about the writers⦠- International Clarinet Association

about the writers⦠- International Clarinet Association

about the writers⦠- International Clarinet Association

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

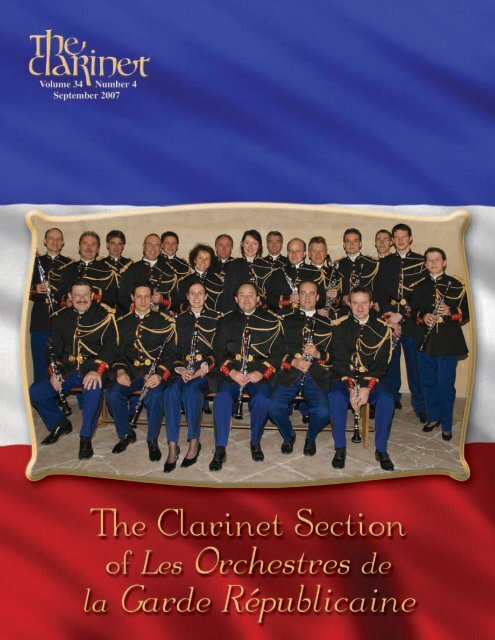

Volume 34, Number 4 September 2007<br />

ABOUT THE COVER…<br />

The clarinet section of Les Orchestres de la<br />

Garde Républicaine, Paris, France. First row<br />

(seated, l to r): André Moreau, Pascal<br />

Beauvineau, Christelle Pochet, Gilles<br />

Clermont, Pierre Ragu, Fabian Lefèvre;<br />

second row (standing, l to r): Frank Amet,<br />

Sylvain Magnolini, Philippe Montury,<br />

Denis Mayeux, Thierry Marcher, Claire<br />

Vergnory, François Dartinet, Sandrine<br />

Vasseur, Christian Roca, Thierry Vaysse<br />

(Eb clarinet), Rémy Lerner (bass clarinet),<br />

Olivier Patey (principal and bass<br />

clarinet), Bruno Dubois, Vincent Penot<br />

(principal), Sylvie Hue (principal) (photo by<br />

Philippe Bague) See article on page 50.<br />

INDEX OF ADVERTISERS<br />

Alea Publishing .........................................................82<br />

Ben Armato .................................................................7<br />

Backun Musical Services........................................IBC<br />

Charles Bay ...............................................................76<br />

Kristin Bertrand Woodwind Repair...........................67<br />

The Boston Conservatory ..........................................10<br />

Brannen Woodwinds .................................................16<br />

Buffet Crampon USA, Inc. ......................................IFC<br />

CalArts School of Music ...........................................71<br />

Centaur Records Inc. .................................................77<br />

Classical Collection Inc.............................................28<br />

Cleveland Institute of Music......................................31<br />

Crane School of Music —<br />

Potsdam Single Reed Summit .................................5<br />

Crystal Records .........................................................79<br />

DePaul University School of Music ..........................51<br />

Elkhart Musical Services...........................................33<br />

Expert Woodwind Service, Inc..................................30<br />

Clare Fischer..............................................................73<br />

Leblanc (Conn-Selmer) .........................................OBC<br />

Lisa’s <strong>Clarinet</strong> Shop ..................................................40<br />

Luyben Music Co. .....................................................53<br />

Lynn University Conservatory of Music...................65<br />

Muncy Winds ............................................................23<br />

Naylor’s Custom Wind Repair ..................................68<br />

Richard Nunemaker...................................................69<br />

Olivieri Reeds............................................................74<br />

Ongaku Records, Inc. ..................................................5<br />

Orsi & Weir ...............................................................44<br />

Edward Palanker........................................................70<br />

Patricola Bro<strong>the</strong>rs ......................................................18<br />

Pyne Clarion Inc. .......................................................21<br />

Quodlibet, Inc. ...........................................................67<br />

RedwineJazz ........................................................42, 55<br />

Reeds Australia..........................................................42<br />

Rice University —<br />

The Shepherd School of Music .............................84<br />

Rico............................................................................81<br />

Luis Rossi ..................................................................45<br />

San Francisco Conservatory of Music.......................17<br />

Sayre Woodwinds........................................................5<br />

Dr. Allan Segal ..........................................................42<br />

Selmer Paris (Conn-Selmer)........................................2<br />

The Steinhardt School of Culture, Education,<br />

and Human Development ......................................15<br />

Tap Music Sales ........................................................82<br />

Margaret Thornhill ....................................................55<br />

University of Illinois....................................................8<br />

Van Cott Information Services..................................13<br />

Vandoren SAS .................................................4, 41, 83<br />

Wehr’s Music House .................................................28<br />

Wichita Band Instrument Co. ....................................20<br />

Woodwindiana, Inc....................................................37<br />

Yamaha Corporation of America ..............................43<br />

Features<br />

BENNY GOODMAN —<br />

THE CLASSICAL CLARINETIST — PART 1 by Maureen Hurd ........32<br />

THE CLARINETISTS OF THE<br />

JOHN PHILIP SOUSA BAND: 1892–1931 by Jesse Krebs ..................39<br />

THE CLARINET SECTION OF LES ORCHESTRES<br />

DE LA GARDE RÉPUBLICAINE by Sylvie Hue....................................50<br />

IN MEMORIAM: DAME THEA KING by David Campbell.................54<br />

IN MEMORIAM: ALVIN BATISTE.....................................................54<br />

IN MEMORIAM: MICHAEL SULLIVAN by Denise A. Gainey...........55<br />

DON’T LET IT END —<br />

PART II: BOBBY GORDON by Eleisa Marsala Trampler......................56<br />

THE CLARINET TEACHING OF<br />

KEITH STEIN — PART 20: TEACHING THE<br />

CLARINET TO CHILDREN by David Pino ..........................................61<br />

A CLARINETIST’S JOURNEY OF THE SPIRIT by Joe Rosen........64<br />

EDINBURGH SHACKLETON COLLECTION —<br />

A CELEBRATION by Eric Hoeprich ......................................................78<br />

Departments<br />

LETTERS...................................................................................................5<br />

TEACHING CLARINET by Michael Webster ..........................................6<br />

CLARINOTES ........................................................................................11<br />

AUDIO NOTES by William Nichols .........................................................13<br />

CONFERENCES & WORKSHOPS.....................................................16<br />

HISTORICALLY SPEAKING… by Deborah Check Reeves..................19<br />

LETTER FROM THE U.K. by Paul Harris...........................................20<br />

THE JAZZ SCENE by Thomas W. Jacobsen............................................22<br />

UNIVERSITY SNAPSHOTS by Peggy Dees .........................................24<br />

THE CLARINET CHOIR by Margaret Thornhill...................................28<br />

REVIEWS................................................................................................66<br />

MUSICAL CHAIRS ...............................................................................78<br />

RECITALS AND CONCERTS..............................................................80<br />

THE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE by Lee Livengood ..............................82<br />

September 2007 Page 1

INTERNATIONAL CLARINET ASSOCIATION<br />

President: Lee Livengood, 490 Northmont Way, Salt Lake City, UT 84103, E-mail: <br />

Past President: Robert Walzel, School of Music, University of Utah, 204 David P. Gardner Hall, 1375 East Presidents<br />

Circle, Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0030, 801/273-0805 (home), 801/581-6765 (office), 801/581-5683 (fax), E-mail:<br />

<br />

President Elect: Gary Whitman, School of Music, Texas Christian University, P.O. Box 297500, Ed Landreth Hall,<br />

Fort Worth, TX 76129, 817/257-6622 (office), 817/257-7640 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Secretary: Kristina Belisle, School of Music, University of Akron, Akron, OH 44325-1002, 330/972-8404 (office),<br />

330/972-6409 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Treasurer: Diane Barger, School of Music, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, 120 Westbook Music Building, Lincoln, NE<br />

68588-0100, 402/472-0582 (office), 402/472-8962 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Executive Director: So Rhee, P.O. Box 1310, Lyons, CO 80540, 801/867-4336 (phone), 212/457-6124 (fax), E-mail:<br />

<br />

Editor/Publisher: James Gillespie, College of Music, University of North Texas, P.O. Box 311367, Denton, TX 76203-1367,<br />

940/565-4096 (office), 940/565-2002 (fax), E-mail: or <br />

Editorial Associates: Himie Voxman, 821 N. Linn, Iowa City, IA 52245<br />

Contributing Editor: Joan Porter, 400 West 43rd, Apt. 41L, New York, NY 10036<br />

Editorial Staff: Joseph Messenger (Editor of Reviews), Department of Music, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011,<br />

515/294-3143, E-mail: ; William Nichols (Audio Review Editor), 111 Steeplechase Circle,<br />

West Monroe, LA 71291, 318/396-8299, E-mail: ; Tsuneya Hirai, 11-9 Oidecho,<br />

Nishinomiya, 662-0036 Japan; Kalmen Opperman, 17 West 67th Street, #1 D/S, New York, NY 10023; Heston L.<br />

Wilson, M.D., 1155 Akron Street, San Diego, CA 92106, E-mail: ; Michael Webster,<br />

Shepherd School of Music, Rice University, P.O. Box 1892, Houston, TX 77251-1892, 713/838-0420 (home),<br />

713/838-0078 (fax), E-mail: ; Bruce Creditor, 11 Fisher Road, Sharon, MA 02067,<br />

