Newsletter 4 - Marine Mammal Institute - Oregon State University

Newsletter 4 - Marine Mammal Institute - Oregon State University

Newsletter 4 - Marine Mammal Institute - Oregon State University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

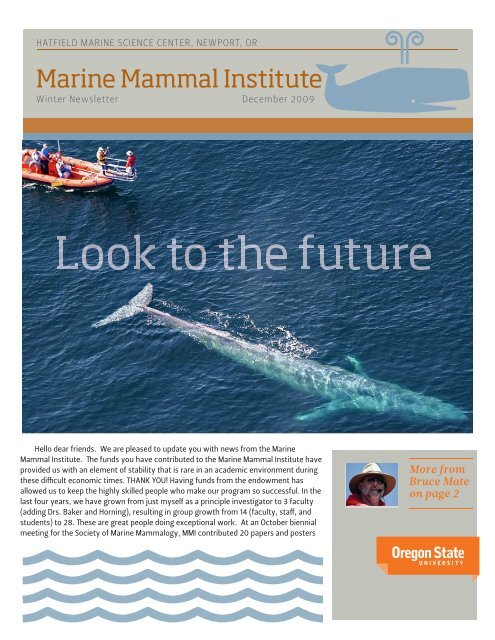

HATFIELD MARINE SCIENCE CENTER, NEWPORT, OR<br />

<strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> <strong>Institute</strong><br />

Winter <strong>Newsletter</strong> December 2009<br />

Look to the future<br />

Hello dear friends. We are pleased to update you with news from the <strong>Marine</strong><br />

<strong>Mammal</strong> <strong>Institute</strong>. The funds you have contributed to the <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> have<br />

provided us with an element of stability that is rare in an academic environment during<br />

these difficult economic times. THANK YOU! Having funds from the endowment has<br />

allowed us to keep the highly skilled people who make our program so successful. In the<br />

last four years, we have grown from just myself as a principle investigator to 3 faculty<br />

(adding Drs. Baker and Horning), resulting in group growth from 14 (faculty, staff, and<br />

students) to 28. These are great people doing exceptional work. At an October biennial<br />

meeting for the Society of <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong>ogy, MMI contributed 20 papers and posters<br />

More from<br />

Bruce Mate<br />

on page 2

during the one week of workshops and formal presentations.<br />

More and more, MMI is recognized for its many worldwide<br />

academic collaborations and agency funding diversity,<br />

including the National <strong>Marine</strong> Fisheries Service (NMFS), Minerals<br />

Management Service (MMS), the Department of Energy<br />

(DOE), National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Department<br />

of Defense (DOD). I hope you are as proud as I am in the<br />

accomplishments we have achieved with your support!<br />

MMI is dedicated to becoming the international center of<br />

academic excellence in marine mammal ecology, conservation<br />

and ocean health. To a growing extent the university is<br />

encouraging collaborative studies as a means of reducing<br />

expenses and increasing efficiency. This is something MMI is<br />

trying to do by attracting shared positions with many OSU<br />

colleges so that new faculty can work in close proximity to<br />

one another to solve the complicated challenges our society<br />

places on marine resources. Regrettably, space is in such a<br />

premium at the Hatfield <strong>Marine</strong> Science Center, there is “no<br />

room at the inn”. In that regard, we have renewed our federal<br />

proposal to the National <strong>Institute</strong> of Standards and Technology<br />

(NIST) for a new building in Newport. Our previous effort,<br />

which required a $9 M non-federal match to acquire $14 M of<br />

federal funding, came apart during the last week of the <strong>Oregon</strong><br />

legislative session (which meets only 6 months every 2 years).<br />

There will be a short legislative session in February and we are<br />

hoping to acquire the needed match during that session to be<br />

eligible for the NIST grant (awards announced in March 2010).<br />

Besides MMI, the building would house the <strong>Marine</strong> Genomics<br />

and Genomics Program, and a proposed <strong>Marine</strong> Biodiscovery<br />

program looking for medical cures from marine organisms,<br />

including chemosynthetic species around deep-sea thermal<br />

vents.<br />

Things here have been busy and I want to bring you up to<br />

date on many exciting happenings.<br />

The Whale Telemetry Group (WTG) has been tagging<br />

eastern gray whales this fall along the central <strong>Oregon</strong> coast.<br />

