BRIGADE INSIGHT - Brigade Group

BRIGADE INSIGHT - Brigade Group

BRIGADE INSIGHT - Brigade Group

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

22<br />

SNIPPETS<br />

The plague in Indore<br />

Geddes came to Indore as an advisor when the<br />

city was stricken with the plague. He trampled<br />

through crowded lanes and dirty river banks,<br />

marking on a map places that posed the most<br />

serious threats to public health. The sight of<br />

any white man with a map left local people<br />

fearful of what demolition may be ordered in<br />

the interests of plague control. But the sight<br />

of Geddes seemed to leave them positively<br />

terrified. Geddes asked his Indian assistant<br />

why people shrank from him in such horror.<br />

After much diplomatic evasion, his assistant<br />

finally revealed that they thought Geddes to<br />

be “the old Sahib that brings the plague”.<br />

That very afternoon Geddes went to the<br />

Home Minister of the ruling prince of Indore<br />

and, after explaining the problem, asked to<br />

be made ‘Maharaja for a Day’. Given the dire<br />

situation, consent was granted and Geddes<br />

went on to enlist the enthusiastic support of<br />

Indore’s mayor, “an able Brahmin doctor”.<br />

An imaginative campaign<br />

Geddes proceeded to launch an imaginative<br />

campaign. News was spread throughout the<br />

city that a new kind of pageant would be held<br />

on Deepavali day. The grand festival procession,<br />

the biggest feature of the celebration,<br />

would not follow the old route through the<br />

city. Instead, it would travel only along streets<br />

where houses had been cleaned or repaired.<br />

A Hindu priest and a Mullah were enlisted to<br />

lead clean up efforts, repair streets outside<br />

temples and mosques and plant trees. Free<br />

removal of rubbish was advertised. In the six<br />

weeks prior to the great day, over 6000 loads<br />

of rubbish were carted away from homes and<br />

courtyards (“with much inconvenience to the<br />

rats formerly housed therein”). Plague spreading<br />

rats were trapped by the thousands. A<br />

wave of housecleaning, painting and repairing<br />

swept through the city—after all, everyone<br />

wanted the honour of having the procession<br />

on their street.<br />

The procession<br />

Geddes planned the actual procession with<br />

equal wisdom. When the great day finally<br />

arrived—the day when he was Maharaja—the<br />

procession was magnificent.<br />

First came the procession of the State,<br />

Maharaja for a Day<br />

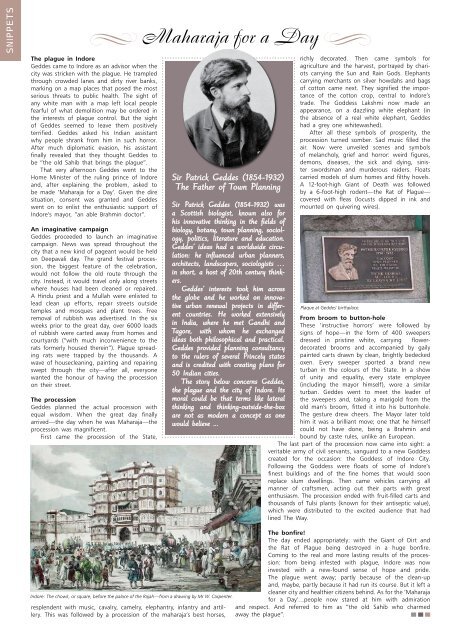

Sir Patrick Geddes (1854-1932)<br />

The Father of Town Planning<br />

Sir Patrick Geddes (1854-1932) was<br />

a Scottish biologist, known also for<br />

his innovative thinking in the fields of<br />

biology, botany, town planning, sociology,<br />

politics, literature and education.<br />

Geddes’ ideas had a worldwide circulation:<br />

he influenced urban planners,<br />

architects, landscapers, sociologists …<br />

in short, a host of 20th century thinkers.<br />

Geddes’ interests took him across<br />

the globe and he worked on innovative<br />

urban renewal projects in different<br />

countries. He worked extensively<br />

in India, where he met Gandhi and<br />

Tagore, with whom he exchanged<br />

ideas both philosophical and practical.<br />

Geddes provided planning consultancy<br />

to the rulers of several Princely states<br />

and is credited with creating plans for<br />

50 Indian cities.<br />

The story below concerns Geddes,<br />

the plague and the city of Indore. Its<br />

