Download - Downbeat

Download - Downbeat

Download - Downbeat

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

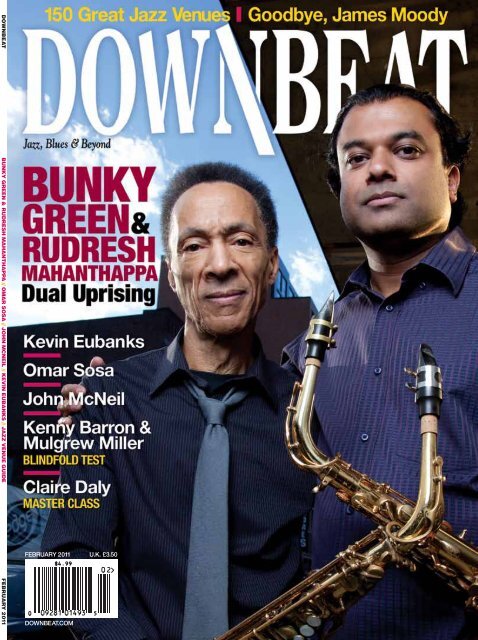

February 2011On the Cover24 Bunky Green& RudreshMahanthappaBreaking FreeOf The SystemBy Ted Panken30Though the feeling they generateis best described as “free,” altosaxophonists Bunky Green andRudresh Mahanthappa both workwithin strongly conceptualizedstructures that leave them plentyof space to soar. A seeminglyodd pairing on the surface, thetwo share a common passionand stimulate each other toextremely high levels of creativity,as heard on their latest CDproject as coleaders, Apex.Omar SosaCover photography by Jimmy KatzMassimo MantovaniFeatures30 Omar SosaGoes DeepBy Dan Ouellette34 John McNeilAll WitBy Jim Macnie38 Kevin EubanksShapes HisPost-Leno CareerBy Kirk Silsbee42 150 Great Jazz VenuesAn International Listingof the Best Placesto See Live Jazz55 Mina Cho 59 Mike Reed 67 Kneebody68 TarbabyDepartments8 First Take10 Chords & Discords13 The BeatRememberingJames Moody17 European Scene18 Caught20 PlayersJohn HébertJames FalzoneAndrew RathbunMilton Suggs51 Reviews70 Master ClassClaire Daly72 Transcription74 Toolshed78 Jazz On Campus82 Blindfold TestKenny Barron &Mulgrew Miller6 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

First Take | By aaron CohenRudresh’s MissionAbout 15 years ago, I went to Chicago’s Green Mill jazz club for adifferent sort of gig. The event was a CD-release party that agroup of master’s degree candidates at Chicago’s ColumbiaCollege’s arts, entertainmentand media management programorganized to celebratea release on their own label,AEMMP Records. While indierecord labels had a betterchance for success—actually,survival—in the mid-’90sthan they do today, this wasstill a quixotic venture comingfrom a group of students.AEMMP was even moreidealistic in that their signingwas a young, and uncompromising,jazz alto saxophonistnamed RudreshMahanthappa.Needless to say, Mahanthappahas come a long waysince the release of his debutdisc, Yatra. But even backthen, his assertive tone andunique way of combiningjazz with South Asian musicrevealed that he had an originalvision and determinationRudreshMahanthappa,circa mid-1990sthat would take him far in any art. He’s also always had a deep respect forthe traditions he chose to investigate, and that includes the work of jazz elderBunky Green, who shares Ted Panken’s cover story with Mahanthappafor this issue.In talking with Mahanthappa this past week about when I met him atthe Green Mill in 1996, he said that the career he’s built for himself was alwaysthe dream, but, of course, it’s never guaranteed. He also is thankfulfor the opportunity that the upstart label gave him. Having a disc in handwas a valuable calling card when he moved to New York the following yearand began encountering the heavier hitters in the media (this was an era beforedownloads, or e-mailed mp3s). All of which reaffirms that the dreamsof a group of Midwestern students should never be taken lightly.The reason why AEMMP signed Mahanthappa, and held its party atthe Green Mill, was because of one particular student, Michael Orlove,who was handling the label’s a&r. Then—and now—Orlove has kept hisear toward finding sounds from around the city and around the planet thatChicagoans need to hear. Orlove is currently senior program director forthe city’s department of cultural affairs. He’s been the driving force forthe city’s stellar world music festival, as well as excellent free events yearroundat the Chicago Cultural Center. The Green Mill and the ChicagoCultural Center are included in this issue’s venue guide: this club and civicinstitution show that it takes a combination of smart entrepreneurs, publicprograms and educational efforts—often, working together—to build alasting audience for such artists as Mahanthappa.This issue also includes a memorial tribute to the wonderful saxophonist/flutistJames Moody, who died on Dec. 9. Along with his beautiful melodicfeel and warm sense of humor, he and his wife, Linda, were tirelessadvocates for jazz education. For information on how to donate to theJames Moody Scholarship Fund, go to his website, jamesmoody.com. DBcredit8 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

Chords & Discords MakingMcLaughlin’s DayI just got home yesterday eveningafter six weeks in the UnitedStates, and the DownBeat ReadersPoll award had arrived yesterdaymorning! Good timing! I justwanted to thank you and thestaff at DownBeat for providingmusicians and music lovers withsuch a great magazine over theyears. I’ve been reading DownBeatsince the mid-’60s and to win anaward from DownBeat has specialsignificance to me. The plaque willoccupy a special place in my home.John McLaughlinMonacoStop Thieves!Thanks very much for the article onInternet piracy of music publications(“Thief!,” January 2011). Iwould like to make it clear thatSher Music Co. is still very muchin the business of selling ourworld-class jazz fake books. Mystatement that “We are out of thefake book business” referred tothe great difficulty in justifying the productionof new fake books when we know they will bescanned and distributed free of charge all overthe Internet. My hope is that people readingyour article will be made aware of the seriousnegative consequences of illegally downloadingbooks and refrain from this unethical practice.Chuck SherSher Music CompanyClean Language, PleaseI must agree with Kevin McIntosh’s letter(“Chords,” January) concerning cursing in yourinterviews. I host a jam session for studentsonce a month, and encourage kids to takecopies of your magazine (which DownBeatvery graciously provides). I often think abouta parent’s reaction if they ever pick up themagazine and read something like that.Surely the language can be edited or bleeped.As a subscriber since 1977, I know you used todo that. What changed? Students get enoughof that kind of “education” in their daily lives.Better to have them focus on the music.Mike EbenReading, Pa.Jamal Deserves HonorIt’s amazing that DownBeat readers almostvoted master pianist/trio trailblazer Ahmad Jamal(#2) into the Hall of Fame themselves, insteadof the DownBeat critics, who, to their embarrassment,have left this undone for decades. Jamalwaits, while Herbie Hancock, Chick Coreaand Keith Jarrett, all employees of Miles Davis,went in ahead of the man who influenced him(and that’s no disrespect to their individual talents).Let’s hope the Veterans Committee won’thave to do it. I wonder just how many of Davis’pianists were told, “Play like Ahmad Jamal.”Ron SeegarEl Paso, TexasErskine Nails ItPeter Erskine’s “Woodshed” (November) is righton the money. I am 75 and have been aroundthe drum scene for 60 years. Not only does hisarticle apply to the ride cymbal, but it can alsobe adapted to brush works and drum solo patterns.I recommend it to young drummers whoare trying to get the clutter out of their playingand play in a way that moves the tune forward.Jim MurphyOrmond Beach, Fla.Correction• The title of Ernie Krivda’s disc in “Best CDsof 2010” (January) was incorrect. It shouldhave been written as November Man(CIMP).DownBeat regrets the error.Have a chord or discord?E-mail us at editor@downbeat.com.John McLaughlin10 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

TheNews & Views From Around The Music WorldInside 15 I Riffs16 I Nicole Mitchell17 I European Scene18 I Caught20 I PlayersMoody’sMood For LifeFriends, colleagues celebrate JamesMoody’s magical personalitySaxophonist/flutist James Moody died on Dec. 9, of pancreatic cancer,at 85 near his home in San Diego, Calif. His career stretchedback across nearly 65 years of jazz history, and while it was a somberend to a life of ebullient music making, his friends and colleagues choseto celebrate his life—not his passing—during the days that followed.“It’s nothing to mourn about,” Sonny Rollins said. “It’s not that I’m notsorry we won’t get a chance to hear him play any more or be in his company.That’s true. But it’s also really a joyful moment because he was here inthis life and look what he left people, a legacy of wonderful music and thememory of a wonderful person. To know him and think about him bringslight to me. We can’t feel sad or sorry. We have to feel good about a manlike Moody.”Moody was born in Savannah, Ga., on March 26, 1925, and raised inNewark, N.J. He converged with Dizzy Gillespie’s first big band in the summerof 1946. His earliest work can be heard on Dizzy Gillespie: ShowtimeAt The Spotlite (Uptown). Gillespie became a mentor to the youthfulMoody, a role that in some ways made brothers of them for life. The earlyband was a hive of musical energy. That’s when saxophonist Jimmy Heathfirst met Moody (he would join the band several months after Moody left),and began a life long friendship. In 2005 Heath described his friend inthe lyric he wrote to “Moody’s Groove” (“Moody has more kisses thanHershey’s…”), which the two performed in the Gillespie All-Star Big band.“He is an original,” Heath said. “No one else in the world is like Moody,one of the greatest human beings I ever met. We called each other ‘Section’because we played in the saxophone section. Everybody remembers howhe outgoing he was, and he was always that way, I think, though the kissinghe might have picked up in Europe.”In the Gillespie band of 1946–’48 Moody helped set the bar for a cominggeneration of young saxophonists who would shortly consolidate thefoundations of modernism. One of them was alto saxophonist Phil Woods.“I loved Moody,” Woods said. “His joy and energy were contagious.And he was one of the best improvisers ever! No one ran the changes likeMoody—nobody! And there was never a more spiritual man than Moody.His horn and, indeed, his very persona exuded warmth and love. He wasthe only man whose kisses I welcomed. When he entered a room he kissedJames Moodyeveryone in it—and did the same when he exited. There was only oneJames Moody. I will miss his music and I will miss his kiss.”The eras of Moody’s career can be sliced in several ways: by decade, bygroup, by association. He converted to Baha’i in the early ’70s, followingGillespie, and some regard that as something of a watershed. But to friendslike Woods, he was a fundamentally spiritual person, before and after hisconversion to Baha’i, with or without the patina of an official faith.“He was one of the most humanistic people I ever knew,” noted ToddBarkin, producer and owner of the Keystone Club in San Francisco, whereJack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotosFEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT 13