Because gray whales are a<br />

near-shore species, we did<br />

this as a day-trip operation,<br />

trailering our 22' boat from<br />

port to port and over-nighting<br />

in hotels. Ladd Irvine, a<br />

recent COAS Masters student<br />

of mine, has been doing the<br />

tagging. Barb Lagerquist, a<br />

former MMI-Masters student<br />

in Fisheries & Wildlife, used to<br />

be our lead field person before<br />

getting married and having<br />

two children. Because we were<br />

“local”, she was able again to<br />

drive the boat during approaches and has not lost her touch. It<br />

is good to have her back in a field mode. Craig Hayslip (MS from<br />

U of WA) has been our main photographer for several years and<br />

is an important part of this project because we are using photos<br />

Territorial Seas Work<br />

The R/V Pacific Storm was engaged for 3 months, 24/7 this<br />

summer in measuring the <strong>Oregon</strong> Territorial seas as part of a<br />

College of Oceanic & Atmospheric Sciences program. It really paid<br />

its own way. It surveyed the nearshore sea floor to improve maps<br />

originally created over 60 years ago. The crew operated with<br />

a precise satellite GPS system that even took into the account<br />

the role of the vessel and state of the tide to identify the precise<br />

water depth.<br />

to evaluate the effects of tagging over time. Tomas Follett, our<br />

database manager, loves getting out into the field, but gets<br />

“chained to a desk” most of the time. In this field season he<br />

got to get out into the field and gain boat-driving experience.<br />

Jennifer Olson, and intern this fall from Colorado, has been<br />

taking biopsy samples and processing them. It takes five folks<br />

to tag whales. I only got out with them one day. They did such<br />

a great job, that they no longer “need” me out there. I am<br />

proud of them, but “Darn, I kind of liked that part myself”!<br />

When we are all out doing field work or at meetings, the office<br />

work is ably managed by Sheri Woods, Bonnie Anderson-<br />

Becktold, and Kathy Minta, who keep our many universitybased<br />

operations working smoothly.<br />

These animals, which were thought to be resident all<br />

throughout the summer/fall-feeding season moved around<br />

a great deal and very quickly. Within two weeks one animal<br />

was halfway up Vancouver Island, while another was in<br />

northern California. Virtually all the animals were identified<br />

from photographs so we have a known sighting history that<br />

goes back up to 15 years. Some of their movements this fall<br />

have tracked individuals to every area they have ever been<br />

sighted in throughout their entire lifetime. This is the first time<br />

we have tagged whales off <strong>Oregon</strong> and the reason was to test<br />

a new generation of tags that we may be using next year for<br />

the tagging of Western Gray whales off Sakhalin Island, Russia.<br />

I have gone to the International Whaling Commission meetings<br />

the last four years, in part to gain endorsements from the<br />

international community about tagging this most highly<br />

endangered species (relative to the gray whales along our<br />

coast). They were thought to be extinct in the 1970’s and now<br />

MMI <strong>Newsletter</strong> December 2009 2 OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