E-mail: ; Thomas W. Jacobsen, 3970 Laurel Street, New Orleans, LA 70115, E-mail:<br />

; Jean-Marie Paul, Vandoren, 56 rue Lepic, F-75018 Paris, France, (33) 1 53 41 83 08 (phone),<br />

(33) 1 53 41 83 02 (fax), E-mail: ; Deborah Check Reeves, Curator of Education, National<br />

Music Museum, University of South Dakota, 414 E. Clark St., Vermillion, SD 57069; phone: 605/ 677-5306; fax:<br />

605/677-6995; Museum Web site: ; Personal Web site: ;<br />

Paul Harris, 15, Mallard Drive, Buckingham, Bucks. MK18 1GJ, U.K.; E-mail: ;<br />

Margaret Thornhill, 806 Superba Avenue, Venice, CA 90291; phone: 310/464-7653; e-mail ;<br />

personal Web site: <br />

I.C.A. Research Center: SCPA, Performing Arts Library, University of Maryland, 2511 Clarice Smith Performing<br />

Arts Center, College Park, MD 20742-1630<br />

Research Coordinator and Library Liaison: John Cipolla, Department of Music, Western Kentucky University,<br />

1906 College Heights Blvd #41029, Bowling Green, KY 41029, (S) 270/745-7093<br />

Webmaster: Kevin Jocius, Headed North, Inc. Web Design, 847/742-4730 (phone), <br />

Historian: Alan Stanek, 1352 East Lewis Street, Pocatello, ID 83201-4865, 208/232-1338 (phone), 208/282-4884 (fax),<br />

E-mail:<br />

<strong>International</strong> Liaisons:<br />

Australasia: Floyd Williams, 27 Airlie Rd, Pullenvale, Qld, Australia, (61)7 3374 2392 (phone), E-mail <br />

Europe/Mediterranean: Guido Six, Artanstraat 3, BE-8670 Oostduinkerke, Belgium, (32) 58 52 33 94 (home), (32) 59 70 70<br />

08 (office), (32) 58 51 02 94 (home fax), (32) 59 51 82 19 (office fax), E-mail: <br />

North America: Luan Mueller, 275 Old Camp Church Road, Carrollton, GA 30117, 678/796-2414 (cell), E-mail: <br />

South America: Marino Calva, Ejido Xalpa # 30 Col. Culhuacan, Mexico D.F. 04420 Coyoacan, (55) 56 95 42 10<br />

(phone/fax), (55) 91 95 85 10 (cell), E-mail: <br />

National Chairpersons:<br />

Argentina: Mariano Frogioni, Bauness 2760 4to. B, CP: 1431, Capital Federal, Argentina<br />

Armenia: Alexandr G. Manukyan, Aigestan str. 6 h. 34,Yerevan 375070, Armenia, E-mail: <br />

Australia: Floyd Williams, Queensland Conservatorium, P. O. Box 3428, Brisbane 4001, Australia; 61/7 3875 6235 (office);<br />

61/7 3374 2392 (home); 61/733740347 (fax); E-mail: <br />

Austria: Alfred Prinz, 3712 Tamarron Dr., Bloomington, Indiana 47408, U.S.A. 812/334-2226<br />

Belgium: Guido Six, Artanstraat 3, B-8670 Oostduinkerke, Belgium, 32/58 52 33 94 (home), 32 59 70 70 08 (office),<br />

Fax 32 58 51 02 94 (home), 32 59 51 82 19 (office), E-mail: <br />

Brazil: Ricardo Dourado Freire, SHIS QI 17 conj. 11 casa 02, 71.645-110 Brasília-DF, Brazil, 5561/248-1436 (phone),<br />

5561/248-2869 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Canada: vacant<br />

Eastern Canada: Stan Fisher, School of Music, Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia B0P 1XO, Canada<br />

Central Canada: Connie Gitlin, School of Music, University of Manitoba, 65 Dafoe Road, Winnipeg, MB, R3T 2N2, Phone<br />

204/797-3220, E-mail: <br />

Western Canada: Gerald N. King, School of Music, University of Victoria, Box 1700 STN CSC, Victoria, British Columbia V8W<br />

2Y2, Canada, Phone 250/721-7889, Fax 250/721-6597, E-mail: <br />

Caribbean: Kathleen Jones, Torrimar, Calle Toledo 14-1, Guaynabo, PR 00966-3105, Phone 787/782-4963,<br />

E-mail: <br />

Chile: Luis Rossi, Coquimbo 1033 #1, Santiago centro, Chile, (phone/fax) 562/222-0162, E-mail: <br />

Costa Rica: Alvaro D. Guevara-Duarte, 300 M. Este Fabrica de Hielo, Santa Cruz-Guanacaste, Costa Rica, Central America,<br />

E-mail: <br />

Czech Republic: Stepán Koutník, K haji 375/15 165 00 Praha 6, Czech Republic, E-mail: <br />

Denmark: Jørn Nielsen, Kirkevaenget 10, DK-2500 Valby, Denmark, 45-36 16 69 61 (phone),<br />

E-mail: <br />

Finland: Antti Nuorivuori, Ainonkatu 4, FL-48200 Kotka, Finland, 358 400 50 1909 (phone), 358 401 50 1909 (fax),<br />

E-mail: <br />

France: Guy Deplus, 37 Square St. Charles, Paris, France 75012, phone 33 (0) 143406540<br />

Germany: Ulrich Mehlhart, Dornholzhauser Str. 20, D-61440 Oberursel, Germany, <br />

Great Britain: David Campbell, 83, Woodwarde Road, London SE22 8UL, England, 44 (0)20 8693 5696 (phone/fax),<br />

E-mail: <br />

Greece: Paula Smith Diamandis, S. Petroula 5, Thermi 57001, Thessaloniki, Greece, E-mail: <br />

Hong Kong: Andrew Simon, Flat A2, 20th Floor, Block A, The Fortune Gardens, 11 Seymour Road, Hong Kong,<br />

(011) 852 2987 9603 (phone), E-mail , <br />

Hungary: József Balogh, Hold utca 23, Fszt. 6, 1054 Budapest, Hungary, 361 388 6689 (phone), E-mail: ,<br />

<br />

Iceland: Kjartan ‘Oskarsson, Tungata 47, IS-101, Reykjavik, Iceland, 354 552 9612 (phone), E-mail: <br />

Ireland: Tim Hanafin, Orchestral Studies Dept., DIT, Conservatory of Music, Chatham Row, Dublin 2, Ireland,<br />

353 1 4023577 (fax), 353 1 4023599 (home phone), E-mail: <br />

Israel: Eva Wasserman-Margolis, Weizman 6, Apt. 3, Givatayim, Israel 53236, E-mail: <br />

Italy: Luigi Magistrelli, Via Buonarroti 6, 20010 S. Stefano Ticino (Mi), Italy, 39/(0) 2 97 27 01 45 (phone/fax),<br />

E-mail: <br />

Japan: Koichi Hamanaka, Rm 575 9-1-7 Akasaka Minatoku, Tokyo 107-0052 Japan, 81-3-3475-2844 (phone), 81-3-3475-6417<br />

(fax), Web site: , E-mail: <br />

Korea: Im Soo Lee, Hanshin 2nd Apt., 108-302, Chamwondong Suhchoku, Seoul, Korea. (02) 533-6952 (phone),<br />

(02) 3476-6952 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Luxembourg: Marcel Lallemang, 11 Rue Michelshof, L-6251 Scheidgen, Luxembourg, E-mail: <br />

Mexico: Luis Humberto Ramos, Calz. Guadalupe I. Ramire No. 505-401 Col. San Bernadino, Xochimilco, Mexico D.F.,<br />

16030. 6768709 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands: Nancy Wierdsma-Braithwaite, Arie van de Heuvelstraat 10, 3981 CV, Bunnik, Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands, E-mail:<br />

<br />

New Zealand: Andrew Uren, 26 Appleyard Crescent, Meadowbank, Auckland 5, New Zealand,<br />

64 9 521 2663 (phone and fax).<br />

Norway: Håkon Stødle, Fogd Dreyersgt. 21, 9008 Tromsø, Norway 47/77 68 63 76 (home phone), 47/77 66 05 51 (phone,<br />

Tromsø College), 47/77 61 88 99 (fax, Tromsø College), E-mail: <br />

People’s Republic of China: Guang Ri Jin, Music Department, Central National University, No. 27 Bai Shi Qiao Road,<br />

Haidian District, Beijing, People’s Republic of China, 86/10-6893-3290 (phone)<br />

Peru: Ruben Valenzuela Alejo, Av. Alejandro Bertello 1092, Lima, Peru 01, 564-0350 or 564-0360 (phone),<br />

(51-1) 564-4123 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Poland: Krzysztof Klima, os. Wysokie 10/28, 31-819 Krakow, Poland. 48 12 648 08 82 (phone), 48 12 648 08 82 (fax),<br />

E-mail: <br />

Portugal: António Saiote, Rua 66, N. 125, 2 Dto., 4500 Espinho, Portugal, 351-2-731 0389 (phone)<br />

Slovenia: Jurij Jenko, C. Na Svetje 56 A, 61215 Medvode, Slovenia. Phone 386 61 612 477<br />

South Africa: Edouard L. Miasnikov, P.O. Box 249, Auckland Park, 2006, Johannesburg, South Africa,<br />