Moody played often in the ’70s. “I think that Baha’i just completed the circle,and Dizzy, too. They were naturally predisposed to that view of life. Itjust fit.”Moody came to wide prominence in the early ’50s with a vocalese versionof his 1949 solo on “I’m In The Mood For Love,” revised by KingPleasure as “Moody’s Mood For Love.”“It became a big seller in the black community,” Rollins said. “Whenwe heard it, it wasn’t Charlie Parker or Dizzy, so it didn’t have the impacton us—meaning my younger colleagues who were interested in bebop. ButI’m glad it gave him some prominence and he soon transcended that in hisother work.”Throughout much of the 1960s, he worked with Gillespie and his owngroups, many of which included bassist Bob Cranshaw.“He was the best,” Cranshaw said. “I enjoy Moody because he was seriousabout music but he had fun doing it. He kept you on your toes andkept your laughing. He put a lot into his work, and working with him wasa joy. When I came to New York around 1960, his was one of the first gigsthat I got. I was with Moody around the time he became a Baha’i, and allI can say is that it made him even more loving. He kept a wonderful atmospherearound him.”Moody and Rollins never played together, but their groups played jointgigs during the ’60s in the Jazz Gallery in New York. But Rollins was unusuallycoy in remembering those days. He volunteered an event of someimportance to him, then having brought it up, said, “I’m not going to revealthe incident, but it was between us and it was very educational and informativefor me and helped me grow up. I’ll leave it at that because the detailsare a little too embarrassing to me.” What was the lesson then? “That’swhat I don’t want to be specific about,” Rollins said as he laughed. “Butwe’ve been close friends since then. Maybe when I’m past being active inthe world, I might relate it.”Moody’s career touched successive generations over six decades, mostrecently the brilliant young singer Roberta Gambarini, who first sawMoody in Italy with her parents when she was nine. They met again inCape Town after a performance in 2002.“When I got off the stage and I came down the stairs,” Gambarini said,“his arms were stretched out for a big hug. He loved to hug everybody.”Throughout the last decade, their musical relationship has becomesomething close to a partnership.“He was just one of the most amazing human beings who ever walkedthis Earth,” she said. “He had an endless source of life and joy. There wasBop-era Moodyan aura about him, a special light. He had a gigantic heart as a man and amusician, and also one of the most inquisitive minds that you could find.Until the end he had an incredible interest in younger players. I rememberonce he went up to a wonderful young saxophone player, and he said heloved what he was doing and could he check out how he was doing it. Andthe player said, ‘But Moody, I got it from you.’ He was always on the search.He took the language and stretched it.”As a young person working with a veteran, Gambarini was constantlyaware of how Moody connected her to the history of the music.“One night we were playing at Lincoln Center,” she recalled, “and Iwas standing next to him listening and thinking this is what it must havefelt like to be in those days with the vibration of Charlie Parker and all theother giants. He brought that with him when he played.”—John McDonoughDownBeat ArchivesMoody: A Hard Man Not To LoveIn the fall of 1976 James Moody was in Chicagoto tape a “Soundstage” program forPBS. “Dizzy Gillespie’s Be-bop Reunion”was a big affair. In addition to Moody, therewas Sarah Vaughan, Milt Jackson, KennyClarke, Al Haig, Joe Carroll, some others and,of course, Gillespie. The taping was scheduledfor two consecutive days. But by the end of dayone, a suspicious-looking sore had flared onGillespie’s upper lip. A doctor looked at it andtold Gillespie not to play until a biopsy could bedone. Word spread quickly.That evening I found myself with a dozenor so musicians from the program at a neighborhoodrestaurant. We occupied four or fivebooths and tables, and I was sitting in oneacross from Gillespie, mostly listening. Moodycame over at one point, eager in his concernfor Gillespie’s lip. The conversation went somethinglike this:“Your lip,” asked Moody, “how is it?”“Ahhh, nothing to worry about,” Gillespiesaid.“Look, this may seem a little strange,”Moody said, “but it can’t hurt. OK?”“What?” Gillespie asked.“Just hold still a minute. Be still. Don’tmove.” Moody then leaned into the booth,placed two fingers on Gillespie’s upper lip, andheld them there for 15 or 20 seconds. It seemedlonger. Nobody said a word. A few quietly tradedperplexed glances. Finally Moody lifted hisfinger.“That’s it, “ he said. “That’s all. We’ll see.Right? OK? Say nothing more.” Gillespiesmiled, clutched Moody’s hand for a second,and that was it. “Let’s see what happens,”Moody said returning to an adjoining booth.As one who floats somewhere betweenneutrality and skepticism on matters spiritual, Isee such expressions of “belief” from the perspectiveof an outsider. Yet, I couldn’t help feelinga little moved by the utter ingenuousnessand innocence of Moody’s little deed and thespirit that rooted it. No hint of moral authority;no adulteration of ritual, fanfare, pretense,preaching or even promise. Like he said, “Itcan’t hurt.”The lip sore soon passed. I don’t knowwhether Moody’s healing energy intervened.But the purity and unselfconsciousness of it allstruck me as uniquely heartfelt. It was an opennessMoody seemed to spread compulsively inall directions. I didn’t know him well, but when Iwould see him from time to time over the years,he not only seemed to recognize me. He wouldgreet me with a big bear hug that often left thepungent scent of gardenia cologne clinging tome for the next hour. James Moody remains ahard man not to love. —John McDonough14 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

Riffs Ornette ColemanMoers Return: Ornette Coleman will headlinethe 2011 Moers Festival, which runsJune 10–12. He had previously appeared atthe German event in 1981 with Prime Time.Tickets are available. Details: moers-festival.deAlligator @ 40: Chicago-based blues labelAlligator is celebrating its 40th anniversarywith a slew of historic releases. Companypresident Bruce Iglauer has selected andremastered tracks for the two-disc The AlligatorRecords 40th Anniversary Collection.The label is also releasing vinyl editions ofits back catalog, including Buddy Guy andJunior Wells’ Alone & Acoustic.Details: alligator.comCaine Fellowship: Pianist Uri Cainereceived a $50,000 United States Artistsfellowship grant on Dec. 7.Details: unitedstatesartists.orgBlues Home: Memphis-based Blues Foundationwill begin moving into its first permanenthome in March. The 4,000-square-footlocation at 421 S. Main St. will centralize thefoundation’s educational, audio-visual andretail opportunities, in addition to housingits staff and operations. Details: blues.orgBayou <strong>Download</strong>: The New Orleans Musicians’Clinic has released a digital downloadof Down On The Bayou II Live Jam FromNew Orleans. Participants include IvanNeville, Luther Dickinson and Gov’t Mule. Allproceeds from the sale will benefit the clinic.Details: neworleansmusiciansclinic.orgChicago Matinees: Chicago’s Old TownSchool Of Folk Music has announced a newseries of matinee performances of jazz composersat its 909 W. Armitage Ave. locationon the first Sunday of each month.Details: oldtownschool.orgKelly Meets Woods: Saxophonists GraceKelly and Phil Woods have teamed up fortheir upcoming disc, Man With The Hat(Pazz). Details: gracekellymusic.comFEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT 15

