one page: brisbane

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

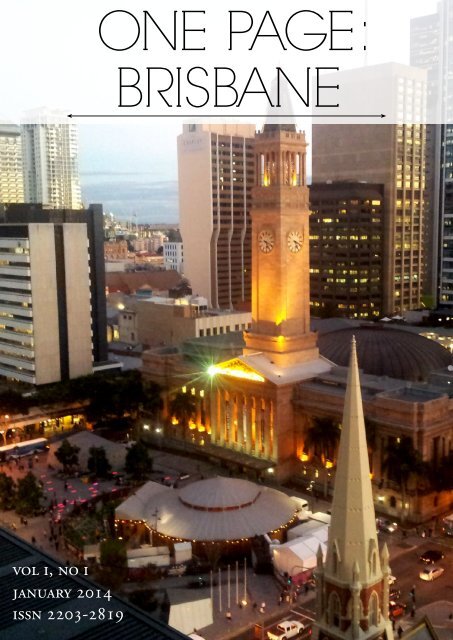

<strong>one</strong> <strong>page</strong>:<br />

<strong>brisbane</strong><br />

vol i, no i<br />

january 2014<br />

issn 2203-2819<br />

1

contents<br />

billy burmester and alyssa miskin<br />

cecile blackmore and david sparkes<br />

david burnett<br />

billy burmester<br />

charlotte nash<br />

matthew wengert<br />

matthew wengert<br />

teagan kumsing<br />

daniel browne<br />

sam banks<br />

matthew wengert<br />

jane etherton<br />

cindy keogh<br />

alyssa miskin<br />

james wright<br />

caitlin morgan<br />

alyssa miskin<br />

daniel browne<br />

ben gordes<br />

patrick begley<br />

donna kleiss<br />

sam banks<br />

dora hawk<br />

3<br />

4<br />

6<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

15<br />

17<br />

19<br />

20<br />

22<br />

23<br />

24<br />

26<br />

27<br />

28<br />

29<br />

31<br />

32<br />

33<br />

34<br />

35<br />

this is <strong>brisbane</strong><br />

from the editors<br />

brunch for 20<br />

food<br />

a board, a bar of wax, and a pair of shorts<br />

non-fiction<br />

the beginning and the end<br />

poetry<br />

the <strong>one</strong> you feed<br />

fiction<br />

the ghosts of german station<br />

fiction<br />

the meaning of meanjin<br />

reflection<br />

crème brûlée in <strong>brisbane</strong><br />

food<br />

payment<br />

fiction<br />

four seasons<br />

fiction<br />

albion flour mill<br />

photography<br />

esperanza<br />

non-fiction<br />

some things you should know / jesus<br />

poetry<br />

the sum of your things<br />

poetry<br />

dark musings<br />

serial fiction<br />

dust bunnies<br />

fiction<br />

grandad’s greenhouse<br />

memoir<br />

lactocracy<br />

fiction<br />

tuning in and bugging out<br />

reflection<br />

artifiical eyes<br />

non-fiction<br />

edge shopping<br />

shopping<br />

the devil you know<br />

profile<br />

lost in hong kong<br />

poetry<br />

the <strong>one</strong> <strong>page</strong> team<br />

image credits<br />

2

this is <strong>brisbane</strong><br />

We’re proud to introduce you to a new monthly magazine that will showcase Brisbane like never before. With One Page:<br />

Brisbane, we want to open Brisbane up to the world by bringing together a collection of thinkers, feelers, readers, writers, and<br />

creators.<br />

Each month, One Page will feature concise and evocative stories, articles, photographs, recipes, reports, poems, and art. Every<br />

story has been shaped by Brisbane: its well-documented climate, its unique culture, and most of all, its people. Above all, we<br />

aim open windows into the city’s life and culture.<br />

For our first issue, we have lots of short stories and poems by emerging Brisbane authors; a photo essay feature on the fire at<br />

the Albion flour mill; interviews with artisans and newcomers in the city; and plenty else besides. The first issue is in the format<br />

you see before you. However, we’re working hard on smartph<strong>one</strong> and tablet apps. Keep your eyes on www.<strong>one</strong><strong>page</strong><strong>brisbane</strong>.<br />

com.au for news and updates.<br />

One Page: Brisbane is always looking for submissions. If you have a story, article, photo series, or artwork that is based in, or<br />

inspired by, Brisbane, send it to submissions@<strong>one</strong><strong>page</strong><strong>brisbane</strong>.com.au.<br />

Enjoy, and welcome home.<br />

Billy Burmester and Alyssa Miskin<br />

Editors-in-chief<br />

contact us<br />

web<br />

www.<strong>one</strong><strong>page</strong><strong>brisbane</strong>.com.au<br />

info<br />

info@<strong>one</strong><strong>page</strong><strong>brisbane</strong>.com.au<br />

subscriptions<br />

subscriptions@<strong>one</strong><strong>page</strong><strong>brisbane</strong>.com.au<br />

submissions<br />

submissions@<strong>one</strong><strong>page</strong><strong>brisbane</strong>.com.au<br />

twitter<br />

@<strong>one</strong><strong>page</strong><strong>brisbane</strong><br />

facebook<br />

<strong>one</strong><strong>page</strong><strong>brisbane</strong><br />

instagram<br />

@<strong>one</strong><strong>page</strong><strong>brisbane</strong><br />

3

unch for 20<br />

cecile blackmore and david sparkes<br />

It’s a Wednesday morning. The barista is steaming milk<br />

with a practiced ease for a couple by the door: his only<br />

customers so far. With any luck, he can duck out for a smoke<br />

when they leave. His hangover is worsening slightly, but it’s<br />

quiet today. This vision of weekday tranquility dissolves,<br />

however, when a lanky young man, sporting a tweed jacket<br />

and Docs despite the stifling heat outside, strolls through the<br />

door, eyes fixed on his half-shattered smartph<strong>one</strong>.<br />

He takes a seat, oddly, at the large wooden table in the<br />

middle of the room. The barista is puzzled, but gives him<br />

a curt nod of acknowledgement as he delivers the couple’s<br />

cappuccinos and looks under the counter for menus.<br />

When he looks up, the guy in the tweed jacket has been<br />

joined by at least seven others, staring about the café and<br />

chattering happily.<br />

“Are you right for coffees, guys” he stammers, daunted by<br />

the prospect of a busy morning.<br />

Tweed Jacket gives him a peaceful smile.<br />

“We’re right for now, thanks,” he says. “We’re waiting on<br />

a few more people.”<br />

Brunch for 20 began quite innocently. At the start of this year,<br />

a few close friends and I enjoyed a late-ish breakfast at the<br />

acclaimed Spring Hill Deli <strong>one</strong> morning, where I encountered<br />

