Hansa cocking plant - Stiftung Industriedenkmalpflege und ...

Hansa cocking plant - Stiftung Industriedenkmalpflege und ...

Hansa cocking plant - Stiftung Industriedenkmalpflege und ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

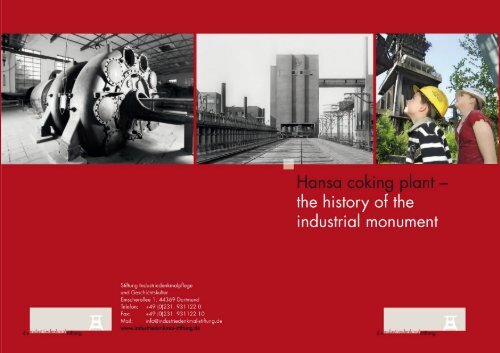

<strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> –<br />

the history of the<br />

industrial monument

Index<br />

Welcome to the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>.................................. 4<br />

<strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> –<br />

the history of the industrial monument<br />

In the beginning was the colliery............................................................ 6<br />

Merging for rationalisation.................................................................... 9<br />

Working hand in hand – the integrated production process..................... 10<br />

The birth of the central <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>............................................ 13<br />

Customised expansion –<br />

production planning and conception .................................................... 14<br />

Rearmament and expansion ................................................................ 17<br />

The end – and a truly monumental new beginning .. 20<br />

Good times .................................................................................... 22<br />

Clever planning ................................................................................ 25<br />

New paths ....................................................................................... 26<br />

Roof gardens on the coking ovens ....................................................... 28<br />

Rain collectors and cloud makers ........................................................ 30<br />

An extra curricular place of learning .................................................... 32<br />

The art lab ........................................................................................ 34<br />

A well-preserved monument ................................................................ 37<br />

From coal to coke –<br />

a trip through the production process in a coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

What is a coking <strong>plant</strong> – a brief introduction ......................................... 40<br />

The path of coal<br />

Delivery ............................................................................................ 42<br />

The coke oven battery ........................................................................ 43<br />

The coke pusher engines and the quenching wagons ............................. 45<br />

The quenching tower .......................................................................... 45<br />

The path of gas<br />

Drawing off the crude gas .................................................................. 47<br />

Producing the by-products tar and phenol.............................................. 47<br />

Ammonia, hydrogen sulphide and benzene .......................................... 48<br />

Compressing and cooling ................................................................... 50<br />

Chronicle ................................................................................... 52<br />

Further reading ....................................................................... 55<br />

Site plan ..................................................................................... 56<br />

Imprint<br />

2<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

INDEX 3

The <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> amongst the trees. Photo: 2008<br />

Welcome<br />

to the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> industrial monument has been winning over the<br />

hearts of visitors since it opened in 1999. Every year thousands of people<br />

take the opportunity to explore the “gigantic sculpture” along the Nature and<br />

Technology Adventure Trail. At the end of the 1990s people thought that list -<br />

ing a coking <strong>plant</strong> and preserving it for posterity was a somewhat audacious<br />

proposition, but today this is almost taken for granted. That said, it was only<br />

made possible after a long planning process, and the commitment of the<br />

State of North-Rhine Westphalia, the RAG company and above all the current<br />

owners of the coking <strong>plant</strong>, the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the Preservation of Industrial<br />

Monuments and Historical Culture. Here, local people and politicians also<br />

deserve a special mention for their steadfast commitment to ensuring the<br />

preservation of the industrial monument. The advocates of preservation did<br />

not always meet with approval and for a long time there were loud demands<br />

to demolish the coking <strong>plant</strong>. Happily these times are long past. “<strong>Hansa</strong>” is<br />

now an established part of the cultural landscape and interest in the coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong> is continually rising, both from visitors and users alike.<br />

The Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the Preservation of Industrial Monuments and Historical<br />

Culture is responsible for preserving the building substance of the industrial<br />

monument, conducting research into the monument, making it accessible to the<br />

general public and putting it to new uses. It places great value on presenting<br />

the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> by means of tailor-made guided tours for the general<br />

public, not forgetting particular target groups like children, young people and<br />

families, and even specialists like conservationists, historians, landscape<br />

planners, architects, photographers and engineers. Strolling through the industrial<br />

monuments has proved its worth time and time again because only then<br />

can individuals literally have a step-by-step appreciation of the dimensions<br />

and production capacities of the coking <strong>plant</strong> over and above the bare statistics<br />

in tons and cubic metres. Anyone who has ever walked through a bunker<br />

with a capacity of 4,000 tons of coal, stood in front of one of the original<br />

314 coke ovens, and seen a compressor in action, returns home not only with<br />

a rich treasury of knowledge about the history and importance of the coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong>, but also with some powerful images in their heads. After completing<br />

a tour of the site visitors are always demanding more information in order<br />

to deepen their knowledge and impressions, or simply to take home some<br />

warm memories of their visit to the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>.<br />

We are delighted to do something to satisfy this need in the form of the<br />

present brochure, and wish you a pleasant read!<br />

The staff of the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the Preservation of Industrial Monuments<br />

and Historical Culture<br />

Ursula Mehrfeld<br />

Business head<br />

dieindustriedenkmalstiftung<br />

4 HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

WELCOME TO THE HANSA COKING PLANT<br />

5

<strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> –<br />

the history of the<br />

industrial monument<br />

In the beginning was the colliery<br />

Both the name “<strong>Hansa</strong>” and the later “Hanseatic history” came about as a<br />

result of mergers. Coal was discovered as early as 1810 during drilling work<br />

on fountains in the then village of Huckarde. In 1856 the chief mining officer<br />

Wilhelm von Hövel sold his prospecting licence to the Dortm<strong>und</strong> Mining and<br />

Ironworks company, which then merged the mining field in Huckarde with<br />

those in Wischlingen and Rahm <strong>und</strong>er a new name: <strong>Hansa</strong>. The name referred<br />

to the mediaeval Hanseatic League, an international economic and<br />

trading alliance, and was intended to symbolise hopes for a business upturn<br />

in the then rural region. Some time later work began on sinking a shaft for<br />

the <strong>Hansa</strong> colliery. Coal was first brought to the surface here in 1869.<br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> colliery ca. 1890. At the time the 84 meter chimney stack on<br />

the boiler house was the highest chimney stack in the Ruhr region.<br />

A good quarter of a century later, in 1895, the <strong>plant</strong> experienced a crucial<br />

modification. The industrial tycoon Friedrich Grillo now owned the majority<br />

of shares in the company and decided to expand the works with the addition<br />

of a small colliery coking <strong>plant</strong>, south of today’s Lindberghstrasse. This was<br />

where the first “<strong>Hansa</strong> coke“ was produced. At first the <strong>plant</strong> contained more<br />

than sixty coke ovens, and after it was expanded in 1905 production rose to<br />

aro<strong>und</strong> 96,000 tons of coke per year. The coking <strong>plant</strong> site remained in<br />

operation for a total of 30 years.<br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> colliery in 1898 with the so-called “Weyhe” shaft (the<br />

Malakov tower on the left in the picture, taken out of operation as<br />

early as 1859), shaft 1 and shaft 2 and the coal washing <strong>plant</strong>.<br />