European Scene | By Peter MargasakLithuanian Label Contradicts Nation’s Aesthetic Status QuoFor many years jazz was culturalcontraband in the Soviet Union, soit makes plenty of sense that manyof its underground practitionerswere musical radicals. No groupto emerge from the Soviet era wasbetter or more influential than theGanelin Trio, a product of Lithuania.Yet as jazz lost its subversivestatus, commercial treacle cameflooding in.“Festival organizers startedbringing in more mainstream, fusionand smooth jazz or world jazzgroups to Lithuania,” said DanasMikailionis of the Vilnius-based labelNo Business Records. “Thevast majority of listeners [here]tend to listen to easily acceptableand superficial jazz.”Since forming in 2008, NoBusiness has combated this statusquo, releasing music by Americanand European players, and in thecase of the superb reedist LiudasMockunas, local musicians whoDanas Mikailionisfly in the face of those toothlesssounds. The label’s appearancewas long in coming, emergingfrom Thelonious, a Vilnius recordshop that Valerij Anosov started in1997 and coming on the heels ofan important concert productionconcern that’s brought people likeMatthew Shipp, William Parker,Howard Riley, Barry Guy and JoeMcPhee to the city.“The concerts we organizedbecame a great introduction tothe music industry and they gaveus brilliant musical material thatcould not just be left on the shelf,”said Mikailionis. “But the real inspirationwas Mats Gustafsson.Mats encouraged us to go aheadwith the label, and the first recordingswe released involve his soloand group improvisations withthe best contemporary Lithuanianjazz musicians.”While a sizable chunk of the label’sexpanding catalog, which alnumbersnearly three dozen titles,were made from live recordingsof concerts they had presented inVilnius, No Business branched outwith new studio projects as wellas archival releases from Americanand European players.“Wenever saw the goal of the label injust documenting the jazz activitiestaking place in Lithuania,” he said.In 2010 the imprint came intoits own, offering historic anthologiesfrom groups like Commitment,Jemeel Moondoc’s Muntu andAmalgam, as well as acclaimednew recordings by drummer HarrisEisenstadt, trumpeter Kirk Knuffkeand bassist Joe Morris. This yearlooks even ambitious, with archivalreleases—boxed sets of Parker’sCentering Recordings, Billy Bang’sSurvival Ensemble and solo workof pianist Howard Riley—and newtitles by Tarfala Trio (Gustafsson,Guy and Raymond Strid), ThomasHeberer and John Butcher.Mikailionis said he would lovefor No Business to release morework by Lithuanians, but with theexception of Mockunas he feelsthat most local musicians haven’tappealed to the label’s aesthetic.“Each year during the Vilnius JazzFestival you can listen to youngmusicians from the Music Academythat have some good potential,”he said. “But after they finishtheir education it seems like theirenergy vanishes.” DBFEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT 17

Caught AfroCubismReconnects Cuba,West Africa inNew YorkDespite its Grammy win, record-settingsales and enormous critical praise, 1997’sBuena Vista Social Club was only half the projectit was intended to be.World Circuit’s Nick Gold had initiallyplanned to gather a group of prominent Cubanand African musicians for a recording session,but the Africans were unable to secure their visas,leaving Gold and his producer, Ry Cooder, todo a little improvising of their own by inviting afew more players from Havana to round out therecord. The monster success of the resulting albumwas serendipitous, if accidental.More than a decade later, Gold’s completevision came to fruition with the recording ofAfroCubism, a marriage of music from Cubaand Mali, countries that share similar rhythmictraditions and proclivities for improvisation—notto mention political ties that have caused culturalcross-currents since the beginning of the ColdWar. The group, which features Buena Vista tresguitarist Eliades Ochoa and his band, GrupoPatria, and Malian kora legend Toumani Diabatéperformed the second stop on their NorthAmerican tour at Town Hall on Nov. 9.The highly anticipated show kicked off on asour note when Dan Melnick announced thatvisa problems had left the ngoni player, BassekouKouyate, stuck in Canada. But that road bumpturned out to be the show’s only impenetrablemusical border, as Ochoa and Kasse MadyDiabaté helmed nominal leadership duties thatoften melded their similarly wistful, emotionchargedvocal contributions, despite the languagedifferences.Collaboration and cross-pollination were themain message of the evening, even as Diabatépeeked out from behind his kora to drop the occasionalzinger, at one point teasing that NewYork might not be as rich in culture as it isfinancially.In “Mali Cuba,” solos changed hands swiftlyand succinctly, with balafon player LassanaDiabaté’s agile and chromatic lines balancingout the more soothing kora swells. Grupo Patria’sunison horn section added a sunny layer of salsato even the more traditional, Malian-leaningtunes, not unlike the lineup in Toumani Diabaté’sSymmetric Orchestra.Despite the abundance of marquee namesonstage, guitarist Djelimady Tounkara emergedas an unexpected star of the evening. His bluesdrenchedsolos and playful, rock-infused vampsharkened back to his days with Salif Keita’s RailBand from the ’70s. Near the end of the show,he teased Ochoa and Toumani Diabaté as theymade their way through the Cuban classic,Eliades Ochoa (left), Baba Sissoko and Yuinor Terry (rear)“Guantanamera,” while the audience alternatelysang the chorus and giggled as Tounkara coylychallenged his bandmates with a few mean calland-responseriffs until Ochoa finally surrenderedand led everyone back to the bridge.In fact, the balance of spotlight sharing wasalmost as remarkable as the way the two musicalcultures complemented each other. The hollow,spare sound of the balafon accented the Cubanpolyrhythms in songs like the Cuban hit “LaCulebra,” putting a new spin on a Latin classic.Meanwhile, Tounkara’s rolling, danceable guitarriffs on the more Malian-led “Nima Djala”became a comfortable vehicle for Ochoa’s tressupport.In the end, encores of “Bensema” and “Paralos Pinares Se Va Montoro” roused the audienceto stand up, dance and cheer—as much, itseemed, for the music as for Toumani Diabaté’sdemand that it’s time to “stop stigma and discrimination.”—Jennifer OdellJack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotosDouglas EwartMichael JacksonImpassioned, Playful AACM AnniversaryCelebration Enhances Its MissionChicago’s Association For The Advancementof Creative Musicians held its 45th anniversarycelebration with particularly fascinatingevents at the University of Chicago and the city’sMuseum of Contemporary Art.An event at the university’s Mandel Hall onNov. 11 coincided with AACM trombonist/conceptualistGeorge Lewis’ residency at the institution,where he had taught a graduate seminar“Improvisation as a Way of Life” withphilosophy professor Arnold Davidson. Lewisplayed with German pianist Alexander vonSchlippenbach plus another piano prepared withone of Lewis’ pioneering computerized systemsprogrammed to permit interaction with live performers.After an intense sonic dialogue, duringwhich fragments of Schlippenbach’s playingwere reconstituted and fed back to him bythe futuristic player piano, Lewis, the pianist andDavidson led a discussion about man, machineand the broader social model suggested by the artof improvised music. The night concluded with arousing set from the 27-member AACM GreatBlack Music Ensemble.Douglas Ewart’s set at the museum on Nov.19 with his 11-piece “Inventions” was contoured18 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

James FalzoneSubtle InfusionsClarinetist and composer James Falzonecontemplated moving to New York aftergraduate school at Boston’s New EnglandConservatory, or perhaps Europe, as he felt astrong affinity with the European creative musicscene. But he opted to return to the Chicago areahe had left behind.He describes that decision as one of the mostfruitful of his life. Since the improvised and experimentalmusic community in Chicago hadgrown so exponentially in the last 10 years, it wasthe perfect place for him to be.Falzone feasted in the academic environmentof NEC, taking courses in Medieval music,Indian ragas and Turkish traditions, klezmerwith Hankus Netsky’s ensemble, even a classzoning in on Billie Holiday. He now teaches aninterdisciplinary seminar at Chicago’s ColumbiaCollege that has as much to do with the visualarts and literature as music.From the outset his music has been self-produced,most recently on what he dubs his AllosDocuments label. Lamentations (2010) featureshis Allos Musica trio (allos is the Greek word for“other”) comprising oud player Ronnie Malleyand percussionist Tim Mulvenna. The group digsdeep into Arabic modes. One is a Muwashah (acourtly lovesong from Andalusia), another writtenby oud player Issa Boulos, but the rest of the18 tracks are conceived by Falzone himself aslaments, “a musical/poetic genre that has transcendedcultures and time,” as he puts it.When Falzone was in Boston seeking out themusic of Egyptian singer Oum Kalsoum, whomhe likens to Holiday, 9/11 struck. Since he hadsuch respect and awe for the culture Americaseemed to be retreating from, Lamentations is inpart his reaction of frustration and sorrow to theethnic slants of the conflict.A gentle soul, Falzone is something of a hippieby his own admission, who home-birthedand home-schools his kids and bakes his ownbread. His 2009 release Tea Music with the quartetKlang (vibraphonist Jason Adasiewicz, bassistJason Roebke, drummer Tim Daisy) makesreferences to varieties of the benign beverage hewould sip while composing (he gave up coffeefor a while due to migraine headaches). Song titleslike “No Milk,” “G.F.O.P” (Golden FloweryOrange Pekoe) and “China Black” have scantrelevance to the superb Jimmy Giuffre-inspiredmusic on the CD but bespeak Falzone’s gourmetpalate and hypersensitivity to the clarinet’s timbraland tonal niceties, for which he developed anear, aged 11, when his clarinetist uncle gave himThe Jimmy Giuffre Clarinet LP.Such nuance was evident in a spontaneousmeeting with Austrian electronics musicianChristof Kurzmann at Chicago’s Cultural Centerlast November. Thrown together with Kurzmannby curators of the Umbrella Festival, Falzonewas forced to negotiate terms with a laptop musicianfor the first time. “You have two experiencedmusicians in a slightly awkward moment. It presentsa wonderful balance between being yourselfand being a receptacle,” said Falzone. BothFalzone and Kurzmann generated a sweat duringtheir duo and Falzone drew on a host of resources,including microtones, altissimo shrieks,didgeroo-like growls, as well as judicious use oflow volume and space.Not central to the vein of heavier-blowinghorns that followed Ken Vandermark on theChicago scene, Falzone is nonetheless a virtuosoand a brilliant strategist whose concepts canbe through-composed. Though he wouldn’t acceptthe term as a branding model, he identifieshimself as a “third stream” exponent (toborrow Gunther Schuller’s jazz/classical bridgingterm) and has found musicians, such as cellistFred Lonberg-Holm, who can match his vision.Lonberg-Holm and Falzone are featuredon Aerial Age with Daisy’s group Vox Arcana,the first release on Allos Documents not underFalzone’s name. The chamber-like osmosis is astonishinglygood, only possible given the subtlevibrations and proximity of empathetic, versatiletalent (the next record from Klang, incidentally,will include tunes associated with BennyGoodman—continuing Falzone’s fascinationwith the blend between vibraphone and clarinet).It’s like sharing the environment endemic to oneof Falzone’s esoteric teas: “There’s this JasmineOolong tea from Taiwan where the tea leaves drymerely in the presence of the jasmine, absorbingits aroma.” —Michael JacksonMICHAEL JACKSONFEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT 21