the flawless Eggs Benedict. I suddenly realized how limited my<br />

palate had become, and vowed from then on to expand it—<br />

who knew what else could be out there I scoured the internet<br />

from the dregs of Urbanspoon to the wittiest of breakfast blogs,<br />

sifting through tales of burnt bacon and belligerent baristas to<br />

gather a great list of places to try.<br />

Brunchtime became a weekly event as we wolfed down potted<br />

eggs in Woolloongabba and sipped spiced piccolos in West<br />

End. Before all this, food and a catch-up generally involved<br />

an amiable shuffle to the nearest Grill’d or Coffee Club. The<br />

biggest shake-up to this new pastime, however, occurred in the<br />

form of Facebook’s new event privacy settings – all my friends<br />

could see I was hosting ‘public events’ in the form of intimate<br />

brunches, and they began to express their disappointment at<br />

having been excluded. One thing led to another, and the invite<br />

list to a brunch date is now over 100-strong.<br />

Most cafés we visited manage to tick at least two of the three<br />

main boxes: coffee, food and ambience. Sometimes they only<br />

scraped <strong>one</strong>. Most impressive were the cafés that managed<br />

to display all these things at near-perfection, and, like a good<br />

shepherd, I wanted to get my friends to these places.<br />

Breakfast (or brunch, as we prefer it) has, to some extent,<br />

become the poor student’s gourmet haven. Rather than<br />

nattering over old wine, we wax lyrical over filter coffees and<br />

sweet potato waffles (keep it up, Kettle and Tin). The diverse<br />

collective of tastes means an interesting review by the end.<br />

‘Internet opinions’ are often completely centered on <strong>one</strong><br />

or two people’s opinions of a place, and I like to think that<br />

getting opinions from others makes our pretentious remarks a<br />

little bit more grounded.<br />

We have had some interesting run-ins as we grow in number<br />

and notoriety. We were chased out of a New Farm café, after<br />

overestimating its capacity for hungry brunch-goers. Likewise,<br />

many owners come out and are confused by our numbers,<br />

but are pleasantly surprised when we tell them “there’s no<br />

occasion—we just like brunch.” The lovely ladies of the Five<br />

Sisters Art Café were completely baffled by our appearance,<br />

going as far to make a Facebook status about us. The quiet little<br />

4

joint was not quite prepared for us to completely rearrange<br />

the furniture and take over the entire outside seating area.<br />

Another interesting little café that should not have worked was<br />

Sisco, where we literally took up every seat inside the café,<br />

leaving some outdoor space for any other daring customers.<br />

I sometimes, sometimes, take pity on the poor other diners<br />

present around us as we squawk about brunch in a way that<br />

only twenty people can.<br />

The faces of people strolling past a café on a weekday to see<br />

us in there, having a jolly celebration is just something else—<br />

some sort of combination of fear, amusement, and general<br />

distaste when they realize that breakfast is going be a bit loud<br />

today. While the owners tend to be more than pleased about<br />

our appearance, baristas are another story. We follow a few<br />

simple rules—a creed, if you will—to guide us.<br />

Avoid chains with fervour—variety is the spice of life!<br />

Never make a booking—chaos is part of the game<br />

Avoid weekends—chaos is all well and good, but brunch for<br />

20 on a Sunday morning will likely remain a dream never<br />

to be realised, we’re not sadists<br />

Never look back—there is another café out there waiting to<br />

be pillaged.<br />

This is Brunch for 20. Come and visit us on Facebook for<br />

weekly updates on the chaos and to find some inspiration for<br />

a new morning adventure. s<br />

5

a board,a bar of wax,and<br />

a pair of shorts<br />

david burnett<br />

The long-board or ‘Malibu’ is perhaps the quintessential item<br />

that represents California to me. One of first experiences<br />

of travelling in the United States was driving the glorious<br />

Highway 1 or Pacific Coast Highway from Los Angeles to Santa<br />

Cruz. Surf culture, spectacular scenery, sea fog, and images<br />

of surfers riding the edge of the Pacific were the essence of<br />

that trip so it was Greg Noll’s gorgeous yellow board that<br />

immediately caught my attention in ‘California Design 1930–<br />

1965: Living in a Modern Way’.<br />

Within the culture and honour-roll of surfing, Greg Noll is <strong>one</strong><br />

of its ‘legends’. Born in San Diego, Noll moved with his family<br />

to Manhattan Beach, California at the age of three. He began<br />

to surf at around eleven, joining surf clubs and later, the Los<br />

Angeles County Lifeguards. He was introduced to surfboard<br />

shaping by another legend of the surfing world, Dale Velzy,<br />

who opened a professional surf shop in Manhattan Beach in<br />

1950, and is credited with being the first commercial board<br />

shaper. Noll was part of the United States Lifeguard team who<br />

competed in the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games and had a<br />

considerable impact on the Australian surfing scene.<br />

In 1954, Noll moved to Hawaii, finishing high school and<br />

continuing to surf. He gained notoriety in 1957 as <strong>one</strong> of a<br />

group of surfers who took on big waves at Waimea Bay, Hawaii.<br />

The seasonal wave breaks at Waimea can be anything between<br />

nine to fifteen metres and are still recognised as an important<br />

destination for big wave surfing. A short film on this famous<br />

surf spot is available on Youtube.<br />

The board-shaping skills that Noll learned in California evolved<br />

into his own very successful business in the 1950s at Hermosa<br />

Beach, California. He made a series of short surf films in the<br />

late 1950s before giving up surfing in 1969 after riding what<br />

is reputed to be the largest wave ever ridden at Makaha,<br />

Hawaii. Having secured his reputation as the most fearless<br />

surfer known, he turned to commercial fishing in Alaska. With<br />

a resurgence in longboards in the 1990s, he resumed board<br />

shaping and organising longboard surf events. He continues<br />

to make a limited number of boards and replicas for collectors<br />

from his home in Crescent City, California.<br />

The surf board included in ‘California Design 1930–1965:<br />

Living in a Modern Way’ is representative of this great ‘classic’<br />

6

era of surfing when finding and catching waves and breaks was<br />

all that mattered to a generation of young men for whom jobs,<br />

marriage and mortgages meant little by comparison. As Greg<br />

Noll has said, ‘I’m not sorry for being a fun hog for all of my<br />

life’.<br />

The longboard was the original form for surfboards when they<br />

were first manufactured in the United States in the 1920s.<br />

They evolved from the Polynesian and Hawaiian boards made<br />

of solid wood used in the ancient practice of Hoe he’e nalu, a<br />

kind of stand-up paddle boarding. Construction materials for<br />

longboards evolved from plywood and balsawood through to<br />

fibreglass and polyurethane foam. The longboard or ‘Malibu’,<br />

typically 4 to 6 metres in length, dominated the surf scene up<br />

to the late 1960s and 1970s when short ‘performance’ boards<br />

(made famous by renowned Australian surfer Nat Young)<br />

introduced a revolution in style and board manufacture.<br />

Vintage longboards now attract high prices on the collectors<br />

market and have assumed iconic status in the history of surf<br />

culture.<br />

David Burnett is the Curator of International Art at the<br />

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art.<br />

Greg Noll (b.1937, active Hermosa Beach, near Los Angeles)<br />

Surfboard<br />

c.1960<br />

Polyurethane foam, fibreglass cloth, polyester resin, wood<br />

LACMA, Gift of Matt Jacobson<br />

7

the beginning and the end<br />

billy burmester<br />

auspice<br />

n. a divine or prophetic token; an omen.<br />

A flock of cockatoos is visible from the international space station. A town in the Midwest vanishes from maps and nobody can<br />

recall its name. Neighbourhood dogs congregate around your house and wait quietly, heads bowed. The ph<strong>one</strong> rings late at<br />

night but falls silent as you pick it up. The next morning, you stand at the window and watch a dead bat shake the weeklong<br />

stiffness from its legs and wings. It drops from the wire and flaps away, chopping the sunlight into your eyes like a fan blade.<br />

Your father appears at the front door and calls you a pussy and the blood rushes to your neck and hands, just like old times.<br />

How much more it means than his heedless muttering in a dim ward. You waited him out in there. You sat and watched him<br />

and he did not see you. The sun rose and dazzled you.<br />

as the lightning flashes and the wind rises hot<br />

and fast<br />

we were caught between a levee and a firebreak<br />

we built a barricade out of dead ferns and turbine casings<br />

the water rose to meet the smoke<br />

the city clenched like a jaw<br />

we cracked our fists on the black earth<br />

we cracked our lips in the riverbeds<br />

the fish ate their own tails<br />

the roads crumbled in the sun<br />

we aband<strong>one</strong>d the dams and the windmills<br />

we folded our clothes and crawled back into the sea s<br />

8

the <strong>one</strong> you feed<br />

charlotte nash<br />

Sometimes, betrayals are innocuous things. Your friend tells<br />

your secret when they promised not. You hate them for it, but<br />

real damage is slight, so the elders say. No <strong>one</strong> takes slights<br />

of word seriously here, where a boy is born with two selves.<br />

When every day until the age of fifteen is focussed on refining<br />

the good self and shunning the monstrous self, until that day,<br />

the rite of passage, when the boy enters the stadium and slays<br />

his dark self so the good will become adult.<br />

For Garrick, that day is today. I am nervous. His twin-self<br />

crosses the red dust, far beneath the rising seats. A sheer<br />

wall separates him from the watchers, and above is a ring of<br />

archers. He enters a twin, two boys the same, but only <strong>one</strong> will<br />

leave. And if the monster is the victor, then n<strong>one</strong> will. I could<br />

lose this friend today.<br />

But no <strong>one</strong> thinks the worst will happen; it almost never does.<br />

Boys are trained in how to protect their good selves, how to<br />

nurture them with learning. Their fathers pass the wisdom<br />

of their own battles; those with fathers, at least. I finger the<br />

st<strong>one</strong>s behind my back, wondering if I can still feel regret<br />

about that. I wait, but n<strong>one</strong> comes. No, then. I am cured of it.<br />

