Finest Hour - Winston Churchill

Finest Hour - Winston Churchill

Finest Hour - Winston Churchill

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

“GOOD VOYAGE — CHURCHILL”<br />

THE JOURNAL OF WINSTON CHURCHILL<br />

SUMMER 2011 • NUMBER 151<br />

$5.95 / £3.50

i<br />

THE CHURCHILL CENTRE & CHURCHILL WAR ROOMS<br />

UNITED STATES • CANADA • UNITED KINGDOM • AUSTRALIA • PORTUGAL<br />

PATRON: THE LADY SOAMES LG DBE • WWW.WINSTONCHURCHILL.ORG<br />

Founded in 1968 to educate new generations about the<br />

leadership, statesmanship, vision and courage of <strong>Winston</strong> Spencer <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

® ®<br />

MEMBER, NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR HISTORY EDUCATION • RELATED GROUP, AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION<br />

SUCCESSOR TO THE WINSTON S. CHURCHILL STUDY UNIT (1968) AND INTERNATIONAL CHURCHILL SOCIETY (1971)<br />

BUSINESS OFFICES<br />

200 West Madison Street<br />

Suite 1700, Chicago IL 60606<br />

Tel. (888) WSC-1874 • Fax (312) 658-6088<br />

info@winstonchurchill.org<br />

CHURCHILL MUSEUM<br />

AT THE CHURCHILL WAR ROOMS<br />

King Charles Street, London SW1A 2AQ<br />

Tel. (0207) 766-0122 • http://cwr.iwm.org.uk/<br />

CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD<br />

Laurence S. Geller<br />

lgeller@winstonchurchill.org<br />

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR<br />

Lee Pollock<br />

lpollock@winstonchurchill.org<br />

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER<br />

Daniel N. Myers<br />

dmyers@winstonchurchill.org<br />

BOARD OF TRUSTEES<br />

The Hon. Spencer Abraham • Randy Barber<br />

Gregg Berman • David Boler • Paul Brubaker<br />

Donald W. Carlson • Randolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

David Coffer • Manus Cooney • Lester Crown<br />

Sen. Richard J. Durbin • Kenneth Fisher<br />

RAdm. Michael T. Franken USN • Laurence S. Geller<br />

Rt Hon Sir Martin Gilbert CBE • Richard C. Godfrey<br />

Philip Gordon • D. Craig Horn • Gretchen Kimball<br />

Richard M. Langworth CBE • Diane Lees • Peter Lowy<br />

Rt Hon Sir John Major KG CH • Lord Marland<br />

J.W. Marriott Jr. • Christopher Matthews<br />

Sir Deryck Maughan • Harry E. McKillop • Jon Meacham<br />

Michael W. Michelson • John David Olsen • Bob Pierce<br />

Joseph J. Plumeri • Lee Pollock • Robert O’Brien<br />

Philip H. Reed OBE • Mitchell Reiss • Ken Rendell<br />

Elihu Rose • Stephen Rubin OBE<br />

The Hon. Celia Sandys • The Hon. Edwina Sandys<br />

Sir John Scarlett KCMG OBE<br />

Sir Nigel Sheinwald KCMG • Mick Scully<br />

Cita Stelzer • Ambassador Robert Tuttle<br />

HONORARY MEMBERS<br />

Rt Hon David Cameron, MP<br />

Rt Hon Sir Martin Gilbert CBE<br />

Robert Hardy CBE<br />

The Lord Heseltine CH PC<br />

The Duke of Marlborough JP DL<br />

Sir Anthony Montague Browne KCMG CBE DFC<br />

Gen. Colin L. Powell KCB<br />

Amb. Paul H. Robinson, Jr.<br />

The Lady Thatcher LG OM PC FRS<br />

FRATERNAL ORGANIZATIONS<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> Archives Centre, Cambridge<br />

The <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> Memorial Trust, UK, Australia<br />

Harrow School, Harrow-on-the-Hill, Middlesex<br />

America’s National <strong>Churchill</strong> Museum, Fulton, Mo.<br />

COMMUNICATIONS<br />

John David Olsen, Director and Webmaster<br />

Chatlist Moderators: Jonah Triebwasser, Todd Ronnei<br />

http://groups.google.com/group/<strong>Churchill</strong>Chat<br />

Twitter: http://twitter.com/<strong>Churchill</strong>Centre<br />

ACADEMIC ADVISERS<br />

Prof. James W. Muller,<br />

Chairman, afjwm@uaa.alaska.edu<br />

University of Alaska, Anchorage<br />

Prof. Paul K. Alkon, University of Southern California<br />

Rt Hon Sir Martin Gilbert CBE, Merton College, Oxford<br />

Col. David Jablonsky, U.S. Army War College<br />

Prof. Warren F. Kimball, Rutgers University<br />

Prof. John Maurer, U.S. Naval War College<br />

Prof. David Reynolds FBA, Christ’s College, Cambridge<br />

Dr. Jeffrey Wallin,<br />

American Academy of Liberal Education<br />

LEADERSHIP AND SUPPORT<br />

NUMBER TEN CLUB<br />

Contributors of $10,000+ per year<br />

Skaddan Arps • Boies, Schiller & Flexner LLP<br />

Mr. & Mrs. Jack Bovender • Carolyn & Paul Brubaker<br />

Mrs. <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong> • Lester Crown<br />

Kenneth Fisher • Marcus & Molly Frost<br />

Laurence S. Geller • Rick Godfrey • Philip Gordon<br />

Martin & Audrey Gruss • J.S. Kaplan Foundation<br />

Gretchen Kimball • Susan Lloyd • Sir Deryck Maughan<br />

Harry McKillop • Elihu Rose • Michael Rose<br />

Stephen Rubin • Mick Scully • Cita Stelzer<br />

CHURCHILL CENTRE ASSOCIATES<br />

Contributors to The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre Endowment, of<br />

$10,000, $25,000 and $50,000+, inclusive of bequests.<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> Associates<br />

The Annenberg Foundation • David & Diane Boler<br />

Samuel D. Dodson • Fred Farrow • Marcus & Molly Frost<br />

Mr. & Mrs. Parker Lee III • Michael & Carol McMenamin<br />

David & Carole Noss • Ray & Patricia Orban<br />

Wendy Russell Reves • Elizabeth <strong>Churchill</strong> Snell<br />

Mr. & Mrs. Matthew Wills • Alex M. Worth Jr.<br />

Clementine <strong>Churchill</strong> Associates<br />

Ronald D. Abramson • <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Jeanette & Angelo Gabriel• Craig & Lorraine Horn<br />