number just 130 animals. Amazingly, we do<br />

not know where these animals go to breed<br />

and calve in the winter. Identifying that<br />

will aid conservation efforts and promote<br />

the recovery of this fragile population,<br />

who’s summer feeding habitat is an area of<br />

developing oil and gas production.<br />

Robyn Matteson did an outstanding<br />

job of defending her master’s thesis in<br />

oceanography recently. She collected<br />

and assembled the oceanographic data<br />

associated with blue whale concentrations<br />

at the Costa Rica Dome (CRD), during our<br />

spectacular cruise on the Pacific Storm<br />

800 miles west of Costa Rica in 2008. I<br />

hope you had an opportunity to see the<br />

2-hour National Geographic documentary<br />

which first<br />

aired in March,<br />

entitled<br />

“Kingdom<br />

of the Blue<br />

Whale”. It<br />

has received<br />

the highest rating of any program that has<br />

ever aired on the channel. The companion<br />

article in the March National Geographic<br />

magazine (“Still Blue”) is also the highest<br />

rated piece for this year’s issue. Not<br />

only did we identify the first calving area<br />

for blue whales anywhere in the world,<br />

they were also feeding and mating. Our<br />

collaborator, John Calambokidis maintains<br />

an extensive catalog of blue whales<br />

found in the eastern North Pacific and<br />

photographed untagged whales at the<br />

CRD. Most of the photos from the CRD did<br />

not match his catalog, which is thought to<br />

encompass at least 80 % of the west coast<br />

population. Thus, whales using the CRD<br />

to breed and calve also come from other<br />

areas, probably the central and western<br />

North Pacific. I would very much like to<br />

return to the CRD to tag whales and track<br />

them to these other feeding areas. We are<br />

also planning on how to do additional blue<br />

whale research in the winter off the Pacific<br />

coast of Baja, Mexico, where this may also<br />

be happening.<br />

During the NG-sponsored research,<br />

we encountered a dead blue whale floating<br />

in the western Santa Barbara channel. We<br />

helped perform a dissection, which showed<br />

it had been struck by a ship. This was one<br />

of 5 deaths of these remarkable animals<br />

reported in just 3 weeks in southern<br />

California. MMI tagging data help<br />

understand the seasonal distributions<br />

of whales and will suggest ways to<br />

reduce blue whale mortalities from<br />

ship strikes. Such research provides<br />

insights into how small changes in<br />

human activities can often make a<br />

big difference in the conservation and<br />

recovery of endangered species.<br />

Some of you will recall that<br />

MMI provided seed funding for Kelly<br />

Benoit-Bird in COAS to begin work<br />

with squid in the Gulf of California with<br />

Bill Gilly from Stanford <strong>University</strong>. This<br />

work provided a basis for our research<br />

on squid-eating<br />

Small changes in human activities<br />

can often make a big difference to<br />

the conservation and recovery of<br />

endangered species.<br />

sperm whales<br />

in the same<br />

area the next<br />

two years. As a<br />

result of those<br />

combined<br />

efforts, Kelly and Bill have received a<br />

three-year grant from NSF to further<br />

understand this elusive species and its<br />

trophic relationship to whales.<br />

This fall, MMI entered into a<br />

new collaborative relationship with<br />

the College of Engineering in which<br />

three senior students and a graduate<br />

student began working on tag<br />

development design issues as their<br />

capstone project. This collaboration<br />

with Dr. John Parmigiani and OSU<br />

alumnus Bill Reiersgaard has led to<br />

the submission of a National Ocean<br />

Partnership Program grant, which<br />

would continue these studies for two<br />

more years with additional professional<br />

involvement. Bill has been working with<br />

me for many years on tag designs. The<br />

engineering students will characterize<br />

the skin, blubber and muscle of whales,<br />

to make a synthetic testing environment<br />

out of ballistic gels (think “CSI” and the<br />

testing of bullet trajectories in flesh) and<br />

develop a virtual computer environment<br />

in which various tag designs can be<br />

modified and tested without having<br />

to put them out on a real whale. They<br />

will be using tissues collected by the<br />

<strong>Oregon</strong> <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> Stranding<br />

As you may recall, there is a great<br />

There is a great interest in<br />

harnessing wave energy off the<br />

<strong>Oregon</strong> Coast. We are examining<br />

the feasibility of using<br />

an acoustic device to protect<br />

whales if these buoy moorings<br />

become a collision hazard for<br />

the whales. Gray whales do not<br />

have any sophisticated sonar<br />

system. By emitting only low<br />

frequency sounds, they identify<br />

large features for navigation,<br />

but not smaller features like the<br />

4-6” diameter mooring cables.<br />

If problems develop with<br />

whales inadvertently running<br />

into these cables, there needs<br />

to be a way to keep them at a<br />

distance. With all the negative<br />

concerns about acoustics and<br />

whales, this may be an area<br />

where a low level of sound may<br />

actually save whale lives. Next<br />

year, we will test a device in<br />

the migration stream to see if<br />

it can divert gray whales up to<br />

500 yards. If so, this will be the<br />

first device of its sort to keep<br />

whales out of harms way from<br />

other calamities as well, like oil<br />

spills.<br />

Network (OMMSN), led by Jim Rice, the<br />

MMI stranding coordinator, who works<br />

closely with the College of Veterinary<br />

Medicine’s Veterinary Diagnostic Lab.<br />

I hope you will see the advances I<br />

have reported here and those elsewhere<br />

in this issue as an indication of what a<br />

good investment your gifts to MMI have<br />

been. I would be very grateful to have<br />

your continued support this coming<br />

year….and don’t forget us in your estate<br />

planning too!<br />

MMI <strong>Newsletter</strong> December 2009 3 OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

