Read the Full Article (PDF, 1.2 MB) - Datacolor

Read the Full Article (PDF, 1.2 MB) - Datacolor

Read the Full Article (PDF, 1.2 MB) - Datacolor

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

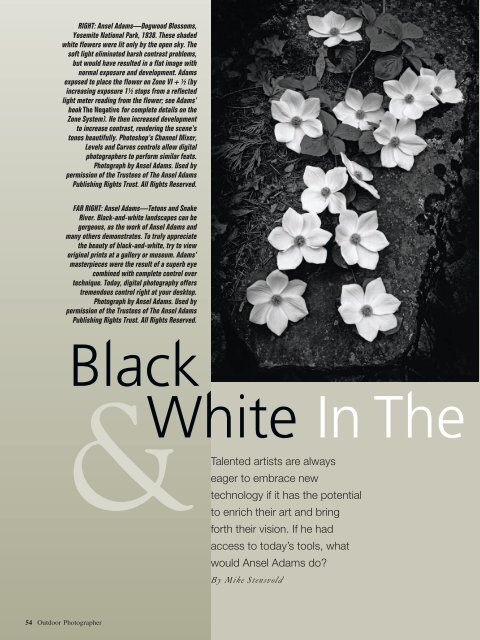

RIGHT: Ansel Adams—Dogwood Blossoms,<br />

Yosemite National Park, 1938. These shaded<br />

white flowers were lit only by <strong>the</strong> open sky. The<br />

soft light eliminated harsh contrast problems,<br />

but would have resulted in a flat image with<br />

normal exposure and development. Adams<br />

exposed to place <strong>the</strong> flower on Zone VI + ½ (by<br />

increasing exposure 1½ stops from a reflected<br />

light meter reading from <strong>the</strong> flower; see Adams’<br />

book The Negative for complete details on <strong>the</strong><br />

Zone System). He <strong>the</strong>n increased development<br />

to increase contrast, rendering <strong>the</strong> scene’s<br />

tones beautifully. Photoshop’s Channel Mixer,<br />

Levels and Curves controls allow digital<br />

photographers to perform similar feats.<br />

Photograph by Ansel Adams. Used by<br />

permission of <strong>the</strong> Trustees of The Ansel Adams<br />

Publishing Rights Trust. All Rights Reserved.<br />

FAR RIGHT: Ansel Adams—Tetons and Snake<br />

River. Black-and-white landscapes can be<br />

gorgeous, as <strong>the</strong> work of Ansel Adams and<br />

many o<strong>the</strong>rs demonstrates. To truly appreciate<br />

<strong>the</strong> beauty of black-and-white, try to view<br />

original prints at a gallery or museum. Adams’<br />

masterpieces were <strong>the</strong> result of a superb eye<br />

combined with complete control over<br />

technique. Today, digital photography offers<br />

tremendous control right at your desktop.<br />

Photograph by Ansel Adams. Used by<br />

permission of <strong>the</strong> Trustees of The Ansel Adams<br />

Publishing Rights Trust. All Rights Reserved.<br />

54 Outdoor Photographer<br />

&<br />

White In The<br />

Black<br />

Talented artists are always<br />

eager to embrace new<br />

technology if it has <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

to enrich <strong>the</strong>ir art and bring<br />

forth <strong>the</strong>ir vision. If he had<br />

access to today’s tools, what<br />

would Ansel Adams do?<br />

By Mike Stensvold

Digital Age<br />

More than 20 years since his passing, Ansel Adams is probably still <strong>the</strong> most widely known<br />

black-and-white outdoor photographer. He didn’t shoot digitally because digital imaging as<br />

we know it didn’t exist in those days. But I think <strong>the</strong> legendary black-and-white master would<br />

be quite interested in digital imaging were he in his shooting prime today. Adams was all for any<br />

technology that could increase his control over <strong>the</strong> image-making process, and digital imaging<br />

certainly does that. With film, Adams could adjust <strong>the</strong> exposure in camera to control <strong>the</strong> dark areas of <strong>the</strong> image,<br />

adjust development to control <strong>the</strong> light areas, and <strong>the</strong>n control <strong>the</strong> lightness or darkness of <strong>the</strong> overall print via <strong>the</strong><br />

enlarger exposure, control overall contrast by choosing <strong>the</strong> printing paper grade, and dodge and burn to make local<br />

areas of <strong>the</strong> print brighter or darker. He couldn’t watch <strong>the</strong> film develop, he had to watch <strong>the</strong> print develop by <strong>the</strong><br />

light of a dim safelight, and he had to wait for <strong>the</strong> print to wash and dry before he could see what he had.<br />