James F. Lane • John Mather • Linda & Charles Platt<br />

Ambassador & Mrs. Paul H. Robinson Jr.<br />

James R. & Lucille I. Thomas • Peter J. Travers<br />

Mary Soames Associates<br />

Dr. & Mrs. John V. Banta • Solveig & Randy Barber<br />

Gary & Beverly Bonine • Susan & Daniel Borinsky<br />

Nancy Bowers • Lois Brown<br />

Carolyn & Paul Brubaker • Nancy H. Canary<br />

Dona & Bob Dales • Jeffrey & Karen De Haan<br />

Gary Garrison • Ruth & Laurence Geller<br />

Fred & Martha Hardman • Leo Hindery, Jr.<br />

Bill & Virginia Ives • J. Willis Johnson<br />

Jerry & Judy Kambestad • Elaine Kendall<br />

David M. & Barbara A. Kirr<br />

Barbara & Richard Langworth • Phillip & Susan Larson<br />

Ruth J. Lavine • Mr. & Mrs. Richard A. Leahy<br />

Philip & Carole Lyons • Richard & Susan Mastio<br />

Cyril & Harriet Mazansky • Michael W. Michelson<br />

James & Judith Muller • Wendell & Martina Musser<br />

Bond Nichols • Earl & Charlotte Nicholson<br />

Bob & Sandy Odell • Dr. & Mrs. Malcolm Page<br />

Ruth & John Plumpton • Hon. Douglas S. Russell<br />

Daniel & Suzanne Sigman • Shanin Specter<br />

Robert M. Stephenson • Richard & Jenny Streiff<br />

Gabriel Urwitz • Damon Wells Jr.<br />

Jacqueline Dean Witter<br />

ALLIED NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS<br />

_____________________________________<br />

INTL. CHURCHILL SOCIETY CANADA<br />

14 Honeybourne Crescent, Markham ON, L3P 1P3<br />

Tel. (905) 201-6687<br />

www.winstonchurchillcanada.ca<br />

Ambassador Kenneth W. Taylor, Honorary Chairman<br />

CHAIRMAN<br />

Randy Barber, randybarber@sympatico.ca<br />

VICE-CHAIRMAN AND RECORDING SECRETARY<br />

Terry Reardon, reardont@rogers.com<br />

TREASURER<br />

Barrie Montague, bmontague@cogeco.ca<br />

BOARD OF DIRECTORS<br />

Charles Anderson • Randy Barber • David Brady<br />

Peter Campbell • Dave Dean • Cliff Goldfarb<br />

Robert Jarvis • Barrie Montague • Franklin Moskoff<br />

Terry Reardon • Gordon Walker<br />

_____________________________________<br />

INTL. CHURCHILL SOCIETY PORTUGAL<br />

João Carlos Espada, President<br />

Universidade Católica Portuguesa<br />

Palma de Cima 1649-023, Lisbon<br />

jespada@iep.ucp.pt • Tel. (351) 21 7214129<br />

__________________________________<br />

THE CHURCHILL CENTRE AUSTRALIA<br />

Alfred James, President<br />

65 Billyard Avenue, Wahroonga, NSW 2076<br />

abmjames1@optusnet.com.au • Tel. 61-2-9489-1158<br />

___________________________________________<br />

THE CHURCHILL CENTRE - UNITED KINGDOM<br />

Allen Packwood, Executive Director<br />

c/o <strong>Churchill</strong> Archives Centre<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> College, Cambridge, CB3 0DS<br />

allen.packwood@chu.cam.ac.uk • Tel. (01223) 336175<br />

THE BOARD (*Trustees)<br />

The Hon. Celia Sandys, Chairman*<br />

David Boler* • Randolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong>*<br />

David Coffer • Paul H. Courtenay<br />

Laurence Geller* • Philip Gordon<br />

Scott Johnson* • The Duke of Marlborough JP DL<br />

The Lord Marland* • Philippa Rawlinson<br />

Philip H. Reed OBE* • Stephen Rubin OBE<br />

Cita Stelzer • Anthony Woodhead CBE FCA*<br />

HON. MEMBERS EMERITI<br />

Nigel Knocker OBE • David Porter<br />

___________________________________________<br />

THE CHURCHILL CENTRE - UNITED STATES<br />

D. Craig Horn, President<br />

5909 Bluebird Hill Lane<br />

Weddington, NC 28104<br />

dcraighorn@carolina.rr.com • Tel. (704) 844-9960<br />

________________________________________________<br />

CHURCHILL SOCIETY FOR THE ADVANCEMENT<br />

OF PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRACY<br />

www.churchillsociety.org<br />

Robert A. O’Brien, Chairman<br />

3050 Yonge Street, Suite 206F<br />

Toronto ON, M4N 2K4<br />

ro’brien@couttscrane.com • Tel. (416) 977-0956

CONTENTS<br />

The Journal of<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

<br />

Number 151<br />

Summer 2011<br />

Packwood, 10<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>, 14<br />

COVER<br />

Admiralty Christmas card, 1941, showing HMS Prince of Wales returning <strong>Churchill</strong> from the<br />

Atlantic Charter conference with Roosevelt, August 1941. Flying from the masts are the signal flags<br />

PYU (international code for “Good Voyage”) and CHURCHILL. We cannot prove, but are fairly<br />

certain, that the PM is standing on the portside wing. From a painting by William McDowell,<br />

probably commmissioned by the card producer Raphael Tuck. Reproduced by kind courtesy of the<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> Archives Centre, Cambridge, Sir John Martin Papers (MART-3). Story on page 18.<br />

ARTICLES<br />

Theme of the Issue: “The Special Relationship”<br />

8/ What Is Left of the Special Relationship • Richard M. Langworth<br />

10/ The Power of Words and Machines • Allen Packwood<br />

12/ Why Study <strong>Churchill</strong> The American Alliance, for One Thing • Martin Gilbert<br />

14/ Reflections on America • <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

16/ What He Saw and Heard in Georgia • William L. Fisher<br />

18/ Cover Story: “Good Voyage—<strong>Churchill</strong>” • H.V. Morton<br />

19/ The Meeting with President Roosevelt, August 1941 • <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

20/ Hands Across the Atlantic: Edward R. Murrow • Fred Glueckstein<br />

22/ “All in the Same Boat” • Ambassador Raymond Seitz<br />

27/ Is This the Man • Charles Miner Cooper<br />

28/ William A. Rusher 1923-2011 • The Editor with Larry P. Arnn<br />

29/ “The Truth is Great, and Shall Prevail” • William A. Rusher<br />

55/ <strong>Churchill</strong>iana: The Potted Special Relationship • Douglas Hall<br />

Randolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong> Centenary 1911-2011<br />

32/ “The Beast of Bergholt”: Remembering Randolph • Martin Gilbert<br />

34/ Randolph by His Contemporaries • Compiled by Dana Cook<br />

36/ Washington, 9 April 1963: Randolph’s Day • Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis<br />

<br />

38/ <strong>Churchill</strong> on Clemenceau: His Best Student Part II • Paul Alkon<br />

44/ “Golden Eggs,” Part III: Intelligence and Closing the Ring • Martin Gilbert<br />

Seitz, 22<br />

Onassis, 36<br />

BOOKS, ARTS & CURIOSITIES<br />

50/ Former Naval Persons and Places • Christopher M. Bell:<br />

Historical Dreadnoughts, by Barry Gough and <strong>Churchill</strong>’s Dilemma, by Graham Clews<br />

51/ <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>: Walking with Destiny • Film Review by David Druckman<br />

52/ <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>: War Leader, by Bill Price • Max E. Hertwig<br />

53/ Pol Roger Champagne: Another Look • Daniel Mehta<br />

56/ Harold Nicolson and His Diaries • James Lancaster<br />

60/ Education: Finding Answers for National History Day • The Editor<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

2/ The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre • 4/ Despatch Box • 5/ Around & About • 6/ Datelines<br />

6/ Quotation of the Season • 8/ From the Editor • 14/ Wit & Wisdom • 27/ Poetry<br />

30/ Action This Day • 37/ Riddles, Mysteries, Enigmas • 43/ Moments in Time<br />

55/ <strong>Churchill</strong>iana • 62/ <strong>Churchill</strong> Quiz • 63/ Regional Directory<br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 3

D E S P A T C H B O X<br />

Number 151 • Summer 2011<br />

ISSN 0882-3715<br />

www.winstonchurchill.org<br />

____________________________<br />

Barbara F. Langworth, Publisher<br />

barbarajol@gmail.com<br />

Richard M. Langworth, Editor<br />

rlangworth@winstonchurchill.org<br />

Post Office Box 740<br />

Moultonborough, NH 03254 USA<br />

Tel. (603) 253-8900<br />

December-March Tel. (242) 335-0615<br />

__________________________<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Paul H. Courtenay, David Dilks,<br />

David Freeman, Sir Martin Gilbert,<br />

Edward Hutchinson, Warren Kimball,<br />

Richard Langworth, Jon Meacham,<br />

Michael McMenamin, James W. Muller,<br />

John Olsen, Allen Packwood,<br />

Terry Reardon, Suzanne Sigman,<br />

Manfred Weidhorn<br />

Senior Editors:<br />

Paul H. Courtenay<br />

James W. Muller<br />

News Editor:<br />

Michael Richards<br />

Contributors<br />

Alfred James, Australia<br />

Terry Reardon, Dana Cook, Canada<br />

Antoine Capet, James Lancaster, France<br />

Paul Addison, Sir Martin Gilbert,<br />

Allen Packwood, United Kingdom<br />

David Freeman, Fred Glueckstein,<br />

Ted Hutchinson, Warren F. Kimball,<br />

Justin Lyons, Michael McMenamin,<br />

Robert Pilpel, Christopher Sterling,<br />

Manfred Weidhorn, United States<br />

___________________________<br />

• Address changes: Help us keep your copies coming!<br />

Please update your membership office when<br />

you move. All offices for The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre<br />

and Allied national organizations are listed on<br />

the inside front cover.<br />

__________________________________<br />

<strong>Finest</strong> <strong>Hour</strong> is made possible in part through the<br />

generous support of members of The <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Centre and Museum, the Number Ten Club,<br />

and an endowment created by the <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Centre Associates (page 2).<br />