6<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE COLLIERY<br />

7

Merging for rationalisation<br />

After the First World War there was a major upheaval in the coal and steel<br />

industries in the Ruhrgebiet. Following the model of large-scale industries in<br />

the United States, German companies made plans to stimulate the economy<br />

by mergers and rationalisation. The upshot was that, in 1926, the four major<br />

coal and steel companies – the Rheinelbe-Union, the Thyssen Group, the<br />

Phoenix Group and the Rhineland Steelworks – merged to become the United<br />

Steelworks Company. The new concern comprised aro<strong>und</strong> one h<strong>und</strong>red<br />

collieries, coking <strong>plant</strong>s and steelworks, and now rose to become the second<br />

largest steel concern in the world, thereby preparing the way for technical<br />

improvements and, most importantly, an up-to-date integrated business<br />

concern.<br />

Coking <strong>plant</strong>s were an important factor in the integrated system. Until then<br />

most of the small coking <strong>plant</strong>s on the colliery sites belonging to the United<br />

Steelworks were out-of-date and unprofitable. For this reason seventeen new<br />

major coking <strong>plant</strong>s were built in the Ruhrgebiet between 1926 and 1929.<br />

From now on they were responsible for providing more than half the total of<br />

coke produced in the Ruhrgebiet.<br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> colliery in 1911 with the gatehouses containing the tag checker’s<br />

office and the accident room. On the right, the warehouse building.<br />

8 HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

MERGING FOR RATIONALISATION 9

Working hand in hand – the integrated production process<br />

The most important technical precondition for running central coking <strong>plant</strong>s<br />

in an integrated production process was the presence of integrated coking<br />

ovens. They were more efficient than earlier ovens because they could not<br />

only be fired by rich gas – for example their own purified coking <strong>plant</strong> gas –<br />

but also by blast furnace gas. This meant that large quantities of high-value<br />

coking <strong>plant</strong> gas became available for use in casting and rolling mills. In<br />

return the blast furnace gas produced in the steelworks could be sent back<br />

to the coking <strong>plant</strong> to fire the ovens. The result was an integrated system of<br />

gas supplies between the coking <strong>plant</strong>s and their associated steelworks.<br />

The overhead pipelines used to conduct the gas were to remain one of the<br />

typical urban images in the Ruhrgebiet for years.<br />

Alongside its uses in the steel industry, coking gas – when correctly prepared<br />

and compressed – could also be fed into the long-distance gas grid. The Ruhrgas<br />

Company was set up in 1926 and immediately took advantage of the<br />

concentration of gas production in the central coking <strong>plant</strong>s to systematically<br />

raise production levels even further. Now the urban gasworks dotted all over<br />

the region gradually became superfluous and were taken out of production<br />

one by one. Coke oven gas became more and more important as a basic<br />

chemical material because of the by-products it contained like crude tar,<br />

benzene and ammonia.<br />

The Dortm<strong>und</strong> Union steelworks. Photo: 1929<br />

At first the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

delivered coking <strong>plant</strong> gas to the<br />

Dortm<strong>und</strong> Union steelworks, and<br />

later to the Phoenix steelworks. In<br />

return the coking <strong>plant</strong> received<br />

furnace gas to fire the coking<br />

ovens. Drawing: 2008<br />

10<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

WORKING HAND IN HAND – THE INTEGRATED PRODUCKTION PROCESS<br />

11

The new coking <strong>plant</strong> was<br />

planned according to the production<br />

process. Potential later<br />

extensions were also included<br />

in the overall concept. Isometric<br />

drawing: 1930<br />

One for all. In 1927 the United<br />

Steelworks began work on<br />

constructing the central <strong>Hansa</strong><br />

coking <strong>plant</strong> (photo: Battery 2).<br />

The <strong>plant</strong> replaced the coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong>s at the <strong>Hansa</strong>, Zollern,<br />

Adolf von Hansemann and<br />

Germania collieries.<br />

Photo: 1927-28<br />

At first two batteries, each<br />

containing 65 coke ovens, were<br />

constructed at <strong>Hansa</strong>. The narrow<br />

chambers, only 41 centimetres in<br />

width, were built by hand using<br />

bricks specially made to conduct<br />

heat. Photo: 1927-28<br />

Battery 2. In the backgro<strong>und</strong><br />

can be seen the presser engine<br />

which pressed the finished coke<br />

out of the oven. The photo was<br />

taken before July 1929<br />

The birth of the central <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

In 1927 the United Steelworks started work on the construction of the central<br />

<strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>. By contrast with traditional colliery coking <strong>plant</strong>s it was<br />

planned to take coal from several collieries – not only from <strong>Hansa</strong>, but also<br />

from the shafts at the Westhausen and Adolf von Hansemann collieries. The<br />

new coking <strong>plant</strong> was to be sited on an area of land 450 metres north-west<br />

of the <strong>Hansa</strong> colliery. There were two crucial reasons for this decision: it was<br />

extremely close to the Cologne to Minden railway line, and there was already<br />

a railway connection to the “Dortm<strong>und</strong>er Union” Steelworks, which also<br />

belonged to the concern and could be supplied with the coke produced<br />

almost next door. The decision to build a major coking <strong>plant</strong> in turn resulted<br />

in the expansion of the <strong>Hansa</strong> colliery to a major colliery, because it could<br />

supply above-average amounts of coking coal.<br />

It goes without saying that the ovens at the new <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> site<br />

were highly up-to-date. Larger ovens and lower baking times combined with<br />

a broad mechanisation of the ovens made it possible to raise production<br />

levels enormously from four to sixteen tons a day. The <strong>plant</strong> opened in 1928,<br />

and comprised 130 ovens arranged in batteries number 1 and 2. At the<br />

start it was planned to produce 2,200 tons of coke a day – an equivalent<br />

annual amount of 770,000 tons. The ovens were for the most part fired by<br />

blast furnace gas from the Dortm<strong>und</strong>er Union steelworks. The <strong>plant</strong> dealing<br />

with long distance gas was constructed between 1928 and 1931, thereby<br />

completing the integrated gas system between the steelworks and the Ruhrgas<br />

long distance grid. Extensions came to an end in 1934 when the large<br />

gasometer went into action.<br />

<strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>. Site map: 1930<br />

12<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

THE BIRTH OF THE CENTRAL HANSA COKING PLANT 13

Customised expansion – production planning and conception<br />

Hellmuth von Stegmann <strong>und</strong> Stein, a construction director at the United Steelworks,<br />

was given the job of drawing up the plans for enlarging the <strong>Hansa</strong><br />

coking <strong>plant</strong>. The most important feature in his conception was the arrangement<br />

of the buildings and <strong>plant</strong>s to fit in with the production process. In<br />

addition his plans allowed for further expansions at a later date.<br />

The technical <strong>plant</strong>s and buildings were arranged in an “urban development”<br />

ensemble. The basic grid was simple. There were two parallel main roads.<br />

The <strong>plant</strong>s for the coke production <strong>plant</strong>s were situated on the so-called<br />

“black” side. These included the sorting tower, the coal towel and bunkers,<br />

the mixing and crushing <strong>plant</strong>s, the coke oven batteries, the quenching towers,<br />

the coke ramps and the screening <strong>plant</strong>. The “white” side contained a row<br />

of chemical <strong>plant</strong>s for extracting and preparing the valuable by-products<br />

from the coking gas: the benzene factory, the ammonia factory, the salt store,<br />

the compressor house and the workshops. The workers’ washroom and the<br />

administrative buildings were also situated along this road.<br />

At first the compressor house was fitted out with two compressors for<br />

compressing the coking <strong>plant</strong> gas to be sent to the grid. Subsequently it was<br />

enlarged step by step. From 1942 onwards 5 gas compressors manufactured<br />

by the Demag company worked on a piece work basis. Photo: 1930<br />

A huge number of pipelines connected the “black” and “white” sides. These<br />

were, so to speak, the blood vessels and nerves of the coking <strong>plant</strong>. Alongside<br />

the two parallel main roads and the criss-cross of conveyor bridges,<br />

pipeline bridges and railway lines, there was a further important transportation<br />

system for taking the coke to the outside world. Here we should also<br />

mention the so-called “skylift”, a prominent feature of the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

skyline between 1928 and 1945. This was an overhead cableway that took<br />

the coal from the Westhausen and Adolf von Hansemann collieries directly<br />

to the sorting tower in the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>.<br />

