Phrase structure 2: Arguments and Adjuncts

Phrase structure 2: Arguments and Adjuncts

Phrase structure 2: Arguments and Adjuncts

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

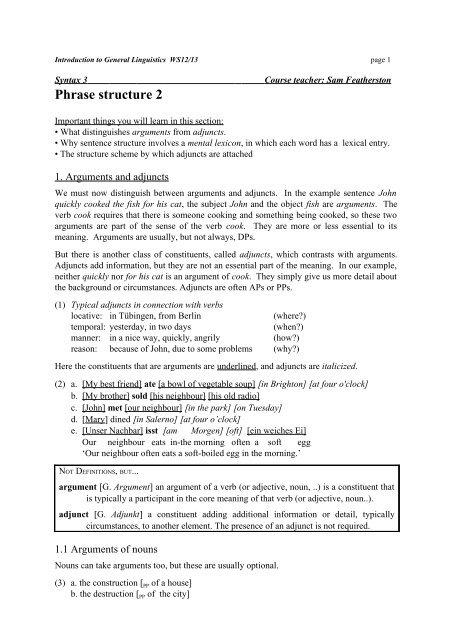

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13 page 1<br />

Syntax 3<br />

<strong>Phrase</strong> <strong>structure</strong> 2<br />

Course teacher: Sam Featherston<br />

Important things you will learn in this section:<br />

• What distinguishes arguments from adjuncts.<br />

• Why sentence <strong>structure</strong> involves a mental lexicon, in which each word has a lexical entry.<br />

• The <strong>structure</strong> scheme by which adjuncts are attached<br />

1. <strong>Arguments</strong> <strong>and</strong> adjuncts<br />

We must now distinguish between arguments <strong>and</strong> adjuncts. In the example sentence John<br />

quickly cooked the fish for his cat, the subject John <strong>and</strong> the object fish are arguments. The<br />

verb cook requires that there is someone cooking <strong>and</strong> something being cooked, so these two<br />

arguments are part of the sense of the verb cook. They are more or less essential to its<br />

meaning. <strong>Arguments</strong> are usually, but not always, DPs.<br />

But there is another class of constituents, called adjuncts, which contrasts with arguments.<br />

<strong>Adjuncts</strong> add information, but they are not an essential part of the meaning. In our example,<br />

neither quickly nor for his cat is an argument of cook. They simply give us more detail about<br />

the background or circumstances. <strong>Adjuncts</strong> are often APs or PPs.<br />

(1) Typical adjuncts in connection with verbs<br />

locative: in Tübingen, from Berlin (where?)<br />

temporal: yesterday, in two days (when?)<br />

manner: in a nice way, quickly, angrily (how?)<br />

reason: because of John, due to some problems (why?)<br />

Here the constituents that are arguments are underlined, <strong>and</strong> adjuncts are italicized.<br />

(2) a. [My best friend] ate [a bowl of vegetable soup] [in Brighton] [at four o'clock]<br />

b. [My brother] sold [his neighbour] [his old radio]<br />

c. [John] met [our neighbour] [in the park] [on Tuesday]<br />

d. [Mary] dined [in Salerno] [at four o’clock]<br />

e. [Unser Nachbar] isst [am Morgen] [oft] [ein weiches Ei]<br />

Our neighbour eats in-the morning often a soft egg<br />

‘Our neighbour often eats a soft-boiled egg in the morning.’<br />

NOT DEFINITIONS, BUT...<br />

argument [G. Argument] an argument of a verb (or adjective, noun, ..) is a constituent that<br />

is typically a participant in the core meaning of that verb (or adjective, noun..).<br />

adjunct [G. Adjunkt] a constituent adding additional information or detail, typically<br />

circumstances, to another element. The presence of an adjunct is not required.<br />

1.1 <strong>Arguments</strong> of nouns<br />

Nouns can take arguments too, but these are usually optional.<br />

(3) a. the construction [ PP of a house]<br />

b. the destruction [ PP of the city]

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13 page 2<br />

Such PPs with nouns are classified as arguments because when they are left out, there is a<br />

sense in which they are understood to be present, in the same way as they are with a verb.<br />

Nouns relating to verbs can often have a reading as a process or a reading as a result. So the<br />

process construction (= the constructing) is always the construction of something.<br />