___________________________________<br />

Published quarterly by The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre,<br />

offering subscriptions from the appropriate<br />

offices on page 2. Permission to mail at nonprofit<br />

rates in USA granted by the United<br />

States Postal Service, Concord, NH, permit<br />

no. 1524. Copyright 2011. All rights reserved.<br />

Produced by Dragonwyck Publishing Inc.<br />

CASABLANCA LETTERS:<br />

IT WAS WEYGAND!<br />

I was intrigued by whether Rick’s<br />

“Letters of Transit” in Casablanca (FH<br />

150: 49) cite Darlan, not de Gaulle, as<br />

the French authority in the European<br />

version. We have a DVD sold in<br />

France with English and French subtitles.<br />

My wife easily found the passage<br />

with Peter Lorre speaking about the<br />

signature on the Letters of Transit with<br />

his exaggerated German accent. We<br />

heard neither “de Gaulle,” nor did we<br />

hear “Darlan,” although the English<br />

subtitles read “de Gaulle.” I thought it<br />

sounded more like “Weygand,” not<br />

realising this would lead us to the<br />

correct track. My wife then found the<br />

answer on the Internet Movie Database<br />

(http:// imdb.to/mJvlBS):<br />

“Incorrectly regarded as goofs: It<br />

is widely believed that Ugarte [Lorre]<br />

clearly says that the Letters of Transit<br />

are ‘signed by General de Gaulle.’ This<br />

would have rendered them useless in<br />

Casablanca, as de Gaulle was the leader<br />

of the Free French forces which were<br />

actively fighting against the Nazibacked<br />

Vichy regime that controlled<br />

Casablanca. De Gaulle's name is shown<br />

on the English and Spanish DVD/Blu-<br />

Ray subtitles. However, Peter Lorre<br />

actually names General Weygand<br />

(Vichy Minister of Defence, whatever<br />

that means in an occupied country).<br />

The French subtitles have it correct.”<br />

ANTOINE CAPET, ROUEN, FRANCE<br />

SENATOR BYRD<br />

In Winchester, Virginia, I visited<br />

Senator Harry Byrd, who spoke at our<br />

1991 conference in Richmond. He is<br />

in fine form and enjoys <strong>Finest</strong> <strong>Hour</strong>.<br />

We talked at length about <strong>Churchill</strong>’s<br />

two visits to Richmond; his stories of<br />

the 1929 visit are as funny as ever. He<br />

expressed the view that <strong>Churchill</strong> was<br />

“saved” for the great task that befell<br />

him in 1940.<br />

Sen. Byrd expressed appreciation<br />

for Celia Sandys’s visit to Winchester<br />

several years ago. We also talked of his<br />

famous uncle, Admiral Richard Byrd,<br />

whose Boston home at 9 Brimmer<br />

Street I had visited a week before.<br />

Other than Lady Soames, I<br />

cannot think of anyone with an “older”<br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 4<br />

memory of Sir <strong>Winston</strong> than Harry<br />

Byrd. It goes back eighty-two years.<br />

RICHARD H. KNIGHT, JR., NASHVILLE, TENN.<br />

Senator Byrd and Richard Knight<br />

VON MANSTEIN<br />

In FH 150 I read “How Guilty<br />

Were the German Field Marshals” As<br />

a schoolmaster who helps sixth formers<br />

with their coursework, I admire your<br />

attempt to steer people away from<br />

Wikipedia. It’s fine for checking basic<br />

things like birth dates, but not for<br />

much more. Any of my pupils who rely<br />

on it as their sole source for information<br />

will get very short shrift from me<br />

(and poor marks for research).<br />

I like to point students towards<br />

specific books. For Manstein there is an<br />

outstanding new biography, Manstein:<br />

Hitler’s Greatest General, by Mungo<br />

Melvin, a serving British general<br />

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson), now in<br />

paperback. Two chapters cover his<br />

postwar life, particularly his trial. This<br />

would be ideal for any A-Level (or<br />

equivalent) student. Incidentally, it has<br />

the best maps of any military history<br />

book I’ve read in years.<br />

Other sources are von Manstein’s<br />

memoirs, Lost Victories (Methuen,<br />

1958, abridged from the German original);<br />

Erich von Manstein by Robert<br />

Forczyk (Osprey, 2010); the Manstein<br />

essay by Field Marshal Lord Carver in<br />

Hitler’s Generals (Weidenfeld &<br />

Nicolson, 1989); Liddell Hart: A Study<br />

of His Military Thought, by Brian<br />

Bond (Cassell, 1977, useful for L-H’s<br />

contribution to the trial); Alchemist of<br />

War: The Life of Basil Liddell Hart, by<br />

Alex Danchev (Weidenfeld &<br />

Nicolson, 1998); and Liddell Hart’s

The Other Side of the Hill (Cassell,<br />

1948). I am sure a similar list for<br />

Kesselring could be constructed.<br />

ROBIN BRODHURST, READING, BERKS.<br />

FOND MEMORIES<br />

Thank you for the review of<br />

Heather White-Smith’s My Years with<br />

the <strong>Churchill</strong>s. Barbara Langworth’s<br />

comments are entirely fair. The stories<br />

it contains are domestic ones, as they<br />

occurred, and were written into her<br />

diary. However, contrary to the review,<br />

pages 21-22 do indeed discuss WSC’s<br />

1953 stroke and how it was kept quiet.<br />

Heather, Grace Hamblin and Jo<br />

Sturdee (later Lady Onslow) used to<br />

lunch together regularly. The last time<br />

Grace went to Chartwell was when we<br />

took her to hear Roy Jenkins at the<br />

launch of his biography. We often saw<br />

Jo, as she lived near Heather’s daughter<br />

in Oxfordshire. We miss both of them.<br />

The saddest thing was that when the<br />

three were together so many tales were<br />

regaled, only to be forgotten and lost<br />

to posterity. I just so wish I had taken a<br />

tape recorder on those occasions!<br />

You might also be interested to<br />

know that Heather has given several<br />

talks, based on her book, for which she<br />

was helped with her presentation skills<br />

by Robert Hardy.<br />

HENRY WHITE-SMITH, SUNNINGDALE, BERKS.<br />

AROUND & ABOUT<br />

Conservative radio talk-czar<br />

Rush Limbaugh ran this doctored<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> photo on his website. New<br />

Jersey Governor Chris Christie looks<br />

like hes ordering two pizzas. If he could lose that<br />

double chin he would poll 10% more favorably.<br />

Accompanying the photo was a transcript with a<br />

caller, lamenting that Christie, unlike <strong>Churchill</strong>, refuses<br />

to run for president when hes needed. Limbaugh praised <strong>Churchill</strong> for stepping<br />

forward for his country in World War II.<br />

But <strong>Churchill</strong> didnt exactly step forward. Hed always been available. It<br />

was the government that wasnt having him—until the chips were down and<br />

there was no one else. Nor was <strong>Churchill</strong>, per Limbaugh, alone in opposing<br />

Hitler. There were Anthony Eden and Alfred Duff Cooper, among others.<br />

The caller had a point that there is no <strong>Churchill</strong> among candidates for<br />

President (or indeed for Prime Minister, nor has there been since the war,<br />

with the possible exception of 1979). Every four years we see people proposing<br />

to run who bring to mind Denis Healys comment that being attacked<br />

by Sir Geoffrey Howe was akin to being savaged by a dead sheep.<br />

<br />

Daily Telegraph political correspondent James Kirkup reports that<br />

another would-be <strong>Churchill</strong> has bitten the dust: Defence Secretary Liam<br />

Fox was criticized for taking members of his staff to a Whitehall pub after<br />

the British intervention in Libya. “Dr. Fox, a sociable type, pointed out that<br />

he had not drunk alcohol during Lent, only breaking his fast over Libya. I<br />

dont think it was unreasonable, he said. Its a bit like asking <strong>Churchill</strong> if he<br />

regrets having a drink during World War II.”<br />

Labour MPs quickly homed in, Kirkup wrote: Shadow Defence Minister<br />

Kevan Jones said, “This is yet another demonstration of the over-inflated<br />

opinion Liam Fox has of himself.” Michael Dugher, his colleague, added,<br />

“Liam Fox is no <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>.” Ah well, better men than you, Fox. <br />

Editor’s response: Thank you for<br />

the gracious comments, under the circumstances!<br />

We were wrong about the<br />

1953 stroke; see Errata, page 7. Those<br />

interested in Mrs. White-Smith’s talks<br />

should email henry@woosier.co.uk.<br />

DR. WHO<br />

Although not especially a Dr.<br />

Who fan, I have seen the Cabinet War<br />

Rooms episode and “The Making of<br />

Dr. Who.” So I found the Dr. Who<br />

exam answer (FH 150: 8) a refreshing<br />

amusement. This web page describes<br />

“River Song” and near the end,<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>'s role in getting the Van<br />