Until 1945 coal from the Westhausen<br />

and Adolf von Hansemann colliery<br />

was delivered by overhead cable.<br />

Later this was delivered by rail.<br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> colliery delivered its<br />

coking coal via a specially constructed<br />

conveyor belt known as<br />

the “<strong>Hansa</strong> belt”. Photo: 1952<br />

14<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

CUSTOMISED EXPANSION – PRODUCTION PLANNING AND CONCEPTION<br />

15

Rearmament and expansion<br />

In the years up to 1938 the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> <strong>und</strong>erwent considerable<br />

expansion. As a result of the Nazi rearmament plans and the autarchy<br />

policies the site north of the existing coke ovens was given two new batteries,<br />

each containing eighty Koppers by-product coke ovens. At the same time<br />

the <strong>plant</strong> was given a second coal tower and a second screening area. The<br />

chemical <strong>plant</strong>s were extended, and the compressor house was enlarged to<br />

contain five additional engines. With an eye to production for the Second<br />

World War, <strong>Hansa</strong> was now the largest coking <strong>plant</strong> in the Ruhrgebiet with<br />

a capacity of 1,700,000 tons a year.<br />

Construction work on Battery 3, 1938: Extensions to the <strong>plant</strong> were<br />

completed in 1942, thereby making <strong>Hansa</strong> the largest coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

in the Ruhrgebiet. Photo: 1938.<br />

Battery 4 in action in the 1950s<br />

16<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

REARMAMENT AND EXPANSION 17

Works. At the same time the two small lean and rich gas containers that had<br />

gone into operation in 1928 were replaced by new constructions in new<br />

places on the <strong>Hansa</strong> site.<br />

In July 1968 the first coke was pressed out a new thirty-oven battery (“battery<br />

0”) south of battery 1. Now the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> comprised over 314<br />

ovens and had reached its maximum output capacity of 1,900,000 tons a<br />

year. In 1976 batteries 0 and 1 were given their own quenching houses in<br />

order to lower the levels of dust emissions when the coke was pressed out of<br />

the ovens. In 1982/83 a dry quenching <strong>plant</strong> for the coke was constructed<br />

as an alternative to the water cooling in the quenching towers. Despite the<br />

The coking <strong>plant</strong>s were strategic war targets because they were vital<br />

cornerstones for steel production in the Nazi rearmament and autarchy<br />

policies. Batteries 1 and 2 at the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> were so heavily<br />

damaged that they had to be demolished and replaced with new ones<br />

in the 1950s. Photo: 1944<br />

The post-war years were devoted to cleaning up the war damage. Batteries<br />

1 and 2 were irreparably damaged and had to be demolished, and were<br />

replaced in 1951 and 1955 respectively by new batteries each containing<br />

62 ovens. In addition, there were further construction changes. As early as<br />

1943 work began on building a generator house to produce lean gas from<br />

the <strong>plant</strong>’s own small coke and low-quality coal to supplement the lean gas<br />

supplied by the Dortm<strong>und</strong>er Union steelworks. The last of a total of 16 generators<br />

went into operation in 1955. Between 1955 and 1959 parts of the coal<br />

by-product <strong>plant</strong>s were modernised and extended with the aim of being able<br />

to produce as much coking gas as possible for long-distance supplies.<br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> was integrated into the <strong>Hansa</strong> Mining Company as<br />

early as 1953, and this in turn was taken into the Ruhrkohle Company in<br />

1969. A major organisational change came after extensions to the coking gas<br />

pipelines were completed in 1964. Now <strong>Hansa</strong> took over responsibility for<br />

supplying gas and coke to the Phoenix steelworks in the Dortm<strong>und</strong> suburb of<br />

Hörde. From 1966 onwards, after the blast furnaces at the Dortm<strong>und</strong>er Union<br />

steelworks were closed down, <strong>Hansa</strong> also took furnace gas from the Phoenix<br />

huge number of extensions,<br />

most of the essential elements<br />

in the original <strong>plant</strong><br />

built in 1928 have been<br />

retained.<br />

Repairs and extensions<br />

continually took place<br />

over the whole site<br />

during its 64 years of<br />

operation. In 1955 the<br />

“white side” was extended<br />

with the addition<br />

of new benzene stepby-step<br />

scrubber.<br />

Photo: 1955<br />

In 1983 an experimental<br />

KTK was built by the Carl<br />

Still company north of the<br />

batteries on the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong> This was later extended<br />

and remained in<br />

operation until 1992. The<br />

<strong>plant</strong> could cool ca. 80 tons<br />

of coke per hour. After 1986<br />

this was approximately 50%<br />

of production. Photo: 1983<br />

18<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

REARMAMENT AND EXPANSION<br />

19

The end – and a truly<br />

monumental new beginning<br />

<strong>plant</strong>s, and make a redevelopment study of the site. Finally, in 1998, the<br />

<strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> was inscribed into the list of protected monuments in<br />

the city of Dortm<strong>und</strong>. This did not, however, apply to the whole site but only<br />

to the most essential elements dating back to the 1920s and 1930s.<br />

The last coke was pushed out of the ovens on the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

on December 15th 1992 in a solemn and somewhat poignant final<br />

ceremony. Over the years the workers had developed an affectionate<br />

relationship to the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> despite the harsh working<br />

conditions. Photo: 1992<br />

In 1986 batteries 0 and 4 were taken out of production, and on the 15th<br />

December 1992 the last batch of coke was pressed out of the ovens and the<br />

<strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> was closed down for good. Its production – along with<br />

some of the workforce – was moved to the modern Kaiserstuhl coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

which went into operation on the 1st December 1992 on the site of the<br />

Westfalenhütte steelworks in Dortm<strong>und</strong>.<br />

On the 3rd December 1992, immediately before <strong>Hansa</strong> closed down, staff at<br />

the Westphalian Office for Monument Preservation put forward proposals to<br />

list the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> as an industrial monument. Five years later work<br />

began on a comprehensive study to evaluate the individual buildings and<br />

The value of the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> as a listed monument consists in the fact<br />

that most of the buildings and technical <strong>plant</strong>s are authentic documentary evidence<br />

of the state of coking technology in the 1920s. The clear architectural<br />

design of the buildings, their strict arrangement according to the process of<br />

production, and their ability to accommodate potential extensions with ease,<br />

clearly reflect – despite later modernisation phases – the “classical” demands<br />

made on the industrial buildings of the modern age. These demands are still<br />

basically valid today. Furthermore the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> is the last extant<br />

major coking <strong>plant</strong> from the 1920s in the Ruhrgebiet to systematically integrate<br />

the production output from a colliery, a coking <strong>plant</strong>, a steelworks, and<br />

the long-distance gas grid. The compressor house is of particular value for<br />

its five pairs of steam-driven gas compressors dating back to 1927/28 and<br />

1941/42 respectively. Alongside the historical technical and architectural<br />

aspects, the urban planning significance of the industrial site in connection<br />

with the growth of the suburb of Huckarde is also a relevant factor in its<br />

value as a listed monument.<br />

Closed. When the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong> was taken out of operation<br />

in 1992 its future as an industrial<br />

monument was not yet secure.<br />

Photo: 1993<br />

20<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

THE END – AND A TRULY MONUMENTAL NEW BEGINNING 21

Good times<br />

The decision to preserve the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> for future generations was<br />

taken at a boom time for industrial monument conservation in the state of<br />

North-Rhine Westphalia. Comprehensive programmes and tools for preserving<br />

and redeveloping industrial monuments were created on the basis of the careful<br />

use of resources and their sustainability. At the same time, since the mid-<br />