Garrick, both of him, makes his bows. No <strong>one</strong> can tell which<br />

is the good self and which is the monster; that will come only<br />

with victory. But I can tell. I know him well.<br />

They each take an edged weapon from their belts, and step<br />

away into the dust, as if they are just to spar. Expectation is<br />

oddly dim here; the crowd almost looks bored. Good, that<br />

is good. They think they know Garrick well. They know he<br />

is the son of the highest elder, the most educated, the most<br />

dedicated. Destined for greatness. This is almost a formality:<br />

his monstrous self should be so weak from neglect that the<br />

battle will be over quickly.<br />

The first blows fall metal on metal. Good-Garrick and monster-<br />

Garrick circle and clash. Dust rises, cloaking their skin, sticking<br />

to sweat. They are soon both red-dust creatures, no skin to be<br />

seen, and only the metal edges glint through the fray. Then,<br />

there is a stumble. One Garrick goes down; the crowd leans<br />

forward. The other Garrick does not hesitate. He drives the<br />

point of the blade through the downed Garrick’s chest. The<br />

downed Garrick jerks around the blade, curled like a spider<br />

on its back, then is still.<br />

My heart fights my breath for space in my throat. My skin drums<br />

with the noise from the stands. The victor Garrick stands<br />

before the applause, a red-skinned version of the Garrick who<br />

walked in. He closes his eyes and raises his palms, salute to the<br />

elders. The archers relax. Then, Garrick retrieves his sword<br />

and strides towards the exit.<br />

No elder moves. They maintain applause, standing now, tears<br />

on some faces. Pride, I believe, for they see the good-Garrick<br />

leave. Passed through the rite, and now to be a man. This is the<br />

great moment for them.<br />

For them.<br />

I do not stay to witness more but descend to the arena level on<br />

the seldom-used stair. Garrick is waiting in the tunnel, and he<br />

brings his eyes up from the dust. We look at each other, with<br />

our black irises reflecting the torchlight. Garrick, so dusty no<br />

<strong>one</strong> can see the evil marks. Me, with the control I learned from<br />

my father, how to use my mind not to show them. Monsters,<br />

both.<br />

This is the great moment.<br />

I offer the eye lenses he will need to stay hidden. Garrick nods<br />

his thanks. He has learned well in all our lessons, proved<br />

himself skilled at concealment, even from his good-self. And<br />

the good-self never realised another could teach his monster<br />

just as well. My pride burns my eyes when he leaves.<br />

Now good-Garrick lies dead in the dust. The elders will be<br />

slack, not bothering to clean the body of the assumed monsterself.<br />

They will not find the unmarred skin.<br />

You see, some betrayals are innocuous, but others are not.<br />

Words can cut as deep as a sword, and bring death when<br />

spoken wrong. The good-Garrick told my secret and so the<br />

monster has his chance. s<br />

9

the ghosts of german station<br />

matthew wengert<br />

10

How Godfrey Meisner lost his legs. August 1865.<br />

We were drinking wine, Adam and I, for more than a day and a<br />

night, before his woman told me to be g<strong>one</strong>. She’d had enough<br />

of our foolish drunk talking, so she sent me on my way home<br />

to my own hut, but I lost my way in the night. The bush in<br />

Australia is not like the big forests at home in Wurttemburg,<br />

and it is not easy to make <strong>one</strong>’s way through in the day. It is<br />

even worse in the dark. I wandered about until I came to a<br />

spot that had been cleared of small trees and long grass. In<br />

the middle of this clearing was a very large tree—this gum tree<br />

as the English call it—that was being fired in order to make it<br />

quick work to fell. It was Karl’s place I was on, so I thought,<br />

and, not wanting to go any more through the bush that night,<br />

I lay down on the ground where the night was made warm<br />

by the tree burning. Thinking that I would find my hut in the<br />

morning after a rest, I quickly fell to sleep. Yet I did not wake,<br />

nor ever again move from where I was lying under the tree.<br />

During the night it fell on me.<br />

You may well wonder at a ghost that does not wander; but that<br />

is me, and here I am. Well, it might be more appropriate to say<br />

this is where we are. For the tree is also a ghost, lying where it<br />

fell: across me. You cannot see me, nor the tree, but here we<br />

are and here we stay, both of us lying together.<br />

You might wonder if that hurt me, a burning tree falling over<br />

my middle, but it did not especially. It was all over quickly,<br />

thank Christ. When the powder flask blew I was already dead,<br />

so there went my legs rolling away from me. Even so it did not<br />

cause too much more pain.<br />

Karl found me. That is, Charles, as he now calls himself. It<br />

must have been very dreadful to look on a pair of legs like<br />

that, and when Karl came closer it was by slow steps with his<br />

eyes fixed upon my broken body... you must understand it<br />

was just the lower part of myself that was in his view at that<br />

moment. I suppose that, if not for my clothes, he may have<br />

mistaken me for a native due to my terrible burns, for what<br />

remained of the upper part of me was blacker than night.<br />

The constable arrived by-and-by, and quickly went away again.<br />

He looked about the place, and kept glancing back to where<br />

I lay. He could not stare at my corpse for long before his eyes<br />

turned away. Karl had the good sense at this time to keep his<br />

distance. After only a few minutes the men went off, and came<br />

back in a little while with Adam.<br />

Poor Adam. It was awful to see his distress. He stopped a few<br />

yards back, then came forward to kneel beside me. His hand<br />

came out, as if to touch me, but there was no skin for him to<br />

feel.<br />

The men went away then returned some time later that day<br />

with a horse and some tools. They labored at freeing my<br />

shattered body from under the tree, using iron bars and a<br />

shovel. Karl and the constable wrapped the bits of me in a<br />

couple of sacks, and a miserably small bundle it was, while<br />

Adam recited something from a prayer book. The anger and<br />

upset of all those men was clear when he told the others that<br />

the pastor could not or would not come to me where I lay,<br />

so I was content with the kind words Adam offered at that<br />

wretched place. He was crying, but he was comforted by Karl<br />

as they took my parts away. I remain here in this damnable<br />

place, with the spirit of the tree that fell over me. Whenever<br />

a person comes by, I try to tell them to mix water with their<br />

wine, and to find rest in their own beds, well clear of burning<br />

trees. Of course, they do not hear me.<br />

I’d give anything for a cup of wine now, but I have nothing to<br />

give, nor ever will again—except for my unheard advice.<br />

The three boys had two rifles—single shot .22s with five or<br />

six bullets for each of them—and three knives, two slingshots,<br />

<strong>one</strong> hatchet, and no permission to be away from their homes.<br />