Construction with a process meaning thus works the same way as the verb construct, with<br />

arguments. The result construction (= a building) has no arguments, because this is a result,<br />

not a process.)<br />

Nouns which are related to transitive verbs will often take arguments. Nouns which mean<br />

things which are a part of a relationship often take arguments too.<br />

(4) a. the student (of literature) (cf to study literature)<br />

b. the painter (of this picture) (cf paint a picture)<br />

c. the daughter (of Dorothea Brooke) (being a daughter is a relationship)<br />

d. the side (of the house) (a side is a part relative to a whole)<br />

Notice that there are also adjuncts that go with nouns. These also often have the form of a PP.<br />

(5) a. the daughter of Mary Anne Evans [ PP from her first marriage]<br />

b. the student of literature [ PP in Tübingen]<br />

1.2 Typical features of arguments<br />

Obligatoriness: <strong>Arguments</strong> are often obligatory: eg devour needs a direct object.<br />

(6) a. The werewolf devoured the rabbit. Der Werwolf verschlang das Kaninchen.<br />

b.*The werewolf devoured. *Der Werwolf verschlang.<br />

However this test must be applied with some care: arguments are not always obligatory. For<br />

example, eat may st<strong>and</strong> with or without an object. The absence of a constituent does not<br />

mean it is an adjunct; it may just be understood. If we say Bella was eating, it is clear that<br />

Bella was eating something, even if we don’t say what. We can’t eat nothing. So:<br />

(7) Bella was eating nothing<br />

means "Bella wasn't eating". On the other h<strong>and</strong>, (8) is meaningless.<br />

(8) *Bella was sleeping something<br />

Uniqueness: an argument can be realized by one constituent, but not by two, or by none.<br />

(9) a. [My sister] is sleeping.<br />

b.* [my sister] [my brother] is/are sleeping.<br />

c.* Is sleeping.<br />

On the other h<strong>and</strong>, there can be many adjuncts with a given verb or noun:<br />

(10)a. Edward slept [in the park] [at noon] [on Tuesday].<br />

b. The destruction of the city [in the 13th century] [after a long battle]<br />

c. an [uninhabited] [big] [white] house [near the beach]

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13 page 3<br />

Category: <strong>Arguments</strong> are often DPs, but not always. We can tell that the PP in (10) is an<br />

argument of the verb put. The verb put requires a place for the direct object to be put.<br />

<strong>Arguments</strong> may be required to be of a particular category. This is not so of adjuncts.<br />

(11)a. *Mary put the book requires [ PP on the table]<br />

b. *Jacob lived requires [ PP in Bruchsal]<br />

c. *George looked/felt requires [ AP happy, stupid, embarassed]<br />

Word order: In English, an object normally st<strong>and</strong>s next to its verb. If there is an adjunct, it<br />

will follow the argument. We cannot usually put the adjunct between the verb <strong>and</strong> its object.<br />

This tendency exists across languages, but other factors affect the order too, so it may not be<br />

clear in every language.<br />

(12)a. John read [a book] [in the garden]<br />

V argument adjunct<br />

b.*John read [in the garden] [a book]<br />

V adjunct argument<br />

(13)a. John saw [Mary] [in the cafeteria] [on Tuesday]<br />

b.*John saw [in the cafeteria] [Mary] [on Tuesday]<br />

c.* John saw [in the cafeteria] [on Tuesday] [Mary]<br />

The same effect can be observed with nouns.<br />

(14)a. a student [of linguistics] [in Tübingen]<br />

b.*a student [in Tübingen] [of linguistics]<br />

(15)a. the daughter [of Mary] [from her first marriage]<br />

b.*the daughter [from her first marriage] [of Mary]<br />

2 <strong>Arguments</strong> <strong>and</strong> the mental lexicon<br />

Words <strong>and</strong> rules: Linguistic <strong>structure</strong>s must obey general rules in a theory of grammar, but<br />

they must also reflect the properties of individual words. For example, we saw earlier that<br />

English nouns can take PP complements but not DP complements, unlike verbs which can<br />

take DP arguments. This is a rule, it applies to all nouns.<br />

However there are also important restrictions that come from individual lexical items (ie<br />

words). The arguments that a lexical item requires are specific to itself.<br />

<strong>Arguments</strong> in lexical entries: The verb see takes a DP direct object, while the verb look<br />

takes a PP object. These are located in the mental lexicon. For example, the mental lexical<br />

entry of put contains (at least) this information:<br />

(16)Lexical entry of put:<br />

a. grammatical category: V<br />

b. pronunciation: [pʊt]<br />

c. argument <strong>structure</strong>: <br />

When you learn a word, what information do you memorize with it? Part of this information<br />

will be its required or optional arguments.