New Faces in MMI<br />

Alana Alexander<br />

Julia Hager<br />

Joining the <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> in May 2009 as a parttime<br />

research technician in the Pinniped Ecology Applied Research<br />

Laboratory (PEARL), Julia came with a Master’s degree<br />

in <strong>Marine</strong> Biology from Bremen, Germany. During this time<br />

she was engaged in the ecology of Antarctic ice algae and now<br />

would like to gain insights into the marine mammal research.<br />

Under the supervision of the lab head Dr. Markus Horning<br />

and the Faculty Research Assistant Kim Raum-Suryan she<br />

is involved in the study about the attendance patterns and<br />

entanglement rates of Steller sea lions at Sea Lion Caves, near<br />

Heceta Head. Additionally, Julia is preparing her PhD project<br />

which will address the sensory system of pinnipeds.<br />

Alana is an International Fulbright Science and Technology<br />

awardee (2008-2010) from New Zealand. She arrived at OSU in<br />

September 2008 after completing her BSc(Hons) degree in 2006,<br />

and then working for two years as a research assistant at The<br />

<strong>University</strong> of Auckland, New Zealand. Her BSc(Hons) dissertation<br />

focused on the low level of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)<br />

control region diversity found in long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala<br />

melas). For her PhD, Alana is extending this analysis<br />

to the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), as well as<br />

updating previous research on global and regional geneflow by<br />

sequencing longer regions of the mtDNA control region and<br />

using DNA from previously unsampled areas.<br />

Angie Sremba<br />

Angie began her career at <strong>Oregon</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>University</strong> as an intern in<br />

the 2006 Research Experience for Undergraduate (REU) program.<br />

After graduating from Kalamazoo College, Kalamazoo, Michigan in<br />

2007, she worked as a research assistant with the Cooperative<br />

<strong>Institute</strong> for <strong>Marine</strong> Resources Studies (CIMRS) to finalize the<br />

research she had begun as an intern. Before starting graduate<br />

school, she had the opportunity to participate in the winter 2008<br />

cetacean research field season with the Universidad de Baja<br />

California Sur in La Paz, Mexico. During this time, she helped with<br />

photo-identification and biopsy collection on cruises in the Gulf of<br />

California and spent two months working with gray whales<br />

(Eschrichtius robustus) in the San Ignacio Lagoon with Dr. Steven<br />

Swartz. She began her MSc with Scott Baker in the fall of 2009 working<br />

in the Cetacean Conservation and Genetics laboratory. For her<br />

MSc thesis, Angie will be studying the genetic diversity of the blue<br />

whale (Balaenoptera musculus) both in the eastern tropical North<br />

Pacific and Antarctic.<br />

MMI <strong>Newsletter</strong> December 2009 4 OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

Three large cetacean strandings<br />

occurred in <strong>Oregon</strong> this past spring<br />

Reported by Jim Rice<br />

<strong>Oregon</strong> <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> Stranding Coordinator<br />

In early April, a fresh dead adult female gray whale (Eschrichtius<br />

robustus) was found on the beach at Washburn <strong>State</strong> Park, just north of<br />

Heceta Head. She was extremely emaciated, and there was no evident<br />

trauma to the body. Her posture, lying belly-down flat on the sand,<br />

suggests that she died on the beach or in shallow water shortly before<br />

she was reported to the stranding network. We suspect the immediate<br />

cause of death was starvation. A necropsy was conducted immediately<br />

Dead gray whale found near Heceta Head<br />

and tissue samples were collected and submitted to the Veterinary<br />

Diagnostic Laboratory at OSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine in Corvallis. Pathology results determined the whale had<br />

ovarian cancer. The carcass was buried on site by the <strong>Oregon</strong> Department of Parks and Recreation the following day.<br />