Players AndrewRathbunSolitary ManSaxophonist Andrew Rathbunhas recorded 10 albums of eloquent,provocative and challengingmusic, each with a unique angle.He catalogued the failuresof George W. Bush on AffairsOf State, paralleled sculpture tojazz with Kenny Wheeler forSculptures; improvised on Ravel,Mompou and Shostakovich (withGeorge Colligan) on Renderings;and paired the poetry of MargaretAtwood with jazz on True Stories. Rathbun is interested in finding new solutionsto old questions, and challenging standard forms. His latest, The IdeaOf North (SteepleChase), follows a thread left by troubled Canadian pianistGlenn Gould.“Glenn Gould’s [1967] CBC radio documentary [also titled The Idea ofNorth] explored the netherworlds of Canada,” Rathbun explains. “He said,‘Let’s get out of the urban centers and really see what’s north of the permafrost.’Some of it was just the sound of his boots crunching in the snow forsix minutes. He approached these radio plays as if it were Bach, with vocalcounterpoint. He’d interview someone about ice fishing, then another guyabout what it’s like to start your car at 40 below. He edited the two interviewstogether so they played simultaneously, like counterpoint. It was performanceart. Gould was a nut-job, but it’s an interesting way to approachspoken word.”By extension, Rathbun, also a native Canadian, depicts the farther regionsof his homeland as a cold, desolate, isolated place, which mirrors, hebelieves, the life of the average jazz musician. The CD’s liner notes ask,“What effect does solitude have on a person? What can it offer someone?How can one grow as a result of being alone?”“That’s the existence of the musician,” Rathbun says. “You spend somuch time working out your music. It’s often a solitary life. Writing themusic takes a long time, you’re alone, until you join with other musiciansto perform it. I was thinking, ‘What can all this solitude offer someone?’Basically trying to channel that into the compositions—the idea of the artas a solitary pursuit, and then the vastness of the country and how many ofits residents also live a solitary existence.”The Idea Of North, performed by Rathbun, Taylor Haskins (trumpet),Nate Radley (guitar), Frank Carlberg (piano), Jay Anderson (bass) andMichael Sarin (drums), embraces the enormity of the Canadian Territoriesand the netherworlds of the musical mind in the titles “Across TheCountry,” “Harsh,” “Arctic,” “Rockies” and “December.” Wayne Shorterand Christoph Gluck material is also explored. Rathbun’s compositionsare alternately mysterious, cerebral and free, performed with tight executionand extreme improvisation. The group plays like a whipsaw cuttingthrough the frigid Canadian permafrost.“Sometimes I write music with a narrative in mind,” Rathbun says, indescribing his sound(s). “It’s almost like scoring a movie that doesn’t exist.The music that usually gets attention is either totally out, or the more insidetonally structured stuff. I think of myself as being in the middle. I loveto play free; I do it all the time. But I also love structure and harmony andchord changes and standards. But I bring a different turn to that music. Theguys in the middle are the guys who get ignored. But to me, the guys in themiddle are making the most music. That is who I gravitate to and seek out.”—Ken Micallef22 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

MiltonSuggsCircuitousTrajectoryMilton Suggs once set hissights on being a jazzpianist; instead he becamea commanding jazz singer.As evidenced by his debutCD as a leader, Things ToCome (Skiptone Music), the27-year-old Chicago-basedvocalist made a wise decision.The disc highlights a singersteeped firmly in the traditionof crooners such as JoeWilliams, Eddie Jefferson andJon Hendricks but with modernsensibilities that put him in the company of contemporaries like JoseJames and Sachal Vasandani.Suggs powers his mellifluous baritone through vocalese treatments ofCedar Walton’s “Ugestu” (recast as “Fantasy For You”) and TheloniousMonk’s “Round Midnight,” catchy originals like the forceful “My LastGoodbye” and the ballad “Seize The Moment,” and glowing renditions of“We Shall Overcome” and “Lift Every Voice And Sing.” He sings in aneasy, conversational manner that’s pliable enough to entice the jazz puristand melodically economical enough to pique the curiosity of r&b fans.Suggs’ trajectory to becoming a vocalist was rather circuitous. The sonof jazz bassist Milton Suggs—who played with Mary Lou Williams, ElvinJones and Rahsaan Roland Kirk—Suggs was born in Chicago but grew upwith his mother in Atlanta. His initial career choice was broadcast journalism,which he studied at Florida A&M University. “I liked the idea of usingthat broadcaster’s tone—using my voice in that type of way,” Suggs explained.“But it started not to feel right after a couple of months.”Having studied bass and other instruments as a grade-schooler, Suggstook a renewed interest in music during his freshman year of college. “I decidedto try to take some piano classes,” he recalled. “I was going to try toenroll in the music program at Florida A&M, however I didn’t have enoughplaying experience.” So his mother encouraged him to visit Chicago andtake lessons from his godfather—veteran pianist Willie Pickens.Suggs journeyed to the Windy City for what at first was just going to bea summer of learning piano with Pickens. He enjoyed his studies and theChicago jazz scene so much, he decided to stay. “[Pickens’] first mode ofattack is to focus on the blues,” Suggs said. “He always said that if you canplay the blues and ‘Rhythm’ changes, then that would be your foundation.”Pickens also imparted the values of listening intently and exploring differentapproaches to standards. “We would sit down and go slowly duringpractice and figure out what we were hearing. There was a lot of repetition.I would do four measures of a song about 20 times over and try to exploredifferent options just to figure out what I’m hearing.”Suggs enrolled at Columbia College Chicago and began to hone hisskills as a pianist and vocalist. He went on to get a master’s degree in jazzstudies from DePaul University, where he received a DownBeat StudentMusic Award for outstanding vocal performance. When Wynton Marsalisheard Suggs sing with the DePaul University Jazz Ensemble in 2008, thetrumpeter encouraged him to focus on vocals.When asked if he’ll ever reignite his interest in jazz piano, Suggs said,“I feel like I have more of a voice as a singer than as a pianist. I felt like Ididn’t have anything really to say as a pianist.” —John MurphFEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT 23