Gogh painting, and the “Pandora<br />

Opening”: http://bit.ly/hxyt02.<br />

GRACE FILBY, REIGATE, SURREY<br />

Dr. Who has always had a special<br />

love for Britain and the Monarchy. In<br />

.<br />

the David Tennant series, <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

calls him on a phone in the Tardis and<br />

he flits back to World War II to help.<br />

He's rumored to have had an affair<br />

with the Virgin Queen Elizabeth,<br />

revealed when he meets Elizabeth X (a<br />

gun-toting gal who saves his bacon).<br />

But I believe the Van Gogh painting<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> gives Dr. Who is in a later<br />

series which ended in December 2010,<br />

and is only seen as part of a flashback.<br />

This is cool to read!<br />

CHARLOTTE THIBAULT, CONCORD, N.H<br />

DISLOYAL TOASTS<br />

At the March Charleston meeting<br />

it came to my attention that several<br />

present refused a request to give the<br />

Loyal Toast to the President of the<br />

United States, and one even admitted<br />

it. The context of that rejection was<br />

clearly intense personal dislike (stronger<br />

words were used) for the incumbent.<br />

Rude behavior is not limited to<br />

the present. I understand that in 1986<br />

a prominent member was heard to<br />

toast “The Presidency,” while in 1998<br />

there were shouts of “No!” and a few<br />

years later “Bush lied!” Perhaps 1986<br />

was forgivable: the toast is to an Office<br />

of State. But not so the other instances.<br />

I leave it to readers’ imaginations<br />

to speculate how <strong>Churchill</strong> would have<br />

characterized such behavior. He had no<br />

truck with petty personal politics.<br />

Loyalty to the office—monarch, prime<br />

minister, president, whatever—was a<br />

hallmark of his character and style.<br />

Lacking his way with words, I will<br />

simply say that, if these stories are true,<br />

I am ashamed of the persons involved,<br />

and of their disgraceful and fundamentally<br />

unpatriotic action.<br />

WARREN F. KIMBALL, JOHN ISLAND, S.C. <br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 5

DAT E L I N E S<br />

CHURCHILL ON THE ROYAL WEDDING<br />

LONDON, OCTOBER 22ND, 1947— “I am in<br />

entire accord with what the Prime<br />

Minister has said about Princess<br />

Elizabeth and about the qualities<br />

which she has already shown, to<br />

use his words, ‘of unerring graciousness<br />

and understanding and<br />

of human simplicity.’<br />

He is indeed right in declaring that<br />

these are among the characteristics of<br />

the Royal House. I trust that everything<br />

that is appropriate will be done<br />

by His Majesty's Government to mark<br />

this occasion of national rejoicing.<br />

‘One touch of nature makes the whole<br />

world kin,’ and millions will welcome<br />

this joyous event as a flash of colour<br />

on the hard road we have to travel.<br />

From the bottom of our hearts, the<br />

good wishes and good will of the<br />

British nation flow out to the Princess<br />

and to the young sailor who are so<br />

soon to be united in the bonds of holy<br />

matrimony. That they may find true<br />

happiness together and be guided on<br />

the paths of duty and honour is the<br />

prayer of all.”<br />

—WSC (HIS QUOTATION IS FROM<br />

SHAKESPEARE’S TROILUS AND CRESSIDA)<br />

LONDON, APRIL 29TH, 2011— If the Great<br />

Man woke up from his “black velvet—<br />

eternal sleep,” perhaps to enjoy a cigar<br />

and a cognac during the pageantry in<br />

London, he might have felt a sense of<br />

satisfaction, and invoked his favorite<br />

Boer expression, Alles sal reg kom—<br />

“All will come right.” The words he<br />

spoke sixty-four years ago at another<br />

Royal Wedding have stood the test of<br />

time. “We could not have had a better<br />

King,” he told Anthony<br />

Montague Browne in 1953:<br />

“And now we have this<br />

splendid Queen.”<br />

The road has indeed<br />

been hard these six decades<br />

of her reign, but “unerring<br />

graciousness” and “human<br />

simplicity” have marked her<br />

every step along the way.<br />

We wish the couple a happy<br />

life and a sense of responsibility.<br />

Live long, and<br />

prosper. RML<br />

FALSE ALARM AT<br />

33 ECCLESTON SQUARE<br />

LONDON, FEBRUARY 21ST— Stefan<br />

Buczacki, author of <strong>Churchill</strong> and<br />

Chartwell (FH 138), left home to give<br />

a talk on <strong>Churchill</strong>’s homes to a civic<br />

society. “I returned to find an alarming<br />

email sent a few minutes after my<br />

departure to the effect that <strong>Churchill</strong>'s<br />

former London house at 33 Eccleston<br />

Square had been destroyed by fire<br />

during the day. The London Fire<br />

Brigade confirmed that there had<br />

indeed been a major fire in Eccleston<br />

Square but the neighbouring house to<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>’s former home at Number<br />

33 was the one affected; terrible for<br />

the owners, but a relief for historians.<br />

“<strong>Churchill</strong> took over 33<br />

Eccleston Square in March 1909 after<br />

selling his first home at 12 Bolton<br />

Street. The Square was created in 1835<br />

by Thomas Cubitt, who took a lease<br />

from the Duke of Westminster to<br />

provide rather grand neo-classical<br />

houses for the aristocracy and successful<br />

professional classes. Number 33<br />

is a typical property, a gracious family<br />

home on four floors. The cost to<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> was £200 per year with the<br />

option of purchasing a 65-year ground<br />

lease for £2000. It played a most<br />

important part in his life and he<br />

owned it for seven years. It was to<br />

Eccleston Square that he returned in<br />

the evening of 3 January 1911 after<br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 6<br />

Quotation of the Season<br />

ll these schemes and crimes...are<br />

“A bringing upon him and upon all<br />

who belong to his system a retribution<br />

which many of us will live to see. The<br />

story is not yet finished, but it will not be<br />

so long. We are on his track, and so are<br />

our friends across the Atlantic Ocean....<br />

If he cannot destroy us, we will surely<br />

destroy him and all his gang, and all their<br />

works. Therefore, have hope and faith, for<br />

all will come right.”<br />

—WSC, BROADCAST TO THE FRENCH PEOPLE,<br />

LONDON, 21 OCTOBER 1940<br />

personally observing the famous Siege<br />

of Sidney Street (last issue, page 34)<br />

in his capacity as Home Secretary.<br />

“From early 1913 the house<br />

was leased to the Foreign Secretary,<br />

Sir Edward Grey, when the<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>s moved to the First Lord of<br />

the Admiralty’s official residence at<br />

Admiralty House. They returned to<br />

the Square in late 1916 and finally<br />

disposed of the lease in late May<br />

1918—rather surprisingly to the<br />

Labour Party, who wanted it as<br />

offices and paid <strong>Churchill</strong> £2350 for<br />

the lease and £50 for his carpets.”<br />

The escape of 33 Eccleston<br />

Square leaves 2 Sussex Square as the<br />

only one of <strong>Churchill</strong>'s former homes<br />

to have been destroyed. It was<br />

damaged beyond repair in an air raid<br />

on the night of 9 March 1941.<br />

PRAETORIAN GUARDS<br />

LONDON, APRIL 1ST— Prime Minister<br />

David Cameron has started to keep<br />

tabs on backbench Tory MPs by<br />

joining them for roast beef in the<br />

House of Commons Members’<br />

Dining Room every Wednesday<br />

lunchtime. But the schmoozing has<br />

its limits, reports the Daily Mail:<br />

“When voluble troublemakers such as<br />

Bill Cash or [Sir <strong>Winston</strong>’s grandson]<br />

Nicholas Soames loom, a praetorian<br />

guard of young Cameroons forms a<br />

circle around the PM so he can<br />

munch his Yorkshire in peace.”