They knew better than to fire the guns within earshot of the<br />

American army camp. Despite the continued talk that year in<br />

Brisbane of Japanese invasion threats, on this day the boys<br />

were more frightened of being heard by the Yank MPs across<br />

the creek, who would take them home to their parents if they<br />

caught them here.<br />

“Come on with that fire, will you. My sister could do it<br />

better than you,” Barry said to the younger Wilson kid.<br />

“Well, bloody well piss off home and tell yer sister to come<br />

back and do it better than me then.”<br />

Jim Wilson couldn’t understand it. He was so good at building<br />

fires, but every time he set the match into the pile of dry stuff<br />

it’d burn for a few seconds and then puff out. He thought he<br />

heard something like wind, but he couldn’t feel even a faint<br />

breeze. He wasn’t brave enough to admit to his brother and<br />

his brother’s mate that he wanted to go home. s<br />

11

the meaning of meanjin<br />

matthew wengert<br />

Clement Byrne Christesen published the first volume of<br />

Meanjin Papers in Brisbane in late 1940, when he was 29 years<br />

old, and he remained its editor until 1974. This literary journal,<br />

or small magazine, began with a pronounced inclination<br />

towards poetry, but also included prose articles and fiction,<br />

as well as artworks.<br />

The publication moved to the University of Melbourne in<br />

1945, lured away from its hometown by an offer of editorial<br />

support and employment for Clem. An obituary from 2003,<br />

written for the University of Melbourne’s magazine, stated<br />

that Meanjin was launched ‘in the inhospitable Brisbane<br />

climate’. While that indelicate reference may be partly based<br />

on an historical misunderstanding of Brisbane’s position in<br />

the second world war, it is more likely to include a typically<br />

elitist view of Melbourne as being culturally superior to its<br />

smaller northern cousin––which, even if true, it isn’t nice to<br />

constantly point out. And, anyway, it isn’t true.<br />

The earliest editions of Meanjin were limited to 250 copies,<br />

which grew in the later 1940s to 500 copies. Each edition<br />

contained a ‘Note’ that explained the meaning of the<br />

magazine’s title: ‘ “Meanjin” was the aboriginal [sic] word for<br />

“spike,” and was the name given to the finger of land bounded<br />

by the Brisbane River and extending from the city proper<br />

to the Botanic Gardens.’ Thus, in geographical and cultural<br />

terms, this plucky little literary journal can be taken to be<br />

synonymous with Brisbane’s creative heart. While it might<br />

surprise a southern snob, Brisbane has always had a cultural<br />

edge that is clear and sharp, which Meanjin pointed to over<br />

seventy years ago.<br />

Clem Christesen’s quarterly commenced with bold ambitions,<br />

and quickly grew to include a pantheon of Australian writers<br />

whose names resound through our literary legacy––and<br />

it continues to add new writers to its considerable pool of<br />

12<br />

published talent. Already by the end of its second full year of<br />

publication (1943) it was including American and European<br />

writers of renown.<br />

Alongside the writing sat the artworks by formidable painters<br />

and printmakers, including Margaret Preston and Brisbaneborn<br />

Lloyd Rees. Some of the local writers published in<br />

volume two include: Vance Palmer, Douglas Stewart, Judith<br />

Wright, Miles Franklin, Colin Thiele, and Manning Clark.<br />

Some of these were included in an Anthology published by<br />

Melbourne University Press in 2012, as well as: A.D. Hope,<br />

Mary Gilmore, David Malouf, Patrick White, Thomas Keneally,<br />

Thea Astley, and Peter Carey. With the hindsight of such an<br />

illustrious backlist, it is evident that Christesen’s aspirational<br />

intentions were achieved. The following lengthy quote is from<br />

an editorial note in 1943 (around the middle of the war):<br />

MEANJIN Papers is devoted to the continued development<br />

of a strong and virile Australian literature, with all its<br />

significant marks of “difference.” It opens its <strong>page</strong>s to the best<br />

poetry and short prose and literary criticism by Australian<br />

and Allied writers. Here you will find the most recent work<br />

by our leading writers, together with the work of our most<br />

interesting newcomers.<br />

Meanjin has been making literary history since December,<br />

1940. No other Australian literary journal is so broadly<br />

based, has attracted such a diverse cross-section of literary<br />

work, or has reached such a wide audience.<br />

For the Catena Collective––publishers of One Page:<br />

Brisbane––the meaning of Meanjin is that a creative project’s<br />

cultural impact and longevity are not pre-determined by either<br />

budgetary or geographical origins. Well conceived and carefully<br />

nurtured ‘products’ can outlive their humble beginnings, and<br />

Brisbane is a great city in which to plant literary seeds. s

crème brûlée in <strong>brisbane</strong><br />

teagan kumsing<br />

Crème brûlée is not a dessert to share: fights can turn nasty<br />

over who gets to crack the top, and that’s not ideal on a first<br />

date. Whether it’s called crème catalana, burnt cream, or crème<br />

brûlée (depending on which country is claiming ownership),<br />

it is a classic, comforting way to end a meal, start <strong>one</strong>, or even<br />

be <strong>one</strong> all by itself.<br />

Montrachet<br />

224 Given Tce, Paddington<br />

You can’t talk French food without mentioning Montrachet.<br />

The elegance of Montrachet is matched entirely by its crème<br />

brûlée: rich, turn-your-spoon-upside-down thick, and so laden<br />

with vanilla it’s practically polka dot. Classic perfection.<br />

Aquitiane<br />

R2 River Quay, South Bank<br />

Generous portion that is plated to reflect the contemporary<br />

style. Aquitiane’s crème brûlée is served with mandarin<br />

segments and hazelnut biscotti—the mandarin adds freshness<br />

and zest to the already light custard and the biscotti are<br />

perfectly crunchy and sturdy for the dunking. A well-balanced<br />

dish that would suit a first-timer who may not be prepared for<br />

intense creaminess.<br />

Fat noodle<br />

21 Queen St, CBD<br />

Come for Luke Nguyen; come back for the crème brûlée. Fat<br />

Noodle offers Vietnamese influence with Jasmine tea flavour.<br />

The jasmine is fresh enough to compete with the custard, but<br />

it’s the heavenly, floral-but-creamy fragrance that’s the real<br />

pay-off. The soft-set custard is rich and bulging, and served<br />

in just the right portion. The excellent accompaniment to Fat<br />

Noodle’s complimentary jasmine tea.<br />

Willow & Spoon<br />

28 Samford Rd, Alderley<br />

Willow & Spoon were famous for their lavender crème brûlée.<br />

Now they’ve overhauled their menu and they soon will be<br />

famous for their pistachio crème brûlée, served with white<br />

chocolate biscuits. The pistachio is full-flavoured, reminiscent<br />

of finest-quality gelato. The biscuits are sturdy and templeachingly<br />

sweet when dipped into the custard. Not for the faint<br />

hearted, but a unique dessert experience that turns a classic<br />

on its head.<br />

chai crème brûlée<br />

Serves 6<br />

Ingredients<br />

600ml thickened cream<br />

8 egg yolks<br />

¼ cup caster sugar, plus extra for sprinkling<br />

vanilla pod or 1 tablespoon vanilla extract<br />

¼ teaspoon ground cloves<br />

½ teaspoon ground cinnamon<br />

¼ teaspoon ground cardamom<br />

dash ground black pepper<br />

Method<br />

1. Heat cream, vanilla, and spices in a medium sized<br />

saucepan until on the cusp of boiling. Small bubbles may<br />

start to agitate, but do not let cream boil. Remove from<br />

heat.<br />

2. In a large mixing bowl, quickly beat egg yolks and caster<br />

sugar together, until just combined. Add half the hot<br />

cream to the egg yolks, whisking well. Add the rest of the<br />

cream and combine. Pour custard back into the saucepan,<br />

and set it over low to medium heat.<br />

3. Cook custard, stirring continuously, until it is thick<br />

enough to dollop. It should take about 10 minutes, but be<br />

patient and don’t settle for floppy custard.<br />

4. Take custard off heat and decant into serving ramekins.<br />

Place in the fridge until it is completely chilled. Custard<br />

should thicken slightly more on chilling.<br />

5. When ready to serve, sprinkle the surface of the custard<br />

with sugar. The thickness of the burnt crust depends on<br />

how much sugar you use. For a hard, toffee-like crack use<br />

approximately 1 ½ tablespoons per ramekin; for a delicate<br />

crunch use ¾ a tablespoon per ramekin.<br />

6. Blow torch sugar from a distance of approximately 5cm.<br />

You want to singe it gradually to form an even, slightly<br />

bitter crust. Serve as is or re-chill after torching. s<br />

13

payment<br />

daniel browne<br />

Robert gazed dispassionately through the rifle’s scope down<br />

at the street. The cold steel was heavy in his hands; the trigger<br />

felt hard and unyielding. Droplets of sweat ran down his lower<br />

arms as the dying rays of the sun vanished behind the horizon.<br />

Two minutes. Two minutes until the target comes into range.<br />

The target was just visible at the end of the street, moving<br />

hurriedly from car to car like a bee busily pollenating flowers.<br />

Its face was indistinguishable at this distance, but the inevitable<br />

fluoro yellow vest stood out against the twilight.<br />

Dressed to kill.<br />

Robert’s life hadn’t been easy. After his dishonourable<br />

discharge from the army, all he had to show for six loyal years<br />

of service to his country were a collection of scars on his lower<br />

thigh and a tendency to sleep for only three hours every night.<br />

And Bessie. He’d managed to save Bessie.<br />

He stroked the rifle barrel lovingly. Bessie was always there<br />

for him.<br />

The first ticket had been unexpected. He had been five<br />

minutes late returning to his car at Southbank. $82 g<strong>one</strong>. Not<br />

much m<strong>one</strong>y, perhaps, but Robert had little enough to spare.<br />