Bunky Green & Rudresh MahanthappaProdded by Jason Moran on piano, FrancoisMoutin on bass and either Jack DeJohnetteor Damion Reid on drums, the two alto saxophonistsblow like duelling brothers, each projectinga double-reed quality in their tones,Mahanthappa’s slightly darker and tenoristic,Green’s more nasal and oboeish. Both workwith complex note-groupings, flying over barlineswhile always landing on the one. Thoughthe feeling is “free,” both work within stronglyconceptualized structures that provide space tosoar within the form and are thoroughly groundedin “inside” playing and the art of tension-andrelease.“It’s surprising what they come up with,”DeJohnette summed up. “They stimulated eachother to the higher levels of creativity.”Two days into a four-night CD-release run atthe Jazz Standard in October, Green andMahanthappa convened at Green’s hotel. Greenrecalled their first meeting, in 1991 or 1992,when Mahanthappa—then a Berklee undergraduatewho was loaned a copy of Green’s 1979 recordingPlaces We’ve Never Been by his saxteacher, Joe Viola—presented the elder saxmanwith a tape. “Sounds beautiful,” Green told him.“There’s only a few of us out here trying to thinklike this.”At the time, a short list of those “few” includedM-Base movers and shakers Steve Colemanand Greg Osby, who had discovered Green independentlyas ’70s teenagers, and subsequentlybonded in New York over their shared enthusiasmfor his approach, poring over Coleman’s extensivecassette archive of location performances.Many years before, in Chicago, where Greensettled in 1960, Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarmanand Henry Threadgill, then young aspirants, hadalso paid close attention.“The level of expertise [Green] displayed inhis musicianship and expression were very clearfrom the moment I heard him,” said Threadgill,after witnessing the group’s final night at theStandard. He recalled a concert, perhaps in 1962,in which Green played pieces “structured in theway of free-jazz, the so-called avant-garde category.”He continued: “Bunky was formidable, noone to fool with. I can’t think of another alto playerat a comparable level in Chicago at the time.”DeJohnette cited the “urgency, commandingpresence and confidence” of Green’s early ’60splaying. “Everybody would talk about Bunky,”he said, noting that Green had once brushed offhis request to sit in during a gig at a South Sideclub. “He was legendary even then.”For Osby, Green was less a stylistic influencethan “a guru-type figure who assured me I’m onthe right track, gave me the Good HousekeepingSeal of Approval that what I was doing was theright thing, not to let detractors sway me frommy mission, that I was put here to establish newgoals and force new paths.” Ten years later,Mahanthappa drew a similar message.“I was around lots of tenor players whosounded like [John] Coltrane and [Michael]Brecker, and alto players wanting to soundlike Kenny Garrett,” Mahanthappa recalled.“Bunky’s voice didn’t sound like anyone else. Ineeded that affirmation that it was OK to be anindividual. I heard things—interesting intervallicapproaches—that maybe I couldn’t play yet,but was thinking about. But I also heard the traditionin the music.”Mahanthappa placed his hand at a 90-degreeangle. “This is Charlie Parker,” he said, thenmoved his hand to 105 degrees and continued,“and this is me. It’s all the same material, just rearrangeda little bit—a different perspective. Iheard Bunky doing that at the highest level.”At the time, Mahanthappa, spurred by a tripto India (with a Berklee student ensemble) to beginexploring ways to express identity in music,was absorbing an album by Kadri Golpalnath, analto saxophonist from Southern India who, likeGreen, had systematically worked out inflections,fingerings and embouchure techniques toelicit the idiomatic particulars of Carnatic classicalmusic. As important, he took conceptual cuesfrom such Coleman recordings as Dao Of MadPhat, Seasons Of Renewal and Strata Institute.“Steve extrapolated African rhythm as I aspiredto do with Indian rhythm and melody, not playingWest African music, but doing somethingnew with well-established, ancient material froma different culture,” he said. “It was an amazingtemplate. Steve doesn’t need a kora player or aGhanaian drum line to play with him, and I don’tneed a tabla or mridangam in my quartet. We’replaying modern American improvised music.”In 1996, three years into a four-year stay inChicago, Mahanthappa invited Green toguest with his quartet for a weekend at the GreenMill. Green declined. “It was more about tryingto do something special than about the music,”Mahanthappa reflected. According to altoistJeff Newell, a rehearsal partner who had studiedformally with Green, Mahanthappa “had developeda lot of the things he’s doing now,” projectingthem with a “bright, shave-your-head sound,”as though, a local peer-grouper quipped, “somebodythrew lighter fluid on Bunky.”An opportunity for collaboration arose 13years later, when the producers of Madein Chicago: World Class Jazz approachedMahanthappa—now leading several ensemblesdevoted to the application of Western harmonyto South Indian melodies and beat cycles, eachwith highly structured, meticulously unfoldingrepertoire specific to its musical personalities—to present a concert at Millennium Park. In additionto his blistering sax and rhythm quartet withpianist Vijay Iyer, to whom Coleman had introducedhim in 1996 (he reciprocally sidemannedfor years in Iyer’s own quartet, and they continueto co-lead the duo Raw Materials), Mahanthappahad recently conceptualized Indo-Pak Coalition,a trio of alto, tabla (Dan Weiss) and guitar (RezAbbasi) documented on Apti (Pi); and a pluggedin,ragacentric quintet called Samdhi, with electricguitar (David Gilmore), electric bass (RichBrown), drums (Damion Reid) and mridangam(Anand Ananthakrishnan). Then, too, he was involvedin a pair of two-alto projects: the quintetDual Identity, which he co-leads with SteveLehman, a fellow Colemanite (The General[Clean Feed]); and the Dakshima Ensemble, acollaboration with Golparnath in which Abassi,bassist Carlo DeRosa and drummer RoyalHartigan meld with Golparnath’s sax-violin-mridangamtrio to perform their hybrid refractionsof Carnatic music, documented on the widelypublicized CD Kinsmen (Pi).“They wanted to present Dakshima and addsome Chicago musicians, which sounded likea disaster and was budgetarily impossible,”“I do a lot of analyzing.Maybe I play a phrase,and some experiencecomes up from my life.Or perhaps I see somebeauty in it and decideto keep developingit, and it leads into asong, or pathways Ican utilize on whateverI’m working on.To me, a tune can’t bejust pretty. It has to besomething that fits intothe way I feel about life,so I can express it.” —Bunky GreenMahanthappa said. “But they thought Bunkywas a great idea. Bunky made it clear that hedidn’t want to play 7s and 11s and 13s—it wasmore about trying to find a comfortable placethat would highlight what we both do. It was interestingto compose a blues [‘Summit’] and a‘Rhythm’ changes tune [‘Who’] that sounds likethe same compositional voice I’ve done over thelast decade. I’m trying to learn how to relinquishcontrol of the situation and just say, ‘Whateverhappens, happens.’”Two of Green’s new tunes, “Eastern Echoes”and “Journey,” reflect his abiding interest inNorth African scales and tonalities, and another,“Rainier And Theresia” (dedicated to the late wifeof Jazz Baltica impresario Rainer Haarmann), isthe latest addition to a consequential lexicon ofsearing ballad features. “I didn’t want to get involvedin anything with a lot of changes,” Greensaid. “I don’t feel that music too much now. Our26 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

things kind of hover on the edge. There’s all kindsof room in what we write, and we both like thatyou can take it where you want to.“Like Rudresh, I do a lot of analyzing.Maybe I play a phrase, and some experiencecomes up from my life. Or perhaps I see somebeauty in it and decide to keep developing it, andit leads into a song, or pathways I can utilize onwhatever I’m working on. To me, a tune can’t bejust pretty. It has to be something that fits intothe way I feel about life, so I can express it. Theblues, too. It’s not just a word, it’s a feeling. It’ssomething that you have, and right away, if youplay the right notes, the feeling will be there. It’sbending notes. It’s moaning. How are you goingto play about pain unless you’ve experiencedpain? And how are you going to package it likeCharlie Parker, who just cried over his horn?Those aren’t notes. It’s a man’s life.”Green discovered Bird in his early teens,which coincided with the release of the alto legend’sstudio sides for Dial and Savoy. Green gotthem all. By the time he was 17, he said, “I couldplay everything Bird recorded in terms of imitating.I didn’t know what the hell I was playing. Iwas just stretching, trying to find the notes.”Around this time, Green contracted viralpneumonia. “A doctor came to the house, and Ioverheard him telling my mother that he didn’tthink I’d make it,” he recalled. “I decided that if Idid live through it, all my friends would be aheadof me, so I should practice just in case—I couldhear the ones in my head, so I didn’t need my instrument.I took the hardest songs I could thinkof—‘Cherokee,’ ‘All The Things You Are,’ ‘JustOne Of Those Things’—and transposed themmentally through all 12 keys. The people mymother worked for brought in a famous doctor,who gave me new drugs, which knocked it out,but not until I experienced the white light at theend of the tunnel, the light closing, then fightingfor air to come back, the light opening up again.When I was able to get back to my instrument, Iwas able to play everything I’d practiced.”While attending Milwaukee TeachersCollege, Green worked locally with pianistsWillie Pickens and Billy Wallace, walking thebar on rhythm-and-blues jobs, soaking up GeneAmmons’ spare, vocalistic approach to balladslike “These Foolish Things” and Lester Young’spoetic treatment of “I’m Confessin’.” He hadNew York on his radar, and first visited in 1957,staying at the Harlem Y across the street fromSmalls Paradise, where Lou Donaldson helda steady gig. He sat in with Max Roach’s quintetwith Sonny Rollins and Kenny Dorham onthe say-so of Wallace, then Roach’s band pianist.“I was always able to play fast, especially atthat time, so I was able to hang in and do it,” hesaid. That fall, Donaldson recommended him toCharles Mingus.The audition produced a second transformativemoment, after Mingus told him, “The firsttune we’ll play is ‘Pithecanthropus Erectus.’”Green continued: “I sat there, ‘Hmm, pithecan... ’ ‘You know what that means, man?’ That’sthe way Mingus talked. ‘No, I really don’t know.’‘That means the first man to stand erect.’ He said,‘Play this,’ and played something like bink-dinkdom-deeenngg.I said, ‘Have you got that writtendown so I can see it?’ Then he went off on me—if he wrote it down, I’d never play it right. I said,‘Then play it again.’ I was able to hear it and playit back, and he smiled, and moved on.“Mingus validated how I was starting to feelabout the music—that there must be a systematicway to break free of the major-and-minor system.He’d have you do things like take the neck offyour horn and blow into the bottom part to get avery low timbre on ‘Foggy Day’ because he wantedyou to sound like a ship out in the harbor.”Mingus brought Green cross-country to SanFrancisco’s Black Hawk. On the return trip, hedropped him off in Chicago so that he could attendto family matters in Milwaukee, with theexpectation that Green would soon return toNew York for more club dates and a recording.But Green stayed home, imbued with notions ofthe freedom principle, with the late ’50s innovationsof Coltrane as his lodestar. Green continuedthese explorations in Chicago, where—unable“to afford New York at the time”—he moved inFEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT 27