1970s, increased value was put on documenting, researching and mediating<br />

the industrial history in North-Rhine Westphalia. This led, amongst others,<br />

to the establishment of the Westphalian Industrial Museum in 1979, and the<br />

Rhineland Industrial Museum in 1984.<br />

Another milestone was set between 1989 and 1999 with the Emscher Park<br />

International Building Exhibition, a programme intended to accompany and<br />

master the problems of structural transformation of a region based on heavy<br />

industry to one based on service and information. The International Building<br />

Exhibition made a huge contribution to the conservation of industrial buildings<br />

and, at the same time, shone a public spotlight on the theme of industrial<br />

history and culture. Its successes speak for themselves. The former ironworks<br />

in the Duisburg suburb of Meiderich is now an industrial landscape park<br />

which attracts huge amounts of visitors. The Gasometer in Oberhausen and<br />

the mixing <strong>plant</strong> in the Zollverein mining complex in Essen are uniquely<br />

compelling exhibition venues for arts and culture. The initial ideas to set up<br />

an Industrial Heritage Trail, as a tourist attraction connecting all the most<br />

important industrial venues in the Ruhrgebiet in a 400 kilometre circuit, also<br />

date back to the 1990s.<br />

A further unique institution nationwide is the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the Preservation<br />

of Industrial Monuments and Historical Culture which was set up in 1995. It<br />

is committed to preserving first-class industrial monuments with the aim of<br />

protecting them from abolition, securing their existence, researching the<br />

The “Vitale Areale” show heralded in the era of the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> as an<br />

industrial monument. The photo shows a scene from “Three Sisters” by Anton<br />

Chekhov. Photo: 1999<br />

history, making them accessible to the general public and redeveloping them<br />

for new uses corresponding to their listed status.<br />

The Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the Preservation of Industrial Monuments and Historical<br />

Culture is responsible for many different mining sites in North Rhine Westphalia.<br />

These include the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>, whose historical administrative<br />

buildings have contained the organisation’s business headquarters since<br />

1997. Two years later, on the 1st April 1999, the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> was<br />

opened as an anchor point along the Industrial Heritage Trail. For the first time<br />

tourists were able to explore the monument along a theatrically staged adventure<br />

trail during a major celebratory event entitled “Vitale Areale – Forum Interart”.<br />

There was a huge positive reaction from the general public. No less<br />

than 10.000 visitors poured into the site to explore the once “forbidden city”.<br />

22<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

GOOD TIMES 23

Clever planning<br />

The master plan foresaw the visitor trail, “Nature and Technology”, along with<br />

a link from the coking <strong>plant</strong> to the “Deusenberg” spoil tip and an opening to<br />

the suburb of Huckarde. Master plan: 2001<br />

In 2001 the city of Dortm<strong>und</strong> commissioned the landscape architects, Davids,<br />

Terfrüchte and Partners, to produce a master plan for the development of the<br />

<strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>. With reference to a study made by the Westphalian Office<br />

for Monument Conservation in 1997 the master plan came out in favour of a<br />

tourist profile for the site, including the construction of visitors trails. The f<strong>und</strong>amental<br />

aim was to develop the coking <strong>plant</strong> as a sort of “accessible gigantic<br />

sculpture”. The design of several different areas foresaw an orientation towards<br />

the central theme of “nature and technology”. Furthermore, urban components<br />

were accentuated and proposals were made to open up the industrial <strong>plant</strong><br />

to the neighbouring suburb of Huckarde to the south and to the west, by integrating<br />

new buildings. The proposal to link the monument with a regenerated<br />

landfill site to the east by means of a pedestrian bridge also proved crucial.<br />

Today the Deusenberg site is a popular venue for football and other sporting<br />

activities. Plans are currently being made to build a ring road aro<strong>und</strong> the site.<br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> was at<br />

first retained in its complete form.<br />

Finally, however, only the listed<br />

<strong>plant</strong>s were preserved. This meant<br />

that the gasometer, the second<br />

coal tower and the coke dry<br />

cooling <strong>plant</strong> had to be dispensed<br />

with. Photo: 2002<br />

Today the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

comprises the basic buildings as<br />

they were in the 1920s and 30s.<br />

Photo 2008<br />

The master plan was completed in 2001 on the assumption of preserving the<br />

buildings on the coking <strong>plant</strong> as they were at the time of its closure in 1992.<br />

In the years between, however, the number of buildings was considerably<br />

reduced. The monument authorities basically concentrated their attention on<br />

preserving the buildings and <strong>plant</strong>s from the 1920s. This meant that a number<br />

of different buildings and <strong>plant</strong>s from later periods were demolished according<br />

to the legal rights of their former owner, the RAG holding company. These<br />

included the gasometer, coal tower II, screening <strong>plant</strong> II and the dry<br />

quenching <strong>plant</strong>.<br />

The reduction in the buildings on the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> and the corresponding<br />

reduction in the overall gro<strong>und</strong> area, made it necessary to adapt the master<br />

plan to the new conditions. That said, the basic criteria for developing the<br />

<strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> as a gigantic accessible sculpture remained untouched.<br />

24<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

CLEVER PLANNING 25

New paths<br />

Several so-called monument paths for visitors were constructed at the <strong>Hansa</strong><br />

coking <strong>plant</strong> between 1998 and 2003. The Heinrich Böll architectural<br />

office in Essen was commissioned to implement the building project. In three<br />

building phases all the most important areas of production were linked by a<br />

system of paths consisting of accessible conveyor bridges, pipeline bridges<br />

and ramps. In order to open up the maximum number of different perspectives<br />

the monument was also made accessible on different levels. Visitors can now<br />

move aro<strong>und</strong> the gro<strong>und</strong> area on the ring road surro<strong>und</strong>ing the monument,<br />

and learn more about the structure of industrial production on the “black side”<br />

where the coke was produced, and the “white side” when the gas was<br />

processed into by-products. A further path provides access to the heart of the<br />

coking <strong>plant</strong>, the coke ovens, and leads over to the white side containing the<br />