With digital imaging, you can adjust brightness and darkness, overall contrast and local contrast, in precise and<br />

repeatable increments, and even apply colored-filter effects and see <strong>the</strong> results on screen in real time—no waiting,<br />

no wasted paper, no smelly chemicals (Adams, <strong>the</strong> environmentalist, would appreciate that) and no dark required.<br />

March 2007 55

Here’s <strong>the</strong> original color shot of a<br />

great blue heron ordering breakfast.<br />

Photo by Mike Stensvold.<br />

The final black-and-white image is much stronger than a straight desaturated image.<br />

Visualization<br />

Along with his celebrated technical expertise, Adams was<br />

renowned for his creative eye. No matter what camera or<br />

medium you use, you need good subjects in good light, interestingly<br />

composed.<br />

Adams imagined what each print would look like before<br />

he exposed his film. He exposed, processed and printed his<br />

negatives to present to <strong>the</strong> viewer what he saw and felt that<br />

made him take <strong>the</strong> shot in <strong>the</strong> first place. This is one key to<br />

understanding Adams’ work: visualization—seeing <strong>the</strong> image<br />

in his mind’s eye before he made <strong>the</strong> shot.<br />

Okay, you saw something that moved you to make a photograph.<br />

How do you turn <strong>the</strong> image on your memory card<br />

into what Adams termed an expressive print that shows <strong>the</strong><br />

viewer what you saw and felt when you shot it? Let’s look at<br />

how you can apply a little Ansel to your digital photography.<br />

Adams shot mainly in black-and-white because that’s how<br />

he “saw” images and because black-and-white offered him<br />

56 Outdoor Photographer<br />

Clicking on <strong>the</strong> Red<br />

channel gives a result<br />

similar to shooting <strong>the</strong><br />

original image through<br />

a red filter—still not<br />

quite right.<br />

more control over his images than color. Today, digital imaging<br />

offers <strong>the</strong> advantage of tremendous control over both<br />

black-and-white and color images.<br />

Getting Black-And-White<br />

You can get black-and-white digital images by shooting<br />

<strong>the</strong>m that way in-camera or by converting color images to<br />

monochrome in <strong>the</strong> computer via your image-editing software.<br />

Shooting in monochrome mode, you’re working in blackand-white<br />

from <strong>the</strong> start, and <strong>the</strong> images you see on <strong>the</strong> camera’s<br />

LCD monitor will be in black-and-white, making it easier<br />

to think in black-and-white. This can be a useful way of learning<br />

to see black-and-white images.<br />

If you shoot RAW images ra<strong>the</strong>r than JPEGs, you’ll have<br />

more and better material to work with in <strong>the</strong> computer, including<br />

richer tonality in highlights and dark tones. You can doubleprocess<br />

a RAW image, once for <strong>the</strong> highlights and once for<br />

<strong>the</strong> dark areas, <strong>the</strong>n combine <strong>the</strong> two perfectly registered images

Using <strong>the</strong> Channel Mixer, you can adjust <strong>the</strong> lightness and darkness of<br />

<strong>the</strong> red, green and blue tones individually. Here, moving <strong>the</strong> Red slider to<br />

+66%, <strong>the</strong> Green slider to +20% and <strong>the</strong> Blue slider to +28% resulted in<br />

a better black-and-white image.<br />

Moving <strong>the</strong> middle of <strong>the</strong> curve up slightly brightened <strong>the</strong> midtones and<br />

moving <strong>the</strong> bottom portion down slightly produced richer dark tones.<br />

in Photoshop to get a greater range of detail. And RAW images<br />

can be processed to color or black-and-white—you’re not locked<br />

in to one or <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r. Adams would have shot RAW.<br />