Bunky Green & Rudresh Mahanthappa1960. He quickly made his presence felt on a scene that he describes as“very fast, but more laid back than New York, so you could do yourself ina less frantic environment.” He cut a straightahead sextet date for Exoduswith Jimmy Heath, Donald Byrd, Wynton Kelly, Larry Ridley and JimmyCobb, and a quartet side for Vee-Jay with Wallace, bassist Donald Garrettand drummer Bill Erskine. He frequently partnered with Garrett on “out ofthe box” projects, including an exploratory trio that did a concert—the oneThreadgill attended—on which they “just started playing and tried to interact—thatwas the whole gig.”A third transformative moment occurred in 1964, when Green, inMorocco on a State Department tour, traveled “through the back woods” tohear a performance. “We saw three musicians sitting on the floor in a circle,”he recalled. “One guy had a bagpipe, another had a small violin, andthe third played a small drum that he put his hand into and played on top.I became mesmerized by the bagpipe player’s skill. It blew my mind, becausehe put together what I was hearing in my head. No chords. There wasa drone of a fifth, and you played around that fifth and resolved it withinyourself. Later, I started studying it and building from it, pretty much theway Rudresh visited his culture and started drawing on it. I’m not trying tocopy the sound. I’m trying to get into the essence of their phrasing and howthey circle the open fourth and fifth tonal centers that they use. I had to giveup the standard jazz lines in order to do that.”Ten years later, Steve Coleman, then 18, heard Green—at thispoint heading a newly formed Jazz Studies department at ChicagoState University—either at Ratso’s on the North Side or CadillacBob’s, around the corner from his South Side house. “Bunky workedout patterns that sounded calculated, like a deliberate effort to get tohis own thing,” Coleman stated. “As a result, his playing is very clear,precise, direct, and I could dig into it, try to analyze it and find outwhat it was. I wanted him to show me what he was doing, so I askedfor a lesson, but Bunky turned me down. He told me, ‘I only give lessonsto cats who need lessons, and you don’t. You need to go to NewYork.’ So I decided I’d listen and grab what I could.“Although I noticed the patterns early on, Bunky used certain devicesthat intrigued me. He developed a special fingering to get a hiccupquality that you hear in North African singers. He also picked upa lot of augmented second intervals, as well as quartal stuff and pentatonics,from that part of the world. Whereas in those countries, thepitches stay pretty much the same, Bunky moved the intervals aroundin different ways. To me the blues is basically a modal music, withouta lot of progression. Bird managed to put sophisticated progressions inthe blues that gave it motion, but let it sound like blues, as opposed to,say, Lennie Tristano or Dizzy. Coltrane figured out a way to move themusic that influenced him from Africa and India. Bunky figured outhow to do this with the North African-Middle Eastern vibe.”Along with what he does on Apex, Mahanthappa’s recent sideman workin DeJohnette’s new group with David Fiuczynski, George Colliganand Jerome Harris and in Danilo Pérez’s 21st Century Dizzy project (thereare several open-ended Pérez–Mahanthappa duos on 2010’s Providencia[Mack Avenue]) may go some ways towards countering a critique that hismusical production—particularly the 2006 release Codebook (Pi), comprisingoriginal pieces constructed of intervals drawn from Fibonacciequations, and Mother Tongue (Pi), on which the compositions draw frommelodic transcriptions of Indian-Americans responding, in their native dialect,to the question “Do you speak Indian?”—is overly intellectual and insufficientlysoulful.“Everyone I look up to is simultaneously right brain and left brain, touse a dated term, or simultaneously intellectual and seat-of-the-pants instinctive,”Mahanthappa said. “Bartok played with Fibonacci equations.Bach played with Golden Section. Even Dufay’s motets, if you pick themapart, have a somewhat mathematical, formal approach. ‘Giant Steps’ and28 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

Omar SosaGoesDeepBy Dan OuelletteWhen he was commissioned by the Barcelona Jazz Festivalin 2009 to be one of three artists to commemorate the50th anniversary of Miles Davis’ Kind Of Blue, Omar Sosatold a Barcelona reporter that what he was being asked todo was like being thrown into a lion-packed arena at a Romancircus. But the Cuba-born, Barcelona-based pianist/keyboardist/bandleader,who has recorded more than 20 albums and garnered three Grammy nominations,did his homework, studied the original compositions closely, assembled a sextetfeaturing guest trumpeter Jerry González to decipher his complex arrangementsand held court at L’Auditori for his festival performance. Sosa, a risk-taker with anadventurous streak and a no-borders attitude, plugged in and presented an electronicallyhued version of Kind Of Blue that was more like the 1969 Davis blitzinginto Bitches Brew than his mellow modal jazz of 1959.FEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT 31

Omar SosaDonning a white robe and a white cap, Sosaopened by fleetingly alluding to “So What,” butfor the rest of the evening avoided playing too closeto the recognizable phrases and melodies of theclassic. He coaxed drummer Dafnis Prieto to playbombastic drums in pockets, conducted waves ofexclamatory horns inspirited by Peter Apfelbaumon sax, soothed González to play a sublime mutedsolo on a gorgeous ballad, then bubbled the proceedingswith mysterious stretches that frothedinto funk, balladic measures that jumped intorhythmic leaps, and strident piano and electronickeyboard lines setting up dense-to-stark passagesthat were both boisterous and beautiful. Eachpiece became a journey of tempo shifts, rhythmicvivacity, exhilarating conversations and pensivebreaks of silence.For 90 minutes, Sosa led the charge throughhis image of Kind Of Blue, which was explosivelyimaginative in some people’s eyes but for otherswas an audacious affront to Davis’ art. Heincluded a spoken word sample of Davis talkingfrom the stage at his last concert in Parisbefore he died. Certainly, Sosa’s interpretationwas markedly different from the straight-uptake of original Kind Of Blue session drummerJimmy Cobb’s variations on the album songbooktwo nights earlier and Spanish pianist ChanoDomínguez’s flamenco-styled rendering of thealbum three nights later.The next day sitting in his apartment (“myhome, my temple”) in the labyrinthine old sectionof Barcelona, filled with small altars to the godsfrom his Cuban heritage, Sosa good-naturedlyscoffed at the critics, one of whom lambasted theshow in a local newspaper. “I knew that some peoplewere going to be negative and complain that Iwrite complex on purpose,” he said. “I knew I wasgoing to be a target because so many people havetheir own perception of the album. But I say thatsomeone can try to dance like Michael Jacksonand may get his steps but never be able to trulydance like Michael Jackson. That’s impossible. Inthe same way, I didn’t want to play like Miles. I respecthim, Bill Evans, John Coltrane, CannonballAdderley, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb toomuch to do that. I never play standards, anyway,but I wanted to research and interpret these songsin my own way. You never play like the masters;you have your own voice.”Sosa read books on Davis’ life and listenedclosely to the solos, the tempos, the conversationsthat were taking place on the album. He thencombined rearranged solos and reharmonizedmelodies in a post-modern pastiche of suspendedharmonies, rushing syncopation and snippets oflines from one song stitched into another. “WhatI did was a more cubist, angular style of arranging,”he said. “All the album solos and melodiesare in my interpretation. I just mixed them all together.If some people aren’t willing to listen forit, that’s not my problem. It’s the way I hear harmony.And then I put in elements of Miles’ laterstyle. I was born in 1965, so I can relate to thatperiod when he was experimenting with differenttempos and colors.”One point that Sosa found particularly offensivewas when the reviewer wrote that Kind OfBlue has nothing to do with Africa. Sosa commentedthat before he wrote one note, he wastotally immersed in his understanding of howDavis possessed the spirit of Africa. “All ofmy music—every single note—is based on theAfrican tradition, but some critics don’t understandwhat the spirit of Africa means,” he says. “Iplayed a chamber music concert in Spain with myAfreecanos Quartet and a symphony orchestra.Some people complained that the evening wastoo refined and didn’t go into the deepest spiritof Africa. What? It was as if the spirit of Africahas to be dirty, or a black guy sweating and beingwild. It can’t be refined and sophisticated?”That notion of delving into the depth of hisAfrican heritage is at the heart of Sosa’sAfro-Cuban-infused music. It’s coursing in hisblood and intertwined in his DNA. While he firststudied marimba and percussion in the conservatoryin his hometown of Camaguey, he switchedto piano while in formal studies in 1983 at theEscuela Nacional de Musica in Havana in pursuitof the musical motherland he was drawn to. Whileclassically trained, he had jazz albums aroundthe house when he was growing up (includingthe album Pianoforte by Chucho Valdés) and listenedas a student to a jazz radio program hostedby the father of drummer Horatio “El Negro”Hernandez. It was during this time that he was introducedto the recordings of Thelonious Monk,who became a major influence.After school, Sosa began his worldwide odyssey,moving to Quito, Ecuador, in 1993, wherehe discovered the African-rooted folkloric musicof Esmeraldas and formed a fusion group.Then he settled in San Francisco in December1995, landing there unexpectedly. While livingin Ecuador on a Cuban passport, Sosa set off toMallorca, Spain, to do some summer gigs. Whenhe prepared to go home, he lost his visa so he wasstranded there and living illegally. Previously hehad applied for an American tourist visa, whichwas approved. “I used it one day before it expired,”Sosa said. “I got on a plane and landed inSan Francisco, where I knew no one and couldn’tspeak a word of English.”A friend of his ex-wife picked him up at theairport, and they both bounced from friends offriends’ apartments. “In one month, I lived insomething like 12 houses,” Sosa said. “I criedlike a baby. I had no friends, no job and no money.Welcome to America.”Sosa had recorded jingles in Ecuador, withthe paychecks being delivered to him in the BayArea, which gave him three months’ worth ofliving expenses. In February 1996, he answereda classified ad looking for musicians to be a partof a Latin combo. He joined the band and beganplaying Spanish, flamenco, cumbia and salsa.He showed up on albums recorded in 1996by Pancho Quinto (En El Solar La Cueva DelHumo) and Carlos “Patato” Valdes (Ritmo YCandela: African Crossroads), and gradually“All of my music—every single note—isbased on the Africantradition, but some criticsdon’t understandwhat the spirit of Africameans. It’s as if thespirit of Africa has tobe dirty, or a blackguy sweating andbeing wild. What? Itcan’t be refined orsophisticated?”became acquainted with several stars on the localscene, including percussionist John Santos,who with his band Machete Ensemble was exploringthe history of Cuban music.“Meeting John moved me to another level,”Sosa said, “He helped me to express myselfbased on what I feel. Everything took a new directionfor me. He told me to stay on my ownroad even if it’s going to be a really long walk.John knew more about my tradition than mostpeople in Cuba. I learned how to hear my ownmusic as well as my tradition.”Santos recalls first meeting Sosa when hesubbed in a band that the conguero often performedwith at the Elbo Room in San Francisco.“We were connecting all night,” he says. “It’s asif we were thinking the same things at the sametime. Omar spoke no English, and my Spanish isOK but it’s not my first language. But what wascool was that we both knew Afro-Cuban folkloricmusic, which I had been exploring my entirelife. We started playing together more and weknew the same musical language. In Omar’s melodyline I could hear the Cuban music, so I wouldrespond with my congas. That would set him off,so he would respond with another melody thatwould get me driving. Omar made me play stuffthat I never thought of playing.”They first played a duo concert together in1997 at KCSM radio’s Jazz on the Hill festivalat the College of San Mateo and later performedconcerts throughout clubs in the Bay Area, includingLa Peña Cultural Center in Berkeley,where they recorded the album Nfumbe, releasedin 1998.Another key person to Sosa’s growth wassaxophonist Peter Apfelbaum, at the time one ofthe most important jazz artists in the Bay Area.In one of the first shows he attended when he arrivedin San Francisco, Sosa went to a small clubon Market Street, The Upper Room, and caughtApfelbaum playing with his band. “Peter instant-32 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