He could barely afford to renew his registration; he certainly<br />

had no m<strong>one</strong>y to throw away on parking fines.<br />

The second ticket had been justified; however, that made it<br />

no less unpleasant. $110 for the privilege of parking on a<br />

white line on a ‘private street’. Robert had paid the fine with<br />

clenched fists and gritted teeth.<br />

The final ticket was the final straw. Another $82 for parking for<br />

too long on a road with no traffic signs because of an invisible<br />

2P parking z<strong>one</strong> that stretched across the entire suburb.<br />

Robert had tried to appeal, but was casually told “you should<br />

have been more aware” by a bored council worker.<br />

You should have been more aware, he thought as the target<br />

came within range. Works just as well when the power is in my<br />

hands, not yours.<br />

Three tickets. Three tickets issued by the exact same parking<br />

officer. C1198. The number was burned into Robert’s brain.<br />

Sometimes, in the early hours of the morning, he could picture<br />

the rat-faced C1198 perfectly in his mind. A slight covering of<br />

stubble over a puffy double chin. Greasy black hair peering<br />

out from beneath a broad-brimmed hat. The aroma of old<br />

cabbage leaves and nervous sweat.<br />

Robert’s muscles tensed as Bessie’s crosshairs played over<br />

the target’s chest. Could this be the <strong>one</strong> He had been wrong<br />

before. He had only met the officer briefly, on the occasion of<br />

the first fine. There had been an argument. It had threatened<br />

to call the police. Robert couldn’t have that; it would have<br />

broken his parole. So, for the first time in his life, he had<br />

turned his back on a fight.<br />

Robert studied the target’s face intently through the scope.<br />

In his mind, all parking officers resembled rodents. This <strong>one</strong><br />

looked like a weasel with its long neck, awkward posture and<br />

beady eyes. He spotted a patch of dark hair poking out from<br />

underneath its hat. Almost without thinking, he pulled the<br />

trigger.<br />

Gotcha.<br />

The sound of the rifle shot reverberated down the empty<br />

street. Robert jumped down the steep embankment then<br />

sprinted across to the collapsed target. He did not think about<br />

the pathetic sobs. He did not think about the way the target<br />

clutched at its throat as it tried to stop its lifeblood flowing<br />

into the gutter. His mind was focused on only <strong>one</strong> thing:<br />

The officer’s identity number.<br />

Robert rummaged inside the yellow jacket. He ignored the<br />

choking gasps and the blood-soaked hand clawing at his thigh.<br />

Robert grunted as he flipped open the slim, black wallet.<br />

C1140.<br />

“Fuck.” His feeling of disappointment was tangible. Wrong<br />

yet again.<br />

That’s the fifth <strong>one</strong> today. I have to get going if I’m going to<br />

find C1198. Once the police find these bastards, it’s game over.<br />

Robert hesitated. He looked down into the desperate, dying<br />

eyes near his feet.<br />

“You got in my way, mate. Nothing personal. You should<br />

have been more aware.” s<br />

14

four seasons<br />

sam banks<br />

A streak of white cuts through the empty blue sky, like<br />

some<strong>one</strong> scratching a key along a brand-new car. The vibrant<br />

shade of blue reminds me of something I’d seen in a magazine,<br />

a resort at a place called Bora Bora. Little touristy huts built on<br />

stilts, peppering the cobalt water, all connected with curving<br />

boardwalks. I’m not too sure where Bora Bora is, but I’ll have<br />

to get Richard to buy tickets there when he decides to retire.<br />

If he ever decides to retire. I can hear classical music playing<br />

from a distant source, <strong>one</strong> of those tracks that every<strong>one</strong> seems<br />

to know. I drift in and out of the peaceful sounds of suburbia,<br />

my eyelids feeling heavy and my thoughts sluggish, as if I’d<br />

awoken from a coma.<br />

I roll my head to the side. I realise I am lying on the concrete<br />

tiles of our patio. On my left is our immaculately maintained<br />

backyard with the pool we never swim in, bordered with<br />

sculpted hedges. On the other side is the house. It’s two<br />

storeys, air-conditi<strong>one</strong>d, and well furnished. A safe, white<br />

neighbourhood. From where I’m lying, I can see the kitchen<br />

and the living room through our large glass doors. Art that we<br />

pretend to appreciate lines the walls, and Vivaldi is drifting<br />

through the panes from our expensive stereo system. I must<br />

have left it on.<br />

A muted ache is creeping up the back of my brain, making<br />

it hard to remain in the sedated peace of my daydreaming.<br />

I have this awfully persistent feeling that I forgot something<br />

important. Like when you go on holidays and you suddenly<br />

think you left the stove on, so you force your husband to drive<br />

the four hours back from Pittsburgh to confirm that, yes dear,<br />

the stove is off. That kind of feeling. Had I left the stove on<br />

No, today was Thursday. I was going to do some chores in<br />

the morning, then meet Cathy for lunch. (Her husband just<br />

left her. Serves the bitch right.) Then, I have my homeowners<br />

association meeting until the evening. I have to clean the<br />

gutters, trim the rose bushes. No, I’ve already cleaned the<br />

gutters. The realisation doesn’t shock me. It just comes to me,<br />

like the answer to a trivia question.<br />

Spring rain had been falling inconsistently for the past week<br />

now, and our roof was covered in leaves and twigs from the<br />

neighbour’s irritatingly overgrown oak. I would have forced<br />

Richard to go up there, but he always gets home so late, and<br />

it was the Mexican’s day off. I’d been shovelling detritus from<br />

the gutters all morning, so I’d decided to look over into the<br />

Warner’s residence, in case there was another juicy morsel of<br />

gossip braising in their dysfunctional home. But I had leant too<br />

far, hadn’t I Then that sickening sense of falling backwards,<br />

my arms clutching at air as the roof drifted away from me. I<br />

hadn’t felt that feeling since going to amusement parks as a<br />

15

kid. It’s something I’ve g<strong>one</strong> out of my way to avoid since. I<br />

will myself to move, but nothing happens. Something is very<br />

wrong. I look down at my arms, coercing them into shifting,<br />

silently begging them to budge with my stare. Come on now.<br />

My limbs lie still, twisted in the positions they fell in, like a<br />

puppet with its strings cut. I can feel beads of sweat running<br />

down my forehead, stinging as they get in my eyes. I start to<br />

breathe more heavily.<br />

“Rich!” I call.<br />

Of course. He’s at work.<br />

“Help! Somebody help me!”<br />

The neighbourhood remains silent but for the distant roar of<br />

a mower and the thin violins coming from inside. Threatening<br />

grey clouds have begun edging into my peripheral vision.<br />

It’s fine. It’s all going to be perfectly fine. I’ll just wait for Rich<br />

to get home. It’ll be humiliating and graceless as hell, but he’ll<br />

scoop me up with those spindly arms of his and take me to the<br />

hospital. The doctor will consult his charts and, with a dramatic<br />

pause, say “congratulations, you’re not a quadriplegic,” and<br />

I’ll be discharged in time to get to my meeting to stop Martha<br />

from getting that eyesore of a fence. I just hope to God n<strong>one</strong><br />

of those catty whores see me being carried to the car.<br />

That wouldn’t even be the worst of it. Daisy fucking Peterson,<br />

the cripple from the homeowners association, would be the<br />

worst of it. At least she broke her back elegantly. T-b<strong>one</strong>d in<br />

an intersection, if I remember correctly. I’ve always thought<br />

there’d be nothing wrong with dying in a car crash. Princess<br />

Diana had it right. Sophisticated, sudden, and deliciously<br />

tragic. Not falling off the roof while cleaning the fucking<br />

gutters. I can see it now. Daisy would sinisterly roll up, with<br />

a look of sadistic schadenfreude in her eyes. And she’d say<br />

something like “Don’t worry dearie, it gets easier.” Like I’m<br />

somehow on the same level as her.<br />

He won’t leave me. Richard I mean. Not because there is any<br />

semblance of intimacy or affection between us anymore, but<br />

he’s just too much of a goddamn pussy. It’s an election year,<br />

after all. If there’s <strong>one</strong> thing voters hate it’s guys who abandon<br />

their wives after they fall off roofs and break their necks. No,<br />

Richard would play the dutiful husband and wheel me out to<br />

press shoots, and I’d say something like “I wouldn’t be here if<br />

it wasn’t for him. He’s my rock” as the flashbulbs burst around<br />

us. Hell, he should be thanking me.<br />

The mower stops. I take this as an opportunity to tear my vocal<br />

cords apart with an earsplitting “GODDAMN FUCK SOMEONE<br />

HELP ME!” My voice cracks and falters towards the end.<br />

The dull ache is leaking through my neur<strong>one</strong>s, sending electric<br />