If you choose to shoot your black-and-white digital images<br />

in color, <strong>the</strong>re are some advantages. You can use different colorto-monochrome<br />

conversion techniques to achieve different<br />

results and even do multiple conversions. You also can apply<br />

infinite color filtration after <strong>the</strong> fact (see <strong>the</strong> Filters sidebar).<br />

If you’re shooting in <strong>the</strong> RAW format and using <strong>the</strong> camera<br />

manufacturer’s RAW converter, simply select Monochrome<br />

in <strong>the</strong> conversion software. Doing so is effectively <strong>the</strong> same<br />

as shooting images in monochrome mode in-camera. If you’re<br />

using a third-party RAW converter, <strong>the</strong> color-to-monochrome<br />

conversion process is more complicated, but often gives you<br />

more control. I prefer to do <strong>the</strong> color-to-monochrome conversion<br />

in Photoshop, after converting <strong>the</strong> RAW image to<br />

TIFF format in <strong>the</strong> RAW converter.<br />

In Photoshop, <strong>the</strong> simplest conversion methods are changing<br />

<strong>the</strong> mode to Grayscale (Image > Mode > Grayscale) or moving<br />

<strong>the</strong> saturation slider all <strong>the</strong> way to <strong>the</strong> left (Image > Adjustments<br />

> Hue/Saturation). These methods offer very little flexibility<br />

and are rarely <strong>the</strong> best ways to convert color images.<br />

A better method is to use <strong>the</strong> Channels palette. Click on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Red, Green and Blue channels individually to see which<br />

Calibrating Your System<br />

If you want your prints to look like what you see on your screen,<br />

make sure your monitor and printer are properly calibrated in terms<br />

of color rendition and contrast. This is easily done with a colorcalibrating<br />

device such as <strong>Datacolor</strong> ColorVision Spyder2 Suite,<br />

Pantone Huey or X-Rite Eye-One. Follow <strong>the</strong> easy instructions that<br />

accompany <strong>the</strong> device and calibrate regularly every few months.<br />

Moving <strong>the</strong> top-left Levels slider to <strong>the</strong> right produced a better black<br />

tone. The top-right slider was left where it was to avoid blowing out<br />

<strong>the</strong> highlights.<br />

Black-and-White Inkjet Printing<br />

Not long ago, you pretty much had to use special black-andwhite<br />

inks to make excellent black-and-white prints with an<br />

inkjet printer, and this is still <strong>the</strong> way to go with older printers. In<br />

fact, a number of photographers have a second printer dedicated<br />

to black-and-white printing.<br />

With more and better inks, smaller ink droplets and better drivers,<br />

today’s inkjet photo printers from Canon, Epson and HP—especially<br />

<strong>the</strong> larger-format models—do an excellent job with black-and-white.<br />

These devices can turn out full-tonal-range prints with no colorcasts<br />

(unless you deliberately create a toned print).<br />

While any self-respecting aspiring Ansel Adams will do his or her<br />

own printing, <strong>the</strong>re are some excellent digital labs out <strong>the</strong>re for those<br />

who choose to have someone else make <strong>the</strong>ir prints. Check out<br />

“Working With A Lab” (Jan./Feb. 2007) on <strong>the</strong> OP Website, www.<br />

outdoorphotographer.com.<br />

looks best. If one looks <strong>the</strong> way you want, go to Image ><br />

Mode > Grayscale. This method mimics <strong>the</strong> effects of shooting<br />

a black-and-white image through a red, green or blue filter<br />

(see <strong>the</strong> Filters sidebar).<br />

Probably <strong>the</strong> most versatile way to convert color images to<br />

black-and-white is by using <strong>the</strong> Channel Mixer (Image > Adjustments<br />

> Channel Mixer, <strong>the</strong>n click <strong>the</strong> Monochrome box). This<br />

provides lots of control over <strong>the</strong> resulting tones, but requires a<br />

lot of playing. Remember that <strong>the</strong> Red channel makes red<br />

tones lighter as <strong>the</strong> slider is moved to <strong>the</strong> right and darker as<br />

it’s moved to <strong>the</strong> left; likewise for <strong>the</strong> Green and Blue channels.<br />