ly became one of my heroes,” said Sosa. “I sawhim play the keyboards, then jump onto the sax,then jump over to the drums. He started singingand doing spoken word. I didn’t know who hewas, but I thought, this is the music that I wantto do. It was multikulti with a lot of tradition, andit was crazy.”The pair officially met a few years later whenSosa was playing a gig at the Great AmericanMusic Hall with drummer Josh Jones, a veteranof Apfelbaum’s big band, HierogylphicsEnsemble. “Omar and I felt a common bond,”says Apfelbaum, now based in New York. “I startedout when I was young drumming and listeningto a lot of African music, so rhythm became abig part of what I do. It’s the same with Omar. Heapproaches his music with a rhythmic foundation,and when I play with him, he always encouragesme to improvise on my saxophone over the Afro-Cuban rhythmic foundation he lays.”As Apfelbaum got to know Sosa better andparticipated on many of his projects, he becameimpressed with how many trails the pianist wasblazing. “Omar is one of those idea guys,” hesays. “He’s prolific, which I admire. Some peoplework hard, but never really change what theyplay. But Omar is constantly changing becausehe has so many ideas of what he wants to do.”Another key Bay Area contact was ScottPrice, a former newspaper publisher who overseesSosa’s career to this day. He created OtáRecords exclusively for the pianist to pursuehis multifarious projects (the label is part of theHarmonia Mundi distributing network) and tohelp manage his career, even to the point of occasionallyworking as a road manager on the pianist’s150-dates-a-year tours, which includeda gig at the Highline Ballroom in New York inOctober 2009. “I wanted to give Omar the opportunityto record widely and frequently,” Pricesaid over coffee at Union Square’s Joe’s Art ofCoffee cafe. In fact, since his first album, OmarOmar, Sosa has recorded a whopping total of 23albums, including his upcoming solo piano album,Calma (to be released March 8) and themuch-heralded Across The Divide: A Tale OfRhythm & Ancestry, a 2010 Grammy-nominatedalbum in the Best Contemporary World Musiccategory that was an unusual collaboration withNew England vocalist/banjoist/American folkethnomusicologist Tim Eriksen. Produced byJeff Levenson, the CD was released by HalfNote—the only Sosa disc not on the OaklandbasedOtá label.Even though Sosa has released multiple albumswithin a year’s time on a couple of occasions,he sells well, especially in France. Whilehis Grammy-nominated 2002 CD Sentir is arguablyhis top seller (an estimated 30,000 copiesworldwide), Price reports that today with digitaldistribution, the sales figures are more difficultto calculate.Sosa, who has been living in Barcelona forsome 12 years and has two kids (ages 5 and8), is planning to record his Kind Of Blue arrangementsin New York in May (he also performs aweek at the Blue Note, from May 3–8) with hisAfro-Electric quintet including Apfelbaum,German trumpeter Joo Kraus, bassist ChildoTomas, drummer Marque Gilmore and a specialguest, 78-year-old South African vocalist DavidSerrame. Known for changing his material upimprovisationally, Sosa will be delivering a differentsession than the show at Barcelona. Thetentative title is Alternative Africa, and the CDwill be issued late this year or early 2012.Meanwhile, Sosa is immersed in anotherexuberant project that he unveiled for Spanisheyes at the 2010 Barcelona Jazz Festival: his bigband adventure with the NDR Bigband of hisoriginals arranged by Brazilian great JaquesMorelenbaum. The album of this material,Ceremony, was released early in 2010. Sittingin the lounge area of the Gran Hotel Havana afew days before the performance at the majesticPalau de la Música, Sosa, draped in a baggypants and vest suit, with a blousy white shirtand dangling bracelets with shells on his wrists,says that the experience of the recording was adream come true. The opportunity came aboutbecause of a scheduling glitch when he wastouring with his quartet in Europe.“I was performing in Germany, then neededto leave that night to play in Poland the next day,”says Sosa. “We didn’t know we needed visas totravel there, so we were forced to miss our planeand stay overnight. So we hung out in a restaurantand drank a lot of wine. Stefan Gerdes of theNDR band asked me if I’d like to do a big bandalbum some day, and if so, who would I want toarrange the music. So, I said Jaques, who is anotherone of my heroes because of all the work hehad done with Brazilian musicians.”Off to Poland the next day, Sosa forgotabout the exchange. But Gerdes did not. Hecontacted Morelenbaum, who had first becomeexposed to Sosa when he heard the pianist atthe New Morning jazz club in Paris. He wasimpressed. In the liner notes of Ceremony, hewrites that the project was a dream gig for him,too: “I could not imagine I was going to meet anartist capable of making a complete and naturalsynthesis of what music is today on this planet.From that moment on, I began to dream aboutsharing the music that emanates from Omarwith such expressiveness. Now, here he comes,offering me not only his music and his freedom,but also the chance to listen to my arrangementsperformed by the fantastic ensemble.”Meanwhile, once Morelenbaum signed onto the project, Gerdes contacted Price, who relayedthe news to Sosa. “Wow, I could hardly rememberthat conversation,” he says. “But thankGod and all the spirits of my life. It turned outto be an amazing project. Jaques and I becamegood friends, and I learned so much about arrangingfrom him. He sent me titles of my songshe wanted to arrange, and I wrote two new pieces.I gave him the scores and said, ‘Fly.’ The resultis that my music sounds so different withall the complexities and voicings but still maintainswho I am. Funny thing is, Jaques told methat this was his first all-instrumental big bandalbum.”Apfelbaum marvels at Sosa’s eclectic oeuvre.“The vocabulary Omar uses is broad,” hesays. “That’s something that I find is a reflectionof the time we’re living in, but that many musiciansare not recognizing even though there isa lot more harmonic advancements and widerrhythmic variety than there was 30 years ago.The way Omar structures music is universal,but the foundation is always very Africa.”Santos, who continues to tour and recordwith Sosa on occasion, says, “Omar has an insatiableappetite for music. He’s like a creativesponge. He’s doing exactly what he set out to do:travel the world and play for many different audiences.He’s restless. He always has a new projecthe’s working on. And he attracts the most esotericand creative people in the world, whether it’s inEurope, Africa or the Middle East. We toured togetherin the Caribbean, Spain and Italy, and hemesmerized the audience in every show. He’s amagician. He brings magic to each project.”Certainly Sosa’s recording output reflectshis passion for diversity, with dates with a rangeof performers, including Venezuelan percussionistGustavo Ovalles, L.A.-based percussionistAdam Rudolph, clarinetist Paquito D’Riveraand trumpeter Paulo Fresu (a duo album is nowin the works). Another idea that Sosa was planningto embark on after his big band date inBarcelona was his Africa tour where he was goingto visit nine countries and record with traditionalmusicians from each. “The album will becalled Deeper Into The Tradition, which meanswe’ll be going deep,” says Sosa. “It’s going to beinteresting. For example, we’re going to Sudan,which is the tenth largest country by area in theworld, but they only have three pianos there,and all uprights. So that’s what I’ll be playing.”With a dance-like bounce to his step andrapid-fire zeal in his voice, Sosa is in surgemode, yet he has yet to fully break through inthe U.S. market. During his time in Barcelona,Sosa knew that Chano Domínguez was close tosigning with Blue Note to record his Kind OfBlue rendition. Is a major label deal somethingthat he’d be interested in?Usually voluminous in his responses to questions,Sosa shakes his head and bluntly says,“No.”Why not? “The way I look at the picture isthat if I feel something musically, I try to putthat out as a recording,” he says. “It’s a blessingto have my own label. I can put out whatever Iwant to, whenever. I record every message thatcomes to me. That’s why I have more than 20 recordsin a decade-and-a-half, and I own 100 percentof my publishing. I want my legacy to go tomy kids, not to a record company. Maybe I wouldhave a higher profile if I did a record on a majorlabel, and I’d get more publicity and attention.But I figure the more you control your own music,the more opportunities you can have in thefuture.” DBFEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT 33