moral could be that terms like lateral<br />

thinking and thinking-outside-the-box<br />

are not as modern a concept as one<br />

would believe ...<br />

richly decorated. Then came symbols for<br />

agriculture and the harvest, portrayed by chariots<br />

carrying the Sun and Rain Gods. Elephants<br />

carrying merchants on silver howdahs and bags<br />

of cotton came next. They signified the importance<br />

of the cotton crop, central to Indore’s<br />

trade. The Goddess Lakshmi now made an<br />

appearance, on a dazzling white elephant (in<br />

the absence of a real white elephant, Geddes<br />

had a grey one whitewashed).<br />

After all these symbols of prosperity, the<br />

procession turned somber. Sad music filled the<br />

air. Now were unveiled scenes and symbols<br />

of melancholy, grief and horror: weird figures,<br />

demons, diseases, the sick and dying, sinister<br />

swordsman and murderous raiders. Floats<br />

carried models of slum homes and filthy hovels.<br />

A 12-foot-high Giant of Death was followed<br />

by a 6-foot-high rodent—the Rat of Plague—<br />

covered with fleas (locusts dipped in ink and<br />

mounted on quivering wires).<br />

Plaque at Geddes' birthplace.<br />

From broom to button-hole<br />

These ‘instructive horrors’ were followed by<br />

signs of hope—in the form of 400 sweepers<br />

dressed in pristine white, carrying flowerdecorated<br />

brooms and accompanied by gaily<br />

painted carts drawn by clean, brightly bedecked<br />

oxen. Every sweeper sported a brand new<br />

turban in the colours of the State. In a show<br />

of unity and equality, every state employee<br />

(including the mayor himself), wore a similar<br />

turban. Geddes went to meet the leader of<br />

the sweepers and, taking a marigold from the<br />

old man’s broom, fitted it into his buttonhole.<br />

The gesture drew cheers. The Mayor later told<br />

him it was a brilliant move; one that he himself<br />

could not have done, being a Brahmin and<br />

bound by caste rules, unlike an European.<br />

The last part of the procession now came into sight: a<br />

veritable army of civil servants, vanguard to a new Goddess<br />

created for the occasion: the Goddess of Indore City.<br />

Following the Goddess were floats of some of Indore’s<br />

finest buildings and of the fine homes that would soon<br />

replace slum dwellings. Then came vehicles carrying all<br />

manner of craftsmen, acting out their parts with great<br />

enthusiasm. The procession ended with fruit-filled carts and<br />

thousands of Tulsi plants (known for their antiseptic value),<br />

which were distributed to the excited audience that had<br />

lined The Way.<br />

Indore: The chowk, or square, before the palace of the Rajah—from a drawing by Mr W. Carpenter.<br />

resplendent with music, cavalry, camelry, elephantry, infantry and artillery.<br />

This was followed by a procession of the maharaja’s best horses,<br />

The bonfire!<br />

The day ended appropriately: with the Giant of Dirt and<br />

the Rat of Plague being destroyed in a huge bonfire.<br />

Coming to the real and more lasting results of the procession:<br />

from being infested with plague, Indore was now<br />

invested with a new-found sense of hope and pride.<br />

The plague went away; partly because of the clean-up<br />

and, maybe, partly because it had run its course. But it left a<br />

cleaner city and healthier citizens behind. As for the ‘Maharaja<br />

for a Day’…people now stared at him with admiration<br />

and respect. And referred to him as “the old Sahib who charmed<br />

away the plague”.