A good rule of thumb is to make sure <strong>the</strong> percentages of<br />

red, green and blue combined equal 100 percent, although some<br />

images might work better with a higher combined percentage<br />

(for a brighter image) or a lower combined percentage (for a<br />

darker image). The new Photoshop CS3’s Channel Mixer even<br />

includes black-and-white presets to get you started.<br />

Handy Digital Darkroom Tools<br />

Photoshop contains lots of tools, but you only need a few<br />

of <strong>the</strong>m to optimize a black-and-white photograph. Here are<br />

<strong>the</strong> best ones to use.<br />

Levels. Generally, it’s best to begin work on a digital image<br />

by setting its black and white points using <strong>the</strong> Levels control.<br />

This is especially important for black-and-white. Adams said in<br />

his book The Print that “…a note of pure white or solid black<br />

can serve as a ‘key’ to o<strong>the</strong>r values…but <strong>the</strong>re is no reason why<br />

<strong>the</strong>y must be included in all images, any more than a composition<br />

for <strong>the</strong> piano must include <strong>the</strong> full range of <strong>the</strong> eightyeight<br />

notes of <strong>the</strong> keyboard.” In short, set <strong>the</strong> black and white<br />

points to suit <strong>the</strong> image you visualized when you shot <strong>the</strong> photo.<br />

A good starting point for Levels (Image > Adjustments ><br />

Levels) is to move <strong>the</strong> upper left and right sliders in to <strong>the</strong><br />

March 2007 57

edges of <strong>the</strong> histogram to turn <strong>the</strong> brightest and darkest pixels<br />

in <strong>the</strong> image pure white and pure black. Press <strong>the</strong> Alt/Option<br />

key as you do this to see where <strong>the</strong> blacks and whites actually<br />

are in <strong>the</strong> image. The Levels histogram is a good reference,<br />

but your eye should remain <strong>the</strong> ultimate arbiter: Do what<br />

looks right. Most images work best if <strong>the</strong>y include a pure black<br />

tone and a pure white tone, but some don’t.<br />

Curves. Adams used different developers and development<br />

techniques to adjust <strong>the</strong> midtones and contrast of his<br />

images. In Photoshop, this is best done with <strong>the</strong> Curves control<br />

(Image >Adjustments > Curves). Moving <strong>the</strong> middle of<br />

<strong>the</strong> curve up makes <strong>the</strong> midtones lighter, while moving it<br />

down makes <strong>the</strong> middle tones darker.<br />

If you click on <strong>the</strong> lower portion of <strong>the</strong> curve, you can adjust<br />

that separately: Moving it down makes <strong>the</strong> dark tones darker,<br />

moving it up makes <strong>the</strong> dark tones lighter. Likewise, click on<br />

<strong>the</strong> upper portion of <strong>the</strong> curve, and you can move that portion<br />

Filters<br />

When you shoot a scene in color, <strong>the</strong> colors make or break <strong>the</strong> shot. When you shoot<br />

in black-and-white, <strong>the</strong> black, white and gray tones make or break <strong>the</strong> shot. In<br />

black-and-white, those lovely red roses that stood out so dramatically from those green<br />

leaves in real life will blend toge<strong>the</strong>r as middle gray tones in <strong>the</strong> photo. As a digital blackand-white<br />

photographer, you can examine <strong>the</strong> monochrome image on your camera’s<br />

LCD monitor right after you shoot it and see if <strong>the</strong> tones of different-colored objects merge.<br />

Ansel Adams, like most black-and-white landscape photographers, used colored filters<br />

to separate tones in his images. Digital photographers can do <strong>the</strong> same—in fact, a<br />

number of digital cameras have built-in digital colored filters.<br />

The basic concept behind using colored filters for black-and-white photography is that<br />

a filter will lighten tones of its own and similar colors and darken tones of its complementary<br />

color in <strong>the</strong> resulting photograph. The most popular colored filters used by blackand-white<br />

outdoor photographers include yellow, red and green.<br />

Yellow and red filters render a blue sky darker than it would appear in an unfiltered<br />

shot, which is useful when you want white cloud buildups to stand out strongly against<br />

a dark sky. A red filter renders red flowers lighter and green leaves darker, which is handy<br />

for shots of foliage, where <strong>the</strong> red flowers and green leaves, both reflecting about <strong>the</strong><br />

same amount of light, would appear about <strong>the</strong> same shade of gray in an unfiltered photo<br />