daggers stabbing into my brain. The clouds are gathering, fuller<br />

and blacker. Typical. As soon as I do some cleaning, nature<br />

decides to fuck with me again. First gravity, now precipitation.<br />

I was acutely aware of the futility of yard work. No matter how<br />

much I try to stave off nature’s incessant march, it’s all just<br />

putting off the inevitable. Fuck it. I’m dying in a car crash, not<br />

like this. With herculean effort I rotate my body onto its side.<br />

Unspeakable, incomprehensible agony. B<strong>one</strong> and cartilage<br />

grate against each other, sending sparks of pain bouncing off<br />

my spine. I reach my hand towards the door, feeling like it<br />

was being torn out of my body. I hear a car pulling into the<br />

driveway.<br />

My initial optimism is tempered with confusion. Richard is at<br />

work right now. I wait, craning my neck to see who will enter<br />

the living room. Suddenly my husband and a woman tumble<br />

into my frame of vision, too busy shedding clothes to pay any<br />

attention to the heap lying outside. I recognise her from the<br />

campaign office. Young and bright, she would be going places<br />

once she finished coming. They reach the kitchen, with Richard<br />

concentrating on disassembling the woman’s bra, trying not to<br />

be too distracted by her tongue running along his clavicle. He<br />

ends up crudely tearing the flimsy thing off and propping the<br />

girl on the table, facing away from him.<br />

She knocks over a wine glass I had been sipping from. It<br />

hits the floor and shatters, the red liquid spilling across the<br />

linoleum and seeping into the carpet. They pay no attention.<br />

He’s fucking her like some<strong>one</strong> hammering a tent peg into the<br />

ground.<br />

He looks over at the window, perhaps hoping to catch a<br />

reflection of himself. The spiralling strings joyously herald his<br />

imminent climax. His ecstasy-full eyes slowly travel through<br />

the glass and widen. He stops mid-thrust, mouth agape and<br />

blinking as he tries to process what’s in front of him. The girl<br />

feels him stop and looks over in parallel, both frozen and<br />

naked in their positions on my once-sanitary kitchen counter.<br />

It starts to rain.<br />

He sees me, crumpled and ruined in a heap on the concrete,<br />

my limbs twisted and my head arching towards him. I give him<br />

a devilish grin.<br />

I’m going to destroy you. You’re going to wipe the shit off my<br />

arse for the rest of your life, you bastard. Good luck bringing<br />

your sluts upstairs into our bedroom when my chair lift gets<br />

jammed halfway up. She can change my colostomy bag while<br />

you fumble for your condoms. You’re damn well going to take<br />

me to Bora Bora, and you’re going to sit by the blue water<br />

with me as we grow old and miserable together. s<br />

16

albion flour mill<br />

words and photographs: matthew wengert<br />

In late November 2013, Brisbane<br />

lost a significant remnant of<br />

its architectural heritage: the<br />

Defiance Flour Mill at Albion.<br />

The brick factory was destroyed<br />

in a deliberately lit fire, and<br />

demolition of the ruins began the<br />

following day. This impressive<br />

Depression-era building, which<br />

had stood on the site for over<br />

eighty years, was g<strong>one</strong> in just two<br />

days.<br />

17

efore the fire<br />

18

esperanza<br />

jane etherton<br />

On Saturday the 7th and Sunday 8th of December 2013, the<br />

Greenpeace ship Esperanza was docked in Brisbane on its<br />

way to survey the Great Barrier Reef. While here, the crew<br />

opened the ship to the public to show them what life is like on<br />

board and to explain the important work that they do. On the<br />

Saturday I had the opportunity to take part in this experience.<br />

From the first moment I arrived at the docks people were keen<br />

to talk and help us out with any information or questions that<br />

we had. All volunteers, this was a very friendly team.<br />

The crew of the ship are mostly volunteers, as with all<br />

Greenpeace ships, and were happy to show us around and<br />

share the stories of how they came to be working on the ship.<br />

Launched in February 2002, the Esperanza is the largest and<br />

most recent addition to the Greenpeace fleet. The Esperanza<br />

– Spanish for ‘hope’ – is the first Greenpeace ship to be named<br />

by visitors to the Greenpeace website.<br />

Originally commissi<strong>one</strong>d by the Russian government for heavy<br />

ice class and speed, the Esperanza is <strong>one</strong> of 14 ships built<br />

in Stocznia Polnocna construction yard in Gdansk, Poland,<br />

between 1983 and 1987. The Esperanza was intended to be<br />

used by the Russian Navy as a fire-fighting ship in Murmansk.<br />

At 72 metres, and with a top speed of 16 knots, the ship is<br />

ideal for fast and long-range work. In relation to the work<br />

the Esperanza does for Greenpeace the ship’s ice class status<br />

means it can work in Polar Regions, as well as more tropical<br />

areas.<br />

The Esperanza is a working ship, and because of this, as visitors<br />

we were only allowed into a few select areas, supervised by a<br />

guide. In each of these areas we met a crewmember who told<br />

us about their role on board and some of the work that the<br />

Esperanza has d<strong>one</strong> in the past. Our guide Miriam first took<br />

us to the lower deck (poop deck) where we were told about<br />

the history of the Esperanza and had our questions answered<br />

about Greenpeace and the history of Greenpeace ships—the<br />

best known, of course, being the Rainbow Warrior (the current<br />

Warrior is the third in succession)—and the development of<br />

the work that the ships and their crews do.<br />

Next we went upstairs where we met Jane, and were shown<br />

a short video about the current Greenpeace campaign to save<br />

the Great Barrier Reef from dredging and drilling, the current<br />

campaign for the Esperanza. Lastly we went up another level,<br />

past life rafts and buoys to the main control cabin and met<br />

the third mate, who told us about the controls and how to get<br />

involved working or volunteering on a Greenpeace ship.<br />

It was a fun and informative day out and I recommend taking<br />

an opportunity like this next time <strong>one</strong> of these ships is in the<br />

area, particularly if you have an interest in environmental<br />

campaigns or ship work. This may be a great way to get to<br />

work on <strong>one</strong> of these ships and see the world while helping<br />

to protect it.<br />

If you would like more information or to volunteer with<br />

Greenpeace, you can look up the campaigns and local offices<br />

on the Greenpeace website. s<br />

19

some things you should know<br />

cindy keong<br />

Dad hasn’t parted with the old washing<br />

machine. He proudly claims it’s the first<br />

automatic. There’s nothing automatic about it now.<br />

So unless you’re packing enough clothes for the entire trip<br />

the gumboots and broom handle beside the tub<br />

must be used to avoid electrocution.<br />

Make sure you visit the Bobby Dazzler<br />

there’s a 20ft statue of a fossicker crouching out front.<br />

It’s worth the five dollars just to wander the underground<br />

tunnels and escape the blistering heat. I hope you like early<br />

mornings. The bottlebrush is in bloom and the lorikeets flock in<br />

around 5 am for their all day bender. If this doesn’t wake you, Dad will.<br />

Do you remember when we were kids<br />

From our beds we would listen<br />

to the blueprint of morning<br />

heavy footsteps making a cup<br />

of tea, the scuff of brush and polish<br />

on boot leather, the heady waft of his first cigarette.<br />

It’s still the same, still in order.<br />

20

jesus<br />

cindy keong<br />

You would argue that until you were seven<br />

you thought your name was Jesus. <br />

That Dad picked over your transgressions<br />

like a crow pecks at roadkill. Every false move<br />

recorded in sighs of, Oh Jesus!<br />

Trouble attached itself to you<br />

like a cattle tick. At six, other boys <br />

were climbing trees, learning how to ride<br />

bikes without training wheels. <br />

You were smoking cigarettes<br />

inventing excuses for singed fingers<br />

and the absence of eyebrows, the truth<br />

buried deep in blue denim pockets.<br />

Your boyish smirk still appears when we<br />

trade memories like baseball cards: <br />

you recall convincing Mum that crayfish<br />

caught in our local creek were called cunts.<br />

The delight savoured not in the tasting<br />

but in Mum’s proud exaltation when served<br />

at the dining room table.<br />

These days Dad watches you play<br />

with your son, raising him high<br />

on outstretched arms, catching him as he free-falls.<br />

Dad no longer calls you Jesus, but comments on<br />

how your son looks at you like a God. s<br />

21

the sum of your things<br />

alyssa miskin<br />

I am a childhood trinket<br />

from an aunt you never liked<br />

fallen over in the back of a cupboard<br />

the backup pair of ballet shoes<br />

your mother bought<br />

even though you never wore the first<br />

I am the biography<br />

on your bedside table<br />

always almost halfway read<br />

Your grandmother’s tea set<br />

in the glass cabinet<br />

too precious, too pretty<br />

to use<br />

I am the photo on the wall<br />

down too close to the floor<br />

and your expectant jewellery box<br />

waiting for expensive gifts<br />

I am not your favourite cousin<br />

the <strong>one</strong> who smells of jasmine<br />

Not your oldest and ugliest stuffed toy<br />

that you keep to show your kids <strong>one</strong> day<br />

I am not even a quiet child<br />

forgotten at the shops<br />

remembered halfway to the car<br />

reminded by a wallet photograph<br />

I am just a used and out-of-style jacket<br />

discarded on the bus<br />

when the weather got warm s<br />

22

dark musings<br />

james wright<br />

Part 1<br />

12 June 2027<br />

Alena walked slowly across the polished wooden floors, leaving<br />

a trail of bloody footprints. Less than halfway across, she leant<br />

heavily against the back of her reading chair, gripping its high<br />

back with <strong>one</strong> hand and pressing the other to her side in an<br />