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13 page 4<br />

<strong>Arguments</strong> are the constituents that occur in the argument <strong>structure</strong> of the lexical entry.<br />

<strong>Adjuncts</strong> do not occur in the lexical entry.<br />

(17) I put my mobile phone into my pocket last night to keep it safe.<br />

The constituents [I], [my mobile phone], <strong>and</strong> [into my pocket] are arguments, since they<br />

represent in the argument <strong>structure</strong> of put. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, [last night]<br />

<strong>and</strong> [to keep it safe] are adjuncts, <strong>and</strong> thus do not appear in the argument <strong>structure</strong> of put.<br />

2.1 The notation of argument <strong>structure</strong><br />

<strong>Arguments</strong> appear in . Subjects get extra angled brackets: , or <br />

(18)Lexical entry of put:<br />

a. grammatical category: V<br />

b. pronunciation: [pʊt]<br />

c. argument <strong>structure</strong>: <br />

Category type: For internal arguments the category is always specified: .<br />

Technically speaking, we do not need to specify that the subject must be a DP. Subjects are<br />

always DP. It would be more economical to let external rules specify this. Lexical entries<br />

are for word-specific idiosyncratic information, that which is not included in the rules. This<br />

should be as little as possible, since rules are, in terms of mental effort, cheap, <strong>and</strong> wordspecific<br />

information is expensive, that is, requires more effort.<br />

(19) Argument <strong>structure</strong> of put<br />

< X1, < DP2, PP3 >><br />

|<br />

external arg. internal arguments<br />

| |<br />

tells the grammar that tells the grammar that these will be<br />

this will be the subject objects, with categories DP <strong>and</strong> PP<br />

Here, however, we shall mark subjects as DP, since they are DP.<br />

Round brackets: Optional arguments can be marked with round brackets:<br />

devour: with an obligatory object,<br />

eat: with an optional object.

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13 page 5<br />

3 The syntactic representation of arguments<br />

A verb or noun combines with its arguments, creating a phrase (VP, NP, ...). The details in<br />

the lexical entry specify what arguments are necessary.<br />

The argument <strong>structure</strong> in the lexical entry projects into the syntactic <strong>structure</strong>. The<br />

requirements on all arguments must be satisfied as sisters to the head.<br />

(22) a. verb with one object b. verb with two objects<br />

VP VP<br />

V DP2 V DP2 PP3 | |<br />

read a book put a book on the table<br />

lexical<br />

entry: ategory: V category: V<br />

arg.-struc.: arg.-struc.: <br />

... ...<br />

c. noun with one argument d. verb with no object e. noun with no argument<br />

NP VP NP<br />

N PP V N<br />

| | |<br />

neighbor of Mary sleep house<br />

lexical<br />

entry category: N category: V category: N<br />

arg.-struc.: < > arg.-struc.: > …<br />

... …<br />

We therefore find the following <strong>structure</strong>s:<br />

(23)a. verb with one object b. verb with two objects<br />

VP VP<br />

V DP V DP PP<br />

| |<br />

read a book put a book on the table<br />

c. noun with one argument d. verb with no object e. noun with no argument<br />

NP VP NP<br />

N PP V N<br />

| | |<br />

neighbour of Mary sleep house<br />

Remember: Since arguments are requirements of the head, they must be attached as sisters<br />

to the head X. They are thus daughters of the the phrasal projection of the head XP.

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13 page 6<br />

4 The syntactic representation of adjuncts<br />

The difference between arguments <strong>and</strong> adjuncts in the <strong>structure</strong> is illustrated here:<br />

(24)a. <strong>structure</strong> for arguments b. <strong>structure</strong> for adjuncts<br />

XP XP<br />

X YP XP ZP<br />

argument adjunct<br />

<strong>Arguments</strong> are sisters to X, a word, <strong>and</strong> daughters to XP, the mother of X. Since adjuncts<br />

are optional, there is no fixed position for them. <strong>Adjuncts</strong> are sisters to XP <strong>and</strong> daughter to a<br />

higher XP. We have to generate this additional phrasal projection above the existing<br />

phrasal projection XP.<br />

(26) a. adjunct to an NP with an argument b. adjunct to an NP with no argument<br />