Nelson Peltz, Jeffrey Immelt, Rabbi<br />

Marvin Hier and Larry Misel with award.<br />

WIESENTHAL HONORS<br />

NEW YORK, MARCH 30TH— The awards that<br />

pursued Sir <strong>Winston</strong> during his lifetime<br />

continue. Tonight about 500<br />

supporters of the Simon Wiesenthal<br />

Center presented the Center’s Medal of<br />

Valor posthumously to Sir <strong>Winston</strong><br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>, Hiram Bingham IV and<br />

Pope John Paul II. The Humanitarian<br />

Award was given to General Electric<br />

chairman and CEO Jeffrey Immelt.<br />

At a pre-dinner reception at the<br />

Mandarin Oriental hotel, <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Centre chairman Laurence Geller<br />

accepted the medal on behalf of the<br />

late Prime Minister: “Accepting an<br />

award on behalf of <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

can only make me feel like a midget.”<br />

Accepting on behalf of the late<br />

Pope, Archbishop Pietro Sambi, Papal<br />

Nuncio to the United States, said, “I<br />

feel a little bit at home when I am<br />

among Jews. I know their history, their<br />

beliefs and their hopes for the future.<br />

They have given humanity the idea for<br />

a spiritual God which has elevated the<br />

human spirit.” “What about their<br />

bagels” a reporter asked. “Well,” he<br />

said, “As a good Italian, I always prefer<br />

Italian food.”<br />

Robert Bingham accepted the<br />

award for his father, a U.S. diplomat<br />

who enabled more than 2500 Jews to<br />

escape the Holocaust. He attended<br />

with his wife, sister and brother-in-law,<br />

all wearing Hiram Bingham pins.“My<br />

father placed humanity above career,”<br />

he said. “He believed that there was<br />

that of the divinity in every human<br />

being. And he left us a lesson, and that<br />

is to stand up to evil.”<br />

—LIZZIE SIMON, WALL STREET JOURNAL;<br />

FULL ARTICLE: HTTP://ON.WSJ.COM/FFROZI<br />

A PORNY ISSUE<br />

NEW YORK, APRIL 26TH— Another faux<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> “quote” cropped up on the<br />

blog of columnist Jonah Goldberg,<br />

writing about “A Thorny Porn-y Issue”<br />

(http://bit.ly/j7RZ7t). For collectors of<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>ian red herrings, here’s the<br />

alleged exchange:<br />

WSC reportedly says to a woman<br />

at a party, “Madam, would you sleep<br />

with me for £5 million” The woman<br />

stammers: “My goodness, Mr.<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>. Well, yes, I suppose.…”<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> interrupts: “Would you sleep<br />

with me for £5” “Of course not! What<br />

kind of woman do you think I am”<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> replies: “We’ve already established<br />

that. Now we are haggling about<br />

the price.” Cute, but no cigar.<br />

Like the equally fictitious<br />

encounter with Nancy Astor (“If I were<br />

married to you, I’d put poison in your<br />

coffee”…“If I were married to you, I’d<br />

drink it”—actually between Astor and<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>’s friend F.E. Smith, who was<br />

much faster off the cuff—this putdown<br />

cannot be found in <strong>Churchill</strong>’s<br />

canon or memoirs by his colleagues<br />

and family. This hasn’t prevented it<br />

working its way into spurious quotation<br />

books, and, of course, the Web.<br />

Sir <strong>Winston</strong> usually treated<br />

women with Victorian gallantry. He was<br />

so dazzled by Vivien Leigh, star of Gone<br />

with the Wind, that he became uncharacteristically<br />

tongue-tied. When he met<br />

actress Merle Oberon on a beach in the<br />

South of France after WW2, he turned<br />

somersaults in the water. Prurient jests<br />

were not in his make-up.<br />

GETTING THE BOOT<br />

LONDON, APRIL 2ND— It’s been a hallowed<br />

custom for years, but now MPs have<br />

been ordered to stop rubbing the foot<br />

of the imposing bronze statue of<br />

<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> as they enter the<br />

Commons Chamber. It<br />

wore a hole in the great<br />

man’s left foot. It has<br />

now been restored and a<br />

strict instruction has<br />

gone out to MPs to<br />

keep off.<br />

—DAILY MAIL; FULL<br />

ARTICLE AT<br />

http://bit.ly/lsw1it.<br />

TERRY McGARRY<br />

ENCINO, CALIF., APRIL 26TH— Terry<br />

McGarry, 72, died today of a rare brain<br />

disease. A longtime<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>ian, Los<br />

Angeles Times editor<br />

and former UPI<br />

foreign correspondent,<br />

he was a<br />

raconteur extraordinaire,<br />

who loved<br />

nothing better than<br />

traveling cross country to <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

conferences with his wife Marlane on<br />

their BMW motorcycle, only to don<br />

black tie for the formal dinners. The<br />

McGarrys served on the 2001 San<br />

Diego conference committee, a challenging<br />

operation in the wake of 9/11.<br />

Steve Padilla of the Times wrote<br />

that Terry was “one of those old school<br />

journalists who covered just about<br />

everything—wars, the assassination of<br />

President Kennedy, the trial of Jack<br />

Ruby.” Terry was in the room in Dallas<br />

when Ruby shot Kennedy’s killer, Lee<br />

Harvey Oswald.<br />

Terry was a keen follower of<br />

<strong>Finest</strong> <strong>Hour</strong>. His last letter to the<br />

editor commented on the “Some Issues<br />

about Issues” in FH 133: “It needed to<br />

be said and was said quite well.”<br />

“We will also remember that<br />

Terry could make a reader laugh,”<br />

Padilla wrote. He left UPI in 1983<br />

saying that reporting is “like sex: it’s<br />

worth doing well, but sooner or later<br />

you have to stop and eat.” Our sympathies<br />

to Marlane and his family. As<br />

WSC wrote of Joseph Chamberlain:<br />

“One mark of a great man is the power<br />

of making a lasting impression on the<br />

people he meets.” RML<br />

ERRATA, FH 150<br />

Paga 47: At the end of “Dev’s<br />

Dread Disciples,” for “diffuse” read<br />

“defuse.” Thanks for this catch to<br />

Sidney Allinson of Victoria, B.C.<br />

Page 50: Barbara Langworth<br />

wishes to note that her review of My<br />

Years with the <strong>Churchill</strong>s incorrectly<br />

stated that <strong>Churchill</strong>’s 1953 stroke was<br />

omitted (see “Fond Memories,” page<br />

5). It was the editor (as usual) who<br />

misunderstood and added this note to<br />

her text. Sorry. <br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 7

What Is Left of the Special Relationship<br />

RICHARD M. LANGWORTH, EDITOR<br />

When the 2011<br />

London <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

Conference organizers<br />

asked for an issue of <strong>Finest</strong><br />

<strong>Hour</strong> devoted to their<br />

theme, my first reaction was<br />

superficial. What is left of<br />

the Special Relationship for<br />

which <strong>Churchill</strong> strove, at<br />

the expense of British power<br />

and independence, believing<br />

there were greater things at<br />

stake than the Empire<br />

Confined to the area of<br />

foreign relations, not a lot.<br />

Forget the extremists<br />

who say America is the only<br />

country to have gone from<br />

barbarism to decadence<br />

without an intervening period<br />

of civilization; or that Britain<br />

has done nothing for<br />

America except to require<br />

rescue from two cataclysms.<br />

Forget the symbolism of an<br />

American president<br />

returning a <strong>Churchill</strong> bust<br />

loaned to his predecessor—<br />

which in fact was perfectly<br />

understandable (<strong>Finest</strong><br />

<strong>Hour</strong> 142: 7-8).<br />

Forget all that.<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> rejected such<br />

superficial musings in<br />

Virginia in 1946, when<br />

he quoted an English<br />

nobleman, who had said<br />

Britain would have to<br />

become the forty-ninth<br />

state; and an American<br />

editor, who had said the<br />

U.S. might be asked to<br />

rejoin the British Empire. “It<br />

seems to me, and I dare say it<br />

seems to you,” <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

told the Virginia Assembly,<br />

“that the path of wisdom<br />

lies somewhere between<br />

these scarecrow extremes.”<br />

Scarecrow extremes are<br />

one thing, facts another. In<br />

the main, U.S. policy since<br />

the war has been to downplay<br />

the British<br />

connection, or even the<br />

idea that Britain matters:<br />

not only to encourage<br />

the “Winds of Change”<br />

which swept away the<br />

Empire, but the devaluation<br />

of everything from<br />

sterling to British independence<br />

of action.<br />

The recent thrust of<br />

American foreign policy<br />

has been to nudge Britain<br />

into a European federation,<br />

no form of which <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

ever endorsed. Oh, the U.S.<br />

has been quite willing to<br />

count on its “closest friend”<br />

when invading Iraq in 1991,<br />

or Afghanistan ten years<br />

later, or in the operations,<br />

whatever they are, in Libya<br />

at the moment. But reciprocal<br />

support of London by<br />

Washington has been fairly<br />

uncommon.<br />

The only period since<br />

the war when the intergovernmental<br />

Special<br />

Relationship seemed to<br />

resume its wartime inti-<br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 8

PAGE OPPOSITE: Roosevelt and <strong>Churchill</strong> at Casablanca, Morocco,<br />