(011) 476-6652 (phone/fax)<br />

Spain: Carlos Jesús Casadó Tarín, Calle Bausá, 8-10, Ptal.1-2°G Madrid 28033, Spain, (00 34) 690694557 (phone),<br />

E-mail: <br />

Sweden: Kjell-Inge Stevensson, Erikssund, S-193 00 Sigtuna, Sweden<br />

Switzerland: Andreas Ramseier, Alter Markt 6, CH-3400 Burgdorf, Switzerland<br />

Taiwan: Chien-Ming, 3F, 33, Lane 120, Hsin-Min Street, Tamsui, Taipei, Taiwan 25103<br />

Thailand: Peter Goldberg, 105/7 Soi Suparat, Paholyotin 14, Phyathai, Bangkok 10400 Thailand<br />

662/616-8332 (phone) or 662/271-4256 (fax), E-mail: <br />

Uruguay: Horst G. Prentki, José Martí 3292 / 701, Montevideo, Uruguay 11300, 00598-2-709 32 01 (phone)<br />

Venezuela: Victor Salamanques, Calle Bonpland, Res. Los Arboles, Torrec Apt. C-14D, Colinas de Bello Yonte Caracas<br />

1050, Venezuela, E-mail: <br />

Betty Brockett (1936–2003)<br />

Clark Brody, Evanston, Illinois<br />

Jack Brymer (1915–2003)<br />

Larry Combs, Evanston, Illinois<br />

Guy Deplus, Paris, France<br />

Stanley Drucker, New York, New York<br />

F. Gerard Errante, Norfolk, Virginia<br />

Lee Gibson, Denton, Texas<br />

James Gillespie, Denton, Texas<br />

Paul Harvey, Twickenham, Middlesex, U.K.<br />

Stanley Hasty, Rochester, New York<br />

Ramon Kireilis, Denver, Colorado<br />

Jacques Lancelot, Paris, France<br />

Karl Leister, Berlin, Germany<br />

HONORARY MEMBERS<br />

Mitchell Lurie, Los Angeles, California<br />

John McCaw, London, England<br />

John Mohler, Chelsea, Michigan<br />

Bernard Portnoy (1915–2006)<br />

Alfred Prinz, Bloomington, Indiana<br />

Harry Rubin, York, Pennsylvania<br />

James Sauers (1921–1988)<br />

William O. Smith, Seattle, Washington<br />

Ralph Strouf (1926–2002)<br />

Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr, East Lansing, Michigan<br />

Himie Voxman, Iowa City, Iowa<br />

George Waln (1904–1999)<br />

David Weber (1914–2006)<br />

Pamela Weston, Hothfield, Kent, U.K.<br />

Commercial Advertising / General Advertising Rates<br />

RATES & SPECIFICATIONS<br />

The <strong>Clarinet</strong> is published four times a year and contains at least 48 pages printed offset on 70<br />

lb. gloss stock. Trim size is approximately 8 1/4" x 11". All pages are printed with black ink,<br />

with 4,000 to 4,500 copies printed per issue.<br />

DEADLINES FOR ARTICLES, ANNOUNCEMENTS,<br />

RECITAL PROGRAMS, ADVERTISEMENTS, ETC.<br />

Sept. 1 for Dec. issue • Dec. 1 for Mar. issue • Mar. 1 for June issue • June 1 for Sept. issue<br />

—ADVERTISING RATES —<br />

Size Picas Inches Single Issue (B/W) Color**<br />

Outside Cover* 46x60 7-5/8x10 $1,000<br />

Inside Cover* 46x60 7-5/8x10 $560 $ 855<br />

Full Page 46x60 7-5/8x10 $420 $ 690<br />

2/3 Vertical 30x60 5x10 $320 $ 550<br />

1/2 Horizontal 46x29 7-5/8x4-3/4 $240 $ 470<br />

1/3 Vertical 14x60 2-3/8x10 $200 $ 330<br />

1/3 Square 30x29 5x4-3/4 $200 $ 330<br />

1/6 Horizontal 30x13-1/2 5x2-3/8 $120 $ 230<br />

1/6 Vertical 14x29 2-3/8x4-3/4 $120 $ 230<br />

**First request honored.<br />

**A high-quality color proof, which demonstrates approved color, must accompany all color submissions. If not<br />

provided, a color proof will be created at additional cost to advertiser.<br />

NOTE: Line screen values for <strong>the</strong> magazine are 150 for black & white ads and 175 for color. If <strong>the</strong> poor quality of<br />

any ad submitted requires that it be re-typeset, additional charges may be incurred.<br />

All new ads must be submitted in an electronic format. For more information concerning this procedure,<br />

contact Executive Director So Rhee.<br />

THE INTERNATIONAL CLARINET ASSOCIATION<br />

MEMBERSHIP FEES<br />

Student: $25 (U.S. dollars)/one year; $45 (U.S. dollars)/two years<br />

Regular: $50 (U.S. dollars)/one year; $95 (U.S. dollars)/two years<br />

Institutional: $50 (U.S. dollars)/one year; $95 (U.S. dollars)/two years<br />

Payment must be made by check, money order, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, or<br />

Discover. Make checks payable to <strong>the</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> <strong>Association</strong> in U.S. dollars.<br />

Please use <strong>International</strong> Money Order or check drawn on U.S. bank only. Send payment to:<br />

The <strong>International</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> <strong>Association</strong>, So Rhee, P.O. Box 1310, Lyons, CO 80540 USA.<br />

© Copyright 2007, INTERNATIONAL CLARINET ASSOCIATION<br />

ISSN 0361-5553 All Rights Reserved<br />

Published quarterly by <strong>the</strong> INTERNATIONAL CLARINET ASSOCIATION<br />

Designed and printed by BUCHANAN VISUAL COMMUNICATIONS – Dallas, Texas U.S.A.<br />

Views expressed by <strong>the</strong> writers and reviewers in The <strong>Clarinet</strong> are not necessarily those of <strong>the</strong> staff of <strong>the</strong> journal or of <strong>the</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

September 2007 Page 3

By a strange coincidence my current<br />

issue of The <strong>Clarinet</strong> arrived<br />

on <strong>the</strong> same day as an e-mail from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Editor of <strong>Clarinet</strong> and Saxophone, <strong>the</strong><br />

CASS magazine, asking if I knew <strong>the</strong><br />

where<strong>about</strong>s of Uncle Paul, who used to<br />

write a problem page in <strong>the</strong> early days of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> & Saxophone Society of<br />

Great Britain. I believe that <strong>the</strong> Mystery<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>ist pictured on p. 30 [in <strong>the</strong> June<br />

issue] is none o<strong>the</strong>r than he, now known<br />

as Great Uncle Paul. He became embittered<br />

by <strong>the</strong> lack of recognition he<br />

received for his revolutionary <strong>the</strong>ories on<br />

<strong>the</strong> consistency of cork grease, and went<br />

to live on a kibbutz in Israel. A significant<br />

clue is his telephone number, 999, written<br />

on <strong>the</strong> side of his hut. I understand that<br />

Helen Pearse plans to fly to Israel to interview<br />

this venerable clarinetist.<br />

— Paul Harvey<br />

September 2007 Page 5

Example 1<br />

A<br />

B<br />

C<br />

D<br />

by Michael Webster<br />

Rose Sperrazza<br />

Michael Webster<br />

HOW DRY AM I<br />

Thirty-eighth in a series of articles using<br />

excerpts from a clarinet method in progress<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Professor of <strong>Clarinet</strong> at Rice University’s<br />

Shepherd School of Music.<br />

Sometimes you get lucky. After<br />

seven years of tonguing incorrectly<br />

I went to Aspen, where Earl Bates<br />

(1920–1991; See The <strong>Clarinet</strong> 18/3,<br />

May/June 1991 for Henry Gulick’s tribute)<br />

taught me how to tongue “tip-to-tip”<br />

correctly. A year later, I matriculated at<br />

Eastman and found Stanley Hasty’s approach<br />

to be identical.<br />

Mr. Bates drew diagrams of two types<br />

of tone, in which <strong>the</strong> height represented<br />

dynamic and <strong>the</strong> width represented duration<br />

(see Example 1).<br />

Page 6<br />

A and B represent sustained air tonguing,<br />

tenuto and staccato. C and D represent<br />

notes that are tapered by <strong>the</strong> breath, C<br />

without silence and D with silence. When<br />

<strong>the</strong> sound stops abruptly, as in B, <strong>the</strong> style<br />

is called dry (secco in Italian, sec in<br />

French). There doesn’t seem to be a universally<br />

accepted term for C and D, so I<br />

call C wet and D moist. Both are versions<br />

of an articulation often indicated with dots<br />

and a slur, called legato-staccato. A is<br />

sometimes called legato tongue, but I prefer<br />

to call it tenuto (indicated by dashes<br />

over each note), reserving legato for<br />

slurred notes. With Mr. Bates I learned<br />

how to play dryly, sustaining <strong>the</strong> air while<br />

stopping notes with <strong>the</strong> tongue.<br />

Mr. Hasty used two signs to indicate<br />

A and B, placed between notes, as in<br />

Example 2.<br />

B, a deep V shape, is called a clip, and<br />

A is a plus that he didn’t give a name to,<br />

so let’s call it a non-clip. In general, <strong>the</strong><br />

clip is used to shorten <strong>the</strong> last note of a<br />

slur in preparation for staccato, whereas<br />

<strong>the</strong> non-clip is used between slurs and is<br />

identical to tenuto tongue. After a clip,<br />

<strong>the</strong> tongue stays on <strong>the</strong> reed for a short<br />

time, whereas as it bounces off <strong>the</strong> reed<br />

immediately after a non-clip. All of<br />

Hasty’s undergrads were given a diet of<br />

Klosé and Rose, laden with clips and<br />

non-clips, and <strong>the</strong> explanation that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