NP new! NP new!<br />

NP PP NP PP<br />

|<br />

N PP from Gascony N with a camera<br />

| (adjunct) | (adjunct)<br />

king of France tourist<br />

c. adjunct to a VP with one argument d. adjunct to a VP with no argument<br />

VP new! VP new!<br />

VP PP VP PP<br />

|<br />

V DP in the garden V during the show<br />

| (adjunct) | (adjunct)<br />

read a book sleep<br />

This difference between arguments <strong>and</strong> adjuncts makes sense in terms of the lexical entry:<br />

the specification from the lexical entry of a word X drives the addition of sisters to the word<br />

level category X. <strong>Adjuncts</strong> are not projected by the argument <strong>structure</strong>, they are added on<br />

the outside, so to speak, on a new outer layer.<br />

(27) a. <strong>structure</strong> for arguments b. <strong>structure</strong> for adjuncts<br />

XP XP<br />

X YP XP YP<br />

lexical argument adjunct<br />

entry:<br />

category: X<br />

arg.struc.: …YP

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13 page 7<br />

This explains why several adjuncts can be stacked. The addition of each adjunct causes the<br />

addition of a new highest phrasal node. We can do this again <strong>and</strong> again (<strong>and</strong> again.....).<br />

(28) a. b. c. VP<br />

VP VP PP<br />

VP VP PP VP PP at noon<br />

| | |<br />

V V in the park V in the park<br />

| | |<br />

slept slept slept<br />

This structural difference between arguments <strong>and</strong> adjuncts explains the difference in wordorder<br />

that we saw above. We can build a <strong>structure</strong> of a verb plus complement plus adjunct:<br />

(29) VP<br />

VP PP<br />

V DP in the garden<br />

| (adjunct)<br />

read a book<br />

The argument DP is sister to the V <strong>and</strong> daughter of VP. The adjunct PP is sister to VP <strong>and</strong><br />

daughter of VP . Fine.<br />

If we add the adjunct first, it becomes sister of VP, daughter of a new VP. If we want to add<br />

an argument after this, there is no attachment position which is both after the adjunct <strong>and</strong> still<br />

sister to V. The argument can therefore not be attached outside the adjunct.<br />

(30) a. you can add an adjunct … b. … but you can’t add an argument outside<br />

VP<br />

VP VP DP<br />

VP PP VP PP a book<br />

| |<br />

V in the garden V in the garden<br />

| (adjunct) | (adjunct)<br />

read read

Introduction to General Linguistics WS12/13 page 8<br />

Exercises syntax 3 – <strong>Arguments</strong> <strong>and</strong> adjuncts.<br />

1a. How many arguments do the following verbs have?<br />

yawn, write, send, lend, kill, grow, kick, hop, bet, marry (two possibilities), die, rain, show,<br />

introduce (people)<br />

1b. And these nouns?<br />

boss, garden, growth, neighbour, loan, tree, uncle, front, phone, kick, cover<br />

2. Identify the arguments <strong>and</strong> adjuncts in these examples. Draw trees.<br />

a. cook some pasta run quickly listen to the music<br />

arrive at my home sing in the choir fax a report to the ministry<br />

b. the husb<strong>and</strong> of my friend the politician from the capital<br />

the government of the country a picture of an apple<br />

c. ride a bicycle in the country drive a car carelessly<br />

buy an ice cream for a child w<strong>and</strong>er in the afternoon along the Neckar<br />

see the detective with a telescope the author of this book<br />

3. Distinguish adjuncts <strong>and</strong> arguments <strong>and</strong> draw trees for the following:<br />

see the sea<br />

the brother of the prince<br />

(to) eat some chips with your fingers<br />

sleep on the sofa<br />

prepare the lunch in the kitchen<br />

write carefully on the card<br />

watch the television<br />

the queen of the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s on her throne<br />

listen to the radio in the morning.<br />

describe my theory with some examples<br />

leave the town for a while<br />

a letter from my brother<br />

a statue of the bishop of this province<br />

a photo of my cousin from the south<br />

4. das Meer sehen klar sehen<br />

the sea see clearly see<br />

mit diesen Essstäbchen den Reis essen<br />

with these chopsticks the rice eat<br />

die abblätternde Bemalung der Mauer<br />

the peeling.off painting of.the wall