(you also could use a green filter to get darker flowers against lighter leaves).<br />

58 Outdoor Photographer<br />

Black-and-white<br />

conversion via Photoshop’s<br />

Channel Mixer.<br />

Original color landscape.<br />

Photo by Rob Sheppard.<br />

up to make <strong>the</strong> light tones lighter or down to make <strong>the</strong>m darker.<br />

You can click multiple times on <strong>the</strong> curve itself to add anchor<br />

points, but one in <strong>the</strong> middle of <strong>the</strong> curve and one at <strong>the</strong> middle<br />

of <strong>the</strong> lower section and <strong>the</strong> upper section usually will suffice.<br />

A tip: A little movement of <strong>the</strong> curve goes a long way.<br />

Shadow/Highlight. This control (Image > Adjustments ><br />

Shadow/Highlight) can bring out amazing amounts of detail in<br />

underexposed dark areas and overexposed bright ones. It can<br />

help open dark midtones if used carefully. The default Shadow<br />

setting of 50 percent is usually too strong; try 30 percent as a<br />

starting point.<br />

Layers. Photoshop’s layers and layer masks are features<br />

Adams would have loved. Layers allow you to make each<br />

change to your image independent of o<strong>the</strong>r changes and make<br />

it easy to keep track of <strong>the</strong>m. Even more important, layers let<br />

you make changes nondestructively, without affecting <strong>the</strong><br />

image’s pixels. None of <strong>the</strong> changes you make is applied to<br />

<strong>the</strong> image pixels until you flatten <strong>the</strong> image<br />

(Layer > Flatten Image) when you’re done;<br />

thus, <strong>the</strong>re’s only one change applied to <strong>the</strong><br />

pixels instead of lots of changes individually.<br />

Adjustment layers (Layer > New Adjustment<br />

Layer) let you do Levels, Curves and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r corrections. Duplicate Layers (Layer ><br />

Duplicate Layer) allow you to do just about<br />

anything without affecting <strong>the</strong> original pixels.<br />

A good layer workflow might be:<br />

� Open <strong>the</strong> original image and save it as<br />

a TIFF or PSD working copy.<br />

� Create a Levels adjustment layer (Layer<br />

> New Adjustment Layer > Levels) and set<br />

<strong>the</strong> black and white points.<br />

� Create a Curves adjustment layer and<br />

adjust <strong>the</strong> middle tones.<br />

� Use Photoshop’s Dodge and Burn tools<br />

to adjust local contrast or do it via additional<br />

layers and layer masks, as described below.

Original photograph of<br />

paintbrush scene. Photo by<br />

Rob Sheppard.<br />

Using Photoshop’s Channel<br />

Mixer to do <strong>the</strong> conversion<br />

allows <strong>the</strong> photographer to<br />

adjust each primary color’s<br />

gray rendition individually,<br />

resulting in a black-and-white<br />

image with more impact.<br />

Software For B&W<br />

The camera manufacturers’ RAW-conversion software provides<br />

basic conversion capabilities and sometimes more—Nikon’s Capture<br />

NX is a good example. Current versions of Photoshop and Photoshop<br />

Elements come with Adobe’s versatile Camera Raw RAW-image<br />

converter, and it also can be purchased as a stand-alone. O<strong>the</strong>r good<br />

RAW converters can be found in Apple’s Aperture, Phase One’s Capture<br />

One, DxO’s Optics Pro, Digital Light & Color’s Picture Window<br />

and <strong>the</strong> B/W Conversion Filters in Nik Software’s Color Efex Pro 2.0.<br />

There’s also a number of plug-ins for Photoshop (and applications<br />

that use Photoshop-compatible plug-ins) that provide blackand-white<br />

photographers with useful tools. Among <strong>the</strong>m are Alien<br />

Skin’s Exposure, B/W Styler for Windows from The Plug-In Site and<br />

Black & White Studio from Power Retouche.<br />

Layer Masks. Layer masks let you apply changes to selected<br />

portions of an image ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> entire image. When you<br />

create an adjustment layer, Photoshop automatically creates<br />

a corresponding layer mask. Layer masks make it easy to<br />

do what Adams did by dodging and burning. For example,<br />

to darken a specific area of <strong>the</strong> image, create a Brightness/<br />