seem like exaggerations in practice but<br />

Example 2<br />

THE CLARINET<br />

sound normal and natural when performed<br />

at speed.<br />

Students will have better success with<br />

Rose studies if <strong>the</strong>y have a strongly<br />

developed sense of how and when to clip<br />

or not to clip, starting at <strong>the</strong> intermediate<br />

level. Speed is important, because clipping<br />

at a slow tempo can indeed conjure<br />

up images of <strong>the</strong> Sahara. So <strong>the</strong>se examples<br />

are all at a tempo that is fast enough<br />

for clipping to be viable, but slow enough<br />

for <strong>the</strong> intermediate student.<br />

The Ländler by Schubert (Example 2)<br />

must be fast enough to have <strong>the</strong> characteristic<br />

lilt of this Austrian dance, a slow<br />

waltz also favored by Brahms and Mahler,<br />

among o<strong>the</strong>rs. Measure 1 demonstrates <strong>the</strong><br />

easiest way to approach <strong>the</strong> non-clip, via<br />

repeated notes that do not require coordination<br />

of finger and tongue. Crossing <strong>the</strong><br />

bar line into m. 2 is an exception to <strong>the</strong><br />

general rule of clipping to prepare staccato<br />

notes. Here <strong>the</strong> need to lead to <strong>the</strong> emphasized<br />

downbeat of <strong>the</strong> Ländler supersedes<br />

<strong>the</strong> usual practice. The first clip comes in<br />

m. 7, followed by several more (mm. 9,<br />

10, 12, 13, 14).<br />

In our zeal to practice clips and nonclips<br />

let’s not forget to make music! For<br />

example, <strong>the</strong> breath can emphasize each<br />

downbeat to impart <strong>the</strong> characteristic<br />

feeling of one beat per bar in a Ländler,<br />

with <strong>the</strong> even-numbered bars having<br />

more emphasis than <strong>the</strong> odd-numbered.<br />

The quarter notes in mm. 2, 4, and 6

CALL FOR<br />

PROPOSALS<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>Fest® 2008<br />

Kansas City,<br />

Missouri, USA<br />

July 2–6, 2008<br />

2008 will <strong>Clarinet</strong>Fest®<br />

take place on <strong>the</strong> campus<br />

of <strong>the</strong> University<br />

of Missouri–Kansas<br />

City. Co-sponsored by <strong>the</strong> UMKC<br />

Conservatory of Music and Dance,<br />

<strong>the</strong> conference takes place in <strong>the</strong><br />

heart of Kansas City, <strong>the</strong> city with<br />

more fountains than any o<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

Rome and second to only Paris in<br />

number of boulevards. The campus<br />

is very close to <strong>the</strong> Plaza restaurant<br />

and shopping district, modeled after<br />

historic Seville, Spain.<br />

If you are interested in sending<br />

in a presentation proposal, please<br />

download and complete <strong>the</strong> Callfor-Proposals<br />

Application Form<br />

from and send<br />

to <strong>the</strong> address below. Recordings<br />

and written requests will be accepted<br />

through September 1, 2007 and<br />

will be reviewed by <strong>the</strong> committee.<br />

Jane Carl, Artistic Director<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>Fest® 2008<br />

University of Missouri–Kansas City<br />

Conservatory of Music and Dance<br />

4949 Cherry<br />

Kansas City, MO 64110<br />

<br />

September 2007 Page 7

www.music.uiuc.edu<br />

Example 3<br />

KARL KRAMER, DIRECTOR<br />

• Consistently ranked among <strong>the</strong><br />

best American music schools<br />

• <strong>International</strong>ly renowned faculty<br />

• Numerous financial awards<br />

• Thousands of successful alumni<br />

• Excellent facilities<br />

VARIETY OF ACADEMIC<br />

PROGRAMS<br />

Bachelor’s, Master’s, and<br />

Doctoral degrees<br />

ARTIST<br />

FACULTY<br />

Page 8<br />

For more information, please contact:<br />

Music Admissions Office<br />

Phone: 217-244-7899<br />

E-mail: musadm@music.uiuc.edu<br />

J. David Harris<br />

clarinet<br />

John Dee<br />

oboe<br />

Jonathan Keeble<br />

flute<br />

Timothy McGovern<br />

bassoon<br />

Debra Richtmeyer<br />

saxophone<br />

Accredited institutional member of <strong>the</strong> National<br />

<strong>Association</strong> of Schools of Music since 1933.<br />

should be tapered with <strong>the</strong> breath, as in<br />

Example 1, C or D. There is also room<br />

for variety in <strong>the</strong> length and style of <strong>the</strong><br />

staccato notes and clips.<br />

I like Carmine Campione’s conception<br />

of articulated notes having five possible<br />

lengths between <strong>the</strong> longest tenuto and<br />

<strong>the</strong> shortest staccato. One can practice<br />

any of <strong>the</strong>se examples using all five, but<br />

<strong>the</strong> most stylish option here would be<br />

number 4, medium short. One should<br />

also experiment with <strong>the</strong> firm, hard,<br />

pointed tongue tip; lightness of touch on<br />

<strong>the</strong> reed; and lateral placement between<br />

<strong>the</strong> center and corner of <strong>the</strong> reed. Ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than stopping <strong>the</strong> sound too abruptly,<br />

allowing <strong>the</strong> reed to have <strong>the</strong> tiniest<br />

“echo” due to lightness or lateral placement<br />

of <strong>the</strong> tongue can render a nice<br />

pizzicato-like quality: short but resonant.<br />

This menu allows you to have your cake<br />

THE CLARINET<br />

and eat it too, with a wine that is dry but<br />

not too dry!<br />

The Handel Pièce pour le Clavecin is<br />

a bit more complicated and difficult. The<br />

first four measures have typical clips<br />

ending each two-note slur. Measure 5 is<br />

also typical: four non-clips. Unlike <strong>the</strong><br />

Ländler, this offers an opportunity to<br />

practice coordinating fingers and tongue<br />

during non-clips. The second note of m.<br />

6 could be clipped or not, depending on<br />

personal preference. I think it sounds better<br />

not clipped, continuing <strong>the</strong> sequence<br />

of <strong>the</strong> previous four. The 16th notes do<br />

not influence <strong>the</strong> clipping of B ♭ at <strong>the</strong> end<br />

of <strong>the</strong> third beat. I choose not to clip at<br />

<strong>the</strong> barline of m. 10 for <strong>the</strong> same reason<br />

as in m. 6. The three-note slur, often<br />

favored by Heinrich Baermann in his<br />

articulation of Weber, should also be<br />

clipped, as in m. 18.

Example 4<br />

Example 5<br />

No clarinet method would be complete<br />

without <strong>the</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> Polka. It is fun<br />

to play and also pedagogically rich, containing<br />

arpeggio study on <strong>the</strong> tonic triad<br />

and dominant seventh, short trills, fast<br />

triplets, “moist” quarters, clips and nonclips.<br />

It is also a very good means of<br />

gaining speed in mixed articulations.<br />

There are non-clips at <strong>the</strong> first double bar<br />

and in mm. 11, 14, and 15 and clips in<br />

mm. 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13, 16, and 17.<br />

Meanwhile, <strong>the</strong> repeated quarters (mm. 2,<br />

6, 10, and 18) demonstrate how clips and<br />

non-clips don’t work well at slower<br />

speeds. These quarters must be tapered or<br />

stopped with <strong>the</strong> air to achieve a joyful<br />

bounce without dryness. The trills can be<br />

two finger wiggles, single inverted mordents,<br />

or omitted, depending upon <strong>the</strong><br />

ability of <strong>the</strong> individual student.<br />

Finally we have a sample of <strong>the</strong> rich<br />

pedagogical repertoire for piano by one<br />

of <strong>the</strong> best composers for children,<br />

Robert Schumann. His works for piano<br />

solo (e.g. Kinderszenen, Op. 15; Album<br />

für die Jugend, Op. 67) and piano duet<br />

(e.g. 12 Vierhändige Klavierstücke für<br />

kleine und grosse Kinder, Op. 85;<br />

Kinderball, Op. 130) contain dozens and<br />

dozens of musical pictures that are richly<br />

varied in mood and expression, sophisticated<br />

but easy to play. Many of <strong>the</strong>m are<br />

adaptable for clarinet, and The Wild<br />

Horseman (Example 5) is one of my<br />

favorites. It offers <strong>the</strong> budding pianist<br />

staccato practice in both hands, and <strong>the</strong><br />

clarinetist <strong>the</strong> same staccato practice in<br />

both registers. A short staccato (number<br />

4 or 5 on <strong>the</strong> Campione length scale)<br />

with exaggerated clips is appropriate for<br />

<strong>the</strong> fast clip clop of hooves, <strong>the</strong> sforzandi<br />

adding to <strong>the</strong> drama. Don’t miss <strong>the</strong><br />

chance to point out how <strong>the</strong> melody outlines<br />

tonic and dominant triads in D<br />

minor and B ♭ major.<br />

Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> repertoire is Mozart,<br />