“chemical factory”. A third trail leads visitors along the path of coal to the<br />

coke oven batteries via conveyor belt bridges and past imposing accessible<br />

coal bunkers.<br />

“Transparent” conveyor bridges and panoramic windows enable visitors to<br />

get fascinating views of the industrial <strong>plant</strong> and offer them the chance to get<br />

their bearings in the industrial <strong>plant</strong> with respect to the suburb of Huckarde<br />

and the city of Dortm<strong>und</strong>.<br />

No matter which paths visitors choose to take, the compressor house with its<br />

valuable collection of historical technical engines is always a high point along<br />

the circular tour. Apart from producing coke, the gas released by the coking<br />

process was the second most important area of production in the <strong>Hansa</strong><br />

coking <strong>plant</strong>. The compressors made by the DEMAG company were used to<br />

feed the coking gas into the Ruhrgas grid. They are important monuments to<br />

the early long-distance gas production that took off in the 1920s, and mainly<br />

supplied industry and domestic households with coking gas.<br />

Visitors can acquaint themselves<br />

with the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong> on the „Nature and Technology“<br />

adventure trail. The<br />

path leads via “transparent”<br />

conveyor belt bridges, past<br />

bucket elevators, through coal<br />

bunkers to the coke ovens, and<br />

via pipe bridges to the „white<br />

side“, the „chemical factory“<br />

on the coking <strong>plant</strong>.<br />

Photos: 2003-2009<br />

26<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

NEW PATHS<br />

27

Industrial nature is welcomed at the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>. Within<br />

the space of a few years a birch grove has sprung up on the<br />

“roofs” of the coke ovens. Photo: 2005<br />

Roof gardens on the coking ovens<br />

On their tour of the coking <strong>plant</strong> visitors can not only explore a number of<br />

industrial legacies but also a coking <strong>plant</strong> in the midst of natural green surro<strong>und</strong>ings.<br />

Indeed the general development of the area is based on a highly<br />

unusual concept with respect to monument conservation: to unite historical architecture<br />

and technology with the untamed growth of “industrial nature” into<br />

a new overall environment. The concept of industrial nature generally refers<br />

to the flora and fauna growing on disused industrial sites. New man-made<br />

landscapes have been built up in places like collieries, coking <strong>plant</strong>s and<br />

steelworks due to the amassment of slag, dead rock, dust, ashes and building<br />

rubble. The resulting gro<strong>und</strong> can only absorb small amounts of moisture and<br />

contains very few nutritive substances. In addition, a large proportion of dark<br />

materials like coal dust mean that the gro<strong>und</strong> warms up much more quickly<br />

<strong>und</strong>er sunlight than other more typical gro<strong>und</strong>s in the region. Despite the<br />

man-made terrain there are a large number of different species of <strong>plant</strong>s and<br />

animals which flourish on the difficult conditions inherent in disused industrial<br />

spaces. The resulting areas of industrial woodland are now <strong>und</strong>er the supervision<br />

of a forestry officer employed by the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the Preservation<br />

of Industrial Monuments and Historical Culture to care for the “Ruhrgebiet<br />

industrial woodland project”. This is not a forestry business in the traditional<br />

sense of the word. It rather prefers to abandon the site to natural forces,<br />

thereby allowing <strong>plant</strong>s and animals to develop, for the most part free of<br />

human intervention or influences.<br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> is not only an anchor point along the tourist Industrial<br />

Heritage Trail in the Ruhrgebiet, it is also part of the “industrial nature” theme<br />

trail and, in addition, since 2006, a part of the European Garden Heritage<br />

Network. As a result, further redevelopment plans are being drawn up during<br />

the coming years on the existing basis of “nature and technology”. Several<br />

concrete plans now exist: a “forestry station” is to be constructed in the former<br />

warehouse building. It will contain an exhibition space to illustrate themes like<br />

the environment, sustainability, nature, society and power, especially with a view<br />

to catering for school groups. Furthermore it is planned to turn the former laboratory<br />

building and its historic equipment in the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> into a “paint<br />

laboratory” for children, equally dedicated to producing paints from <strong>plant</strong>s as<br />

well as from the by-products directly associated with the old coking <strong>plant</strong>.<br />

28<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

ROOF GARDENS ON THE COKE OVENS 29

Rain collectors and cloud makers<br />

Even during the time it was in operation the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> was a sort<br />

of laboratory for technical improvements. These included the construction of<br />

a quenching house and a dry quenching <strong>plant</strong>. The current owner of the<br />

coking <strong>plant</strong>, the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the Preservation of Industrial Monuments<br />

and Historical Culture, also makes no bones about its open attitude towards<br />

technical innovations. In 1999, in recognition of a new generation of regenerative<br />

power – it built a photovoltaic <strong>plant</strong> on a building in the coking <strong>plant</strong> on<br />

the Zollverein World Heritage site in Essen. The <strong>plant</strong> is still run by the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation<br />

and now has an output of ca. 218,000 watts. The Fo<strong>und</strong>ation is planning<br />

to join forces with the “Emschergenossenschaft” for a further innovation –<br />

a hydraulic power project at the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> as part of an agreement<br />

to promote rainwater in the future. This agreement represents a common<br />

commitment made by all the towns and cities in the Emscher area, the Ministry<br />

for the Environment and the “Emschergenossenschaft“ to lower the demands<br />

made on the sewage system by 15% in the next 15 years by the use of rain<br />

and pure water. This challenging target means that pure water will then no<br />

longer be unnecessarily conducted to the clarification <strong>plant</strong>s, but put straight<br />

back into the natural water circulation. Rain falling on the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

will be collected in a special basin and in specially paved surface conduits<br />

leading to reservoirs by the old cooling tower. The rainwater will then be<br />

warmed up by the photovoltaic solar panels installed there, and evaporated<br />

aro<strong>und</strong> 30 to 40 times a year in the form of a visible cloud of steam rising<br />

into the sky.<br />

Perhaps clouds of smoke will soon be rising once again into the sky above<br />

<strong>Hansa</strong>, when rainwater collected in the basins of the cooling tower is heated<br />

up and evaporated. Project simulation: 2010<br />

30<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

RAIN COLLECTORS AND CLOUD MAKERS 31

tecture and technology, via industrial work, working clothes, language, coal<br />

and coke, all the way to monument preservation and new artistic uses. The<br />

projects inspire the young students to do their own research in a familiar<br />

environment, to communicate with parents, grandparents and neighbours,<br />

question them as contemporary witnesses about mining and factory work, and<br />

get acquainted with people’s recollections as an important source of historical<br />

legacies. Furthermore the students are motivated to bring their own exhibits<br />

into the classroom: things like a miner’s helmet, an old working glove, a butter<br />

dish, photos or newspapers. In this way they learn to put a value on everyday<br />

industrial objects. Lastly, art lessons give them the opportunity to work on<br />

these “memoirs” and enrich them with their own personal impressions and<br />

imagination. They can then recount new “stories” on the basis of the old ones.<br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> has proved its worth as an extra curricular<br />

place of learning. Every year on the open day, school students<br />

from the Gustav Heinemann comprehensive school in Dortm<strong>und</strong><br />

exhibit the results of their projects. Photo: 2005<br />

Since 2005 the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the Preservation of Industrial Monuments has<br />

been co-operating with the Gustav-Heinemann comprehensive school in the<br />

suburb of Huckarde, on projects that are presented at open days in the form<br />

of an exhibition in the compressor house at the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>. In 2008<br />

the school students won a national competition with a project entitled “The<br />

Rusty Gardens in the <strong>Hansa</strong> Coking Plant”<br />

An extra curricular place of learning<br />

For some years now the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> has been used as an extracurricular<br />

place of learning. During project weeks school students study the <strong>Hansa</strong><br />

coking <strong>plant</strong> in order to get to know it in more detail. They collect impressions<br />

of the local suburb by observation, photography and drawing. The "images"<br />

of coal towers, machines, pipelines, <strong>plant</strong>s and animals later serve to jog their<br />

memories as a basis for further work, for example, in art lessons. The <strong>Hansa</strong><br />

coking <strong>plant</strong> offers a huge spectrum of themes ranging from industrial archi-<br />