effort to ease the pain. The grandfather clock loudly sounded<br />

a quarter to the hour, almost as loud as the beating of her<br />

heart, before subsiding into the soft regularity of its tick-tock.<br />

The two rhythmic sounds, clock and heart, merged together<br />

in her head, marking the passing of the seconds. Not for long.<br />

She swallowed and offered a small prayer to whatever gods<br />

were listening. Please let it be long enough.<br />

Mustering her strength, she pushed away from the chair,<br />

ignoring the red smears against the snowy leather. It wasn’t<br />

her problem at the moment. Wouldn’t be her problem ever<br />

again. Oh, Isaac. Painfully, she shoved the thought away.<br />

Concentrate! Resuming her unsteady stagger, Alena kept her<br />

eyes focussed on the well-worn leather cover of her journal<br />

resting on her desk. A few more metres.<br />

A log within the fireplace popped loudly, breaking her<br />

attention. She twisted sharply towards the sound, collapsing<br />

heavily as her right leg buckled in a new wave of pain. Looking<br />

down, she saw just how bad the wound was. It would be the<br />

death of her, if the equally cruel wound in her side didn’t kill<br />

her first. A wry laugh bubbled from her lips, followed by a<br />

wracking cough. The thrusts of pain flared as the cough<br />

spasmed through her tiny frame, consuming her world.<br />

The clock tolled the hour jolting her back to consciousness.<br />

Awareness of her situation crystallised; Alena realised she had<br />

but moments left before all would be und<strong>one</strong>.<br />

She went to stand, but slipped in the pool of blood that had<br />

spread around her in the minutes she had lay there. There<br />

was a chill in her limbs, an emptiness seeping into her mind.<br />

Angrily, she pushed it away. Stretching out, Alena dug her<br />

fingernails into the floor, seeking purchase to pull herself<br />

forward. It took time. Too much! Yet, minutes later, she was<br />

able to force herself into a kneeling position at the base of her<br />

desk.<br />

Fumbling hands scrambled across the cluttered surface<br />

searching out her journal. A rain of papers and books fell over<br />

her but she was beyond caring. After an eternity, the journal<br />

fell to the floor beside her. A satisfied, bloody smile flashed on<br />

momentarily, extinguished by the thought that the task was<br />

still incomplete.<br />

Gripping the journal in the blood-crusted fingers of <strong>one</strong> hand,<br />

Alena stretched herself out towards the crackling fire. The<br />

seconds ticked by as she eased herself across the floor. Not<br />

that it was easy. Easy would be giving up. Easy would be letting<br />

it all go. She set her mouth into a determined line, focussing<br />

on reaching the fire. Easy wasn’t an option. Not yet.<br />

Outside, she heard the throaty growl of Isaac’s motorbike. His<br />

other love. A jolt of panic surged through her, and, using its<br />

drive, Alena groped the remaining distance to the fierce heat<br />

of the fire. Downstairs, Isaac would be fumbling for his keys<br />

with gloved hands, cursing the winter cold and cursing not<br />

having had the garage door motor fixed. A cold of a different<br />

kind crept over Alena, competing with the warmth of the blaze<br />

before her.<br />

Thrusting the journal into the bricked alcove, Alena let the<br />

cold in, even as the heat soothed her. She rolled on her side,<br />

allowing herself to give in. Her eyes drifted around the study,<br />

floating above the details. Trails of blood over the polished<br />

floorboards. The scattered papers from her scrambling at the<br />

desk. The corpse of her life-long friend spread out on the<br />

couch. Nothing mattered, now. It was d<strong>one</strong>. I’m sorry, my<br />

love. I’m sorry. Whether the thought went to her husband,<br />

Isaac, or to the corpse, even Alena didn’t know.<br />

And then, she was g<strong>one</strong>. s<br />

23

dust bunnies<br />

caitlin morgan<br />

Ellen came to see me today. She brought raspberry friands that<br />

made my throat itch. I can tell how relieved she is to be able<br />

to look in from the outside. When we broke up she helped me<br />

move back into my childhood bedroom and then never called<br />

me again. She sent a card when she heard Mum was sick, but<br />

only out of misplaced guilt. They didn’t get on. I told her that<br />

she shouldn’t care, but it used to really eat her up.<br />

I haven’t been into Mum’s room since she died. Her door’s<br />

been shut, so I imagine that the air in there still holds her scent<br />

and her exhaled breaths. I’m pretending she’s still inside, that<br />

she’s had a big night and will be grumpy if I wake her.<br />

pack of Sobranie Cocktails in her desk drawer. I pick <strong>one</strong> in<br />

lilac from the spectrum of putrid pastels and wedge it between<br />

my lips. Also in the drawer is a little brown and gold photo<br />

album that I’ve never seen before.<br />

I look at Mum through time; as a baby, a schoolgirl, her first<br />

communion. Then as a debutante, graduate, bridesmaid at a<br />

wedding. Then there’s a family portrait. Mum with a man who<br />

has toddler Meg on his hip, smiling at Mum who has baby me<br />

in her arms. Meg’s first birthday, there he is again. My birth,<br />

our christening. Feeding ducks with Meg. The same man,<br />

riding behind me on a fat Shetland pony.<br />

She didn’t die in there, she died in the hospital: clammy,<br />

frail, and covered in tubes. Attached to machines that beeped<br />

and hissed and breathed for her. Her wild hair cut short. The<br />

vibrant red henna faded to carroty orange and grown out with<br />

long silver roots.<br />

My sister is coming to stay and she’ll need somewhere to sleep.<br />

Her old room is full of junk from Mum’s theatre: broken set<br />

pieces, mouldering costumes, shrunken commedia dell’arte<br />

masks. Meg will want to sort through all of Mum’s things when<br />

she gets here. I want to touch them first.<br />

I’m in. The prevailing scent is mildew. I should open the<br />

windows and let some air circulate, but it’s still raining.<br />

Some<strong>one</strong> else has been in here. Mum’s crystal ashtray is<br />

empty. All of her scripts have been stacked into a neat pile,<br />

and there aren’t any wine glasses or coffee-stained cups.<br />

Everything looks straightened and smoothed out. There is a<br />

24<br />

I’ve ashed on the bed. The little grey clumps burst in my<br />

fingertips and leave a sooty stain on Mum’s paisley bedspread.<br />

My eyes blur and the pattern writhes like cartoon amoebae in<br />

a high school science video.<br />

Mum had always been so cagey about our father. As we got<br />

older she sketched an increasingly vague portrait of him. He<br />

was an actor. No, a director. They had a turbulent affair during<br />

The New Wave, when every<strong>one</strong> was drunk all the time. He<br />

killed himself. Died of a heroin overdose. No, he was gay. He<br />

left her for another woman when Meg was three, and I was<br />

still in the womb. He was married and went back to his wife.<br />

I stopped asking about him when I was quite young, but Meg<br />

used to push her. I see it now. My weak chin and sad eyes.<br />

Meg’s blockish figure. Alan. Shy Alan, who cleaned Mum’s<br />

theatre.<br />

When we’d go there after school, Meg would do her<br />

homeworkand Alan would give me jobs. I’d crawl through<br />

the rows of seats groping in the darkness for fallen coins, lost

car keys or the occasional earring. More often than not, I’d<br />

find aband<strong>one</strong>d programs, chocolate wrappers, and clumps of<br />

dust. I found a Zippo once, and Alan had let me keep it. Wateryeyed<br />

Alan. Married to Maureen who made the costumes.<br />

The gate squeals and Meg is stomping up the front stairs.<br />

Without a word she dumps her bags, kisses my forehead, and<br />

makes for the electric kettle. It roars and bubbles and steams<br />

and then switches off with a loud click. She sets down a big<br />

mug of tea in front of me. The stegosaurus mug.<br />

“I found an agent, so the house is listed now,” says Meg.<br />

“They’ll come around and put up a sign tomorrow.”<br />

“Great.”<br />

I look out the window and picture a real estate sign with<br />

some grinning jerk on it sinking into the mud. Soon we’ll<br />

have to contend with strangers tracking wet grass through the<br />

house. They’ll look in all of the rooms and think about where<br />

they’ll put their own furniture while their wet umbrellas leave<br />

puddles in the hall.<br />

Meg’s eyes drift around the room, taking in all of the poster<br />

versions of Mum. Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, Streetcar<br />

