name just a few.<<strong>br</strong> />

When David Chapman and I published a recent history of the Houghton strain, a strain that is now so<<strong>br</strong> />

firmly embedded within research into Eimeria spp. as the parasite used for the derivation of a genome<<strong>br</strong> />

sequence, we dedicated the paper to both Peter Long and Elaine Rose. Without the direct inputs of Peter<<strong>br</strong> />

on both the science and the people, the current landscape of coccidiosis research would almost certainly<<strong>br</strong> />

be very different from what we have now and probably less at the cutting-edge of microbiological research.<<strong>br</strong> />

Many of us working on Eimeria parasites might care to reflect upon the words of Isaac Newton to Robert<<strong>br</strong> />

Hooke on 5th. Fe<strong>br</strong>uary 1676, that “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants”.<<strong>br</strong> />

Peter Long is a giant in the history of coccidiosis research.<<strong>br</strong> />

A SELECTION OF OTHER PUBLICATIONS BY PETER LONG THAT FURTHER ILLUSTRATES HIS VERY SIGNIFICANT<<strong>br</strong> />

CONTRIBUTION TO STUDIES ON THE AVIAN COCCIDIA<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1967). Studies on Eimeria mivati in chickens and a comparison with Eimeria acervulina. J Comp Pathol<<strong>br</strong> />

77, 315-25.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Millard, B. J. (1967). The effect of Meticlorpindol on Eimeria infections of the fowl. Vet Rec 81, 11-<<strong>br</strong> />

5.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1968). The effect of <strong>br</strong>eed of chickens on resistance to Eimeria infections. Br Poult Sci 9, 71-8.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1968). The pathogenic effects of Eimeria praecox and E. acervulina in the chicken. Parasitology 58, 691-<<strong>br</strong> />

700.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Horton-Smith, C. (1968). <strong>Coccidia</strong> and coccidiosis in the domestic fowl. Adv Parasitol 6, 313-25.<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference • 23

Professor Peter L. Long: an Appreciation<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1969). Observations on the growth of Eimeria tenella in cultured cells from the parasitized chorioallantoic<<strong>br</strong> />

mem<strong>br</strong>anes of the developing chick em<strong>br</strong>yo. Parasitology 59, 757-65.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1970). Coccidiosis: development of new techniques in coccidiostat evaluation. Exp Parasitol 28, 151-<<strong>br</strong> />

5.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1970). Eimeria tenella: chemotherapeutic studies in chick em<strong>br</strong>yos with a description of a new method<<strong>br</strong> />

(chorioallantoic mem<strong>br</strong>ane foci counts) for evaluating infections. Z Parasitenkd 33, 329-38.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1970). Some factors affecting the severity of infection with Eimeria tenella in chicken em<strong>br</strong>yos. Parasitology<<strong>br</strong> />

60, 435-47.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1970). Studies on the viability of sporozoites of Eimeria tenella. Z Parasitenkd 35, 1-6.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Rose, M. E. (1970). Extended schizogony of Eimeria mivati in betamethasone-treated chickens.<<strong>br</strong> />

Parasitology 60, 147-55.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Milne, B. S. (1971). The effect of an interferon inducer on Eimeria maxima in the chicken. Parasitology<<strong>br</strong> />

62, 295-302.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1971). Schizogony and gametogony of Eimeria tenella in the liver of chick em<strong>br</strong>yos. J Protozool 18, 17-<<strong>br</strong> />

20.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1972). Eimeria mivati: reproduction, pathogenicity and immunogenicity of a strain maintained in chick<<strong>br</strong> />

em<strong>br</strong>yos by serial passage. J Comp Pathol 82, 439-45.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1972). Observations on the oocyst production and viability of Eimeria mivati and E. tenella in the<<strong>br</strong> />

chorioallantois of chicken em<strong>br</strong>yos incubated at different temperatures. Z Parasitenkd 39, 27-37.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Burns Brown, W., and Goodship, G. (1972). The effect of methyl <strong>br</strong>omide on coccidial oocysts determined<<strong>br</strong> />

under controlled conditions. Vet Rec 90, 562-7.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1973). Endogenous stages of a ‘chick em<strong>br</strong>yo-adapted’ strain of Eimeria tenella. Parasitology 66, 55-<<strong>br</strong> />