Weber, Brahms, Muczynski, or Stockhausen,<br />

mastering <strong>the</strong> art of clipping is essential<br />

to becoming a fine clarinetist. For most<br />

people, clip art is a child of <strong>the</strong> Internet,<br />

but for clarinetists, clip art goes back to<br />

Anton Stadler and beyond. By mastering<br />

<strong>the</strong> art of <strong>the</strong> clip and non-clip, a clarinetist<br />

can answer <strong>the</strong> question “How dry am I”<br />

confidently: “Just as dry as <strong>the</strong> musical<br />

style dictates.”<br />

WEBSTER’S WEB<br />

Your feedback and input are valuable to<br />

our readership. Please send comments and<br />

questions to Webster’s Web at or Michael Webster, Shepherd<br />

School of Music, MS-532, P.O. Box<br />

1892, Houston TX 77251-1892; fax 713-<br />

348-5317; Web site . Jim Gillespie and I are still<br />

interested in receiving articles <strong>about</strong> teaching<br />

beginning or younger clarinetists to<br />

supplement my current articles, which<br />

September 2007 Page 9

have reached <strong>the</strong> intermediate student<br />

level. Such articles may be sent directly to<br />

Webster’s Web.<br />

In response to <strong>the</strong> articles <strong>about</strong> yoga and<br />

<strong>the</strong> clarinet, I received <strong>the</strong> following letter<br />

from Josh Mietz, an ultramarathoning clarinetist<br />

who lives is Missoula, MT, where he<br />

is a GTA for <strong>the</strong> University of Montana:<br />

First I would like to thank and<br />

congratulate you on your recent articles.<br />

Your discussion of our physical<br />

selves and how awareness through<br />

yoga can nurture that is much needed,<br />

I feel.<br />

Second, I’d like to suggest two<br />

books. While I’m not an MD, I studied<br />

massage <strong>the</strong>rapy (CMT) between<br />

my degrees in clarinet performance.<br />

Ra<strong>the</strong>r than taking <strong>the</strong> usual route of<br />

working on clients full time, I opted<br />

to teach cadaver-based anatomy and<br />

was involved in many dissections<br />

and presented lectures based on that<br />

work. While <strong>the</strong> Netter’s was certainly<br />

a reference for location, we<br />

used <strong>the</strong>se books as a means of elaborating<br />

on various functions associated<br />

with <strong>the</strong> anatomy presented.<br />

The first, Anatomy of Hatha<br />

Yoga by H. David Coulter, has an<br />

amazing description of respiration<br />

and includes fascinating data regarding<br />

<strong>the</strong> autonomic nervous system<br />

and various lung capacities. It<br />

also goes into great detail <strong>about</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

function of <strong>the</strong> anatomy during each<br />

of <strong>the</strong> yoga poses. The second book<br />

is Anatomy Trains by Thomas W.<br />

Myers. This relates somewhat to <strong>the</strong><br />

breathing issues but more specifically<br />

to postural anatomy. There are<br />

discussions of various instrumentalists<br />

(sadly <strong>the</strong> clarinet is not one, but<br />

<strong>the</strong> trumpet comes close) as well as<br />

athletes. This book takes a holistic<br />

approach to our bodies and how, for<br />

example, a hypertrophic muscle in<br />

our back may be affecting something<br />

in our leg or arm. The opposite<br />

can also be true that something<br />

in your leg may be affecting something<br />

in your neck. You may also<br />

find, as I did, as a runner, that this<br />

book will make you rethink some of<br />

your training patterns as well as<br />

clarinet practice habits.<br />

I hope this information helps.<br />

They are great references.<br />

All <strong>the</strong> best,<br />

Josh Mietz<br />

My comment:<br />

I purchased both books, and have had<br />

an opportunity only to skim <strong>the</strong>m so far.<br />

Both are handsomely presented, profusely<br />

illustrated, and very detailed in approaching<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir subject matter. The first is specifically<br />

geared toward <strong>the</strong> yoga practitioner,<br />

while <strong>the</strong> second deals with a fascinating<br />

aspect of general anatomy. I am really looking<br />

forward to reading <strong>the</strong>m in more detail.<br />

The <strong>Clarinet</strong><br />

PUBLICATION SCHEDULE<br />

The magazine is usually<br />

mailed during <strong>the</strong> last week of<br />

February, May, August and November.<br />

Delivery time within<br />

North America is normally<br />

10–14 days, while airmail<br />

delivery time outside of North<br />

America is 7–10 days.<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Dayat THE BOSTON CONSERVATORY<br />

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2007<br />

9 A.M.–10 P.M.<br />

ACTIVITIES:<br />

MASTERCLASSES, VENDOR EXHIBITS,<br />

PRESENTATIONS, EVENING CONCERT<br />

MEET THE ARTISTS:<br />

TOM MARTIN (BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA),<br />

MICHAEL NORSWORTHY, JONATHAN COHLER,<br />

IAN GREITZER (BOSTON POPS), AND OTHERS<br />

Join us in Boston this fall for a day devoted<br />

to <strong>the</strong> clarinet and an evening concert by<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> country’s top artists.<br />

Try new clarinets, mouthpieces, reeds, and<br />

equipment; attend public masterclasses;<br />

and experience all that <strong>the</strong> Boston clarinet<br />

community has to offer. All ages and ability<br />

levels are welcome.<br />

VENDORS:<br />

BUFFET CRAMPON, YAMAHA, BACKUN MUSICAL, ORSI & WEIR,<br />

CONN/SELMER, RICO REEDS, VANDOREN, CLARK FOBES,<br />

GARY GORCZYCA REPAIRS, AND MANY OTHERS.<br />

REGISTRATION FEE: $30<br />

Michael Norsworthy<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Faculty<br />

Director, <strong>Clarinet</strong> Day at<br />

The Boston Conservatory<br />

8 The Fenway<br />

Boston, MA 02215<br />

www.bostonconservatory.edu<br />

Please vistit www.michaelnorsworthy.com/clarinetday for registration details and masterclass participation.<br />

Or call (617) 912-9124 or email mnorsworthy@bostonconservatory.edu<br />

Page 10<br />

THE CLARINET

2007 Harold Wright<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Merit Award<br />

Yuan Gao<br />

Since its inception in 2003, The<br />

Boston Woodwind Society<br />

(BWWS) grants yearly merit awards<br />

to honor <strong>the</strong> artistry and achievements of<br />

five legendary woodwind musicians,<br />

including clarinetist Harold Wright. The<br />

recipient of <strong>the</strong> 2007 Harold Wright<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Merit Award is Yuan Gao. Mr.<br />

Gao is currently a student of Jonathan<br />

Cohler at The Longy School of Music in<br />

Cambridge, MA, where he is an Artist<br />

Diploma candidate. At <strong>the</strong> age of 16, Mr.<br />

Gao won First Prize at <strong>the</strong> Second National<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Competition of China, and a<br />

year later was <strong>the</strong> top prizewinner at <strong>the</strong><br />

Jeunesses Musicales competition in Romania.<br />

As a member of Trio Diamante<br />

(clarinet, violin and piano), Mr. Gao was a<br />

First Prize winner at <strong>the</strong> 2006 <strong>International</strong><br />

Chamber Music Ensemble Competition<br />

(sponsored by <strong>the</strong> Chamber Music Foundation<br />

of New England) and a quarterfinalist<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Fischoff National Chamber Music<br />

Competition. In June 2007, Mr. Gao participated<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>International</strong> Woodwind<br />

Festival in Boston, performing in masterclasses<br />

led by Jessica Phillips and<br />

Valdemar Rodriguez.<br />

To learn more <strong>about</strong> <strong>the</strong> BWWS merit<br />

awards, visit <strong>the</strong>ir Web site at<br />

.<br />

“G. Mensi” <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Competition of<br />

Breno, Italy<br />

A Report by Luigi Magistrelli<br />

The fifth edition of <strong>the</strong> Breno<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> Competition<br />

“G. Mensi” took place on May<br />

10–12, 2007. Breno is a nice little town<br />

in <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn part of Italy where<br />

Giacomo Mensi was born. He was a talented<br />

clarinetist who studied at <strong>the</strong> local<br />

Conservatory in Darfo Boario Terme,<br />

and <strong>the</strong>n later took a diploma at <strong>the</strong><br />

Hochschule of Freiburg (Germany)<br />

studying with <strong>the</strong> well-known player<br />

Dieter Klöcker. Soon after his graduation<br />

he died in a tragic car accident. This<br />

competition has been organized in order<br />

to keep alive <strong>the</strong> memory of this young<br />

player. In <strong>the</strong> competition <strong>the</strong> clarinetists<br />

could compete in three different categories:<br />

“young promises” Category A (up<br />

to 13 years old) and B (ages 14–17) and<br />

“excellence.” The president of <strong>the</strong> jury in<br />

<strong>the</strong> major category was Wenzel Fuchs of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. The<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r members of <strong>the</strong> jury were Luigi<br />