February 1943; John F. Kennedy and Harold Macmillan aboard the<br />

Presidents yacht Honey Fitz, Washington, April 1961; Ronald Reagan<br />

and Margaret Thatcher at Camp David, December 1984.<br />

macy was when the respective heads of government were<br />

Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher; when America<br />

abandoned traditional anti-colonialism and backed Britain<br />

in the Falklands war. The British Prime Minister repaid that<br />

gesture in August 1990, as Iraq was invading Kuwait, when<br />

she sent her famous message to Reagan’s successor: “George,<br />

this is no time to go wobbly.”<br />

But the Reagan-Thatcher years fade into the blue distance<br />

of the Middle Ages, America reverts to earlier policies, and<br />

the State Department now calls the Falklands the “Malvinas.”<br />

When Prime Minister Gordon Brown visited the White<br />

House in 2009, there was no trip to Camp David, no state<br />

dinner, no joint press conference. In London, an aide to the<br />

U.S. administration thought it right to explain to the Daily<br />

Telegraph: “There’s nothing special about Britain. You’re just<br />

the same as the other 190 countries in the world. You<br />

shouldn’t expect special treatment.”<br />

The President and Prime Minister seemed to improve<br />

the atmosphere in London this May by giving the relationhip<br />

a new name: “Ours is not just a special relationship, it is an<br />

essential relationship.” (“An” or “the” Is it more essential<br />

than others, i.e., special They didn’t elaborate.)<br />

The 2011 <strong>Churchill</strong> Conference has able critics to<br />

document the one-sided Special Relationship between governments.<br />

Piers Brendon’s Decline and Fall of the British<br />

Empire tracks the end of a domain that once spanned a<br />

quarter of the world, a process welcomed by Washington.<br />

Our main argument with John Charmley, years ago (FH<br />

79-81-82-83), was over a very brief section of his <strong>Churchill</strong>:<br />

The End of Glory, suggesting that Britain should have<br />

backed away from the Hitler war. His sequel, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s<br />

Grand Alliance, on Washington’s postwar effort to dismantle<br />

British power, drew few quibbles from us. Confined<br />

only to inter-government relations, we would come not to<br />

praise the Special Relationship, but to bury it.<br />

Is it dead then<br />

No.<br />

Times change. Presidents and Prime Ministers come and<br />

go. None can change the fundamentals, observed by<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> at Harvard in 1943: “Law, language, literature—<br />

these are considerable factors. Common conceptions of<br />

what is right and decent, a marked regard for fair play, especially<br />

to the weak and poor, a stern sentiment of impartial<br />

justice, and above all the love of personal freedom, or as<br />

Kipling put it: ‘Leave to live by no man’s leave underneath<br />

the law’—these are common conceptions on both sides of<br />

the ocean among the English-speaking peoples.”<br />

Perhaps there is less love of personal freedom, as Mark<br />

Steyn argues: “A gargantuan bureaucratized parochialism<br />

leavened by litigiousness and political correctness is a scale<br />

of decline no developed nation has yet attempted.” But if<br />

that is so, the decline is equally precipitous.<br />

By circumstance of history—more than through any specific<br />

actions of <strong>Churchill</strong> or Attlee, Roosevelt or<br />

Truman—international leadership after the war passed to<br />

the United States. As Raymond Seitz asserts herein, the<br />

world (though it doesn’t always accept it) “is incapable of<br />

serious action without the American catalyst.” This changes<br />

nothing about the congruence of heritage, culture, politics<br />

and commerce central to America and Britain.<br />

You see this congruence in all manner of public policy,<br />

Ambassador Seitz writes, “from welfare reform to school<br />

reform, and from zero-tolerance policing to pension management…in<br />

every scholarly pursuit from archaeology to<br />

zoology, in every field of science and research, and in every<br />

social movement from environmentalism to feminism. You<br />

see it in financial regulation and corporate governance…at<br />

every point along the cultural spectrum…You see it in the<br />

big statistics of trade and investment.” And you see it—if<br />

we may digress to our own sphere—in the combination of<br />

British and American expertise that is developing the<br />

massive <strong>Churchill</strong> Archives into an unprecedented tool for<br />

researching Sir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>’s life and times.<br />

The real Special Relationship remains. “The United<br />

States and United Kingdom influence each other’s intellectual<br />

development like no other two countries,” Seitz adds.<br />

“And it is here, I suspect—where the old truth lies—that we<br />

will discover answers about our joint future in a changing,<br />

global world.”<br />

A thing to be avoided at the coming Conference is<br />

concentrating exclusively, or even too deeply, on the relationships<br />

between British and American governments.<br />

There is much more to the Special Relationship than that.<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> saw this in the early 1900s. We see it still in the<br />

early 2000s. We would be fools to ignore it.<br />

Many of these affinities <strong>Churchill</strong> limned long ago at<br />

Harvard, telling his American audience that it would find in<br />

Britain “good comrades to whom you are united by other<br />

ties besides those of State policy and public need.” Seven<br />

decades on, no <strong>Churchill</strong>ian with experience on both sides<br />

of the Atlantic would gainsay him. <br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 9

T H E S P E C I A L R E L A T I O N S H I P<br />

The Power of Words and Machines<br />

In the 21st century <strong>Churchill</strong>s hope, as expressed at Harvard in 1943 and at M.I.T. in 1949,<br />

has the potential to be realized by technology he never knew, but knew would come.<br />

A L L E N<br />

P A C K W O O D<br />

________________________________________________________<br />

Mr. Packwood is Director of the <strong>Churchill</strong> Archives Centre, Cambridge<br />

and Executive Director of The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre United Kingdom. A<br />

longtime contributor to <strong>Finest</strong> <strong>Hour</strong>, he is chairman of the October<br />

2011 International <strong>Churchill</strong> Conference in London.<br />

CHURCHILL AT 33: Already the author of nine books, <strong>Churchill</strong> was<br />

soon to hold his first Cabinet position, President of the Board of Trade,<br />

when he addressed the Authors Club in February 1908. He spoke of<br />

the freedom and power of the pen—or today perhaps the keyboard.<br />

Sir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> is justly celebrated as a master of<br />

the written and spoken word. His own career was<br />

launched and sustained by his pen, which gave him an<br />

incredible freedom and power. As early as 17 February<br />

1908, addressing the Author’s Club of London, he chose to<br />

emphasise the freedom of the writer: “He is the sovereign of<br />

an Empire, self-supporting, self contained. No-one can<br />

sequestrate his estates. No-one can deprive him of his stock<br />

in trade; no-one can force him to exercise his faculty against<br />

his will; no-one can prevent him exercising it as he chooses.<br />

The pen is the great liberator of men and nations.”<br />

What is generally less well known is that he was also<br />

passionate about the potential of science and technology.<br />

He lived in an age of great technological change, and he<br />

embraced it. As a young man, he not only learnt to drive,<br />

but even took flying lessons, taking to the cockpit at a time<br />

when to do so was both pioneering and dangerous. In his<br />

early political life he helped to develop the Royal Naval Air<br />

Service, pushed through the modernisation of the British<br />

Fleet and its conversion from coal to oil, and sponsored<br />

research into the land battleships that would become the<br />

tank. Once convinced of the value of a particular project, he<br />

would often assume the role of its most passionate advocate.<br />

On 31 March 1949, he spoke at the Massachusetts<br />

Institute of Technology on “The 20th Century: Its Promise<br />

and Its Realization.” The theme of his speech was the contrast<br />

between the promise of scientific discoveries and the<br />

terrible weapons and wars they had actually delivered. Yet<br />

even after the carnage of two world wars, and when faced<br />

with the horrors of atomic annihilation, he refused to be<br />

too pessimistic, seeing science as the servant of man rather<br />

than man as the servant of science, and advocating stronger<br />

Anglo-American relations within the new United Nations as<br />

the best way of securing the benefits of scientific progress<br />

and guaranteeing peace.<br />

He predicted that the Soviet regime would be unable<br />

to sustain its grip on its people forever, and that while<br />

“Science no doubt could if sufficiently perverted exterminate<br />

us all,…it is not in the power of material forces in any<br />

period which the youngest here tonight may take into prac-<br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 10

tical account, to alter the main elements in human nature<br />

or restrict the infinite variety of forms in which the soul and<br />

the genius of the human race can and will express itself.”<br />

This was a message of hope, a statement of belief in the<br />

possibility of progress through technological advance.<br />

We cannot presume to know how <strong>Churchill</strong> would<br />

respond to the world today, but we can be confident that he<br />

would want his words to be heard, and the lessons of his era<br />

to be studied, and that he would look to new technology as<br />

a means of reaching the widest possible audience. This after<br />

all is the man who said, upon accepting his Honorary<br />

Degree at Harvard University in September 1943: “It would<br />

certainly be a grand convenience for us all to be able to<br />

move freely about the world—as we shall be able to move<br />

more freely than ever before as the science of the world<br />

develops…and be able to find everywhere a medium, albeit<br />

primitive, of intercourse and understanding.”<br />

It is interesting to note that at the beginning of the<br />

21st century, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s hope has the potential to be<br />

realised through the development of the Internet, which<br />

uses English as its main language and allows truly global<br />

communications. I am not crediting <strong>Churchill</strong> with foreseeing<br />

the World Wide Web, but he did end this section of<br />

his Harvard speech with the observation that “the empires<br />

of the future are the empires of the mind.”<br />

The challenge facing The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre, and the<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> museums, archives and foundations with which it<br />

works, is to harness new technology to ensure that<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>’s words and actions are presented to the next generation<br />

in a form relevant to them. There will always be a<br />

place for conferences and lectures, for the cut and thrust of<br />

debate; there will always be magic in seeing treasures like<br />

the final page of the “finest hour” speech; the actual sheet<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> had in his hand in the House of Commons on 18<br />