62.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1973). The growth of avian coccidia in the developing chick em<strong>br</strong>yo and in cultured cells . Folia Vet Lat<<strong>br</strong> />

3, 89-109.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Fernando, M. A., and Remmler, O. (1974). Experimental infections of the domestic fowl with a variant<<strong>br</strong> />

of Eimeria praecox from the Ceylon jungle fowl. Parasitology 69, 1-9.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Rowell, J. G. (1975). Sampling <strong>br</strong>oiler house litter for coccidial oocysts. Br Poult Sci 16, 583-92.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Millard, B. J., Joyner, L. P., and Norton, C. C. (1976). A guide to laboratory techniques used in the study<<strong>br</strong> />

and diagnosis of avian coccidiosis. Folia Vet Lat 6, 201-17.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Millard, B. J. (1976). The detection of occult coccidial infections by inoculating chickens with<<strong>br</strong> />

corticosteroid drugs. Z Parasitenkd 48, 287-90.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Millard, B. J. (1976). Studies on site finding and site specificity of Eimeria praecox, Eimeria maxima<<strong>br</strong> />

and Eimeria acervulina in chickens. Parasitology 73, 327-36.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Rose, M. E. (1976). Growth of Eimeria tenella in vitro in macrophages from chicken peritoneal<<strong>br</strong> />

exudates. Z Parasitenkd 48, 291-4.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Millard, B. J., and Shirley, M. W. (1977). Strain variations within Eimeria meleagrimitis from the turkey.<<strong>br</strong> />

Parasitology 75, 177-82.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Millard, B. J. (1978). Coccidiosis in <strong>br</strong>oilers: the effect of monensin and other anticocidial drug<<strong>br</strong> />

treatments on oocyst output. Avian Pathology 7, 373-381.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Millard, B. J. (1978). Studies on Eimeria grenieri in the guinea fowl (Numida meleagris). Parasitology<<strong>br</strong> />

76, 1-9.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Millard, B. J. (1979). Immunological differences in Eimeria maxima: effect of a mixed immunizing<<strong>br</strong> />

inoculum on heterologous challenge. Parasitology 79, 451-7.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Millard, B. J. (1979). Rejection of Eimeria by foreign hosts. Parasitology 78, 239-47.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Millard, B. J. (1979). Studies on Eimeria dispersa Tyzzer 1929 in turkeys. Parasitology 78, 41-52.<<strong>br</strong> />

24 • IXth International Coccidiosis Conference

Professor Peter L. Long: an Appreciation<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Millard, B. J., and Lawn, A. M. (1979). An unusual local reaction to an intracellular protozoon parasite<<strong>br</strong> />

Eimeria dispersa. Z Parasitenkd 60, 193-5.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1970). Anticoccidial drugs: factors affecting pathogenicity of avian coccidia. Exp Parasitol 28, 4-10.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Johnson, J., and Reyna, P. (1980). The use of sentinel birds to monitor coccidial infection in litter pens.<<strong>br</strong> />

Avian Dis 24, 435-45.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Johnson, J., and Wyatt, R. D. (1980). Eimeria tenella: clinical effects in partially immune and susceptible<<strong>br</strong> />

chickens. Poult Sci 59, 2221-4.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Johnson, J., and Wyatt, R. D. (1981). Pathological and clinical effects of Eimeria tenella in partially<<strong>br</strong> />

immune chickens. J Comp Pathol 91, 581-7.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Jeffers, T. K. (1982). Studies on the stage of action of ionophorous antibiotics against Eimeria. J<<strong>br</strong> />