Contrast adjustment layer (Layer > New Adjust-<br />

ment Layer > Brightness/Contrast) and move<br />

<strong>the</strong> brightness layer to <strong>the</strong> left to a setting of<br />

-20 or -25. This turns <strong>the</strong> whole image darker.<br />

Painting black on a layer mask conceals or<br />

hides <strong>the</strong> layer’s effect, so <strong>the</strong> adjustment isn’t<br />

applied to those areas. Painting white on <strong>the</strong><br />

layer mask reveals <strong>the</strong> effect below, so <strong>the</strong><br />

layer’s adjustment is applied to those areas of<br />

<strong>the</strong> image. In our example, you can fill <strong>the</strong><br />

darkening layer with black to hide its effect<br />

(Edit > Fill, choose Black) and <strong>the</strong>n use a white<br />

Brush tool to paint over (reveal) <strong>the</strong> areas where<br />

you want <strong>the</strong> effect (darkening) to be applied.<br />

We don’t have room to go deeply into layer<br />

masks, but you can learn all about <strong>the</strong>m at <strong>the</strong><br />

OP Website (www.outdoorphotographer.com).<br />

Resources<br />

Adobe<br />

(800) 833-6687<br />

www.adobe.com<br />

Alien Skin Software<br />

(888) 921-SKIN<br />

www.alienskin.com<br />

Apple Computer<br />

(800) MY-APPLE<br />

www.apple.com<br />

Canon<br />

(800) OK-CANON<br />

www.usa.canon.com<br />

<strong>Datacolor</strong> ColorVision<br />

(800) 554-8688<br />

www.colorvision.com<br />

Finishing Touches<br />

Once you have <strong>the</strong> tones of <strong>the</strong> image as you want <strong>the</strong>m,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re’s one more step Adams considered important. You want<br />

to keep <strong>the</strong> viewer’s eye in <strong>the</strong> frame, and bright areas near<br />

<strong>the</strong> edges draw <strong>the</strong> eye out of <strong>the</strong> frame. So Adams burned in<br />

<strong>the</strong> edges of his prints, darkening <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

You can do this in Photoshop. An easy way is to create a<br />

Brightness/Contrast Adjustment layer, darken <strong>the</strong> entire layer<br />

by moving <strong>the</strong> Brightness slider to a minus number (again,<br />

-20 or -25 is a good starting point) and fill <strong>the</strong> layer with<br />

black to hide <strong>the</strong> darkening. Then, using a large, soft brush,<br />

paint white over <strong>the</strong> edges of <strong>the</strong> image, revealing <strong>the</strong> layer’s<br />

darkening effect. OP<br />

For more details on producing digital images, check out<br />

OP Editor Rob Sheppard’s book Outdoor Photographer<br />

Landscape and Nature Photography with Photoshop CS2,<br />

which provides information for <strong>the</strong> digital nature photographer,<br />

including a whole chapter entitled “What Would<br />

Ansel Do?”<br />

Digital Light & Color<br />

(617) 489-8858<br />

www.dl-c.com<br />

DxO<br />

www.dxo.com<br />

Epson<br />

(800) GO-EPSON<br />

www.epson.com<br />

Hewlett-Packard (HP)<br />

(800) 752-0900<br />

www.hp.com<br />

Nikon<br />

(800) NIKON-UX<br />

www.nikonusa.com<br />

Nik Software<br />

(619) 725-3150<br />

www.niksoftware.com<br />

Pantone<br />

(201) 935-5500<br />

www.pantone.com<br />

Phase One<br />

www.phaseone.com/photo<br />

The PlugIn Site<br />

www.<strong>the</strong>pluginsite.com<br />

Power Retouche<br />

www.powerretouche.com<br />

X-Rite<br />

(914) 347-3300<br />

www.xritephoto.com<br />

OP ON THE WEB<br />

WWW.OUTDOORPHOTOGRAPHER.COM<br />

See: “Shooting Digital For B&W” (Sept. ’06)<br />

March 2007 59