John McNeilAll WitBy Jim MacnieThey come each week, and each week they make you chuckle. Sometimes they readlike this: “Wednesday is Tiki Barber’s birthday. To celebrate, the band is moving toan earlier start time of 8:30. In addition, the audience will be asked to participate inblocking and tackling drills between sets. Shoulder pads will be provided, but everyoneshould bring their own helmet and cleats. No wagering.”And sometimes they read like this: “To celebrate the 120th anniversaryof the official opening of the Eiffel Tower, the band will present worksby French composers such as François Rosolineau, Thelonious-ClaudeLeMonk and Jean Coltraigne. There’s no minimum, so pay a cover, hangout for three sets and have some brie. Or some epoisses. Scratch that:epoisses smells like death, so vile that it’s actually illegal to carry it on theParis Métro.”They’re header paragraphs of invitations to see John McNeil’s variousbands at Puppets, a Brooklyn jazz club. The trumpeter doesn’t like to doanything without giving it a bit of flair, so for several years now, his weeklygig reminders have been crazed and cool. On his 61st birthday, the textpromised a red velvet cake so good, “It will make you slap your grandma.”Ask anyone who knows McNeil, and they’ll mention the fact that he’spart wag, part wiseass and all wit. A string of quips often shoots from thebandstand when the now-62-year-old brings his freebop antics to an audience.He’s just as quick with a snarky comment as he is with trumpet flourish.The first time I saw him play, he intro’d Russ Freeman’s “Batter Up”with a gleefully sarcastic mention of how lame the Mets were. After animpromptu gig with other New York jazzers last spring, while everyonefrom Tony Malaby to Rob Garcia was congratulating each other for somenifty coordination during a totally abstract piece, McNeil told his mateswith a smile, “You guys were lost a lot of the time, but yeah, it was cool.”They expected nothing less. Everyone knows that he’s a guy who has levityfor lunch.“When we made East Coast Cool,” says saxophonist Allan Chase,“we took fun photographs of ourselves dressed in suits, acting like Chetand Gerry. When it was time to decide which of the shots to use, Johnstarted sending me these PhotoShopped variations of the cover with themost hilarious fake album titles, many of them quite obscene—about 25came through before he was done, and each was more outrageous thanthe last.”The 2006 record Chase alludes to was a novel date, opening the doorto a new slant on the 1950s West Coast sound, which is often typified bythe darting interplay of the musicians he mentioned, Mr. Baker and Mr.Mulligan. McNeil conceptualized the approach, putting a modern spin onan orthodox repertory. He’s long appreciated the lithe intricacies of cooljazz, having shared bills with Baker and done time in Mulligan’s large ensembles.But he also digs the open territories of free-jazz, and has lots ofskills when it comes to launching investigatory solos. East Coast Cool’sblend of chipper melodies and mercurial improvs was unique. Its tunes,mostly written by McNeil to bridge the particulars of each element, ingeniouslystraddled the two approaches.“When he handed me my music folder, the cover title read ‘CGOA,’ recallsChase. “I said, ‘John, what’s that mean?’ ‘Chet and Gerry on acid,’he deadpanned.”A similar whimsy has been driving the otherwise serious music projectsMcNeil has helmed for the last few years. His latest Sunnyside album,made in collaboration with tenor saxophonist Bill McHenry, is calledChill Morn, He Climb Jenny (yep, it sounds dirty, but it’s an anagram oftheir names). Like Rediscovery, the disc that preceded it, the program containsa scad of unique spins on actual West Coast nuggets that the pairhave refined during the last few years. Freeman is a central figure here:Everything from “Band Aid” to “Happy Little Sunbeam” to “Bea’s Flat” ispart of the McNeil–McHenry book. Those titles are surrounded by WilberHarden, Jimmy Van Heusen and George Wallington ditties. It’s a tack thathas earned the trumpeter wider visibility. A few years ago the New YorkTimes proclaimed the pair’s weekly interpretation of such jewels to be“one of the best jazz events in the city.”34 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011

Mike FiggisFEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT 35

Composer Nicholas Urie has been arranging some of McNeil’s tunesand co-leading a big band with him. “There are two types of older people,”he says, “those who look forward and those who look back. John, as a rule,looks forward. One the most effective ways he does it is by putting himselfin situations where he might not know entirely what’s going to happen.Some people his age get confrontational when it comes to doing things in away other than the norm. He’s interested in reimagining his career and theway he relates to improvisation and jazz in general.”Rolling through the book at Manhattan’s Cornelia Street Café (whereChill Morn was recorded live), the group, which features bassist Joe Martinand drummer Jochen Rueckert, recently found ways to balance their materials.McHenry is utterly willing to stroll down avenues where anythinggoes. His solos, often fascinating, have a private feel, sometimes taking afew seconds to reveal their inner logic. His exchanges with McNeil are deft;their camaraderie is such that the counterpoint demanded by the arrangementsis dead-on. The two weave in and out of each other, offering a sweetsymmetry. McNeil is agile as he moves around his horn. His solos can besly or puckish. Seldom are they arcane, though. The relative simplicity ofthe melodies gives even the most complicated maneuvers a breezy quality.“Those West Coast tunes are relentlessly cheery,” says McNeil, “younever hear any sturm und drang coming from out there; it’s sunshine, optimism,vitamin D. In many of these tunes there’s almost a Mozartian lightness.”He starts singing Nachtmusic’s “Allegro,” and segues it into Baker’s“A Dandy Line.” “Back in New York, everyone is in a minor key, everyonethinks they’re going to die. But not out there. I wonder if [Charles] Mingusbrought his own cloud with him when he moved to Mill Valley—that’s avery bucolic place. ‘Think it’s going to rain?’ ‘Maybe; I see lightning rightabove Mingus’ house.’ Even the California song titles were cute: ‘Shank’sPranks’ and things like that. Back East we’d have titles like ‘Black Death’or ‘Relentless Cough.’”McNeil knows a tad about bad weather. He’s spent a good chunk of hislife battling the constraints of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, which affectsthe body’s muscles by messing with its neural system. As a kid in Yreka,Calif., he wore braces all over his body. Taunts from bullies were the norm,and McNeil believes that some of his humor was sharpened by the guys whoteased him. He took some punches, both verbal and physical, and gave backa few as well. He saw his wit as an armor of sorts. “Being handicapped in asmall town doesn’t get you far,” he says. “It’s better to be funny.”As a child he came across Louis Armstrong on TV, was swayed by thecharisma and got himself a trumpet. When he was in his mid-teens, theCMT’s impact subsided. Befriending a local newspaper editor who hadonce gigged with Red Nichols, McNeil received encouragement for hisown playing. He connected with big bands and fell deeper into jazz. Hetended to like the new stuff. He believes he was the only person in Yrekawho bought Miles Davis’ ESP the week it was released.He’s a brainiac, and after hitting a home run on his SATs, IBM tried torecruit him. McNeil decided to stick with jazz because there were more opportunitiesto connect with the opposite sex. He hit New York in the early’70s, snuggled into the Thad Jones–Mel Lewis Orchestra and played a bitwith Horace Silver. He started getting his own gigs, too. Being in shape becamea priority. When he first met his longtime sweetie, Lolly Bienenfeld,she lived on the 43rd floor of a Manhattan high-rise; McNeil would run upthe stairs to stay in shape.One day, out of the blue, the CMT emerged again. This time the diseasehad snuck its way into his face and his diaphragm. He made physicalchanges to keep his chops together, but it was an uphill battle. Another blowwas struck when he discovered that two of his spinal vertebrae had disintegrated.Can you say massive, constant pain? A 14-hour operation helpedsave him from death, and afterwards the proud surgeon presented him tocolleagues as part of a “here’s what’s possible” medical forum. Time for avictory dance, right? Wait, we’re not done yet.In the mid-’80s the trumpeter lost control of his right hand and couldn’tfinger the horn with any accuracy. Fellow musicians told him that should bethe final straw, but with Bienenfeld’s support and a sense of determinationhoned during his childhood days, he learned to play the trumpet with his36 DOWNBEAT FEBRUARY 2011