Parasitol 68, 363-71.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Johnson, J., and Gore, T. C. (1982). Attenuation of a strain of Eimeria mivati of U.S. origin by serial<<strong>br</strong> />

em<strong>br</strong>yo passage. Avian Dis 26, 305-13.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L. (1984). Gordon memorial lecture. Coccidiosis control: past, present and future. Br Poult Sci 25, 3-18.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., and Joyner, L. P. (1984). Problems in the identification of species of Eimeria. J Protozool 31, 535-41.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Johnson, J., and Baxter, S. (1985). Eimeria tenella: relative survival of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive<<strong>br</strong> />

populations in floor pen chickens. Poult Sci 64, 2403-5.<<strong>br</strong> />

Long, P. L., Johnson, J., and McKenzie, M. E. (1988). Anticoccidial activity of combinations of narasin and nicarbazin.<<strong>br</strong> />

Poult Sci 67, 248-52.<<strong>br</strong> />

IXth International Coccidiosis Conference • 25

Plenary<<strong>br</strong> />

Lectures

Plenary Lectures<<strong>br</strong> />

Eight decades of research on Eimeria in poultry<<strong>br</strong> />

M. W. Shirley 1 and H. David Chapman 2<<strong>br</strong> />

1<<strong>br</strong> />

Institute for Animal Health, Compton Laboratory, Compton, Newbury, Berks. RG 20 7NN, UK, shirley@bbsrc.ac.uk<<strong>br</strong> />

2<<strong>br</strong> />

Department of Poultry Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, 72701, USA.<<strong>br</strong> />

OVERVIEW<<strong>br</strong> />

For around 80 years, the amount of knowledge gathered on the avian coccidial parasites and the disease<<strong>br</strong> />

of coccidiosis has been impressive and research remains at the cutting-edge of what is being undertaken<<strong>br</strong> />

in Microbiology more generally. Research in to avian coccidiosis has been exceptionally well served and<<strong>br</strong> />

the starting point for knowledge gathering of the disease and the parasites of poultry stems from pioneering<<strong>br</strong> />

studies conducted in the 1920’s and 1930’s by investigators who, with limited experimental facilities,<<strong>br</strong> />

were able to establish many basic principles, such as life cycles, epidemiology and control of the Eimeria<<strong>br</strong> />

parasite, that are still relevant today.<<strong>br</strong> />

In the years that followed, research was conducted at institutions in the academic, government, and<<strong>br</strong> />

private sectors with the specialized facilities, especially access to buildings that prevented chances of<<strong>br</strong> />

extraneous infections of the hosts. Much of the work in the early period focused on the obvious practical<<strong>br</strong> />

control of Eimeria spp. and was supplemented by the acquisition of much basic information on the<<strong>br</strong> />

biology of the parasites, including host-parasite relationships, genetics, immunology, and pathology and<<strong>br</strong> />

some of this information was to lay the foundation for the introduction of a series of strategies to control<<strong>br</strong> />

the parasites by vaccination of the hosts.<<strong>br</strong> />

Building on the early discoveries, the control of coccidiosis by chemotherapy was introduced and, by<<strong>br</strong> />

eliminating mass out<strong>br</strong>eaks of disease, it became a critical lynchpin in the expansion of the international<<strong>br</strong> />

poultry industry. Today, chemotherapy remains the dominant method of control but the use of live vaccines<<strong>br</strong> />

has a similar long history through the early work of Allen Edgar and others. The dramatic attenuation of<<strong>br</strong> />

the life cycle of E. tenella, as first described by Thomas Jeffers in the mid 1970’s, was to lead to the<<strong>br</strong> />

selection of “precocious” lines of all species and these parasites, with their ab<strong>br</strong>eviated life cycles and<<strong>br</strong> />

marked attenuation of virulence, proved to be a significant development as they led to a new generation<<strong>br</strong> />

of safe coccidiosis vaccines. Towards the end of the 20 th century much interest was being directed<<strong>br</strong> />