Frank Zappa International Festival Guide - Downbeat

Frank Zappa International Festival Guide - Downbeat

Frank Zappa International Festival Guide - Downbeat

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The<br />

News<br />

Views From Around The Music World<br />

Inside<br />

14 / Riffs<br />

/ Third Man Records<br />

16 / Maria<br />

Schneider<br />

17 / Portland Jazz<br />

<strong>Festival</strong><br />

18 / European Scene<br />

19 / Jakob Bro<br />

Sony Masterworks<br />

Resurrects Historic<br />

OKeh Records<br />

Sony Masterworks will soon be offering new wine in a very old bottle.<br />

OKeh Records, one of the most storied labels in record history,<br />

will be rejoining the Sony family of active brands. Nearly a century<br />

after its founding, the imprint that invented the “race” record, organized<br />

the first field recording, produced the world’s first jazz “festival” and laid<br />

the cornerstone of the jazz canon will become Sony’s platform for new and<br />

established artists of varying global backgrounds. Already signed is saxophonist<br />

Craig Handy, and forthcoming projects include recordings from<br />

guitarist Bill Frisell, saxophonist David Sanborn and pianist Bob James,<br />

and John Medeski, whose solo piano album comes out April 9.<br />

In a time of industry shrinkage, why did Sony choose OKeh, a label<br />

Columbia shut down 44 years ago “History is one reason,” said Wulf<br />

Müller, jazz consultant for Sony Classical and overseer of the relaunch.<br />

OKeh has plenty of that; only Columbia and Victor have longer active lifelines.<br />

The label was founded in 1918 by Otto Heinemann, who created the<br />

original OkeH brand from his initials separated by an Indian word meaning<br />

“it is so.” In 1920 Heinemann redesigned the trademark.<br />

In the spring of that same year, OKeh recorded Mamie Smith, a black<br />

vaudeville entertainer. OKeh saw no reason to highlight her race, but to the<br />

black press it was big news. Word spread, and soon the company noticed<br />

sales spikes in black population centers. When Smith returned to record<br />

“Crazy Blues,” that August, black buyers grabbed it up by the thousands.<br />

In an America segregated by race, OKeh had discovered a deep vein of<br />

African-American listeners eager to buy music that few whites even knew<br />

existed. Capitalism took it from there. Others flocked to sign black talent,<br />

while OKeh supplemented its pop line with its 8000 series, the first catalog<br />

specifically targeted to the new African-American market. The black<br />

press called them “race” records. “Race” Recordings Director Richard M.<br />

Jones brought to OKeh many of the leading blues and jazz artists of the<br />

period, including Lonnie Johnson, Chippie Hill, King Oliver and Louis<br />

Armstrong. During the 1920s, OKeh was “the single most important<br />

source of black music,” according to historian and producer Bob Porter.<br />

On Nov. 11, 1926, OKeh was bought by Columbia Records. For the next<br />

several years, it enjoyed a parallel existence with Columbia’s own pop and<br />

14000 race lines, continuing with the Armstrong groups as well as Bix<br />

Beiderbecke, Joe Venuti, Eddie Lang and Bessie Smith in her final session.<br />

The Depression hit Columbia and OKeh hard. OKeh’s output slowed to<br />

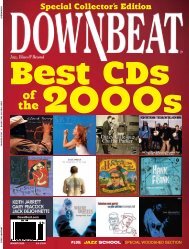

A 1982 Columbia<br />

LP cover saluting<br />

the 1934–42<br />

"Chicago Blues"<br />

period of<br />

its Okeh<br />

heritage<br />

Courtesy of john mcdonough<br />

a trickle. By the end of 1933, Columbia was sold to the American Record<br />

Corporation. The last OKeh recordings of the time came out in 1935, and<br />

for the next five years, the label was dead. Meanwhile, in December 1938,<br />

the Columbia Broadcasting Company bought ARC, promptly restored<br />

Columbia Records as a premium brand, and in 1940 revived OKeh, releasing<br />

records priced at 35 cents with no “race” coding.<br />

But OKeh never recovered from war-time shortages and the two-year,<br />

union-driven recording ban and was retired in 1946. CBS revived it five years<br />

later as a kind of farm club for the company’s premium Columbia brand. In<br />

1953 CBS created Epic, which siphoned off most of OKeh’s pop talent, leaving<br />

it to play in the emerging rhythm & blues field. It continued through the<br />

’60s as an Epic subsidiary and was quietly phased out in 1970. In 1982 Epic<br />

assembled an eight-LP OKeh retrospective emphasizing its blues and r&b<br />

history. When CBS sold off its record business in 1987, Okeh was passed to<br />

Sony Music, which briefly revived the label again in 1995.<br />

The “new” OKeh, now under Sony Masterworks, will be CBS/Sony’s<br />

fourth attempt to make this legendary soufflé rise. “Ultimately there is a rich<br />

tradition of documenting a breadth of creative music forms,” Müller said.<br />

“Therefore, OKeh today can only be an open label for globally created, quality<br />

improvised music.” <br />

—John McDonough<br />

MAY 2013 DOWNBEAT 13