June 1940, annotated with his own last-minute changes. Yet<br />

now there is also the ability to capture and present such<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> exhibitions, events and resources to a huge potential<br />

audience, over a longer timescale, using the Internet.<br />

To do this properly will not be cheap or easy. It will<br />

require professional partnerships, with educators who know<br />

how to tailor and present the content for use by students,<br />

and with digital designers and publishers who know how to<br />

develop and present on-line resources. It will require networking,<br />

branding, marketing, publicity and constant<br />

innovation to make sure that the right <strong>Churchill</strong> sites are<br />

accessible and visible, and able to act as beacons in a jungle<br />

of information. But we should take our lead from Sir<br />

<strong>Winston</strong>, the Victorian cavalry officer who embraced new<br />

technology, and like him we should use the power of both<br />

words and machines. <br />

“The outstanding feature of the 20th century has been the enormous expansion in<br />

the numbers who are given the opportunity to share in the larger and more varied life<br />

which in previous periods was reserved for the few and<br />

for the very few. This process must continue at an<br />

increasing rate....Scientists should never underrate the<br />

deep-seated qualities of human nature and how,<br />

repressed in one direction, they will certainly break out<br />

in another. The genus homo—if I may display my<br />

Latin...remains as Pope described him 200 years ago:<br />

Placed on this Isthmus of a middle State,<br />

A being darkly wise and rudely great,<br />

Created half to rise and half to fall;<br />

Great Lord of all things, yet a prey to all;<br />

Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurled;<br />

The glory, jest and riddle of the world.”<br />

—WSC, MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY,<br />

BOSTON, 31 MARCH 1949<br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 11

T H E S P E C I A L R E L A T I O N S H I P<br />

Why Study <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

The American Alliance, for One Thing<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>s modernity of thought, originality, humanity, constructiveness and foresight find<br />

no better expression than in his lifelong quest for close relations with the United States.<br />

M A R T I N G I L B E R T<br />

study <strong>Churchill</strong>” I am often asked.<br />

“Surely he has nothing to say to us today”<br />

“Why<br />

Yet in my own work, as I open file after file<br />

of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s archive, from his entry into Government in<br />

1905 to his retirement in 1955 (a fifty-year span), and my<br />

present focus on completing the 1942 <strong>Churchill</strong> War Papers<br />

volume, I am continually surprised by the truth of his assertions,<br />

the modernity of<br />

his thought, the originality<br />

of his mind, the<br />

constructiveness of his<br />

proposals, his<br />

humanity, and, most<br />

remarkable of all, his<br />

foresight.<br />

Nothing was<br />

more central to<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong>’s view of the<br />

world than the importance<br />

of the closest<br />

possible relations with<br />

the United States. “I<br />

delight in my<br />

American ancestry,” he<br />

once said. Not just his<br />

American mother, but<br />

his personal experiences<br />

in traveling<br />

through the United<br />

States, starting in 1895<br />

when he was just twenty-one, gave him a remarkable sense<br />

of American strength and potential.<br />

On 13 May 1901, when Britain and the United States<br />

were on a collision course over the Venezuela-British Guiana<br />

boundary, <strong>Churchill</strong> told the House of Commons, in only<br />

the third time he had spoken there: “Evil would be the<br />

counselors, dark would be the day when we embarked on<br />

Chris check<br />

FH122 files for<br />

high-def .jpg<br />

that most foolish, futile and fatal of all wars—a war with<br />

the United States.”<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> held his last Cabinet fifty-four years later,<br />

on 5 April 1955. In his farewell remarks to his Ministers, he<br />

said: “Never be separated from the Americans.” For him,<br />

Anglo-American friendship and cooperation, of the closest<br />

sort, was the cornerstone of the survival, political, economic<br />

and moral, of the<br />

Western World.<br />

Although<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> was never<br />

blind to American<br />

weaknesses and mistakes<br />

with regard to the<br />

wider world, his faith<br />

was strong that when<br />

the call came, as it did<br />

twice in his lifetime,<br />

for America to come to<br />

the rescue of western<br />

values and indeed of<br />

western civilisation, it<br />

would do so, whatever<br />

the initial hesitations.<br />

His foresight<br />

covered every aspect of<br />

our lives, both at home<br />

and abroad. He was<br />

convinced that man<br />

had the power—once<br />

he acquired the will—to combat and uproot all the evils<br />

that raged around him, whether it was the evils of poverty<br />

or the evils of mutual destruction. “What vile and utter<br />

folly and barbarism it all is”—such was his verdict on war.<br />

Once a war had been thrust on any nation, <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

was a leading advocate of fighting it until it was won, until<br />

the danger of subjugation and tyranny had been brought to<br />

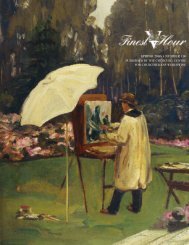

CHRISTMAS 1944: Several Canadian firms commissioned this calendar artwork,<br />

which appeared in color on the cover of <strong>Finest</strong> <strong>Hour</strong> 122, Spring 2004.<br />

________________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

The Rt. Hon. Sir Martin Gilbert CBE, the official biographer of Sir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> since 1968, has published<br />

almost as many words on his subject as <strong>Churchill</strong> wrote, and has honored <strong>Finest</strong> <strong>Hour</strong> with his contributions for nearly thirty<br />

years. This article, first published in FH 60 in 1988, has been revised and expanded in accord with the theme of this issue.<br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 12

an end. He was equally certain that, by foresight and<br />

wisdom, wars could be averted: provided threatened states<br />

banded together and built up their collective strength. This<br />

is what he was convinced that the Western world had failed<br />

to do in the Baldwin-Chamberlain era, from 1933 to 1939.<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> always regarded the Second World War as<br />

what he called the “unnecessary war,” which could in his<br />

view have been averted by the united stand of those endangered<br />

by a tyrannical system. Forty years later, in the Cold<br />

War, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s precept was followed. The result is that the<br />

prospects for a peaceful world were much enhanced.<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> also believed in what he called (in 1919)<br />

“the harmonious disposition of the world among its<br />

peoples.” This recognition of the rights of nationalities and<br />

minorities is something that, even now, the leading nations<br />

are addressing. One of his hopes (1921) was for a Kurdish<br />

National Home, to protect the Kurds from any future threat<br />

in Baghdad. In 1991 and again in 2003, Britain, along with<br />

the United States, took up arms against that threat; and in<br />

2011 the two countries are a leading part of the coalition to<br />

protect the people of Libya from another tyrant.<br />

Democracy was <strong>Churchill</strong>’s friend; tyranny was his<br />

foe. When, in 1919, he called the Bolshevik leader Lenin<br />

the “embodiment of evil,” many people thought it was a<br />

typical <strong>Churchill</strong> exaggeration. “How unfair,” they<br />

exclaimed, “how unworthy of a statesman.” While I was in<br />

Kiev in 1991, I watched the scaffolding go up around<br />

Lenin’s statue. The icon of seventy years of Communist rule<br />

was about to be dismantled, his life’s work denounced as<br />

evil by the very people who had been its sponsors, and its<br />

victims. They knew that <strong>Churchill</strong> had been right from the<br />

outset: Lenin was evil, and his system was a cruel denial of<br />

individual liberty.<br />

From the first days of Communist rule in Russia,<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> did not doubt for a moment that the Communist<br />