32<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

AN EXTRA CURRICULAR PLACE OF LEARNING 33

The art lab<br />

The <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> is not only a magnet for people interested in technology<br />

and nature. Since it first opened in 1999 artists have been continually<br />

seeking a dialogue with the monument in order to gain inspiration from its<br />

industrial past and structural transformation.<br />

The owner of the coking <strong>plant</strong>, the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the Preservation of Industrial<br />

Monuments and Historical Culture , which is simultaneously responsible for<br />

preserving, researching and opening up the site for new uses, regards artistic<br />

activities as an enrichment to its programme of events and to “staging” the<br />

site. Artistic contributions can also provide critical comments and questions<br />

regarding the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation’s concepts, as well as on factors like building and<br />

landscape planning, and redevelopment. At times they might even be able<br />

to reformulate such concepts. In this way artistic reflections on the past and<br />

present history of the monument are part of a process of development which<br />

demands an open-ended dynamic approach.<br />

Art projects are a basic part of the development process at the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong>. In the exhibition “Forbidden City” Stefan Sous presented his project<br />

“Smoke – new sandalwood aroma” in the compressor house to demonstrate<br />

the process of transformation from an industrial <strong>plant</strong> to a monument adapted<br />

for new uses. Photo: 2002<br />

In the exhibition entitled “Speed” Caspar<br />

Pauli drew his inspiration from material flow<br />

and changes, as well as from the building<br />

structures at the coking <strong>plant</strong>. Photo: 2009<br />

34<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

THE ART LAB<br />

35

A well-preserved monument<br />

Preserving the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> for future generations is an awesomely<br />

responsible duty. It is not only about preserving the buildings but also the<br />

complex technical equipment and <strong>plant</strong>s. The original architect of the coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong>, Hellmuth von Stegmann <strong>und</strong> Stein (1891-1929), was only too aware<br />

of the importance of engineering aspects when taking account of the overall<br />

impression made by an industrial <strong>plant</strong>. He felt it was necessary to “be clear<br />

about the fact that purely engineering constructions like storage tanks, chimney<br />

stacks, chamber coolers, large-scale pipelines etc, are very often at least<br />

as important in creating an overall impression of an industrial <strong>plant</strong> as the<br />

aesthetics […] of the buildings. On many occasions a well thought-through<br />

concept on how to arrange the buildings containing the machines and<br />

engineering equipment is much more important than a purely formal arrangement<br />

of high buildings, however successful this might be.<br />

A huge responsibility. The preservation of the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> industrial<br />

monument. Not only the buildings but also the technical equipment have to<br />

be conserved. Photo: 2008<br />

The Fo<strong>und</strong>ation agrees with this opinion entirely and this is why it has decided<br />

to devote its energies to preserving as many of the technical and engineering<br />

buildings as possible in order to document the history of the technology, production<br />

and the economy, not forgetting the ideal overall impression of a typical<br />

industrial <strong>plant</strong> in the 1920s.<br />

The many containers and pipelines<br />

that make up the “arterial system”<br />

of the coking <strong>plant</strong> should also<br />

be preserved where possible.<br />

Photo: 2003<br />

36<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

A WELL-PRESERVED MONUMENT 37

The gas compressors were completely cleaned up in 2006. They are the highlight of<br />

every tour. During a guided tour visitors can watch one of the gas engines in action.<br />

Photo: 2005<br />

At first the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation assumed that parts of the <strong>plant</strong> like the coke oven<br />

batteries, storage tanks and pipelines should be successively allowed to fall<br />

into a controlled state of dilapidation, and many ideas were thrown aro<strong>und</strong><br />

concerning the picturesque images of overgrown oven ruins. But these ideas<br />

were not pursued further because those in charge realised that allowing the<br />

side to fall into a controlled state of disrepair would be tantamount to a continual<br />

process of dismantling. The corroding and collapsing parts of the site<br />

could not simply be left to themselves and natural influences, because this<br />

might very well result in gro<strong>und</strong> pollution. If so, it would be impossible to<br />

allow the ruins to remain on the site and they would have to be removed.<br />

The monument would therefore gradually disappear.<br />

huge monument can only take place step-by-step – not least for financial<br />

reasons – and therefore needs years of hard work, the Fo<strong>und</strong>ation for the<br />

Preservation of Industrial Monuments and Historical Culture has opted to deal<br />

with specific sections of the site, like the construction of visitor trails. The primary<br />

consideration was to ensure that the whole site was accessible to visitors.<br />

As result the aim was to develop a system of paths which was not only<br />

safe, but also linked all the most important areas of production in the coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong>. Thus cleaning up the areas beyond the trails, like the facades of the<br />

coal towers, could be postponed or even entirely disregarded. The same<br />

applied to the interior of the building which, like the coal bunkers, were also<br />

only “parsimoniously” cleaned up. Many visitors fo<strong>und</strong> this approach extremely<br />

attractive because the view from the trails allowed them to get a view<br />

of areas still blackened with coal dust which seemed to have been left almost<br />

untouched. This allowed them to get a much closer and intimate idea of the<br />

industrial history of the site. The resulting atmosphere has played a very important<br />

part in producing an emotional response to the coking <strong>plant</strong> and this<br />

has resulted in an increased interest in the work that once took place here.<br />

The approach to the compressor house at the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> was utterly<br />

different. The building was completely cleaned up, the valuable collection of<br />

engines restored, and an area created for events. The fresh white coat of<br />

paint given to the interior walls of the building <strong>und</strong>erlines its museum atmosphere<br />

and the new uses to which it can be put.<br />

The overall concept behind conserving the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> is clearly not<br />

static, but dynamic and open. Here concepts for landscape designs, partial<br />

redevelopment, complete redevelopment, basic safety measures and overall<br />

care stand alongside one another in a flexible framework. Last not least,<br />

f<strong>und</strong>ing problems demand that we adopt such an approach. The individual<br />

building blocks and strategies for dealing with the monument all mesh in<br />

together and – even in their apparent contradictions – this is what makes the<br />

challenges involved in preserving the coking <strong>plant</strong> so exciting.<br />

Many different strategies are being pursued to preserve the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong>, all of which are part of an overall plan. Because cleaning up such a<br />

38<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

A WELL-PRESERVED MONUMENT 39

From coal to coke –<br />

a trip through the production<br />

process in a coking <strong>plant</strong><br />

What is a coking <strong>plant</strong> – a brief introduction<br />

In a coking <strong>plant</strong> coal is loaded into hermetically sealed chambers and<br />

heated to high temperatures in coking ovens arranged in batteries of several<br />

dozen narrow chambers. The coal is then baked in the ovens for aro<strong>und</strong><br />

twenty hours at over 1000 degrees Celsius and the so-called “volatile materials”<br />

are drawn off. This process results in coke .Because of its higher carbon<br />

content, its purity and its calorific solidity coke is a more valuable fuel than<br />

coal. This is why it is primarily used for fuelling blast furnaces producing pig<br />

iron in steel and ironworks<br />

One by-product of the baking process is the crude gas which is then siphoned<br />

out of the ovens. The crude gas not only contains pollutants like hydrogen<br />

sulphide but also ammonia, crude benzene and tar. These so-called by-products<br />

are then separated from the gas in further production steps. Some of<br />

them are cleaned up and sold on as valuable products on the market. When<br />

coke production in Germany was at its height the by-products were important<br />

basic materials for the chemical industry. The cleaned up coking gas – it was<br />

known as rich gas – was sold off as fuel for steel mills and other industrial<br />

factories, or as domestic gas in the Ruhrgebiet. Gas production was a lucrative<br />