On March 6, a distressed whale was sighted by Coast Guard helicopter in the surf at Heceta Beach, in Florence.<br />

Members of the <strong>Oregon</strong> <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> Stranding Network (OMMSN) responded and found the whale stuck on a sandbar<br />

and getting knocked over by waves. As the tide came in, the whale managed to free itself and began swimming again. It<br />

was observed by helicopter swimming weakly northward,<br />

parallel to the beach on the edge of the surf zone. The<br />

following day, the Coast Guard again searched the waters<br />

for the whale during their regular flyovers, but no sightings<br />

of the animal were made. Then, at approximately 5:00<br />

PM, a passerby reported a dead whale on a remote beach<br />

immediately north of Sea Lion Caves. An investigation<br />

of the carcass commenced the following morning, but<br />

by then it had been moved by the tide to its final resting<br />

place, at Devil’s Elbow <strong>State</strong> Park, adjacent to Heceta Head<br />

Lighthouse.<br />

Stranding network members spent much of Sunday<br />

examining the carcass, taking measurements, photographs,<br />

A live fin whale had stranded alive two days earlier a few miles and various tissue samples.<br />

away, but made it back into the water. It subsequently died and The whale was found to be<br />

floated to this beach at Heceta Head where it was buried.<br />

a sub-adult male fin whale<br />

(Balaenoptera physalus), with no apparent signs of injury that could immediately be ascribed<br />

as a cause of death (ship strike or fishery entanglement, for example). Its emaciated condition<br />

suggested that the whale had likely been sick for some time before coming ashore. The<br />

carcass was buried on site by the <strong>Oregon</strong> Department of Parks and Recreation on Monday,<br />

March 9. Just prior to burial, samples for archiving were collected. A thorough necropsy to<br />

determine cause of death was not conducted, as <strong>State</strong> Parks managers insisted that the<br />

carcass not be taken apart on the beach.<br />

On the stormy night of May 13, a live sperm whale calf was reported coming ashore at the<br />

base of a cliff in Depoe Bay. It was later found dead in a nearby cove with no beach access. On<br />

the following day the carcass was found floating offshore by Carrie Newell of Whale Research<br />

Excursions. She graciously brought a response team from the <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> on<br />

her zodiac to collect samples of skin, blubber, lesions, and intestine. It is believed that the<br />

calf became lost and disoriented after becoming separated from its mother. We received no<br />

reports of sightings of adult sperm whales in the area.<br />

Further details, photos and maps can be found at www.mmi.oregonstate.edu/OMMSN<br />

A sperm whale calf stranded at an<br />

inaccessible beach at Depoe Bay.<br />

MMI <strong>Newsletter</strong> December 2009 5 OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