Magistrelli, Nicola Miorada, Primo<br />

Borali and Silvio Maggioni, who was<br />

also <strong>the</strong> organizer and Artistic Director of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Competition.<br />

A good number of participants arrived<br />

from Italy and o<strong>the</strong>r European countries.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> “young promises” division <strong>the</strong><br />

winners ex-aequo of Category A were<br />

Stefano Borghi from Modena (Italy) and<br />

Kalin Kante Aliaz from Slovenia who<br />

each won 100 Euros. Second prize went<br />

to Stefano Martinelli from Vercelli<br />

(Italy) who won 150 Euros, and third<br />

prize to Filip Rusnov from Croatia, who<br />

won 100 Euros. Special mention was<br />

made to Marco Laffranchini from Darfo<br />

Boario Terme (Italy). In <strong>the</strong> Category B<br />

first prize was awarded to Andrea Fallico<br />

CORRECTION<br />

In Rose Sperrazza’s Master<br />

Class article in <strong>the</strong> June 2007 issue<br />

(Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 6,8), <strong>the</strong> musical<br />

examples were reversed by mistake.<br />

Figure 1 should be Figure 2,<br />

and vice versa. We apologize for<br />

<strong>the</strong> mistake and for any confusion it<br />

may have caused.<br />

—James Gillespie, Editor<br />

(l to r) prize winners: Manuela Vettori, Antonio Piemonte, Rumy Balazs, Igor Armani,<br />

Giampiero Pezzucchi (Breno city administration) and members of <strong>the</strong> jury: Primo<br />

Borali, Wenzel Fuchs, Nicola Miorada (behind) Luigi Magistrelli and Silvio Maggioni<br />

September 2007 Page 11

from Bronte who won 300 Euros, (Italy),<br />

second prize ex-aequo to Calogero Presti<br />

from Caltanisetta (Italy) and to Daniele<br />

Zamboni from Darfo Boario Terme who<br />

each won 100 Euros. Third prize exaequo<br />

went to Fabio Maini from San<br />

Giovanni Bianco (Italy) and to Damiano<br />

Pè from Darfo Boario Terme (Italy) who<br />

each won 75 Euros. Special mention<br />

went to Fabrizio Alessandrini from Roccafranca<br />

(Italy) and Gioele Rudari from<br />

Desenzano, (Italy).<br />

In <strong>the</strong> first round of <strong>the</strong> “Excellence”<br />

category <strong>the</strong> compulsory pieces were <strong>the</strong><br />

Weber Concerto No. 1, Op. 73 and a<br />

modern and interesting piece, Elegy for<br />

Danny by Ciro Scarponi, an Italian clarinetist<br />

who recently died. In <strong>the</strong> second<br />

round 11 players out of 35 were passed<br />

on to <strong>the</strong> next round where <strong>the</strong>y had to<br />

play <strong>the</strong> Stravinski 3 Pieces and <strong>the</strong><br />

Mozart Concerto. Five players were<br />

selected for <strong>the</strong> last round, where <strong>the</strong> last<br />

two movements of <strong>the</strong> Weber Op. 73<br />

were chosen as <strong>the</strong> required repertoire.<br />

The winner was <strong>the</strong> Hungarian Balazs<br />

Rumy, who received 2,000 Euros and <strong>the</strong><br />

opportunity to perform <strong>the</strong> Weber<br />

Concerto, Op 73 and Elegy for Danny<br />

with <strong>the</strong> Vivaldi Chamber Orchestra,<br />

conducted by Silvio Maggioni, <strong>the</strong> day<br />

after <strong>the</strong> conclusion of <strong>the</strong> competition.<br />

Second prize and 350 Euros each was<br />

given to Igor Armani (Trento, Italy) and<br />

Antonio Piemonte (Regalbuto, Italy) and<br />

third prize to Manuela Vettori (Trento,<br />

Italy) who received 300 Euros. Special<br />

mention went to Maria Francesca Latella<br />

(Lamantea, Italy).<br />

Karl Leister Master Classes<br />

On World Wide Web<br />

On April 25, 2007, German clarinetist<br />

Karl Leister presented a<br />

two-hour master class at Northwestern<br />

University to an enthusiastic<br />

group of student and professional players.<br />

The class was streamed live over <strong>the</strong><br />

World Wide Web. Two evenings later<br />

Herr Leister presented an expressive performance<br />

of music by Mendelssohn,<br />

Schumann, Schubert and Beethoven. The<br />

event was arranged and hosted by Northwestern<br />

University faculty clarinetist<br />

Steve Cohen.<br />

Capitol <strong>Clarinet</strong> Choir<br />

On May 6, 2007, <strong>the</strong> Capitol <strong>Clarinet</strong><br />

Choir, consisting of Washington,<br />

D.C.’s finest professional<br />

clarinetists, performed its first concert at<br />

St. Andrew’s United Methodist Church<br />

and Day School in Annapolis, Maryland.<br />

Ben Redwine, Artistic Director for <strong>the</strong> St.<br />

Andrew’s Concert Series (),<br />

organized <strong>the</strong> concert as<br />

<strong>the</strong> finale for <strong>the</strong> series’ inaugural season.<br />

Works performed were Samuel Barber’s<br />

Adagio for Strings, Peter Schickele’s<br />

Monochrome III, John Stephen’s Nocturne,<br />

Percy Aldridge Grainger’s No. 5 Irish Tune<br />

From County Derry, arr. Maurice Saylor<br />

and Walking Music, arr. Scott Farquhar,<br />

John Stephen’s Nonette, <strong>the</strong> world premiere<br />

of Maurice Saylor’s Three Fits from <strong>the</strong><br />

Hunting of <strong>the</strong> Snark, Robert Roden’s A<br />

Difference of Opinion, and <strong>the</strong> world premiere<br />

of Tune Takes a Trip, by Henry<br />

Cowell. Maurice Saylor and Ben Redwine<br />

traveled to <strong>the</strong> Library of Congress, where<br />

Henry Cowell’s works are catalogued. The<br />

never before performed work, written in<br />

1948 by one of America’s preeminent composers,<br />

was copied and engraved for this<br />

premiere performance by Ben and Maurice.<br />

Third <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Competition<br />

“Saverio Mercadante’<br />

The Third <strong>International</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong><br />

Compettion “Severio Mercadante” will be<br />

held in Noci (Bari), Italy, October 11–14,<br />

2007. Fabio di Casola will serve as<br />

Chairman for <strong>the</strong> Competition. There are<br />

three categories: senior soloists (born after<br />

1972), junior soloist (born after 1989) and<br />

chamber music (with clarinet from duo to<br />

sextet; contestants born after 1972).<br />

For more information and competition<br />

rules, consult <strong>the</strong> Web site: .<br />

Back Issues<br />

of The <strong>Clarinet</strong><br />

Back-issue order forms for The<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> may now be downloaded<br />

from <strong>the</strong> I.C.A. Web site: . Copies may also be<br />

requested by contacting:<br />

James Gillespie<br />

College of Music<br />

University of North Texas<br />

P.O. Box 311367<br />

Denton, TX 76203-1367<br />

E-mail: <br />

Karl Leister instructs Northwestern student<br />

Michael Rezzo.<br />

Page 12<br />

(left to right) Ben Redwine, Sheila Buck, Carl Long, Dawn Henry, Lori Fowser, conductor<br />

John Stephens, Jim Hurd, Paul Skinner, Sam Chin, Maurice Saylor, and percussionist<br />

Greg Herron. Seated, from left to right: Scott Farquhar and Darin Thiriot.<br />

THE CLARINET

y William Nichols<br />

Awelcome new addition to this<br />

writer’s library is a release on <strong>the</strong><br />

Phaedra label, a disc which is volume<br />

45 in <strong>the</strong> Phaedra series of Belgian<br />

music entitled In Flanders’ Fields. It presents<br />

two large works by composer, pianist<br />

and conductor Piet Swerts: <strong>the</strong> String<br />

Quartet No. 2 of 1998, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong><br />

Quintet of 2001. The Belgian clarinetist<br />

Roeland Hendrikx joins <strong>the</strong> Tempera<br />

String Quartet of Finland in <strong>the</strong> quintet.<br />

The quartet is performed by <strong>the</strong> Spiegel<br />

String Quartet.<br />

This release is an effective chamber<br />

music experience which spans a wide<br />

emotional range and presents accessible<br />

and engaging music. The production<br />

notes justifiably state that “Piet Swert’s<br />

music succeeds splendidly in building a<br />

bridge between tradition and our own<br />

time. His warm, passionate and highly<br />

lyrical language charms everyone into an<br />

intense experience of <strong>the</strong> whole range of<br />

human feelings.” Swerts, now in his mid-<br />

40s, is an accomplished composer with<br />

more than 200 works to his credit.<br />

The <strong>Clarinet</strong> Quintet is a five-movement<br />

work of 32+ minutes and is a significant<br />

contribution to <strong>the</strong> repertoire.<br />

The clarinet is treated for <strong>the</strong> most part as<br />

an important but not dominating voice.<br />

The harmonic language is that of a contemporary<br />

tonal style, and traditional<br />

structural forms are at work here. There<br />

is a serene beauty present in much of this<br />

quintet and a stylistic intensity reminiscent<br />

of Shostakovich. The second movement,<br />

“Notturno,” and fourth movement,<br />

“Elegia,” are <strong>the</strong> longest sections, occupying<br />

more than half <strong>the</strong> quintet’s duration,<br />

and are seemingly <strong>the</strong> focal points<br />

of <strong>the</strong> work. The “Elegia” is a simple<br />

piece which is mesmerizing, and in its<br />

unique timeless way, remindful of <strong>the</strong><br />

“Air” from Bach’s D-major orchestral<br />

suite. The two slow movements are separated<br />

by a satirical “Scherzo” which<br />

again hearkens somewhat to Shostakovich<br />

and even includes a quote from Johann<br />

Strauss. The quintet finale is a rondo<br />

of moderately fast tempo which features<br />

<strong>the</strong> different voices of <strong>the</strong> ensemble and<br />

presents <strong>the</strong> clarinet in a more virtuosic<br />

manner than previously heard.<br />

The performance by Roeland Hendrikx<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Tempera Quartet is exquisitely<br />