business for the coking industry until the mid-1960s when gas suppliers<br />

gradually rejected it in favour of natural gas.<br />

The production process in a coking <strong>plant</strong> is primarily divided into two main<br />

areas. The buildings used for handling the coal and producing the coke<br />

are known as the “black side”, and the by-products from the coking gas are<br />

separated and cleaned up in the buildings on the “white side”. The buildings<br />

in the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> make it possible for visitors not only to follow the<br />

process of producing coke, but also to get a greater <strong>und</strong>erstanding of the<br />

subsequent processing of the coking gas into its by-products.<br />

The production process in a coking <strong>plant</strong> never stops. For this reason all the<br />

activities including the workers’ shifts have to fulfil a single aim: to ensure<br />

that there are no stoppages whatsoever. Once a battery of coke ovens has<br />

been heated up – a process that often takes several months - it must in no<br />

circumstances be allowed to cool down again, otherwise this will result in<br />

irreparable damage to the walls of the battery. Minor interruptions in the<br />

pressing process, or defective parts must be remedied or replaced whilst the<br />

battery is still in operation. This demands a high level of efficiency not only<br />

from the mechanical parts involved, but also from the workers involved in<br />

maintaining them.<br />

We shall now describes the path of coal and the path of the crude gas as<br />

they pass through the various areas of production in the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong>;<br />

beginning with coal deliveries, continuing with the baking process and ending<br />

with the finished coke and its by-products. The <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> provides<br />

an ideal example of the complex processes involved in such an industrial site.<br />

40<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

FROM COAL TO COKE 41

The coke oven battery<br />

The various sorts of coal were<br />

crushed and mixed in the<br />

sorting tower. The so-called<br />

coking coal was then transported<br />

via a bucket elevator<br />

to the coal tower, from where<br />

it was driven to the ovens in a<br />

charging wagon. This picture<br />

shows the coal tower (centre)<br />

with a charging wagon beneath,<br />

and the sorting tower<br />

(right). In the foregro<strong>und</strong>,<br />

the oven roof with the filling<br />

holes. Photo: end of the<br />

1920s<br />

The coke oven batteries<br />

and the coal tower are the<br />

technical and architectural<br />

heart of the “black side”.<br />

Photo: end of the 1920s<br />

The path of coal<br />

Delivery<br />

When the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> was running at<br />

maximum capacity workers were able to produce<br />

aro<strong>und</strong> 5,200 tons of coke per day from 7,000<br />

tons of coal. This meant working ro<strong>und</strong> the clock<br />

and constant deliveries of fresh coal. The coal was<br />

delivered from the nearby <strong>Hansa</strong> colliery and from<br />

two other Dortm<strong>und</strong> collieries, Westhausen and<br />

Adolf von Hansemann. Coal from the <strong>Hansa</strong> colliery<br />

was delivered via a conveyor belt – known<br />

as the <strong>Hansa</strong> belt – which led directly into the<br />

<strong>Hansa</strong> corner tower on the site of the coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong>. The other collieries delivered their coal to<br />

the coking <strong>plant</strong> by cable car until 1945, and subsequently<br />

by rail.<br />

In order to produce high-value coke it is necessary<br />

to blend different sorts of coal into a specific mixture.<br />

For this reason the coal has to be specially<br />

prepared before it is baked into coke. Coal exists<br />

in several different qualities that are graded,<br />

amongst others according to the amount of volatile<br />

by-products they contain. The coal is not sorted<br />

before it leaves the collieries but is simply delivered<br />

on conveyor belts to the bunkers next to the sorting<br />

tower in the coking <strong>plant</strong>. The first step in the process<br />

of producing coke is therefore to mix the different<br />

grades of coal correctly. Once it has been<br />

mixed it is taken from the sorting tower to the coal<br />

towers above the coke oven batteries. If necessary,<br />

the mixture of coal can be crushed down into even<br />

finer nuts.<br />

The coking process took place in the coke ovens.<br />

The individual oven chambers were all contained<br />

in a single battery because this was the most efficient<br />

way of heating and controlling them. During<br />

boom periods of production there were five batteries<br />

at the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> comprising a total<br />