Untangling the mystery of<br />

entangled Steller sea lions:<br />

first steps toward a solution<br />

A followup story by Kim Raum-Suryan<br />

Since 2005, we have been collecting<br />

data about Steller sea lions entangled<br />

in marine debris and derelict fishing<br />

gear off two haul-out sites in <strong>Oregon</strong>,<br />

Sea Lion Caves and Cascade Head. We<br />

noticed that many of the younger sea<br />

lions (1 to 3 years-of-age) had thick<br />

black bands around their necks. As<br />

the animals grow, these bands start<br />

cutting into the neck, eventually causing<br />

severe injury and death if the bands do<br />

not break off (very unlikely). At first,<br />

we were unsure about the source of<br />

this entangling debris. However, we<br />

realized that these black rubber bands<br />

are the same bands that are used on<br />

commercial and sport crab pots. We<br />

have subsequently found some of these<br />

bands washed up on <strong>Oregon</strong> beaches.<br />

The mystery is how these sea lions are<br />

getting these bands around their necks<br />

and what we can do to help prevent<br />

this problem. The loose ‘replacement’<br />

bands are either being lost overboard<br />

vessels at sea or the sea lions are<br />

somehow becoming entangled in the<br />

bands while on the crab pots. We<br />

suggested cutting the loops, making<br />

them into ‘strips’ so if they come off<br />

the crab pots, they lose the loop and<br />

are no longer an entanglement hazard<br />

to marine animals. Another idea is to<br />

better secure the ‘replacement’ bands<br />

while on board the vessels so they don’t<br />

accidentally go overboard and present<br />

an entanglement hazard. We contacted<br />

the <strong>Oregon</strong> Dungeness Crab Commission<br />

(ODCC) about this problem. At first, we<br />

met with resistance, that there is “no<br />

way” these bands could be coming from<br />

the commercial crab fishery. However,<br />

after observing newly entangled young<br />

sea lions each year for the past 4 years,<br />

presenting the data and photos at a<br />

meeting with the director of the ODDC,<br />

crab fishers, <strong>Oregon</strong> Department of Fish<br />

and Wildlife biologists, and <strong>Oregon</strong> Sea<br />

Grant personnel, there was a change of<br />

heart and the ODDC agreed to help us<br />

bring awareness of this issue to the crab<br />

fleet. As part of this effort, the ODCC has<br />

printed laminated copies of a photo of a<br />

Steller sea lion with a black rubber band<br />

around its neck and has listed ways crab<br />

fishers can help reduce the problem of<br />

entanglements. They plan to post these<br />

at ports throughout <strong>Oregon</strong>. They also<br />

presented our findings at the recent 2009<br />

<strong>Oregon</strong> Dungeness Crab Summit held in<br />

Newport, <strong>Oregon</strong>. We are pleased that<br />

the ODDC has agreed to help us bring<br />

awareness about this problem, but we<br />

have a long road ahead of us to solve this<br />

problem.<br />

New study of Steller sea lions<br />

suggests death by predation<br />

may be higher<br />

(Source - Mark Floyd, OSU)<br />

A pioneering project that implants lifelong<br />

monitors inside of Steller sea lions<br />

to learn more about why the number<br />

of these endangered marine mammals<br />

has been declining – and remains low<br />

in Alaska – is beginning to provide<br />

data, and the results are surprising to<br />

scientists.<br />

Four out of five of the data sets that<br />

researchers have recovered indicate that<br />

the sea lions died from traumatic causes<br />

– most likely, attack from transient killer<br />

whales.<br />

This comes as a surprise to many<br />

scientists and resource managers who<br />

previously thought that recent sea lion<br />

population trends are largely attributable<br />

to depressed birth rates, a loss of<br />

fecundity, or poor nutrition, according<br />

to Markus Horning, a pinniped specialist<br />

with the <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> <strong>Institute</strong> at<br />

<strong>Oregon</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>University</strong> and principal<br />

investigator in the study.<br />

“This obviously is a very small sample<br />

so we cannot overstate our conclusions,”<br />

Horning said, “but the fact that four<br />

out of five deceased Steller sea lions<br />

that we received data from met with a<br />

sudden, traumatic<br />

death is well beyond<br />

what conventional<br />

thought would have<br />

predicted. It could<br />

be coincidence…or<br />

it could mean that<br />

predation is a much<br />

more important factor<br />

than has previously<br />

been acknowledged.”<br />

Results of the<br />

study are being<br />

published in the<br />

journal Endangered Species Research<br />

and results were presented at a meeting<br />

of the Society for <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong>ogy in<br />