Named Desire, The Cherry Orchard, The Removalists, Don’s<br />

Party, Mother Courage, The Glass Menagerie, Hamlet,<br />

Dimboola, The Crucible, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Oedipus Rex,<br />

The Tempest. We sat through them all. Meg looks down at my<br />

fingers.<br />

“Why are you wearing her rings Who are you, Norman<br />

Bates”<br />

“I found them in a drawer, calm down.”<br />

“This is too weird, Doug. Christ! She’s smothering you<br />

from beyond the grave.”<br />

Part of me wants to stay here forever, swaddled in her<br />

possessions. The house is going to take a lot of work, and<br />

the garden is dead. What didn’t get scorched in the heatwave<br />

drowned in the ensuing flood. Mum’s hedge of tea roses didn’t<br />

survive. Their lifeless, thorny branches jut out of the sodden<br />

earth at odd angles. Unchallenged, the aloe vera has taken<br />

over the back garden like a giant spiny monster. It’s spilling<br />

out of the garden bed and slowly making its way across the<br />

lawn.<br />

We’re packing away Mum’s life. What doesn’t go to Lifeline will<br />

be left out on the lawn for the vultures.<br />

“I’ll get that.”<br />

Meg dashes to catch the ph<strong>one</strong> before it rings out. She can’t<br />

wait to sell the house.<br />

“Maureen wants to come over. She says that she has a few<br />

things of Mum’s. A punch bowl and a fondue set or something.<br />

Do you want those” Meg calls from the other room.<br />

“Alan is our Dad,” I whisper to my reflection in the<br />

microwave door.<br />

The idea still doesn’t sit right with me. He’s hardly the<br />

impassi<strong>one</strong>d lothario she had us imagine.<br />

“Of course, they’ll probably just end up in the pile for<br />

Lifeline. I’ll call back and tell her not to worry.”<br />

“She can keep them. I can’t even cook a frozen pizza; what<br />

would I do with a fondue set Don’t you want it You could use<br />

it as a foot spa.”<br />

Meg doesn’t want to keep anything. She’d happily build<br />

a bonfire. Mum’s sagging cane furniture and Indian rugs<br />

wouldn’t fit into her lacquered wood and raw st<strong>one</strong> Bang &<br />

Olufsen aesthetic.<br />

“Maureen. Remember how she used to trap us in those<br />

big woolly cuddles” Meg gasps for breath and itches her face,<br />

shuddering at the memory. I do remember.<br />

“Her breasts were terrifying.”<br />

Meg finds a crown that Mum wore when she dressed up as<br />

Glinda for <strong>one</strong> of Meg’s birthday parties. She smooths down<br />

her hair and puts it on.<br />

“Maybe I will keep this,” she says.<br />

I’ll keep the album and the stegosaurus mug, but everything<br />

else can go.<br />

By some miracle, the sun is out. The ground is still wet, but<br />

we’ll put tarps down. Today we’ll put all of her possessions<br />

out on the front lawn. They’ll come, and piece by piece they’ll<br />

take her away. s<br />

25

grandad’s greenhouse<br />

alyssa miskin<br />

Think of the most gorgeous smelling perfume you can buy,<br />

and then double the power of that scent. You have almost<br />

come close to the perfume of my Grandad’s orchids. I was<br />

about ten the first time I was allowed to touch something<br />

in Grandad’s greenhouse. I’d been allowed to walk inside it<br />

supervised for a few years, but I had to act like it was a china<br />

display; the orchid petals would fall off if I so much as inhaled<br />

near them.<br />

Dad, Grandad, and I were in the greenhouse, parts of which<br />

were older than me by about forty years, sorting out which of<br />

Grandad’s potted plants would move to the new house. I’m<br />

not sure what kind of system of organisation we were using,<br />

or what the final plan involved, all I knew was we were moving<br />

hundreds of black plastic pots and their precious flowers from<br />

<strong>one</strong> side of the greenhouse to the other.<br />

I was at the doorway end so I could quickly escape from the<br />

greenhouse air—it was hot and thick with the chemical-burn<br />

smell of fertiliser and compost mulch. I had to duck under<br />

hanging plants and falling greenhouse mesh as Dad and<br />

Grandad dismantled the frame at the other end. Decades<br />

of lost and half-melted toys, frisbees, and soccer balls were<br />

thrown at me as Dad and Grandad uncovered them from<br />

among the pots and polystyrene compost, or fell from their<br />

long-time captivity in the roof.<br />

“Here, Leesa… Liza… Ah, uh, Alyssa-Kate.”<br />

I could never tell if he actually didn’t remember my name, or<br />

if he was joking. He was holding out a spanner on the flat of<br />

his palm.<br />

“Take this,” he wheezed. That was the first time I noticed<br />

he ran out of breath quickly. It was what got him in the end.<br />

I stepped deeper into the mottled greenhouse and looked up<br />

at Grandad smiling crookedly under his floppy beige hat. I<br />

lifted the spanner off his hand and he let rip a massive, rippling,<br />

guttural fart. Think of the most horrible smelling rubbish bin<br />

you can find, and then double the power of that scent. You<br />

have almost come close to the perfume of my Grandad’s fart.<br />

“Nice <strong>one</strong>, Pop,” Dad called out.<br />

I was not, strangely, impressed when the odour from Grandad’s<br />

pants pervaded my nostrils; I missed the smell of fertiliser,<br />

compost, and mulch. And any time I smell orchids now, their<br />

sweet perfume has a sinister undert<strong>one</strong> that reminds me of<br />

Grandad’s heavy, spicy, decomposition-scented fart. s<br />

26

lactocracy<br />

daniel browne<br />

Contemporary Australia is a dark and uncertain place.<br />

Democracy has failed us. Children cry in the streets.<br />

Revolutionaries sharpen their axes as they prepare for<br />

inevitable civil war. The very foundations of our government<br />

are unravelling as people clamour for change.<br />

The evils that currently beset our society have their origination<br />

in two words. Two shameful words that should never be<br />

uttered in polite company. Two despicable words that are<br />

dirtier than the most graphic expletives.<br />

Yes, dear friends. I am speaking about lactose intolerance.<br />

By lactose intolerance, I am not referring to people who suffer<br />

from a medical condition that make them unable to digest<br />

lactose. I am referring to the unmitigated and irrational hatred<br />

of dairy products. I am referring to the gangs of thugs that<br />

roam our streets smashing milk bottles, pouring yoghurt into<br />

the gutters and raiding cheese shops. I am referring to the<br />

recent spate of hate posters with slogans like Got Milk No.<br />

I am referring to the gangland-style execution of innocent<br />

cattle.<br />

How can a civilised society cond<strong>one</strong> this behaviour Dairy<br />

products are essential for our physical, mental and spiritual<br />

health. In Norse mythology, Ymir—the ancestor of every living<br />

creature—was suckled on the milk of the great cosmic cow<br />

Auðumbla. To this day, Hindus and Zoroastrians revere the<br />

cow as a sacred animal. And what were the fleeing Israelites<br />

promised in the Bible A land of milk and h<strong>one</strong>y.<br />

Dairy products are everywhere, and everywhere they are<br />

a force for good. Do we not live in the Milky Way galaxy A<br />

school of thought exists that suggests the moon may indeed<br />

be made from cheese. In our formative years we are sustained<br />

by mother’s milk, and milk helps us grow throughout our<br />

lives. For once, science and religion are in agreement—dairy<br />

productsare essential to human society.<br />

We should all aspire to be like Shane Fuller, a heroic Brisbane<br />

milkman who doused a dangerous fire in Spring Hill in 2013<br />

using bottles of milk. In his own words: “The flames were<br />

about half-a-metre high—some of the mulch and palms were<br />

starting to burn. I didn’t have any water so I just grabbed some<br />

bottles of milk and just drenched it.”<br />

Once again, milk conquers evil. If only intolerance could be<br />

conquered so easily. The time has come, dear friends. Throw<br />

away the shackles of democracy and embrace lactocracy. Rivers<br />

will run with pure white milk. Glorious mountains of Gouda<br />

will be reflected in delicious lakes of cream. Puffy clouds of icecream<br />

will rain down droplets of butter across perfect fields of<br />