of 314 coke ovens. Every single oven chamber is<br />

a narrow walled space consisting of highly efficient<br />

heat-conducting silicone bricks. At <strong>Hansa</strong> the ovens<br />

were 13 metres long, 4 metres high and only 41<br />

centimetres wide. The sides of the ovens were<br />

hermetically sealed by cast-iron doors.<br />

A mixture of combustible gas and air is burnt in<br />

the walled-up hollow spaces – so-called combustion<br />

walls – between every two ovens. In the regenerative<br />

ovens that began to predominate in 1911,<br />

the combustion air was first warmed in heated<br />

stone constructions beneath the ovens, known<br />

as regenerators. This meant that much less selfproduced<br />

gas was needed to heat the ovens to<br />

the desired temperature of 1,250 degrees Celsius.<br />

In addition regenerative ovens enabled the ovens<br />

to be fired with furnace gas instead of the more<br />

usual rich gas. At <strong>Hansa</strong>, furnace gas was taken<br />

from the nearby steelworks and supplemented with<br />

a certain proportion of self produced rich gas.<br />

Charging wagons were responsible for loading the<br />

oven chambers. They ran on railway lines along the<br />

roof of the batteries beneath the coal tower where<br />

they were loaded with aro<strong>und</strong> 15 tons of coal.<br />

During this time a worker standing on the roof of<br />

the ovens that were due to be filled, would open the<br />

five filling holes in the oven roof with the help of a<br />

hook. The charging wagons would then be driven<br />

In order to guarantee a constant<br />

temperature level in the ovens<br />

the hollow spaces in the heating<br />

walls had to have a particular<br />

shape. An oven chamber<br />

(centre), flanked by two heating<br />

flues. Photo: the 1920s<br />

The filling wagon was driven<br />

over the battery by electricity,<br />

and dropped its load of coal<br />

into the ovens through a conical<br />

opening. During this process air<br />

and some of the first coking gas<br />

with its dangerous substances<br />

escaped. Starting in the 1970s<br />

a special wagon was docked at<br />

Battery 4 to suck off any crude<br />

gas that might escape. Photo:<br />

the 1980s<br />

42<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

THE PATH OF COAL 43

Any damage to the walls of<br />

the coking ovens was repaired<br />

during running operations.<br />

To do this the workers were<br />

fitted out with protective clothing.<br />

Nonetheless they had<br />

to endure incredibly high<br />

temperatures. The workers<br />

even had to intervene when<br />

the coke blocked up as it<br />

was being pressed out of<br />

the ovens. For this they got a<br />

so-called “de-blocking” bonus.<br />

Photo: end of the 1960s<br />

above the holes from where they would empty the<br />

coal through conical inlets in the ovens. If any coal<br />

happened to land on the roof of the ovens one of<br />

the workers would sweep it back into the ovens by<br />

hand. The filling holes were then closed and sealed<br />

with a claylike mass poured aro<strong>und</strong> the lid. The<br />

filling process causes so-called “filling cones” in the<br />

ovens, similar to the small cones of sand which<br />

build up when you let it run through your fingers.<br />

For technical reasons, however, the surface of the<br />

coal must remain even because an empty space<br />

above the coal is needed to collect the gas resulting<br />

from the coking process. For this reason the pressing<br />

machine would then open up a small flap on<br />

top of the oven and insert a so-called leveller bar<br />

into the oven to level out the cones of coal caused<br />

by the filling process. The flap would then be closed<br />

and coking could begin.<br />

The mixture of coal was heated in hermetically<br />

sealed oven chambers at temperatures of over<br />

1000 degrees Celsius for aro<strong>und</strong> 20 hours, during<br />

which time the volatile materials – aro<strong>und</strong> one<br />

quarter of the charge – were removed. Thus one<br />

ton of coal resulted in aro<strong>und</strong> 750 kilograms of<br />

coke. The volatile materials in the crude gas were<br />

caught in rising pipes and collecting mains, and<br />

conducted to the white side of the production <strong>plant</strong><br />

to produce the by-products of crude tar, crude<br />

benzene, sulphuric acid and ammonium sulphide.<br />

More in the chapter entitled “The Path of Gas”.<br />

The coke pusher engines and the<br />

quenching wagons<br />

When the coke cake, as the molten coke mass<br />

was called after it had been baked, was ready, the<br />

pusher ram or coke pushing machine came into<br />

operation on the machine side (hence the name).<br />

First it unlocked the oven door, pulled the door out<br />

of the opening and moved it to one side. Then it<br />

inserted a long rod, at the front of which was attached<br />

a pusher head, into the oven and pushed the<br />

coke out through the other side. After that it closed<br />

the door once more. Fresh batches of coal could<br />

then be fed into the ovens once more from above.<br />

It goes without saying that the ovens were also<br />

opened on the opposite side – the coke side. This<br />

was done by a coke cake guide car. Just like the<br />

pusher ram it unlocked the door and lifted it out to<br />

one side. After that it placed a steel guiding device<br />

in front of the oven to ensure that the entire coke<br />

cake fell into the quenching wagon. Both the pusher<br />

ram and the coke cake guide car were driven by<br />

a single engineer. Later the two engineers could<br />

coordinate their work by radio.<br />

The quenching tower<br />

The coking process in the oven chambers can only<br />

take place if they are hermetically sealed. If there<br />

is any oxygen in the oven chambers the coal will<br />

simply burn and not be baked to coke. As soon as<br />

the molten coke leaves the oven, of course, it comes<br />

back into contact with air and catches fire immediately.<br />

To prevent it burning to ashes it has to be<br />

cooled down as quickly as possible: or to use the<br />

workers’ jargon, “quenched”. This explains why a<br />

quenching wagon is standing ready to transport the<br />

molten coke to the quenching tower as soon as it is<br />

The finished coke known as<br />

“coke cakes” was pushed<br />

out of the ovens by pusher<br />

engines. This took place<br />

every 7 minutes according to<br />

a fixed scheme. Photo: 1950s<br />

When the molten coke came<br />

out of the oven it caught<br />

fire immediately. This is why<br />

it had to be transported to<br />

the quenching tower.<br />

Photo: 1968<br />

“Cloud makers”. Every time<br />

coke was quenched at the<br />

coking <strong>plant</strong> a huge cloud of<br />

smoke rose up into the sky.<br />

Photo: 1992<br />

44<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

THE PATH OF COAL 45

After it had been quenched<br />

the coke was tipped out onto<br />

the ramp to cool down. Any<br />

remaining fire was quenched<br />

by hand by the ramp man<br />

with the aid of a simple hose.<br />

Photo: the 1920s<br />

After the coke had been completely<br />

quenched it was taken<br />

to the screening <strong>plant</strong><br />

to be sorted into different<br />

sizes before being loaded<br />

into railway wagons and<br />

transported to the steelworks.<br />

Photo: the 1920s<br />

pushed out of the oven. The quenching tower is a<br />

construction made of concrete and timber, beneath<br />

which the burning coal is quenched with sprays of<br />

water. This process produces a characteristic cloud<br />

of steam that billows out above the coking <strong>plant</strong>. At<br />

the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> this occurred every seven minutes<br />

when production was at its height.<br />

A dry quenching <strong>plant</strong> is another way of cooling<br />

down the coke after it has been pushed out of the<br />

oven. These are quenching <strong>plant</strong>s in which a cooling<br />

gas, like, for example, the inert gas nitrogen, is passed<br />

over the molten coke. The advantage of the dry<br />

quenching method is that the heat in the molten coke<br />

does not evaporate into steam but can be recaptured<br />

in the gas and used elsewhere. That said, such a<br />

<strong>plant</strong> involves a huge investment, and the running<br />

costs are also considerable. This is why it only pays<br />

to use dry quenching equipment <strong>und</strong>er very particular<br />

preconditions.<br />

After the coke had been quenched the quenching<br />

wagon would return to the oven battery to tip out the<br />

quenched coke onto a ramp. This is where the ramp<br />

man worked, who had to check to ensure that all the<br />

molten mass had been quenched. If this was not the<br />

case, he had to put out any remaining burning coke<br />

with a hosepipe. After the coke was completely<br />

quenched it would be left for roughly half an hour to<br />

cool down on the ramp before being transported on<br />

a conveyor belt to the screening <strong>plant</strong>s. Here the<br />

coke would be broken up and sorted into different<br />

sizes and then loaded onto railway wagons.<br />

The path of gas<br />

Drawing off the crude gas<br />

We have already mentioned that coking coal produces<br />

a by-product known as crude gas. Each full<br />

oven charge produced aro<strong>und</strong> 5,200 cubic metres<br />

of gas: at the <strong>Hansa</strong> coking <strong>plant</strong> this amounted to<br />

aro<strong>und</strong> 95,000 to 100,000 cubic metres of gas<br />

per hour. The gas collected in the space above the<br />

red-hot coal in the ovens. Each oven and chamber<br />

was equipped with a vertical upward pipe to draw<br />

off the crude gas during the coking process. Large<br />

gas exhausters transported the crude gas via tapping<br />

conduits and gas collectors to the gas preparation<br />

buildings on the white side of the coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong>. Here the by-products were separated from<br />

one another and the gas was prepared to be fed<br />

into the long-distance gas grid. On average one<br />

ton of coke would produce 40 kg of crude tar, 8<br />

to 10 kg of crude benzene and 3 kg of ammonia.<br />

Producing the by-products tar and phenol<br />

As soon as the hot crude gas had left the oven via<br />

the conduit pipes it was cooled down to aro<strong>und</strong><br />

90°C in the elbows of the pipes by spraying it with<br />

water. This process produced the first by-product:<br />

crude tar, which was dissolved in the condensed<br />

coal water and conducted with the crude gas<br />

through the conduits. The condensed steam was<br />

captured in a funnel in the so-called tar extractor.<br />

The heavy solid matter was deposited here, and<br />

the dissolved tar was separated from the water by<br />

a “Koppersche” pressure separator. At <strong>Hansa</strong>,<br />

minuscule particles and aerosols remaining in the<br />

crude gas were removed in the electric gas purification<br />

<strong>plant</strong>, which consisted of four electro-filters.<br />

The crude gas was taken<br />

from the coke ovens via a<br />

pipeline to the “white side”.<br />

This process was regulated<br />

and controlled by a worker.<br />

This picture was taken at<br />

one of the Hibernia coking<br />

<strong>plant</strong>s. Photo: the 1950s<br />

46<br />

HANSA COKING PLANT – THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL MONUMENT<br />

THE PATH OF GAS 47

The huge number of by-products<br />

from crude gas. For<br />

many years coking <strong>plant</strong>s<br />

delivered important basic<br />

materials in the form of their<br />

by-products, most especially<br />

to the chemical industry.<br />

All the tar fractions were then purified once again<br />

and collected in tar containers. The tar was then<br />