warm and committed. Hendrikx is <strong>the</strong><br />

principal clarinetist of <strong>the</strong> Belgian<br />

National Orchestra and has demonstrated<br />

a devotion to <strong>the</strong> cause of Belgian music.<br />

He possesses a lovely, round tone, and his<br />

smooth facility is heard to great affect in<br />

this recording, especially in <strong>the</strong> quintet’s<br />

finale. The recorded sound is very good,<br />

transparent in texture, and well balanced,<br />

even if <strong>the</strong> string quartet work has a bit<br />

more sonic impact than that of <strong>the</strong> quintet.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> Quintet will be of<br />

more interest to our readers, <strong>the</strong> String<br />

Quartet No. 2 is also enthusiastically recommended.<br />

The work is interesting,<br />

Van Cott Information<br />

Services, Inc.<br />

See our full catalog of woodwind<br />

books, music, and CDs at:<br />

http://www.vcisinc.com<br />

Shipping (Media Mail-U.S.): $4.50<br />

for <strong>the</strong> first item, $.50 for each<br />

additional. Priority and Overseas<br />

Air Mail also available.<br />

We accept purchase orders from<br />

US Universities.<br />

email: info@vcisinc.com<br />

P.O. Box 9569<br />

Las Vegas, NV 89191, USA<br />

(702) 438-2102<br />

Fax (801) 650-1719<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Music<br />

Arnold Bass Cl Scale Book ....... $19.95<br />

Brahms Cl Sonatas [Henle]........ $29.95<br />

Brahms Cl Trio [Henle] ............. $32.95<br />

Messiean Qrt. For End of Time.. $44.95<br />

Mozart Cl Conc. K622 [Baer.] .. $20.95<br />

Mozart Cl Quintet K581 [Baer.] $18.95<br />

Neilsen Cl Conc. [W Hanson] ... $36.95<br />

Bernstein “Riffs” ....................... $16.95<br />

Viktor’s Tale Cl Pn (J. Williams) $14.95<br />

Music 750+ & CDs 200+<br />

strongly dramatic, and varied in content.<br />

This disc in its entirety makes for wonderful<br />

listening experiences from first<br />

hearing to subsequent hearings. Piet<br />

Swert’s musicality as demonstrated in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Quintet, and <strong>the</strong> piece’s playability,<br />

should make this a strong programming<br />

possibility for a clarinetist<br />

looking for a new clarinet/string quintet.<br />

The production is well annotated with<br />

photographs and notes in four languages.<br />

The release is PHAEDRA 92045, and <strong>the</strong><br />

Web site is: . This<br />

music is available for order from <strong>the</strong> Phaedra<br />

Web site as a CD, or also as a download. The<br />

disc is also available through <strong>the</strong> artist’s Web<br />

site at: .<br />

* * * * *<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r disc featuring compositions by<br />

one composer has come my way, this time a<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Books<br />

32 Rose Studies: Analysis & Study Guide (Larsen) $29.95<br />

Advanced Intonation Tech w/CD (J.Gibson) ....... $29.95<br />

Bass <strong>Clarinet</strong> [Method] (Volta) ............................ $44.95<br />

Daniel Bonade (Kycia) ........................................ $35.95<br />

The Daniel Bonade Workbook (Guy) .................. $24.95<br />

Baroque <strong>Clarinet</strong> (Rice) ...................................... $34.95<br />

Campione on <strong>Clarinet</strong> (Campione) ...................... $44.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> (Brymer) ................................................ $19.95<br />

The <strong>Clarinet</strong> Doctor (Klug) .................................. $34.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Fingerings (Ridenour)............................. $19.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>ist’s Guide to Klezmer (Puwalski) ............ $24.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>ist’s Notebook Vol. 1 (Schmidt)............... $29.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>ist’s Notebook Vol. 2 (Schmidt)............... $16.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>ist’s Notebook Vol. 3 (Schmidt)............... $14.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong>ist’s Notebook Vol. 4 (Schmidt)............... $14.95<br />

The <strong>Clarinet</strong> Revealed (Ferron) ............................ $29.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Concerto in Outline (Heim) .............. $24.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Literature in Outline (Heim) .................. $24.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Secrets (Gingras)[Revised Ed.]................. $34.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Sonata in Outline (Heim) [New Printing] $24.95<br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> Virtuosi of <strong>the</strong> Past (Weston) .................. $38.95<br />

More <strong>Clarinet</strong> Virtuosi of <strong>the</strong> Past (Weston) ......... $38.95<br />

Yesterday’s <strong>Clarinet</strong>tists: A Sequel (Weston) ........ $38.95<br />

Educators Guide to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> (Ridenour).......... $46.95<br />

Embouchure Building (Guy) ............................... $14.95<br />

Hand & Finger Development (Guy) ................. $24.95<br />

HB for Making and Adj. Sngl. Reeds (Opperman) $19.95<br />

Mozart Forgeries (Leeson) .................................. $19.95<br />

Orchestral Studies for <strong>the</strong> Eb Cl (Hadcock) .......... $21.95<br />

Orchestral Musician’s Library CD-ROM [each] ... $19.95<br />

(Vols 1-8() with discounts on 3 or more)<br />

Symphonic Rep. Bass Cl Vols 1-3 (Drapkin) ea. $21.95<br />

The Working <strong>Clarinet</strong>ist (Hadcock)...................... $39.95<br />

September 2007 Page 13

2006 release from Centaur Records featuring<br />

three concertos by Rudolf Haken.<br />

Professor Haken is a violist and active<br />

orchestra, chamber music, new music, and<br />

solo performer, and chairs <strong>the</strong> string division<br />

of <strong>the</strong> University of Illinois School of<br />

Music. He was a member of <strong>the</strong> Houston<br />

Symphony and Houston Grand Opera<br />

Orchestra, he has participated in summer<br />

festivals, and has presented master classes<br />

internationally. In addition to concertizing<br />

in North and South America and in Europe,<br />

he has done extensive study of piano and<br />

composition. Information <strong>about</strong> his compositions<br />

and recordings can be found on his<br />

Web site: .<br />

The three concertos programmed on<br />

this disc are <strong>the</strong> Concerto for Five-String<br />

Viola, <strong>the</strong> Oboe Concerto, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong><br />

Concerto. The soloists are Haken, Nancy<br />

Ambrose King, and William King, respectively.<br />

In each case <strong>the</strong> accompanying<br />

ensembles are not of traditional orchestral<br />

instrumentation, however <strong>the</strong>y are all conducted<br />

by Julien Benichou.<br />

Just a quick perusal of <strong>the</strong> accompanying<br />

ensemble for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Clarinet</strong> Concerto is a<br />

tip off that this not a traditional concerto:<br />

piccolo, oboe, clarinet, bass clarinet, soprano<br />

saxophone, contrabassoon, horn, trumpet,<br />

trombone, tuba, marimba, tom-toms,<br />

vibes, cymbal, two lead steel pans, snare,<br />

two double second pans, cello pan, triangle,<br />

bass pan, tam-tam, 1st violins, 2nd<br />

violins, violas, cellos, and six-string electric<br />

bass. The piece is dedicated to <strong>the</strong><br />

soloist, William King.<br />

The steel drums are used to good<br />

effect, primarily in <strong>the</strong> opening of <strong>the</strong><br />

concerto and in a return of <strong>the</strong> opening<br />

material, and mark <strong>the</strong> first time this listener<br />

has encountered steel pans used in<br />

an orchestral context, and in a large form<br />

(a 25-minute solo work). The movement<br />

is based on <strong>the</strong> four-note B(B ♭ )ACH(B)<br />

pitch motive used by a number of composers<br />

in past works. The motive serves<br />

as a basis for a calypso-inspired steel<br />

Visit <strong>the</strong> <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>Clarinet</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