Quebec City.<br />

The science behind the discovery<br />

is a story within itself. The researchers<br />

worked with Wildlife Computers, Inc., in<br />

Redmond, Wash., to develop a tag that<br />

could be implanted in the body cavity of<br />

sea lions and remain there during their<br />

life span. Conventional externally applied<br />

tags rarely have the battery power to<br />

transmit data for longer than a year and<br />

are shed during the annual molt – thus<br />

information about sea lion mortality is<br />

difficult to obtain.<br />

These new tags, however, stay<br />

within the sea lion until its death,<br />

recording temperatures for as long as<br />

eight to 10 years. When an animal dies,<br />

and either decomposes or is torn apart<br />

by predators, the tags are released and<br />

send a signal to a satellite that transmits<br />

it to Horning’s lab at OSU’s Hatfield<br />

<strong>Marine</strong> Science Center in Newport, Ore.<br />

“We can tell whether an animal died<br />

by acute death through the temperature<br />

change rate sensed by the tags and<br />

whether the subsequent transmission of<br />

a signal is immediate or delayed,” said<br />

Horning, who is an assistant professor of<br />

fisheries and wildlife at OSU.<br />

Horning and his collaborator, Jo-<br />

Ann Mellish, have tested cooling and<br />

decomposition rates of sea lions on<br />

animals that have died from stranding or<br />

other causes. They’ve also inserted tags<br />

within those animals to see how long<br />

it would take before the signal would<br />

transmit based on whether an animal<br />

was on the beach, was deep at sea, or<br />

was torn apart by predators.<br />

continued on page 7<br />

MMI <strong>Newsletter</strong> December 2009<br />

6 OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

Their protocol for inserting tags<br />

within live Steller sea lions was<br />

developed from initial deployments on<br />

non-threatened, stranded California<br />

sea lions at the <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> Center<br />

in Sausalito, Calif.<br />

“We wanted to make sure<br />

there was no adverse impact on the<br />

animals,” Horning said, “and there<br />

wasn’t.” Since 2005, Horning and<br />

his colleagues at the Alaska Sea Life<br />

Center in Seward have implanted<br />

tags into 27 Steller sea lions that were<br />

captured and released off the coast<br />

of Alaska. Since that time, they have<br />

received data from five animals – at<br />

least four of which appeared to die<br />

from traumatic deaths, based on the<br />

rate of tag cooling and immediate<br />

signal transmission. Horning said the<br />

tags can precisely identify the moment<br />

an animal died from temperature<br />

data. And while they are confident<br />

in their ability to determine whether<br />

the death was caused by predation<br />

or non-traumatic causes, identifying<br />

the actual predator is admittedly a bit<br />

of guesswork, Horning says. “There<br />

are only a couple of species that are<br />

known to target sea lions as prey,”<br />

he pointed out. “Orcas are not only<br />

common in that region of Alaska, they<br />

also have been observed preying on<br />

sea lions. Some species of sharks are<br />

known to attack sea lions, but they<br />

aren’t as common in those waters and<br />

there haven’t been any observations<br />

of predation in the study area.” If<br />

predation of Steller sea lions is more<br />

prevalent than previously thought,<br />

Horning said, there are implications for<br />

management. “If the proportion of sea<br />

lions killed by predation in our study<br />

was applied to population models,<br />

we estimate that more than half of<br />

the female Steller sea lions would be<br />

consumed by predators before they<br />

have a chance to reproduce,” Horning<br />

said. “We recognize that this is a very<br />

coarse estimate based on a small<br />

sample size. “But we hope this serves<br />

as a wakeup call to begin looking more<br />

closely into the actual role of predation<br />

as a determinant in Steller sea lion<br />

populations.”<br />

These newly developed tags were also featured<br />

in a brief newsclip in the Oct 23 2009 issue of<br />

the journal SCIENCE (Vol. 326, p. 505).<br />

‘Bycatch’ whaling — a growing threat to coastal whales<br />

(Source - Science News - June 29, 2009)<br />

Scientists are warning that a<br />

new form of unregulated whaling has<br />

emerged along the coastlines of Japan<br />

and South Korea, where the commercial<br />

sale of whales killed as fisheries<br />

“bycatch” is threatening coastal stocks<br />

of minke whales and other protected<br />

species.<br />

Scott Baker, associate director of the<br />

<strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> <strong>Institute</strong><br />

at <strong>Oregon</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>University</strong>,<br />