system would be a blight on free enterprise and a terrible<br />

restraint on all personal freedoms. Yet when he warned the<br />

American people in 1946, in a speech at Fulton, Missouri,<br />

that an “Iron Curtain” had descended across Europe,<br />

cutting off nine former independent States from freedom,<br />

he was denounced as a mischief-maker.<br />

Whatever Britain’s dispute or disagreement with the<br />

United States might be, <strong>Churchill</strong> was firm in refusing to<br />

allow Anglo-American relations to be neglected. In 1932 he<br />

told an American audience, in words that he was to repeat<br />

in spirit throughout the next quarter of a century: “Let our<br />

common tongue, our common basic law, our joint heritage<br />

of literature and ideals, the red tie of kinship, become the<br />

sponge of obliteration of all the unpleasantness of the past.”<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> was always an optimist with regard to<br />

human affairs. One of his favourite phrases, a Boer saying<br />

that he had heard in South Africa in 1899, was: “All will<br />

come right.” He was convinced, even during the Stalinist<br />

repressions in Russia, that Communism could not survive.<br />

Throughout his life he had faith in the power of all peoples<br />

to control and improve their own destiny, without the interference<br />

of outside forces. This faith was expressed most<br />

far-sightedly in 1950, at the height of the Cold War, when<br />

Communist regimes were denying basic human rights to<br />

the people of nine capital cities: Warsaw, Prague, Vilnius,<br />

Riga, Tallinn, Budapest, Bucharest, Sofia and East Berlin.<br />

At that time of maximum repression, at the height of<br />

the Stalin era, these were <strong>Churchill</strong>’s words, in Boston:<br />

“The machinery of propaganda may pack their minds with<br />

falsehood and deny them truth for many generations of<br />

time, but the soul of man thus held in trance, or frozen in a<br />

long night, can be awakened by a spark coming from God<br />

knows where, and in a moment the whole structure of lies<br />

and oppression is on trial for its life.”<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> went on to tell his audience: “Captive<br />

peoples need never despair.” Today the captive peoples of<br />

Eastern Europe have emerged from their long night. The<br />

Berlin Wall has been torn down. Tyrants have been swept<br />

aside. The once-dominant Communist Party is now an<br />

illegal organisation throughout much of what used to be the<br />

Soviet empire.<br />

In every sphere of human endeavour, <strong>Churchill</strong> foresaw<br />

the dangers and potential for evil to triumph. Those<br />

dangers are widespread in the world today. He also<br />

pointed the way forward to the solutions for tomorrow.<br />

That is one reason why his life is worthy of our attention.<br />

Some writers portray him as a figure of the past, an<br />

anachronism with out-of-date opinions. In portraying him<br />

thus, it is they who are the losers, for <strong>Churchill</strong> was a man<br />

of quality: a good guide for our troubled decade, and for<br />

the generation now reaching adulthood.<br />

One of the most important and relevant lessons that<br />

we can learn from <strong>Churchill</strong> today is, I believe, the importance<br />

of our democracies and democratic values, something<br />

that we in the West often take for granted. On 8 December<br />

1944, when the Communist Greeks were attempting to<br />

seize power in Athens, <strong>Churchill</strong> told the House of<br />

Commons: “Democracy is no harlot to be picked up in the<br />

street by a man with a Tommy gun. I trust the people, the<br />

mass of the people, in almost any country, but I like to<br />

make sure that it is the people and not a gang of bandits<br />

from the mountains or from the countryside who think that<br />

by violence they can overturn constituted authority, in some<br />

cases ancient Parliaments, Governments and States.”<br />

I would like to end with the seven questions <strong>Churchill</strong><br />

first asked publicly in August 1944, when he was in Italy,<br />

watching the former Fascist country grappling with the<br />

challenges of creating a new government and framework for<br />

its laws and constitution. <strong>Churchill</strong> set out seven questions<br />

to the Italian people that they “should answer,” in his<br />

words, “if they wanted to know whether they had replaced<br />

fascism by freedom.” The questions were: >><br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 13

WHY STUDY CHURCHILL...<br />

“Is there the right to free expression of opinion and of<br />

opposition and criticism of the Government of the day<br />

“Have the people the right to turn out a Government<br />

of which they disapprove, and are constitutional means provided<br />

by which they can make their will apparent<br />

“Are their courts of justice free from violence by the<br />

Executive and from threats of mob violence, and free from<br />

all association with particular political parties<br />

“Will these courts administer open and well-established<br />

laws, which are associated in the human mind with<br />

the broad principles of decency and justice<br />

“Will there be fair play for poor as well as for rich, for<br />

private persons as well as for Government officials<br />

“Will the rights of the individual, subject to his duties<br />

to the State, be maintained and asserted and exalted<br />

“Is the ordinary peasant or workman, who is earning a<br />

living by daily toil and striving to bring up a family, free<br />

from the fear that some grim police organization under the<br />

control of a single Party, like the Gestapo, started by the<br />

Nazi and Fascist parties, will tap him on the shoulder and<br />

pack him off without fair or open trial to bondage or illtreatment<br />

“These simple, practical tests,” he added, “are some of<br />

the title deeds on which a new Italy could be founded.”<br />

After the war, <strong>Churchill</strong> was to repeat these same<br />

seven questions whenever he was asked on what freedom<br />

should be based, and on how a truly free society could be<br />

recognised. They are questions that we should learn by<br />

heart, and ask of each country that struggles to build<br />

freedom. In an ideal world, they are questions that every<br />

Member State of the United Nations should be able to<br />

answer in the affirmative. It is for the generation entering<br />

into adulthood today to try to make that happen. <br />

W I T A N D W I S D O M<br />

Reflections on America<br />

<strong>Churchill</strong> never criticized America publicly. Asked in<br />

1944 if he had any complaints he replied, “Toilet<br />

paper too thin, newspapers too fat.” With close associates<br />

he was less reticent, yet he always maintained a decent<br />

respect for the motherland which claimed him as a son.<br />

His prescription for a fraternal relationship “between<br />

the two great English-speaking organizations” was regularly<br />

expressed, and he never lost faith in America’s destiny or<br />

capacity for good. His greatest disappointment in old age,<br />

one of his closest colleagues confided, was that the “special<br />

relationship” never blossomed as he had wished. Surely he<br />

would be cheered by the recent Anglo-American collaborations—and<br />

those of the broader “Anglosphere” with<br />

Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and, in the 21st century,<br />

India as well.<br />

Robert Pilpel, writing in <strong>Finest</strong> <strong>Hour</strong>, expressed the<br />

belief that <strong>Churchill</strong>’s American affinity began the day he<br />

first arrived in New York in 1895: “…a life which before<br />

1895 seemed destined to yield a narrow range of skimpy<br />

achievements became from 1895 onwards a life of glorious<br />

epitomes and stunning vindications. Credit Bourke<br />

Cockran, New York’s overflowing hospitality, the railroad<br />

journey to Tampa and back, or the rampant vitality of a<br />

nation outgrowing itself day by day. Credit whatever you<br />

will, but do not doubt that <strong>Winston</strong>’s exposure to his<br />

mother’s homeland struck a spark in his spirit. And it was<br />

this spark that illuminated the long and arduous road that<br />

would take him through triumphs and tragedies to his rendezvous<br />

with greatness.”<br />

This is a very great<br />

country my dear<br />

Jack. Not pretty or<br />

romantic but great<br />

and utilitarian. There<br />

seems to be no such<br />

thing as reverence or<br />

tradition. Everything<br />

is eminently practical and things are judged from a matter<br />

of fact standpoint. (1895)<br />

<br />

I have always thought that it ought to be the main end<br />

of English statecraft over a long period of years to cultivate<br />

good relations with the United States. (1903)<br />

<br />

England and America are divided by a great ocean of<br />

salt water, but united by an eternal bathtub of soap and<br />

water. (1903)<br />

<br />

Deep in the hearts of the people of these islands…lay<br />

the desire to be truly reconciled before all men and all<br />

history with their kindred across the Atlantic Ocean, to blot<br />

out the reproaches and redeem the blunders of a bygone<br />

age, to dwell once more in spirit with them, to stand once<br />

more in battle at their side, to create once more a union of<br />

hearts, to write once more a history in common. (1918)<br />

<br />

I felt a strong feeling of sentiment when I saw...that the<br />

Coldstream Guards and the United States Marines were<br />

standing side by side. It looked to me as if once again the<br />

great unconquerable forces of progressive and scientific civilization<br />

were recognizing all they had in common and all<br />

they would have to face in common. (1927)<br />

FINEST HOUR 151 / 14

We have slipped off<br />

the ledge of the precipice<br />

and are at bottom. The<br />

only thing now is not to<br />

kick each other while we<br />

are there. (1932)<br />

<br />

I wish to be Prime<br />

Minister and in close and<br />