on <strong>the</strong> World Wide Web:<br />

www.clarinet.org<br />

Page 14<br />

band tune, which is infectious and happy,<br />

and every bit of what one would expect<br />

from a Caribbean steel band. The movement<br />

is a bit raucous and jazzy in its<br />

BACH variations, with a hint along <strong>the</strong><br />

way of Kurt Weill. Surprisingly it closes<br />

with a solo tuba leading to <strong>the</strong> slow<br />

movement, which is based on <strong>the</strong> threenote<br />

motive ACH. This lyrical section<br />

features several solo instruments in addition<br />

to <strong>the</strong> clarinet. In addition to marimba<br />

and vibraphone <strong>the</strong> steel pans are<br />

effectively used. The last movement is<br />

described by <strong>the</strong> composer as opening<br />

with a CH motive, <strong>the</strong> second half of <strong>the</strong><br />

BACH motive, from which develops a<br />

raucous tune in triple meter, which alternates<br />

throughout with an expansive, lyrical<br />

melody. The concerto culminates in a<br />

bombastic climax, featuring an epic battle<br />

between <strong>the</strong> two <strong>the</strong>mes. The movement<br />

is at times tongue-in-cheek, perhaps<br />

a satirical polacca, and exhibits a keen<br />

scoring imagination. This exciting trip<br />

ends brilliantly.<br />

The performance by William King is<br />

first-rate in every way. Dr. King is an<br />

experienced player who has played with<br />

several major American orchestra, festival<br />

orchestras, chamber orchestras, opera<br />

and ballet orchestras, as well as making<br />

solo appearances. He is on <strong>the</strong> faculty of<br />

Oakland University in Rochester,<br />

Michigan. He possesses a full, vibrant<br />

tone, crisp articulation and smooth technique.<br />

He plays this concerto with complete<br />

mastery, which is demonstrated<br />

throughout, with special praise for <strong>the</strong> last<br />

movement. The ensembles in all three<br />

works under Julien Benichou are precise,<br />

well balanced and exciting in <strong>the</strong>ir at times<br />

somewhat unusual role.<br />

All of <strong>the</strong> music on this disc was<br />

recorded in 2002 at <strong>the</strong> Krannert Center at<br />

<strong>the</strong> University of Illinois. The recording is<br />

sonically excellent, beautifully balanced,<br />

and quite transparent, even when <strong>the</strong> musical<br />

textures get thick. Kudos to engineer<br />

Jon Schoenoff for capturing so strikingly<br />

this sometimes problematic music.<br />

This disc is highly recommended not<br />

only for <strong>the</strong> clarinet work, but also for<br />

Haken’s exuberant Americana fiddling<br />

style of <strong>the</strong> viola work and <strong>the</strong> beautiful<br />

and engaging Oboe Concerto, so wonderfully<br />

played by Nancy Ambrose King.<br />

Haken’s music is both original and derivative,<br />

well crafted, and a joy to experience.<br />

This is a winner — guaranteed to<br />

bring a smile to your face.<br />

THE CLARINET<br />

The recording is CENTAUR CRC 2826<br />

and is available at retail outlets and from <strong>the</strong><br />

label Web site: .<br />

* * * * *<br />

Apologies are due <strong>the</strong> members of<br />

Trio Lignum and to David Osenberg of<br />

Classiquest for only now making known<br />

to our readers a really terrific recording<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Hungarian label BMC, received in<br />

2005. The release entitled Offertorium<br />

presents this outstanding ensemble consisting<br />

of Csaba Klenyán and Lajos<br />

Rozmán (clarinets and bass clarinets) and<br />

bassoonist György Lakatos. Fortunately<br />

<strong>the</strong> recording is still available and Trio<br />

Lignum has also released a later disc<br />

entitled Dream Drawing, which I hope<br />

will come my way soon.<br />

The programming concept is remarkable,<br />

and a straight-through listening of <strong>the</strong><br />

15 tracks of this 66 minutes of music flies<br />

by. The contents are early music from <strong>the</strong><br />

Middle Ages and Renaissance (plus a<br />

piece from a Bach pupil), contrasted with<br />

late 20th-century and 21st-century works.<br />

The pieces are intermingled in an order<br />

that effectively works, and includes trio<br />

pieces from early masters Machaut,<br />

Landini, Desprez, Ockeghem, Byrd, and<br />

John Bull. The modern works are: Chromatic<br />

Game (1999) and Five Repeated<br />

(1985) by László Sáry; Gegen (2003) and<br />

Der Richter (1999) by Ádám Kondor;<br />

Quand j’étais jeune, on me disait (1994)<br />

by Zoltán Jeney; Berçeuse canonique<br />

(1993) by László Vidovszky; and Verba<br />

Mea (2002) by András Soós. The Bach<br />

pupil’s piece mentioned above was transcribed<br />

in 2000 by Ádám Kondor and<br />

given <strong>the</strong> title A Musical Labyrinth.<br />

The performances of <strong>the</strong>se early works<br />

on modern instruments would win over<br />

even die hard purists. There is a purity of<br />

tuning and serenity of sound offered by<br />

this ensemble which is rarely heard. These<br />

early pieces are without exception a joy to<br />

hear and will perhaps give some readers<br />

ideas <strong>about</strong> <strong>the</strong> viability of Medieval and<br />

Renaissance music for this instrumentation.<br />

Trio Lignum’s performances are<br />

appropriately reverent when called for and<br />

in keeping with <strong>the</strong> CD’s title. Also appropriate<br />

is <strong>the</strong> idea of beginning and ending<br />

<strong>the</strong> disc with Guillaume de Machaut’s<br />

rondeaux, “My end is my beginning and<br />

my beginning my end,” presented I<br />

believe as two different recording takes.

The prelude-like keyboard piece by one of<br />

Bach’s pupils is somewhat daring and<br />

stunningly beautiful as presented here in<br />

this modern transcription.<br />

The modern repertoire is engaging and<br />

demonstrates <strong>the</strong> ensemble’s control of<br />

tone color, intonation, rhythmic security<br />

and technical skills, which are of a very<br />

high level. The music also showcases <strong>the</strong><br />

surprisingly wide range of colors available<br />

to only three instruments. Ádám<br />

Kondor’s Gegen is a dissonant and dramatic<br />

piece which amply displays <strong>the</strong><br />

ensemble’s virtuosic skills. It is very<br />

angular, at times frantic, and at times utilizes<br />

microtonal writing. It is scored for<br />

bass clarinet in place of <strong>the</strong> second clarinet,<br />

and creates some striking sounds.<br />

This exciting piece is in memory of<br />

Xenakis whose fingerprint is present.<br />

Also by Kondor is Der Richter which<br />

uses two bass clarinets. The trio is joined<br />

here by vocalist Zoltán Mizsei in one of<br />

<strong>the</strong> most intriguing pieces on <strong>the</strong> disc.<br />

The text is based on a story from a novel<br />

by Adam Seide on an unjust death sentence<br />

issued in <strong>the</strong> last years of <strong>the</strong> Nazi<br />

regime. The two-bass clarinets and bassoon<br />

scoring makes for some dark and<br />

dramatic elements. The piece stylistically<br />

brings to mind Schönberg’s A Survivor<br />

from Warsaw.<br />

Two pieces by László Sáry, Chromatic<br />

Game and Five Repeated are simple pieces<br />

using kaleidoscopic effects created by<br />

rhythmic and melodic cells (perhaps á la<br />

Steve Reich). The Vidovsky Berçeuse Canonique<br />

is a fascinating three-part canon and<br />

is a transcription of a piano piece. Verba<br />

Mea of András Soós is influenced in concept<br />

by Renaissance choral music based on<br />

letter codes. The performers read a text<br />

silently and build <strong>the</strong> piece based on <strong>the</strong><br />

inner rhythm and articulation of <strong>the</strong> text. In<br />

practice this becomes a piece more linked<br />

to <strong>the</strong> performers than <strong>the</strong> composer.<br />

Throughout <strong>the</strong> whole of this disc we<br />

hear a gorgeous, dark woody sound from<br />

<strong>the</strong>se instrumentalists, blending perfectly in<br />

all aspects. This music cannot be played<br />

any better. Indeed <strong>the</strong>re are not too many<br />

choices of recordings of music for two clarinets<br />

and bassoon to be had, but Trio Lignum’s<br />

Offertorium is <strong>the</strong> best one known<br />

to this writer. The sonic palette is gorgeous.<br />

Strongly recommended, this release is<br />

BMC CD 090, and is available from <strong>the</strong><br />

BMC Web site: . The<br />

e-mail address is: .<br />

Good listening!<br />

PHOTO: CHIANEN YEN<br />

Be<strong>the</strong> instrument<br />

DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC AND PERFORMING ARTS PROFESSIONS<br />

Instrumental Performance | B.M., M.A., Ph.D.<br />

Study with acclaimed artists in <strong>the</strong> performing arts<br />

capital of <strong>the</strong> world—New York City.<br />

Selected Woodwind Faculty<br />

CLARINET Stanley Drucker, Pascual Martinez Forteza, Larry Guy,<br />

David Krakauer, Es<strong>the</strong>r Lamneck<br />

BASS CLARINET Dennis Smylie<br />

SAXOPHONE Paul Cohen, Tim Ruedeman<br />

WOODWIND ENSEMBLES IN RESIDENCE<br />

New Hudson Saxophone Quartet, Quintet of <strong>the</strong> Americas<br />

Scholarships and fellowships available.<br />

Pursue your goals. Be <strong>the</strong> instrument. Be NYU Steinhardt.<br />

Visit www.steinhardt.nyu.edu/clarinet2008<br />

or call 212 998 5424<br />

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY IS AN AFFIRMATIVE ACTION/EQUAL OPPORTUNITY INSTITUTION.<br />

September 2007 Page 15

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA —<br />

LINCOLN’S 11TH ANNUAL<br />

MIDWEST CLARIFEST<br />

A review by Kristen Denny<br />

The 11th annual Midwest ClariFest,<br />