says DNA analysis of whalemeat<br />

products sold in<br />

Japanese markets suggests<br />

that the number of whales<br />

actually killed through this<br />

“bycatch whaling” may<br />

be equal to that killed through Japan’s<br />

scientific whaling program – about 150<br />

annually from each source.<br />

Baker, a cetacean expert,<br />

and Vimoksalehi Lukoscheck of<br />

the <strong>University</strong> of California-Irvine<br />

presented their findings at the<br />

recent scientific meeting of the<br />

International Whaling Commission<br />

(IWC) in Portugal. Their study found that<br />

nearly 46 percent of the minke whale<br />

products they examined in Japanese<br />

markets originated from a coastal<br />

population, which has distinct genetic<br />

characteristics, and is protected by<br />

international agreements.<br />

Their conclusion: As many as<br />

150 whales came from the coastal<br />

population through commercial bycatch<br />

whaling, and another 150 were taken<br />

from an open ocean population through<br />

Japan’s scientific whaling. In some past<br />

years, Japan only reported about 19<br />

minke whales killed through bycatch,<br />

though that number has increased<br />

recently as new regulations governing<br />

commercial bycatch have been adopted,<br />

Baker said.<br />

Japan is now seeking IWC agreement<br />

to initiate a small coastal whaling<br />

program, a proposal which Baker says<br />

should be scrutinized carefully because<br />

of the uncertainty of the actual catch<br />

and the need to determine appropriate<br />

population counts to sustain the distinct<br />

stocks.Whales are occasionally killed<br />

in entanglements with fishing nets and<br />

the deaths of large whales are reported<br />

by most member nations of the IWC.<br />

Japan and South Korea are the only<br />

countries that allow the commercial<br />

sale of products killed as “incidental<br />

bycatch.” The sheer number of whales<br />

represented by whale-meat products on<br />

the market suggests that both countries<br />

have an inordinate amount of bycatch,<br />

Baker said.“The sale<br />

of bycatch alone<br />

supports a lucrative<br />

trade in whale meat<br />

at markets in some<br />

Korean coastal<br />

cities, where the<br />

wholesale price of<br />

an adult minke whale can reach as high<br />

as $100,000,” Baker said. “Given these<br />

financial incentives, you have to wonder<br />

how many of these whales are, in fact,<br />

killed intentionally.”<br />

In Japan, whale-meat products<br />

enter into the commercial supply chain<br />

that supports the nationwide distribution<br />

of whale and dolphin products for<br />

human consumption, including products<br />

from scientific whaling. However, Baker<br />

and his colleagues have developed<br />

genetic methods for identifying the<br />

species of whale-meat products and<br />

determining how many individual<br />

whales may actually have been killed.<br />

Baker said bycatch whaling also<br />

serves as a cover for illegal hunting, but<br />

the level at which it occurs is unknown.<br />

In January 2008, Korean police launched<br />

an investigation into organized illegal<br />

whaling in the port town of Ulsan, he<br />

said, reportedly seizing 50 tons of minke<br />

whale meat.<br />

Other protected species of large<br />

whales detected in market surveys<br />

include humpbacks whales, fin whales,<br />

Bryde’s whales and critically endangered<br />

western gray whales. The entanglement<br />

and death of western or Asian gray<br />

whales is of particular concern given the<br />

extremely small size of this endangered<br />

populations, which is estimated at only<br />

100 individuals.<br />

It will be published in a forthcoming<br />

issue of the journal Animal Conservation.<br />

the wholesale price of<br />

an adult minke whale<br />

can reach as high as<br />

$100,000<br />

MMI <strong>Newsletter</strong> December 2009 7 OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

<strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> <strong>Institute</strong><br />

Hatfield <strong>Marine</strong> Science Center<br />

2030 SE <strong>Marine</strong> Science Drive<br />

Newport, OR 97365<br />

http://mmi.oregonstate.edu<br />

Record numbers seen<br />

The population of California sea lions along the <strong>Oregon</strong><br />

coast appears higher than normal this year. Biologists say<br />

it happens every few years, and it may be due to El Nino,<br />

the Pacific Ocean warming cycle. The scientists say El Nino<br />

has pushed many of the so-called “forage fish” — such<br />

as herring, squid, hake, sardine and anchovies — north<br />

from California into <strong>Oregon</strong> waters. Jim Rice of <strong>Oregon</strong><br />

<strong>State</strong> <strong>University</strong> says the OSU <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Mammal</strong> Stranding<br />

Network has gotten plenty of calls in the past month about<br />

the sea lions.<br />

But Rice says don’t worry, the sea lions are not stranded<br />

— they’re just following the food, and it’s getting a little<br />

crowded.<br />

Cover photo by Anthony Lombardi<br />

Back cover by Craig Hayslip